Main Contents & Search

.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

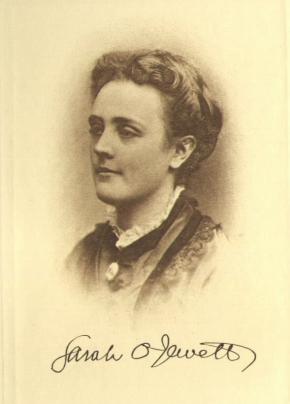

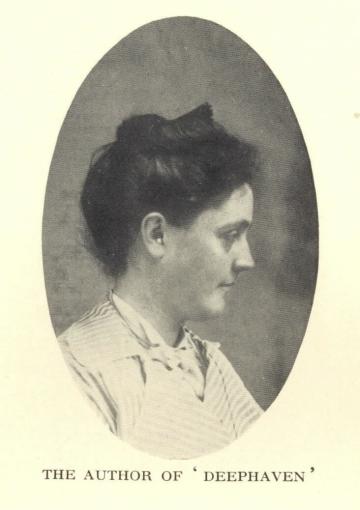

SARAH ORNE JEWETT

by

Francis Otto Matthiessen

With Illustrations

Boston and New York

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

Copyright, 1929, by Francis Otto Matthiessen

TO

THE MEMORY OF

MY MOTHER

LUCY ORNE MATTHIESSEN

Edited for Internet publication by Terry Heller, Coe College.

Editor's Note

Willa Cather, for one, found this biography less than satisfactory. In a 22 November, 1934 letter to Edward Wagenknecht, she wrote:

What an inadequate book that young man did write about Miss Jewett! He misinterprets so many of the facts that he dug up, and she herself never for a moment graces his pages. It seems to me that even if I had never known her, I could have reconstructed her from her letters to Mrs. Fields and her published works. This young man is modern and abrupt. Before he wrote his book he sent me a letter which said simply: "At what date can I call upon you for information regarding Sarah Orne Jewett?" I think I told him January 1,1990.... (The one good thing about that young man's book is that it contains some very charming drawings and photographs of that beautiful New England interior.) It is a disgrace to New England that any of Miss Jewett's books should be out of print. It will be a long while before New England produces such another writer. (The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, 2013, by Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout, pp. 111-3).

SARAH ORNE JEWETT

(1849-1909)

I

Contents

THE first thing she could remember was a world bounded by the white paling fences around her house. There were wide green yards and tall elms to shade them. There was a long line of barns and sheds, one of which had a large room upstairs with an old ship's foresail spread over the floor and made a wonderful play-room in wet weather. Apples were laid out to dry there in the fall, and there were some old chests and discarded pieces of furniture to keep house with. She used to climb up on the fence next the street, and watch the people go in and out of the village shops that stood in a row on the other side, with their funny-looking upper stories bulging out over the sidewalk, and the bright red chimneys clustered together on their pointed roofs.

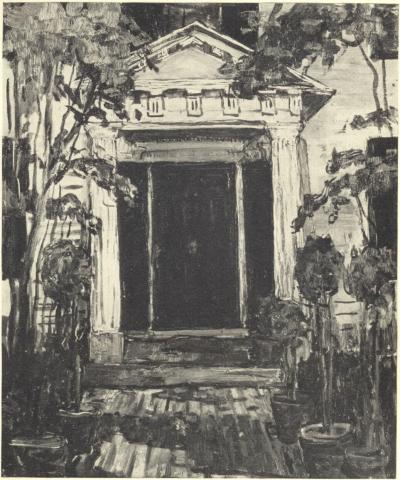

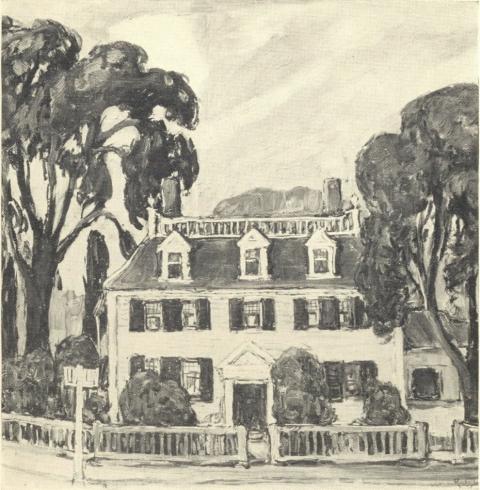

Front Door of the Jewett House at South Berwick

From a painting by Russell Cheney

But the front yard she knew best belonged to her grandfather's house next door. Sarah was happiest when she could smuggle herself into that front yard with its four lilac bushes, and the brick walk leading down to the latched gate. It was like a miracle in the spring when the yellow and white daffodils came into bloom. And later came the larkspur and the honeysuckle, Canterbury bells and London pride. A good many ladies'-delights always grew under the bushes and sprang up anywhere in the chinks of the walk or the doorstep, and a little green sprig called ambrosia was a famous stray-away. Outside the fence one was not unlikely to see a company of French pinks, which were forbidden standing room inside as if they had been tiresome poor relations. Sarah could remember the time when she couldn't look over the heads of the tiger lilies, and when she had to stand on tiptoe to pick the crumpled petals of the cinnamon roses to make herself a delicious coddle with cinnamon and damp brown sugar.

Her grandmother was a proud and solemn woman, who hated Sarah's mischief and rightly thought her elder sister a much better child. She had a prized tea-rose bush, and what should Sarah find one morning but a bud on it: it was opened just enough to give a hint of its color. Sarah was very pleased. She snapped it off at once, for she had heard so many times that it was hard to make roses bloom, and ran in through the hall and up the stairs, where she met her grandmother on the square landing. She sat down in the window-seat, and Sarah showed her proudly what was crumpled in her tight warm fist. She could see it -- it had no stem at all -- and her grandmother's face for many years.

Sarah was afraid of her grandmother when she was in the house, but shook off even her authority, and forgot she was under anybody's rule when she was out of doors. She said afterwards that she had been first cousin to a caterpillar, if they called her to come in, and own sister to a giddy-minded bobolink when she ran away across the fields, which she did very often. It was not until later that she grew to love the house itself. It had been built in the days of the Revolution, and behind its brass knocker and solid, panelled door opened a deep hallway, out of the rear lights of which one caught a glimpse of flagstones and a horse block for the carriage entrance, through a posted gateway into the great garden with its pear and apple trees, and a long row of Lombardy poplars beyond. It was said that it had taken three men a hundred days to do the wood carving of that hall and its wide arch and easy stairway which led past the broad landing and pulpit window to the floor above. The block paper on its walls had been brought over from England, as had many of the spindle-legged or claw-footed chairs in the eight square rooms that gave on it above and below, the stately mahogany in the library and parlor on either side, the Adam mirrors and Chinese vases, the willow pattern and Lowestoft in the breakfast room. In an ell to the rear was the kitchen, a comfortable line of kettles and ladles glinting in front of the enormous fireplace. In one of the four-posted beds upstairs Sarah Jewett had been born, and although she spent the first years of her childhood in the house next door, she was always to think of this as home.

The night her grandmother died remained fresh in her mind. All the family were at the great house, and she could see that lights were carried hurriedly from one room to another. A servant came to fetch her, but she would not go. Her grandmother was dying, whatever that might be, and she was taking leave of every one -- she was ceremonious even then. Sarah did not dare go with the rest. She was afraid to be with the dying woman, and she was afraid to stay at home alone. She was only five years old. It was December, and the sky seemed to grow darker and darker. She went out at last to sit on a doorsill, and began to cry softly to herself. She heard some steps, and the front bell rattled loudly, but she did not move. When her mother finally came back, her face pale and tear-stained, she found her there cold and in terror .... But as for the funeral, it gave Sarah vast entertainment; it was the first grand public occasion in which she had taken any share.

Her world soon expanded to include the village. She kept no more cherished memories than the times she had gone to call on Miss Cushing, an elderly friend of her mother's who lived in a most pleasant and stately fashion. Sarah used to put on her very best manner, and had no doubt that her thoughts were very well ordered, and her conversation as proper as she knew how to make it. She could remember that she used to sit on a tall ottoman, with nothing to lean against, and her feet were off soundings, she was so high above the floor. They discussed the weather, and Sarah said that she went to school (sometimes) or that it was now vacation, as the case might be, and they tried to make themselves agreeable to each other. Presently the lady would take her keys out of her pocket, and sometimes a maid would come to serve them, or else the lady herself would bring Sarah a silver tray with some pound-cakes baked in hearts and rounds, and a small glass of wine. Sarah proudly felt that she was a guest, and a thrill of satisfaction went over her for her consequence and importance. A whole handful of sugarplums would have seemed nothing beside this entertainment. She was careful not to crumble the cake, and ate it with her gloves on, and a pleasant fragrance would cling for some time afterwards to the ends of the short lisle-thread fingers. Sarah had no doubt that her manners as she took leave were almost as distinguished as those of her hostess, though she might have been a wild and shy thing all the rest of the week.

The village of Berwick which she was growing to know had been built at the head of the tidewater of the Piscataqua River, a dozen miles up from Portsmouth. Just below the village this is joined by the Salmon River, and with the great inflow from the sea the two make a magnificent stream, bordered on its seaward course by high wooded banks of dark pines and hemlocks and long green fields that slope gently to lines of willows at the water's edge. Above tidewater the two rivers are barred by successive falls. You hear the noise of them by night in the village like the sound of the sea, and this good water power so near the coast, beside a great salmon fishery famous among the Indians, had brought the first English settlers to the town as early as 1627.

Shipbuilding had become the powerful trade. A little way up the shore from Sarah's house was the shipyard, and not very many years before she was born new vessels had still been launched there. Her grandfather was part owner of most of them, and the names of the ships Perseverance and Pactolus, the barque Sea Duck, the brigs Hero and John Henry, and the schooner Dart had all been familiar to her from babyhood. Her grandfather, Theodore Furber Jewett, was a sea captain. The son of a New Hampshire landowner who traced his American stock back to the founders of Rowley, Massachusetts, in 1639, young Jewett had been bound out as a boy, but had run away and shipped on a whaler for the Pacific. On his return he could boast among his adventures that he and two companions had been left on an uninhabited island to guard stores and secure seals, and had lived there almost a year. The sea was henceforth his life, and at the time of the Embargo he ran a vessel to the West Indies, was captured by an English privateer, and confined on the famous Dartmoor prison ship. After the War of 1812 he settled down, became a ship-owner and merchant, flourished in the West India trade, and married four times..

Sarah kept rich memories of him. Her ears had been quick to hear the news of a ship's having come into port, and she delighted in the elderly captains with their sea-tanned faces who came to report upon their voyages, and to dine cheerfully and heartily with her grandfather, an eager listener to their exciting tales of great storms on the Atlantic, and winds that blew them north-about, and good bargains in Havana, or Barbadoes, or Havre. Sarah listened eagerly too. Her grandfather seemed to be a citizen of the whole geography. And she was always hearing stories of three wars. There was the siege of Louisburg, then the Revolution, in which some of her father's ancestors had been `honest but mistaken Tories,' and her mother's, the Gilmans of Exeter, had `taken a nobler part.' And as for the War of 1812, `the last war,' as everybody called it, it was a thing of yesterday in the town.

She heard too of the great excitement in Portsmouth when French ships came in looking like gardens, for the Frenchmen had lettuces for salads and flowers growing in boxes that were fastened on the decks. Some time later this story took on significance for Sarah. She found an exquisite little water-color painting of a carnation, with the quaintly written request that charming Sally will sometimes think of poor Ribère, who will never forget her. That was all that was left of a tender friendship between a gallant young Frenchman and her grandmother. Sarah found it once among her grandmother's copy books and letters from her girl friends, and love letters from Sarah's grandfather which he sent home to her from sea. She must have been very young when the poor Ribère was so sorry to part from her, for she was married at eighteen, and died at twenty-five. Sarah knew very little about her until she discovered in the garret the brass-nailed trunk that told her these secrets.

This charming Sally, her own namesake Sarah Orne, the daughter of a Portsmouth sea captain, was Sarah's real grandmother, and not the old lady she had known. It was not until after his first wife's death in 1819 that Captain Jewett moved his children up to South Berwick, bought the principal house in the village, the old Haggens mansion, and extended his interests in shipping; building ships and buying large quantities of timber from northward and eastward, and sending it down the river to the sea. This business was still going on in Sarah's childhood, and the manner of its conduct was primitive enough. The barter system still prevailed. The men who brought the huge sticks of ash and pine timber for masts and plank were rarely paid in money, which was of small use in their remote and thinly settled districts. When the sleds and long trains of yoked oxen returned from the river wharves to the stores, they took a lighter load in exchange, of flour and rice and barrels of molasses, of sugar and salt and cotton cloth and tea and coffee; in fact, all the household necessities and luxuries that the northern farms could not supply. They liked to have some money to pay their taxes and their parish dues, if they were so fortunate as to be parishioners, but they needed little besides.

So Sarah came in contact with the up-country people as well as with the sailors and shipmasters. She lingered about the busy stores, and listened to the graphic country talk. When the great teams came in sight at the head of the village street, she ran to meet them over the creaking snow, to mount and ride into town in triumph. But it was not many years before she began to feel vaguely sorry at the sight of every huge lopped stem of oak or pine that came trailing along after the slow-stepping, steaming oxen. She learned far more than she realized of a fashion of life already on the wane, and of that subsistence on sea and forest which was already a forgotten thing in New England when she was grown.

In her grandfather's business household, his second son, Theodore Herman Jewett, unconscious of tonnage and timber measurement, of the markets of the Windward Islands or the Mediterranean ports, 'had taken to his book,' as the old people said, and graduated from Bowdoin, and then studied medicine with Dr. Perry in Exeter, and gone away to Philadelphia to take his degree, and had felt that devotion to the study of his science which ended only with his life. He was made Professor of Obstetrics at Bowdoin, his contributions to scientific journals were numerous and notable, and he was President of the Maine Medical Society for many years. But chiefly he was the man whom his daughter attempted to draw in her story of 'A Country Doctor,' though she knew her portrait inadequate to the gifts and character of the man himself. He settled to practise in Berwick, and was married at twenty-seven to Caroline Frances Perry, the gentle delicate daughter of his former teacher and Abigail Gilman, both of old Exeter families. His wife gave birth to three girls, Mary, Sarah, and Caroline.

Dr. Jewett had inherited from his father a wide knowledge of human nature, and from a strain of French blood in his mother's ancestry a lightness and gaiety of heart. Through all the heavy responsibilities and anxieties of his busy professional life and the steady drain on his energy, he remained amazingly young, even boyish. His visits to his patients often refreshed them as much by the touch of his personality as by the medicines he brought. Sarah knew many of those patients on the lonely inland farms and in the fishermen's cottages at York and Wells. She used to follow her father about silently, like an undemanding little dog, content to be at his side. When he let her ride up-country with him, she sometimes waited outside with the horse, but other days she went and sat in the kitchen and ate the piece of gingerbread that had been baked for `the doctor's girl.' She had no consciousness of watching or listening, or indeed of any special interest in the houses or people. But her father kept pointing things out to her.

He talked to her about books, too, and gave her her first and best knowledge of them by his own delight and dependence upon them, and ruled her early attempts at writing by the severe simplicity of his own good taste. 'Great writers don't try to write about people and things, they tell them just as they are.' How often such words fell upon Sarah's young ears without her comprehending them. But while she was too young and thoughtless to share in his enthusiasms for Fielding and Smollett, `Don Quixote' and 'Tristram Shandy,' her mother was leading her into the pleasant ways of 'Pride and Prejudice' and 'Cranford.' The old house was also well provided with thick shelves of leather-bound books of a deeply serious nature, sermons and histories, and in her curiosity she had soon pried into everything from her father's medical tomes to the 'Arabian Nights.' She could find something vital in even the driest and in the more entertaining she was completely lost.

It was a different matter when Mary and she went to school at the Berwick Academy on top of the hill. She liked the other children who came there not only from the village, but from as far away as Cuba, since the school was already seventy years old and of a high name. She remembered the breathless thrill when these friends opened packages from the West Indies. She and Mary enjoyed the guava jelly, and her sister has confessed, `I'm afraid we enjoyed the cigarettes.' Sarah also liked to read and to write verses, but she was given to long childish illnesses and to instant drooping whenever she was shut up in school. She had apparently not the slightest desire for learning, but her father was generally ready to let her be his companion on those long drives about the country. He was always amused and patient with this heedless child, inclined far more to dreams than to accuracy. He was impatient only with affectation or insincerity. He lifted her up over the carriage wheel, and jumped in himself from the other side. He took the reins in his firm hand, and gave a cluck to the horse. The carriage leapt forward (her father's driving was the admiration of the village), and Sarah snuggled against his shoulder and breathed a little sigh of satisfaction. She was lost in radiance for the rest of the afternoon. Only a great many years later she recalled wise things her father had said and the things he had made her see.

Suddenly they turned off the main road into a lane, and pulled up before a low-roofed white wooden house. The noise of wheels grating over rocks brought a thin girl around the corner from the vegetable patch behind. She was hardly older than Sarah, but was carrying a hoe. When she saw it was the doctor she laid it down, and went inside the door without a word. Sarah's father took his bag from under the seat, jumped down from the carriage, and followed her. Presently the door opened once more, and the girl picked up her hoe, and disappeared again around the corner. Sarah looked in vain for any truckle-cart in the yard, or a doll, or bits of broken crockery laid in order on a rock. She knew that this girl's mother was a cripple, that she had to sit all day long in a chair, and couldn't even lift her food to her mouth. Sarah never went into this house, but once she had caught a glimpse of the woman through the open door, sitting back from the window, but from where she could look down the lane. A half-withered rose lay on the table beside her. Sarah knew that some days nobody came up the lane, and that the woman's only entertainment must have been to watch the wild birds that ventured near the house and the clouds that blew across the sky. Sarah had found her first anemones in this lane.

As they were leaving, the man came up, driving a team. He was just back from hauling timber, and took the doctor aside to talk. Sarah caught only broken sounds above the scraping of the horses . . . `. . . buried to-day that was struck by lightnin' . . . comin' acrost a field when a great shower begun. The lightnin' stove through his hat and run down all over him, and ploughed a spot in the ground.'

They stopped at one or two other places farther along. Sarah observed how almost every house had plots of gay flowers in front, carefully hedged with barrel staves to keep out the miscreant hens. Calves were tethered in shady spots, and puppies and kittens were adventuring from doorways. They met some people, walking sedately, dressed in their best clothes. They were coming from the funeral; the dead man's house was down the road. The occasion was nearly ended by this time; the funeral supper had been eaten and the borrowed chairs were being set out in the yard in small groups. The new grave showed plainly in the field near by. As they turned home, she saw the last of the columbines clinging to a hillside. Meadow rue and red and white clover were just coming into bloom down in the small fenced meadows belonging to the farms. The buttercups were thicker than the grass, and mulleins stood straight and slender among the pine stumps.

The carriage creaked up Great Hill. The last June sunlight was catching the fields of young grain and the wooded slopes away toward the dim New Hampshire hills on the northern horizon. Mount Agamenticus stood seaward, dark with its pitch pines, and the far sea itself, blue and calm, ruled the uneven country with its unchangeable line.

II.

Contents

HER grandfather died in her eleventh year, and presently the Civil War began. From that time the old village life was at an end. The provincial character was fading out. Shipping had long been at a disadvantage, and no more bronzed captains were coming to dine now and bringing great red jars of olives from the Indies, and bags of filberts or oranges to delight a child. Sarah remembered thinking it very odd that the smooth green bank where the dandelions were so bright in the spring should still be called the shipyard, and wondering why old people kept referring to that corner of the town as the Lower Landing, since nothing ever seemed to land except the fleets that she and the others built of chips and shingles. Once in a great while a stray packet or a gundalow with its high, peaked lateen sail still brought some freight up the river, but the shipwright's hammer would never be heard again. Berwick was no longer an inland port, a busy artery between Santo Domingo and London. It was an up-country station on a branch railway line, grappled by bonds of steel and wire to Lawrence and Lynn.

Throughout New England the invigorating air that Emerson and Thoreau had breathed was clogged with smoke. A mile away from Sarah's house the textile mills at Salmon Falls were employing larger and larger numbers, and rows of drab rickety houses were growing like mushrooms overnight. The native village folk were slowly crowded out by Irish immigrants. Their hearts were not destined to know the bold resolve and high achievement of Sarah's grandfather. They were not to glean strange knowledge of the world from the lips of friends who had been to Archangel and Marseilles, but to learn their rumors fourth-hand from a dingy local paper. They clung grimly to their stony farms and mouldering fishing shacks and worked out their uneventful lives cheered only by the bright memory of the past. A woman was counted lucky if she could find a husband in the dwindling countryside, and her son was also lucky if he could land a job in the mill along with the foreigners, and didn't have to shoulder a lean pack, and take the cars for the West. Sarah Jewett was growing up in a period of decline. The village's proud feeling of self-sufficiency was gone forever.

Naturally she did not realize all these changes until some time afterwards. By the end of the war she had become a tall slender girl, never very strong, but full of bursts of energy, a deep flush covering her dark cheeks, a quick fire in her large brown eyes. She spent her days outdoors whenever she could. Mud or no mud she saddled Sheila, whose name she pronounced in the German manner because she occasionally shied, and went off in search of two or three strips of dry sandy road where she could have a `hurry.' She carefully avoided puddles for an hour or so, but finally pulled up her long skirt and splashed home contentedly. She loved the loneliness of silent, forgotten places, to sit with her back against the fireplace of the deserted house that had once been the parsonage of the North Parish, and wonder what kind of people had lived there; to let her boat drift after a violent spurt, and look up through the trees at the sky or at their reflection in the ripples of the oars; or to let it stop altogether until she could watch the first fish come back to their playground on the yellow sand and gravel, and the frogs, that had flopped into the water at her approach, poke their heads out a little to croak indignantly. The swallows darted along the surface of the water after insects, and she saw a drowned white butterfly float by, and reached out for it: it looked so frail and woeful in the river.

Many years later she wrote in a letter to Whittier, 'Nobody has mourned more than I over the forsaken farmhouses which I see everywhere as I drive about the country out of which I grew, and where every bush and tree seem like my cousins.' And one of her first real sorrows came from these trees. She was always saying how certain of them seemed to have just as much character as people. And then in one of her early sketches she had to record: `The woods I loved best had all been cut down the winter before. I had played under the great pines when I was a child, and I had spent many a long afternoon under them since. There never will be such trees for me any more in the world. I knew where the flowers grew under them, and where the ferns were greenest, and it was as much home to me as my own house. They grew on the side of a hill, and the sun always shone through the top of the trees as it went down, while below it was all in shadow.' The increasing destruction of her world gave her a hunted feeling like the last wild thing left in the woods.

Autumn days she would take Jock or Crabby, and walk. The wind blew straight in from the sea. There was a tinge of red still lingering on the maples, and her dress brushed over the late golden-rods, while old Crabby, who seemed to have taken a new lease of youth, jumped about wildly and raced after the birds that flew up from the long brown grass -- the constant chickadees who would sing before the coming of snow. But this day brought no hint of winter. She leapt over a fence, and took great strides down the valley. She was off to call on some particular friends. After several miles she climbed a low hill, and went down through the familiar pasture lane. At that moment she saw her father drive away up the road, just too far to make him hear her when she called. But she reflected that he would come back again over the same way, and in the meantime she could pay her visit.

The house was low and long and unpainted with a great many frost-bitten flowers about it. Some hollyhocks were bowed down despairingly, and the morning-glory vines appeared more miserable still. Sarah heard a loud whirring noise inside, and through the open door saw Miss Polly Marsh and her sister, Mrs. Snow, stepping back and forward together spinning yarn at a pair of big wheels. They went together like a pair of horses, and kept step with each other to and fro. They were about the same size, and were cheerful old bodies, looking a goad deal alike, with their checkered handkerchiefs over their smooth gray hair, their dark gowns made short in the skirts, and their broad feet in gray stockings and low leather shoes without heels. They stood straight, and though they were quick at their work they moved stiffly. They were talking busily about some one.

'I could tell by the way the doctor looked that he didn't think there was much of anything the matter with her,' said Miss Polly Marsh. '"You needn't tell me," said I the other day, when I see him at Miss Martin's. "She'd be up and about this minute if she only had a mite o' resolution." And says he, "Miss Polly, you're as near right as usual,"' and the old lady stopped to laugh a little. 'I told him that wa'n't saying much,' she said, with an evident consciousness of the underlying compliment and the doctor's good opinion. 'I never knew one of that tribe that hadn't a queer streak and wasn't shif'less, but they're tougher than ellum roots,' and she gave the wheel an emphatic turn, while Mrs. Snow, reaching for more rolls of wool, happened to see Sarah.

'Wherever did you come from?' they asked in great surprise. 'Why, you wasn't anywhere in sight when I was out speaking to the doctor,' said Mrs. Snow. 'Well, now, we're pleased to see ye.'

Sarah begged them not to stop spinning, but they insisted they should not have turned the wheels a half-dozen times more, even if she had not come, and they pushed them back to the wall before they sat down to talk with her over their knitting. Miss Polly was Sarah's special friend, for she was a famous nurse, often in demand all through that part of the country, and had come to take care of her during a long illness one winter. Now she brought her a stout pitcher of sweet cider, and the three of them sat together, gossiping. Sarah told all the village news she could think of, while Miss Polly darted from her chair occasionally to catch stray wisps of wool which the breeze through the door blew along from the wheels. A gay string of red peppers hung above the high mantelshelf, and the woodwork in the room had never been painted and had grown brown with smoke and scouring. A bouquet of asparagus and some late sprigs of larkspur and white petunias stood on the table, and a Leavitt's Almanac lay on the county paper that was itself lying on the big Bible, of which Miss Polly made a point of reading two chapters every day `in course.' Sarah remembered having heard her say despairingly one night to herself, `I don't know but I may skip the Chronicles next time,' but didn't believe she ever had.

`Who was it you were talking about as I came in?' she asked. `You said you didn't believe there was much the matter with her.' And Miss Polly clicked her needles faster, and told her it was Mary Susan Ash, over by Little Creek.

`They're dreadful nervous, all them Ashes,' said Mrs. Snow. `You know young Joe Adams' wife, over our way, is a sister to her, and she's forever a-doctorin'. Poor feller! he's got a drag. I'm real sorry for Joe, but land sakes alive! he might 'a known better. I've lost every mite of patience with her. I was over there last week one day, and she made out she'd got the consumption, and she told how many complaints she had, and what a sight o' medicine she took, and she groaned and sighed, and her voice was so weak you couldn't more than just hear it. I stepped right into the bedroom after he'd been prayin' with her, and was takin' leave. You'd thought, by what he said, she was going right off then. She was coughin' dreadful hard, and I know she hadn't no more cough than I had. So says I, "What's the matter, Adeline? I'll get ye a drink of water. Somethin' in your throat, I s'pose. I hope you won't go and get cold and have a cough." She looked as if she could 'a' bit me, but I was just as pleasant 's could be. Land! to see her laying there, I suppose the poor young feller thought she was all gone. I wish he had seen her eating apple dumplings for dinner. She felt better 'long the first o' the afternoon before he come. I says to her, right before him, that I guessed them dumplings did her good, but she never made no answer. She will have these dyin' spells. Poor Joe, he come over for me last week another day, and said she'd been havin' spasms, and asked me if there wa'n't somethin' I could think of. "Yes," said I, "you just take a pail o' stone-cold water, and throw it square into her face. That'll bring her out of it." And he looked at me a minute, and then he burst out a-laughin' -- he couldn't help it. He's too good to her. That's the trouble.'

`You never said that to her about the dumplings?' asked Miss Polly, admiringly. `Well, I shouldn't ha' dared,' and she rocked and knitted faster than ever, while they all laughed. `Now with Mary Susan, it's different. I suppose she does have the neurology, and she's a poor broken-down creature. She had a dreadful tough time of it with her husband, shif'less and drunk all his time. Noticed that dent in the side of her forehead, I s'pose? That's where he liked to have killed her; slung a stone bottle at her.'

'What!' gasped Sarah, very much shocked.

`She don't like to have it inquired about, but she and I were sittin' up with 'Manda Damer one night, and she gave me the particulars. I knew he did it, for she had a fit o' sickness afterward. Had sliced cucumbers for breakfast that morning, he was very partial to them, and wanted some vinegar. Happened to be two bottles in the cellar-way just alike, and one of them was vinegar and the other had sperrit in it at hayin'-time. He takes up the wrong one and pours on quick, and out come the hayseed and flies, and he give the bottle a sling, and it hit her there where you see the scar. Might put the end of your finger in the dent. He said he meant to break the bottle agin' the door, but it went slantwise, sort of. I don't know, I'm sure ..... She had good prospects when she married him. Six-foot-two and red cheeks and straight as a Noroway pine ---'

`Here comes your father,' broke in Mrs. Snow. `Now we mustn't let him get by or you'll have to walk way home.' And Miss Polly hurried out to speak to him, while Sarah gathered up her fading bunch of fringed gentian, and followed her with Mrs. Snow.

She could talk to her father now, not as a daughter but as one of his friends. They ranged from Miss Perkins' sciatica and the state of the poor on the town farm to theology and law and nonsense. She knew his papers, his books, his medicines almost as thoroughly as if she were a doctor herself. Not a corner of his mind or work was foreign to her. No wonder that in later years she always said, `I look upon that generation as the one to which I really belong -- I who was brought up with grandfathers and grand-uncles and aunts for my best playmates. They were not the wine one can get for so much the dozen now.' It was not only the companionship of her father, but that whole fading world which continued to hold the center of her affections. Near the turn of the century she was writing to Sara Norton: `I have had to go to Exeter several times lately, where I always find my childhood going on as if I had never grown up at all, with my grand-aunts and their old houses and their elm trees and their unbroken china plates and big jars by the fireplaces. And I go by the house where I went to school, aged eight, in a summer that I spent with my grandmother, and feel as if I could go and play in the sandy garden with little dry bits of elm-twigs stuck in painstaking rows. There are electric cars in Exeter now, but they can't make the least difference to me.'

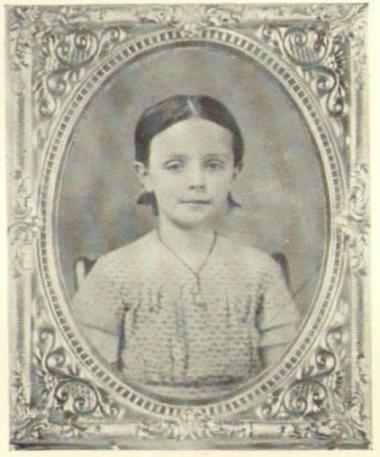

Sarah Orne Jewett at the Age of Eight

From an ambrotype

No difference to her, for her memories were secure. But New England wasn't. When Miss Jewett grew fully conscious of what was happening she stated: `People do not know what they lose when they make away with the reserve, the separateness, the sanctity of the front yard of their grandmothers. It is like writing down the family secrets for any one to read; it is like having everybody call you by your first name and sitting in any pew in church, and like having your house in the middle of a road, to take away the fence which, slight as it may be, is a fortification round your home. More things than one may come in without being asked; we Americans had better build more fences than take any away from our lives.'

Long before she had such reflections the world of her own imagination had become more real to her than any other. When she was thirteen or fourteen she had read 'The Pearl of Orr's Island,' Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel about the people who lived in the decaying shipless harbors of Maine. Its first chapters opened her eyes. Her father had already instilled in her his keen interest in the quiet village life and the dull routine of the farms. And now she began to follow the old shore paths from one gray, weather-beaten house to another more eagerly than ever before.

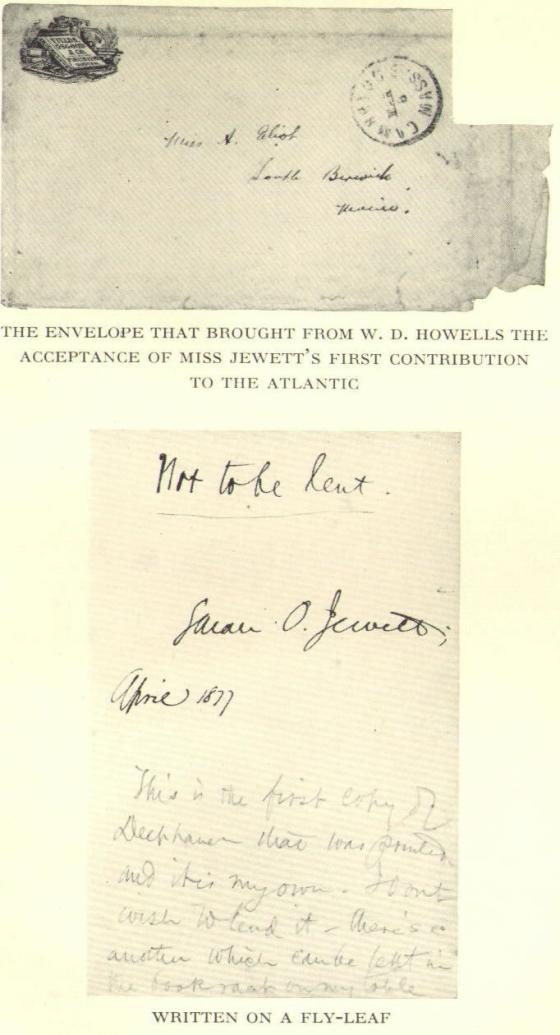

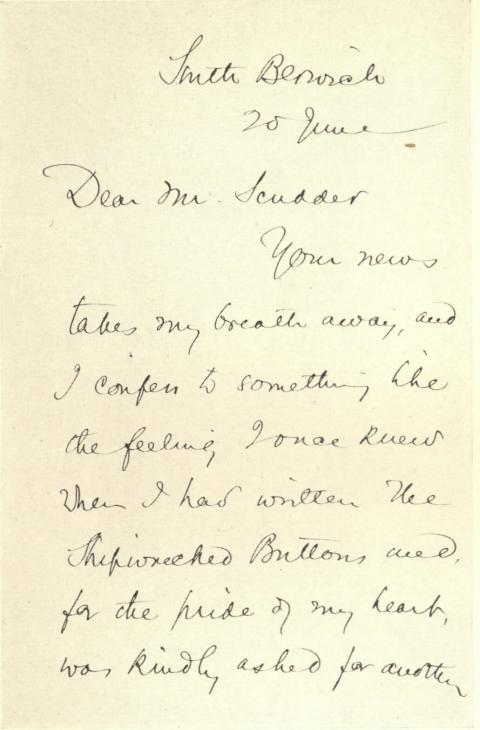

She wrote down the things she was thinking about. At first she generally put them into rhymes for prose seemed more difficult. Then she began telling herself stories, and giving them fancy names, `The Girl with the Cannon Dresses' and `The Shipwrecked Buttons.' One summer she hit on the bold scheme of sending some of them to a children's magazine, `Our Young Folks' or `The Riverside.' She was very shy of speaking about such audacity to any one at home, and pledged Mary to utter secrecy. She even sent off her first manuscripts under an assumed name, Alice Eliot. Then came the ordeal of having to ask the postmistress for those mysterious and exciting editorial letters, which she announced on the post-office list just as though Miss Alice C. Eliot had been a stranger in the town.

Horace Scudder, editor of `The Riverside,' was very kind. He accepted `The Shipwrecked Buttons' at once, and sent her a nice letter of encouragement. She wrote a far more elaborate story about how a New England girl's father had brought home company unexpectedly, among them a young Englishman, Mr. Bruce. The waitress was out so his daughter Kitty blithely took her place. The next year Mr. Bruce was naturally amazed to meet Kitty in Baltimore society, but the ensuing complications were at last unravelled, and marriage was the result. Sarah Jewett, made brazen by success, sent this to `The Atlantic Monthly,' of which James T. Fields was editor. She received some notes of suggestion without any signature. She wrote back, addressing herself `to the Editor with the fine handwriting.' His name turned out to be William D. Howells. `Mr. Bruce' was accepted. It appeared in the `Atlantic' for December, 1869.

Mr. Scudder hastened to send her a

letter of congratulations. He ventured on a word or two of

criticism, but quickly checked himself. Whom was he writing to?

He had thought her some young girl just beginning to make up

stories for children, and here she had turned out to be a

contributor to the most distinguished magazine in America. He

apologized gracefully and got this answer:

SOUTH

BERWICK

30th Nov., 1869

DEAR SIR:

Thank you for your kind note and

especially for your criticisms on my two Stories. They will help

me I know. You were right about Mr. Bruce, and if I were talking

instead of writing I could tell you of ever so many other things

that might have been very different. I couldn't expect to be

perfect. In the first place I couldn't write a perfect Story,

and secondly I didn't try very hard on that. I wrote it in two

evenings after ten when I was supposed to be in bed and sound

asleep, and I copied it in part of another day. That's all the

work I 'laid out' on it. It was last August and I was nineteen

then, but now I'm twenty. So you see you are 'an old hand' and I

'a novice' after all.

Do you remember in 'Mr. Bruce,' I made

'Elly' say that like Miss Alcott's 'Jo' she had the habit of

'falling into a vortex'? That's myself, but I mean to be more

sensible. I mean to write this winter and I think you will know

of it. I like the 'Riverside' and what you have written, and you

are delightful to have dear old Hans Andersen. I don't see the

'Riverside' regularly though. I'm not a bit grown up if I am

twenty, and I like my children's books just as well as ever I

did, and I read them just the same. I'd like to see the Buttons

in print; you said the 18th I think. It's a dreadful

thing have been born very lazy, isn't it, Mr. Scudder? For I

might write ever so much; it's very easy for me, and when I have

been so successful in what I have written, I ought to study -

which I never did in my life hardly, except reading. And I ought

to try harder and perhaps by and by I shall know something and

can write really well. - There was no need for me to write this

note and I'm a silly girl? I know it. But your letter was so

very nice and you are kind to be interested in my stories. So I

beg your pardon and will never do so any more. You said you had

seen my name before. It was some verses - 'The Old Doll' -- two

years ago, I think. I must hunt them up. I believe they were

very silly.

Yours very respectfully and gratefully

`ALICE ELIOT'

Success had by no means deprived Horace Scudder of his valuable contributor. Within a month he heard again:

DEAR SIR:

I found this the other day and I liked

the idea and have written it all over except for two verses.

Will it do for you? . . . I can't tell about the verses I write

half as well as I can the stories and I don't know whether this

is good for anything, or not. But you can tell in two minutes

and if you think it's very silly, and I'm weak-minded to have

sent it, imagine me asking your pardon with a most penitent

expression of countenance. Thank you for the `Riverside' which

came yesterday.

Very respectfully

ALICE ELIOT

P.S. I've been reading your `Stories from My Attic,' and it's very nice .... I was quite affected when I found the furniture went in procession down stairs and that you had to go away. My local attachments are stronger than any cat's that ever mewed and I should break my heart if I had to leave my room, which is called bad and disrespectful names by the rest of the family, however! I think I shall write a story about it someday by way of warning to young women in general.

Her horizon was widening. She took more frequent trips to Boston. She made long visits with her friends in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, and went as far west as Green Bay, Wisconsin, one summer, and was away from home for over six months. But the prairies seemed to her like reading the same page of a book over and over, and she was glad to get back again to her Maine hills. She became acquainted with the editors of the `Atlantic,' and was introduced through them to nearly everybody. Mr. Howells, who was already growing prominent as a novelist, was particularly friendly, and Sarah found more than one occasion to say:

I cannot wait any longer before

writing you a note to thank you for `Their Wedding Journey.' I

am enjoying it so much and this last number is so good! It seems

unnecessary, though, for you to improve, for people were so

satisfied before, and there are so many dear stupid writers who

will go on and on in the same fashion till they die. I have

taken great pleasure in the November number for I had been quite

low-spirited! Berwick has grown quite uninteresting to me for

once in its life, and everybody is distressingly grown-up and I

have `nobody to play with.' I have been writing some children's

stories for the `Independent,' and the state of my mind is

shadowed forth in the last one, `Half-done Polly,' which is

severely moral. I dare say you will not be able to account for

my telling you this, but I suppose it is another illustration of

your `pleasures of autobiography so dear to all of us' -- I

don't know if I have quoted it right, but it made a great

impression upon me. I once went over part of the `Wedding

Journeyin'' route myself and I have enjoyed that part

particularly. I have grown very ambitious of late and wonder

continually if by any possibility I shall write so charmingly by

and by. I am diverting myself at present by reading Froude's

History, but I find myself planning my `fall campaigns' in the

midst of important acts of Parliament and it goes off slowly!

Yours most sincerely,

Sarah O. Jewett

South Berwick;

17th Oct., 1871

Life was becoming much more complicated. As she gave herself more and more to her friends she grew dependent on them, and suddenly found Berwick lonely. A flood of new problems presented themselves, and she was forever getting tangled up in her emotions, and then bursting out of the house, and riding too fast for good manners, and then having to try all over again not to let her boyishness make her rude and unladylike. She was fortunate in having met old Professor Theophilus Parsons one August day at Wells, and having developed an instant fondness for him. He was Professor of Law at Harvard, and an ardent Swedenborgian, the leader of the New Church. The kindly sureness of his faith both steadied and refreshed her. She sent him letters, endless pages long, telling him everything that came into her head, and then writing at the close that he needn't be afraid, for she didn't always expect an answer. She told him again and again how much his books were helping her to find the meaning of life; that she had been out in the woods hunting for cardinal flowers; that she was studying Chambers' Cyclopedia with diligence and having music lessons and German lessons, but was pretty sure that it was better not to neglect some other things for the sake of her studies, since she learnt fastest by observation and never would be much of a student of books; how she had been ignominiously run over on Broadway on a visit to New York, and just escaped being killed; how she had been contented in her outdoor childhood and was almost sure she could live the same life now, although she wasn't sure she would find quite the infinite satisfaction she used in damming brooks; how she was beginning to feel very grand for she had been advertised among the `crack contributors' to the 'Independent'; how she wished there was just one girl in Berwick she might have for a friend.

Since that bold prank of Alice Eliot's, writing stories was not quite the same droll game it had been, and it seemed to confuse all the rest of life besides. Some time after she had had a second story, `The Shore House,' accepted by the `Atlantic,' in the fourth year after `Mr. Bruce,' she was saying to Professor Parsons: 'I amused Mary very much this morning while we were driving together by saying a certain apple tree in a field was just like me. It hadn't been pruned and was a wilderness of "suckers" and unprofitable little scraggly branches. I said: "I wish I grew in three or four smooth useful branches instead of starting out here, there and everywhere, and doing nothing of any account at any point." I seem to have so many irons in the fire and I grow worried when I think of it. I must ask you about this when I see you. It's hard for me to know what to do: I don't like to shut myself up half of every day and say nobody must interfere with me, when there are dozens of things I might do. I have nothing to do with the house-keeping or anything of that kind, but there are bits of work waiting all the time that use up my days. I hate not to do them and I'm afraid of being selfish and shirking -- and yet -- well, I'll not talk any more about that, but let it wait.'

There were so many things she wanted to talk over with every one that she started pouring out some of them in the middle of what she had meant to be a short business note to Mr. Scudder about copyrights. Her remarks were not quite in the breezy tone of the author of `The Shipwrecked Buttons.' She said: `I have been writing for the "Independent" since I saw you. Not very much, however, for I don't think I need the practice of writing so much as I need study, and care in other ways. I think you advised me long ago not to write too much, or to grow careless? I am getting quite ambitious and really feel that writing is my work -- my business, perhaps; and it is so much better than making a mere amusement of it as I used. I sent you some sketches I gave a paper published at our Hospital Fair in Portland not long ago. I am really trying to be very much in earnest and to do the best I can, and I know you will wish me good luck. I have had nothing to complain of, for the editors have never proved to be dragons, and I even find I have achieved a small reputation already. I am glad to have something to do in the world and something which may prove very helpful and useful if I care to make it so, which I certainly do. But I am disposed to longwindedness!' -- and she finished her question about copyrights.

But it did no good to try to dam her tumbling thoughts with a jest like that. Ten days later she was writing again:

SOUTH BERWICK 13 July, 1873

MY DEAR MR. SCUDDER:

In the first place I think this letter

will need no answer. Does not this announcement help you to

begin to read it with a pleasanter feeling? The truth is I wish

to talk to you a little about my writing. I am more than glad to

have you criticize me. I know I must need it very much and I

realize the disadvantages of never hearing anything about my

stories except from my friends, who do not write themselves, and

are not unexceptionable authorities upon any strictly literary

question. I do know several literary people quite well, but

whenever they read anything of mine I know that they look down

from their pinnacles in a benignant way, and think it is very

well done `for her,' as the country people say. And all this is

not what I want.

Then it is a disadvantage that I have been so successful in getting my nonsense printed! I am so glad to have you show me where I fail, for I wish to gain as fast as possible and I must know definitely what to do. But Mr. Scudder, I think my chief fault is my being too young and knowing so little! Those sketches I sent you were carefully written. Of course they were experiments and I could perhaps have made them better if they could have been longer. Those first stories of mine were written with as little thought and care as one could possibly give to write them at all. Lately I have chosen my words and revised as well as I know how: though I always write impulsively -- very fast and without much plan.

And strange to say this same fault shows itself in my painting, for the more I worked over pictures the stiffer and more hopeless they grew. I have one or two little marine views I scratched off to use up paint and they are bright and real and have an individuality -- just as the `Cannon Dresses' did. That is the dearest and best thing I ever have written. `The Shore House' which Mr. Howells has, reminds me of it and comes next. I wrote it in the same way and I think it has the same reality. I believe the only thing he found fault with was that I did not make more of it. `The characters were good enough for me to say a good deal more of them.' But I don't believe I could write a long story as he suggested, and you advise me in this last letter. In the first place I have no dramatic talent. The story would have no plot. I should have to fill it out with descriptions of character and meditations. It seems to me I can furnish the theatre, and show you the actors, and the scenery, and the audience, but there never is any play! I could write you entertaining letters perhaps from some desirable house where I was in most charming company, but I couldn't make a story about it. I seem to get very much bewildered when I try to make these come in for secondary parts. And what shall be done with such a girl? For I wish to keep on writing, and to do the very best I can. It is rather discouraging to find I lose my best manner by studying hard and growing older and wiser. Copying one's self has usually proved disastrous. Shall not I let myself alone and not try definitely for this trick of speech or that, and hope that I shall grow into a sufficient respectability as the years go on?

I do not know how much real talent I have as yet, how much there is in me to be relied upon as original and effective in writing. I am certain I could not write one of the usual magazine stories. If the editors will take the sketchy kind and people like to read them, is not it as well to do that and do it successfully as to make hopeless efforts to achieve something in another line which runs much higher? You know the spirit in which I say this, for you know my writing has until very lately been done merely for the pleasure of it. It is not a bread and butter affair with me, though such a spendthrift as I could not fail to be glad of money, which has in most instances been lightly earned. I don't wish to ignore such a great gift as this God has given me. I have not the slightest conceit on account of it. Indeed I believe it frightens me more than it pleases me.

Now it has been a great satisfaction

to have said all this to you. Please look upon it as a slight

tribute to your critical merits which no one can appreciate more

heartily than I, and remember that I told you in the beginning

there would be no questions which would need answering. Thank

you for telling me of your engagement though I had heard of it

long ago from some Boston friend and I had half a mind to speak

of it when I was writing you. I am very glad now to send you my

best wishes. I shall like exceedingly to see Miss Owen, and I

congratulate you both with all my heart.

Yours most sincerely

SARAH O. JEWETT

`The Shore House' was a very different story from `Mr. Bruce.' Instead of making her effect depend upon the complications arising from a schoolgirl's prank, she wrote a straightforward account of a spacious country house like her own, of the memories of voices and laughter that had sounded through its halls, of the bustling village life that surrounded it. Mr. Howells, who had now succeeded Mr. Fields as editor of the `Atlantic,' was unstinted in his praise. He detected a note of authority in its quiet lines, and urged her to do more, for he thought that she had found her true bent in realism of just this sort. Miss Jewett thought so too. Other aspects of life in the village she had called Deephaven were already flickering in her mind. There was Mis' Kew the wife of the lighthouse keeper, and Mis' Dockum and the Widow Jim; and the gaunt captains, and she would like to write about a day of cunner-fishing, and the circus over at Denby, and Black Rock and the long sands where a ship had been driven ashore in the night, and the cliffs and pebble beach, and the subtle variance of wind and tide, of sun and shadow, that made each day in her Shore House different from every other.

This inscription on the flyleaf of one of Jewett's

copies of Deephaven reads after the date:

This is the first copy of Deephaven that was printed

and it is my own. I don't wish to lend it --

There is another which can be lent in the bookrack

on my table.

She was almost startled to discover how swiftly this seed unfolded in her mind. All the things she had loved in childhood, all the facts of life she had observed, now seemed to fuse and recombine in this village of her fancy. Deephaven. She could see it shining plain. It was not a bleak place. The dwindling countryside was never bleak to her. She knew its sorrows and suffering, who better than the daughter of the country doctor? But to her eyes these were also bathed in a delicate radiance that seemed to emanate from the soil itself. `Being a New Englander,' she once wrote as the opening sentence of one of her sketches, `it is natural that I should first speak about the weather.' When she surveyed her world at the end of a long winter, the drab hills with their sodden snowdrifts and patches of heavy mud did not weigh on her with a sense of weariness or frustration, for she thought they looked `like big leopards and tigers ready for a pounce at something, with their brown and white spots.' They were not dead and oppressive, but alive, alive as the first hepaticas who always struck her like some people she knew, `very dismal blue, with cold hands and faces.' She was aware now, as she commenced to fill in the outlines of Deephaven, of how many things in nature stood as symbols to her mind. The roses blooming at the farm doors -- she could not look at them without reflecting on the countless lovers who had picked them on Sunday evenings, and carried them along the roads or by the pasture footpaths, hiding them clumsily under their Sunday coats if they heard any one coming. And in this land where the sea nipped many a life before its prime, how often the white roses had been put into paler hands and had withered there . . . . November, which was called by others a dreary and foreboding month, thrilled her by its swift changes of storm and sunlight. After a period of piercing and sombre cold a day would break almost sultry. The air was soft and damp and Sarah could see that the buds of the willows had even been beguiled into swelling a little, so that there was a fragile bloom over them, and the grass looked as if it had been growing green of late instead of fading steadily. It seemed like a reprieve from the doom of winter. Its sudden beauty made her catch her breath.

Now, as she tried to set down her impressions of the people as accurately as possible, she realized for the first time the full importance of her father's influence. Again and again the sound of his voice came to her as she bent over her paper, quietly explaining some detail that had fascinated him in their surroundings. She grew to believe that he had recognized long before herself in what direction the current of purpose in her life was setting. She found herself equipped at the start of her career with what many strive unsuccessfully ever to gain, an almost complete knowledge of her environment. As her letters to Horace Scudder revealed, she was groping for the exact angle from which to express herself. Being a New Englander, she was naturally confused at the start by the differing claims of art and ethics. She had written many schoolgirlish paragraphs to Professor Parsons about wanting to be good and true so that the self in her stories would be sympathetic, and so that they would never fail to be helpful and strong because there was no life running through them, and her own heart cold and selfish. She had grown beyond that point now, and although, in her letters to him, she was still puzzling over the place that `moralizing' should occupy in her work and hoping that Deephaven might `help people to look at "commonplace" lives from the inside instead of the outside, to see that there is so deep and true a sentiment and loyalty and tenderness and courtesy and patience where at first sight there is only roughness and coarseness and something to be ridiculed,' at least she could say: "For myself, I like best to have the moral in the story - to make the character as apparent as I can, as one feels instinctively the character of the people one meets. I always feel when I say anything directly as if it were awkward and that if the story itself doesn't say it, it is no use to put it in afterward.' Clumsily expressed perhaps, and far from fully formulated, but Sarah Jewett had cleared the first barrier that blocks the way of nearly every American artist. She was not going to write moral tales. She was going to write - not about life, but life itself.

Her material was deeply embedded in her heart. She had simply to allow her recollections to rise slowly to consciousness and unfold, like a moonflower in the quite evening. Those endless talks with Miss Polly Marsh, and with Captain Dan over at Wells…. The crusty talk of the fishermen was so familiar to her ears that she could reconstruct its nasal cadence almost at will. But her way of composing was not calculated and deliberate like this. She had said that she always wrote impulsively, and in a sense she was still the girl who scribbled down sudden stories out of what she knew. After the whole series of Deephaven sketches had appeared, she wrote to Horace Scudder: 'No. I haven't dug a clam all summer, for what with the Centennial and a visit in New York in June and the house filled with visitors ever since we came home in July, I have only been down to the shore half a dozen times and only for the day, which doesn't count with me. But I am going down directly to spend a week, and then I know where to go for those clams and where to get an old dory with as many leaks as a basket. And I know where the cunners hold county conferences out in the harbour - where two other little boys and I caught a hundred and thirty in just no time at all one day last summer. This is all in York, which reminds me of my dear Deephaven, though that was "made up" before I had ever stayed overnight in York, or knew and loved it as I do now. Since the Shore House was written I have identified Deephaven with it more and more. Still I don't like to have people say that I mean York when I say Deephaven.' It was out of such expeditions as the one she was anticipating here that Deephaven grew, springing as naturally as bayberry and everlasting from her Maine soil.

The sketches were a real success. The very first one had called forth favorable comment from the New York `Nation,' which, under the editorship of E. L. Godkin, was the one significant critical journal of the time. After they had been printed in the `Atlantic' over a period of two or three years, Mr. Howells kept urging her to gather them together into a book. That meant a great deal of rewriting and rearranging, work that left her very tired since she was not used to it, and which strung out for nearly a year as she had several spells of sickness and was laid up for almost half the time. Then came the venture of interviewing publishers, and both Roberts Brothers, to whom she was introduced by Professor Parsons, and Mr. Osgood, to whom she had a letter from Mr. Howells, were so very kind that she was almost distressed in making up her mind between them. She finally decided on the latter, since the `Atlantic' was after all the mainsail of her craft, and Mr. Howells had been so thoughtful and taken so much trouble for her. In lean months of further revising and proof-reading the book grew duller by the hour to her tired eyes. At last she tossed it into her valise and took it to Boston herself in the beginning of the winter of 1877. She had planned to stop and pay some visits and have a gay time, but she had overworked and went home tired and aching after a few days.

`Deephaven' came out in the spring

between pleasant tan covers adorned with a bunch of cat-tails,

and bore the inscription, `I dedicate this story of out-of-door

life and country people first to my father and mother,

my two best friends, and also to all my other friends, whose

names I say to myself lovingly, though I do not write them

here.' It sold well and brought her generous compliments from

every one, and even gained a good deal of attention quite

outside of the Boston circle. A happy smile carne to her lips

when an old country friend of her father's spoke of how the

doctor's stimulating and encouraging presence always flooded the

darkest sick-rooms with light, and then added, `You are doing

the same good work in the same way, with a vastly enlarged

sphere of "practice." As one of your grateful patients I send

you my hearty thanks.' But the praise she treasured most was

contained in a letter she opened one morning in the middle of

the summer:

DEAR FRIEND:

I must thank thee for thy admirable

book `Deephaven.' I have given several copies to friends, all of

whom appreciate it highly, and I have just been reading it over

for the third time. I know of nothing better in our

literature of the kind, though it recalls Miss Mitford's `Our

Village' and `The Chronicles of Carlingford.' I heartily

congratulate thee on thy complete success and am

Very

truly thy friend

John

Greenleaf Whittier

Mr. Whittier! She had enjoyed what he had written so much ever since she was a child that she was overcome to know that anything she was able to do could please him! She grew more and more astonished as further compliments poured in upon her, and was pleased -- in a way -- and yet she confessed to Professor Parsons that she found it very hard to realize that all this praise belonged to her, and it all seemed very vague when she tried to take it in. She was almost a little sorrowful when she thought how she used to build castles in Spain about this very thing, and now that she found the castles in finer array than she had ever dreamed, she didn't seem to care so very much for them after all. She begged him not to think she was ungrateful, but the pleasure somehow was such a different pleasure. .... She was very used up and lazy all that summer and had strained her shoulder fairly badly swimming at Wells. But beneath every thought surged the warm glow that even if her book didn't half say the things she had tried, and didn't have any real `finish,' at least she had made a beginning. She had done something of which her friends and family were proud. Next year...

In the next year she wrote hastily to Professor Parsons:

My dear father died suddenly yesterday

at the mountains. It is an awful blow to me. I know you will ask

God to help me bear it. I don't know how I can live without him.

It is so hard for us.

Yours lovingly

SARAH

from a tintype

III.

Contents

[']DEAR MISS JEWETT: Don't be too proud, now your book has succeeded so splendidly, to send some stories and sketches to your old friend, the "Atlantic Monthly."' That had been Mr. Howells' jocular tribute to `Deephaven.' At twenty-eight Sarah Jewett was considered an important asset to the journal which had established itself as the focal point in American literature. It is difficult to-day perhaps to realize the full height of this distinction. But one look at the neighbors that `Mr. Bruce' and `The Shore House' found in the magazine reveals how fully the early `Atlantic' had achieved its purpose. Miss Jewett's first story was printed in the lean years following the Civil War. Thoreau and Hawthorne had just died. Emerson had written his `Terminus' in 1867. The other poetic talents which had been enlisted at the magazine's foundation in the previous decade now seemed exhausted, and had turned to translation. Longfellow, Norton, and T. W. Parsons were all occupied with their versions of Dante during the half-dozen years after the war, and Bayard Taylor's `Faust' appeared, as did also Cranch's 'Virgil' and Bryant's `Homer.' Consequently the `Atlantic' could show nothing more than stories by John Hay and Edward Everett Hale, a poem by Taylor, and Howells' reviews of the elder Henry James' `Secret of Swedenborg,' Mark Twain's `Innocents Abroad,' and Whittier's `Ballads of New England.'

But four years later it was once more in full swing, and `The Shore House' was accompanied, among others, by Longfellow's `Rhyme of Sir Christopher,' Holmes' Phi Beta Kappa `Poem Served to Order,' a lyric by Aldrich, N. S. Shaler's `Summer Journey of a Naturalist,' and a substantial chronicle of `Contemporary European Art.' Even this list, however, does not begin to convey what an event the appearance of an `Atlantic' could be. The issue of May, 1875, which contained Sarah Jewett's third accepted contribution, her poem `Together,' shows the `Atlantic' at its typical best. Marshalled together there were Longfellow's 'Amalfi,' Chapter V of 'Roderick Hudson' by H. James, Jr., poems by Lowell and Aldrich, an essay by Howells, the fifth section of Mark Twain's `Old Times on the Mississippi,' Whittier's `Lexington,' and Celia Thaxter's account of the Memorable Murder at Smutty Nose.

It was in no sense sectional. It attracted to itself a good share of that new realism of `local color' which was the chief contribution of the seventies to American literature. It not only furnished a cradle for the early efforts of Howells and James, but explored the Mississippi with Mark Twain, and when `The Luck of Roaring Camp' swept the country in the then almost unheard of `Overland Monthly,' James T. Fieldsimmediately wrote Bret Harte a flattering request for further stories like it. Other regions of the country were finding their recorders, and although the recently founded `Scribner's' introduced in 1873 `Sieur George,' the first of Cable's pictures of old creole days in New Orleans, and Page's `Marse Chan' a decade later, still the `Atlantic' brought the Tennessee mountains to general attention with Craddock's `The Dancin' Party at Harrison's Cove' in 1878. In fact the `Atlantic' in its young prime seemed to be aware of the value of every one, except the two greatest. Walt Whitman had contributed two poems in its opening decade, but you look in vain for any mention of him during Howells' editorship, while Aldrich thought him little better than a charlatan. Herman Melville, disheartened by his apathetic country, had long since disappeared in the gloomy silence that engulfed his last thirty years.

Sarah Jewett, drawing pictures of what she knew, discovered that people in California and Virginia were doing a similar thing, and that their efforts were springing at once into widespread popularity. America seemed with the expansion of its lands to be suddenly aware of its sectional differences, and eager to taste the distinctive flavor of each. The protecting fences might all be broken down by the onrushing crowd, but before their feet had trampled every region to a level of standardization a few writers caught the essence of the old provincial charm.

Miss Jewett thus found her niche

virtually carved for her. All she had to do was to step

gracefully into it. Boston certainly raised no question about

considering her a fully arrived celebrity after the appearance

of `Deephaven,' for she was among the distinguished guests

invited to Oliver Wendell Holmes' seventieth birthday party. And

fortunately the impression did not stop with Boston. John

Burroughs, who had already produced his early appreciation of

Walt Whitman and followed it with `Wake-Robin' and others in his

long series of nature studies, had met her at that party and

wrote to her a few years later:

'MY DEAR MISS JEWETT: I was glad to

see your signature at the end of a letter expressing

appreciation of my books. I know you are a genuine country woman,

and when you take a bite of a book that treats of country

things, you know quick enough whether the flavor be true or

false. I remember your face at the Holmes breakfast, where I saw

so many faces that I have forgotten .... I remember also your

first sketches in the "Atlantic" and the clear human impression

which they made upon me -- an impression which your later works

deepen and fill out. I should not have allowed you to get ahead

of me in the matter of thanks: my thanks are due to you also,

and my good wishes for your future are from the heart. Now I

know you are from Maine I can taste the flavor of the birch in

your books. May the birches be kind to you.'

That was the real thing. The country woman, no matter how fully Boston took her to its heart, never wanted to be anything else. Her stories caught the flavor not only of the birches, but of the salt marshes, the roadside chicory and Queen Anne's lace. But there was nothing untutored about her. She might tell Horace Scudder that she had never studied in her life, but the books that lined the mellow shelves of her library had bestowed upon her a culture as rich and spacious as her house itself. She was forever reading `Vanity Fair' and declaring it `a very great book, and for its time Tolstoy and Zola and Daudet and Howells and Mark Twain and Turgenieff and Miss Thackeray of this day all rolled into one, so wise and great it is and reproachful and realistic and full of splendid scorn for meanness and wickedness, which scorn the Zola school seems to lack.' Her enthusiasms were finely catholic. She loved the seventeenth century, and read Donne and Vaughan and Sir Thomas Browne with the greatest delight. She had an affection for Dr. Johnson, and once wrote a poem about Emerson. Dana's `Two Years Before the Mast' called out her repeated admiration, and she said that it seemed as much a classic as anything America had to give. She saw one day a set of Voltaire included in an auction, and was tempted to bid, but didn't quite dare propose to her mother the bringing in of ninety-seven new volumes at one fell swoop. She declared to Mrs. Fields that there was no more charming book in the world than Dorothy Wordsworth's `Tour in Scotland,' and added, `It is just our book, and the way we enjoy things, isn't it, when we are footing it out of doors?'

What she read now often threw flashes of light on the problem of her own writing. When she picked up `The Pearl of Orr's Island' for the first time in years, the beginning struck her as just as clear and strong as the day she had read it as a child. She would never forget the reality of delight she had found in its pungent flavor. But now she reflected, `Alas, that she couldn't finish it in the same noble key of simplicity and harmony; but a poor writer is at the mercy of much unconscious opposition. You must throw everything and everybody aside at times, but a woman made like Mrs. Stowe cannot bring herself to that cold selfishness of the moment for one's work's sake, and the recompense for her loss is a divine touch here and there in an incomplete piece of work.'

At first she had been only half-hearted about `Anna Karénina,' but suddenly something in Tolstoy's short stories caught her, some indefinable kinship of spirit that kept her awake until almost morning, made her drowse in church and write hurriedly afterwards: `I never felt the soul of Tolstoy's work until last night . . . but now I know what he means, and I know that I can dare to keep at the work I sometimes have despaired about because you see people are always caught by fringes of it, and liked the stories if they liked them at all for some secondary quality. I know there is something true, and yet I myself have often looked only at the accidental and temporary part of them.'

Perhaps the greatest single spur to her work was Flaubert. She believed that he alone was sufficient refutation to the people who objected to the new realism because it dwelt on commonplaces and trivialities. For he gave every detail weight, and made her feel that the woes of Hamlet did not absorb her thoughts any more than `the silly wavering gait of Madame Bovary,' who was `uninteresting, ill-bred, and without any of the attraction of rural surroundings.' She herself sought a kindred skill in writing about the simple country people. From the day she discovered them she kept a slip of paper pinned on her secretary in the upper hall, inscribed with two of Flaubert's sentences: `Écrire la vie ordinaire comme on écrit l'histoire,' and, `C'est ne pas de faire rire, ni de faire pleurer, ni de vous mettre à fureur, mais d'agir à la façon de la nature, c'est à dire de faire rêver.' There they remained, behind the small copy of the Raeburn portrait of Scott and the engraving of Michel de Montaigne and the Venetian lion, behind the pen tray and the silver candlesticks in which the candles were usually burnt low; and they caught her eye whenever she sat down to write.

As she recovered her emotional balance after her first deep sadness, she wrote again to Professor Parsons: `I think that was the reason people liked "Deephaven" -- it was a book written by a girl, which is perhaps a rarer thing than seems possible at first thought. I am beginning to like it myself in a curious sort of way, for I am not the one who wrote it any longer and in this last year since my father's death, though I have learned many new things, I have outgrown a good deal else.' She published her children's stories as a book, and put into a volume called `Old Friends and New' some new sketches she had been doing, along with `Mr. Bruce' and other old ones that had not fitted into `Deephaven.' Two years later she had another collection ready and wrote the dedication:

TO

T. H. J.

My dear father;

my dear friend;

The best and wisest man I ever knew;

Who taught me many lessons and showed me many

things

As we went together along the

Country-By-Ways.

But she had not been at all well. The doctor forbade her any reading or writing for a whole winter, and when she could work, she often felt an empty lack of satisfaction in the results.

She was fortunate in having her close intimacy with Mrs. Fields ripen about this time. James T. Fields, the most notable publisher and editor in America, died in 1881. He had married in early middle life the beautiful Annie Adams, not yet twenty, and had taken his bride on a long trip abroad. They had visited the Tennysons, and stayed some time with the Brownings at Florence, and young Mrs. Fields had had the even more remarkable experience of meeting Leigh Hunt the month before his death, and hearing the very words of a conversation of Shelley's. She wrote thrilled accounts of all these things into her journals, those rich stores that were to yield, after her husband's death, her volumes of reminiscence, `Authors and Friends,' and `A Shelf of Old Books.' Under the sway of this keen, vigorous publisher and his exquisite wife their decorous Georgian house at 148 Charles Street was from the start `addicted to every hospitality and every benevolence,' As Henry James said, `addicted to the cultivation of talk and wit and to the ingenious multiplication of such ties as could link the upper half of the title page with the lower.' It became the natural meeting place for every one of literary and dramatic distinction on both sides of the water, and an abundant treasury of associations. It was the nearest approach ever made to an American salon.