Main Contents & Search

Betty Leicester: A Story for Girls, 1890

Chapters 13-17

CONTENTS

XIII. A GREAT EXCITEMENT

XIV. THE OUT-OF-DOOR CLUB

XV. THE STARLIGHT COMES IN

XVI. DOWN THE RIVER

XVII. GOING AWAY

Beatrice Stevens

See first note for Chapter 1.

XIII.

A GREAT EXCITEMENT.

That afternoon Betty's lively young voice grew droning and dull after a while, as she read the life of Dr. Donne, and at last she stopped altogether.

"Aunt Mary, I can't help thinking about seeing the Fosters' father. Do you suppose he will come home and frighten them some night?"

"No, he would hardly dare to come where they are sure to be looking for him," said Aunt Mary. "Dear me, the thought makes me so nervous."

"When I have read to the end of this page I will just run down to see Nelly a few minutes, if you can spare me. I keep dreading to see her until I am almost afraid to go."

Miss Mary sighed and said yes. Somehow she didn't get hold of Betty's love, -- only her duty.

Betty lingered in the garden and picked some mignonette before she started, and a bright carnation or two from Aunt Barbara's special plants. The Fosters' house was farther down the street on the same side, and Nelly's blinds were shut, but if Betty had only known it, poor Nelly was looking out wistfully through them, and wishing with all her heart that her young neighbor would come in. She dreaded the meeting, too, but there was such a simple, frank friendliness about Betty Leicester that it did not hurt as if one of the other girls had come.

There came the sound of the gate-latch, and Nelly went eagerly down. "Come up to my room; I was sitting there sewing," she said, blushing very red, and Betty felt her own cheeks burn. How dreadful it must be not to have such a comforting dear father as hers! She put her arms round Nelly's neck and kissed her, and Nelly could hardly keep from crying; but up-stairs they went to the bedroom, where Betty had never happened to go before. She felt suddenly, as she never had before, how pinched and poor the Fosters must be. Nelly was determined to be brave and cheerful, and took up her sewing again. It happened to be a little waist of Betty's own. Betty tried to talk gayly about being very tired of reading "Walton 's Lives." She had come to a dull place in Dr. Donne's memoirs, though she thought them delightful at first. She was just reading "The Village on the Cliff," on her own account, with perfect delight.

"Harry reads 'Walton's Angler,'" said Nelly. "That's the same man, isn't he? It is a stupid-looking old brown book that belonged to my grandfather."

"Papa reads it, too," said Betty, nodding her head wisely. "I am in such a hurry to have him come, when I think of Harry. I am sure that he will help him to be a naturalist or something like that. Mr. Buckland would have just loved Harry. I knew him when I was a little bit of a thing. Papa used to take me to see him in London, and all his dreadful beasts and snakes used to frighten me, but I do so like to remember him now. Harry makes me think of Robinson Crusoe and Mayne Reid's books, and those story-book boys who used to do such wild things fishing and hunting."

"We used to think that Harry never would get on because he spent so much time in the woods, but somehow he always learned his lessons too," said Nelly proudly; "and now his fishing brings in so much money that I don't know how we shall live when winter comes. We are so anxious about winter. Oh, Betty, it is easy to tell you, but I can't bear to have other people even look at me;" and she burst into tears and hid her face in her hands.

"Let us go out-doors, just down through the garden and across into the woods a little while," pleaded Betty. "Do, Nelly, dear!" and presently they were on their way. The fresh summer air and the sunshine were much better than the close-shaded room, where Nelly was startled by every sound about the house, and they soon lost their first feeling of constraint as they sat under a pine-tree whipping two of Miss Barbara Leicester's new tea napkins. Betty had many things to say about her English life and her friends. Mary Beck never cared to hear much about England, and it was always delightful to have an interested listener. At last the sewing was finished, and Nelly proposed that they should go a little way farther, and come out on the river bank.

Harry would be coming up about this time with his fare of fish, if he had had good luck. It would be fun to shout to him as he went by.

They pushed on together through the open pasture, where the sweet-fern and bayberry bushes grew tall and thick; there was another strip of woods between them and the river, and just this side was a deserted house, which had not been lived in for many years and was gray and crumbling. The fields that belonged to it had been made part of a great sheep pasture, and two or three sheep were standing by the half-opened door, as if they were quite at home there in windy or wet weather. Betty had seen the old house before, and thought it was most picturesque. She now proposed that they should have a picnic party by and by, and make a fire in the old fireplace; but Nelly Foster thought there would be great danger of burning the house down.

"Suppose we go and look in?" pleaded Betty. "Mary Beck and I saw it not long after I came, but she thought it was going to rain, so that we didn't stop. I like to go into an empty old ruin, and make up stories about it, and wonder who used to live there. Don't stop to pick these blackberries; you know they aren't half ripe," she teased Nelly; and so they went over to the old house, frightening away the sheep as they crossed the doorstep boldly. It was all in ruins; the roof was broken about the chimney, so that the sun shone through upon the floor, and the light-red bricks were softened and sifting down. In one corner there was a heap of withes for mending fences, which had been pulled about by the sheep, and there were some mud nests of swallows high against the walls, but the birds seemed to have already left them. This room had been the kitchen, and behind it was a dark, small place which must have been a bedroom when people lived there, dismal as it looked now.

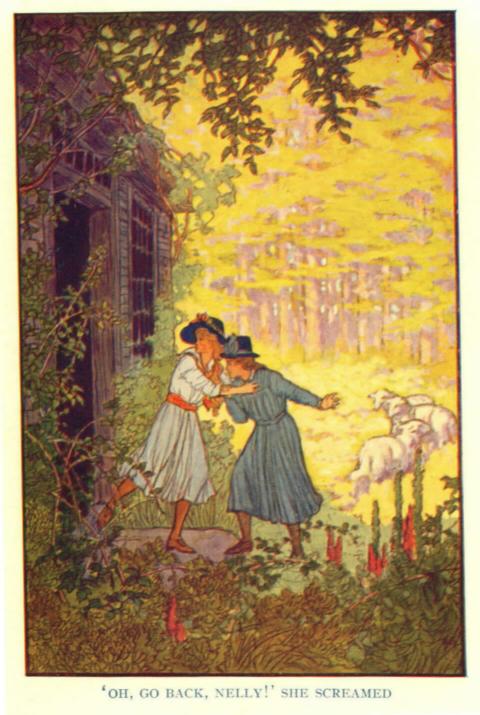

"I am going to look in here and all about the place," said Betty cheerfully, and stepped in to see what she could find.

"Oh, go back, Nelly!" she screamed, in a great fright, the next moment; and they fled out of the house into the warm sunshine. They had had time to see that a man was lying on the floor as if he were dead. Betty's heart was beating so that she could hardly speak.

"We must get somebody to come," she panted, trying to stop Nelly. "Was it somebody dead?"

But Nelly sank down as pale as ashes into the sweet-fern bushes, and looked at her strangely. "Oh, Betty Leicester, it will kill mother, it will kill her! I believe it was my father; what shall I do?"

"Your father," faltered Betty, -- "your father? We must go and tell." Then she remembered that he was a hunted man, a fugitive from justice.

They looked fearfully at the house; the sheep had come back and stood again near the doorway. There was something more horrible than the two girls had ever known in the silence of the place. It would have been less awful if there had been a face at the broken door or windows.

"Henry -- we must try to stop Henry," said poor pale Nelly, and they hurried toward the river shore. They could not help looking anxiously behind them as they passed the belt of pine; a terrible fear possessed them as they ran. "He is afraid that somebody will see him. I wonder if he will come home to-night."

"He must be ill there," said Betty, but she did not dare to say anything else. What an unendurable thing to be afraid and ashamed of one's own father!

They looked down the river with eager eyes. Yes, there was Harry Foster's boat coming up slowly, with the three-cornered sail spread to catch the light breeze. Nelly gave a long sigh and sank down on the turf, and covered her face as she cried bitterly. Betty thought, with cowardly longing, of the quiet and safety of Aunt Mary's room, and the brown-covered volume of "Walton's Lives." Then she summoned all her courage. These two might never have sorer need of a friend than in this summer afternoon.

Beatrice Stevens

Henry Foster's boat sailed but slowly. It was heavily laden, and the wind was so light that from time to time he urged it with the oars. He did not see the two girls waiting on the bank until he was close to them, for the sun was in his eyes and his thoughts were busy. His father's escape from jail was worse than any sorrow yet; nobody knew what might come of it. Harry felt very old and careworn for a boy of seventeen. He had determined to go to see Miss Barbara Leicester that evening, and to talk over his troubles with her. He had been able to save a little money, and he feared that it might be demanded. He had already paid off the smaller debts that were owed in the village; but he knew his father too well not to be afraid of getting some menacing letters presently. If his father had only fled the country! But how could that be done without money? He would not work his passage; Harry was certain enough of that. Would it not be better to let him have the money and go to the farthest limit to which it could carry him?

Something made the young man shade his eyes with his hand and took toward the shore; then he took the oars and pulled quickly in. That was surely his sister Nelly, and the girl beside her, who wore a grayish dress with a white blouse waist, was Betty Leicester. It was just like kind-hearted little Betty to have teased poor Nelly out into the woods. He would carry them home in his boat; he could rub it clean with some handfuls of hemlock twigs or river grass. Then he saw how strangely they looked, as he pushed the boat in and pulled it far ashore. What in the world had happened?

Nelly tried to speak again and again, but her voice could not make itself heard. "Oh, don't cry any more, Nelly, dear," said Betty, trembling from head to foot, and very pale. "We went into the old house up there by the pasture, and found -- Nelly said it was your father, and we thought he was very ill."

"I'll take you both home, then," said Harry Foster, speaking quickly and with a hard voice. "Get in, both of you,-this is the shortest way, -- then I'll come back by my self."

"Oh, no, no!" sobbed Nelly. "He looked as if he were dying, Harry; he was lying on the floor. We will go, too; he couldn't hurt us, could he?" And the three turned back into the woods. Betty's heart almost failed her. She felt like a soldier going into battle. Oh, could she muster bravery enough to go into that house again? Yet she loved her father so much that doing this for another girl's father was a great comfort, in all her fear.

The young man hurried ahead when they came near the house, and it was only a few minutes before he reappeared.

"You must go and tell mother to come

as quick as she can, and hurry to find the doctor and tell him;

he will know what to do. Father has been dreadfully hurt

somehow. Perhaps Miss Leicester will let Jonathan come to help

us get him home." Harry Foster's face looked old and strange; he

never would seem like a boy any more, Betty thought, with a

heart full of sympathy. She hurried away with Nelly; they could

not bring help fast enough.

After the great excitement was over, Betty felt very tired and unhappy. That night she could be comforted only by Aunt Barbara's taking her into her own bed, and being more affectionate and sympathetic than ever before' even talking late, like a girl, about the Out-of-Door Club plans. In spite of this attempt to return to every-day thoughts, Betty waked next morning to much annoyance and trouble. She felt as if the sad affairs of yesterday related only to the poor Fosters and herself, but as she went down the street, early, she was stopped and questioned by eager groups of people who were trying to find out something more about the discovery of Mr. Foster in the old house. It proved that he had leaped from a high window, hurting himself badly by the fall, when he made his escape from prison, and that he had been wandering in the woods for days. The officers had come at once, and there was a group of men outside the Fosters' house. This had a terrible look to Betty. Everybody said that the doctor believed there was only a slight chance for Mr. Foster's life, and that they were not going to try to take him back to jail. He had been delirious all night. One or two kindly disposed persons said that they pitied his poor family more than ever, but most of the neighbors insisted that "it served Foster just right." Betty did her errand as quickly as possible, and hastily brushed by some curious friends who tried to detain her. She felt as if it were unkind and disloyal to speak of her neighbor's trouble to everybody, and the excitement and public concern of the little village astonished her very much. She did not know, until then, how the joy or trouble of one home could affect the town as if it were one household. Everybody spoke very kindly to her, and most people called her "Betty," and seemed to know her very well, whether they had ever spoken to her before or not. The women were standing at their front doors or their gates, to hear whatever could be told, and our friend looked down the long street and felt that it was like running the gauntlet to get home again. Just then she met the doctor, looking gray and troubled, as if he had been awake all night, but when he saw Betty his face brightened.

"Well done, my little lady," he said, in cheerful voice, which made her feel steady again, and then he put his hand on Betty's shoulder and looked at her very kindly.

"Oh, doctor! may I walk along with you little way?" she faltered. "Everybody asks me to tell" -

"Yes, yes, I know all about it," said the doctor; and he turned and took Betty's hand as if she were a child, and they walked away together. It was well known in Tideshead that Dr. Prince did not like to be questioned about his patients.

"I was wondering whether I ought to go to see Nelly," said Betty, as they came near the house. "I haven't seen her since I came home with her yesterday. I -- didn't quite dare to go in as I came by."

"Wait until to-morrow, perhaps," said the doctor. "The poor man will be gone then, and you will be a greater comfort. Go over through the garden. You can climb the fences, I dare say," and he looked at Betty with a queer little smile. Perhaps he had seen her sometimes crossing the fields with Mary Beck.

"Do you mean that he is going to die today?" asked Betty, with great awe. "Ought I to go then?"

"Love may go where common kindness is shut out," said Dr. Prince. "You have done a great deal to make those poor children happy, this summer. They had been treated in a very narrow-minded way. It was not like Tideshead, I must say," he added, "but people are shy sometimes, and Mrs. Foster herself could not bear to see the pity in her neighbors' faces. It will be easier for her now."

"I keep thinking, what if it were my own papa?" said Betty softly. "He couldn't be so wicked, but he might be ill, and I not there."

"Dear me, no!" said the doctor heartily, and giving Betty's hand a tight grasp and a little swing to and fro. "I suppose he's having a capital good time up among his glaciers. I wish that I were with him for a month's holiday;" and at this Betty was quite cheerful again.

Now they stopped at Betty's own gate. "You must take your Aunt Mary in hand a little, before you go away. There's nothing serious the matter now, only lack of exercise and thinking too much about herself."

"She did come to my tea-party in the garden," responded Betty, with a faint smile, "and I think sometimes she almost gets enough courage to go to walk. She didn't sleep at all last night, Serena said this morning."

"You see, she doesn't need sleep," explained Dr. Prince, quite professionally. "We are all made to run about the world and to work. Your aunt is always making blood and muscle with such a good appetite, and then she never uses them, and nature is clever at revenges. Let her hunt the fields, as you do, and she would sleep like a top. I call it a disease of too-wellness, and I only know how to doctor sick people. Now there's a lesson for you to reflect upon," and the busy doctor went hurrying back to where he had left his horse standing, when he first caught sight of Betty's white and anxious face.

As she entered the house Aunt Barbara was just coming out. "I am going to see poor Mrs. Foster, my dear, or to ask for her at the door," she said, and Serena and Letty and Jonathan all came forward to ask whether Betty knew any later news. Seth Pond had been loitering up the street most of the morning, with feelings of great excitement, but he presently came back with instructions from Aunt Barbara to weed the long box-borders behind the house, which he somewhat unwillingly obeyed.

A few days later the excitement was at an end, the sad funeral was over, and on Sunday the Fosters were at church in their appealing black clothes. Everybody had been as kind as they knew how to be, but there were no faces so welcome to the sad family as our little Betty's and the doctor's.

"It comes of simply following her instinct to be kind and do right," said the doctor to Aunt Barbara, next day. "The child doesn't think twice about it, as most of us do. We Tideshead people are terribly afraid of one another, and have to go through just so much before we can take the next step. There's no way to get right things done but to simply do them. But it isn't so much what your Betty does as what she is."

"She has grown into my old heart," said Aunt Barbara. "I cannot bear to think of her going away and taking the sunshine with her! -- and yet she has her faults, of course," added the sensible old lady.

"Oh, by the way!" said Dr. Prince, turning back. "My wife told me to ask you to come over to tea to-night and bring the little girl; I nearly forgot to give the message."

"I shall be very happy to come," answered Miss Leicester, and the doctor nodded and went his busy way. Betty was very fond of going to drive with him, and he looked about the neighborhood as he drove along, hoping to catch sight of her; but Betty was at that moment deeply engaged in helping Letty shell some peas for dinner, at the other side of the house, in the garden doorway of the kitchen. She had spent an hour before that with Mrs. Beck, while they tried together with more or less success to trim a new sailor hat for Mary Beck like one of Betty's own. Mrs. Beck was as friendly as possible in these days, but whenever the Fosters were mentioned her face grew dark. She did not like Mrs. Foster; she did not exactly blame her for all that had happened, but she did not pity her either, or feel a true compassion for such a troubled neighbor. Betty never could understand it. At any rate, she had been saved by her unsettled life from taking a great interest in her own or other people's dislikes.

That evening, just as the tea-party was in full progress, somebody came for Dr. Prince; and when he returned from his study he announced that he must go at once down the river road to see one of his patients who was worse. Perhaps he saw an eager look in Betty's eyes, for he asked gravely if Miss Leicester had a niece to lend, it being a moonlight evening and not too long a drive. Aunt Barbara made no objection, and our friend went skipping off to the doctor's stable in high glee.

"Oh, that's nice!" she exclaimed. "I'm so glad that you're going to take Pepper; she's such a dear little horse."

"Pepper is getting old," said the doctor, "but she really likes to go out in the evening. You can see how fast she will scurry home. Get me a whip from the rack, will you, child? I am anxious to be off."

Mrs. Prince and Aunt Barbara were busy talking in the parlor, and were taking great pleasure in their social occasion, but Betty was so glad that she need not stay to listen, instead of going down the town street and out among the quiet farms behind brisk old Pepper. The wise, kind doctor at her side was silent as he thought about his patient, yet he felt much pleasure in Betty's companionship. They could smell the new marsh hay and hear the trees-toads, it was a most beautiful summer night. Betty felt very grateful and happy, she did not exactly know why; it was not altogether the effect of Mrs. Prince's tea and cakes, or even because she was driving with the doctor, but the restlessness and uncertainty that make so great a part of a girl's life seemed to have gone away out of her heart. Instead of the excitement there was a pleasant quietness and sense of security, no matter what might be going to happen.

Presently the doctor appeared to have thought enough about his patient. "You don't feel chilly, do you?'' be asked kindly. "I find it damp and cold, sometimes, after a hot day, crossing this low land."

"Oh, no, I'm as warm as toast," answered Betty. "Whom see you going to see, Dr. Prince? Old Mr. Duff?"

"No, he is out-of-doors again. I saw him in the hayfield this morning. You haven't been keeping up with my practice as well as usual, of late," said the doctor, laughing a little. "I am going to see a girl about your own age. I am afraid that I am going to lose her, too."

"Is it that pretty Lizzie Edwards who sits behind the Becks' pew? I heard that she had a fever. I saw her the last Sunday that she was at church." Betty's heart was filled with dismay, and the doctor did not speak again. They were near the house now, and could see some lights flitting about; and as they stopped the sick girl's father stole silently from behind the bushes and began to fasten the horse, so that Dr. Prince could go in directly. Betty could hear the ominous word "sinking," as they whispered together; then she was left alone. It seemed so sad that this other girl should be near the door of death, and so close to the great change that must come to every one. Betty had never known so direct a consciousness of the inevitableness of death, but she was full of life herself, and so eager and ready for whatever might be coming. What if this other girl had felt so, too? She watched the upper windows where the dim light shone, and now and then a shadow crossed the curtain. Everything out-of-doors was quiet and sweet; the moon went higher and higher, and the wind rustled among the apple-trees. Some white petunias in a little plot near by looked strangely white, and Betty thought that perhaps the other girl had planted them, and there they were growing on. Now she was going to die. Betty wondered what it would be like, and if the other girl knew, and if she minded so very much. After a few minutes she found herself saying an eager prayer that the doctor might still cure her, and keep her alive. If she must die, Betty hoped that she herself might do some of the things that Lizzie Edwards would have done, and take her place. When old people had to go, who had done all they wished to do, and got tired, and could not help thinking about having a new life, that was one thing; but to go now and leave all your hopes and plans behind, -- indeed, it seemed too hard. But Betty had a sense of the difference between what things could be helped and what were in God's hands, and when she had said her prayer she waited again hopefully for a long time in the moonlight.

At last there seemed to be more movement in the house and she could hear voices; then she heard somebody sobbing, and the light in the upper room went quickly out.

The doctor came after a few minutes more, which seemed very long and miserable. Pepper had fallen asleep, good old horse! and Betty did not dare to ask any questions.

"Well, well," said the doctor, in a surprisingly cheerful voice, "I forgot all about you, Miss Betty Leicester. I hope that you're not cold this time, and I don't know what the aunts will have to say about us; it is nearly eleven o'clock."

"I'm not cold, but I did get frightened," acknowledged Betty faintly; then she felt surprisingly light-hearted. Dr. Prince could not be in such good spirits if he had just seen his poor young patient die!

"We got here just in time," he said, tucking the light blanket closer about Betty. "We've pulled the child through, but she was almost gone when I first saw her; there was just a spark of life left, -- a spark of life," repeated the doctor.

"Who was it crying?" Betty asked.

"The mother," said the doctor. "I had just told her that she was going to keep the little girl. Why, here's a good sound sassafras lozenge in my pocket. Now we'll have a handsome entertainment."

Betty, who had just felt as if she were going to cry for nobody knew how long, began to laugh instead, as Dr. Prince broke his unexpected lozenge into honest halves and presented her solemnly with one of them. There was never such a good sassafras lozenge before or since, and Pepper trotted steadily home to her stall and the last end of her supper. "Only think, if the doctor hadn't known just what to do," said Betty later to Aunt Barbara, "and how he goes all the time to people's houses! Every day we see him going by to do things to help people. This might have been a freezing, blowing might, and he would have gone just the same."

"Dear child, run up to your bed now," said Aunt Barbara, kissing her good-night; for Betty was very wide awake, and still had so many things to say. She never would forget that drive at night. She had been taught a great lesson of the good doctor's helpfulness, but Aunt Barbara had learned it long ago.

The young man shaded his eyes with his hand and looked toward

the shore.

from "A Bit of Color," the serialization of an early version

of Betty Leicester in St. Nicholas; see note

at the end of Chapter 1 for details.

NOTES FOR CHAPTER XIII. A GREAT EXCITEMENT

life of Dr. Donne:Probably

Betty is reading from Isaak Walton's Lives (1670). A

life of the English poet John Donne (1572-1631) is the first of

the biographies in this collection.

[ Back ]

mignonette: a garden annual

with yellow-green blossoms, R. odorata.

[ Back ]

"The Village on the Cliff": The

Village on the Cliff (1866) is by Ann Thackeray, Lady

Ritchie.

[ Back ]

'Walton's Angler': The

Compleat Angler (1653-5) by Izaak Walton.

[ Back ]

Robinson Crusoe ... Mayne Reid's books: Daniel Defoe

(1660-1731) published his novel, Robinson Crusoe in

1719. Thomas Mayne Reid (1818-1883) was a prolific writer of

books for children and adults. Irish born, he emigrated to the

United States, where he served in the Mexican War, upon which a

number of his books were based. The Rifle Rangers (1850)

established him as a writer for adults; The Boy Hunters

(1853) is one of his notable juvenile titles.

[ Back ]

whipping: Probably they are

sewing seams around the edges of the napkins.

[ Back ]

Beatrice Stevens

XIV.

THE OUT-OF-DOOR CLUB.

The Out-of-Door Club in Tideshead was slow in getting under way, but it was a great success at last. Its first expedition was to the Picknell farm, to see the place where there had been a great battle with the French and Indians, in old times, and the relics of a beaver-dam were to be inspected beside. Mr. Picknell came to talk about the plan with Miss Barbara Leicester, who was going to drive out to the farm in the afternoon, and then walk back with the club, as besought by Betty. She was highly pleased with the eagerness of her young neighbors, who had discovered in her an unsuspected sympathy and good-fellowship at the time of Betty's June tea-party. It had been a pity to make believe old in all these late years, and to become more and more a stranger to the young people. Perhaps, if the club proved a success, it would be a good thing to have winter meetings too, and read together.

Somehow Miss Barbara had never before known exactly what to do for the young folks. She could have a little supper for them in the evening, and ask them to come and read with her; or perhaps she might propose to read some good story to them, and some poetry. They ought to know something of the great poets. Miss Mary Leicester was taken up with the important business of her own invalidism, but it might be a very good thing for her to take some part in such pleasant plans. Under all Aunt Barbara's shyness and habit of formality Betty had discovered her warm and generous heart. They had become fast friends, and, to tell the truth, Aunt Mary was beginning to have an uneasy and wistful consciousness that she was causing herself to be left out of many pleasures.

The gloom and general concern at the

time of the Fosters' sorrow had caused the first club meeting to

be postponed until early in August; and then, though August

weather would not seem so good for out-of-door expeditions, this

one Wednesday dawned like a cool, clear June day, and at three

o'clock the fresh easterly wind had not ceased to blow and yet

had not brought in any seaward clouds. There were eleven boys

and girls, and Miss Barbara Leicester made twelve, while with

the two Picknells the club counted fourteen. The Fosters

promised to come later in the summer, but they did not feel in

the least hurt because some of their friends urged them to join

in cheerful company this very day. It seemed to Betty as if

Nelly looked brighter and somehow unafraid, now that the first

miserable weeks had gone. It may have been that poor Nelly was

lighter-hearted already than she often had been in her father's

lifetime.

They dared the club to cross a wide brook on insecure

stepping-stones.

Beatrice Stevens

Betty and Mary Beck walked together, at first; but George Max asked Mary to walk with him, so they parted. Betty liked Harry Foster better than any other of the boys, and really missed him to-day. She was brimful of plans about persuading her father to help Harry to study natural history. While the club was getting ready to walk two by two, Betty suddenly remembered that she was an odd one, and hastily took her place between the Grants, insisting that they three must lead the procession. The timid Grants were full of fun that day, for a wonder, and a merry head to the procession they were with Betty, walking fast and walking slowly, and leading the way by short cuts across-country with great spirit. They called a halt to pick huckleberries, and they dared the club to cross a wide brook on insecure stepping-stones. Everybody made fun for everybody else whenever they saw an opportunity, and when they reached the Picknell farm, quite warm and excited, they were announced politely by George Max as "the Out-of-Breath Club." The shy Picknells wore their best white Sunday dresses, and the long white farm-house with its gambrel roof seemed a delightfully shady place as the club sat still a while to cool and rest itself and drink some lemonade. Mrs. Picknell was a thin, bright-eyed little woman, who had the reputation of being the best housekeeper in town. She was particularly kind to Betty Leicester, who was after all no more a stranger to her than were some of the others who came. It was lovely to see that Mrs. Picknell and Julia were so proud of Mary's gift for drawing, and evidently managed that she should have time for it. Mary had begun to go to Riverport every week for a lesson.

"She heard that Mr. Clinturn, the famous artist, was spending the summer there, and started out by herself one day to ask him to give her lessons," Mrs. Picknell told Betty proudly. "He said at first that he couldn't spare the time; but I had asked Mary to take two or three of her sketches with her, and when he saw them he said that it would be a pleasure to help her all that he could."

"I do think this picture of the old packet-boat coming up the river is the prettiest of all. Oh, here's Aunt Barbara; do come and see this, Aunty!"said Betty, with great enthusiasm. "It makes me think of the afternoon I came to you."

Miss Leicester took out her eyeglasses and looked as she was bidden. "It is a charming little water-color," she said, with delighted surprise. "Did you really teach yourself until this summer?"

"I only had my play paint-box until last winter," said Mary Picknell. "I am so glad you like it, Miss Leicester;" for Miss Leicester had many really beautiful pictures of her own, and her praise was worth having.

Then Mr. Picknell took his stick from behind the door, and led the company of guests out across the fields to a sloping rough piece of pasture land, with a noisy brook at the bottom, where a terrible battle had been fought in the old French and Indian war. He read them an account of it from Mr. Parkman's history, and told all the neighborhood traditions of the frightened settlers, and burnt houses, and murdered children and very old people, and the terrible march of a few captives through the winter woods to Canada. How his own great-great grandfather and grandmother were driven away from home, and each believed the other dead for three years, until the man escaped, and then went, hearing that his wife was alive, to buy her freedom. They came to the farm again, and were buried in the old burying-lot, side by side.

"There was a part of the story which you left out," Mrs. Picknell said "When they killed the little baby, the Indians told its poor mother not to cry about it or they would kill her too; and when her tears would fall, a kind-hearted squaw was quick enough to throw some water in the poor woman's face, so that the men only laughed and thought it was a taunt, and not done to hide tears at all."

"I have not heard these old town stories for years. We ought to thank you heartily," said Miss Barbara, when the battle-ground had been shown and the club had heard all the interesting things that were known about the great fight. Then they came back by way of the old family burying-place and read the quaint epitaphs, which Mr. Picknell himself had cut deeper and kept from wearing away. It seemed that they never could forget the old farm's history.

"I maintain that every old place in town ought to have its history kept," said Mr. Picknell. "Now, you boys and girls, what do you know about the places where you live? Why don't you make town clerks of yourselves? Take the edges of almanacs, if you can't get courage to begin a blank-book, and make notes of things, so that dates will be kept for those who come after you. Most of you live where your great-grandfathers did, and you ought to know about the old folks. Most of what I've kept alive about this old farm I learned from my great-grandmother, who lived to be a very old woman, and liked to tell me stories in the long winter evenings, when I was a boy. Now we'll go and see where the beavers used to build, down here where the salt water makes up into the outlet of the brook. Plenty of their logs lay there moss-covered, when I was a grown man."

Somehow the getting acquainted with each other in a new way was the best part of the club, after all. It was quite another thing from even sitting side by side in school, to walk these two or three miles together. Betty Leicester had taught her Tideshead cronies something of her own lucky secret of taking and making the pleasures that were close at hand. It was great good fortune to get hold of a common wealth of interest and association by means of the club; and as Mr. Picknell and Miss Leicester talked about the founders and pioneers of the earliest Tideshead farms, there was not a boy nor girl who did not have a sense of pride in belonging to so valiant an old town. They could plan a dozen expeditions to places of historic interest. There had been even witches in Tideshead, and soldiers and scholars to find out about and remember. There was no better way of learning American history (as Miss Leicester said) than to study thoroughly the history of a single New England village. As for newer towns in the West, they were all children of some earlier settlements, and nobody could tell how far back a little careful study would lead.

There was time for a good game of tennis after the stories were told, and the play was watched with great excitement, but some of the club girls strayed about the old house, part of which had been a garrison-house. The doors stood open, and the sunshine fell pleasantly across the floors of the old rooms. Usually they meant to go picnicking, but to-day the Picknells had asked their friends to tea, and a delicious country supper it was. Then they all sang, and Mary Beck's clear voice, as usual, led all the rest. It was seven o'clock before the party was over. The evening was cooler than August evenings usually are, and after many leave-takings the club set off afoot toward the town.

"What a good time!" said Betty to the Grants and Aunt Barbara, for she had claimed one Grant and let Aunt Barbara walk with the other; and everybody said "What a good time!" at least twice, as they walked down the lane to the road. There they stopped for a minute to sing another verse of "Goodnight, ladies," and indeed went away singing along the road, until at last the steepness of the hill made them quiet. The Picknells, in their doorway, listened as long as they could.

At the top of the long hill the club, stopped for a minute, and kept very still to hear the hermit-thrushes singing, and did not notice at first that three persons were coming toward them, a tall man and a boy and girl. Suddenly Betty's heart gave a great beat. The taller figure was swinging a stick to and fro, in a way that she knew well; the boy was Harry Foster, and the girl was Nelly. Surely -- but the other? Oh, yes, it was papa! "Oh, papa!" and Betty gave a strange little laugh and flew before the rest of the club, who were still walking slowly and sedately, and threw herself into her father's arms. Then Miss Leicester hurried, too, and the rest of the club broke ranks, and felt for a minute if their peace of mind was troubled.

But Betty's papa was equal to this emergency. "This must be Becky, but how grown!" he said to Mary Beck, holding out his hand cordially; "and George Max, and the Grants, and -- Frank Crane, is it? I used to play with your father;" and so Mr. Leicester, pioneered by Betty, shook hands with everybody and was made most welcome.

"You see that I know you all very well through Betty! So nobody believed that I could come on the next train after my letter, and get here almost as soon?" he said, holding Betty's hand tighter than ever, and looking at her as if he wished to kiss her again. He did kiss her again, it being his own Betty. They were very fond of each other, these two; but some of their friends agreed with Aunt Barbara, who always said that her nephew was much too young to have the responsibility of so tall a girl as Betty Leicester.

Nobody noticed that Harry and Nelly Foster were there too, in the first moment of excitement, and so the first awkwardness of taking up every-day life again with their friends was passed over easily. As for our Betty, she fairly danced along the road as they went homeward, and could not bear to let go her hold of her father's hand. It was even more dear and delightful than she had dreamed to have him back again.

NOTES FOR CHAPTER XIV. THE OUT-OF-DOOR CLUB

packet-boat: This text is

inconsistent in hyphenating these words. I have not changed

these to make them consistent.

[ Back ]

terrible battle had been fought in

the old French and Indian war ... an account of it from Mr.

Parkman's history: Jewett says in "The Old Town of

Berwick, "Perhaps the most famous battle with the Indians was in

1690, when a party under the command of Hertel, a Frenchman, and

Hopegood, a sachem, attacked Newichawannock." This took place

early in the series of wars between France and the English

colonies (1689-1745). Jewett tells the story of the battle at

length, including the carrying of local hostages into Canada.

Jewett's notes on this battle refer to Parkman's Frontenac

and New France, Chap. XI. See "The Old Town of Berwick."

In Chapter 11 of Count Frontenac

and New France under Louis XIV (1877), Parkman gives this

account.

Through snow and ice and storm, Hertel and his band were moving on their prey. On the night of the

twenty-seventh of March, they lay hidden in the forest that bordered the farms and clearings of Salmon Falls. Their scouts reconnoitred the place, and found a fortified house with two stockade forts, built as a refuge for the settlers in case of alarm. Towards daybreak, Hertel, dividing his followers into three parties, made a sudden and simultaneous attack. The settlers, unconscious of danger, were in their beds. No watch was kept even in the so-called forts; and, when the French and Indians burst in, there was no time for their few tenants to gather for defence. The surprise was complete; and, after a short struggle, the assailants were successful at every point. They next turned upon the scattered farms of the neighborhood, burned houses, barns, and cattle, and laid the entire settlement in ashes. About thirty persons of both sexes and all ages were tomahawked or shot; and fifty-four, chiefly women and children, were made prisoners. Two Indian scouts now brought word that a party of English was advancing to the scene of havoc from Piscataqua, or Portsmouth, not many miles distant. Hertel called his men together, and began his retreat. The pursuers, a hundred and forty in number, overtook him about sunset at Wooster River, where the swollen stream was crossed by a narrow bridge. Hertel and his followers made a stand on the farther bank, killed and wounded a number of the English as they attempted to cross, kept up a brisk fire on the rest, held them in check till night, and then continued their retreat. The prisoners, or some of them, were given to the Indians, who tortured one or more of the men, and killed and tormented children and infants with a cruelty not always equalled by their heathen countrymen.

Worster's Brook in March 2005

Photo by Wendy Pirsig

Jewett also knew James Sullivan's and William Williamson's accounts of these events, which she read while writing "The Old Town of Berwick." She may also have read Francis Parkman's The Old Régime in Canada (1893) which shows sympathy to the French point of view. Eye-witness accounts differ in some details. See Emerson Baker for an eye-witness account:

James Sullivan says: "In the year 1690 a party under the command of one Hertel, a Frenchman, and Hopegood, a sachem, assaulted the plantation of Newichawanick [Salmon Falls River]; they killed thirty men, and the rest of the people, after an obstinate and courageous defence, surrendered at discretion. The captives were fifty-four, the greater part of whom were women and children. The enemy burned all the houses and mills, and taking with them what plunder they could carry, retreated to the northward. A party of one hundred and forty men collected from the neighbouring towns, pursued and came up with the Savages on Worster's River, at a narrow bridge. Hertel had expected a pursuit, and had placed his people in a posture of defence. The engagement was warm, and continued the whole of an afternoon; but as the men on both sides were shielded by the trees and brush, there was no great slaughter; four or five of the English, and two of the Savages were killed, a Frenchman was wounded and taken prisoner" (History of the District of Maine, 250-1; See also William Williamson, v. 2, ch. 2).

Francis Parkman says, in The Old Régime in

Canada (1874), "When ... a band of French and Indians

issued from the forest and fell upon the fort and settlement of

Salmon Falls, it was François Hertel who led the attack; and

when the retiring victors were hard pressed by an overwhelming

force, it was he who, sword in hand, held the pursuers in check

at the bridge of Wooster River, and covered the retreat of his

men. He was ennobled for his services, and died at the age

of 80, the founder of one of the most distinguished families of

Canada. To the New England of old he was the abhorred

chief of Popish malignants and murdering savages. The New

England of to-day will be more just to the brave defender of his

country and his faith" (Library of America edition, 1152-3).

Norma Keim writes, "In 1688 a series of

French and Indian Wars began, making life in our area unsettled

and often dangerous. Some of these wars were extensions of war

in Europe between France and England. In the New World, the

French had the support of displaced natives from western and

eastern Abenaki tribes as well as Indians from Canada; the

English had their native allies as well. The French and Indians

made numerous attempts to disrupt English settlements in New

England, lasting well into the 1700s. It was to the benefit of

France that English settlements failed, for settlements like

Salmon Falls and Quamphegan were providing masts for the English

navy in Europe.

"Salmon Falls, Quamphegan and Old

Fields felt the effect of King William's War (1688). Salmon

Falls was all but destroyed in the surprise attack of March 18,

1689. A group of French from Canada and their Indian allies

burned homes and mills, killed many settlers and captured

others, a young woman named Mehitable Goodwin among them. This

attack may also have been responsible for the burning of the

Humphrey Chadbourne homestead."

This raid of 1689/90 (both dates get

used because of the change in calendar), as Keim recounts, swept

through the Upper Landing area; Emerson Baker believes this

attack destroyed the Chadbourne house at the mouth of the Great

Works River.

(Research assistance: Emerson Baker,

Norma Keim, Wendy Pirsig).

[ Back ]

hide tears: Jewett recounts

this story also in "The Old Town of Berwick" (1894) and in The

Tory Lover, Chapter 32 (1901). This is the story

of Hetty Goodwin. As she explains in "The Old Town

of Berwick," Jewett knows the story from local oral history, but

she also points out that probably the first printed account

appears in Cotton Mather's works. She mentions Magnalia

Christi Americana (1702); the story also appears in Decennium

Luctuosum (1699). Jewett has changed some details in

this version, shortening the captivity in Canada to three

years. Significant parts of Jewett's fullest version of

the story in "The Old Town of Berwick" cannot be verified, and

probably are legendary, notably the story of the kindly Indian

woman and the story of Hetty's second marriage.

In all three of the above versions,

Jewett relates that after Hetty's captors killed her son, they

threatened to kill her as well if she would not control her

grief. Seeing that she could not keep from weeping, a

kindly Indian woman with "a mother's heart" splashed water in

her face, creating -- through an apparent act of cruelty -- a

rationale for Hetty's tears, and saving her from her captors'

wrath. Useful as this story is to Jewett in her two

novels, it is unlikely to be true. The multiple accounts

we have of Hertel's raid indicate that there were no women among

the raiders. The situation differs from captivities in

King Philip's war (1675-6), such as that of Mary Rowlandson,

when the raiders were exclusively Native Americans with more or

less local camps, through which prisoners could be passed on

their route to Canada. Hertel's raiders came from Three Rivers,

in Canada, and were made up of French soldiers and an Indian

force, mainly Sokoki, who would be familiar with the Salmon

Falls area, but not recently residing there. The raiders

had to move quickly through rough terrain in the winter.

At his website, historian Emerson Baker reprints a transcription

of an eye-witness account: “French Captive Examination from Piscataway

19th March 1690”. Failing to mention any women

traveling with the raiders, this account confirms the military

nature of the raid: "yt they came by ordr of the french Govr at

Canada & that both french & Indians are in pay at ten

Livers p month."

Though it is not impossible that women

accompanied this group, it is unlikely, and there is no mention

of Indian women in written accounts from Mather through Parkman

to more recent summaries, such as that in Chester B. Price's

description of "Historic Indian Trails of New Hampshire" of the

Newichwannock-Sokoki trail, which the raiders followed in their

escape (reprinted in The Indian Heritage of New Hampshire

and Northern New England. McFarland: Jefferson, NC, 2002,

pp. 160-162). Colin Calloway's account emphasizes the

arduous military character of the raid: " … twenty-four French,

twenty to twenty-four Sokokis, and five Algonquins -- led by

François Sieur d'Hertel -- left Three Rivers, crossed Lake

Memphremagog to the Connecticut River, and, after three months

hard traveling, attacked Salmon Falls on the New Hampshire

frontier" (The Western Abenaki of Vermont 1600-1800.

Norman: U Oklahoma P, 1990, pp. 94-5). A. T. Vaughan and

E. W. Clark say that Governor Frontenac, who ordered the raids,

had recently lowered the bounty on scalps and raised it on

prisoners, thus encouraging the raiders to bring more prisoners

to Canada (Puritans among the Indians, 136). In The

Captor's Narrative, William H. Foster points out the need

for captive labor in the developing French colony.

We may also notice another difference

between early accounts of the captivity and more recent accounts

of the raid. Mather and Parkman focus on the prisoners,

emphasizing that they were "given to the Indians," and as a

result suffered special cruelties, such as the killing of

children and various tortures. Both, of course, are making

cases against the Indians. Mather wishes to persuade

readers that Indians are bestial minions of Satan, to be either

converted or extirpated from the Christian colonies.

Parkman wishes to persuade readers that Indians are a savage

race, generally incapable of civilization, and, therefore, those

who cannot convert to Protestant Christianity are doomed to

extinction by historical forces represented by America's

Manifest Destiny. More recent accounts, such as

Calloway's, emphasize the conditions of international warfare

between France and England, and the military character of this

and other raids. It was the French intention to terrorize

English colonists on the frontier and drive them out. The

British had the same intentions toward the French. Both

used Indians in warfare in part because they could do what

"civilized" soldiers were not allowed to do, ruthlessly kill

prisoners who proved incapable of keeping up with the necessary

pace of the raiders as they struck and retreated.

Calloway, for example, emphasizes that the Frenchman d'Hertel

was in command, while earlier writers, whom Jewett follows,

typically name the Indian, Hopehood, as a co-commander.

The second element of Hetty Goodwin's story that probably is legendary appears only in "The Old Town of Berwick," the assertion that Goodwin, believing her first husband dead, remarried while held prisoner in Canada.

In Old Kittery and her Families, Everett Stackpole, doubting the marriage, provides this account:

Other captives were Thomas Goodwin and his wife, who was Mehitable, daughter of Lieut. Roger Plaisted. The husband and wife were assigned to different bands of Indians and so remained apart. After his escape he is said to have returned to Canada for the ransom of his wife. An account of her sufferings was written by Rev. Cotton Mather in his Magnalia, and has been often republished. Her son, about five months old, was barbarously murdered before her eyes and hanged by the neck in a forked bough of a tree. After terrible sufferings from grief, cold and hunger, she arrived at Montreal. The record of her baptism, written in French, has been kindly furnished me by Miss C. Alice Baker, who has published much about the captives taken in the French and Indian Wars. The translation is as follows:Again, it remains possible that Hetty remarried in Canada and perhaps even bore one or more children while there, but the marriage would have had to take place, as Stackpole points out, after May of 1693. C. Alice Baker's inquiry elicited no record of a marriage, and Foster's research for The Captor's Narrative turned up no evidence that Hetty married in Canada. He discusses her as among two married English women who converted to Catholicism during their captivities (144).

"Monday, 11 May, 1693, there was solemnly baptized an English woman called in her own country Mehetabel, and by the French who captured her in war, 18 March 1690, Esther, who was born at Barvic, in New England, 30 April (old style, or 19 May new style) 1670, of the marriage of Roger Pleisted, Protestant, and Olive Coleman of the same religion, and was married to Thomas Gouden [Goodwin] also Protestant. She has lived for about three years in the service of Mademoiselle de Nauguiere [written also de la Naudiere]. She was named Marie Esther. Her godfather was Messire Hector de Catlieres, Chevalier, Governor for the King in the Isle of Montreal and its vicinity. Her godmother was Damoiselle Marguerite Renee Denis, widow of Monsieur Naugiere de la Perade, during his life Captain of the Guard of Monsieur le Conte de Frontenac, Governor of New France. The baptism was performed by M. Francois Dolie de Casson, Grand Vicar of the most Illustrious and most Reverend Monseigneur Bishop of Quebec."

(Signed) Chevalier de Catlieres,

Marguerite renee denis,

Fran. Doelier,

E. Guyoth, Cure.I have heard the tradition from one of her descendants that Mehitabel Goodwin was married in Canada to a man named Rand (some say Pain) and that descendants are living in Portsmouth. This is highly improbable. She was baptized in May, 1693, and could not have been married before, and she was ransomed in October, 1695. The Rands of Portsmouth are all, doubtless, descended from the Francis Rand who came over in the company of Capt. John Mason. (Old Kittery and Her Families, 1903, pp. 165-6).

One wonders about how the story of this marriage made it into the oral history of South Berwick and so, into Jewett's account of Hetty in "The Old Town of Berwick." It certainly adds to the pathos of the 5-years separation of the young married couple, but it also adds complications that beg for deeper exploration. How did Hetty feel about leaving her second husband to return with her first? How did her children by the second marriage end up in nearby Portsmouth, NH? What relationships did they sustain with their mother?

Jewett does not mention Hetty's supposed second marriage in either of her novels, probably because it would have seemed inappropriate and would have worked against her reasons for bringing Hetty's story into her narratives. Indeed, in The Tory Lover (Chapter 32), Madam Wallingford emphasizes her ancestor's extreme reticence about her trials, suggesting that Hetty was not herself the witness who provided Cotton Mather with his account of Hetty's captivity. Possibly, C. Alice Baker, Jewett's close friend according to biographer Paula Blanchard (Sarah Orne Jewett, pp. 225-6), told Jewett about the baptism between 1894 and the publication of The Tory Lover in 1901. Baker did not retell Hetty's story in True Stories of New England Captives Carried to Canada During the Old French and Indian Wars (1897), but she may have completed her research on Hetty Goodwin before 1897.

Though this detail seems less important to Jewett's work, there also is lack of clarity about how Hetty was rescued and returned home. Jewett indicates that Hetty's husband, Thomas, personally undertook the redemption, but Emma Lewis Coleman says, "'Hitobl Goodin' was one of those redeemed in Oct 1695 by Mathew Cary" (Coleman, New England Captives Carried to Canada I [1925]: 185-186). Vaughan and Clark in Puritans among the Indians indicate that Hetty Goodwin was among the twenty-two prisoners brought back to Boston from Canada by Matthew Carey/Cary aboard the Tryal in October-November, 1695 (157).

[ Back ]

"Goodnight, Ladies": “Goodnight, Ladies”is attributed to Edwin

Pearce Christy (November 28, 1815 – May 21, 1862), the first

version appearing in 1847 and the complete version in 1867.

Verse 1: Goodnight, ladies! Goodnight, ladies! Goodnight,

ladies! We're going to leave you now.

Chorus: Merrily we roll along, roll along, roll along,

O'er the dark blue sea.

Verse 2: Farewell, Ladies! Farewell, ladies! Farewell,

ladies! We're going to leave you now.

Verse 3: Sweet dreams, ladies! Sweet dreams, ladies! Sweet

dreams, ladies! We're going to leave you now.

Beatrice Stevens

THE STARLIGHT COMES IN.

There was a most joyful evening in the old Leicester house. Everybody forgot to speak about Betty's going to bed, and even Aunt Mary was in high spirits. It was wonderful how much good a little excitement did for her, and Betty had learned that an effort to be entertaining always brought the pleasant reward of saving Aunt Mary from a miserable, tedious morning or afternoon. When she waked next morning, her first thought was about papa, and her next that Aunt Mary was likely to have a headache after sitting up so late. Betty herself was tired, and felt as if it were the day after the fair; but when she hurried down to breakfast she found Aunt Barbara alone, and was told that papa had risen at four o'clock, and, as she expressed it to Aunt Mary a little later, stolen his breakfast from Serena and gone down to Riverport on the packet, tide having served at that early hour.

"I heard a clacketing in the kitchen closet," said Serena, "and I just got my skirt an' a cape on to me an' flew down to see what 't was. I expected somebody was took with fits; an' there was y'r father with both his hands full o' somethin' he'd collected to stay himself with, an' he looked 's much o' a boy 's ever he did, and I so remarked, an' he told me he was goin' to Riverport. 'Want a little change, I s'pose?' says I, an' he laughed good an' clipped it out o' the door and down towards the landin'."

"I wonder what he's after now, Serena?" said Betty sagely, but Serena shook her head absently. It was evident to Betty's mind that papa had shaken off all thought of care, and was taking steps towards some desired form of enjoyment. He had been disappointed the evening before to find that there were hardly any boats to be had. Very likely he meant to bring one up on the packet that afternoon; but Betty was disappointed not to find him in the house, and thought that he might have called her to go down on the packet with him. She felt as if she were going to have a long and dull morning.

However, she found that Aunt Mary was awake and in a cheerful frame, so she brought her boots in, and sat by the garden window while she put some new buttons on with the delightful little clamps that save so many difficult stitches. Aunt Mary was already dressed, though it was only nine o'clock, and was seated before an open bureau drawer, which her grandniece had learned to recognize as a good sign. Aunt Mary had endless treasures of the past carefully tucked away in little bundles and boxes, and she liked to look these over, and to show them to Betty, and tell their history. She listened with great eagerness to Betty's account of papa's departure.

"I was afraid that you would feel tired this morning," said the girl, turning a bright face toward her aunt.

"I am sure I expected it myself," replied Aunt Mary plaintively, "but it isn't neuralgia weather, perhaps. At any rate, I am none the worse."

"I believe that a good frolic is the very best thing for you," insisted Betty, feeling very bold; but Aunt Mary received this news amiably, though she made no reply. Betty had recovered by this time from her sense of bitter wrong at her father's departure, and after she had talked with Aunt Mary a little while about the grand success of the Out-of-Door Club, she went her ways to find Becky.

Becky was in a very friendly mood, and admired Mr. Leicester, and wondered too at ever having been afraid of him in other years, when she used to see him walking sedately down the street.

"Papa is very sober sometimes when he is hard at work," explained Betty with eagerness. "He gets very tired, and then -- oh, I don't mean that papa is ever aggravating, but for days and days I know that he is working hard and can't stop to hear about my troubles, so I try not to talk to him; but he always makes up for it after a while. I don't mind now, but when I was a little girl and first went away from here I used to be lonely, and even cry sometimes, and of course I didn't understand. We get on beautifully now, and I like to read so much that I can always cover up the dull times with a nice book."

"Do they last long, -- the dull times?" asked Mary Beck in an unusually sympathetic voice. Betty had spoken sadly, and it dawned upon her friend's mind that life was not all a holiday even to Betty Leicester.

"Ever so long," answered Betty

briskly; "but you see I have my mending and housekeeping when we

are in lodgings. We are masters of the situation now, papa

always says; but when I was too small to look after him, we used

to have to depend upon old lodging-house women, and they made us

miserable, though I love them all for the sake of the good ones

who will let you go into the kitchen yourself and make a cup of

tea for papa just right, and be honest and good, and cry when

you go away instead of clamming the door. Oh, I could tell you

stories, Mary Eliza Beck!" and Betty took one or two frisky

steps along the sidewalk as if she meant to dance. Mary Beck

felt as if she were looking out of a very small and high garret

window at a vast and surprising world. She was not sure that she

should not like to keep house in country lodgings, though, and

order the dinner, and have a housekeeping purse, as Betty had

done these three or four years. They had often talked about

these experiences; but Becky's heart always faltered when she

thought of being alone in strange houses and walking alone in

strange streets. Sometimes Betty had delightful visits, and

excellent town lodgings, and diversified hotel life of the most

entertaining sort. She seemed to be thinking about all this and

reflecting upon it deeply. "I wish that papa and I were going to

be here a year," she said. "I love Tideshead."

Mr. Leicester did not wait to come back with the packet boat, but appeared by the stage from the railway station in good season for dinner. He was very hungry, and looked well satisfied with his morning's work, and he told Betty that she should know toward the end of the afternoon the reason of his going to Riverport, so that there was nothing to do but to wait. She was disappointed, because she had fancied that he meant to bring home a new row-boat; perhaps, after all, he had made some arrangements about it. Why, yes! it might be coming up by the packet, and they would go out together that very evening. Betty could hardly wait for the hour to come.

When dinner was over, papa was enticed up to see the cubby-house, while the aunts took their nap. There was a little roast pig for dinner, and Aunt Barbara had been disappointed to find that her guest had gone away, as it was his favorite dinner; but his unexpected return made up for everything, and they had a great deal of good fun. Papa was in the best of spirits, and went out to speak to Serena about the batter puddling as soon as Aunt Barbara rose from her chair.

"Now don't you tell me you don't get them batter puddings a sight better in the dwellings of the rich and great," insisted Serena, with great complacency. "Setting down to feast with lords and dukes, same 's you do, you must eat of the best the year round. We do season the sauce well, I will allow. Miss Barbara, she always thinks it may need a drop more."

"Serena," said Betty's father solemnly, "I assure you that I have eaten a slice of bacon between two tough pieces of hard tack for my dinner many a day this summer, and I haven't had such a batter pudding since the last one you made yourself."

"You don't tell me they're goin' out o' fashion," said Serena, much shocked "I know some ain't got the knack o' makin' 'em!"

Betty stood by, enjoying the conversation. Serena always said proudly that a great light of intellect would have been lost to the world if she had not rescued Mr. Leicester from the duck-pond when he was a boy, and they were indeed the best of friends. Serena's heart rejoiced when anybody praised her cooking, and she turned away now toward the pantry with a beaming smile, while the father and daughter went up to the garret.

It was hot there at this time of day; still the great elms outside kept the sun from shining directly on the roof, and a light breeze was blowing in at the dormer window.

Mr. Leicester sat down in the high-backed wooden rocking-chair, and looked about the quaint little place with evident pleasure. Betty was perched on the window-sill. She had looked forward eagerly to this moment.

"There is my old butterfly-net," he exclaimed, "and my minerals, and -- why, all the old traps! Where did you find them? I remember that once I came up here and found everything cleared away but the gun, -- they were afraid to touch that."

"I looked in the boxes under the eaves," explained Betty. "Your little Fourth of July cannon is there in the dark corner. I had it out at first, but Becky tumbled over it three times, and once Aunt Mary heard the noise and had a palpitation of the heart, so I pushed it back again out of the way. I did so wish that you were here to fire it. I had almost forgotten what fun the Fourth is. I wrote you all about it, didn't I?"

"Some day we will come to Tideshead and have a great celebration, to make up for losing that," said papa. "Betty, my child, I'm sleepy. I don't know whether it is this rocking-chair or Serena's dinner."

"Perhaps it was getting up so early in the morning," suggested Betty. "Go to sleep, papa. I'll say some of my new pieces of poetry. I learned all you gave me, and some others beside."

"Not the 'Scholar Gypsy,' I suppose?"

"Yes, indeed," said Betty. "The last of it was hard, but all those verses about the fields are lovely, and make me remember that spring when we lived in Oxford. That was the only long one you gave me. I am not sure that I can say it without the book. I always play that I am in the 'high field corner' looking down at the meadows, and I can remember the first pages beautifully."

Papa's eyes were already shut, and by the time Betty had said

"All the live murmur of a summer's day"

she found that he was fast asleep. She stole a glance at him now and then, and a little pang went through her heart as she saw that his hair was really growing gray. Aunt Mary and Aunt Barbara appeared to believe that he was hardly more than a boy, but to Betty thirty-nine years was a long lifetime, and indeed her father had achieved much more than most men of his age. She was afraid of waking him and kept very still, so that a sparrow lit on the window-sill and looked at her a moment or two before he flew away again. She could even hear the pigeons walking on the roof overhead and hopping on the shingles, with a tap, from the little fence that went about the house-top. When Mr. Leicester waked he still wished to hear the "Scholar Gypsy," which was accordingly begun again, and repeated with only two or three stops. Sometimes they said a verse together, and then they fell to talking about some of the people whom they both loved in Oxford, and had a delightful hour together. At first Betty had not liked to learn long poems, and thought her father was stern and inconsiderate in choosing such old and sober ones; but she was already beginning to see a reason for it, and was glad, if for nothing else, to know the poems papa himself liked best, even if she did not wholly understand them. It was easy now to remember a new one, for she had learned so many. Aunt Barbara was much pleased with this accomplishment, for she had learned a great many herself in her lifetime. It seemed to be an old custom in the Leicester family, and Betty thought one day that she could let this gift stand in the place of singing as Becky could; one's own friends were not apt to care so much for poetry, but older people liked to be "repeated" to. One night, however, she had said Tennyson's ballad of "The Revenge" to Harry Foster and Nelly as they came up the river, and they liked it surprisingly.

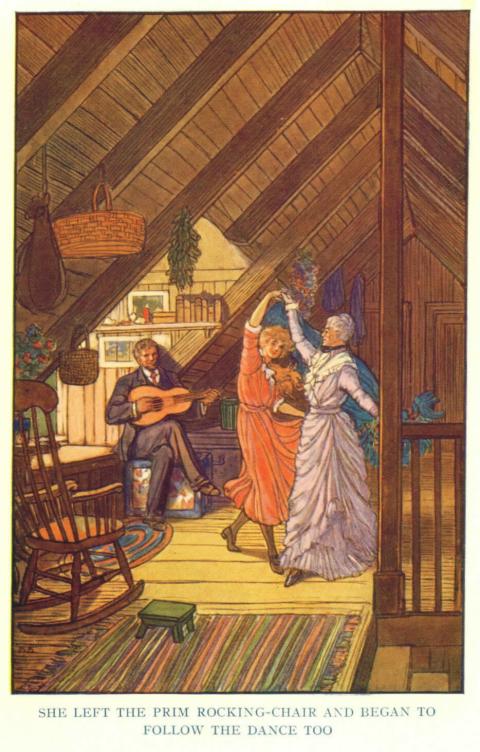

Papa reached for the old guitar presently and after mending the broken strings he began to sing a delightful little Italian song, a great favorite of Betty's. Then there was a step on the stairs, Aunt Barbara's dignified head appeared behind the railing, and they called her to come up and join them.

"I felt as if there must be ghosts walking in daylight when I heard the old guitar," she said a little wistfully. When she was seated in the rocking-chair and Betty's father had pulled forward a flowered tea-chest for himself, he went on with his singing, and then played a Spanish dancing tune, with a nod to Betty, so that she skipped at once to the open garret-floor and took the pretty steps with much gayety. Aunt Barbara smiled and kept time with her foot; then she left the prim rocking-chair and began to follow the dance too, soberly chasing Betty and receding and even twirling her about, until they were both out of breath and came back to their places very warm and excited. They looked strangely alike as they danced. Betty was almost as tall and only a little more quick and graceful than her grandaunt.

"It is such fun to be just the same age as you and papa," insisted Betty. "We do everything together now." She took on a pretty grown-up air, and looked at Aunt Barbara admiringly. It was only this summer that she had begun to understand how young grown people really are. Aunt Mary seemed much older because she had stopped doing so many pleasant things. This garret dance was a thing to remember. Betty liked Aunt Barbara better every day, but it had never occurred to her that she knew that particular Spanish dance. An army officer's wife had taught it to Betty and some of her friends the summer she was in the Isle of Wight. Becky had been brought up to be very doubtful about dancing, which was a great pity, for she was apt to be stiff and awkward when she walked or tried to move about in the room. Somehow she moved her feet as if they had been made too heavy for her, but she learned a good deal from trying to keep step as she walked with Betty, who was naturally light-footed.

Mr. Leicester put down the guitar at last, and said that he had an errand to do, and that Betty had better come along.

Beatrice Stevens

"Can't you sit still five minutes, either of you?" maliciously asked Aunt Barbara, who had quite regained her breath. "I really did not know how cozy this corner was. I must say that I had forgot to associate it with anything but Serena's and my putting away blankets in the spring. I used to like to sit by the window and read when I was your age, Betty. In those days I could look over this nearest elm and see way down the river, just as you can now in winter when the leaves are gone. I dare say the three generations before me have played here too. I am so glad that we could have Betty this summer; it is time she began to strike her roots a little deeper here."

"Yes," said Mr. Leicester, "but I can't do without her, my only Betsey!" and they all laughed, but Betty had a sudden suspicion that Aunt Barbara would try to keep her altogether now. This frightened our friend a little, for though she loved the old home dearly, she must take care of papa. It was her place to take care of him now; she had been looking over his damaged wardrobe most anxiously that morning, as if her own had never known ruin. His outside clothes were well enough, but alas for his pocket handkerchiefs and stockings! He looked a little pale, too, and as if he had on the whole been badly neglected in minor ways.

But there never was a more cheerful and contented papa, as they walked toward the river together hand-in-hand, in the fashion of Betty's childhood. They found that the packet had come in, and there was a group of spectators on the old wharf, who were looking eagerly at something which proved to be a large cat-boat which the packet had in tow. Mr. Leicester left Betty suddenly and went to the wharf's edge.

"Did you have any trouble bringing her up?" he asked.

"Bless ye, no, sir," said the packet's skipper; "didn't hinder us one grain; had a clever little breeze right astern all the way up."

"Look here, Betty," said papa, returning presently. "I went down this morning to hunt for a dory with a sail, and I saw this cat-boat which somebody was willing to let, and I have hired it for a while. I wish to look up the river shell-fish a bit; it's not altogether play, I mean you to understand."

"Oh, papa!" cried Betty joyfully. "The only thing we needed was a nice boat. But you can't have clutters in pots and pans at Aunt Barbara's, can you, and your works going on? Serena won't like it, and she can be quite terrible, you know!"

'Come on board and look at her,' said Mr. Leicester.

Beatrice Stevens

"Come on board and look at her," said Mr. Leicester, regardless of the terrors of Serena's disapproval. The cat-boat carried a jib beside a good-sized mainsail, and had a comfortable little cabin with a tiny stove and two berths and plenty of lockers. Two young men had just spent their vacation in her, coasting eastward, and one of them told Mr. Leicester that she was the quickest and steadiest boat he ever saw, sailing close to the wind and answering her rudder capitally. They had lived on board altogether and made themselves very comfortable indeed. There was a light little flat-bottomed boat for tender, and the white cat-boat itself had been newly painted with gilt lettering across the stern, Starlight, Riverport.

"I can ask the Out-of-Door Club one day next week," announced Betty, with great enthusiasm. "Isn't she clean and pretty? Won't Aunt Barbara like her, papa?"

"I must look about for some one to help me to sail her," said Mr. Leicester, with uncommon gravity. "What do you think of young Foster? He must know the river well, and his fishing may be falling off a little now. It would be a good way to help him, don't you think so?"

Betty's eyes shone with joy. "Oh, yes," she said; "they do have such a hard time now. Nelly told me so yesterday morning. It has cost them so much lately. Harry has been trying to get something to do in Riverport."

They were busy anchoring the Starlight out in the stream, and now Mr. Leicester helped Betty over the side into the tender and sculled her ashore. Some of the men on the wharf had disappeared, but others were still there, and there was a great bustle of unloading some bags of grain from the packet. Mr. Leicester invited one of his old acquaintances who asked many questions to come out and see the cat-boat, and as Betty hurried up the street to the house she saw over her shoulder that a large company in small leaky crafts had surrounded the pretty Starlight like pirates. It was apt to be very dull in Tideshead for many of the idle citizens, and Mr. Leicester's return was always hailed with delight. It was nearly tea-time, so that Betty could not go over to tell Mary Beck the good news; but one white handkerchief, meaning Come over, was quickly displayed on the pear-tree branch, and while Betty was getting dressed in a much-needed fresh gown for tea Becky kindly appeared, and was delighted with the good news. She had seen the Starlight already from a distance.

"My father used to have a splendid sail-boat," said fatherless Becky with much wistfulness, and Betty put her arms round her and gave her a warm kiss. Sometimes it seemed that whatever one had the other lacked.

NOTES FOR CHAPTER XV. THE STARLIGHT COMES IN

Fourth of July: Annual American

holiday celebrating the signing of the Declaration of

Independence and the beginning of the American Revolution of

1776.

[ Back ]

'The Scholar Gypsy'... "All the

live murmur of a summer's day": Matthew Arnold (1822-1888)

published his poem, "The Scholar Gypsy" in 1853. "The Scholar

Gypsy" is 250 lines. This is the twentieth line of the poem.

[ Back ]

Tennyson's ballad of "The Revenge":

Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) published "The Revenge: A

Ballad of the Fleet" in 1878. The Grolier Multimedia

Encyclopedia says, "Sir Richard Grenville, b. c.1542, d.

Sept. 12, 1591, was an English naval hero in the service of

Queen Elizabeth I. He was a cousin of Sir Walter Raleigh, and in

1585 he led the expedition that founded Raleigh's "Lost Colony"

on Roanoke Island, N.C. In 1591, Grenville joined an English

fleet intending to intercept Spanish treasure ships off the

Azores. His ship, the Revenge, was separated from the rest and

forced to engage a Spanish war fleet by itself. Grenville fought

a heroic 15-hour battle, but he was mortally wounded and his

ship was captured."

[ Back ]

cat-boat: a type of sailboat.

[ Back ]

Beatrice Stevens

DOWN THE RIVER.