Main Contents & Search

Harper's Text

MÈRE POCHETTE.

I.

The French Canadian village of Bonaventure seemed to have strayed away from its companions and lost itself in the interminable wilderness that lies between the settlements of the Eastern States and the St. Lawrence country. For many years the community was self-centred and the nearest market-town too far away to be of consequence. A visionary seigneur, an aerial, castle-building Frenchman who never took the trouble to leave his own château except to taste the joys of Paris, had sent out a colony to this new possession, but it dwindled away and did not flourish. The factor was proved a cheat at last, and the old count shrugged his shoulders, smiled, and resigned himself. Some of the disappointed settlers retraced the trail to the great river, but a few remained; they had their gardens and their pigs and chickens. Life might be far worse elsewhere.

The lumber men came by and by with their long axes; the old seigneur's timber made rich other men than his heirs, while Bonaventure flourished for a season with new prosperity. The rough road over which the great logs were hauled to a distant stream proved a permanent thoroughfare, and now and then a stranger came and stayed. The mother-church sent a pastor to teach and pray among these neglected children, and a sharp spire, in glistening armor of tin, rose above the later growth of spruces and maples that had hastened to conceal the great stumps of the vanished pines. The first log huts were one by one replaced by the high-roofed houses of regulation shape and size which one may see in Beauport, in Lorette, in a hundred other villages of the French régime. This was a small town, this Bonaventure, but it valued itself even more than was necessary in later years. The hereditary owners of the petty estates were apt to look with suspicion upon any new-comers, and when it was ascertained that a man called Joseph Pochette from the neighborhood of Quebec had bought the Rispé house and land, with a piece of outlying forest, there was a bitter arraignment of such proceedings. Mère Poulette, who kept the village shop in her front room, was particularly angry, though one would have believed her ready to welcome a new customer. "Some crime has forced him to abandon his birthplace," she exclaimed, and glared round upon the startled company.

But Joseph himself, a good fellow enough, quickly pacified the neighborhood, especially as he died of fever within a year or two after his appearance in Bonaventure society. His funeral was a satisfactory one, but Mère Pochette had already drawn down upon herself the dislike of her associates. She was wickedly proud and independent, a black-hearted schemer who cared only to grow rich; and when she went by the houses with her fatherless baby in her arms, she won no compassion, for she asked none, and all hearts were on the defensive. Even the fact that old Poulette had not succeeded in making a good bargain with widow Manon for her woodland was not lost sight of, for had not this stranger the soul of an aristocrat under her peasant's clothes.

At last there was another change at Bonaventure; one day the surveyors came with their chains and compasses, and before anybody could take time to fairly consider such an innovation the new railroad was pushing its way northward through the swamps and forests. Now the piece of worthless waste which Manon would not sell to Poulette -- the obstinate woman! -- was sold to the company at an excellent price. It was all a piece of luck, but the indignant chorus of the little shop could not forgive such an outrage. As time went on, however, Providence seemed to repay her for her behavior. Her only child made an unfortunate match with a foreigner, though it was well known that Mère Pochette meant to buy the chit a rich husband. Then she was presently burdened with an orphan grandchild and the chorus chattered and sing-songed their satisfaction. It took a stalwart character to keep its own way with almost an aspect of serenity; there was no light task in facing the dislike and distrust of one's townspeople, though as Mère Pochette grew richer and, if the truth must be told, prouder and more powerful year by year, her neighbors were civil enough to her face and even obsequious, the worst of them, whatever they might have said in winter evenings behind her back. She had devoted all her energies to securing a generous dowry for her daughter. The mistaken girl had disregarded this provision, had thwarted her mother's wishes, and had suffered enough, God knows! Now Mère Pochette's object in life was the wise ordering of the little granddaughter, and when, by and by, she was enviably settled in life, the sneering by-standers might say what they chose. This noble worldly ambition made Mère Pochette glad to work early and late and to toil and save. She would put her grandchild where all the village might not touch her. A career of pride and happiness should be put into little Manon's future.

The neighbors were apt to look suspiciously at little Manon, the granddaughter, as she went by their houses with quick, light footsteps. She was of mixed race at any rate. Her father was a young engineer from the States who had married this old Manon Pochette's handsome daughter, and they had held their heads too high, the fools! and shaken the dust of the little village off their feet. It was the way of the world; one April day their ribbons were flying, and they laughed aloud together and never cared to cast a look behind them at old friends; the next spring a letter came, and the priest read it to the widow, that her daughter Jeanne was dead. Presently the young engineer, broken and spent by chills and fever and hard fortune, came creeping back with a cough and a white scared face and an ailing motherless baby to the high-roofed cottage. Old Manon blessed herself, and waved her thrifty hands in dismay. She rolled her eyes and made grimaces, and became eloquent in patois sentences which her son-in-law did not even try to translate for himself. Then she mounted to her garret and came down presently with the dusty cradle. The wailing child was fumbled and tumbled and smothered in coverings that seemed to have been waiting for it, and the waning fire in the high, square stove was rekindled, though the May sun shone in benignantly. The young man coughed less often for a blissful hour; he sank into an angular chair at the chimney corner, and hid his face in his hands and cried silently.

The little house had seemed as full of romance as a scene at a play, the year before; he had not concerned himself with the rest of the habitants of Bonaventure; they were only the tawdry stage crowd that weeps and exclaims in perfunctory unison while the hero and heroine suffer real pains and know true joys just behind the footlights. Now the sentiment and the amusement had faded out entirely. The garden of his life had suddenly been blackened by the most chilling of frosts; it was late spring here in old Manon's plain house, she was a stout, unsympathetic old French Canadian; and as he had come from the railway station tired to death with his long journey and finding even the baby a heavy burden, he had not been blind or deaf to the unspoken jeers and curious glances which were ready for him at almost every house. He had once been a hero in his petty fashion; the men of the village had been obliged to obey him for a short three months; he had disdained the women, all except the pretty creature who had become his wife. Whether he had regretted his marriage nobody would ever know. It was a dangerous experiment to carry her among young girls whose training and schooling had been of a better sort, but now there was nothing sweeter or sadder to think of than the days when they had been deep in love. Poor Jeanne! her grave was left alone in an unsheltered western burying-ground. He could not see even that low sandy mound again, and now that he had in despair begged and borrowed his way hither to bring little Manon to her grandmother, he felt that the great mystery of death would soon be made plain to him. The few men who remembered him on this new railroad had been very kind, and for a few hours his reinstatement to a semblance of his former position and relationship had brought back something of his old good comradeship and vigor. He even criticized the finish of the work which had been done since he went away, and discussed it with an acquaintance who was now an official of the company and journeying prosperously to the terminus at Quebec. A kind-hearted woman had helped him to take care of the baby; he had seen her eyes fill with tears at his bungling attempt to undress it the night before, but he could not cry himself. He had sometimes looked at the little trimming of the baby's dress for a half hour at a time, he remembered so well the tune his wife had sung as she sewed it on, and held and shaped it with her fingers, months ago. It seemed like years already, though the baby's short life almost linked that time to this.

. . . . . . . . .

The fire crackled in the box-stove, the little child was sound asleep in the great cradle; old Manon, the grandmother, stepped heavily to and fro, and now and then put a bowl or a plate on the kitchen-table. She muttered something about her poor little one, and clasped her hands ostentatiously, and seemed to consider the question of prayer, but gave a savage glance at the poor son-in-law instead, and went on her slow rounds about the room. He noticed that she looked ten years older than she had the year before, but it hardly surprised him, all the rest of the world was so changed, and then he looked wistfully at the plump bed in the corner, and longed to lie there and forget his weariness in sleep. He and Jeanne had run away to be married; her mother would not hear to the match, because this would-be son-in-law was not a Catholic. When he looked up at the mantel shelf, however, his own letter that told the stern mistress of the house of her daughter's death was displayed beside the brass candlestick and the little picture of St. Joseph which had been blessed by the archbishop. After all, was it not something to have a literate son-in-law?

In the next house and the house beyond, the neighbors were talking, and watching by turns the door which the traveler had lately entered. "It is well that Manon Pochette has made the round of the blessed stations of the cross every morning these many years," said the fierce dame who sat in her little shop across the way. "The saints warned her, she will be poor indeed and incapable, without their help, to bring up an infant of no gifts; a perfectly deplorable occasion, my friends," and she looked from one to another, while a doleful neighbor closed her eyes and groaned loudly. It was a great while since anything so interesting had happened in Bonaventure.

"He has been robbed of his haughty behavior," continued the first speaker. "A wicked pride indeed, but an abased manner of return to an insulted house. He will not toss pennies now to good Justin Poulette, who has indeed a safe subsistence, but spends nothing for fine clothes" --

"She threw them at his face," said doleful old Marie Binet sharply. "She had reason. If he treated Jeanne wickedly he now has his reward. She had an amiable appearance, but Mère Pochette clothed her like a doll, and the devil tempted her. She had not the look of a child whom one may believe either good or beautiful," and Marie Binet gazed at her acquaintances for confirmation. This was venturing too far. Marie was known to the initiated to be a thief and a liar, and she feigned not to notice a smile of derision while she took her basket of potatoes and went her way. She had her revenge; at the moment she closed the inhospitable door, and began to mutter a refreshing imprecation, Manon Pochette beckoned and called her eagerly from across the way. The audience within the little shop watched her from the window with envious eyes. Manon Pochette was one who kept her own secrets, she never had been one of the chosen company of gossips.

But this must be a dire emergency, for presently Marie reappeared without her basket. Somebody must go for Father David; the son-in-law had a few moments before slipped from his chair and become a dead weight of insensibility upon the floor; they had borne him to the bed; who could tell whether he might not be dead already?

"Marche! marche!" said Marie importantly, stamping her foot and raising her voice as if her betters were nothing but dilatory horses, and while some one hurried away to find his reverence, the rest followed her over to the Pochette kitchen.

In a few hours more the excitement was over and night had fallen. The young man's face was peaked and white, and his body was lying at its slender length, thin and forsaken of the poor warmth that life had lately kept. Manon was sitting by his side, rocking to and fro and keeping watch by herself. She had lighted some sacred candles which she had long been hoarding, and they were burning at the sleeper's head in the brass candlesticks. The priest had come in time, thank God! the despised son-in-law had opened his eyes and looked around bewildered for a moment. He had assented to, and even welcomed the offices of the church; they must have been to him a last and only provision against the evils that might be waiting for him and his. The baby was christened too; the father had already whispered, with an appealing look, that she was named Manon. Late in the night a waning moon rose solemnly above the level line of the horizon, and looked long at the few white-washed houses with their high roofs. She shone into the eastern windows all along the row. The whole flat country was lying in shadow; this faded moon at last looked into one window that was apart from the rest, as if she had an errand there. Manon was old and tired, she would have no watchers, but she had ceased her prayers and fallen asleep, and the dead man's face wore a look of ineffable peace. The candles were almost burnt out, the poor baby cried sometimes in a faint unexpectant way, and the moon hid herself under the edge of a great cloud.

II.

Out of this nourishing of sorrow and misfortune, like a plant that blooms best in a hard cold soil, grew little Manon. Her childhood was not a pleasant one in its surroundings, indeed a less vigorous nature would have been stunted by the narrow life and lack of sympathy. Bonaventure was a selfish parish in spite of the lovely influence of the old priest, Father David, who, worn out with his service to a stolid flock, at length lay down his terrestrial body to rest in the tawdry burying-ground, while his spiritual body went away to its own inheritance. The new priest had come to the parish half unwittingly; it was a poor cure, and his house and church were plain and uninviting. They could give him no pedestal of worldly pride and power. The new part of the village grew steadily; over at the other side of the railroad there were repair shops and supplies of wood for the trains, and in that quarter Bonaventure expanded itself. The new parishioners were a somewhat lawless set and distinct from the old residents; the little priest was not man enough to control them or to lift them up in the arms of his faith. He moved about among them conscious of the dignity of the church, bland and double, but an inoffensive creature in the main, who wished things were better, but also wished other people to take the trouble of making them so.

Manon Pochette's house was still the last one at that end of the row; she owned a good bit of land just beyond it, and if you crossed that you came to a swamp; the house itself stood a good deal higher, and overlooked the wide country that stretched away to the westward. Behind it was all the eastern country, and from the low ridge there was also a grand view of the railroad that carried idle people to and fro on the face of the earth.

To Manon Pochette's mind the railroad was quite unnecessary except for carrying her wares and her neighbors to the market-town [twon]. As for the passengers, they always seemed the same persons who went to and fro in the hurrying trains, for some foolish reason. She never went into a car herself, the saints defend it, no! She had duties in life, and a vocation, with a piece of land far too large for an old woman to till, and beside, there was the grandchild, who grew like a young fowl, with an unforeseen and impossible appetite into the bargain. The mother, Jeanne, had been no care at all; she had seemed to take care of herself entirely when one compared her with this one, who was a terrible child of desires and eagernesses. All Mère Manon's grievances against the young people had vanished long ago; it was fate that had been hard upon her, not they, and the good Lord had taken them to himself, poor children! Old Manon had said many a prayer for them in the bleak church of a winter morning, and had appeased her conscience by the number of masses she had caused Father David and Father Pierre to say for the good of such innocent souls. Yet occasionally, as she leaned on the heavy hoe to take a minute's rest as she worked among her cabbages, the old Adam in her nature got the better of such pious views of her affliction, and she grumbled to herself about that foolish infant, that ungrateful child, her daughter, or that worthless beggarly heretic, her son-in-law. But she kept their black wooden crosses in good order in the church-yard, and their memories came to her like pale ghosts beside the actual presence and constant demands of her young granddaughter.

III.

Little Manon was made up of puzzles and contradictions; the old peasant woman was more and more distressed and gratified by them day by day. She was glad to have the neighbors see that her grandchild was better than theirs -- in fact she had always maintained a social advantage in Bonaventure corresponding to her residence on the highest point of the ridge. She overlooked Julie Partout and Marie Binet and Mère Poulette disdainfully in more ways than one, but she was exasperated all the same by little Manon's vagaries and differences from her own standard.

The child was devoted to church-going -- she cried when she was very young to go with her grandmother to mass, and her eyes grew large and her face grew grave, when she sat or knelt before the altar and looked at its poor decorations of candles and gilding and the votive offerings of faded artificial flowers and tinsel work that were arranged upon a smaller altar at the side. Poor child, it was not because she was satisfied with this cheap splendor, but rather that she caught the hint it gave of better glories, that she liked to be in church. She gave it no thought, as a bird sings in a cage and praises the bit of sunshine at the garret window, when it has never in all its life spread wings to the current of a great wind or gone swiftly through the bright noonday air to a woodland nest. The grandmother, who knew the human nature of the transplanted Frenchmen and women of her limited Canadian existence; who could tell at once the value of a sheep or even a horse, and the weight of a pig; who was shrewd at gardening and clever at housekeeping; who knew when she was lied to, or when her dearest friend cheated her at a bargain; old Manon, who was never stingy to the priest, or behindhand at her devotions, who thought herself entirely acquainted with things of this world and sure of a respectably high seat in heaven beside, -- this same old Manon was baffled at last and confessed herself unable to understand her granddaughter. The only thing to be said was that Manon the less was made of different stuff.

Sometimes it seemed to the priest, who knew the story of the child's parentage only through the medium of the romancing villagers, that the vigor of the young father and mother had been transferred to little Manon -- that their lives had been checked and blasted to enrich this one descendant. He was given to sentimentalizing a little, was Father Pierre, the parish priest, and he felt a great lack of excitement of the best sort in Bonaventure. Sometimes he told himself that he would see to it that little Manon had some schooling. She should go to the school of the Sacred Heart; she might surely have a year or two first with the good gray nuns; she must not be left to her own devices in this hole of a place. Nobody seemed to know much of the child's father. He had told old Mère Pochette that he had neither brothers nor sisters, but Father Pierre soon discovered that the good woman did not like to be questioned about her son-in-law. She had felt a certain contempt for him because he came from the States; besides, it was indeed a monstrous cowardice that he should have died so miserably and so young, and have made neither place nor fortune for himself in the world. "They should have waited for my consent," old Manon assured herself. "I could not properly hold out always against them if he had been a good man. He was a perfectly stupid pig not to make sure of the wardrobe and dowry he might have been certain I would give to Jeanne. What was my wealth for if not for my one daughter?" she would scold sadly, pulling hard and fast at the weeds; but now it would not be long before young Manon, the little aggravation, would be finding herself a man. But if all the powers of heaven would kindly aid, Manon at least should have a respectable wedding before the high altar, and should drive with her husband and the wedding party as far across the country as the season would allow. Old Manon was herself reared in Quebec, and her hard brown face grew rosy and tender for one moment as she thought of the train of calèches that followed her on her wedding-day. The tall ungainly vehicles; the shouts of the guests; the red-coated soldiers who stopped in the narrow streets to see them pass; the miles of houses and the tall poplars of the Beauport road, -- the thought of it came back with a greater glory year by year. "He was a good man to me from that day," said the widow to herself; "he might have done better than to bring me to this rat-hole and leave me here; but it was a good bit of land and of an enormous cheapness, and he knew that well. If the Lord had pleased to let us remain together, and work in the same world and watch each other grow old, like the rest of the neighbors! It was best so if he must have one of us; a woman can work on the land, but a man is a simpleton in his house. Joseph and Mary aid me with these innocent cabbages that they may hold up their heads; the Lord send us rain, for my poor bones will fail me to bring water to the crops a day longer," and Manon stopped to carefully bless herself as she knelt at her work. Little Manon was of no great use in the garden, and she was frequently berated because she had not been a grandson instead of a granddaughter. She was apt not to be very efficient in the house, but it was not for lack of power or of discretion. She was idle and straying, and liked the fresh air and the sunshine. She was fond of visiting the priest's housekeeper of an afternoon, and sometimes Father Pierre himself beckoned her into his own parlor, and gave her lumps of sugar or well-dried figs from the drawer of his writing-table. She had her mother's beauty and her father's persuasive ways, but when she was in pain or her grandmother scolded her, little Manon grew pale and pinched, and looked as her father did that night he came back defeated and dying to Bonaventure. Old Manon was always particularly aggrieved when she caught this painful, surprising likeness, and began to talk about her own sorrows in a wailing petulant tone that sent the young girl from the house to seek elsewhere for comfort.

IV.

In this village, where the days dragged so slowly, the years had a way of vanishing unaccountably. Old Manon had never succeeded in getting her establishment quite to rights again, after the intrusion of the young engineer and his baby. She had made up her mind that certain changes and arrangements would be necessary, and she was an uncommonly executive person, as everybody knew. Suddenly one became aware that little Manon was grown up, and that there was danger of a lover. She was not old enough nor wise enough to think of such things, but elderly people always say that of girls, as if they themselves had waited for their husbands until the year before. Manon was unexpected in her choice; her grandmother was so conscious of her kinship to an unknown mass of strange, rich, willful, clever, and vagrant foreigners who belonged to the States, that she had vaguely looked forward to the appearance of a hero who should claim Manon's idle hand; a man, however, who had wealth and power, and who would be a son-in-law, indeed! But one spring night the silly girl had come sauntering home later than usual, laughing softly and chattering like a swallow with young Charles Pictou, of whom no one could say anything good. A terror to the schoolmistress, a rebel at home and abroad; a youth who liked nothing but leading his dog through the world, or lounging about the railroad station to see the roaring engines and the gaping strangers. Charles Pictou, indeed! and Manon's light-heartedness was promptly quenched by a vigorous box of her pretty ears as soon as she had entered the house. "Pick these beans, quickly," said the cross old woman. "Am I to die of toil? You would starve like the beasts if I were not here to earn the bread for your foolish mouth." And in that moment a fierce championship arose in little Manon's heart for the lad whose whistle could even then be heard distinctly, as if he were waiting outside, longing to defend her in her distress.

That summer the crops were bad, and

all Canada was poor and complaining. The lumber-yards were

deserted, the rain spoiled the grain, the fishermen were in

distress, and aid was to be sent to them

in the forlorn gulf villages. Once in a

while some enterprising family had gone to the States, and

indefinite rumors of their splendid prosperity had journeyed

back along the straight shining lines of the railroad; but soon

it became a common event, and the old women knitted in their

doorways, and saw the younger neighbors go proudly away to seek

their fortunes. The elder Manon was more contemptuous. "It is

all one, here or there," she said to the priest's housekeeper;

"the good-for-nothing expect to find a country where larks go to

the oven and cook themselves, and apples fall sugared from the

trees." She surveyed the paltry possessions of the emigrants

with pity, and wished their owners good luck with compassion. "I

am one who remains behind," she said stiffly, and shook her head

until her flat black hat shuddered from a sense of its

insecurity.

The autumn shut down dark and rainy; every few days some pale-faced sisters of mercy or of charity, in their quaint out-of-date garb, went flitting from house to house of the Bonaventure settlement, begging alms for the love of Mary and of Jesus, for some sufferers or for the impoverished church. The remote villages were in danger of famine. It was the worst harvest ever known, and in spite of reports that work was hard to find in the States, the trains were fuller than ever of emigrants. Bonaventure was tided over any great distress, in common with most of the railway settlements, but some of its inhabitants thought they were miserable because other people were, and at best life was neither too rich nor too comfortable. In the Western States there were whole farms given away; in the East there were mills where even the children could earn great wages. The little place was in a ferment, the quiet habitants had never been so excited and restless. The old women croaked, they were condemning some persons for going, and others for staying. Father Pierre laid down his mass-books and tried to calm his people, but those who remembered his predecessor spoke often of the benignant presence of Father David, and openly reminded each other of his value to the parish. The fiery French nature began to show itself unpleasantly, and households were divided against themselves.

The gloomy weather continued, the winter drew near. Little Manon and old Manon went their separate ways, for the young girl was disobedient and would not listen to her grandmother's objections and commands. She and Charles Pictou loved each other dearly, and were only wondering how they could manage to marry. He also was an orphan, and the aunt with whom he had lived was but a poor woman, and lately had gone away with her five thin children to the States. Of late years he had helped to support the household, for he earned a bit of money now and then; but now he was growing older and he would work his fingers to the bones for Manon if there were anything to do. He was full of hope, he would have gone away afoot long ago if it had not been for Manon. The grandmother had talked a great deal in these last days about sending her to school at a nunnery in Quebec, and the young girl knew what it meant; she knew, too, that while everybody else was poor there were loose bricks in their chimney that covered shining money. Sometimes she wondered if it would be wrong to steal some of it to give to Charles, so that he might go away to make a home where they could live together. Father Pierre had never liked young Pictou, the lad's shrewd eyes had seen more than was necessary, and lately Charles had stayed away from mass. But as for the housekeeper, she was on Manon's and her lover's side, and sometimes when the priest sat with her grandmother, Manon slipped over to the great house and took revenge in confiding her dear secrets to so kind a friend as old Josephine. Josephine's little room was like a nun's with its bare boards and its worn crucifix, and pictures of various suffering saints. The good soul had once cherished a certainty that she had a vocation, and told Father Pierre that she must join a sisterhood of great sanctity and benevolence, but the priest had persuaded himself and her that she was wrong. He could not imagine where he should supply her place; surely this also was a vocation, and Josephine was a most careful cook. Life in Bonaventure must not become any more difficult.

But in the face of disapproval at home and distress abroad, the young people fairly flaunted their contentment and happiness. They were sure that Charles would somehow get to the States, and that he would soon become able to send for Manon or to come for her. "The old tyrant is right," Charles said magnanimously. "She knows I should be able to take care of you, and so I should indeed. But she might show some confidence in me," and he stamped his foot and twirled the tassel of his raveled red worsted belt.

V.

The sweet sad day came at length, without note or warning. Josephine herself, after scores of prayers and misgivings, had ventured to offer Charles a liberal assistance from her slender savings, and he was off like a falcon, after a few hurried kisses and promises to his sweetheart. He ran to the next station, five miles away, to catch an express train which did not stop at Bonaventure, and the girl with tearful eyes went down to the village, to the place where the street crossed the track, to catch a last glimpse of her lover. She wished that Charles had been able to say a prayer in the church, but she would do that for him. Her woman's heart shrank from the strangeness and dangers which he might meet, but she longed to go with him; she would have braved sorrow and want if she could have gone with him to the States. It seemed very lonely in the old cottage, when she returned; she passed her grandmother, who sat in the doorway looking surly and dismal, without a word. The sky was covered with low-lying gray and silver-white clouds, the black spruce woods stretched away cold and thin to the level horizon. It was almost winter weather, and she was alone and felt unsheltered in that great flat landscape with its threadbare coat. She hoped that she need not go down to the station again for a long time to come. She had not seen Charles on the train, there was such a roar and dustiness as the train rushed by and a crowd of young men; one of those with the red sashes must have been Charles himself; had shouted adieu, or sung noisily. She felt as if every one of them were laughing at her own secret, and hated the strange faces that stared at her for one miserable moment before they were swept out of sight. Charles was a thousand times more skillful than the other lads of Bonaventure; he could surely make his way, but to what temptations might he not yield, and only yesterday they had been together, and separation had seemed almost impossible; at that hour the States had seemed as remote as Heaven.

VI.

Now that Manon's heart had gone away from Canada, she seemed more a foreigner than ever. All her thoughts and hopes had gone to the States with her lover, and the short days seemed long and dreary. In the house she tried to serve her grandmother well, she hardly cared to go out-of-doors at all, and sat near the fire, sewing, or picking beans with a far-away look in her eyes that made her companion more and more angry. They had said nothing to each other about Charles since their first fierce battles earlier in the year. The provincial life was very dull at best. One has only to look at the transplanting of the French peasants, childish, mercurial, and full of traditions and grievances, from their ancient civilization to this untamed wilderness -- only to think of their being carried by a sort of social inertia over the roughness of their changed conditions, to understand the incongruities of Canadian life in the remote settlements. By the time Manon was grown there were few fêtes and but little revelry and amusement of any description. The young men soon hardened into stolid farmers, who discussed the politics of the province and scrutinized the behavior of their English rulers with more or less inapprehension. They grew stupid and heavy; they drank gin and bad beer; some of the wives had a hard time of it, and one would hardly recognize their relationship to the merry vine-growers and soldiers who had been their ancestors. Old Manon Pochette preserved many of the old customs; she was more a French peasant and less a Canadian than her neighbors, but young Manon, who had been seeing life of late through a glamour and dazzle of happiness, sat listlessly in the clean bare cottage, and wished herself away. There was a colored print of a saint with a bleeding heart, which the grandmother had bought from a peddler. Manon had hated it once with its woebegone look, but now she looked to it often for sympathy and companionship. The brass candlesticks still decorated the high shelf above the stove. The same angular chairs and tables which thrifty Joseph Pochette had made himself stood in order around the room.

The chief thing to be hoped for was a letter, but none came from young Pictou; perhaps the noisy company he had joined on the train had beguiled him, and he had already forgotten Bonaventure. He had promised to send a letter to Josephine's care at the priest's house, but presently she was found one day in tears and shook her head dismally when Manon asked the often repeated question. The girl's sharp eyes discovered that some enemy had guessed her simple plot, and went away to pray, not for patience but for vengeance. Later, as she entered the house, she found old Marie Binet warming herself by the stove. The drifts were deep out-of-doors and the girl came in softly enough in her great snow boots, but her grandmother feigned not to hear her. "He was a good-for-nothing" she was grumbling; "he will never return, and at last I have nothing to fear. I had already directed Father Pierre to advance the price of a ticket from me, when that trembling fool Josephine forestalled the plan."

Manon stood on the threshold and the old women quailed at the sight of her angry eyes. "Come in from the snow," growled the mistress of the house, "my old bones ache already, and you will like to see me bent double."

"Another year," and she had quite regained her self-possession, -- "another year and I will go to the shrine of La Bonne Ste. Anne. It will be a pretty tour for thee, too, Manon," she added in a softer tone, but Manon's ears had become deaf. "Another year," she was saying to herself; "I may be dead then, and if not, to go with a groaning procession of cripples! God forbid!" and tears filled Manon's eyes, and even fell down upon the well-scoured floor. "Where is my letter?" she said suddenly, and turned fiercely upon her grandmother.

Old Manon was equal to so slight an occasion. Father Pierre himself was deep in this intrigue, which gave it a certain dignity and value. "Letter!" she repeated, "you never had a letter in your life, and why should I covet it who cannot read even my mass-book? Ungrateful, listen to me! Next year you shall go to Quebec and see fine things; to Lorette church, and to the chapel of the Seminary, where are blessed relics. That is all the world; when one has seen Quebec, one knows everything. I have a little money saved from my poor garden," she added amiably by way of explanation to old Marie, who nodded sagely. "It is something to pray for -- Quebec!" Marie responded devoutly, but the foolish girl would not listen, she was pressing her forehead against the cold window-pane and staring out into the starlit night. What fools she and Charles had been! Of course Father Pierre had taken the letter from the post and given it to her grandmother. Old Manon fairly chuckled with satisfaction, and went on chattering with her guest. After this startling episode, they spoke a quaint dialect, clipping their thin words, and dwelling lightly on the objectionable letters. Such language belonged to the lips and not the heart, one would say who listened and did not understand.

Marie did not mean to stay any longer than she could help; she was too anxious to give herself the pleasure of reporting such a bit of news elsewhere. Some persons would take the lovers' part, and there might be a fine discussion presently, in the little shop across the way. Manon Pochette was in most things a shrewd woman; one cannot tell why she chose to make a confidant of the least reliable of her neighbors.

Manon the younger grew more and more angry that night and longed more and more to find her hoped-for letter. If she could only hold it in her hand, she believed that she could easily wait for daylight and read it aloud then over and over, until she knew it by heart. She lay in bed beside her grandmother with wide open eyes until she heard the familiar long-drawn breaths that belonged to sound sleep. Then she crept out softly, and went like a mouse about the room; she felt in the capacious pocket, in a little box that was under a loose board in the floor. Her heart beat fast as she unwound the long cord that fastened it, but there was no letter anywhere. The old woman was growing deaf lately, and could not have heard such gentle movements, but it seemed a perilous enterprise, and proved to be a disappointing one. If Manon only knew where to write to her lover, or if she only knew how to follow him, it would be enough, but she cried herself to sleep that night and the next night and the next. Before many weeks were spent, Father Pierre went away suddenly and a stranger came to take his place.

VII.

The winter months passed by, there was sickness in the village of Bonaventure, and everybody longed for the spring. Manon had grown thin and pale; she could not eat, she would not smile, her life was spoiled at its outset, and Josephine, who had meant to be a friend to the young people, bewailed her indiscretion and wished that she had tried to keep young Pictou at home. There was plenty of work now at the station; they had even brought some young men from elsewhere, and Charles might have been well established, if only he had gained a little patience. "We that fight for ourselves make enemies of Heaven," she sighed, and tried to make amends with prayers and piteous confessions of her sins. As for the letters, they had long ago been read and laughed over and burnt in the priest's room, and Father Pierre had given old Manon a generous glass of wine. Josephine had seen it through the keyhole. She never told little Manon of that; she would not lower the child's reverence for the priest and for sacred things. Father Pierre had always hated Charles; alas for that poor human nature that even his holy calling could not lift above the earth and its weaknesses.

When Mère Pochette looked at her young housemate, and in spite of herself could not help pitying the dull eyes that had once been so bright, and the faded cheeks, she forgave herself her share in the sad change; for was not she thinking always that every day added something to her possessions, and that by and by she would find a suitable young man, and would go frankly to him and announce the magnitude of little Manon's dowry. All the lads gave shy glances at her, the pretty simpleton! There must be thriving grandsons of her old Quebec acquaintances by this time; she would fling her money east and west at the wedding, and then work on among her vegetables until her time for departure came. "All, yes, she shall have all," the old woman muttered once in a while and blessed herself at the thought.

At last her plans began to take definite shape, since it was plain something must be done. The neighbors need not scowl at her, for was not she meaning to make the long-talked-of journey to Quebec as soon as the first fine weather came, and her garden was made and planted? That would pay Manon for all her fancied grievances, and as the winter waned the glories of that expedition pictured themselves brighter and brighter. Manon should find a rich husband there for a certainty, of a description and with such amiable qualities. She herself would indeed like to see the old city again and those of her friends who were left. Manon would think no more of that foolish, handsome beggar lad who had forgotten her after all; she had nothing else but him to think of in Bonaventure, but in Quebec she would quickly console herself. "For what have I slaved myself all these years?" the old woman would demand angrily of Marie. "I have a right to forbid her marriage with a worthless lad, and I only step in to keep her from her mother's fate -- my good Jeanne, who was thrown away to a vagabond."

But when the early spring came, little Manon had lost her strength and her youthful spirit altogether. She cared nothing for the stories about Quebec, which were at last paraded desperately. She sat all day in the doorway, watching the long trains come across the plain and go away into the dim distance of the north. The clouds of spring hung low, and when sometimes a clear band of light was left above the western horizon, she grew hopeful and gazed at it as if some blessed vision might appear there for her reassurance. It seemed as if the child of misfortune and sorrow must have disappointment for her inheritance. The neighbors scolded to each other about old Manon Pochette's vast wealth, and repeated their conviction over and over that she would soon only have herself to hoard it for, if she did not take care.

One night there came a summons to the grandmother that Father Henri, the new priest, desired her to remain at the church after early mass next morning. Mère Pochette obeyed somewhat unwillingly; she was shy of this stranger, and angry beside that indulgent Father Pierre had been superseded. He had carried more than one of her secrets out of harm's way, that was a comfort; and she did not mean to take another spiritual adviser so far into her confidence.

She left her granddaughter sleeping, and sighed a little as she stood by the bedside looking at the sad face of the young creature who was after all the dearest thing in the world. Once or twice lately the thought had crossed her mind that the first thing to be thought of in Quebec was a good doctor. More than one silly girl had pined away and faded out of this world like the April snow-drifts -- for nothing but love's sake; while if only young Pictou's presence would cure little Manon, nobody knew where to find him. Perhaps Father Pierre would remember, but where was he?

Early mass was over, the sun was well above the horizon, and began to shine warmly into the bare church, and the tarnished finery of the altar glittered and looked quite splendid. It might be that the new priest meant to beg for a great sum of money for the restoration of the church; some one had said he had this much at heart, and Manon's face was black for a moment with resentment. She was truly very anxious now about the sick girl at home. As she knelt at her prayers her thoughts kept wandering homeward instead of to a vague heaven, and a great throne to which the Bonaventure altar was a plaything. What would life be worth if little Manon should die? Such an event would make her own prayers and good works worse than useless, for it was her own short-sightedness that had brought this grief. There were only a few old people left in the church, who had nothing else to do and could take their time at their rosaries; the altar boys had scuffled in the vestry and gone away, leaving their tumbled and torn ecclesiastical raiment on the floor. Father Henri had flushed angrily when he caught sight of them, and quickly opened the door to call the young rascals back, but a moment afterward he gently shut it, and came out into the church tall and slender, with a grave sweet face, stopping to kneel before the altar as he passed before it to where old Manon Pochette seemed to be diligently praying. She was watching him through a narrow crack of her eyelids, but she bowed her head as he approached and pressed the small worn crucifix to her breast. The slender cord broke, the beads separated and fell with a patter like hail upon the floor. "Do not gather them now," said Father Henri hurriedly, but somehow the old woman did not dare to look higher than the frayed hem of his long black gown. It was scant and made of poor material, she observed, and the thought seemed like a reprieve that she would make him a present of a new one at Easter. Easter was late that year, and there would still be time. Josephine would know the proper means to use and the cost of such a benevolence.

She rose to her feet and followed the good man; they made obeisance together side by side as they crossed to the vestry door. The old parishioners regarded this with interest, and wondered what was going to happen, taking counsel of each other in loud whispers as the door was shut. Mère Pochette's heart was quaking; she watched the priest while he picked up the small vestments and half smiled as he heard the owners' merry voices outside. Then he turned and took a letter from his pocket. "I bring good news to you and yours," he said courteously; and Manon the elder, who had feared some dire calamity, -- the loss of her savings or the death of young Pictou for a certainty, -- found herself growing faint and dizzy. "Sit down, my child," said the priest. "You are no doubt fasting. Listen, I will read this letter."

Once to hear such news would have given Manon a fancied foretaste of Heaven; now she heard it without excitement, almost with disappointment. Her poor grandchild's father had been one of a respectable family, and now a sum of money equal to the old Canadian's own fortune had fallen to the poor sick girl at home. The lawyer had been at some trouble to trace the heir. Father Henri volunteered to answer the communication, and with some surprise at the manner in which it had been received he turned away. He had much business on hand that day, there was a visit to be made to a dying person miles away down one of the long muddy roads of Bonaventure parish.

But old Manon had fallen upon her knees; she was weeping sorely and begging for a blessing. She had sinned; she was avaricious and stony-hearted; the good God was punishing her already with the pains of hell, and taking her one treasure to himself.

Father Henri listened with dismay. "I am cursed by this wealth," she groaned, and groveled upon the floor at his feet. He knew that the young girl was ill, but in that bleak country one learns to take such dispensations without surprise; the tender creatures are kindly gathered to the dear saints, and taken up from this blighting and evil world.

"Listen," said Manon Pochette, at last regaining her composure and standing before the priest determinedly. "Listen, you must find for me this Charles Pictou before it is too late. I cannot let this my child die with hatred in her heart toward me. I am an old woman; I have had my way long enough, and it brings me only sorrow and shame. I will send him money. I will treat him as my own son. I will tell him all, for I burnt the letters that he wrote to Manon long ago. If he has taken another in her place, the punishment will be mine." Was this the hard-faced woman who had looked scornfully in even Father Henri's face? He closed his saintly eyes and said a prayer as he stood before her, and raised his hands as if to call down mercy upon the stricken gray head. "I will talk with you this evening," he promised, and they parted silently.

Little Manon had waked and arisen, and presently she crept feebly to the window to watch for her grandmother. She wondered what kept her so long away. The big black hats of the neighbors had reappeared in the short street, and the day was begun as usual. The men were off to their work, and the children were gathering around the schoolhouse. The sun was bright and clear, and the girl felt strengthened and cheered by it. She heard the cars presently; perhaps Charles might yet come back, though she had almost ceased to look for such a happiness. She grew hungry, she became tired with the exertion of crossing the room, she was so weak that the tears began to flow down her thin cheeks. "My grandmother cares nothing for me, nothing," she mourned; "she is bargaining with old Philippe, the gardener; every year she is less generous;" but at that moment Mère Pochette was kneeling in passionate grief at Father Henri's feet in the chilly vestry.

At last she approached, and little Manon was filled with wonder at her look. "You must get well in this good weather," she said; "we will go soon to Quebec, and you shall have the one you love best for company. Forgive me at last, my child," but the sick girl could not comprehend the full meaning of such words, though the speaker stood there appealing, repentant, the square, sensible business woman who could be cheated by no one. And now little Manon rose and put her arms close about the weeping grandmother's neck. Only yesterday faithless Marie Binet had announced that this neck should in the name of justice be encircled by a halter.

The train from the States was just out of sight that very morning -- its long plume of smoke had hardly drifted away in the clear air before a handsome young man came lightly up the street. He did not stop at any of the drinking shops near the station, as most men did, but he hurried toward the older village on the ridge above -- the straight, uniform row of ancient French houses, and from several of these eager eyes followed him to the end of the settlement. Then the various housekeepers rushed out to confer with each other upon the astonishing event of young Charles Pictou's incomprehensible return. It was like unneighborly old Mère Pochette to have sent for him without giving anybody the pleasure of knowing it, but at that moment she was thanking blessed Mary and Joseph, her patron saints, for this miracle straight from the skies. It was seldom at any rate that an emigrant returned so soon. Charles had a prosperous air already, and the whole village was in commotion that morning, while Father Henri was called to a noble feast the moment he returned from his errand of consolation.

The young habitants, who still wore red worsted belts with tassels, looked at their former neighbor's fine clothes with admiration. He was earning good wages with prospect of advance, but he had become too miserable at the strange silence. He was not so very far away, and had taken his first chance to see little Manon again. He had sent letters to prudent Father Pierre, but that worthy had kept silence, being at any rate at a great distance from Bonaventure over seas.

So Manon's strength came back again in this sunshine of happiness, and the lovers presently were married and lived their simple lives together. The world was a comfortable place enough without going to Quebec, but the occasion of Mère Pochette's grandchild's wedding could be marked by nothing less than such a journey, and she saw her children lead their procession of calèches, with immense complacency, living her own youthful joys over again in their behalf, as one returns in autumn to the meadows where one has gathered the flowers of spring.

Old Manon bore a vast bundle when she returned to Bonaventure, and took from it proudly a handsome cassock for Father Henri. The good man was at his devotions, but she gave it to Josephine and lingered for a few moments to have a friendly talk. She had brought Josephine herself a remembrance of less value. "He is a blessed saint, this father," the stayer at home said. "He speaks no harsh word, but goes before us like a holy shepherd!" and the housekeeper blessed herself as devoutly as she could have blessed the priest himself. The ancient holiday maker could not linger; her shrewd eyes had detected a grievous neglect of her young cabbages on the part of their guardian, old Philippe. He had not expected her home so soon, the pig! Presently the round black hat made its appearance among the weeds, a new and imposing great black bonnet having been laid aside, and one would find it hard to believe that Mère Pochette had taken so great a journey.

The neighbors came one by one without fear or reproach and leaned over the railing of the garden. They were all very good-natured, for had not one of their own Bonaventure lads secured the old miser's money after all? The high-roofed white house was lonely that night; the upper casements were wide open, and the color of little Manon's deserted red geraniums could be seen in the bright moonlight. Little Manon herself, rich and happy, had gone away to the States.

NOTES

"Mère Pochette" was originally

published in Harper's Magazine (76:588-597), in March

1888 and collected in The King of Folly Island and Other

People (1888). This text is from The King of Folly

Island (1888). Where I have noticed probable errors in a

text, I have added a correction and indicated the change with

brackets. If you find errors in this text or if you see items

that you believe should be annotated, please communicate with

the site manager.

[ Back ]

seigneur: lord; a landed

proprietor. This term designates a particular system of

settlement used by the French in Canada during the colonial

period. For a brief description, see: B. Young and J. A.

Dickinson, A Short History of Quebec (Toronto, 1988),

pp. 44-47. (Research assistance: Carla Zecher).

[ Back ]

The factor: one who acts as an

agent, as in managing a settlement for a landowner.

[ Back ]

Beauport, in Lorette ... the

French régime: Beauport is now a northeastern suburb of

Quebec City in Canada, on the north bank of the St. Lawrence

River. According to Britannica Online, "In 1634 Robert

Giffard established there one of the first European settlements

in Canada. The name Beauport probably comes from the bay

in the historic province of Brittany in France." Lorette, also

near Quebec City, was a mission settlement for converted members

of the native Huron tribe (see below for more). The French

régime began with colonial settlements in Canada and ended with

the French and Indian War in 1763, when Canada became a British

possession.

[ Back ]

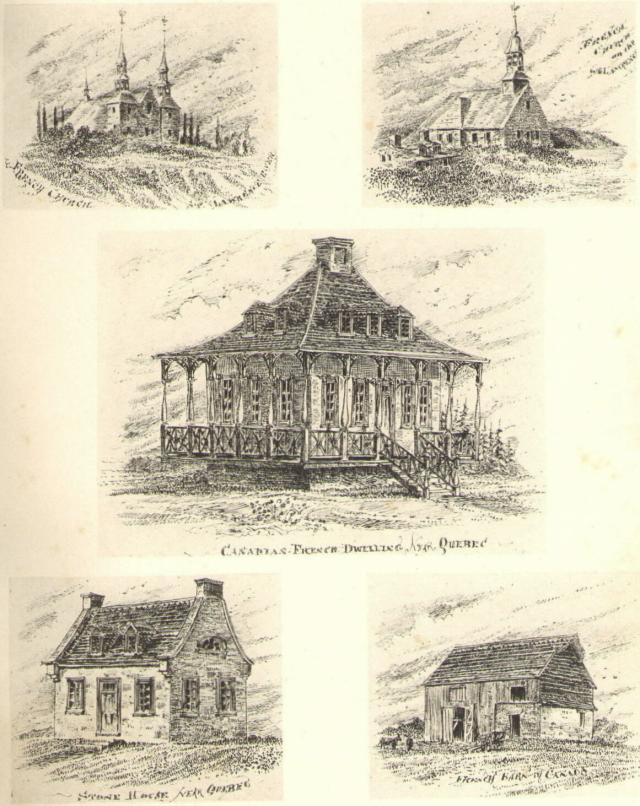

French buildings on the St. Lawrence River:

Two churches, two houses, and a barn.

From Wm. Barry, Pen Sketches of Old Houses, 1874.

Courtesy of Tufts University Library.

Providence: God as active in

the world.

[ Back ]

the States: The United States.

[ Back ]

off their feet: See Matthew

10:14.

[ Back ]

St. Joseph: Joseph was the

husband of Mary, the mother of Jesus.

[ Back ]

the blessed stations of the

cross: "Also called THE WAY OF THE CROSS, a series of

fourteen pictures or carvings portraying events in the Passion

of Christ, from his condemnation by Pontius Pilate to his

entombment. The series of stations is as follows: (1) Jesus is

condemned to death, (2) he is made to bear his cross, (3) he

falls the first time, (4) he meets his mother, (5) Simon of

Cyrene is made to bear the cross, (6) Veronica wipes Jesus's

face, (7) he falls the second time, (8) the women of Jerusalem

weep over Jesus, (9) he falls the third time, (10) he is

stripped of his garments, (11) he is nailed to the cross, (12)

he dies on the cross, (13) he is taken down from the cross, (14)

he is placed in the sepulchre. The images are usually mounted on

the inside walls of a church or chapel but may also be erected

in such places as cemeteries, corridors of hospitals, and

religious houses and on mountainsides." (Source: Britannica

Online).

[ Back ]

the old Adam in her nature: In

Christian doctrine, Christ is sometimes spoken of as the New

Adam, because he undoes the consequences of Adam's fall in the

Garden of Eden (See Genesis 2-3). The old Adam in human nature

would be the tendency to sin that is a consequence of the fall.

See Romans 5:11-19 and I Corinthians 15:22.

[ Back ]

calèches: 2-wheeled, horse-drawn

vehicles with a driver's seat on the splashboard, used in

Quebec. Note that the spelling has been corrected in this text

to the standard modern spelling. In Jewett's text, the word is

spelled, "caléche.">

[ Back ]

the forlorn gulf villages:

Villages along the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

[ Back ]

sisters of mercy or of charity:

The Sisters of Mercy are a Roman Catholic religious congregation

founded in Dublin in 1831 by Catherine Elizabeth McAuley with

the purpose of aiding young girls, providing food and clothing

for the needy, and performing various works of mercy. Sisters of

Charity are "any of numerous Roman Catholic congregations of

noncloistered women who are engaged in a wide variety of active

works, especially teaching and nursing. Many of these

congregations follow a rule of life based on that of St. Vincent

de Paul for the Daughters of Charity .... Several congregations

of the Sisters of Charity in the United States and Canada are

branches of the community founded at Emmitsburg, MD., in 1809 by

Mother Elizabeth Bayley Seton, the first native-born American

canonized saint." (Source: Britannica Online).

[ Back ]

habitants: This text is

inconsistent about placing this French word in italics. I have

left this punctuation as it is in The King of Folly Island.

Though the nuances of this term are quite complex, in Jewett's

day, it would be generally understood to refer to French

Canadians, as opposed to English settlers or natives. (Research

assistance: Carla Zecher).

[ Back ]

fêtes: feast day of a saint in

Catholic and Orthodox churches, celebrated in some countries,

such as France, as one's name day, like a birthday.

[ Back ]

the shrine of La Bonne Ste. Anne:

St. Anne is the mother of St. Mary. The basilica at

Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré remains an important site of pilgrimage

for French-Canadian and other Catholics.

[ Back ]

Lorette church, and to the chapel of the Seminary, where are blessed relics:

Old Lorette and New Lorette, both near old Quebec City, were

mission settlements of the often moved group of converted Huron

natives who were attached to and to some extent protected by the

French in Canada. In each settlement, a chapel was built and

dedicated to Our Lady of Loretto, and modeled after the Holy

House of Loretto, which, Francis Parkman says, "as all the world

knows, is the house wherein Saint Joseph dwelt with his virgin

spouse, and which angels bore through the air from the Holy Land

to Italy, where it remains an object of pilgrimage to this day"

(536). Parkman reports the story of the miraculous building of

the chapel at Old Lorette, which afterwards became a popular

object of pilgrimage. When the settlement was moved to New

Lorette, another chapel was built. (Source: Francis Parkman, The

Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century, Part

Second. Boston: Little, Brown, 1930). It is unclear which of

these Mère Pochette intends to visit.

The Seminary in Quebec, founded by

Monsignor de Laval in 1663, is the oldest educational

institution in Canada. It provided elementary education during

the French régime. The priests and teachers who came to the

Seminary brought with them objects of devotion that led to the

Seminary housing perhaps the most important collection of holy

relics after St. Peter's in Rome. Among the relics Mère Pochette

may have hoped to see were a small stick from the Garden (or

Mount) of Olives and a piece of stone from the cave of the

nativity of the Holy Virgin in Jerusalem. (Research assistance:

Betty Rogers and Carla Zecher).

[ Back ]

the cars: railroad passenger

cars.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, assisted by Carla Zecher, Coe College.