| Main Content

& Search Jewett Letters - Contents Letter Texts Introduction Preface |

SARAH ORNE JEWETT

LETTERS

["]Good letters," says Lytton Strachey in Characters and Commentaries, "are like pearls; they are admirable in themselves, but their value is infinitely enhanced when there is a string of them…. What makes a correspondence fascinating is the cumulative effect of slow, gradual day-to-day development - the long leisurely unfolding of a character and a life." The letters of Sarah Orne Jewett gathered herein illustrate the point perfectly. No one in itself may be classified as exceptional; each contributes its tiny glimmer. But out of the totality emerges a sure sense of the variegated personality and experiences of Maine's foremost literary lady, constituting a vital complement to her published works.

At maturity Miss Jewett was tall and ample, her full figure and stately carriage imparting a hint of her natural dignity. She had lustrous brown eyes and an abundance of black hair modestly arrayed. Her face, with its fine forehead and strong chin, inclined to squareness, and by most would be counted handsome. Mary Ellen Chase, Ellery Sedgwick, Helen M. Winslow, and Harriet Prescott Spofford concur on the term beautiful, but one suspects that they are remembering the piquant smile and artless magnanimity that suffused her countenance when she addressed herself to anyone, of whatever age or station. Belying the soft benevolence of her inner nature were the somber clothes she consistently wore, usually black or navy blue skirt and jacket relieved by a scant glimpse of white shirtwaist. Her eyeglasses hung around her neck or were attached to her lapel by a black ribbon.

Miss Jewett's most patent characteristic was simplicity. The epithets Whittier applied to Deephaven -- "so simple, pure, and so true," -- might as aptly have been applied to Miss Jewett herself. There was no archness in her. Answering the doorbell at 148 Charles Street on sophisticated Beacon Hill she would say disarmingly, "I am a country person." She was at ease with children and treated them with especial kindness and humor, "one of the family visitors that we [children] were always glad to see arrive." She never lost the feeling for youth's enigmas and ecstasies. "This is my birthday," she wrote to Sara Norton in 1897, "and I am always nine years old." And she was humble. Once, at the height of her reputation, she remarked to Mary Cabot Wheelwright, "You know, I seem impressive, but really I only come up to my own shoulder."

This was the combination of qualities that entranced the literati of large cities, this sturdy good sense and supple sensitivity that informed her temperament and found its way into every line she wrote. "She was really a great and charming person," says Mildred Howells. "Miss Jewett was like a princess," echoes Elizabeth McCracken. Even Tennyson, a formidable hermit in his later years, succumbed to her attractions after he sourly admitted her to his presence. But Miss Jewett was not all sunbeams and dewdrops. Opposed to her habitual complaisance there lay within her a stubborn small core reserved against intrusion. She respected the privacy of her own thoughts and person, and could insist upon it staunchly when pressed. Miss Jewett was pleasant and receptive, but she was not to be put upon.

As might be expected of a correspondence spanning four decades, the stationery is of many sizes, shades, and textures. Miss Jewett used most frequently the conventional folio (one fold, four pages), but at times turned to varying numbers of single sheets. In the 1880s and sporadically thereafter, SOUTH BERWICK, MAINE is embossed at the head. Around this designation - above, over, below, on either side or both - she affixed some form of date. She usually carried sufficient paper and envelopes in her extensive movements about New England, for she often drew a line through the printed heading and substituted her address of the moment. More than once when her stationery gave out, she blithely effaced her hostess' letterhead and filled in her own. She observed the propriety of black-bordered paper whenever it pertained to her.

Miss Jewett wrote rapidly and spontaneously, without too great forethought. Nevertheless, her handwriting is sturdy, with few furbelows and no distracting slant. There are some illegibilities, but they do not puzzle for long. Her letters of the last two or three years show noticeable loss of vigor and distinctness, words slumping into each other with seeming lack of strength to stand alone; her lifelong habit had been to link words, but this is different. In compliance with current epistolary vogue she wrote vertically across dateline, salutation, and opening lines after she had exhausted her four pages. Sometimes, in lieu of this, she continued along the margins, inserting hasty last words into the veriest inch that offered itself. She crossed out expressions, injected carets, and superscribed freely. When afterthoughts flashed and space was available, she disregarded the formality of postscript, merely appending the additional messages below her signature. She signed variously, depending upon the sex of the correspondent, the degree of friendship, or the nature of the note.

She was nonchalant about dating. As like as not, she might limit herself starkly to the name of the day - Friday; she might indicate the time of day - Monday morning, Wednesday afternoon; she might inscribe as much as the date and month - 12 June; and (editor's bane!) she might with classic forbearance put down nothing at all. She capitalized and abbreviated to suit her fancy, intensely relished the ampersand, ignored apostrophes, and employed the dash as jack of all trades - as comma, period, and signal for new paragraph. She punctuated capriciously, forgot the second parenthesis, paired single with double quotation marks. Now and again she misspelled, most commonly in the suffix, when her mind had already darted ahead to the next word or phrase. She barred her l's instead of t's and jumbled tenses. The titles of books, periodicals, newspapers, poems, stories, and articles she rendered with carefree inconsistency. She confused dates of publication and, in at least one instance, misquoted herself.*

These peccadilloes are obviously evinced not to disparage Miss Jewett but to emphasize the fundamental role that letters played in her life. Miss Jewett's generation was brought up to look upon letter-writing as an amenity and a responsibility. In that era of chronic peregrination, it was deemed indispensable to keep one's family up on one's activities; so letters were long and chatty. It was also regarded a rudeness not to attend to one's business mail promptly and graciously; so letters were fairly frequent. Upon a person of far-reaching family attachments and sundry occupational interests, this could impose a substantial expenditure of time. Miss Jewett's conscience and inclination nudged her into inveterate morning sessions of correspondence, a predominantly agreeable, but occasionally tedious chore. She strove without complaint to discharger her obligation. Moreover, it was imperative to hurry, since afternoons and evenings were allocated to writing for publication. It is no wonder that lapses of this sort recurred in her letters.

She wrote in relaxed, workaday prose; only her notes to Violet Paget here contain conscious literary touches. She concerned herself with the commonplace, propounding observations and attitudes lightly, without pretension. Constantly she displays the same eagerness "to know the deep pleasures of simple things, and to be interested in the lives of people around me" that brought instant success to her train of books from Deephaven to The Countryof the Pointed Firs. In these letters lie discoverable the rhythm and the flavor of Miss Jewett's daily round of living, exhibited coolly, gaily, enthusiastically, thoughtfully, affectionately. And the last, perhaps, most prominent: Miss Jewett effused affection in a manner basic and ingenuous.

Her domestic letters are typically energetic, newsy, and pointed toward the recipient's specific tastes. She divulges chitchat about vacations, excursions, ailments, and neighbors' "doins"; shares items from friends' notes to her; accepts and offers condolences. She is beguiled by the botanical beauties of Maine, exults over its terrain and vistas, considers soberly its social and industrial revolution, and is somewhat snide about her local nativity. Here and there she intersperses odd bits of lingo encountered in her wayfaring.

Outside of the immediate family circle one finds a profusion of "bread-and-butter" notes to her hospitable friends. She inquires about their wives or husbands, dotes exceedingly on their children, refers them to worthy new publications, and takes sides without belligerence in timely public controversies. She congratulates writers of her acquaintance on their latest appearances in print, makes appointments for luncheons, arranges for lectures, rejects committee memberships, and helps promote community projects.

Attainment of maturity can be traced through her business relations with editors. Initially she reveals herself as a shy child tremulously entertaining literary ambitions. She unsheathes her heart to her first important sympathetic editor, apologizing for her paucity of education and enterprise, explaining her reasons for secrecy, and asking elementary questions about copyright. As she gains in experience, a more confident tone asserts itself. She discusses details of titles, proofs, and publicity, often insisting upon her own judgment in such matters. She suggests or weighs possibilities for sketches and collections, recommends her friends' writings to editors, and felicitates the latter when they are promoted or turn out exceptionally good issues. She talks terms professionally but does not drive a bargain. Miss Jewett knew what she was worth at contemporary rates and calmly asked for it. She had no need to haggle; her prosperous grandfather had left the family financially independent.

Miss Jewett did not write reviews or publish extended critiques on authors but she is voluble about books, stories, poems, and the art of writing in her letters. Indeed, if one is to form an opinion about her literary distinctions and valuations, he has no other recourse for information. She reported regularly on her voluminous reading, signifying unselfconsciously her approval or reservations. She pondered the nuances of theme and style, analyzed her own methods and schedule of production, and solicited criticisms of individual pieces or passages. She commented upon the merits and shortcomings of her work to editors, friends, and appreciative readers - including children. She was liberal with advice and encouragement to prospective authors, taking time she could poorly spare to initiate them into the mysteries of conceiving, producing, and selling.

Conspicuous in these letters are several paragraphs which Miss Jewett strongly paraphrased and used as bases for subsequent stories or articles. Although she seldom put her letters to ulterior service, she was not totally opposed to seeking good notices through influential friends or through her uncle, a newspaper editor. She was far from aggressive, however. Almost without exception she referred to her fictional creations modestly, even timorously.

So, in mosaic fashion, out of a welter of matching facets, evolves the portrait of a lady. Miss Jewett's catalogue of attributes, perceptible in her public writings, becomes more strikingly manifest in these private disclosures. The luminous heart, the discriminating ideals, the profound compassion, and the uncomplicated vision tremble closer to the surface in these unguarded, unaffected personal testaments. For the more formal occasions, Miss Jewett chose her habiliments with utmost care. Here she appears in casual apparel.

RICHARD CARY

Waterville, Maine

*Note

In order to facilitate reading,

and in some cases to clarify Miss Jewett's meaning, most of

these careless or idiosyncratic usages have been

conventionalized, notably her datelines, salutations and

valedictions, paragraphing, and titles of publications. Her

ubiquitous dashes and exclamation points have been retained

where they seem to serve a rhetorical purpose. Fragmentary dates

have been supplemented and missing dates have adduced -

sometimes certainly, sometimes speculatively - from internal or

other valid evidence.

ABOUT twelve miles inland from Portsmouth, the confluent Piscataqua and Salmon Falls rivers meet the tidewater and form a majestic stream. Just above this point, behind a sloping screen of riverside pines and willows, lies the town of South Berwick. Here, on September 3, 1849, within earshot of the clamorous falls, was born Maine's most representative writer, Theodora Sarah Orne Jewett, impressively named after her paternal grandfather and grandmother.

The white clapboard house she was born in reflected both the general influence of colonial tradition and the personal history of her titillating grandfather, Captain Theodore Furber Jewett. Two-and-a-half stories high, with hip roof and dormer windows, it was built in 1774 by a John Haggins (or Higgins) and purchased some sixty years later by Captain Jewett when he retired from the sea and moved his family up from Portsmouth. A Doric portico with fluted columns, and a massive front door with raised panels and iron arrowhead hinges, face the town square. A similar door at the opposite end of the hall leads into the garden. Three ships' carpenters reputedly worked a hundred days to complete the wood carving in the deep center hall, which is bisected at the ceiling by a slender arch. On its way to the floor above, the regal staircase pauses at an intermediate landing. Under the large pulpit window of flowered glass which illuminates the recessed seat here, Miss Jewett spent numberless hours of reading and meditation.

The elegant tracery, fireplaces, furniture, and accessories in the house indicate the level of comfort and refinement to which the Jewetts were accustomed. From Bristol and Le Havre came gleaming mahogany four-post bedsteads, Adam mirrors, Chippendale chairs and tables, Wedgwood candlestick holders, a beautifully turned spinet, and Swiss hand-embroidered curtains. An exotic flair is vouched for in the prevalence of Chinese vases and foreign wallpapers, particularly the ornate paper in the guest room -- gigantic red velvet arabesques on a pink and white background. Originally intended for the manor house of an island governor in the West Indies, it had been taken as prize from a French vessel by an American privateer, brought into Salem, and there procured by Captain Jewett. As if to compensate for this outlandish vivacity, walls throughout the house supported shelves of august leather-bound books and framed samplers featuring homiletic verses.

In the spacious garden and yards surrounded by a fence of white pales grew several varieties of trees: pear and apple for fruit, immense elms for shade, and a grand file of poplars for beauty. Lilac bushes flourished out of hand; larkspur, honeysuckle, lilies, and pink hollyhocks jostled each other in transient patterns of color.

In this province of racing water and vibrant meadows Sarah Orne Jewett grew up. Gradually she attained intimacy with the flora she was to describe so lovingly in her sketches. In a state of muted enchantment she courted the odors of sweet fern, wild rose, and balsam. She quested for blueberries and strawberries in season; learned the lineaments of bittersweet, chicory, mallows, and marsh rosemary, whose spume-like lavender flowers never failed to grip her heart. She mused upon the flight of brilliant insects, coveted a glimpse of the hermit thrush, and became so enamored of nature as to dub herself "first cousin to the caterpillar," "sister to a giddy-minded bobolink."

There were other excitements. She investigated the sprawling salmon fishery on the fringe of the river; stared wonderingly at farmhouses with blank windows, locked doors, and overgrown paths; poked about forsaken cellarholes and ancient cemeteries; ventured fearfully into silent orchards floating wanly in sea-mist. In the house, the guest room presented a fascinating narrow door which opened onto a hidden staircase that wound from cellar to attic. When that palled there was always the playroom in the barn, with the foresail of some forgotten schooner spread over the floor. In her grandfather's fabulous general store she attended breathlessly the strange stories unrolled by sailors, merchants, and upcountry rustics who came to barter.

Her greatest delight was to take protracted "rides and drives and tramps and voyages" along country lanes and coastal settlements. At first she had no awareness of either watching or listening. She took no deliberate interest in the quaint remnants of Indian and English customs, nor in the surviving oddities of phrase and accent, except to notice that older natives pronounced Berwick Barvik, in the Norse fashion, instead of Berrik, after the English preference. She made no calculated study of regional mores or characters, apparently satisfied that differences existed between the commercial Yankee, the moribund gentility, and the homely Irish and French Canadians.

As to formal education, she confessed to "instant drooping" whenever confronted by the drab walls of a schoolroom. She appeared at the outset to have an aversion to book learning, and parried her father's efforts to interest her in Sterne, Fielding, Smollett, and Cervantes. She berated herself as "a heedless little girl given far more to dreams than to accuracy."

Who is to chart the metabolism of an artist -- the incessant bombardment of impressions on the sensitive child consciousness, the unwitting absorption, the infinitesimal slow growth of understanding, the fumbling urge toward expression? All these impinged upon the deeper reaches of young Sarah's psyche, moiling fretfully, making vague imprints, causing sudden turnabouts. At one moment, visible ignorance of the value and influence of her environment; at the next, firm appreciation of "the quiet village life, the dull routine of farming or mill life." At one moment, active resistance to mature suggestions about reading; at the next, active pleasure in the works of Jane Austen, George Eliot, and Mrs. Oliphant realized through the importunities of mother and grandmother. Who can measure the ultimate force of her physician-father, whose gentle perseverance plucked at so many responsive strings? And how is one to appraise reliably the effect of companionship with her redoubtable grandfather William Perry, "The Old Doctor" of Exeter, who seemed to combine felicitously the qualities of seer and spur? But for that rare, irascible gentleman, the faltering girl might never have left off dreaming.

Whatever the chemistry, and to some degree in spite of herself, Sarah Orne Jewett came to possess an impeccable sense of time and place and people. By late adolescence she was capable of imbibing and projecting the subtlest details of ambiance with delicacy and fidelity. While still a child she had begun tentatively to set down her thoughts. In the beginning she wrote only in verse; prose was such a problem that the mere announcement of a school composition left her in tremors. With the passage of time she found rhyming more difficult and prose more pliable, so she bent her will to mastering this "enticing" medium. She spent rapturous afternoons in the family garret among yellowing records and mementoes. She was to be seen through the window of her room, scribbling early and late at her favorite slant-top desk, to which she had earnestly pinned Flaubert's dictum: AÉcrire la vie ordinaire comme on écrit l'histoire." Happily, she discovered that her sympathies and her themes tended toward the bucolic characters and landscapes of her beloved Berwick precinct. She formulated a literary creed which, long after, she revealed in the Boston Journal: "When I was, perhaps, fifteen, the first 'city boarders' began to make their appearance near Berwick; and the way they misconstrued the country people and made game of their peculiarities fired me with indignation. I determined to teach the world that country people were not the awkward, ignorant set those persons seemed to think. I wanted the world to know their grand, simple lives; and so far as I had a mission, when I first began to write, I think that was it." It became the shibboleth by which she lived and wrote faithfully for more than four decades.

In 1868 her prose and verse were published for the first time in magazines of broad circulation. Before she was twenty, the Atlantic Monthly accepted one of her stories. The letters assembled in this volume commence shortly thereafter and range to the year before she died.

1877 DEEPHAVEN (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co.)

1878 PLAY DAYS (Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co.)

1879 OLD FRIENDS AND NEW (Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co.)

1881 COUNTRY BY-WAYS (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1884 THE MATE OF THE DAYLIGHT, AND FRIENDS ASHORE (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1884 A COUNTRY DOCTOR (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1885 A MARSH ISLAND (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1886 A WHITE HERON AND OTHER STORIES (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1887 THE STORY OF THE NORMANS (New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons)

1888 THE KING OF FOLLY ISLAND AND OTHER PEOPLE (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1890 BETTY LEICESTER (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1890 TALES OF NEW ENGLAND (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1890 STRANGERS AND WAYFARERS (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1893 A NATIVE OF WINBY AND OTHER TALES (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1894 BETTY LEICESTER'S ENGLISH XMAS (Baltimore: Privately printed for Bryn Mawr School)

1895 THE LIFE OF NANCY (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1896 THE COUNTRY OF THE POINTED FIRS (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1899 THE QUEEN'S TWIN AND OTHER STORIES (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1901 THE TORY LOVER (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

1905 AN EMPTY PURSE (Boston: Merrymount Press)

1911 LETTERS OF SARAH ORNE JEWETT (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.) Edited by Annie Fields.

1916 VERSES (Boston: Merrymount Press) Edited by M. A. DeWolfe Howe.

Copyright 1967 by Colby College.

This text is reprinted by permission of

Colby College and may not be reprinted in whole or in part

without written permission from Colby College.

The Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project is grateful for permission from the following libraries and archives to reprint individual letters in this collection. These letters may not be reprinted without permission from these institutions. Furthermore, all letters in this collection may be subject to the Copyright Law, Title 17, U.S. Code.

Sarah Orne Jewett Papers, George J.

Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin

College Library.

The following

letters by number: 10, 13-16, 66, 97, 101, 113, 116, 121, 126,

135.

Colby College Special Collections,

Waterville, Maine.

Unless

otherwise specified, all of the letters in this collection are

held by Colby College Special Collections.

Fales Library & Special

Collections, New York University.

Sarah Orne

Jewett to Maria H. Bray, March 1, 1888.

Newton High

School, Newton, MA.

Professor Cary

indicates below that he obtained permission from Newton High

School to publish Jewett's letters to Samuel Thurber. Though

the school is no longer able to locate these letters, it would

be courteous to notify the school of any intention to reprint

them.

Western Reserve

Historical Society, Case Western University.

Sarah

Orne Jewett to Gertrude V. Wickham, August 29, 1886

Of the one hundred forty-two letters included in this volume, one hundred and twenty-five are in the Edwin Arlington Robinson Memorial Room at Colby College Library, and seventeen from other institutions were published for the first time, wholly or in part, in the Colby Library Quarterly. For permission to print the latter I am indebted to Bowdoin College for the Gilman family letters, to Newton (Mass.) High School for the Samuel Thurber letters, to the Fales Library in New York University for the Maria H. Bray letter, and to the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland for the Gertrude V. Wickham letter.

In addition to the names cited in the first edition of this work (Colby College Press, 1956), I wish to express my obligation to the following who have contributed to this augmented version.

For donating Jewett letters to the Colby collection: Rosamond Thaxter, Elizabeth C. Field, Mrs. Frances Dudly Shepard, Joseph W. P. Frost, and the Colby Library Associates.

For permission to quote from unpublished materials: Harvard College Library, and the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

For providing specific data or making useful sources available: primarily Dr. John Eldridge Frost, Librarian of New York University, who has more intimate knowledge of the life of Sarah Orne Jewett than anyone anywhere; Elizabeth Hayes Goodwin, resident hostess of the Jewett Memorial House in South Berwick; my colleagues, Professor Archille H. Biron and Kenneth P. Blake, Jr., Librarian of Colby College; also Mrs. William C. Beale, Jacob Blanck, Christina Carlow, Mrs. Josephine Carter, Lee Coyle, Joseph W. P. Frost, Mrs. Mayna B. Guptill, Clare C. Hardy, Carolyn Jakeman, Robert H. Land, George P. Nye, Mrs. Frances Dudley Shepard, Rosamond Thaxter, Rose Weinberg, and scores of dedicated staff members in the dozens of libraries I quested.

To any individual I may have omitted, my apology and sincerest thanks.

Once more, because it is so appropriate, I offer this passage from Boswell's Advertisement to the First Edition of The Life of Samuel Johnson: "Where I to detail the books which I have consulted, and the inquiries which I have found it necessary to make by various channels, I should probably be thought ridiculously ostentatious. Let me only observe, as a specimen of my trouble, that I have sometimes been obliged to run half over London, in order to fix a date correctly; which, when I had accomplished, I well knew would obtain me no praise, though a failure would have been to my discredit."

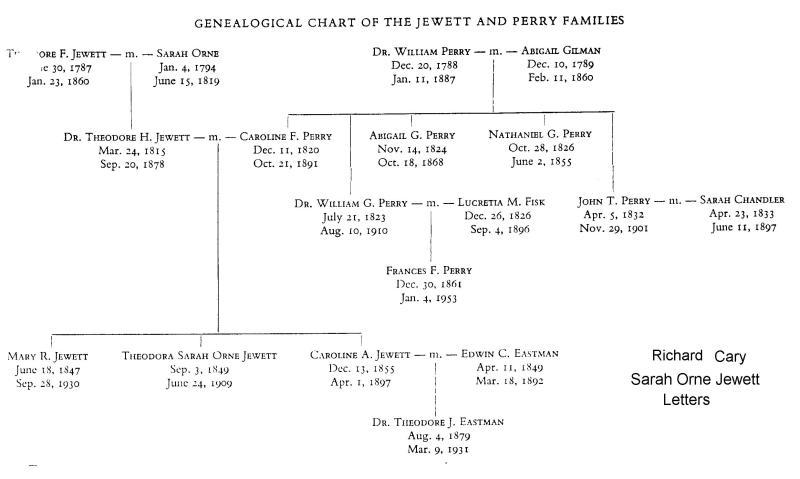

To obviate continuous repetition of

dates in the editorial text, a chronological list of BOOKS BY

SARAH ORNE JEWETT has been provided on page 9, and a

GENEALOGICAL CHART OF THE JEWETT AND PERRY FAMILIES on page 174.

[ This edition of Cary's work places

the list of books and the genealogy on this page.]

| Main Content

& Search Jewett Letters - Contents Letter Texts Introduction Preface |