Sarah Orne Jewett to Mellen Chamberlain

WHEN his friend Charles Bell wrote Mellen Chamberlain on July 8, 1874, regarding an impending visit from the latter, neither could foresee the outcome. But Bell foreshadowed it when he described other guests Chamberlain might expect to find on hand. "Sometime next week," he reported, "we expect our party to be increased in numbers by the arrival of three young ladies, whom you have never seen, but with whom I have no doubt you will be much pleased."

Chamberlain's annual visit with Bell and his wife at their summer home, "The Cove," at Little Boar's Head in North Hampton on the New Hampshire shore, was for many years a focal point of the season. The friendship between the two men was a warm one. Not only had they been roommates together at Dartmouth, in the class of 1844, but they also shared closely many interests. Both were lawyers and public figures: Chamberlain was at this time a judge of the Boston Municipal Court; Bell, later Governor of the state, had already become prominent in the New Hampshire legislature. Even stronger links were their collections of American historical manuscripts, their research and writings on early New England history.

Of the three young ladies whom Chamberlain was to meet in the summer of 1874 one became a friend of long standing: no less a person than Sarah Orne Jewett, whose short stories won the admiration of Henry James for their "elegance and exactness," an estimate which the tides of taste have not altered. At this time only twenty-five years old, her first story had been published in the Atlantic Monthly five years before. The other two ladies were her sisters Mary and Caroline. That the Jewett girls were guests of the Bells was due no doubt to ties of kinship, and with the town of Exeter, where the Bells made their winter home. Charles Bell's first wife had been a Miss Sarah Almira Gilman of Exeter and a cousin of the Jewett girls' mother. And they provided companionship, one may infer, for the Bells' daughters, Mary and Persis.

The success of Chamberlain's visit with the Bells that July is reflected in letters preserved in his personal correspondence now in the Boston Public Library. His hostess, writing on August 4 to acknowledge the gift of a Prescott autograph,* remarked, "Do you suppose when we have been six years finding out your accomplishments, we shall not need the visit of at least six years more to really get acquainted with you?" Mary Jewett, on August 5, thanking him for a photograph of himself, added her appreciation for the pleasure he gave during their stay at "The Cove." The stimulus provided by the young ladies appears to have made Chamberlain particularly expansive, and revealed genial aspects of his character which a holiday from home -- his wife remained in Chelsea -- may have heightened.

Thus the friendship between Chamberlain and Miss Jewett began. The group of letters, also in the Library, which she later wrote him shows her spontaneity, her warmth, her accurate observation of people and of nature, and her sense of humor.

The first, written from her family home in South Berwick, Maine, on August 5, 1874, reflects a mutual interest in autograph collecting --, a penchant Miss Jewett was later to share with her friend Annie Fields:

Thank you for the autographs and for your letter which came yesterday. You were very kind to me, and I don't believe it possible that you enjoyed the week at the Cove as much or have been as homesick since you went away as I! I have thought of one thing after another that you could have explained to me, but then it was not good by [sic] for always and I like to think I shall see you again before very long. And I must say here it was very good of you not to send all the autographs! I think you have been very generous already however.

The next day but one after I saw you I had a telegram from some friends and went in a hurry to join them at Wells beach where I stayed until Monday night. To-day our friend Anna Fox is to come, and I wanted a day or two before this to myself; for I had any quantity of letters to write, and wished to have a slight "house-cleaning" of my desk and get somewhat "straightened out."

Mary came home last night and after I brought her from the station I had the jolliest of horseback rides. I wish you had been with me: indeed I have wished for you again and again. You must surely come to Berwick! I must say goodbye now, but may I write to you sometimes? Not a "debt and credit correspondence" for I don't wish to impose upon so busy a man, but I shall like to think I may ask you questions and "be friends."

I venture to send my regards to Mrs. Chamberlain as I think we are sure to be friends one of these days and there must be a beginning to everything!

From a subsequent letter of the 27th it is apparent that Chamberlain did find it possible to pay a visit to South Berwick around the middle of August. What he can have written to occasion Miss Jewett's comments, it is difficult to surmise. Can it be that, at the age of fifty-three, he found her patently innocent friendliness disconcerting?

I hope you do not think I am rude not to have answered your note before, or at least to have acknowledged the receipt of the autographs which were most gratifying. I hope, now that I have settled down at home that I shall find an opportunity for making a more definite plan of my collection than I have had hitherto.

I have not told you yet what I wish to say at the very first: that your letter was delayed as I was down at the seashore, and that since it came I have either not felt in the mood for writing or have not had a chance. I have just looked your letter over and though it seems unaffectedly kind and interested, it seems to me, that, as in the first reading, I do not quite catch your meaning, that you had some purpose in writing it and were somehow puzzled about our having known each other. I am very glad if I have given you pleasure, for you have been so kind to me, and I am never apt to forget a friend. Besides this, I am, as you know wishing most heartily to do my work better and to learn as fast as possible and you cannot doubt that I am ready to take all the help I find. And when this help is given me so kindly and cordially as you have given it, it is all the pleasanter and better for me. I appreciate your friendship most heartily. I do not know that my saying this answers you satisfactorily, but I may understand you better by and by.

I am writing in a hurry this afternoon for I have little time to myself as we have some visitors and I am continually on the wing. I had a charming week at the beach, indeed I do not know when I have been happier. I had a friend with me whom I am very fond of, and it is not very often I get one of my cronies all to myself. I think I have not written you since that pleasant day you gave us. I enjoyed it very much and hope it will not be the last. It was so nice to have you like Berwick so much. I hope to have a very satisfactory autumn. I like it best of all the year and I mean to do just as much as possible. Thank you for saying I may write you and ask you questions as much as I please. That is a great privilege.

A month later, on September 29, Miss Jewett took advantage of Chamberlain's permission to consult him, reporting at the same time on relatives and friends:

Will you tell me sometime where I can find out something about "Roger Bacon"?* I know very little, and don't know where to find more. I have been very busy since I wrote you last, and instead of having been hard at work at my "writing" I have been driving with Father, and enjoying the friends who have been visiting us. Two or three have been my especial cronies, so you will know I have been happy! The two Aunt Marys will be here next week I think and after them Helen and Persis [Bell], and don't you think that (to quote from one of our favorite Rye Ballads) "five of them will be foolish"?* I am sure it will be a very "good time" -- I have not had much time for study, though I have begun German and music lessons, and am reading Chambers' Cyclopedia.* I have always read it, but never consecutively and I think this will teach me much more than any amount of disconnected reading.

I don't have a great deal of time to myself but I shall by and by. There is no one in the parlor but Father who is taking his after-dinner nap so I can give you no messages. I hope you are well and I am sure you are enjoying this fine weather.

The friendship thus begun in 1874 was no mere summer's encounter, for in a letter of April 9 of the following year, written on her return from a visit to Boston, Miss Jewett refers to seeing Chamberlain on an earlier trip: he appears to have taken her to the Boston Athenaeum.* The actress who occasioned the recent trip was the famous Italian, Adelaide Ristori; the plays, Giacometti's Marie Antoinette and Schiller's Mary Stuart:*

I have been in Boston again since my long visit. It was last week and I only stayed two or three days. I went down to see Ristori and I enjoyed her most heartily. I saw her play Marie Antoinette and Mary Stuart. The first play was almost unbearably sad and though I didn't take refuge in tears like my neighbors, I was a day or two "getting over it." I thought of you and Mrs. Chamberlain while I was in the city but I had little time and did not see half my friends.

I was so glad to hear through Helen Bell that you are "going abroad." I am sure you will enjoy it so much, and you may be certain that I send you my best wishes. I hope you will have a splendid time and that your plans may all come true, or else something better happen in their places. I hope to go some day myself, but the older I grow, the longer I am content to wait, for I wish to know more than I do now about what I am going to see. I am sorry that you will not be one of the party at "the Cove" this summer. I shall miss you there, but "good times" rarely repeat themselves I find, and so I am always sorry to have any pleasure come to an end for though I hope for other good things, it is a little sad to have to say goodbye to any one good time in particular. I often think of: "In every end there is also a beginning."* I associate it with "On the Heights"* but I have a doubt just now as I write whether I found it there or somewhere else.

As for my collection of Autographs it grows slowly. Mrs. Waterston gave me a charming note of Mr. Longfellow's when I was in Boston and Miss Quincy* has promised to save some for me. I find that I grow more interested in them, and yet it is better fun to get them than it is to have them.

I must say goodbye now. Please give my kindest regards to Mrs. Chamberlain. If the family knew I am writing they would add some messages I am sure. If you have time while you are gone I should be gladder than ever to hear from you. I went to the Atheneum [sic] the other day with Father and remembered our sojourn there with great pleasure. Father was much edified by my wisdom!

With the best wishes for your journeys . . .

Chamberlain sailed for Europe in late April, 1875, to spend six months there. Within ten days after his arrival at Queenstown he appears to have written to Miss Jewett from Killarney. Her reply, dated May 30, portrays her at her epistolary best:

I think you were very kind to write to me so soon, and I enjoyed your letter exceedingly. I am so glad that your sight-seeing has begun so charmingly and your letter made me wish I could be in Killarney too. Though I am in no hurry to "go abroad" for I think the longer I wait, the more I shall enjoy it and besides, there is still so much to be seen and done at home. I am still a stranger to many charming things in this little country-town of mine and it is more beautiful this spring than ever before. I have been boating a great deal and I wish you could go with me "down river." The other night I took a basket with me and put ashore wherever I pleased -- for it was high tide -- and dug fern and columbine roots, and picked anemones and violets, and then, after it was too dark for that, I rowed up river a long distance and let my boat drift down again. There was a little of an exquisite sunset left, and the birds were going to sleep and the air was sweet with the smell of willows and wild cherry blossoms. I think it would all have been as pleasant to you as it was to me.

I must tell you something about my work as well as my play, and first, I have finished a continuation of "The Shore-house"* which perhaps you remember. I worked very hard on it and was a little tired at the last, and expected a letter of criticism in two or three weeks, so it was "ever so nice" to have a note from Mr. Howells in less than two days, beginning with "Your paper is perfectly charming" and saying also "You have an uncommon feeling for talk. I hear your people" -- and some other charming "remarks." So I was goodnatured for several days, and I was all the better pleased because I felt I had tried to earn the praise. I am getting on slowly now with some other sketches, but I have many interruptions and sometimes I am sadly puzzled, not liking to neglect either my writing or the other things and something must be crowded out. Gardening and driving with Father and studying and sewing and visitors cannot be put off or ignored oftentimes and so the writing has to wait -- and I often feel very sorry, for the ideas and plans that come into my head are like the dreams which are clear enough when one first wakes in the morning, but which are faded out and forgotten by noon.

I am glad you liked the verses in the Atlantic.* I do not remember however, that you said you liked them! I suppose I guessed at it from your telling me that you read them over more than once. You are right in saying that somebody would read between the lines: they were written once when I was thinking of one of my "cronies" in Boston of whom I am very fond; but I have not confessed this to anybody but the person herself. I have innocently answered when people asked if they were for any one in particular, that they would do for several of my friends -- as the Pope sends encyclical letters to the bishops! It is somewhat true -- that answer, but not strictly, so you must keep the secret.

What do you suppose I have for a bouquet on my desk? I have just looked up and saw them: a big bunch of dandelions. I'm so fond of them, and I believe on reflection, that there is no other flower I like so well. They bring back my childhood so vividly, if indeed I need to have it brought back, when it seems to me sometimes I never have lost it! It has been hard for me to get used to being grown up.

I wonder if I have anything to tell you in the way of news? I never have very much to tell. My letters seem to be made up of chatter about myself. We are to have Helen and Persis Bell here as soon as they are through with a fair which is to come off in Exeter. May Gilman was here with another small cousin of mine two or three weeks ago, and I enjoyed her more than ever. We condoled with each other tenderly because you were not to be at the Cove, and I am sure we shall miss you very much indeed. I wonder where you are? I think you must be somewhere in England and I hope you are enjoying yourself most heartily. Thank you again for writing to me for it was a real pleasure to hear from you. The family would wish to be remembered to you if they knew I was writing ...

During their visit to "The Cove" that summer the Jewett girls joined other guests in an omnibus letter to Chamberlain. Sarah's contribution was a poem referring to a relative, a Mrs. Willard, known as "Aunt Long." She introduces her lines:

I feel that you will deeply sympathize in the feelings I have tried to express in the enclosed Lament, and send it, thinking it will be more interesting than any other addition to this letter. I hope you are enjoying yourself particularly. We have missed you very much.

Whether or not Chamberlain's sense of humor was equal to the poem we shall never know.

A Lament

Tune, Hamburg.*

The tides creep slowly in and out,

The sea winds blow; the wild birds call;

Oh sweet and bright the wild rose blooms –

There is a shadow o'er them all.

Oh, what to us the rose's bloom?

How can we care for sea-birds' song?

Through tears we watch the restless sea

For absent is our dear Aunt Long.

We loved to sit upon the rocks;

To watch the waves and dashing spray,

But sigh, for she, who oft last year

Was spattered with us, is away.

No more we raise our voices sweet

To that melodious darkey tune,--

There's no Aunt Long to serenade,

And useless is the fair new moon.

Her grave behavior; solemn looks;

The hat she wore of ample size

Sweet reminiscences by scores,

Fond memory shows to mournful eyes.

Oh, "Herring" wails and "Gusty" howls,

And Mary fadeth like a leaf.

Persis and Sary, pale and thin

No longer eat, for deepest grief.

The elders strive to hide their grief --

Her namesake steals away to cry;

The afternoons are spent in tears,

And unavailing misery.

Her call on Thursday only served

To make our sadness still more deep.

It passed as quick as swallow's flight,

Or pleasing vision seen in sleep.

The roses fade upon our cheeks,

And hushed is mirthful shout and song.

We mourn beside the sad sea waves,

The absence of our dear Aunt Long.

In the summer of 1876 the Bells themselves went to Europe, and there were no visits to "The Cove." In fact, it is not until a decade later that we find Miss Jewett again writing to Chamberlain. In the interval, following the appearance in 1877 of her volume of stories, Deephaven, she had become one of the leading writers of New England, and the friend of Lowell and Whittier and, indeed, of the whole Boston literary circle. Chamberlain, in turn, had become the Librarian of the Boston Public Library, and as such she wrote to him from South Berwick on June 9, 1886, in connection with her The Story of the Normans, published in the following year:

Do you think that I could have one of the students desks at the Library next week to look over some books about Normandy etc? I have been doing one of the "Stories of the Nations" series for the Putnams in N. Y. and meant to have it done long ago, but I was sick all the latter part of the winter. Now I must hurry and it would save so much time if I could have the rest of the books I want in a nice heap instead of getting them here with more or less difficulty.

Will it give you too much trouble to tell me who [sic] I shall go to at the Library to ask about the books, etc. I want particularly to see the plates from the Bayeux tapestry (there are some edited by Bruce I believe) and Cotman's Architectural Antiquities of Normandy.*

But I will not trouble you with the whole list now.

I hope that you and Mrs. Chamberlain are well. It seems a long time since we had a meeting at the Cove! ...

In the following year the death of Mrs. Chamberlain brought a brief note written, from the home of Mrs. James T. Fields in Charles Street, on May 1st:

I was much shocked to see the notice of Mrs. Chamberlain's death for I did not know that she had been ill. At such a time your friends can only offer their sympathy and dare to say little else but I hope that you will let me tell you how sorry I am for your great loss and sorrow ...

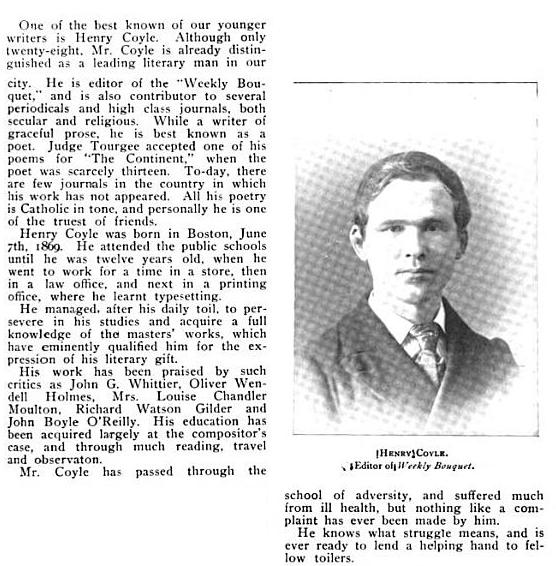

It is again to Chamberlain as a librarian that we find an undated letter, likewise addressed from Mrs. Field's home, regarding a young Irish-American whom the two ladies wished to befriend, named Henry Coyle.* Nothing appears to have come of their efforts, but Coyle himself achieved a worthy career in Catholic publishing and charitable circles in Boston, in addition to publishing several volumes of poetry:

Mrs. Fields has just come up stairs to me to ask if I will not write this note for her to you about a young man who has come to her for help. He has done some very good work in verse and considering his youth, shows a touch of real promise but the poor fellow is so beaten back by illness and poverty that he is in a sad way. His disabilities hinder him in what he is trying to make of himself as a compositor. Mrs. Fields thinks that you may know of something to recommend to him in library channels familiar to you, where his acquaintance with books and his carefulness with his pen may be of use. He spoke of you gratefully in answer to her mention of your name, as "a kind and approachable man" -- so that we are following our own instinct in sending him to you. We shall try to do what we can for him too.

I wish that we might sometimes see you. I have not been in town this winter however except for some brief visits.

By now an established author with some fifteen volumes from her pen -- that classic of New England life, The Country of the Pointed Firs, was to appear in the following year -- Miss Jewett again visited the Boston Public Library in the fall of 1895 - Chamberlain had resigned as Librarian in 1890, but a note to him from his successor, Herbert Putnam, of October 25, refers to her researches there on John Paul Jones.* Chamberlain's own efforts to see her at this time are revealed in a note she wrote him from South Berwick on November 1, 1895:

I have just received your very kind note at the moment when you will be waiting for me at the Library. I came home some days ago and I thought that I told Mr. Putnam and Mr. Knapp [the Keeper of Bates Hall] that I should only be working at the Library for two or three days -- but even if I did there is no reason why they should have charged their minds with remembering it!

I am so sorry that you should have had the trouble of going to the room and being kept waiting, all to no purpose.

I shall not be in town again before the middle of the month; perhaps I can write you then and ask if I may come some day when you are to be at your Library room at any rate ? . . .

In late 1898 Chamberlain published his John Adams and Other Essays, sending a copy to Miss Jewett which she acknowledged on February 2, 1899, from Charles Street. The letter provides a fitting epilogue to their friendship, for Chamberlain, already a sick man, had not much longer to live, dying in 1900:

I thank you very much for your most kind remembrance and for giving me this copy of your book of essays. I will not say that it is a new book to me for I saw it very soon after it was published, but I am delighted to have such a gift from you and I shall always take it in my hands with great pleasure. I often say to myself when I think that it is a long time since I saw or heard from an old friend "Well: my stories are a sort of long letter, they tell what I have been thinking, or, if not, what I have been doing." And so it is when I have a book from a friend himself. Perhaps our books: our essays and our stories tell more than our letters could!

I suppose it was some such feeling that came into my mind this morning when you spoke so kindly of my last sketch in the Atlantic.* You were a very kind friend many years ago when I was beginning to take my work of writing seriously and I like to remember that kindness and interest, and to find that you still feel it in these days when so much of my work is put behind me. I wish that it had been better, but I have done the best I could, perhaps, with a kind of health that was never very certain, or very favorable to steady industry. But my heart has always been in my stories, and I feel sometimes as if I just began to see what 1 could really do.

I have thought many times that I should like to see you again and to talk a little about the things for which we both care. I am much pleased to know that my friend Miss [Louise Imogen] Guiney* is to have something to do with the cataloguing of your collections [of manuscripts] at the Public Library. She is one of our few really distinguished scholars among women, and a devoted student of literature. I am sure that the work will be welcome to her.

With my best thanks for your book and your note . . .

On this note the correspondence closes. If the letters are not numerous, they mirror none the less those qualities which assure Miss Jewett a permanent place in American literature, and portray her in transition from a young woman, somewhat uncertain of herself, into a mature, considerate, and gracious person whose writings are the rewarding reflection of her self.

Editor's Notes

This essay originally appeared in Boston

Public Library Quarterly 9 (1957): 86-96. It is

reprinted here courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public

Library/Rare Books.

a Prescott autograph: It is probable that Jewett had received an autograph of the American historian, William Hickling Prescott (1796 - 1859), since Chamberlain was a collector of American historical materials.

Roger Bacon: Wikipedia says: "Roger Bacon (1214-c.1292), OFM … was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empirical methods. He is sometimes credited (mainly since the nineteenth century) as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method inspired by Aristotle and later scholars such as the Arab or Persian scientist Alhazen. However, more recent re-evaluations emphasize that he was essentially a medieval thinker, with much of his 'experimental' knowledge obtained from books, in the scholastic tradition."

one of our favorite Rye Ballads … "five

of them will be foolish": Rye

is a beach town in Rockingham Country, New Hampshire. It

seems likely Jewett refers to a gospel hymn by George

F. Root, "Too

Late: And five of them were Foolish." The hymn is

based on Alfred,

Lord Tennyson's poem, "Late,

Late, so Late." Both derive from the Parable

of the Ten Virgins, or the Parable of the Wise and

Foolish Virgins, which Jesus tells in Matthew 25:1-13,

Chambers' Cyclopedia:

Chambers' Cyclopedia, according to Wikipedia,

was one of the first general encyclopedias to appear in

English (1728, with numerous later editions and revisions).

Boston Athenaeum .. Adelaide Ristori;

... Giacometti's Marie Antoinette and

Schiller's Mary Stuart:

Wikipedia

says the Boston Athenaeum "is one of the oldest independent

libraries in the United States. ...The institution was founded

in 1807 by the Anthology Club of Boston, Massachusetts.It is

located at 10 1/2 Beacon Street on Beacon Hill."

Adelaide

Ristori (1822-1906) was a distinguished Italian

tragedienne. Wikipedia show illustrations of Ristori in

her roles as Marie Antoinette and Mary Stuart.

Paolo

Giacometti (1816–1882) was an Italian dramatist.

In The World's Progress (1896), William

C. King says that Ristori first brought Giacometti's Marie

Antionette to New York in 1867. She

returned with this play and others to New York in 1875 for a

nine-month tour of the United States. A playbill

from the Boston Globe Theatre indicates that she performed

there in early April of 1875.

Friedrich

Schiller's Mary

Stuart is a verse tragedy telling the story of

Mary, Queen of Scots.

Mrs. Waterston ... Mr. Longfellow's ... Miss Quincy:

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) was an American poet, perhaps best remembered for his long narrative poems such as The Song of Hiawatha (1855). He was probably the best-known and most respected American poet of the nineteenth century. Jewett, through Annie Fields, eventually became friends with his daughter, Alice.

Among Longfellow's correspondents was the Rev. Robert Cassie Waterston (1812-1893), who also corresponded with Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was married to the poet Anna C. Quincy, daughter of Josiah Quincy III.

The Quincy family was prominent in Boston in the 19th century; notable among Jewett's contemporaries and likely acquaintances was the lawyer poet Josiah Phillips Quincy (1829-1910) who became mayor of Boston (1895-1899). It seems likely that the "Miss Quincy" who might give interesting autographs to Jewett in 1875 would be Eliza Susan Quincy (1798-1884), the artist and author, the oldest sister of Anna C. Quincy, but this is by no means certain.

"The Shore-house": "The Shore House" appeared in Atlantic Monthly (32:358-368), September 1873. Jewett reworked it and incorporated it into Deephaven (1877).

the verses in the Atlantic: "Together" first appeared in Atlantic Monthly (35:590) May 1875.

Tune: Hamburg: The hymn tune "Hamburg," is credited to Lowell Mason (1824). Perhaps the most familiar hymn sung to this tune is "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross" (1707) by Isaac Watts.

the Bayeux tapestry ... edited by Bruce ... Cotman's Architectural Antiquities of Normandy: The Bayeux Tapestry Elucidated by John Collingwood Bruce appeared in 1856. Architectural Antiquities of Normandy by John Sell Cotman appeared in 1822.

Henry Coyle: Biographical

information about the poet, Henry Coyle, seems scanty.

The following biographical sketch appears in Donahoe's

Magazine 39 (1898) pp. 74-5.

WorldCat gives his birth year as 1865 and lists the following publications:

The

Promise of Morning (poems, 1899)

Our Church, Her Children and Institutions (1908).

(Link

to Volume 1 of 3)

Lyrics of Faith and Hope (poems, 1913)

This biographical sketch appears in The

Poets of Ireland (1891) p. 85.

COYLE, HENRY. -- The Promise of Morning,

poems, Boston, Mass., 1899.

Born at Boston, Mass., June 7, 1867. His father was a

Connaught man, and his mother from Limerick. He is

self-educated, and has written frequently for American

journals, including verse for Harper's Bazaar, Detroit

Free Press, Boston Transcript, Catholic

Union and Times (Buffalo), and Boston Pilot. Is

now assistant-editor of Orphan's Bouquet, Boston, of

which James Riley {q.v.) is editor.

Further and more

consistent information would be welcome.

John Paul Jones: Jewett at this time was working on The Tory Lover (1901), in which John Paul Jones is a featured character. Jones (1747-1792) was a captain in the American revolutionary navy.

my last sketch in the Atlantic:

Jewett's only story to appear in Atlantic during

1898-9 and before her letter was "The

Queen's Twin," which was in the February 1899 volume.

Louise Imogen Guiney: Louise

Imogen Guiney (1861 1920) was an American poet, essayist

and editor, born in Roxbury, Massachusetts.