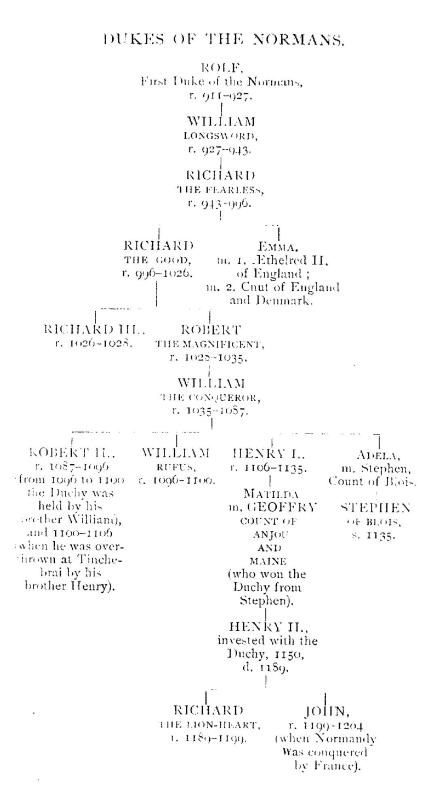

The Normans

by Sarah Orne Jewett

Chapter I

THE MEN OF THE DRAGON SHIPS.

"Far as the breeze can bear, the billows foam,

Survey our empire and behold our home." -- Byron.

The gulf stream flows so near to the southern coast of Norway, and to the Orkneys and Western Islands, that their climate is much less severe than might be supposed. Yet no one can help wondering why they were formerly so much more populous than now, and why the people who came westward even so long ago as the great Aryan migration, did not persist in turning aside to the more fertile countries that lay farther southward. In spite of all their disadvantages, the Scandinavian peninsula, and the sterile islands of the northern seas, were inhabited by men and women whose enterprise and intelligence ranked them above their neighbors.

Now, with the modern ease of travel and transportation, these poorer countries can be supplied from other parts of the world. And though the summers of Norway are misty and dark and short, and it is difficult to raise even a little hay on the bits of meadow among the rocky mountain slopes, commerce can make up for all deficiencies. In early times there was no commerce except that carried on by the pirates -- if we may dignify their undertakings by such a respectable name, -- and it was hardly possible to make a living from the soil alone. The sand dunes of Denmark and the cliffs of Norway alike gave little encouragement to tillers of the ground, yet, in defiance of all our ideas of successful colonization, when the people of these countries left them, it was at first only to form new settlements in such places as Iceland, or the Faroë or Orkney islands and stormiest Hebrides. But it does not take us long to discover that the ancient Northmen were not farmers, but hunters and fishermen. It had grown more and more difficult to find food along the rivers and broad grassy wastes of inland Europe, and pushing westward they had at last reached the place where they could live beside waters that swarmed with fish and among hills that sheltered plenty of game.

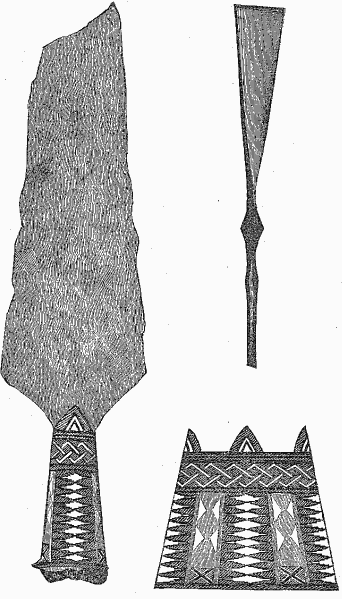

Besides this they had been obliged not only to make the long journey by slow degrees, but to fight their way and to dispossess the people who were already established. There is very little known of these earlier dwellers in the east and north of Europe, except that they were short of stature and dark-skinned, that they were cave dwellers, and, in successive stages of development, used stone and bronze and iron tools and weapons. Many relics of their home-life and of their warfare have been discovered and preserved in museums, and there are evidences of the descent of a small proportion of modern Europeans from that remote ancestry. The Basques of the north of Spain speak a different language and wear a different look from any of the surrounding people, and even in Great Britain there are some survivors of an older race of humanity, which the fairer-haired Celts of Southern Europe and Teutons of Northern Europe have never been able in the great natural war of races to wholly exterminate and supplant. Many changes and minglings of the inhabitants of these countries, long establishment of certain tribes, and favorable or unfavorable conditions of existence have made the nations of Europe differ widely from each other at the present day, but they are believed to have come from a common stock, and certain words of the Sanscrit language can be found repeated not only in Persian and Indian speech to-day, but in English and Greek and Latin and German, and many dialects that have been formed from these.

The tribes that settled in the North grew in time to have many peculiarities of their own, and as their countries grew more and more populous, they needed more things that could not easily be had, and a fashion of plundering their neighbors began to prevail. Men were still more or less beasts of prey. Invaders must be kept out, and at last much of the industry of Scandinavia was connected with the carrying on of an almost universal fighting and marauding. Ships must be built, and there must be endless supplies of armor and weapons. Stones were easily collected for missiles or made fit for arrows and spear-heads, and metals were worked with great care. In Norway and Sweden were the best places to find all these, and if the Northmen planned to fight a great battle, they had to transport a huge quantity of stones, iron, and bronze. It is easy to see why one day's battle was almost always decisive in ancient times, for supplies could not be quickly forwarded from point to point, and after the arrows were all shot and the conquered were chased off the field, they had no further means of offence except a hand-to-hand fight with those who had won the right to pick up the fallen spears at their leisure. So, too, an unexpected invasion was likely to prove successful; it was a work of time to get ready for a battle, and when the Northmen swooped down upon some shore town of Britain or Gaul, the unlucky citizens were at their mercy. And while the Northmen had fish and game and were mighty hunters, and their rocks and mines helped forward their warlike enterprises, so the forests supplied them with ship timber, and they gained renown as sailors wherever their fame extended.

There was a great difference, however, between the manner of life in Norway and that of England or France. The Norwegian stone, however useful for arrow-heads or axes, was not fit for building purposes. There is hardly any clay there, either, to make bricks with, so that wood had usually been the only material for houses. In the Southern countries there had always been rude castles in which the people could shelter themselves, but the Northmen could build no castles that a torch could not destroy. They trusted much more to their ships than to their houses, and some of their great captains disdained to live on shore at all.

|

Top right Iron chisel found in Aamot Parish Oesterdalen. Left from p. 5. |

There is something refreshing in the stories of old Norse life; of its simplicity and freedom and childish zest. An old writer says that they had "a hankering after pomp and pageantry," and by means of this they came at last to doing things decently and in order, and to setting the fashions for the rest of Europe. There was considerable dignity in the manner of every-day life and housekeeping. Their houses were often very large, even two hundred feet long, with the flaring fires on a pavement in the middle of the floor, and the beds built next the walls on three sides, sometimes hidden by wide tapestries or foreign cloth that had been brought home in the viking ships. In front of the beds were benches where each man had his seat and footstool, with his armor and weapons hung high on the wall above. The master of the house had a high seat on the north side in the middle of a long bench; opposite was another bench for guests and strangers, while the women sat on the third side. The roof was high, there were a few windows in it, and those were covered by thin skins and let in but little light. The smoke escaped through openings in the carved, soot-blackened roof, and though in later times the rich men's houses were more like villages, because they made groups of smaller buildings for store-houses, for guest-rooms, or for workshops all around, still, the idea of this primitive great hall or living-room has not even yet been lost. The later copies of it in England and France that still remain are most interesting; but what a fine sight it must have been at night when the great fires blazed and the warriors sat on their benches in solemn order, and the skalds recited their long sagas, of the host's own bravery or the valiant deeds of his ancestors! Hospitality was almost made chief among the virtues. There was a Norwegian woman named Geirrid who went from Heligoland to Iceland and settled there. She built her house directly across the public road, and used to sit in the doorway on a little bench and invite all travellers to come in and refresh themselves from a table that always stood ready, spread with food. She was not the only one, either, who gave herself up to such an exaggerated idea of the duties of a housekeeper.

When a distinguished company of guests was present, the pleasures of the evening were made more important. Listening to the sagas was the best entertainment that could be offered. "These productions were of very ancient origin and entirely foreign to those countries where the Latin language prevailed. They had little or nothing to do with either chronology or general history; but were limited to the traditions of some heroic families, relating their deeds and adventures in a style that was always simple and sometimes poetic. These compositions, in verse or prose, were the fruit of a wild Northern genius. They were evolved without models, and disappeared at last without imitations; and it is most remarkable that in the island of Iceland, of which the name alone is sufficient hint of its frightful climate, and where the very name of poet has almost become a wonder, -- in this very island the skalds (poets) have produced innumerable sagas and other compositions during a space of time which covers the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries."*

The court poets or those attached to great families were most important persons, and were treated with great respect and honor. No doubt, they often fell into the dangers of either flattery or scandal, but they were noted for their simple truthfulness. We cannot help feeling such an atmosphere in those sagas that still exist, but the world has always been very indulgent towards poetry that captivates the imagination. Doubtless, nobody expected that a skald should always limit himself to the part of a literal narrator. They were the makers and keepers of legends and literature in their own peculiar form of history, and as to worldly position, ranked much higher than the later minstrels and troubadours or trouvères who wandered about France.

When we remember the scarcity and value of parchment even in the Christianized countries of the South, it is a great wonder that so many sagas were written down and preserved; while there must have been a vast number of others that existed only in tradition and in the memories of those who learned them in each generation.

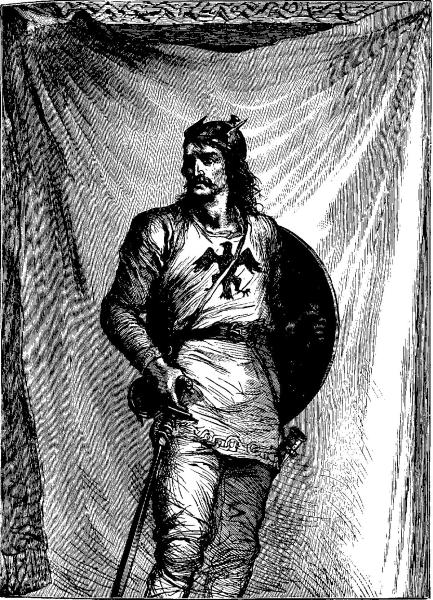

If we try to get the story of the Northmen from the French or British chronicler, it is one long, dreary complaint of their barbarous customs and their heathen religion. In England the monks, shut up in their monasteries, could find nothing bad enough to say about the marauders who ravaged the shores of the country and did so much mischief. If we believe them, we shall mistake the Norwegians and their companions for wild beasts and heathen savages. We must read what was written in their own language, and then we shall have more respect for the vikings and sea-kings, always distinguishing between these two; for, while any peasant who wished could be a viking -- a sea-robber -- a sea-king was a king indeed, and must be connected with the royal race of the country. He received the title of king by right as soon as he took command of a ship's crew, though he need not have any land or kingdom. Vikings were merely pirates; they might be peasants and vikings by turn, and won their name from the inlets, the viks or wicks, where they harbored their ships. A sea-king must be a viking, but naturally very few of the vikings were sea-kings.

When we turn from the monks' records, written in Latin, to the accounts given of themselves by the Northmen, in their own languages, we are surprised enough to find how these ferocious pagans, these merciless men, who burnt the Southern churches and villages, and plundered and killed those of the inhabitants whom they did not drag away into slavery, -- how these Northmen really surpassed their enemies in literature, as much as in military achievements. Their laws and government, their history and poetry and social customs, were better than those of the Anglo-Saxons and the Franks.

If we stop to think about this, we see that it would be impossible for a few hundred men to land from their great row-boats and subdue wide tracts of country unless they were superior in mental power, and gifted with astonishing quickness and bravery. The great leaders of armies are not those who can lift the heaviest weights or strike the hardest blow, but those who have the mind to plan and to organize and discipline and, above all, to persevere and be ready to take a dangerous risk. The countries to the southward were tamed and spiritless, and bound down by church influence and superstition until they had lost the energy and even the intellectual power of their ancestors five centuries back. The Roman Empire had helped to change the Englishmen and many of the Frenchmen of that time into a population of slaves and laborers, with no property in the soil, nothing to fight for but their own lives.

The viking had rights in his own country, and knew what it was to enjoy those rights; if he could win more land, he would know how to govern it, and he knew what he was fighting for and meant to win. If we wonder why all this energy was spent on the high seas, and in strange countries, there are two answers: first, that fighting was the natural employment of the men, and that no right could be held that could not be defended; but beside this, one form of their energy was showing itself at home in rude attempts at literature. It is surprising enough to find that both the quality and the quantity of the old sagas far surpass all that can be found of either Latin or English writing of that time in England. These sagas are all in the familiar tongue, so that everybody could understand them, and be amused or taught by them. They were not meant only for the monks and the people who lived in cloisters. The legends of their ancestors' beauty or bravery belonged to every man alike, and that made the Norwegians one nation of men, working and sympathizing with each other -- not a mere herd of individuals.

The more that we know of the Northmen, the more we are convinced how superior they were in their knowledge of the useful arts to the people whom they conquered. There is a legend that when Charlemagne, in the ninth century, saw some pirate ships cruising in the Mediterranean, along the shores of which they had at last found their way, he covered his face and burst into tears. He was not so much afraid of their cruelty and barbarism as of their civilization. Nobody knew better that none of the Christian countries under his rule had ships or men that could make such a daring voyage. He knew that they were skilful workers in wood and iron, and had learned to be rope-makers and weavers; that they could make casks for their supply of drinking-water, and understood how to prepare food for their long cruises. All their swords and spears and bow-strings had to be made and kept in good condition, and sheltered from the sea-spray.

It is interesting to remember that the Northmen's fleets were not like a royal navy, though the king could claim the use of all the war-ships when he needed them for the country's service. They were fitted out by anybody who chose, private adventurers and peasants, all along the rocky shores. They were not very grand affairs for the most part, but they were all seaworthy, and must have had a good deal of room for stowing all the things that were to be carried, beside the vikings themselves. Sometimes there were transport vessels to take the arms and the food and bring back the plunder. Perhaps most of the peasants' boats were only thirty or forty feet long, but when we remember how many hundreds used to put to sea after the small crops were planted every summer, we cannot help knowing that there were a great many men who knew how to build strong ships in Norway, and how to fit them out sufficiently well, and man them and fight in them afterward. You never hear of any fleets being fitted out in the French and English harbors equalling these in numbers or efficiency.

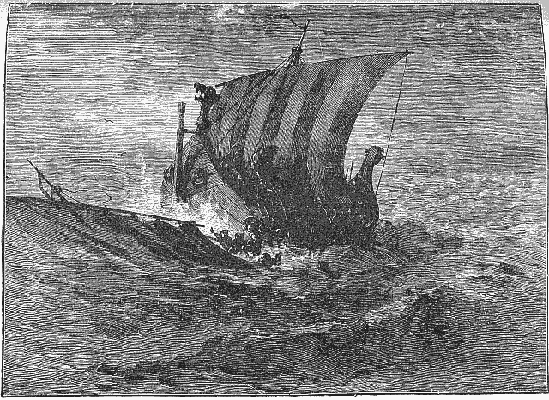

When we picture the famous sea-kings' ships to ourselves, we do not wonder that the Northmen were so proud of them, or that the skalds were never tired of recounting their glories. There were two kinds of vessels: the last-ships, that carried cargoes; and the long-ships, or ships-of-war. Listen to the splendors of the "Long Serpent," which was the largest ship ever built in Norway. A dragon-ship, to begin with, because all the long ships had a dragon for a figure-head, except the smallest of them, which were called cutters, and only carried ten or twenty rowers on a side. The "Long Serpent" had thirty-four rowers' benches on a side, and she was a hundred and eleven feet long. Over the sides were hung the shining red and white shields of the vikings, the gilded dragon's head towered high at the prow, and of the stern a gilded tail went curling off over the head of the steersman. Then, from the long body, the heavy oars swept forward and back through the water, the double thirty-four of them, and as it came down the fiord, the "Long Serpent" must have looked like some enormous centipede creeping out of its den on an awful errand, and heading out across the rough water toward its prey.

Viking Ship, p. 13.

The crew used to sleep on the deck, and ship-tents were necessary for shelter. There was no deep hold or comfortable cabin, for the ships were built so that they could be easily hauled up on a sloping beach. They had sails, and these were often made of gay colors, or striped with red and blue and white cloths, and a great many years later than this we hear of a crusader waiting long for a fair wind at the Straits of the Dardanelles, so that he could set all his fine sails, and look splendid as he went by the foreign shores.

To-day in Bergen harbor, in Norway, you are likely to see at least one or two Norland ships that belong to the great fleet that bring down furs and dried fish every year from Hammerfest and Trondhjem and the North Cape. They do not carry the red and white shields, or rows of long oars, but they are built with high prow and stern, and spread a great square brown sail. You are tempted to think that a belated company of vikings has just come into port after a long cruise. These descendants of the long-ships and the last-ships look little like peaceful merchantmen, as they go floating solemnly along the calm waters of the Bergen-fiord.

The voyages were often disastrous in spite of much clever seamanship. They knew nothing of the mariner's compass, and found their way chiefly by the aid of the stars -- inconstant pilots enough on such foggy, stormy seas. They carried birds too, oftenest ravens, and used to let them loose and follow them toward the nearest land. The black raven was the vikings' favorite symbol for their flags, and familiar enough it became in other harbors than their own. They were bold, hardy fellows, and held fast to a rude code of honor and rank of knighthood. To join the most renowned company of vikings in Harold Haarfager's time, it was necessary that the champion should lift a great stone that lay before the king's door, as first proof that he was worth initiating. We are gravely told that this stone could not be moved by the strength of twelve ordinary men.

They were obliged to take oath that they would not capture women and children, or seek refuge during a tempest, or stop to dress their wounds before a battle was over. Sometimes they were possessed by a strange madness, caused either by a frenzy of rivalry and the wild excitement of their rude sports or by intoxicating liquors or drugs, when they foamed at the mouth and danced wildly about, swallowing burning coals, uprooting the very rocks and trees, destroying their own property, and striking indiscriminately at friends and foes. This berserker rage seems to have been much applauded, and gained the possessed viking a noble distinction in the eyes of his companions. If a sea-king heard of a fair damsel anywhere along the neighboring coast, he simply took ship in that direction, fought for her, and carried her away in triumph with as many of her goods as he was lucky enough to seize beside. Their very gods were gods of war and destruction, though beside Thor, the thunderer, they worshipped Balder, the fair-faced, the god of gentle speech and purity, with Freyr, who rules over sunshine and growing things. Their hell was a place of cold and darkness, and their heaven was to be a place where fighting went on from sunrise until the time came to ride back to Valhalla and feast together in the great hall. Those who died of old age or sickness, instead of in battle, must go to hell. Odin, who was chief of all the gods, made man, and gave him a soul which should never perish, and Frigga, his wife, knew the fate of all men, but never told her secrets.

The Northmen spread themselves at length over a great extent of country. We can only wonder why, after their energy and valor led them to found a thriving colony in Iceland and in Russia, to even venture among the icebergs and perilous dismal coasts of Greenland, and from thence downward to the pleasanter shores of New England, why they did not seize these possessions and keep the credit of discovering and settling America. What a change that would have made in the world's history! Historians have been much perplexed at the fact of Leif Ericson's lack of interest in the fertile Vinland, New England now, which he visited in 986 and praised eloquently when he left it to its fate. Vinland waited hundreds of years after that for the hardy Icelander's kindred to come from old England to build their houses and spend the rest of their lives upon its good corn-land and among the shadows of its great pine-trees. There was room enough for all Greenland, and to spare, but we cannot help suspecting that the Northmen were not very good farmers, that they loved fighting too well, and would rather go a thousand miles across a stormy sea to plunder another man of his crops than to patiently raise their own corn and wool and make an honest living at home. So, instead of understanding what a good fortune it would be for their descendants, if they seized and held the great western continent that stretched westward from Vinland until it met another sea, they kept on with their eastward raids, and the valleys of the Elbe and the Rhine, of the Seine and Loire, made a famous hunting-ground for the dragon ships to seek. The rich seaports and trading towns, the strongly walled Roman cities, the venerated abbeys and cathedrals with their store of wealth and provisions, were all equally exposed to the fury of such attacks, and were soon stunned and desolated. What a horror must have fallen upon a defenceless harbor-side when a fleet of the Northmen's ships was seen sweeping in from sea at day-break! What a smoke of burning houses and shrieking of frightened people all day long; and as the twilight fell and the few survivors of the assault dared to creep out from their hiding-places to see the ruins of their homes, and the ships putting out to sea again loaded deep with their possessions! -- we can hardly picture it to ourselves in these quiet days.

Viking, p. 17

The people who lived in France were of another sort, but they often knew how to defend themselves as well as the Northmen knew how to attack. There are few early French records for us to read, for the literature of that early day was almost wholly destroyed in the religious houses and public buildings of France. Here and there a few pages of a poem or of a biography or chronicle have been kept, but from this very fact we can understand the miserable condition of the country.

In the year 810 the Danish Norsemen, under their king, Gottfried, overran Friesland, but the Emperor Charlemagne was too powerful for them and drove them back. After his death they were ready to try again, and because his huge kingdom had been divided under many rulers, who were all fighting among themselves, the Danes were more lucky, and after robbing Hamburg several times they ravaged the coasts and finally settled themselves as comfortably as possible at the mouth of the Loire in France. Soon they were not satisfied with going to and fro along the seaboard, and took their smaller craft and voyaged inland, swarming up the French rivers by hundreds, devastating the country everywhere they went.

In 845 they went up the Seine to Paris, and plundered Paris too, more than once; and forty years later, forty thousand of them, led by a man named Siegfried, went up from Rouen with seven hundred vessels and besieged the poor capital for ten months, until they were bought off at the enormous price of the whole province of Burgundy. See what power that was to put into the hands of the sea-kings' crews! But no price was too dear, the people of Paris must have thought, to get rid of such an army in the heart of Gaul. They could make whatever terms they pleased by this time, and there is a tradition that a few years afterward some bands of Danish rovers, who perhaps had gone to take a look at Burgundy, pushed on farther and settled themselves in Switzerland.

From the settlements they had made in the province of Aquitania, they had long before this gone on to Spain, because the rich Spanish cities were too tempting to be resisted. They had forced their way all along the shore of the sea, and in at the gate of the Mediterranean; they wasted and made havoc as they went, in Spain, Africa, and the Balearic islands, and pushed their way up the Rhone to Valence. We can trace them in Italy, where they burned the cities of Pisa and Lucca, and even in Greece, where at last the pirate ships were turned about, and set their sails for home. Think of those clumsy little ships out on such a journey with their single masts and long oars! Think of the stories that must have been told from town to town after these strange, wild Northern foes had come and gone! They were like hawks that came swooping down out of the sky, and though Spain and Rome and Greece were well enough acquainted with wars, they must have felt when the Northmen came, as we should feel if some wild beast from the heart of the forest came biting and tearing its way through a city street at noontime.

The whole second half of the ninth century is taken up with the histories of these invasions. We must follow for a while the progress of events in Gaul, or France as we call it now, though it was made up then of a number of smaller kingdoms. The result of the great siege of Paris was only a settling of affairs with the Northmen for the time being; one part of the country was delivered from them at the expense of another. They could be bought off and bribed for a time, but there was never to be any such thing as their going back to their own country and letting France alone for good and all. But as they gained at length whole tracts of country, instead of the little wealth of a few men to take away in their ships as at first, they began to settle down in their new lands and to become conquerors and colonists instead of mere plunderers. Instead of continually ravaging and attacking the kingdoms, they slowly became the owners and occupiers of the conquered territory; they pushed their way from point to point. At first, as you have seen already, they trusted to their ships, and always left their wives and children at home in the North countries, but as time went on, they brought their families with them and made new homes, for which they would have to fight many a battle yet. It would be no wonder if the women had become possessed by a love for adventure too, and had insisted upon seeing the lands from which the rich booty was brought to them, and that they had been saying for a long time: "Show us the places where the grapes grow and the fruit-trees bloom, where men build great houses and live in them splendidly. We are tired of seeing only the long larchen beams of their high roofs, and the purple and red and gold cloths, and the red wine and yellow wheat that you bring away. Why should we not go to live in that country, instead of your breaking it to pieces, and going there so many of you, every year, only to be slain as its enemies? We are tired of our sterile Norway and our great Danish deserts of sand, of our cold winds and wet weather, and our long winters that pass by so slowly while the fleets are gone. We would rather see Seville and Paris themselves, than only their gold and merchandise and the rafters of their churches that you bring home for ship timber." One of the old ballads of love and valor lingers yet that the women used to sing: "Myklagard and the land of Spain lie wide away o'er the lee." There was room enough in those far countries where the ships went -- why then do they stay at home in Friesland and Norway and Denmark, crowded and hungry kingdoms that they were, of the wandering sea-kings?

As the years went on, the Northern lands themselves became more peaceful, and the voyages of the pirates came to an end. Though the Northmen still waged wars enough, they were Danes or Norwegians against England and France, one realm against another, instead of every man plundering for himself.

The kingdoms of France had been divided and weakened, and, while we find a great many fine examples of resistance, and some great victories over the Northmen, they were not pushed out and checked altogether. Instead, they gradually changed into Frenchmen themselves, different from other Frenchmen only in being more spirited, vigorous, and alert. They inspired every new growth of the religion, language, or manners, with their own splendid vitality. They were like plants that have grown in dry, thin soil, transplanted to a richer spot of ground, and sending out fresh shoots in the doubled moisture and sunshine. And presently we shall find the Northman becoming the Norman of history. As the Northman, almost the first thing we admire about him is his character, his glorious energy; as the Norman, we see that energy turned into better channels, and bringing a new element into the progress of civilization.

The Northmen had come in great numbers to settle in Gaul, but they were scattered about, and so it was easier to count themselves into the population, instead of keeping themselves separate. Some of these settlements were a good way inland, and everywhere they mixed their language with the French for a time, but finally dropped it almost altogether. In a very few years, comparatively speaking, they were not Danes or Norwegians at all; they had forgotten their old customs, and even their pagan gods of the Northern countries from which their ancestors had come. At last we come to a time when we begin to distinguish some of the chieftains and other brave men from the crowd of their companions. The old chronicles of Scandinavia and Denmark and Iceland cannot be relied upon like the histories of Greece or Rome. The student who tries to discover when this man was born, and that man died, from a saga, is apt to be disappointed. The more he studies these histories of the sea-kings and their countries, the more distinct picture he gets of a great crowd of men taking their little ships every year and leaving the rocky, barren coasts of their own country to go southward. As we have seen, France and England and Flanders and Spain were all richer and more fruitful, and they would go ashore, now at this harbor, now that, to steal all they could, even the very land they trod upon. Now and then we hear the name of same great man, a stronger and more daring sailor and fighter than the rest. There is a dismal story of a year of famine in France, when the north wind blew all through the weeks of a leafless spring, the roots of the vines were frozen, and the fruit blossoms chilled to the heart. The wild creatures of the forest, crazed with hunger, ventured into the farms and villages, and the monks fasted more than they thought best, and prayed the more heartily for succor in their poverty. But down from the North came Ragnar Lodbrok, the great Danish captain, with his stout-built vessels, "ten times twelve dragons of the sea," and he and his men, in their shaggy fur garments, went crashing through the ice of the French rivers, to make an easy prey of the hungry Frenchmen -- to conquer everywhere they went. And for one Ragnar Lodbrok, read fifty or a hundred; for, though there are many stories told about him, just as we think that we can picture him and his black-sailed ships in our minds, we are told that this is only a legend, and that there never was any Ragnar Lodbrok at all who was taken by his enemies and thrown into a horrible dungeon filled with vipers, to sing a gallant saga about his life and misdeeds. But if there were no hero of this name, we put together little by little from one hint and another legend a very good idea of those quarrelsome times, when to be great it was necessary to be a pirate, and to kill as many men and steal as much of their possession as one possibly could. These Northmen set as bad an example as any traveller since the world began. More than ninety times we can hear of them in France and Spain and the north of Germany, and always burning and ruining, not only the walled cities, but all the territory round about. Shipload after shipload left their bones on foreign soil; again and again companies of them were pushed out of France and England and defeated, but from generation to generation the quarrels went on, and we begin to wonder why the sea-coasts were not altogether deserted, until we remember that the spirit of those days was war-like, and that, while the people were plundered one year, they succeeded in proving themselves masters the next, and so life was filled with hope of military glory, and the tide of conquest swept now north, and now south.

From the fjords of Norway a splendid, hardy race of young men were pushing their boats to sea every year. Remember that their own country was a very hard one to live in with its long, dark winters, its rainy, short summers when the crops would not ripen, its rocky, mountainous surface, and its natural poverty. Even now if it were not for the fishing the Norwegian peasant people would find great trouble in gaining food enough. In early days, when the tilling of the ground was less understood, it must have been hard work tempting those yellow-haired, eager young adventurers to stay at home, when they could live on the sea in their rude, stanch little ships, as well as on land; when they were told great stories of the sunshiny, fruitful countries that lay to the south, where plenty of food and bright clothes and gold and silver might be bought in the market of war for the blows of their axes and the strength and courage of their right arms. No wonder that it seemed a waste of time to stay at home in Norway!

And as for the old men who had been to the fights and followed the sea-kings and brought home treasures, we are sure that they were always talking over their valiant deeds and successes, and urging their sons and grandsons to go to the South. The women wished their husbands and brothers to be as brave as the rest, while they cared a great deal for the rich booty which was brought back from such expeditions. What a hard thing it must have seemed to the boys who were sick or lame or deformed, but who had all the desire for glory that belonged to any of the vikings, and yet must stay at home with the women!

When we think of all this, of the barren country, and the crowd of people who lived in it, of the natural relish for a life of adventure, and the hope of splendid riches and fame, what wonder that in all these hundreds of years the Northmen followed their barbarous trade and went a-ravaging, and finally took great pieces of the Southern countries for their own and held them fast.

As we go on with this story of the

Normans, you will watch these followers of the sea-kings keeping

always some trace of their old habits and customs. Indeed you

may know them yet. The Northmen were vikings, always restless

and on the move, stealing and fighting their way as best they

might, daring, adventurous. The Norman of the twelfth century

was a crusader. A madness to go crusading against the Saracen

possessed him, not alone for religion's sake or for the holy

city of Jerusalem, and so in all the ages since one excuse after

another has set the same wild blood leaping and made the

Northern blue eyes shine. Look where you may, you find

Englishmen of the same stamp -- Sir Walter Raleigh

and Lord Nelson, Stanley and Dr. Livingstone and General Gordon,

show the old sea-kings' courage and recklessness. Snorro Sturleson's best saga has been

followed by Drayton's "Battle of Agincourt" and Tennyson's

"Charge of the Light Brigade" and "Ballad of Sir Richard

Grenville." I venture to say that there is not an

English-speaking boy or girl who can hear that sea-king's ballad

this very day in peaceful England or America without a great

thrill of sympathy.

"At Flores in the Azores Sir Richard

Grenville lay,

And a pinnace, like a fluttered bird,

came flying from far away:

'Spanish ships of war at sea! We have

sighted fifty-three.'" --

Go and read that; the whole of the spirited story; but there is one thing I ask you to remember first in all this long story of the Normans: that however much it seems to you a long chapter of bloody wars and miseries and treacheries that get to be almost tiresome in their folly and brutality; however little profit it may seem sometimes to read about the Norman wars, yet everywhere you will catch a gleam of the glorious courage and steadfastness that have won not only the petty principalities and dukedoms of those early days, but the great English and American discoveries and inventions and noble advancement of all the centuries since.

On the island of Vigr, in the Folden-fiord, the peasants still show some rude hollows in the shore where the ships of Rolf-Ganger were drawn up in winter, and whence he launched them to sail away to the Hebrides and France -- the beginning of as great changes as one man's voyage ever wrought.

Jewett's Note

the skalds (poets) have produced

innumerable sagas: Depping: "Maritimes

Voyages des Normands."

O’er the glad waters of the dark blue sea,

Our thoughts as boundless, and our souls as free,

Far as the breeze can bear, the billows foam,

Survey our empire, and behold our home!

These are our realms, no limit to their sway,—

Our flag the sceptre all who meet obey.

[ Back ]

Western Islands: The gulf stream flows along the western coasts of Ireland and Great Britain, including the Hebrides (Western Islands) and the Orkney's (Faroë), islands off the western and northern coast of Scotland.

[ Back]

[ Back ]

hankering after pomp and pageantry: The old writer apparently is Rudolph Keyser, The Private Life of the Old Northmen (London 1868). In his introduction, he says, "With a hankering after pomp and pageantry—from which the old Northmen, even from the very earliest ages, had not been entirely free—there was now united a desire to imitate the more comfortable manner of life adopted by southern nations; and thus the domestic habits of the people either underwent a sudden and radical change, or gradually adapted themselves to the pattern from which they were copied."

[See Jewett's Sources for a link.]

[ Back ]

woman named Geirrid: This story is in Keyser – p. 129. He spells her home area as Haalogaland. Wikipedia says: "Hålogaland was the northernmost of the Norwegian provinces in the medieval Norse sagas."

[ Back ]

"Long Serpent": According to Wikipedia, The "Long Serpent" was a ship of "Olaf Tryggvason (960s – 1000) ... King of Norway from 995 to 1000.

[ Back ]

Harold Haarfager's time: Wikipedia says: "Harald Halfdansson (c. 850 – c. 932), better known as Harald Hårfagre (English: Harald Fairhair), was remembered by medieval historians as the first King of Norway." He was said to be the great grandfather of Olaf Tryggvason of the "Long Serpent."

[ Back ]

Friesland: According to Wikipedia, Friesland "... is a province in the north of the Netherlands and part of the ancient, larger region of Frisia."

[ Back ]

Balearic islands: According to Wikipedia, "The Balearic Islands … are an archipelago of Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula."

[ Back ]

“Myklagard and the land of Spain ....": Wikipedia says that Miklagard is from Old Norse for Constantinople. Francis Palgrave quotes this song, but with differences, in The History of Normandy and of England, Volume 1, p. 442. He says, "Well might the Norwegian damsels sing in their ballads of heroism and love…."

[See Jewett's Sources for a link.]

[ Back ]

Ragnar Lodbrok: According to Wikipedia, "Ragnar Lodbrok … was a legendary Norse ruler and hero from the Viking Age described in Old Norse poetry and several sagas.… While his sons are historical figures, it is uncertain whether Ragnar himself existed. Many of the tales about him appear to originate with the deeds of several historical Viking heroes and rulers.

According to legend, Ragnar was thrice married: to the shieldmaiden Lagertha, to the noblewoman Thora Town-Hart, and to the warrior queen Aslaug. Said to have been a relative of the Danish king Gudfred or a son of king Sigurd Hring, he became king himself and distinguished himself by many raids and conquests until he was eventually seized by his foe, King Ælla of Northumbria, and killed by being thrown into a pit of snakes. His sons bloodily avenged him by invading England with the Great Heathen Army."

[ Back ]

Snorro Sturleson's best saga has been followed by Drayton's "Battle of Agincourt" and Tennyson's "Charge of the Light Brigade" and "Ballad of Sir Richard Grenville": Wikipedia says "Snorri Sturluson (1179 – 23 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician…. He was the author of the Prose Edda or Younger Edda, which consists of Gylfaginning ("the fooling of Gylfi"), a narrative of Norse mythology, the Skáldskaparmál, a book of poetic language, and the Háttatal, a list of verse forms. He was also the author of the Heimskringla, a history of the Norwegian kings that begins with legendary material in Ynglinga saga and moves through to early medieval Scandinavian history. For stylistic and methodological reasons, Snorri is often taken to be the author of Egil's saga."

Michael Drayton (1563 – 23 December 1631) was an Elizabethan poet, author of "The Battle of Agincourt."

Wikipedia says that Alfred Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) "was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular British poets," well-remembered as the author of "The Charge of the Light Brigade." Tennyson's "The Ballad of Richard Grenville," is known as "The Revenge: A Ballad of the Fleet," which opens with the lines Jewett quotes.

[ Back ]

"... innumerable sagas": The full citation of Jewett's source is: Depping, Georges-Bernard (1784-1853). Histoire des expéditions maritimes des Normands et de leur etablissement en France au dixième siècle (“History of the sea voyages of the Normans and their settlement in France during the 10th century,”) 1826.

I have not found any English translation that would have been available to her, suggesting that she read this in French and made her own translation. The original French text is available at: https://archive.org/stream/histoiredesexp00deppuoft#page/n7/mode/2up.

My French-speaking helper, Jeannine Hammond, has not succeeded in finding the passage Jewett quotes. The above is a second edition (1843), extensively revised, according to the title page. It is possible, therefore, that Jewett had access to an 1826 edition and that her quotation is from that text. But it is equally possible that she constructed a summary and presented it as a quotation. Ms. Hammond points out that Jewett's rendering of Depping's title in her note is ungrammatical French, suggesting that perhaps she had access to an unknown English translation. However, it also is the case that Jewett often was imprecise about her English language sources, including rendering of titles, in ways bound to irritate professional scholars. See Jewett's Sources.

The following passage from Depping's notes contains several of the ideas Jewett includes in her "quotation." We have given it in French, followed by Ms. Hammond's translation.

Longtemps après l'époque des expéditions maritimes des Normands, on mit par écrit les sagas ou traditions sur les événements ou les personnes du Nord, qui se transmettaient d'une génération à l'autre, et dont la prose était mêlée des vers d'anciens scaldes ou poètes. C'est dans l'île d'Islande que les sagas ont été rédigées dans un espace de temps qui embrasse les xiie, xiiie, et xive, siècles.

Ceux qui les ont écrites relèvent la simplicité de leur style par des citations poétiques; ce sont donc les poètes qui ont commencé à conserver les faits historiques. A l'instar de ceux d'autres nations, les poètes du Nord chantaient les exploits des grandes familles qui les protégeaient, et les faits propres à intéresser et à toucher le peuple; il était très naturel que lorsque les chants se turent, et lorsque l'écriture devint plus commune, on mît par écrit les sagas ou traditions qui avaient eu le plus de vogue dans le temps du paganisme, et qu'on les appuyât du témoignage des scaldes qui les avaient chantées. Plus les sagas portent l'empreinte poétique, plus on peut les regarder comme anciennes.

Grâce à ces recueils, rédigés, à ce qu'il paraît, avec assez de bonne foi, nous avons un tableau animé des âges antiques, où le droit du plus fort était dans toute sa vigueur, et où les mœurs nationales avaient encore leur rudesse primitive. Toutefois, elles ne sont pas encore tout-à-fait de l'hisloire; les sagas les plus anciennes, du moins, ne sortent jamais du cercle étroit des épisodes, et l'on dirait que le monde s'est borné, pour leurs auteurs, aux lieux où leurs héros ont séjourné. Les personnes sont tout pour eux; temps et nations ne leur paraissent que des accessoires insignifiants. Aussi, ne faut-il y chercher ni dates, ni faits généraux, ni événements contemporains. « Ce n'était pas, dit P. E. Millier, l'importance politique des événements qui déterminaient les poètes à les chanter; ils s'attachaient uniquement à ce qu'il y avait de touchant pour le cœur des auditeurs; ainsi ils ne s'occupaient point de la prospérité et de la décadence des empires, ni des invasions et des émigrations des peuples, parce que ces faits intéressaient moins que le combat à outrance entre deux héros; il fallait, d'ailleurs, que l'événement qu'ils avaient à chanter se prêtât à des formes poétiques. (472-3).

Long after the period of the maritime expeditions of the Normans, the sagas or traditions about events or people of the North were written down and passed from one generation to another, and that prose was interspersed with verses composed by ancient skalds or poets. These sagas were written down on the island of Iceland during a period that spans the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries.

Those who wrote them down elevate the simplicity of their style with poetic quotations, so we know that it was poets who began the conservation of historical facts. As did those of other nations, the poets of the North sang of the exploits of the great families that protected them, and of the deeds which would interest and touch the people. So it was very natural that when the singing ceased, and when writing became more common, the sagas and traditions that had been most popular in pagan times were written down, and they were strengthened by association with the testimony of the ancient skalds who had sung them. The more poetic overtones these sagas have, the more they can be thought of as being of ancient origin.

Thanks to these collections, written down, it would seem, with an effort toward accuracy, we have a vivid picture of ancient ages, where the law of the strongest was in full force, and where the national customs still had their primitive harshness. However, they are still not yet a form of history. The oldest sagas, at least, never leave the narrow circle of episodes, and one might say that, for their authors, the world is limited to the places where their heroes have lived. They are interested only in the people; time and nations appear to them as only insignificant accessories. As a result, it is worthless to look for dates, general facts, or contemporary events. “It was not,” says P.E. Miller, “the political importance of the events which inspired poets to sing about them; they were interested only in what could touch the heart of the listeners; so they were uninterested in the prosperity or the decadence of empires, or invasions or the emigrations of peoples, because these facts were less compelling than the fight to the death between two heroes; and it was important, besides, that the event they would sing about lend itself to poetic formulas."

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller

Assistance from: Allison Anderson and Gabe Heller.