The Normans

by Sarah Orne Jewett

Chapter IV.

| Return to The Normans |

The Normans

by Sarah Orne Jewett

Chapter IV.

RICHARD THE FEARLESS "By many a warlike feat

Lopped the French lilies." -- Drayton.

Around the city of Bayeux, were the headquarters of the Northmen, and both Rolf's followers and the later colonists had kept that part of the duchy almost free from French influence. There Longsword's little son Richard (whose mother was Espriota, the duke's first wife, whom he had married in Danish fashion), was sent to learn the Northmen's language, and there he lived yet with his teachers and Count Bernard, when the news came of the murder of his father by Arnulf of Flanders, with whom William had gone to confer in good faith.

We can imagine for ourselves the looks of the little lad and his surroundings. He was fond even then of the chase, and it might be on some evening when he had come in with the huntsmen that he found a breathless messenger who had brought the news of Longsword's death. We can imagine the low roofed, stone-arched room with its thick pillars, and deep stone casings to the windows, where the wind came in and made the torches flare. At each end of the room would be a great fire, and the servants busy before one of them with the supper, and there on the flagstones, in a dark heap, is the stag, and perhaps some smaller game that the hunters have thrown down. There are no chimneys, and the fires leap up against the walls, and the smoke curls along the ceiling and finds its way out as best it can.

One end of the room is a step or two higher than the other, and here there is a long table spread with drinking-horns and bowls, and perhaps some beautiful silver cups, with figures of grapevines and fauns and satyrs carved on them, which the Norse pirates brought home long ago from Italy. The floor has been covered with rushes which the girls of the household scatter, and some of these girls wear old Norse ornaments of wrought silver, with bits of coral, that must have come from Italy too. The great stag-hounds are stretched out asleep after their day's work, and the little Richard is tired too, and has thrown himself into a tall carved chair by the fire.

Suddenly there comes the sound of a horn, and everybody starts and listens. Was the household to be attacked and besieged? for friends were less likely visitors than enemies in those rough times.

The dogs bark and cannot be quieted, and again the horn sounds outside the gate, and somebody has gone to answer it, and those who listen hear the great hinges creak presently as the gate is opened and the sound of horses' feet in the courtyard. The dogs have found that there is no danger and creep away lazily to go to sleep again, but when the men of the household come back to the great hall their faces are sadly changed. Something has happened.

Among them are two guests, two old counts whom everybody knows, and they walk gravely with bent heads toward the boy Richard, who stands by the smaller fire, in the place of honor, near his father's chair. Has his father come back sooner than he expected? The boy's heart must beat fast with hope for one minute, then he is frightened by the silence in the great hall. Nobody is singing or talking; there is a dreadful stillness; the very dogs are quiet and watching from their beds on the new-strewn rushes. The fires snap and crackle and throw long shadows about the room.

What are the two counts going to do -- Bernard Harcourt and Rainulf Ferrières? They are kneeling before the little boy, who is ready to run away, he does not know why. Count Bernard has knelt before him, and says this, as he holds Richard's small hand: "Richard, Duke of Normandy, I am your liegeman and true vassal"; and then the other count does and says the same, while Bernard stands by and covers his face with his hands and weeps.

Richard stands, wondering, as all the rest of the noblemen promise him their service and the loyalty of their castles and lands, and suddenly the truth comes to him. His dear father is dead, and he must be the duke now; he, a little stupid boy, must take the place of the handsome, smiling man with his shining sword and black horse and purple robe and the feather with its shining clasp in the high ducal cap that is as splendid as any crown. Richard must take the old counts for his playfellows, and learn to rule his province of Normandy; and what a long, sad, frightened night that must have been to the fatherless boy who must win for himself the good name of Richard the Fearless!

Next day they rode to Rouen, and there, when the nobles had come, the dead duke was buried with great ceremony, and all the people mourned for him and were ready to swear vengeance on his treacherous murderer. After the service was over Richard was led back from the cathedral to his palace, and his heavy black robes were taken off and a scarlet tunic put on; his long brown hair was curled, and he was made as fine as a little duke could be, though his eyes were red with crying, and he hated all the pomp and splendor that only made him the surer that his father was gone.

They brought him down to the great hall of the palace, and there he found all the barons who had come to his father's burial, and the boy was told to pull off his cap to them and bow low in answer to their salutations. Then he slowly crossed the hall, and all the barons walked after him in a grand procession according to rank -- first the Duke of Brittany and last the poorest of the knights, all going to the Church of Notre Dame, the great cathedral of Rouen, where the solemn funeral chants had been sung so short a time before.

There were all the priests and the Norman bishops, and the choir sang as Richard walked to his place near the altar where he had seen his father sit so many times. All the long services of the mass were performed, and then the boy-duke gave his promise, in the name of God and the people of Normandy, that he would be a good and true ruler, guard them from their foes, maintain truth, punish sin, and protect the Church. Two of the bishops put on him the great mantel of the Norman dukes, crimson velvet and trimmed with ermine; but it was so long that it lay in great folds on the ground. Then the archbishop crowned the little lad with a crown so wide and heavy that one of the barons had to hold it in its place. Last of all, they gave him his father's sword, taller than he, but he reached for the hilt and held it fast as he was carried back to his throne, though Count Bernard offered to carry it. Then all the noblemen did homage, from Duke Alan of Brittany down, and Richard swore in God's name to be the good lord of every one and to protect him from his foes. Perhaps some of the elder men who had followed Rolf the Ganger felt very tenderly toward this grandchild of their brave old leader, and the friends of kind-hearted Longsword meant to be loyal and very fatherly to his defenceless boy, upon whom so much honor, and anxiety too, had early fallen.

See what a change there was in Normandy since Rolf came, and what a growth in wealth and orderliness the dukedom had made. All the feudal or clannish spirit had had time to grow, and Normandy ranked as the first of the French duchies. Still it would be some time yet before the Danes and Norwegians of the north could cease to think of the Normans as their brothers and cousins, and begin to call them Frenchmen or Welskes, or any of the other names they called the people in France or Britain. It was sure to be a hard dukedom enough for the boy-duke to rule, and all his youth was spent in stormy, dangerous times.

His father had stood godfather -- a very close tie -- to the heir of the new king of France, who was called Louis, and he was also at peace with Count Hugh of Paris. Soon after Longsword's death King Louis appeared in Rouen at the head of a body of troops, and demanded that he should be considered the guardian and keeper of young Richard during his minority. He surprised the counts who were in Rouen, and who were just then nearly defenceless. It would never do for them to resist Louis and his followers; they had no troops at hand; and they believed that the safest thing was to let Richard go, for a time at any rate. It was true that he was the king's vassal, and Normandy had always done homage to the kings of France. And with a trusty baron for protection the boy was sent away out of pleasant Normandy to the royal castle of Laon. The Rouen people were not very gracious to King Louis, and that made him angry. Indeed, the French king's dominion was none too large, and everybody knew that he would be glad to possess himself of the dukedom, or of part of it, and that he was not unfriendly to Arnulf, who had betrayed William Longsword. So the barons who were gathered at Rouen, and all the Rouen people, must have felt very anxious and very troubled about Richard's safety when the French horsemen galloped away with him. From time to time news came that the boy was not being treated very well. At any rate he was not having the attention and care that belonged to a duke of Normandy. The dukedom was tempestuous enough at any time, with its Northman party, and its French party, and their jealousies and rivalries. But they were all loyal to the boy-duke who belonged to both, and who could speak the pirate's language as well as that of the French court. If his life were brought to an untimely end what a falling apart there would be among those who were not unwilling now to be his subjects. No wonder that the old barons were so eager to get Richard home again, and so distrustful of the polite talk and professions of affection and interest on King Louis's part. Louis had two little sons of his own, and it would be very natural if he sometimes remembered that, if Richard were dead, one of his own boys might be Duke of Normandy instead -- that is, if old Count Hugh of Paris did not stand in the way.

So away went Richard from his pleasant country of Normandy, with its apple and cherry orchards and its comfortable farms, from his Danes and his Normans, and the perplexed and jealous barons. A young nobleman, named Osmond de Centeville, was his guardian, and promised to take the best of care of his young charge, but when they reached the grim castle of Laon they found that King Louis' promises were not likely to be kept. Gerberga, the French queen, was a brave woman, but eager to forward the fortunes of her own household, and nobody took much notice of the boy who was of so much consequence at home in his own castle of Rouen. We cannot help wondering why Richard's life did not come to a sudden end like his father's, but perhaps Osmond's good care and vigilance gave no chance for treachery to do its work.

After a while the boy-duke began to look very pale and ill, poor little fellow, and Osmond watched him tenderly, and soon the rest of the people in the castle had great hopes that he was going to die. The tradition says that he was not sick at all in reality, but made himself appear so by refusing to eat or sleep. At any rate he grew so pale and feeble that one night everybody was so sure that he could not live that they fell to rejoicing and had a great banquet. There was no need to stand guard any longer over the little chief of the pirates, and nobody takes much notice of Osmond even as he goes to and from the tower room with a long face.

Late in the evening he speaks of his war-horse which he has forgotten to feed and litter down, and goes to his stable in the courtyard with a huge bundle of straw. The castle servants see him, but let him pass as usual, and the banquet goes on, and the lights burn dim, and the night wanes before anybody finds out that there was a thin little lad, keeping very still, in the straw that Osmond carried, and that the two companions were riding for hours in the starlight toward the Norman borders. Hurrah! we can almost hear the black horse's feet clatter and ring along the roads, and take a long breath of relief when we know that the fugitives get safe to Crecy castle within the Norman lines next morning.

King Louis was very angry and sent a message that Richard must come back, but the barons refused, and before long there was a great battle. There could really be no such thing as peace between the Normans and the kingdom of France, and Louis had grown more and more anxious to rid the country of the hated pirates. Hugh the Great and he were enemies at heart and stood in each other's way, but Louis made believe that he was friendly, and granted his formidable rival some new territory, and displayed his royal condescension in various ways. Each of these rulers was more than willing to increase his domain by appropriating Normandy, and when we remember the two parties in Normandy itself we cannot help thinking that Richard's path was going to be a very rough one to follow. His father's enemy, Arnulf of Flanders, was the enemy of Normandy still, and always in secret or open league with Louis. The province of Brittany was hard to control, and while William Longsword had favored the French party in his dominions he had put Richard under the care of the Northmen. Yet this had not been done in a way to give complete satisfaction, for the elder Danes clung to their old religion and cared nothing for the solemn rites of the Church, by means of which Richard had been invested with the dukedom. They were half insulted by such silly pageantry, yet it was not to the leaders of the old pirate element in the dukedom, but to the Christianized Danes, whose head-quarters were at Rouen, that the guardianship of the heir of Normandy had been given. He did not belong to the Christians, but to the Norsemen, yet not to the old pagan vikings either. It was a curious and perhaps a very wise thing to do, but the Danes little thought when Longsword promised solemnly to put his son under their charge, that he meant the Christian Danes like Bernard and Botho. There was one thing that all the Normans agreed upon, that they would not be the vassals and lieges of the king of France. They had promised it in their haste when the king had come and taken young Richard away to Laon, but now that they had time to consider, they saw what a mistake it had been to make Louis the boy-duke's guardian. They meant to take fast hold of Richard now that he had come back, and so the barons were summoned, and when Louis appeared again in Normandy, with the spirit and gallantry of a great captain, to claim the guardianship and to establish Christianity, as well as to avenge the murder of Longsword, if you please! -- he found a huge army ready to meet him.

Nobody can understand how King Louis managed to keep such a splendid army as his in good condition through so many reverses. He had lost heavily from his lands and his revenues, and there were no laws, so far as we know, that compelled military service, but the ranks were always full, and the golden eagle of Charlemagne was borne before the king on the march, and the banner of that great emperor, his ancestor, fluttered above his pavilion when the army halted. As for the Danes (which means simply the Northern or Pirate party of Normandy), they were very unostentatious soldiers and fought on foot, going to meet the enemy with sword and shield. Some of them had different emblems on their shields now, instead of the old red and white stripes of the shields that used to be hung along the sides of the long-ships, and they carried curious weapons, even a sort of flail that did great execution.

We must pass quickly over the long account of a feigned alliance between Hugh of Paris and King Louis, their agreement to share Normandy between themselves, and then Hugh's withdrawal, and Bernard of Senlis's deep-laid plot against both the enemies of Normandy. It was just at this time that there was a great deal of enmity between Normandy and Brittany, and the Normans seem to be in a more rebellious and quarrelsome state than usual. If there was one thing that they clung to every one of them, and would not let go, it was this: that Normandy should not be divided, that it should be kept as Rolf had left it. Sooner than yield to the plots and attempted grasping and divisions of Hugh and Arnulf of Flanders, and Louis, they would send to the North for a fleet of dragon ships and conquer their country over again. They knew very well that however bland and persuasive their neighbors might become when they desired to have a truce, they always called them filthy Normans and pirates behind their backs, and were always hoping for a chance to push them off the soil of Normandy. There was no love lost between the dukedoms and the kingdom.

After some time Louis was persuaded again that Normandy desired nothing so much as to call him her feudal lord and sovereign. Bernard de Senlis assured him, for the sake of peace, that they were no longer in doubt of their unhappiness in having a child for a ruler, that they were anxious to return to the old pledge of loyalty that Rolf gave to the successor of Charlemagne. He must be the over-lord again and must come and occupy his humble city of Rouen. They were tired of being harried, their land was desolated, and they would do any thing to be released from the sorrows and penalties of war. Much to our surprise, and very likely to his own astonishment too, we find King Louis presently going to Rouen, and being received there with all manner of civility and deference. Everybody hated him just as much as ever, and distrusted him, and no doubt Louis returned the compliment, but to outward view he was beloved and honored by his tributaries, and the Norman city seemed quiet and particularly servile to its new ruler and his bragging troops. Nobody understood exactly why they had won their ends with so little trouble, and everybody was on the watch for some amazing counterplot, and dared not trust either friend or foe. As for Louis, they had shamed and tormented him too much to make him a very affectionate sovereign now. To be sure he ruled over Normandy at last, but that brought him perplexity enough. In the city the most worthless of his followers was putting on the airs of a conqueror and aggravating the Norman subjects unbearably. The Frenchmen who had followed the golden eagle of Charlemagne so long without any reward but glory and a slender subsistence, began to clamor for their right to plunder the dukedom and to possess themselves of a reward which had been too long withheld already.

Hugh, of Paris, and King Louis had made a bold venture together for the conquest of Normandy, and apparently succeeded to their heart's content. Hugh had besieged Bayeux; and the country, between the two assailants, had suffered terribly. Bernard the Dane, or Bernard de Senlis either, knew no other way to reëstablish themselves than by keeping Louis in Rouen and cheating him by a show of complete submission. The Normans must have had great faith in the Danish Bernard when they submitted to make unconditional surrender to Louis. Could it be that he had been faithless to the boy-duke's rights, and allowed him to be contemptuously disinherited?

Flail as a Military Weapon (2).

Now that the king was safely bestowed in Rouen, his new liegemen began to say very disagreeable things. Louis had made a great fool of himself at a banquet soon after he reached Rolf's tower in the Norman city. Bernard the Dane, had spread a famous feast for him and brought his own good red wine. Louis became very talkative, and announced openly that he was going to be master of the Normans at last, and would make them feel his bonds, and shame them well. But Bernard the Dane left his own seat at the table and placed himself next the king. Presently he began, in most ingenious ways, to taunt him with having left himself such a small share of the lands and wealth of the ancient province of Neustria. He showed him that Hugh of Paris had made the best of the bargain, and that he had given up a great deal more than there was any need of doing. Bernard described in glowing colors the splendid dominions he had sacrificed by letting his rival step in and take first choice. Louis had not chosen to take a seventh part of the whole dukedom, and Hugh of Paris was master of all Normandy beyond the Seine, a beautiful country watered by fine streams whose ports were fit for commerce and ready for defence. More than this; he had let ten thousand fighting men slip through his hands and become the allies of his worst enemy. And so Bernard and his colleagues plainly told Louis that he had made a great mistake. They would consent to receive him as their sovereign and guardian of the young duke, but Normandy must not be divided; to that they would never give their consent.

Louis listened, half dazed to these suggestions, and when he was well sobered he understood that he was attacked on every side. Hugh of Paris had declared that if Louis broke faith with him now he would make an end to their league, and Louis knew that he would be making a fierce enemy if he listened to the Normans; yet if he refused, they would turn against him.

On the other hand, if he permitted Hugh to keep his new territory, he was only strengthening a man who was his enemy at heart, and who sooner or later would show his antagonism. Louis's own soldiers were becoming very rebellious. They claimed over and over again that Rolf had had no real right to the Norman lands, but since he had divided them among his followers, all the more reason now that the conquerors, the French owners of Normandy, should be put into possession of what they had won back again at last. They demanded that the victors should enforce their right, and not only expressed a wish for Bernard the Dane's broad lands, but for his handsome young wife. They would not allow that the Normans had any rights at all. When a rumor of such wicked plans began to be whispered through Rouen and the villages, it raised a great excitement. There would have been an insurrection at once, if shrewd old Bernard had not again insisted upon patience and submission. His wife even rebelled, and said that she would bury herself in a convent; and Espriota, young Richard's mother, thriftily resolved to provide herself with a protector, and married Sperling, a rich miller of Vaudreuil.

Hugh of Paris was Bernard's refuge in these troubles, and now we see what the old Dane had been planning all the time. Hugh had begun to believe that there was no use in trying to hold his new possessions of Normandy beyond the Seine, and that he had better return to his old cordial alliance with the Normans and uphold Rolf the Ganger's dukedom. So the Danish party, Christians and pagans, and the Normans of the French party, and Hugh of Paris, all entered into a magnificent plot against Louis. The Normans might have been contented with expelling the intruders, and a renunciation of the rights Louis had usurped, but Hugh the Great was very anxious to capture Louis himself.

Besides Hugh of Paris and the Norman barons who upheld the cause of young Richard, there was a third very important ally in the great rebellion against King Louis of France. When Gorm a famous old king of Denmark had died some years before, the successor to his throne was Harold Blaatand or Bluetooth, a man of uncommonly fine character for those times -- a man who kept his promises and was noted for his simplicity and good faith and loyalty to his word. Whatever reason may have brought Harold to Normandy at this time, there he was, the firm friend of the citizens of the Bayeux country, and we find him with his army at Cherbourg.

All Normandy was armed and ready for a grand fight with the French, though it appears that at first there was an attempt at a peaceful conference. This went on very well at first, the opposing armies being drawn up on either side of the river Dive, when who should appear but Herluin of Montreuil, the insolent traitor who was more than suspected of having caused the murder of William Longsword. Since then he had ruled in Rouen as Louis's deputy and stirred up more hatred against himself, but now he took a prominent place in the French ranks, and neither Normans nor Danes could keep their tempers any longer. So the peaceful conference was abruptly ended, and the fight began.

Every thing went against the French: many counts were killed; the golden eagle of Charlemagne and the silk hangings and banners of the king's tent had only been brought for the good of these Normans, who captured them. As for the king himself, he was taken prisoner; some say that he was led away from the battle-field and secreted by a loyal gentleman of that neighborhood, who hid him in a secluded bowery island in the river near by, and that the poor gentleman's house and goods were burnt and his wife and children seized, before he would tell anything of the defeated monarch's hiding-place. There is another story that Harold Blaatand and Louis met in hand-to-hand combat, and the Dane led away the Frank as the prize of his own bravery. The king escaped and was again captured and imprisoned in Rouen. No bragging now of what he would do with the Normans, or who should take their lands and their wives. Poor Louis was completely beaten, but there was still a high spirit in the man and in his brave wife Gerberga, who seems to have been his equal in courage and resource. After a while Louis only regained his freedom by giving up his castle of Laon to Hugh of Paris, and the successor of Charlemagne was reduced to the pitiful poverty of being king only of Compiegne. Yet he was still king, and nobody was more ready to give him the title than Hugh of Paris himself, though the diplomatic treacheries went on as usual.

Harold had made a triumphant progress through Normandy after the great fight was over, and all the people were very grateful to him, and it is said that he reëstablished the laws of Rolf, and confirmed the authority of the boy-duke. We cannot understand very well at this distance just why Harold should have been in Normandy at all with his army to make himself so useful, but there he was, and unless one story is only a repetition of the other, he came back again, twenty years after, in the same good-natured way, and fought for the Normans again.

Poor Louis certainly had a very hard time, and for a while his pride was utterly broken; but he was still young and hoped to retrieve his unlucky fortunes. Richard, the young duke, was only thirteen years old when Normandy broke faith with France. He had not yet earned his title of the Fearless, which has gone far toward making him one of the heroes of history, and was waiting to begin his real work and influence in the dukedom. Louis had sympathy enough of a profitless sort from his German and English neighbors. England sent an embassy to demand his release, and Hugh of Paris refused most ungraciously. Later, the king of the Germans or East Franks determined to invade Hugh's territory, and would not even send a message or have any dealings with him first; and when he found that the German army was really assembling, the Count of Paris yielded. But, as we have already seen, Louis had to give up a great piece of his kingdom. As far as words went, he was king again. He had lost his authority while he was in prison, but it was renewed with proper solemnity, and Hugh was again faithful liegeman and homager of his former prisoner. The other princes of Europe, at least those who were neighbors, followed Hugh's example -- all except one, if we may believe the Norman historians. On the banks of the Epte, where Rolf had first done homage to the French king, the Norman duchy was now set free from any over-lordship, and made an independent country. The duke was still called duke, and not king, yet he was completely the monarch of Normandy, and need give no tribute nor obedience.

Before long, however, Richard, or his barons for him -- wily Bernard the Dane, and Bernard de Senlis, and the rest -- commended the lands and men of Normandy to the Count of Paris, benefactor and ally. The Norman historians do not say much about this, for they were not so proud of it as of their being made free from the rule of France. We are certain that the Norman soldiers followed Hugh in his campaigns, for long after this during the reign of Richard the Fearless there were some charters and state papers written which are still preserved, and which speak of Hugh of Paris as Richard's over-lord.

There are so few relics of that time that we must note the coinage of the first Norman money in Richard's reign. The chronicles follow the old fashion of the sagas in sounding the praises of one man -- sometimes according to him all the deeds of his ancestors besides; but, unfortunately, they refer little to general history, and tell few things about the people. We find Normandy and England coming into closer relations in this reign, and the first mention of the English kings and of affairs across the Channel, lends a new interest to our story of the Normans. Indeed, to every Englishman and American the roots and beginnings of English history are less interesting in themselves than for their hints and explanations of later chapters and events.

Before we end this account of Duke Richard's boyhood, we must take a look at one appealing fragment of it which has been passed by in the story of the wars and tumults and strife of parties. Once King Louis was offered his liberty on the condition that he would allow the Normans to take his son and heir Lothair as pledge of his return and good behavior. No doubt the French king and Queen Gerberga had a consciousness that they had not been very kind to Richard, and so feared actual retaliation. But Gerberga offered, not the heir to the throne, but her younger child Carloman, a puny, weak little boy, and he was taken as hostage instead, and soon died in Rouen. Miss Yonge has written a charming story called "The Little Duke," in which she draws a touching picture of this sad little exile. It makes Queen Gerberga appear very hard and cruel, and it seems as if she must have been to let the poor child go among his enemies. We must remember, though, that these times were very hard, and one cannot help respecting the poor queen, who was very brave after all, and fought as gallantly as any one to keep her besieged and struggling kingdom out of the hands of its assailants.

We must pass over the long list of petty wars between Louis and Hugh. Richard's reign was stormy to begin with, but for some years before his death Normandy appears to have been tolerably quiet. Louis had seen his darkest times when Normandy shook herself free from French rule, and from that hour his fortunes bettered. There was one disagreement between Otto of Germany and Louis, aided by the king of Burgundy, against the two dukes, Hugh and Richard, and before Louis died he won back again the greater part of his possessions at Laon. Duke Hugh's glories were somewhat eclipsed for a time, and he was excommunicated by the Archbishop of Rheims and took no notice of that, but by and by when the Pope of Rome himself put him under a ban, he came to terms. The Normans were his constant allies, but there is not much to learn about their own military enterprises. The enthusiastic Norman writers give a glowing account of the failure of the confederate kings to capture Rouen, but say less about their marauding tour through the duchies of Normandy and Hugh's dominions. Rouen was a powerful city by this time, and a famous history belonged to her already. There are some fragments left still of the Rouen of that day, which is very surprising when we remember how battered and beleaguered the old town was through century after century.

Every thing was apparently prospering with the king of France when he suddenly died, only thirty-three years of age, in spite of his tempestuous reign and always changing career. He must have felt like a very old man, one would think, and somehow one imagines him and Gerberga, his wife, as old people in their Castle of Laon. Lothair was the next king, and Richard, who so lately was a child too, became the elder ruler of his time. Hugh of Paris died two years later, and the old enemy of Normandy, Arnulf of Flanders, soon followed him. The king of Germany, Otto, outlived all these, but Richard lived longer than he or his son.

The duchy of France, Hugh's dominion, passed to his young son, Hugh Capet, a boy of thirteen. When this Hugh grew up he did homage to Lothair, but Richard gave his loyalty to Hugh of Paris's son. The wars went on, and before many years went over Hugh Capet extinguished the succession of Charlemagne's heirs to the throne of France, and was crowned king himself, so beginning the reign of France proper; as powerful and renowned a kingdom as Europe saw through many generations. By throwing off the rule of German princes, and achieving independence of the former French dynasty, an order of things began that was not overthrown until our own day. Little by little the French crown annexed the dominions of all its vassals, even the duchy of Normandy, but that was not to be for many years yet. I hope we have succeeded in getting at least a hint of the history of France from the time it was the Gaul of the Roman empire; and the empire of Charlemagne, and later, of the fragments of that empire, each a province or kingdom under a ruler of its own, which were reunited in one confederation under one king of France. All this time Europe is under the religious rule of Rome, and in Richard the Fearless's later years we find him the benefactor of the Church, living close by the Minster of Fécamp and buried in its shadow at last. There was a deep stone chest which was placed by Duke Richard's order near one of the minster doors, where the rain might fall upon it that dropped from the holy roof above. For many years, on Saturday evenings, the chest was filled to the brim with wheat, a luxury in those days, and the poor came and filled their measures and held out their hands afterward for five shining pennies, while the lame and sick people were visited in their homes by the almoner of the great church. There was much talk about this hollowed block of stone, but when Richard died in 996 at the end of his fifty-five years' reign, after a long, lingering illness, his last command was that he should be buried in the chest and lie "there where the foot should tread, and the dew and the waters of heaven should fall." Beside this church of the Holy Trinity at Fécamp he built the abbey of St. Wandville, the Rouen cathedral, and the great church of the Benedictines at St. Ouen. New structures have risen upon the old foundations, but Richard's name is still connected with the places of worship that he cared for.

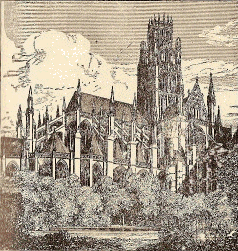

Abbey Church of St. Ouen (Rouen)

"Richard Sans-peur has long been our favorite hero," says Sir Francis Palgrave, who has written perhaps the fullest account of the Third Duke; "we have admired the fine boy, nursed on his father's knee whilst the three old Danish warriors knelt and rendered their fealty. During Richard's youth, adolescence, and age our interest in his varied, active, energetic character has never flagged, and we go with him in court and camp till the day of his death."

Notes for Chapter 4

"... Lopped the French lilies.” -- DRAYTON: These lines appear at the end of stanza six of Michael Drayton's (1563–1631) "The Ballad of Agincourt."

[ Back ]

… I am your liegeman: This description of bringing the news of William Longsword's death closely follows the narrative in Charlotte Mary Yonge's The Little Duke (see Jewett's Sources). Count Harcourt's words apparently are quoted from Yonge. While much of the substance of the narrative of Richard the Fearless's youth is presented in Palgrave's The History of Normandy and England, volume 2, Jewett clearly draws upon Yonge for much of the imaginative detail she provides.

[ Back ]

… boy duke began to look very pale: Jewett's account of the escape of Richard the Fearless from Laon depends in part upon the detailed narrative of Palgrave, The History of Normandy and England, volume 2, pp. 410-414.

[ Back ]

Miss Yonge ... “The Little Duke”: Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823-1901), The Little Duke: Richard the Fearless (1864)

Yonge's portrait of Gerberga (Gerberge) is indeed quite negative; she threatens at one point to put out Duke Richard's eyes (Chapter 8).

Jewett's caution about Yonge's portrayal of Gerberga could be based upon Palgrave's portrait of her as a canny negotiator for the safety of husband and son in The History of Normandy and England volume 2, pp. 484-7.

Sir Francis Palgrave (1788-1861) born Francis Cohen in London. "His works include A History of England (1831), The Rise and Progress of the English Commonwealth (1832), An Essay on the Original Authority of the King's Council (1834), Truths and Fictions of the Middle Ages: the Merchant and the Friar (1837) and The History of Normandy and England (1851-64, four volumes). The last two volumes of this work were published after his death." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Palgrave

[ Back ]

where the foot shall tread: Richard's burial request appears to be quoted from Palgrave, The History of Normandy and England, vol. 3, p. 27.

[ Back ]

our favorite hero: See Palgrave, The History of Normandy and of England, Vol. 3: Richard-Sans-Peur. Richard Le-Bon. Richard III. Robert Le-Diable. William the Conqueror (1864), p. 91.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller

Assistance from: Allison Anderson and Gabe Heller.

.

| Return to The Normans |