The Normans

by Sarah Orne Jewett

Chapter VIII.

THE YOUTH OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR.

"One equal temper of heroic hearts

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield."

-- Tennyson.

There was one man, famous in history, who more than any other Norman seemed to personify his race, to be the type of the Norman progressiveness, firmness, and daring. He was not only remarkable among his countrymen, but we are forced to call him one of the great men and great rulers of the world. Nobody has been more masterful, to use a good old Saxon word, and therefore he came to be master of a powerful, venturesome race of people and gathered wealth and widespread territory. Every thing would have slipped through his fingers before he was grown to manhood if his grasp had not been like steel and his quickness and bravery equal to every test. "He was born to be resisted," says one writer;* "to excite men's jealousy and to awaken their life-long animosity, only to rise triumphant above them all, and to show to mankind the work that one man can do -- one man of fixed principles and resolute will, who marks out a certain goal for himself, and will not be deterred, but marches steadily towards it with firm and ruthless step. He was a man to be feared and respected, but never to be loved; chosen, it would seem, by Providence . . . to upset our foregone conclusions, and while opposing and crushing popular heroes and national sympathies, to teach us that in the progress of nations there is something required beyond popularity, something beyond mere purity and beauty of character -- namely, the mind to conceive and the force of will to carry out great schemes and to reorganize the failing institutions and political life of states. Born a bastard, with no title to his dukedom but the will of his father; left a minor with few friends and many enemies, with rival competition at home and a jealous over-lord only too glad to see the power of his proud vassal humbled, he gradually fights his way, gains his dukedom, and overcomes competition at an age when most of us are still under tutors and governors; extends his dominions far beyond the limits transmitted to him by his forefathers, and then leaves his native soil to seek other conquests, to win another kingdom, over which again he has no claim but the stammering will of a weak king and his own irresistible energy, and what is still more strange, securing the moral support of the world in his aggression, and winning for himself the position of an aggrieved person recovering his just and undoubted rights. Truly the Normans could have no better representative of their extraordinary power."

William was only seven years old or a little more when his father left him to go on pilgrimage. No condition could have appeared more pitiable and desperate than his -- even in his childhood we become conscious of the dislike his character inspired. Often just and true to his agreements, sometimes unexpectedly lenient, nothing in his nature made him a winner and holder of friendship, though he was a leader of men and a controller of them, and an inspirer of faithful loyalty besides the service rendered him for fear's sake. His was the rule of force indeed, but there is one thing to be particularly noted -- that in a licentious, immoral age he grew up pure and self-controlled. That he did not do some bad things must not make us call him good, for a good man is one who does do good things. But his strict fashion of life kept his head clearer and his hands stronger, and made him wide-awake when other men were stupid, and so again and again he was able to seize an advantage and possess himself of the key to success.

While his father lived, the barons paid the young heir unwilling respect, and there was a grim acquiescence in what could not be helped. Alan of Brittany was faithful to his trust, and always able to check any dissensions and plots against his ward. The old animosity between him and Robert was quite forgotten, apparently; but at last Alan was poisoned. Robert's death was the signal for a general uprising of the nobles, and William's life was in peril for a dozen years. He never did homage to the king of France, but for a long time nobody did homage to him either; the barons disdained any such allegiance, and sometimes appear to have forgotten their young duke altogether in their bitter quarrels, and murders of men of their own rank. We trace William de Talvas, still the bastard's fierce enemy, through many plots and quarrels; -- it appears as if he were determined that his curse should come true, and made it the purpose of his life. The houses of Montgomery and Beaumont were linked with him in anarchy and treachery; it was the Montgomeries' deadly mischief to which the faithful Alan fell victim. William himself escaped assassination by a chance, and several of his young followers were not so fortunate. They were all in the strong castle of Vaudreuil, a place familiar to the descendants of Longsword, since it was the home of Sperling, the rich miller, whom Espriota married. The history of the fortress had been a history of crime, but Duke Robert was ready to risk the bad name for which it was famous, and trust his boy to its shelter. There had never been a blacker deed done within those walls than when William was only twelve years old, and one of his playmates, who slept in his chamber, was stabbed as he lay asleep. No doubt the Montgomery who struck the cruel blow thought that he had killed the young duke, and went away well satisfied; but William was rescued, and carried away and hidden in a peasant's cottage, while the butchery of his friends and attendants still went on. The whole country swarmed with his enemies. The population of the Côtentin, always more Scandinavian than French, welcomed the possibility of independence, and the worst side of feudalism began to assert itself boldly. Man against man, high rank against low rank, farmer against soldier, -- the bloody quarrels increased more and more, and devastated like some horrible epidemic.

There were causes enough for trouble in the state of feudalism itself to account for most of the uproar and disorder, let alone the claim of the unwelcome young heir to the dukedom. It is very interesting to see how, in public sentiment, there was always an undertone of resentment to the feudal system, and of loyalty to the idea, at least, of hereditary monarchy. Even Hugh the Great, of France, was governed by it in his indifference to his good chances for seizing the crown years before this time; and though the great empire of Charlemagne had long since tottered to its fall and dismemberment, there was still much respect for the stability and order of an ideal monarchical government.

The French people had already endured some terrible trials, but it was not because of war and trouble alone that they hated their rulers, for these sometimes leave better things behind them; war and trouble are often the only way to peace and quietness. They feared the very nature of feudalism and its political power. It seemed to hold them fast, and make them slaves and prisoners with its tangled network and clogging weights. The feudal lords were petty sovereigns and minor despots, who had certain bonds and allegiances among themselves and with each other, but they were, at the same time, absolute masters of their own domain, and their subjects, whether few or many, were under direct control and surveillance. Under the great absolute monarchies, the very extent of the population and of the country would give a greater security and less disturbance of the middle and lower classes, for a large army could be drafted, and still there would be a certain lack of responsibility for a large percentage of the subjects. Under the feudal system there were no such chances; the lords were always at war, and kept a painfully strict account of their resources. Every field and every family must play a part in the enterprises of their master, and a continual racking and robbing went on. Even if the lord of a domain had no personal quarrel to settle, he was likely to be called upon by his upholder and ally to take part with him against another. In the government of a senate or an ecclesiastical council, the common people were governed less capriciously; their favor was often sought, even in those days, by the different factions who had ends to gain, and were willing to grant favors in return; but the feudal lords were quite independent, and could do as they pleased without asking anybody's advice or consent.

This concerns the relation of the serfs to their lords, but among the lords themselves affairs were quite different. From the intricate formalities of obligation and dependence, from the necessity for each feudal despot's vigilant watchfulness and careful preparation and self-control and quick-sighted decision, arose a most active, well-developed class of nobles. While the master of a feudal castle (or robber-strong-hold, whichever we choose to call it) was absent on his forays, or more determined wars, his wife took his place, and ruled her dependents and her household with ability. The Norman women of the higher classes were already famous far and wide through Europe, and, since we are dealing with the fortunes of Normandy, we like to picture them in their castle-halls in all their dignity and authority, and to imagine their spirited faces, and the beauty which is always a power, and which some of them had learned already to make a power for good.

No matter how much we deplore the condition of Normandy and the lower classes of society, and sympathize with the wistfulness and enforced patience of the peasantry; no matter how perplexed we are at the slowness of development in certain directions, we are attracted and delighted by other aspects. We turn our heads quickly at the sound of martial music. The very blood thrills and leaps along our veins as we watch the Norman knights ride by along the dusty Roman roads. The spears shine in the sunlight, the horses prance, the robber-castles clench their teeth and look down from the hills as if they were grim stone monsters lying in wait for prey. The apple-trees are in blossom, and the children scramble out of the horses' way; the flower of chivalry is out parading, and in clanking armor, with flaunting banners and crosses on their shields, the knights ride by to the defence of Jerusalem. Knighthood was in its early prime, and in this gay, romantic fashion, with tender songs to the ladies they loved and gallantly defended, with a prayer to the Virgin Mary, their patroness, because they reverenced the honor and purity of womanhood, they fought through many a fierce fight, with the bitter, steadfast courage of brave men whose heart is in their cause. It was an easy step from their defiance of the foes of Normandy to the defence of the Church of God. Religion itself was the suggester and promoter of chivalry, and the Normans forgot their lesser quarrels and petty grievances when the mother church held up her wrongs and sufferings to their sympathy. It was to Christianity that the mediæval times owed knighthood, and, while historians complain of the lawlessness of the age, the crimes and violence, the social confusion and vulgarity, still the poetry and austerity and real beauty of the knightly traditions shine out all the brighter. Men had got hold of some new suggestions; the best of them were examples of something better than the world had ever known. As we glance over the list of rules to which a knight was obliged to subscribe, we cannot help rejoicing at the new ideal of christian manhood.

Rolf the Ganger had been proud rather than ashamed of his brutal ferocity and selfishness. This new standard demands as good soldiery as ever; in fact, a greater daring and utter absence of fear, but it recognizes the rights of other people, and the single-heartedness and tenderness of moral strength. It is a very high ideal.

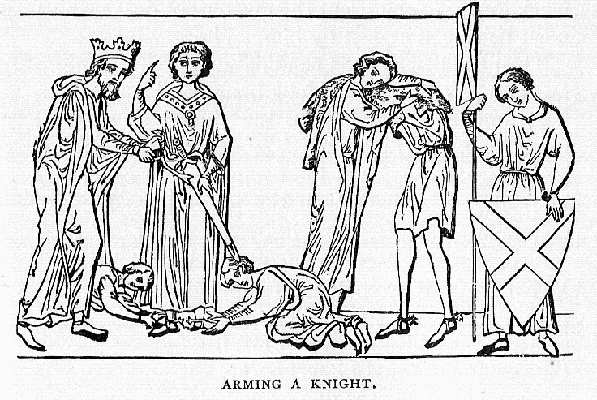

A little later than the time of William the Conqueror's youth, there were formal ceremonies at the making of a knight, and these united so surprisingly the poet's imaginary knighthood and the customs of military life and obligations of religious life, that we cannot wonder at their influence.

The young man was first stripped of his clothes and put into a bath, to wash all former contaminations from body and soul -- a typical second baptism, done by his own free will and desire. Afterward, he was clothed first in a white tunic, to symbolize his purity; next in a red robe, a sign of the blood he must be ready to shed in defending the cause of Christ; and over these garments was put a tight black gown, to represent the mystery of death which must be solved at last by him, and every man.

Then the black-robed candidate was left alone to fast and pray for twenty-four hours, and when evening came, they led him to the church to pray all night long, either by himself, or with a priest and his own knightly sponsors for companions. Next day he made confession; then the priest gave him the sacrament, and afterward he went to hear mass and a sermon about his new life and a knight's duties. When this was over, a sword was hung around his neck and he went to the altar, where the priest took off the sword, blessed it, and put it on again. Then the candidate went to kneel before the lord who was to arm him, and was questioned strictly about his reasons for becoming a knight, and was warned that he must not desire to be rich or to take his ease, or to gain honor from knighthood without doing it honor; at last the young man solemnly promised to do his duty, and his over-lord to whom he did homage granted his request to be made a knight.

After this the knights and ladies dressed him in his new garments, and the spurs came first of all the armor, then the haubert or coat of mail; next the cuirass, the armlets, and gauntlets, and, last of all, the sword. Now he was ready for the accolade; the over-lord rose and went to him and gave him three blows with the flat of the sword on his shoulder or neck, and sometimes a blow with the hand on his breast, and said: "In the name of God, of St. Michael and St. George, I make thee knight. Be valiant and fearless and loyal."

Then his horse was led in, and a helmet was put on the new knight's head, and he mounted quickly and flourished his lance and sword, and went out of the church to show himself to the people gathered outside, and there was a great cheering, and prancing of horses, and so the outward ceremony was over, and he was a dubbed knight, as the old phrase has it -- adopted knight would mean the same thing to-day; he belonged to the great Christian brotherhood of chivalry. We have seen how large a part religion played in the rites and ceremonies, but we can get even a closer look at the spirit of knighthood if we read some of the oaths that were taken by these young men, who were the guardians and scholars of whatever makes for peace, even while they chose the ways of war and did such eager, devoted work with their swords. M. Guizot, from whose "History of France" I have taken the greater part of this description, goes on to give twenty-six articles to which the knights swore, not that these made a single ritual, but were gathered from the accounts of different epochs. They are so interesting, as showing the steady growth and development of better ideas and purposes, that I copy them here. Indeed we can hardly understand the later Norman history, and the crusades particularly, unless we make the knights as clear to ourselves as we tried to make the vikings.

We must thank the clergymen of the tenth and eleventh centuries for this new thought about the duties and relationships of humanity, -- men like Abelard and St. Anselm, and the best of their contemporaries. It is most interesting to see how the church availed herself of the feudal bonds and sympathies of men, and their warlike sentiment and organization, to develop a better and more peaceful service of God. Truthfulness and justice and purity were taught by the church's influence, and licentiousness and brutality faded out as the new order of things gained strength and brightness. Later the pendulum swung backward, and the church used all the terrors of tyranny, fire, and sword, to further her ends and emphasize her authority, instead of the authority of God's truth and the peace of heavenly living. The church became a name and cover for the ambitions of men.

Whatever the pretences and mockeries and rivalries and thefts of authority may be on the part of unworthy churchmen, we hardly need to remind ourselves that in every age the true church exists, and that true saints are living their holy, helpful lives, however shadowed and concealed. Even if the harvest of grain in any year is called a total loss, and the country never suffered so much before from dearth, there is always enough wheat or corn to plant the next spring, and the fewer handfuls the more precious it is sure to seem. In this eleventh century, a century which in many ways was so disorderly and cruel, we are always conscious of the presence of the "blameless knights" who went boldly to the fight; the priests and monks of God who hid themselves and prayed in cell and cloister. "It was feudal knighthood and Christianity together," says Guizot, "which produced the two great and glorious events of that time -- the Norman conquest of England, and the Crusades."

These were the knight's promises and oaths as Guizot repeats them, and we shall get no harm from reading them carefully and trying to keep them ourselves, even though all our battles are of another sort and much duller fights against temptations. It must be said that our enemies often come riding down upon us in as fine a way and break a lance with us in as magnificent a fashion as in the days of the old tournaments. But our contests are apt to be more like the ancient encounters with cruel treachery of wild beasts in desert places, than like those at the gay jousts, with all the shining knights and ladies looking on to admire and praise.

The candidates swore: First, to fear, reverence, and serve God religiously, to fight for the faith with all their might, and to die a thousand deaths rather than renounce Christianity;

To serve their sovereign prince faithfully, and to fight for him and fatherland right valiantly;

To uphold the rights of the weaker, such as widows, orphans, and damsels, in fair quarrel, exposing themselves on that account according as need might be, provided it were not against their own honor or against their king or lawful princes.

That they would not injure any one maliciously, or take what was another's, but would rather do battle with those who did so.

That greed, pay, gain, or profit should never constrain them to do any deed, but only glory and virtue.

That they would fight for the good and advantage of the common weal.

That they would be bound by and obey the orders of their generals and captains, who had a right to command them.

That they would guard the honor, rank, and order of their comrades, and that they would, neither by arrogance nor by force, commit any trespass against any one of them.

That they would never fight in companies against one, and that they would eschew all tricks and artifices.

That they would wear but one sword, unless they had to fight against two or more enemies.

That in tourney or other sportive contests, they would never use the point of their swords.

That being taken prisoner in a tourney, they would be bound on their faith and honor to perform in every point the conditions of capture, besides being bound to give up to the victors their arms and horses, if it seemed good to take them, being also disabled from fighting in war or elsewhere without their victor's leave.

That they would keep faith inviolably with all the world, and especially with their comrades, upholding their honor and advantage wholly in their absence.

That they would love and honor one another, and aid and succor one another whenever occasion offered.

That having made vow or promise to go on any quest or adventure, they would never put off their arms save for the night's rest.

That in pursuit of their quest or adventure, they would not shun bad and perilous passes, nor turn aside from the straight road for fear of encountering powerful knights, or monsters, or wild beasts, or other hindrance, such as the body and courage of a single man might tackle.

That they would never take wage or pay from any foreign prince.

That in command of troops or men-at-arms, they would live in the utmost possible order and discipline, and especially in their own country, where they would never suffer any harm or violence to be done.

That if they were bound to escort dame or damsel, they would serve, protect, and save her from all danger and insult, or die in that attempt.

That they would never offer violence to any dame or damsel, though they had won her by deeds of arms.

That being challenged to equal combat, they would not refuse without wound, sickness, or other reasonable hindrance.

That, having undertaken to carry out any enterprise, they would devote to it night and day, unless they were called away for the service of their king and country.

That, if they made a vow to acquire any honor, they would not draw back without having attained it or its equivalent.

That they would be faithful keepers of their word and pledged faith, and that, having become prisoners in fair warfare, they would pay to the uttermost the promised ransom, or return to prison at the day and hour agreed upon, on pain of being proclaimed infamous and perjured.

That, on returning to the court of their sovereign, they would render a true account of their adventures, even though they had sometimes been worsted, to the king and the registrar of the order, on pain of being deprived of the order of knighthood.

That, above all things, they would be faithful, courteous, and humble, and would never be wanting to their word for any harm or loss that might accrue to them.["]

It would not do to take these holy principles, or the pageant of knight-errantry, for a picture of Normandy in general. We can only remind ourselves with satisfaction that this leaven was working in the mass of turbulent, vindictive society. The priests worked very hard to keep their hold upon their people, and the authority of the church proved equal to many a subtle weakness of faith and quick strain of disloyalty. We should find it difficult to match the amazing control of the state by the church in any other country, -- even in the most superstitiously devout epochs. When the priesthood could not make the Normans promise to keep the peace altogether, they still obtained an astonishing concession and truce. There was no fighting from Wednesday evening at sunset until Monday morning at sunrise. During these five nights and four days no fighting, burning, robbing, or plundering could go on, though for the three days and two nights left of the week any violence and crime were not only pardonable, but allowed. In this Truce of God, not only the days of Christ's Last Supper, Passion, and Resurrection were to remain undesecrated, but longer periods of time, such as from the first day of Advent until the Epiphany, and other holy seasons. If the laws of the Truce were broken, there were heavy penalties: thirty years' hard penance in exile for the contrite offender, and he must make reparation for all the evil he had committed, and repay his debt for all the spoil. If he died unrepentant, he was denied Christian burial and all the offices of the church, and his body was given to wild beasts and the fowls of the air.

To be sure, the most ungodly portion of the citizens fought against such strict regulations, and called those knights whom the priests armed, "cits without spirit," and even harder names, but for twelve years the Truce was kept. The free days for murder and theft were evidently made the most of, and from what we can discover, it appears as if the Normans used the Truce days for plotting rather than for praying. Yet it was plain that the world was getting ready for great things, and that great emergencies were beginning to make themselves evident. New ideas were on the wing, and in spite of the despotism of the church, sometimes by very reason of it, we can see that men were breaking their intellectual fetters and becoming freer and wiser. A new order of things was coming in; there was that certain development of Christian ideas, which reconciles the student of history in every age to the constant pain and perplexity of watching misdirected energies and hindering blunders and follies.

"It often happens that popular emotions, however deep and general, remain barren, just as in the vegetable world many sprouts come to the surface of the ground, and then die without growing any more or bearing any fruit. It is not sufficient for the bringing about of great events and practical results, that popular aspirations should be merely manifested; it is necessary further that some great soul, some powerful will, should make itself the organ and agent of the public sentiment, and bring it to fecundity, by becoming its type -- its personification."*

In the middle of this eleventh century, the time of William the Conqueror's youth, the opposing elements of Christian knighthood, and the fighting spirit of the viking blood, were each to find a champion in the same leader. The young duke's early years were a hard training, and from his loveless babyhood to his unwept death, he had the bitter sorrows that belong to the life of a cruel man and much-feared tyrant. It may seem to be a strange claim to make for William the Conqueror -- that he represented Christian knighthood -- but we must remember that fighting was almost the first duty of man in those days, and that this greatest of the Norman dukes, with all his brutality and apparent heartlessness and selfishness, believed in his church, and kept many of her laws which most of his comrades broke as a matter of course. We cannot remind ourselves too often that he was a man of pure life in a most unbridled and immoral age, if we judge by our present standards of either purity or immorality. There is always a temptation in reading or writing about people who lived in earlier times, to rank them according to our own laws of morality and etiquette, but the first thing to be done is to get a clear idea of the time in question. The hero of Charlemagne's time or the Conqueror's may prove any thing but a hero in our eyes, but we must take him in relation to his own surroundings. The great laws of truth and justice and kindness remain, while the years come and go; the promises of God endure, but while there is, as one may say, a common law of heavenly ordering, there are also the various statute laws that vary with time and place, and these forever change as men change, and the light of civilization burns brighter and clearer.

In William the Conqueror's lifetime, every landed gentleman fortified his house against his neighbors, and even made a secure and loathsome prison in his cellar for their frequent accommodation. This seems inhospitable, to say the least, and gives a tinge of falseness to such tender admonitions as prevailed in regard to charity and treatment of wayfarers. Yet every rich man was ambitious to go down to fame as a benefactor of the church; all over Normandy and Brittany there was a new growth of religious houses, and those of an earlier date, which had lain in ruins since the Northmen's time, were rebuilt with pious care. There appears to have been a new awakening of religious interest in the year 1000, which lasted late into the century. There was a surprising fear and anticipation of the end of the world, which led to a vast number of penitential deeds of devotion, and it was the same during the two or three years after 1030, at the close of the life of King Robert of France.

Normandy and all the neighboring countries were scourged by even worse plagues than the feudal wars. The drought was terrible, and the famine which followed desolated the land everywhere. The trees and fields were scorched and shrivelled, and the poor peasants fought with the wild beasts for dead bodies that had fallen by the roadside and in the forests. Sometimes men killed their comrades for very hunger, like wolves. There was no commerce which could supply the failure of one country's crops with the overflow of another's at the other side of the world, but at last the rain fell in France, and the misery was ended. A thousand votive offerings were made for very thankfulness, for again the people had expected the end of the world, and it had seemed most probable that such an arid earth should be near its final burning and desolation.

In the towns, under ordinary circumstances, there was a style of living that was almost luxurious. The Normans were skilful architects, and not only their ministers and monasteries, but their houses too, were fit for such proud inhabitants, and rich with hangings and comfortable furnishings. The women were more famous than ever for needlework, some of it most skilful in design, and the great tapestries are yet in existence that were hung, partly for warmth's sake, about the stone walls of the castles. Sometimes the noble ladies who sat at home while their lords went out to the wars, worked great pictures on these tapestries of various events of family history, and these family records of battles and gallant bravery by land and sea are most interesting now for their costume and color, beside their corroboration of historical traditions.

We have drifted away, in this chapter, from William the Conqueror himself, but I believe that we know more about the Normandy which he was to govern, and can better understand his ambitions, his difficulties, and his successes. A country of priests and soldiers, of beautiful women and gallant men; a social atmosphere already alive with light, gayety, and brightness, but swayed with pride and superstition, with worldliness and austerity; loyal to Rome, greedy for new territory, the feudal lords imperious masters of complaining yet valiant serfs; racked everywhere by civil feuds and petty wars and instinctive jealousies of French and foreign blood -- this was Normandy. The Englishmen come and go and learn good manners and the customs of chivalry, England herself is growing rich and stupid, for Harthacnut had introduced a damaging custom of eating four great meals a day, and his subjects had followed the fashion, though that king himself had died of it and of his other habit of drinking all night long with merry companions.

Jewett's Notes

Johnson: "The Normans in Europe."**

Guizot.**

Notes for Chapter 8

Tennyson: These lines end the poem, "Ulysses," by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892).

[ Back ]

History of France: Jewett indicates that she takes her material on knighthood from François M. Guizot (1787–1874) and Madame Elizabeth de Witt, The History of France from the earliest times to 1848, Volume 1 (1885). (See Jewett's Sources).

The knight's oaths are on pp. 260-2.

The description of the ceremony of investiture appears on pp. 258-9. Jewett adapts her description from this one, and probably not from Guizot's The History of France from the Earliest Times to the Outbreak of the Revolution (1879), p. 66.

"It often happens that popular emotions, ...": The quotation she attributes to Guizot in her final note appears on p. 304.

It may be worth noting that E. A. Freeman, Jewett's most authoritative source on Norman history, held an apparently opposing view to Jewett, characterizing chivalry as a false ideal that ultimately harmed the development of social justice in western Europe by placing personal honor above communal well-being in the ruling class (vol. 5, pp. 323-5).

[ Back ]

Abelard and St. Anselm: According to Wikipedia, Peter Abelard (1079-1142) "was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, theologian and preeminent logician." St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) "also called Anselm of Aosta for his birthplace, and Anselm of Bec for his home monastery, was a Benedictine monk, philosopher, and prelate of the Church, who held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109."

[ Back ]

cits without spirit: Webster's 1913 dictionary says that "cit" is an abbreviation for "citizen," and often is derogatory. This seems an odd term to apply to knights, whatever their source of authority. No source has been located for this quotation. Further clarification is welcome.

[ Back ]

Jewett's Notes

Johnson: Jewett's quotation about William appears in A. H. Johnson, The Normans in Europe, pp. 86-7. (See Jewett's Sources.)

[ Back ]

Guizot: See History of France above.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College, with assistance from Allison Anderson and Gabe Heller.

.