The Normans

by Sarah Orne Jewett

Chapter XII.

MATILDA OF FLANDERS.

"It had been easy fighting in some plain,

Where victory might hang in equal choice;

But all resistance against her is vain."

- Marvell.We have occasionally had a glimpse of Flanders and its leading men in the course of our Norman story; but now the two dukedoms were to be linked together by a closer tie than either neighborhood, or a brotherhood, or antagonism in military affairs. While Normandy had been gaining new territory and making itself more and more feared by the power of its armies, and had been growing richer and richer with its farms and the various industries of the towns, Flanders was always keeping pace, if not leading, in worldly prosperity.

Flanders had gained the dignity and opulence of a kingdom. Her people were busy, strong, intelligent craftsmen and artists, and while her bell-towers lifted themselves high in the air, and made their chimes heard far and wide across the level country, the weavers' looms and the women's clever fingers were sending tapestries to the walls of the Vatican, and frost-like laces to the ladies of Spain.

The heavy ships of Flanders went and came with the richest of freights from her crowded ports; her picture-painters were at work, her gardens were green, and her noblemen's houses were filled with whatever a luxurious life could demand or invent. As the country became overcrowded, many of the inhabitants crossed over to Scotland, and gained a foot-hold, sometimes by the sword, and oftener by the plough and spade and weaver's shuttle. The Douglases and the Leslies, Robert Bruce and all the families of Flemings, took root then, and, whether by art or trade, established a right to be called Scotsmen, and to march in the front rank when the story is told of many a brave day in Scottish history.

The Count of Flanders was nominally vassal of both Rome and France, but he was practically his own man. Baldwin de Lisle, of the Conqueror's time, was too great a man to need anybody's help, or to be bought or sold at will by an over-lord. He stood well as the representative of his country's wealth and dignity. A firm alliance with such a neighbor was naturally coveted by such a far-seeing man as the young duke; and besides any political reasons, there was a closer reason still, in the love that had sprung up in his heart for Matilda, the count's daughter. In 1049, he had been already making suit for her hand, for it was in that year when the Council of Rheims forbade the banns, on some plea of relationship that was within the limit set by the Church. William's whole existence was a fight for his life, for his dukedom, for his kingdom of England, and he was not wanting in courage in this long siege of church and state, when the woman he truly loved was the desired prize. If history can be trusted, she was a prize worth winning; if William had not loved her, he would not have schemed and persisted for years in trying to win her in spite of countless hindrances which might well have ended his quest if he had been guided only by political reasons for the alliance.

His nobles had eagerly urged him to marry. Perhaps they would have turned their eyes toward England first if there had been a royal princess of Eadward's house, but failing this, Flanders was the best prize. The Norman dukedom must not be left without an heir, and this time there must be no question of the honesty of the heir's claim and right to succession. Normandy had seen enough division and dissension, and angry partisanship during the duke's own youth, and now that he had reached the age of twenty-four, and had made himself master of his possessions, and could take his stand among his royal neighbors, everybody clamored for his marriage, and for a Lady of Normandy. He was a pure man in that time of folly and licentiousness. He was already recognized as a great man, and even the daughter of Baldwin of Flanders might be proud to marry him.

Matilda was near the duke's own age, but she had already been married to a Flemish official, and had two children. She was a beautiful, graceful woman, and it is impossible to believe some well-known old stories of William's rude courtship of her, since her father evidently was ready to favor the marriage, and she seems to have been a most loyal and devoted wife to her husband, and to have been ready enough to marry him hastily at the end of a most troublesome courtship. The great Council of Rheims had forbidden their marriage, as we have already seen, and the pious Pope Leo had struck blows right and left among high offenders of the Church's laws; a whole troop of princes were excommunicated or put under heavy penances, and the Church's own officials were dealt justly with according to their sins. When most of these lesser contemporaries were properly sentenced, a decree followed, which touched two more illustrious men: the Count of Flanders was forbidden to give his daughter to the Norman duke for a wife, and William, in his turn, was forbidden to take her. For four long years the lovers -- if we may believe them to be lovers -- were kept apart on the Pope's plea of consanguinity. There is no evidence remaining that this was just, yet there truly may have been some relationship. It is much easier to believe it, at any rate, than that the count's wife Adela's former child-marriage to William's uncle could have been put forward as any sort of objection.

We must leave for another chapter the affairs of Normandy and William's own deeds during the four years, and go forward with this story of his marriage to a later time, when in the course of Italian affairs, a chance was given to bring the long courtship to a happy end. Strangely enough this came by means of the De Hautevilles and that Norman colony whose fortunes we have already briefly traced. In the conflict with Pope Leo, when he was forced to yield to the Normans' power and to recognize them as a loyal state, William either won a consent to his wedding or else dared to brave the Pope's disapproval. While Leo was still in subjection the eager duke hurried to his city of Eu, near the Flemish border, and met there Count Baldwin and his daughter. There was no time spent in splendid processions and triumphal pageants of the Flemish craftsmen; some minor priest gave the blessing, and as the duke and his hardly-won wife came back to the Norman capital there was a great cheering and rejoicing all the way; and the journey was made as stately and pompous as heart could wish. There was a magnificent welcome at Rolf's old city of Rouen; it was many years since there had been a noble lady, a true duchess, on the ducal throne of Normandy.

But the spirit of ecclesiasticism held its head too high in the pirates' land to brook such disregard of its canons, even on the part of its chief ruler. There was an uncle of William's, named Mauger, who was primate of the Norman church. He is called on every hand a very bad man -- at any rate, his faults were just the opposite of William's, and of a sensual and worldly stamp. He was not a fit man for the leader of the clergy, in William's opinion. Yet Mauger was zealous in doing at least some of the duties of his office -- he did not flinch from rebuking his nephew! All the stories of his life are of the worst sort, unless we give him the credit of trying to do right in this case, but we can too easily remember the hatred that he and all his family bore toward the bastard duke in his boyhood, and suspect at least that jealousy may have taken the place of scorn and despising. One learns to fear making point-blank decisions about the character of a man so long dead, even of one whom everybody blamed like Mauger. His biographers may have been his personal enemies, and later writers have ignorantly perpetuated an unjust hue and cry.

Perhaps Lanfranc may be trusted better, for he too blamed the duke for breaking a holy law, -- Lanfranc the merry, wise Italian, who loved his fellow-men, and who was a teacher by choice and by gift of God. All Normandy was laid under a ban at this time for the wrong its master had done. Lanfranc rebuked the assumed sinner bravely, and William's fierce stern temper blazed out against him, and ordered a vicious revenge of the insult to him and to his wife. The just William, who kept Normandy in such good order, who stood like a bulwark of hewn stone between his country and her enemies, was the same William who could toss severed hands and feet over the Alençon wall, and give orders to burn the grain stacks and household goods of the abbey of Bec. We have seen how the duke and the abbot met, and how they became friends again, and Lanfranc made peace with Pope Leo and won him the loyalty of Normandy in return. Very likely Lanfranc was glad to explain the truth and to be relieved from upholding such a flimsy structure as the church's honor demanded. At any rate, William gladly paid his Peter's pence and set about building his great abbey of St. Etienne, in Caen, for a penance, and made Lanfranc its prelate, and Matilda built her abbey of the Holy Trinity, while in four of the chief towns of Normandy hospitals were built for the old and sick people of the duchy. We shall see more of these churches presently, but there they still stand, facing each other across the high-peaked roofs of Caen; high and stately churches, the woman's tower and the man's showing characteristics of boldness and of ornament that mark the builders' fancy and carry us in imagination quickly back across the eight hundred years since they were planned and founded. Anselm, Maurilius, and Lanfranc, these were the teachers and householders of the great churches, and one must have a new respect for the young duke and duchess who could gather and hold three such scholars and saintly men to be leaders of the church in Normandy.

There were four sons and three daughters born to William and Matilda, and there is no hint of any difference or trouble between the duke and his wife until they were unable to agree about the misconduct of their eldest son. Matilda's influence for good may often be traced or guessed at in her husband's history, and there are pathetic certainties of her resignation and gentleness when she was often cruelly hurt and tried by the course of events.

Later research has done away with the old idea of her working the famous Bayeux tapestry with the ladies of her court to celebrate the Conqueror's great deeds; but he needed no tribute of needle-work, nor she either, to make them remembered. They have both left pictures of themselves done in fadeless colors and living text of lettering that will stand while English words are spoken, and Norman trees bloom in the spring, and Norman rivers run to the sea, and the towers of Caen spring boldly toward the sky.

We cannot be too thankful that so much of these historic churches has been left untouched. When it is considered that at five separate times the very fiends of destruction and iconoclasm seem to have been let loose in Normandy, it is a great surprise that there should be so many old buildings still in existence. From the early depredations of the Northmen themselves, down to the religious wars of the sixteenth century and the French revolution of the eighteenth, there have been other and almost worse destroying agencies than even the wars themselves. Besides the natural decay of masonry and timber, there was the very pride and growing wealth of the rich monastic orders and the large towns, who liked nothing better than to pull down their barns to build greater and often less interesting ones. The most prosperous cities naturally build the best churches, as they themselves increase, and naturally replace them oftenest, and so retain fewest that are of much historical interest in the end. The most popular weapon in the tenth and eleventh centuries was fire; and the first thing that Norman assailants were likely to do, was to throw burning torches over the walls into the besieged towns. Again and again they were burnt -- houses, churches, and all.

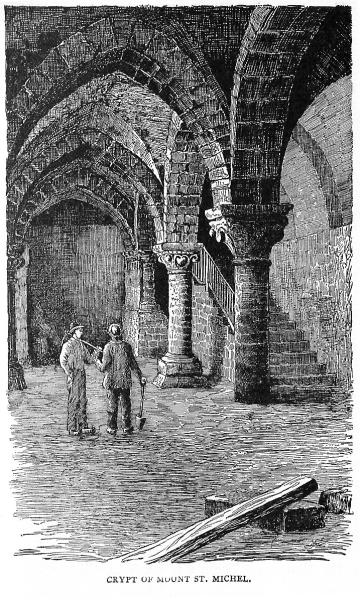

The Normans were constantly improving, however, in their fashions of building, and had made a great advance upon the Roman architecture which they had found when they came to Neustria. Their work has a distinct character of its own, and perhaps their very ignorance of the more ornate and less effective work which had begun to prevail in Italy, gave them freedom to work out their own simple ideas. Instead of busying themselves with petty ornamentation and tawdry imagery, they trusted for effect to the principles of height and size. Their churches are more beautiful than any in the world; their very plainness and severity gives them a beautiful dignity, and their slender pillars and high arches make one think of nothing so much as the tall pine forests of the North. What the Normans did with the idea of the Roman arch, they did too in many other ways. They had a gift of good taste that was most exceptional in that time, and especially in that part of Europe; and whatever had been the power and efficiency of the last impulse of civilization from the South, this impulse from the North did a noble work in its turn. Normandy herself, in the days of William and Matilda, was fully alive and pervaded with dreams of growth and expansion.

Nobody can tell how early the idea of the conquest of England began to be a favorite Norman dream. In those days there was always a possibility of some day owning one's neighbors land, and with weak Eadward on the throne of England, only too ready to listen to the suggestions and demands of his Norman barons and favorite counsellors, it must have seemed always an easier, not to say more plausible, thing to take one step farther. There was an excellent antechamber across the Channel for the crowded court and fields of Normandy, and William and Eadward were old friends and companions. In 1051, when Normandy was at peace, and England was at any rate quiet and sullen, submissive to rule, but lying fast, bound like a rebellious slave that has been sold to a new master, William and a fine company of lords and gentlemen went a-visiting.

All those lords and gentlemen kept their eyes very wide open, and took good notice of what they saw.

It was not a common thing by any means, for a great duke to go pleasuring. He was apt to be too busy at home; but William's affairs were in good order, and his cousin of England was a feeble man and more than half a Norman; besides, he had no heir, and in course of time the English throne would lack a proper king. The idea of such a holiday might have pleased the anxious suitor of Matilda of Flanders, too, and have beguiled the hard time of waiting. Nobody stopped to remember that English law gave no right of succession to mere inheritance or descent. Ralph the Timid was Æthelred's grandson; but who would think of making him king instead of such a man as William? The poor banished prince at the Hungarian court, half a world away, was not so much as missed or wished for. Godwine was banished, Harold was in Ireland; besides, it must be urged that there was something fine in the notion of adding such a state as Normandy to England. England was not robbed, but magnificently endowed by such a proposal.

Eadward was amiably glad to see this brave Duke of the Normans. There was much to talk over together of the past; the present had its questions, too, and it was good to have such a strong arm to lean upon; what could have been more natural than that the future also should have its veil drawn aside, not too rashly or irreverently? When Eadward had been gathered to his fellow saints, pioneered by visions that did not fade, and panoplied by authentic relics -- nay, when the man of prayers and cloistered quietness was kindly taken away from the discordant painfulness of an earthly kingdom, what more easy than to dream of this warlike William in his place; William, a man of war and soldiery, for whom the government of two great kingdoms in one, would only harden and employ the tense muscles and heavy brain; would only provide his own rightful business? And, while Eadward thought of this plan, William was Norman, too, and with the careful diplomacy of his race, he joined the daring and outspokenness of old Rolf the Ganger; he came back with his lords and gentlemen to Normandy, weighed down with presents -- every man of them who had not stayed behind for better gain's sake. He came back to Normandy the acknowledged successor to the English crown. Heaven send dampness now and bleak winds, and let poor Eadward's sufferings be short! There was work for a man to do in ruling England, and Eadward could not do it. The Englishmen were stupid and dull; they ate too much and drank too much; they clung with both hands to their old notions of state-craft and government. It was the old story of the hare and the tortoise, but the hare was fleet of foot and would win.

Win? Yes, this race and that race; and yet the tortoise was going to be somehow made over new, and keep a steady course in the right path, and learn speed, and get to be better than the old tortoise as the years went on and on.

Eadward had no right to will away the kingship of England; but this must have been the time of the promise that the Normans claimed, and that their chroniclers have recorded. All Normandy believed in this promise, and were ready to fight for it in after years. It is most likely that Eadward was only too glad, at this date, to make a private arrangement with the duke. He was on the worst of terms just then with Godwine and his family, and consequently with the displeased English party, who were their ardent upholders. Indeed, a great many of these men were in Ireland with Harold, having turned their backs upon a king and court that were growing more friendly to Normandy and disloyal to England day by day.

The very next year after William's triumphal visit the Confessor was obliged to change his course in the still stormier sea of English politics. The Normans had shown their policy too soon, and there was a widespread disapproval, and an outcry for Godwine's return from exile. Baldwin of Flanders, and King Henry of France, had already been petitioning for his pardon, and suddenly Godwine himself came sailing up the Thames, and London eagerly put itself under his control. Then Eadward the Confessor consented to a reconciliation, there being no apparent alternative, and a troop of disappointed and displaced foreigners went back to Normandy. Robert of Jumièges, was among them. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle tells us gravely, that at Walton-on-the-Naze, "they were lighted on a crazy ship, and the archbishop betook himself at once over the sea, leaving behind him his pall and all his christendom here in the land even as God willed it, because he had taken upon him that worship as God willed it not." The plea for taking away his place was "because he had done more than any to cause strife between Godwine and the king"; and Godwine's power was again the strongest in England.

The great earl lived only a few months longer, and when he died his son Harold took his place. Already the eyes of many Englishmen were ready to see in him their future king. Already he stands out a bold figure, with a heart that was true to England, and though the hopes that centred in him were broken centuries ago, we cannot help catching something of the hope and spirit of the time. We are almost ready to forget that this brave leader, the champion of that elder English people, was doomed to fall before the on-rushing of a new element of manhood, a tributary stream that came to swell the mighty channel of the English race and history. William the Norman was busy at home, meanwhile. The old hostility between Normandy and Flanders, which dated from the time of William Longsword's murder, was now at a certain end, by reason of the duke's marriage. Matilda, the noble Flemish lady, the descendant of good King Ælfred of England, had brought peace and friendliness as not the least of her dowry, and all fear of any immediate antagonism from that quarter was at an end.

By the alliance with the kings of France, the Norman dukes had been greatly helped to gain their present eminence, and to the Norman dukes the French kings, in their turn, owed their stability upon their own thrones; they had fought for each other and stood by each other again and again. Now, there was a rift between them that grew wider and wider -- a rift that came from jealousy and fear of the Normans' wealth and enormous growth in strength. They were masters of the Breton country, and had close ties of relationship, moreover, with not only Brittany, but with Flanders and the smaller county of Ponthieu, which lay between them and the Flemings. Normandy stretched her huge bulk and strength between France and the sea; she commanded the French rivers, the French borders; she was too much to be feared; if ever her pride were to be brought down, and the old vassalage insisted upon, it could not be too soon. Henry forgot all that he owed to the Normans' protection, and provoked them by incessant hostilities -- secret and open treacheries, -- and the fox waged war upon the lion, until a spirit of enmity was roused that hardly slept again for five hundred years.

There were other princes ready enough to satisfy their fear and jealousy. The lands of the conspirators stretched from Burgundy to the Pyrenees. Burgundy, Blois, Ponthieu, Aquitaine, and Poitiers all joined in the chase for this William the Bastard, the chief of the hated pirates. All the old gibes and taunts, and contemptuous animosity were revived; now was the time to put an end to the Norman's outrageous greed of power and insolence of possession, and the great allied army divided itself in two parts, and marched away to Normandy.

King Henry's brother, Odo, turned his forces toward Rouen, and the king himself took a more southerly direction, by the way of Lisieux to the sea. They meant, at any rate, to pen the duke into his old Danish region of the Côtentin and Bessin districts; all his eastern lands, the grant from Charles the Simple, with the rest, were to be seized upon and taken back by their original owners.

Things had changed since the battle of Val-ès-dunes. There was no division now among the Norman lords, and as the word to arm against France was passed from one feudal chieftan to another, there was a great mustering of horse and foot. So the king had made up his mind to punish them, and to behave as if he had a right to take back the gift that was unwillingly rung from Charles the Simple. Normandy is our own, not Henry's, was the angry answer; and Ralph of Tesson, and the soldiers of Falaise, the Lord of Mortain, the men of Bessin, and the barons of the Côtentin were ready to take the field, and stand shoulder to shoulder. There had been a change indeed, in Normandy; and from one end of it to the other there was a cry of shame and treachery upon Henry, the faithless ally and overlord. They had learned to know William as a man not against their interests but with them, and for them and the glory of Normandy; and they had not so soon forgotten the day of Val-ès-dunes and their bitter mistake.

The king's force had come into the country by the frontier city of Aumale, and had been doing every sort of damage that human ingenuity could invent between conqueror and vanquished. It was complained by those who escaped that the French were worse than Saracens. Old people, women, and children were abused or quickly butchered; men were taken prisoners; churches and houses were burnt or pulled to pieces. There was a town called Mortemer which had the ill-luck to be chosen for the French head-quarters, because it was then a good place for getting supplies and lodging, though now there is nothing left of it but the remains of an ancient tower and a few dwellings and gardens. Here the feasting and revelry went on as if Normandy were already fallen. All day there were raids in the neighboring country, and bringing in of captives, and plunder; and William's spies came to Mortemer, and went home to tell the duke the whole story of the hateful scene. There was a huge army collected there fearless of surprise; this was the place to strike a blow, and the duke and his captains made a rapid march by night so that they reached Mortemer before daylight.

There was no weapon more cherished by the pirates' grandchildren than a blazing fire-brand, and the army stole through the town while their enemies still slept, stupid with eating and drinking, or weary from the previous day's harrying. They waked to find their houses in flames, the roofs crackling, a horrid glare of light, a bewilderment of smoke and shouts; the Normans ready to kill, to burn, to pen them back by sturdy guards at the streets' ends. There was a courageous resistance to this onslaught, but from early morning until the day was well spent the fight went on, and most of the invaders were cut to pieces. The dead men lay thick in the streets, and scattered everywhere about the adjacent fields. "Only those were spared who were worth sparing for the sake of their ransom. Many a Norman soldier, down to the meanest serving-man in the ranks, carried off his French prisoner; many a one carried off his two or three goodly steeds with their rich harness. In all Normandy there was not a prison that was not full of Frenchmen."* All this was done with scarcely any loss to the Normans, at least so we are told, and the news came to William that same evening, and made him thank God with great rejoicing. It would seem as if only a God of battles could be a very near and welcome sovereign to this soldier-lord of Normandy.

The victor had still another foe to meet. The king's command was still to be vanquished, and perhaps it might be done with even less bloodshed. The night had fallen, and he chose Ralph of Toesny, son of that Roger who sought the Spanish kingdom, the enemy of his own ill-championed childhood, to go as messenger to the king's tent. The two chieftains cannot have been encamped very far apart, for it was still dark when Ralph rode fast on his errand. He crept close to where the king lay in the darkness, and in the glimmer of dawn he gave a doleful shout: "Wake, wake, you Frenchmen! You sleep too long; go and bury your friends who lie dead at Mortemer"; then he stole away again unseen, while the startled king and his followers whispered together of such a terrible omen. Ill news travels apace; they were not long in doubt; a panic seized the whole host. Not for Rouen now, or the Norman cities, but for Paris the king marched as fast as he could go; and nobody gave him chase, so that before long he and his counts were safe at home again with the thought of their folly for company. Craft is not so fine a grace as courage; but craft served the Normans many a good turn; and this was not the least glorious of William's victories, though no blood was spilt, though the king was driven away and no sword lifted to punish him. The Normans loved a bit of fun; we can imagine how well they liked to tell the story of spoiling half an army with hardly a scratch for themselves, and making the other half take to its heels at the sound of Ralph de Toesny's gloomy voice in the night. There were frequent hostilities after this along the borders, but no more leagues of the French counts; there was a castle of Breteuil built to stand guard against the king's castle of Tillières, and William Fitz-Osbern was made commander of it; there was an expedition of the Count of Maine, aided by Geoffrey Martel and a somewhat unwilling Breton prince, against the southern castle of Ambrières. But when William hastened to its relief the besiegers took to flight, except the Lord of Maine, who was captured and put into prison until he was willing to acknowledge himself the duke's vassal; and after this there were three years of peace in Normandy.

It had grown to be a most orderly country. William's famous curfew bell was proved to be an efficient police force. Every household's fire was out at eight o'clock in winter, and sunset in summer, and its lights extinguished; every man was in his own dwelling-place then under dire penalty; he was a strict governor, but in the main a just one -- this son of the lawless Robert. He upheld the rights of the poor landholders and widows, and while he was feared he was respected. It was now that he gave so much thought to the rights of the Church, or the following out of his own dislike, in the dismissal of his Uncle Mauger, the primate of the duchy.

There is still another battle to be recorded in this chapter, -- one which for real importance is classed with the two famous days of Val-ès-dunes and Hastings, -- the battle fought at Varaville, against the French king and his Angevine ally, who took it into their silly heads to go a-plundering on the duke's domain.

Bayeux and Caen were to be sacked, and all the surrounding country; besides this, the allies were going to march to the sea to show the Bastard that he could not lock them up in their inland country and shake the key in their faces. William watched them as a cat watches a mouse and lets the poor thing play and feast itself in fancied security. He had the patience to let the invaders rob and burn, and spoil the crops; to let them live in his towns, and the French king himself hold a temporary court in a fine new abbey of the Bessin, until everybody thought he was afraid of this mouse, and that all the Normans were cowards; then the quick, fierce paw struck out, and the blow fell. It is a piteous story of war, that battle of Varaville!

There was a ford where the French, laden with their weight of spoils, meant to cross the river Dive into the district of Auge. On the Varaville side the land is marshy; across the river, and at no great distance, there is a range of hills which lie between the bank of the Dive and the rich country of Lisieux. The French had meant to go to Lisieux when they started out on their other enterprise. But William had waited for this moment; part of the army under the king's command had crossed over, and were even beginning to climb the hills. The rear-guard with the great baggage trains were on the other bank, when there was a deplorable surprise. William, with a body of trained troops, had come out from Falaise; he had recruited his army with all the peasants of the district; armed with every rude weapon that could be gathered in such haste, they were only too ready to fall upon the French mercilessly.

The tide was flowing in with disastrous haste, and the Frenchmen had not counted upon this awful foe. Their army was cut in two; the king looked down in misery from the height he had thoughtlessly gained. Now we hear almost for the first time of that deadly shower of Norman arrows, famous enough since in history. Down they came with their sharp talons; the poor French were huddling together at the river's brink; there was no shelter; the bowmen shot at them; the peasants beat them with flails and scythes; into the rushing water they went, and floated away writhing. There was not a man left alive in troop after troop, and there were men enough of the Normans who knew the puzzling, marshy ground to chase and capture those other troopers who tried to run away. Alas for the lilies of France! how they were trailed in the mire of that riverside at Varaville! It was a massacre rather than a battle, and Henry's spirit was humbled. "Heavy-hearted, he never held spear or shield again," says the chronicle. There were no more expeditions against Normandy in his time; he sued for a truce, and paid as the price for it, the castle of Tillières, and so that stronghold came back to its rightful lords again. Within two years he died, being an old man, and we can well believe a disappointed one. Geoffrey Martel died too, that year, the most troublesome of the Bastard's great neighbors. This was 1060; and it was in that year that Harold of England first came over to Normandy -- an unlucky visit enough, as time proved. His object was partly to take a look at the political state of Gaul; but if he meant to sound the hearts of the duke's neighbors in regard to him, as some people have thought, he could not have chosen a more unlucky time. If he meant to speak for support in case William proved to be England's enemy in days to come, he was too late; those who would have been most ready to listen were beyond the reach of human intrigues, and their deaths had the effect of favoring William's supremacy, not disputing it.

There is no record of the great earl's meeting the Norman duke at all on their first journey. If we had a better account of it, we might solve many vexed questions. Some scholars think that it was during this visit that Harold was inveigled into taking oath to uphold William's claim to the English crown, but the records nearly all belong to the religious character of the expedition. Harold followed King Cnut's example in going on a pilgrimage to Rome, and brought back various treasures for his abbey of Waltham, the most favored religious house of his earldom. He has suffered much misrepresentation, no doubt, at the hands of the monkish writers, for he neglected their claims in proportion as he favored their secular brethren, for whom the abbey was designed. A monk retired from the world for the benefit of his own soul, but a priest gave his life in teaching and preaching to his fellow-men. We are told that Harold had no prejudice against even a married priest, and this was rank heresy and ecclesiastical treason in the minds of many cloistered brethren.

Notes for Chapter 12

all resistance against her is vain: from "The Fair Singer" (1681), by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678).

[ Back ]

Anselm, Maurilius, and Lanfranc: Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) was Archbishop of Canterbury (1093-1109). Maurilius (c. 1000–1067) was a Norman Archbishop of Rouen from 1055 to 1067. Lanfranc is introduced by Jewett in Chapter 11. For further information about these Norman clerics, see Wikipedia: Anselm, Maurilius, Lanfranc.

[ Back ]

were lighted on a crazy ship: This story is recounted in Freeman, vol. 2, pp. 218-9, but Jewett does not seem to have quoted from him. It appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 152, but not exactly as Jewett quotes. She seems to quote from the same translation as Johnson, p. 116, or perhaps from Guest, p. 131. See Jewett's Sources.

[ Back ]

never held spear or shield again: Jewett draws this story from Master Wace, p. 62, but does not quote from the available translation. See Jewett's Sources.

[ Back ]

Jewett's Note

Freeman: "In all Normandy there was not a prison that was not full of Frenchmen": This passage in in Freeman, vol. 3, p. 105. See Jewett's Sources.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College, with assistance from Allison Anderson and Gabe Heller.