| Return to The Normans |

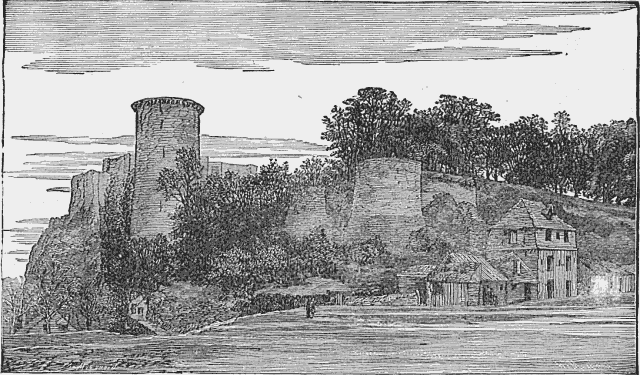

Frontispiece. Birthplace of William the Conqueror. Palaise.

"Then in his house of wood with flaxen sails

She floats, a queen, across the fateful seas." -- A. F.

Rather than follow in detail the twenty-one years of William's English reign, we must content ourselves with a glance at the main features of it. We cannot too often remind ourselves of the resemblance between the life and growth of a nation and the life and growth of an individual; but while William the Conqueror is in so many ways typical of Normandy, and it is most interesting to follow his personal fortunes, there are many developments of Norman character in general which we must not overlook. William was about forty years old when the battle of Hastings was fought and won; Normandy, too, was in her best vigor and full development of strength. The years of decadence must soon begin for both; the time was not far distant when the story of Normandy ends, and it is only in the history of France and of England that the familiar Norman characteristics can be traced. Foremost in vitalizing force and power of centralization and individuality, while so much of Europe was unsettled and misdirected toward petty ends, this duchy of Rolf the Ganger seems, in later years, like a wild-flower that has scattered its seed to every wind, and plants for unceasing harvests, but must die itself in the first frost of outward assailment and inward weakness.

The march to London had been any thing but a triumphant progress, and the subjects of the new king were very sullen and vindictive. England was disheartened, her pride was humbled to the dust, and many of her leaders had fallen. In the dark winter weather there was sorrow and murmuring; the later law of the curfew bell, a most wise police regulation, made the whole country a prison.

A great deal of harrying had been thought necessary before the people were ready to come to William and ask him to accept the crown. William had a great gift for biding his time, and in the end the crown was proffered, not demanded. We learn that the folk thought better of their conqueror at last, that Cnut was remembered kindly, and the word went from mouth to mouth that England might do worse than take this famous Christian prince to rule over her. Harold had appealed to heaven when the fight began at Senlac, but heaven had given the victory to other hands. The northern earls had forsaken them, and at any rate the Norman devastations must be stopped. If William would do for England what he had done for his own duchy and make it feared for valor and respected for its prosperity like Normandy, who could ask more? So the duke called a formal council of his high noblemen and, after careful consideration, made known his acceptance! There was a strange scene at the coronation in Westminster. Norman horsemen guarded the neighboring streets, a great crowd of spectators filled the church, and when the question was put to this crowd, whether they would accept William for their king, there was an eager shout of "Yea! yea! King William!" Perhaps the Normans had never heard such a noisy outcry at a solemn service. Again the shout was heard, this time the same question had been repeated in the French tongue, and again the answer was "Yea! yea!"

The guards outside thought there was some treachery within, and feared that harm might come to their leader, so, by way of antidote or revenge, they set fire to the buildings near the minster walls. Out rushed the congregation to save their goods or, it might be, their lives, while the ceremony went on within, and the duke himself trembled with apprehension as he took the solemn oath of an English king, to do justice and mercy to all his people. There was a new crown to be put on, -- what had become of the Confessor's? -- but at last the rite was finished and William, king of the English, with his priests and knights, came out to find a scene of ruin and disorder; it was all strangely typical -- the makeshift splendors, the new order of church and state, the burning hatred and suspicions of that Christmastide. Peace on earth, good-will to men! alas, it was any thing but that in the later years of William's reign.

No doubt he built high hopes and made deep plans for good governance and England's glory. He had tamed Normandy to his guiding as one tames a wild and fiery horse, and there seemed to be no reason why he could not tame England. In the beginning he attempted to prove himself lenient and kind, but such efforts failed; it was too plain that the Normans had captured England and meant to enjoy the spoils. The estates belonging to the dead thanes and ealdormen, who fought with Harold, were confiscated and divided among the Normans: this was the fortune of war, but it was a bitter grievance and injustice. O, for another Godwine! cried many a man and woman in those days. O, for another Godwine to swoop down upon these foreign vultures who are tearing at England's heart! But even in the Confessor's time there was little security for private property. We have even seen the Confessor's own wife banished from his side without the rich dowry she had brought him, and Godwine's estates had been seized and refunded again, as had many another man's in the reign of that pious king whom everybody was ready to canonize and deplore.

After the king had given orders to his army to stop plundering and burning, there was a good deal of irregular depredation for which he was hardly responsible. He was really king of a very small part of England. The army must not be disbanded, it must be kept together for possible defence, but the presence of such a body of rapacious men, who needed food and lodging, and who were not content unless they had some personal gain from the rich country they had helped to win, could not help being disastrous. Yet there is one certain thing -- the duke meant to be master of his new possessions, and could use Englishmen to keep his Norman followers in check, while he could indulge his own countrymen in their love of power and aggrandizement at England's expense. There are touching pictures of his royal progress through the country in the early part of his reign; the widows of thanes and the best of the churls would come out with their little children, to crave mercy and the restitution of even a small part of their old estates to save them from beggary. Poor women! it was upon them that the heaviest burden fell; the women of a war-stricken country suffer by far the most from change and loss; not the heroes who die in battle, or the heroes who live to tell the story of the fight, and who have been either victors or vanquished. Men are more reasonable; they have had the recompense of taking part in the struggle. If they have been in the wrong or in the right, great truths have come home to them as they stood sword in hand.

The Norman barons, who had followed their leader beyond the Channel, had been won by promises, and these promises must be kept. They were made rich with the conquered lands, and given authority, one would think, to their heart's content. They were made the king's magistrates and counsellors, and as years went by there was more and more resentment of all this on the part of the English. They hated their Norman lords; they hated the taxes which the king claimed. The strong point of the Saxon civilization was local self-government and self-dependence; but the weak point was the lack of unity and want of proper centralization and superintendence. William was wise in overcoming this; instead of giving feudalism its full sway and making his Norman barons petty monarchs with right of coinage and full authority over their own dominion, he claimed the homage and loyalty, the absolute allegiance of his subjects. But for his foresight in making such laws, England might have been such a kingdom as Charles the Simple's or Hugh Capet's, and hampered with feudal lords greater than their monarch in every thing but name.

In England, at last, every man held his land directly from the king and was responsible to him. The Witanagemôt was continued, but turned into a sort of feudal court in which the officials of the kingdom, the feudal lords, had places. The Witan became continually a smaller body of men, who were joined with those officers of the royal power higher than they. It must be remembered that the Conqueror did not make his claim to the throne because he had won his right by the sword. He always insisted that he was the lawful successor to Eadward, and the name of Harold the Usurper was omitted from the list of English kings. Following this belief or pretence he was always careful to respect the nationality of the country, and made himself as nearly as possible an Englishman. His plans for supplanting the weakness and insularity of many English institutions by certain Continental fashions, wrought a tremendous change, and put the undeveloped and self-centred kingdom that he had won, on a footing with other European powers. The very taxes which were wrung from the unwilling citizens, no doubt, forced them to wider enterprise and the expansion of their powers of resource. Much of England's later growth has sprung from seed that was planted in these years -- this early spring-time of her prosperity, when William's stern hands swept from field and forest the vestiges of earlier harvests, and cleared the garden grounds into leafless deserts, only to make them ready for future crops.

The very lowest classes were more fortunate under William's rule than they had been in earlier times. Their rights and liberties were extended, and they could claim legal defence against the tyrannies of their masters. But the upper ranks of people were much more dissatisfied and unhappy. The spirit of the laws was changed; the language of the court was a foreign language; and the modified feudalism of the king put foreigners in all high places, who could hold the confiscated estates, and laugh at the former masters now made poor and resourceless. The folk-land had become Terra Regis; England was only a part of Normandy, and the king was often away, busier with the affairs of his duchy than of his kingdom. Yet, as had often happened before in this growing nation's lifetime, a sure process of amalgamation was going on, and though the fire of discontent was burning hot, the gold that was England's and the gold that was Normandy's were being melted together and growing into a greater treasure than either had been alone. We can best understand the individuality and vital force of the Norman people by seeing the difference their coming to England has made in the English character. We cannot remind ourselves of this too often. The Norman of the Conqueror's day was already a man of the world. The hindering conditions of English life were localism and lack of unity. We can see almost a tribal aspect in the jealousies of the earldoms, the lack of sympathy or brotherhood between the different quarters of the island. William's earls were only set over single shires, and the growth of independence was rendered impossible; and his greatest benefaction to his new domain was a thoroughly organized system of law. As we linger over the accounts of his reign, harsh and cruel and unlovable as he appears, it is rather the cruelty of the surgeon than of a torturer or of a cut-throat. The presence of the Normans among the nations of the earth must have seemed particularly irritating and inflammatory, but we can understand, now that so many centuries have smoothed away the scars they left, that the stimulus of their energy and their hot ambition helped the rest of the world to take many steps forward.

While we account for the deeds of the fighting Normans, and their later effects, we must not forget their praying brethren who stood side by side with them, lording it over the English lands and reaching out willing hands for part of the spoils. We must thank them for their piety and their scholarship, and for the great churches they founded, even while we laugh at the greed and worldlinesss under their monkish cloaks. Lanfranc was made bishop of Canterbury, and wherever the Conqueror's standard was planted, wherever he gained foothold, as the tide of his military rule ebbed and flowed, he planted churches and monasteries. Especially he watched over his high-towered Battle Abbey, which marked the spot where the banner of the Fighting Man was defeated and the banner of the Three Lions of Normandy was set up in its place.

Before we go further we must follow the king back to his duchy in the spring after that first winter in England. Three Englishmen were chosen to attend his royal highness, and although they might easily guess that there was something more than mere compliment in this flattering invitation, these northern earls, Eadwine, Morkere, and Waltheof (the Bear's great-grandson), were not anxious to hurry forward the open quarrel which William himself was anxious to avoid. Nothing could have been more unsafe in the unsettled condition of England than to have left these unruly leaders to plot and connive during his absence; besides, it would be a good thing to show such rough islanders the splendours of the Norman court.

The Norman chroniclers are not often willing to admit that England was in any respect equal to their own duchy, but when they have to describe William's triumphant return, they forget their prudence and give glowing accounts of the treasure of gold and silver that he brings with him, and even the magnificent embroideries, tapestries and hangings, and clerical vestments, -- though they have so lately tried to impress upon their readers that heathen squalor of social life across the Channel which the Christian had sought to remedy. Church after church was richly endowed with these spoils, and the Conqueror's own Church of St. Stephen at Caen fared best of all. Beside the English wealth we must not forget the goods of Harold Hardrada, which had been brought with such mistaken confidence for the plenishing of his desired kingdom. There is a tradition of a mighty ingot of gold won in his Eastern adventures, so great that twelve strong youths could scarcely carry it. Eadwine and Morkere of Northumberland must have looked at that with regretful eyes.

Whatever the English prejudice might have been, the Normans had every reason to be proud of their seventh duke. He had advanced their fortunes in most amazing fashion, and they were proud of him indeed on the day when he again set his foot on Norman ground. The time of year was Lent. Spring was not yet come, but it might have been a summer festival, if one judged by the way that the people crowded from the farthest boundaries of the country to the towns through which William was to pass. It was like the glorious holidays of the Roman Empire. The grateful peasants fought and pushed for a sight of their leader. The world is never slow to do honor to its great soldiers and conquerors. The duke met his wife at Rouen, and that was the best moment of all; Matilda had ruled Normandy wisely and ably during his five or six months' absence, with old Roger de Beaumont for her chief counsellor.

The royal procession trailed its gorgeous length from church to church and from city to city about the duchy; the spoils of England seemed inexhaustible to the wondering spectators, and those who had made excuse to lag behind when their bows and lances were needed, were ready enough now to clutch their hands greedily in their empty pockets and follow their valiant countrymen. William himself was not slow in letting the value of his new domain be known; the more men the better in that England which might be a slippery prize to hold. He had many a secret conference with Lanfranc, who had been chief adviser and upholder of the invasion. The priest-statesman seems almost a greater man than the soldier-statesman; many a famous deed of that age was Lanfranc's suggestion, but nobody knew better than these two that the conquest of England was hardly more than begun, and long and deep their councils must have been when the noise of shouting in the streets had ended, and the stars were shining above Caen.

No city of Normandy seems more closely connected with those days than Caen. As one walks along its streets, beneath the high church towers and gabled roofs of the houses, it is easy to fancy that more famous elder generation of Normans alive again, to people Caen with knights and priests and minstrels of that earlier day. The Duchess Matilda might be alive yet and busy with her abbey church of Holy Trinity and her favorite household of nuns; the people shout her praises admiringly, and gaze at her lovingly as she passes through the street with her troop of attendants. Caen is prosperous and gay. "Large, strong, full of draperies and all sorts of merchandise; rich citizens, noble dames, damsels, and fine churches," says Froissart years afterwards. Even this very year one is tempted to believe that one sees the same fields and gardens, the same houses, and hears the same bells that William the Conqueror saw and heard in that summer after he had become king of England.

And in Bayeux, too, great portions of the ancient city still remain. There where the Northmen made their chief habitation, or in Rouen or Falaise, we can almost make history come to life. Perhaps the great tapestry was begun that very summer in Bayeux; perhaps the company of English guests, some of those noble dames well-skilled in "English work" of crewel and canvas, were enticed by Bishop Odo into beginning that "document in worsted" which more than any thing else has preserved the true history of the Conquest of England. Odo meant to adorn his new church with it, and to preserve the account of his own part in the great battle and its preliminaries, with the story of Harold's oath and disloyalty, and William's right to the crown. There is an Italian fashion of drawing in it -- the figures are hardly like Englishmen or Normans in the way they stand or make gestures to each other in the rude pictures. Later history has associated the working of these more than fifteen hundred figures with Matilda and her maidens, as a tribute to the Conqueror's valor, but there are many evidences to the contrary. The old idea that the duchess and her women worked at the tapestry, and said their prayers while the army had gone to England, seems improbable the more one studies the work itself. Yet tradition sometimes keeps the grain of truth in its accumulation of chaff. There is no early record of it, and its historical value was rediscovered only in 1724 by a French antiquary. The bright worsteds of it still keep their colors on the twenty-inches wide strip of linen, more than two hundred feet in length. Odo is said to have given it to his chapter at Bayeux, and it has suffered astonishingly little from the ravages of time.

But we must return to Norman affairs in England. Odo himself and William Fitz-Osbern had been made earls of the Counties Palatine of Kent and Hereford, and were put in command in William's absence. The rapacity of these Norman gentlemen was more than their new subjects could bear. The bishop at least is pretty certain to have covered his own greedy injustice by a plea that he was following out the king's orders. Revolt after revolt troubled the peace of England. Harold's two sons were ready to make war from their vantage-ground in Ireland; the Danes and Scots were also conspiring against the new lord of the English. At last some of the Normans themselves were traitorous and troublesome, but William was fully equal to such minor emergencies as these. He went back to England late in 1067, after spending the summer and autumn in Normandy, and soon found himself busy enough in the snarl of revolt and disagreement. One trouble followed another as the winter wore away.[,] The siege of Exeter was the most conspicuous event. But [but] here too William was conqueror, and Southwestern England was forced to submit to his rule. At Easter-tide a stately embassy was sent to bring over the Duchess Matilda from Normandy, and when it returned she was hallowed as Queen by Ealdred the archbishop. Let us hope that, surrounded by her own kindred and people, she did not see the sorrowful English faces of those women who had lost husband and home together, and who had been bereft of all their treasures that strangers might be enriched.

There is a curious tradition that a little while after this, much woe was wrought because those other Norman ladies, whose lords had come over to England to fight and remained to plunder, refused to join them, because they were not fond of the sea, and thought that they were not likely to find better fare and lodging. Very likely the queen's residence in her new possessions had a good effect, but some of the Norman men were obliged to return altogether, their wives having threatened to find new partners if they were left alone any longer. It may have been an excuse or a jest, because so many naturally desired to see their own country again.

Both Saxons and Normans paid great deference to the instinctive opinions of women. When such serious matters as going to war were before them, a woman's unreasoning prejudice or favor of the enterprise was often taken into account. They seem to have almost taken the place of the ancient auguries! However, it is not pleasant to feminine conceit to be told directly that great respect was also paid to the neighing of horses!

Henry, the king's youngest son, was born not long after the queen's arrival, and born too in Northern England the latest and hardest won at that time of the out-lying provinces. The very name that was given to the child shows a desire for some degree of identification with new interests. William and Matilda certainly had England's welfare at heart, for England's welfare was directly or indirectly their own, and this name was a sign of recognition of the hereditary alliance with Germany; with the reigning king and his more famous father. There is nothing more striking than the traditional slander and prejudice which history preserves from age to age. Seen by clearer light, many reported injustices are explained away. If there was in England then, any thing like the present difficulty of influencing public opinion to quick foresight and new decisions, the Conqueror and Baldwin of Flanders' daughter had any thing but an easy path to tread. Selfish they both may have been, and bigoted and even cruel, but they represented a better degree of social refinement and education and enlightenment. Progress was really what the English of that day bewailed and set their faces against, though they did not know it. William and Matilda had to insist upon the putting aside of worn-out opinions, and on coming to England had made the strange discovery that they must either take a long step backward or force their subjects forward. They were not conscious reformers; they were not infallibly wise missionaries of new truth, who tried actually to give these belated souls a wider outlook upon life, but let us stop to recognize the fact that no task is more thankless than his who is trying to go in advance of his time. Men have been burnt and hanged and disgraced and sneered at for no greater crime; in fact, there is nothing that average humanity so much resents as the power to look ahead and to warn others of pitfalls into which ignorant shortsightedness is likely to tumble. Nothing has been so resented and assailed as the thorough survey of England, and the record of its lands and resources in the Domesday Book. Yet nothing was so necessary for any sort of good government and steady oversight of the nation's affairs. We only wonder now that it was not made sooner. The machinery of government was of necessity much ruder then. No doubt William's tyranny swept its course to and fro like some Juggernaut car regardless of its victims, yet for England a unified and concentrated force of government was the one thing to be insisted upon; Harold and his rival earls might have been hindering, ineffectual rulers of the country's divided strength and jealous partisanship.

Yet the future right direction and prosperity of England was poor consolation to the aching hearts of the women of that time, or the landless lords who had to stand by and see new masters of the soil take their places. What was won by William's sword must be held by his sword, and the more sullen and rebellious the English grew, the more heavily they were taxed and the faster the land was rid of them. They were chased into the fens, and pursued with fire and bloodshed. "England was made a great grave," says Dickens, "and men and beasts lay dead together." The immediate result of the Conqueror's rule was like fire and plough and harrow in a piece of new land.

It was a sad and tiresome lifetime, that of the Conqueror; just or unjust toward his new subjects, they hated him bitterly; his far-sighted plans for the country's growth and development gave as much displeasure as the smallest of his personal prejudices or selfish whims. Every man's hand was against him, and hardly an eye but flashed angrily at the sight of the king. Eadward the Confessor, pious ascetic, and relic-worshipper, had loved the chase as well as this warlike successor of his ever loved it, and had been very careful of his royal hunting-grounds, but nobody raised an outcry against his unsaintly love of slaughtering defenceless wild creatures, or thought him the less a meek and gentle soul, beloved by angels and taught by them in visions. But ever since, the Conqueror's love of hunting has been an accusation against him as if he were the only man guilty of it, and his confiscation of the Hampshire lands to make new forest seemed the last stroke that could be borne. The peasants' cottages were swept away and the land laid waste. Norman was master and Englishman was servant. The royal train of horses and dogs and merry huntsmen in gay apparel clattered through the wood, and from hiding-places under the fern men watched them and muttered curses upon their cruel heads. There were already sixty-eight royal forests in different parts of the kingdom before New Forest was begun. Everybody thought that England had never seen such dark days, but so everybody thought when the Angles and Saxons and Jutes came, and even so vigorous a pruning and digging at the roots as this made England grow the better.

Large tracts of the hunting-grounds had been unfit for human habitation, and it was better to leave them to the hares and deer. Wide regions of the country, too, were occupied by the lowest class of humanity, who lived almost in beastly fashion, without chance of enlightenment or uplifting. They were outlaws of the worst sort who could not be brought into decent order or relationship with respectable society, and it was better for these to be chased from their lairs and forced to accept the companionship of townsfolk. With these, however, there were many who suffered undeserved. Among the rank weeds of England there were plucked many blooming things and useful growths of simple, long-established home-life and domestic affection. When fire was leaping high at the city gates it is impossible not to regret its enmity against dear and noble structures of the past, even though it cleared the way for loftier minsters and fairer dwelling-places. In criticising and resenting such a reign as William the Norman's over England, we must avoid a danger of not seeing the hand of God in it, and the evidences of an overruling Providence, which works in and through the works of men and sees the end of things from the beginning as men cannot. There may be overstatement in William of Malmesbury's account of the bad condition of the country at the time of the Conquest, but the outlines of it cannot be far from right. "In process of time," he says, "the desire after literature and religion had decayed for several years before the arrival of the Normans. The clergy, contented with a very slight degree of learning, could scarcely stammer out the words of the sacraments, and a person who understood grammar was an object of wonder and astonishment. The nobility were given up to luxury and wantonness. The commonalty, left unprotected, became a prey to the most powerful, who amassed fortunes by either seizing on their property or selling their persons into foreign countries; although it be an innate quality of this people to be more inclined to revelling than to the accumulation of wealth. Drinking was a universal practice, in which they passed whole nights, as well as days. They consumed their whole substance in mean, despicable houses, unlike Normans and French, who, in noble and splendid mansions, lived with frugality." "There cannot be a doubt," says Mr. Bruce in his interesting book about the Bayeux tapestry, "that by the introduction of the refinements of life the condition of the people was improved, and that a check was given to the grosser sensualities of our nature. Certain it is that learning received a powerful stimulus by the Conquest. At the period of the Norman invasion a great intellectual movement had commenced in the schools on the Continent. Normandy had beyond most other parts profited by it. William brought with him to England some of the most distinguished ornaments of the school of his native duchy; the consequence of this was that England henceforward took a higher walk in literature than she had ever done before." One great step was the freeing of the lower classes; there was one rank of serfs, the churls, who were attached to the land, and were transferred with it, without any power of choosing their employer or taking any steps to improve their condition. Another large class, the thews, were the absolute property of their owners. William's law that every slave who had lived unchallenged a year and a day in any city or walled town in the kingdom should be free forever, was, indeed, "door of hope to many," besides the actual good effects of town life, the natural rivalry and promotion of knowledge, the stimulus given to the cultivation and refinements of social life. He protected the early growth of a public sentiment, which was finally strong enough to venture to assert its rights and to claim recognition. He relentlessly overthrew the flourishing slave-trade of the town of Bristol and no doubt made many enemies by such an act.

Whatever may have been the king's better nature and earlier purposes in regard to his kingdom and duchy, as he grew older one finds his reputation growing steadily worse. He must have found the ruling of men a thankless task, and he apparently cared less and less to soften or control the harshness of his underrulers and officers. His domestic relations had always been a bright spot in his stern, hard life, but at length even his beloved wife Matilda no longer held him first, and grieved him by favoring their troublesome son Robert, who was her darling of all their children. Robert and his mother had been the nominal governors of Normandy when he was still a child and his father was away in England. They seem to have been in league ever afterward, for when Robert grew up he demanded Normandy outright, which made his father angry, and the instant refusal provoked Master Curt-hose to such an extent that he went about from court to court in Europe bewailing the injustice that had been shown him. He was very fond of music and dancing, and spent a great deal of money, which the queen appears to have been always ready to send him. He was gifted with a power of making people fond of him, though he was not good for very much else.

After a while William discovered that there was a secret messenger who carried forbidden supplies to the rebellious prince, and the messenger happily had time to betake himself to a convenient convent and put on the dress and give, let us hope, heart-felt vows of monkhood. This is what Orderic Vitalis reports of a meeting between the king and queen: "Who in the world," sighs the king, "can expect to find a faithful and devoted wife? The woman whom I loved in my soul, and to whom I entrusted my kingdom and my treasures, supports my enemies; she enriches them with my property; she secretly arms them against my honor -- perhaps my life." And Matilda answered: "Do not be surprised, I pray you, because I love my eldest born. Were Robert dead and seven feet below the sod, and my blood could raise him to life, it should surely flow. How can I take pleasure in luxury when my son is in want? Far from my heart be such hardness! Your power cannot deaden the love of a mother's heart." The king did not punish the queen, we are assured gravely; and Robert quarrelled with his brothers, and defied his father, and won his mother's sympathy and forbearance to the end. He found the king of France ready to uphold his cause by reason of the old jealousy of William's power, and while he was ensconced in the castle of Gerberoi, and sallying out at his convenience to harry the country, William marched to attack him, and the father and son fought hand to hand without knowing each other until the king was thrown from his horse. Whereupon Robert professed great contrition, and some time afterward, the barons having interceded and Matilda having prayed and wept, William consented to a reconciliation, and even made his son his lieutenant over Normandy and Brittany.

In 1083 the queen died, and there was nobody to lift a voice against her prudence and rare virtue, or her simple piety. There was no better woman in any convent cell of Normandy, than the woman who had borne the heavy weight of the Norman crown, and who had finished the sorry task as best she could, of reigning over an alien, conquered people. The king's sorrow was piteous to behold, and not long afterward their second son, Richard, was killed in the New Forest, a place of misfortune to the royal household. Another trouble quickly followed, which not only hurt the king's feelings, but made him desperately angry.

William had been very kind to all his kinsfolk on his mother's side, and especially to his half-brother, Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux. He had loaded him with honors, and given him, long ago, vice-regal authority in England. Even this was not enough for such an aspiring ecclesiastic, and, under the pretence of gathering tax-money (no doubt insisting that it was to serve the miserliness and greed of the king), he carried on a flourishing system of plundering. After a while it was discovered that he had an ambition to make himself Pope of Rome, and was using his money for bribing cardinals and ingratiating himself with the Italian nobles. He bought himself a palace in Rome and furnished it magnificently, and began to fit out a fleet of treasure-ships at the Isle of Wight. One day when they were nearly ready to set sail, and the disloyal gentlemen who were also bound on this adventure were collected into a comfortable group on shore, who should appear among them but William himself. The king sternly related what must have been a familiar series of circumstances to his audience: Odo's disloyalty when he had been entirely trusted, his oppression of England, his despoiling of the churches and the confiscation of their lands and treasures, lastly that he had even won away these knights to go to Rome with him; men who were sworn to repulse the enemies of the kingdom.

After Odo's sins were related in detail, he was seized, but loudly lamented thereat, declaring that he was a clerk and a minister of the Most High, and that no bishop could be condemned without the judgment of the Pope. The people who stood by murmured anxiously, for nobody knew what might be going to happen to them also. Crafty William answered that he was seizing neither clerk, nor prelate, nor Bishop of Bayeux, only his Earl of Kent, his temporal lieutenant, who must account to him for such bad vice-regal administration, and for four years after that Odo was obliged to content himself with close imprisonment in the old tower of Rouen.

Those four years were in fact all that remained of the Conqueror's earthly lifetime, and dreary years they were. In 1087 William returned to Normandy for the last time. The French king was making trouble; some say that the quarrel began between the younger members of the family, others that Philip demanded that William should do homage for England. Ordericus Vitalis, the most truthful of the Norman historians, declares that the dispute was about the proprietorship of the French districts of the Vexin.

The Conqueror was an old man now, older than his years; he had never quite recovered from his fall when Robert unhorsed him at the castle of Gerberoi; besides he had suffered from other illness, and had grown very stout, and the doctors at Rouen were taking him in charge. The king of France joked insolently about his illness, and at the end of July William started furiously on his last campaign, and no doubt took vast pleasure in burning the city of Mantes. When the fire was down he rode through the conquered town, his horse stepped among some smouldering firebrands and reared, throwing his clumsy rider suddenly forward against the high pommel of the saddle, a death-blow from which he was never to recover. He was carried back to Rouen a worse case for the doctors' skill than ever, and presently fever set in, and torture followed torture for six long weeks. The burning fever, the midsummer heat, the flattery or neglect of his paid attendants; how they all reminded him and made him confess at last his new understanding and sorrow for the misery he had caused to many another human being! Yet we can but listen forgivingly as he says: "At the time my father went of his own will into exile, leaving to me the Duchy of Normandy, I was a mere child of eight years, and from that day to this I have always borne the weight of arms."

The three sons, Rufus William, Robert Curt-hose, and Henry Beauclerc, were all eager to claim their inheritance, but the king sends for Anselm, the holy abbot, and puts them aside while he makes confession of his sins and bravely meets the prospect of speedy death. He gives directions concerning the affairs of England and Normandy, gives money and treasure to poor people and the churches; he even says that he wishes to rebuild the churches which were so lately burnt at Mantes. Then he summons his sons to his bedside and directs those barons and knights who were present to be seated, when, if we may believe Ordericus the Chronicler, the Conqueror made an eloquent address, reviewing his life and achievements and the career of many of his companions. The chronicle writers had a habit of putting extremely pious and proper long speeches into the mouths of dying kings, and as we read these remarks in particular we cannot help a suspicion that the old monk sat down in his cell some time afterward and quietly composed a systematic summary of what William would have said, or ought to have said if he could. Yet we may believe in the truth of many sentences. We do not care for what he expressed concerning Mauger or King Henry, the battle of Mortemer or Val-ès-dunes, but when he speaks of his loyalty to the Church and his friendship with Lanfranc, and Gerbert, and Anselm, of his having built seventeen monasteries and six nunneries, "spiritual fortresses in which mortals learn to combat the demons and lusts of the flesh"; when he tells his sons to attach themselves to men of worth and wisdom and to follow their advice, to follow justice in all things and spare no effort to avoid wickedness, to assist the poor, infirm, and honest, to curb and punish the proud and selfish, to prevent them from injuring their neighbors, devoutly to attend holy church, to prefer the worship of God to worldly wealth; -- when he says these things we listen, and believe that he was truly sorry at last for the starving homeless Englishmen who owed him their death, for even the bitter resentment he showed for the slaughter of a thousand of his brave knights within the walls of Durham. He dares not give the ill-gotten kingdom of England to anybody save to God, but if it be God's will he hopes that William Rufus may be his successor. Robert may rule Normandy. Henry may take five thousand pounds' weight of silver from the treasury. It is true that he has no land to dwell in, but let him rest in patience and be willing that his brothers should precede him. By and by he will be heir of everything.

At last the king unwillingly gives permission for Odo's release along with other prisoners of state. He prophesies that Odo will again disturb the peace and cause the death of thousands, and adds that the bishop does not conduct himself with that chastity and modesty which become a minister of God. For a last act of clemency he gives back to Baudri, the son of Nicolas, all his lands, "because without permission he quitted my service and passed over into Spain. I now restore them to him for the love of God; I do not believe that there is a better knight under arms than he, but he is changeable and prodigal, and fond of roving into foreign countries."

On the morning of the eighth of September the great soul took its flight. The king was lying in restless, half-breathless sleep or stupor when the cathedral bells began to ring, and he opened his eyes and asked what time it was. They told him it was the hour of prime. "Then he called upon God as far as his strength sufficed, and on our holy lady, the blessed Mary, and so departed while yet speaking, without any loss of his senses or change of speech."

"At the time when the king departed this world, many of his servants were to be seen running up and down, some going in, others coming out, carrying off the rich hangings and the tapestry, and whatever they could lay their hands upon. A whole day passed before the corpse was laid upon its bier, for they who were wont before to fear him now left him lying alone. But when the news spread much people gathered together, and bishops and barons came in long procession. The body was well tended and carried to Caen as he had before commanded. There was no bishop in the province, nor abbot, nor noble prince, who did not go to the burying if he could, and there were besides many monks, priests, and clerks."

So writes Master Wace in his long rhyme of the Conquest; but the rhyme does not end as befits the Conqueror's fame. The chanting monks had hardly set the body down within the church, at the end of its last journey, when there was a cry of fire without, and all the people ran away and left the church empty save for the few monks who stayed beside the bier. When the crowd returned the service went on again, but just as the grave was ready a vavasour named Ascelin, the son of Arthur, pushed his way among the bishops and barons, and mounted a stone to make himself the better heard -- "Listen to me, ye lords and clerks!" he cries; "ye shall not bury William in this spot. This church of St. Stephen is built on land that he seized from me and my house. By force he took it from me, and I claim judgment. I appeal to him by name that he do me right."

"After he had said this he came down. Forthwith arose great clamor in the church, and there was such tumult that no one could hear the other speak. Some went, others came; and all marvelled that this great king, who had conquered so much and won so many cities and so many castles, could not call so much land his own as his body might be covered in after death."

We cannot do better than end with reading the Saxon chronicle, which is less likely to be flattering than the Norman records.

"Alas, how false and unresting is this earth's weal! He that erst was a rich king, and lord of many lands; had then of all his lands but seven feet space; and he that was once clad with gold and gems, lay overspread with mold! If any one wish to know what manner of man he was, or what worship he had, or of how many lands he was the lord, then will we write of him as we have known him; for we looked on him and somewhile dwelt in his herd.

"This King William that we speak about was a very wise man and very rich; more worshipped, and stronger than any of his foregangers were. He was mild to the good men that loved God, and beyond all metes stark to those who withsaid his will. On that same ground where God gave him that he should win England, he reared a noble minster and set monks there and well endowed it.

"Eke he was very worshipful. Thrice he wore his king-helm (crown), every year as oft as he was in England. At Easter he wore it at Winchester; at Pentecost at Westminster; at midwinter at Gloucester, and then were with him all the rich men over all England: archbishops and diocesan bishops; abbots and earls; thanes and knights. Truly he was so stark a man and wroth that no man durst do any thing against his will. He had earls in his bonds who had done against his will. Bishops he set off their bishoprics, and abbots off their abbacies, and thanes in prison. And at last he did not spare his brother Odo; him he set in prison. Betwixt other things we must not forget the good peace that he made in this land, so that a man that was worth aught might travel over the kingdom unhurt with his bosom full of gold. And no man durst slay another man though he had suffered never so mickle evil from the other.

"He ruled over England, and by his cunning he had so thoroughly surveyed it, that there was never a hide of land in England that he wist not both who had it and what its worth was, and he set it down in his writ. Wales was under his weald, and therein he wrought castles; and he wielded Manncynn withal. Scotland he subdued by his mickle strength. Normandy was his by kin -- and over the earldom that is called Mans he ruled. And if he might have lived yet two years he had won Ireland, and without any armament.

"Truly in his time men had mickle taxing and many hardships. He let castles be built, and poor men were sorely taxed. The king" (we might in justice read oftener the king's officers) -- "The king was so very stark, and he took from his subjects many marks of gold and many hundred pounds of silver, and that he took of his people some by right and some by mickle unright, for little need. He was fallen into covetousness, and greediness he loved withal.

"The king and the head men loved much, and over much, the getting in of gold and silver, and recked not how sinfully it was got so it but came to them. . . .

"He set many deer-friths and he made laws therewith, that whosoever should slay hart or hind, him man should blind. And as he kept to himself the slaying of the harts, so eke did he the boars. He loved the high deer as much as if he were their father. Eke he set as to the hares that they should go free. His rich men bemoaned, and his poor men murmured, but he recked not the hatred of them all, and they must follow the king's will if they would have lands or goods or his favor.

"Wa-la-wa! that any man should be so moody, so to upheave himself and think himself above all other men! May God Almighty have mild-heartedness on his soul and give him forgiveness of his sins! These things we have written of him both good and evil, that men may choose the good after their goodness, and withal flee from evil, and go on the way that leadeth all to heaven's kingdom."

Notes for Chapter 16

across the fateful seas: From "Helena" in Under the Olive (1881), by Annie Fields.

[ Back ]

good-will to men: See Luke 2:14 in the King James version familiar to Jewett. The sentence was repeated in familiar Christmas carols, including the refrain in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Christmas hymn, "I heard the bells on Christmas Day" (1867).

I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

[ Back ]

the churls: medieval English peasants.

[ Back ]

ingot of gold; The tradition of Harold Handrada's ingot of gold is reported in Freeman, Vol. 4, p. 55-6. Freeman also points out the ways in which superior English artisans were valued by William and the Normans. (Jewett's Sources). The quotation from William of Malmesbury's account:

[ Back ]

Froissart: French historian of 11th-century England & Normandy. This quotation from his work appears at the beginning of Chapter 4 of Normandy Picturesque (1870) by Henry Blackburn.

Wikipedia says: "Jean Froissart (c. 1337 – c. 1405), … was a medieval French chronicle writer. For centuries, Froissart's Chronicles have been recognized as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th century Kingdom of England and France. His history is also an important source for the first half of the Hundred Years' War.

This quotation is from The Chronicles, and it appeared in other contemporary sources, but it is not clear which translation Jewett may have used. The original is:

Quant le roy d’Engleterre et ses gens eurent fait leur voulenté de la ville de Saint Leu en Constantin, ilz s’en partirent et prindrent leur chemin pour venir encore pardevers plus grosse ville III fois appellee Caen, plaine de tresgrant richesce de drapperie et de toutes marchandises, de riches bourgois, de nobles dames, de moult belles eglises …An English translation of the passage appears in The Ancient Chronicles of Sir John Froissart, of England, France, Spain, Portugal, Scotland, Brittany, and Flanders, and the Adjoining Countries, Volume 1 (1914) p. 273, but this does not appear to be Jewett's source.

[ Back ]

Bayeux tapestry: See Wikipedia:

To see images of the tapestry, click here.

Wikipedia confirms Jewett's speculation about its origins. Jewett may draw upon J. C. Bruce, pp. 1-3, but more likely she responds to the detailed examination of studies of the origin of the tapestry in Freeman, v. 3, pp. 375-85. (Jewett's Sources).

[ Back ]

Domesday Book: A survey commissioned by William I and completed in 1088, to determine English resources and property with some precision, for the purpose of taxation.

[ Back ]

a great grave: This quotation, though not exact, is from Charles Dickens, A Child's History of England (1851-54), Chapter VIII.

"King William, fearing he might lose his conquest, came back, and tried to pacify the London people by soft words. He then set forth to repress the country people by stern deeds. Among the towns which he besieged, and where he killed and maimed the inhabitants without any distinction, sparing none, young or old, armed or unarmed, were Oxford, Warwick, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Lincoln, York. In all these places, and in many others, fire and sword worked their utmost horrors, and made the land dreadful to behold. The streams and rivers were discoloured with blood; the sky was blackened with smoke; the fields were wastes of ashes; the waysides were heaped up with dead. Such are the fatal results of conquest and ambition! Although William was a harsh and angry man, I do not suppose that he deliberately meant to work this shocking ruin, when he invaded England. But what he had got by the strong hand, he could only keep by the strong hand, and in so doing he made England a great grave.

… In melancholy songs, and doleful stories, it was still sung and told by cottage fires on winter evenings, a hundred years afterwards, how, in those dreadful days of the Normans, there was not, from the River Humber to the River Tyne, one inhabited village left, nor one cultivated field—how there was nothing but a dismal ruin, where the human creatures and the beasts lay dead together."

[ Back ]

lived with frugality: See The Library of Original Sources: Volume IV (Early Mediaeval Age) 2004, compiled by Oliver J. Thatcher, for William of Malmesbury's "Saxons and Normans." This quotation appears on p. 387. Jewett's source, however, is almost certainly J. C. Bruce, as shown in the note on him below.

William of Malmesbury (c. 1095/96 - c. 1143) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century, according to Wikipedia:

[ Back ]

deference to the instinctive opinions of women: Richard Cary in Sarah Orne Jewett (1962, p. 157) attributes this "disputable statement" to Jewett's "feminist bias." While it is true that Jewett makes a visible effort to attend to the roles specific women and women in general played in the history of the Normans, it is not clear that she goes beyond her sources in doing so. For one example, Richard Palgrave devotes a long paragraph of his detailed history (v. 2, pp. 777-8) to the influence of specific women, such as Joan of Arc and Pompadour upon the history of France. Keyser, in The Private Life of the old Northmen (1868) also noted that women had a highly respectable position in society (p 17). See also Kingsley's Hereward (1865) where Hereward's wife and mother, among others, are shown to be powerful in influencing male leaders, notably in decisions about engaging in war.

(Jewett's Sources).

[ Back ]

Mr. Bruce ... interesting book about the Bayeux tapestry: The Bayeux Tapestry Elucidated, (1856), by John Collingwood Bruce. Jewett borrows liberally from Bruce, not simply the two passages she quotes – with slight alterations (pp. 158-159). The later quotation also is from Bruce, "a door of hope to many" (p. 160).

The Malmesbury quotation is given here in part, and it also is cited in a note in volume 1 of Bulwer-Lytton's Harold, another of Jewett's sources (p. 218).

[ Back ]

Orderic Vitalis: Ordericus Vitalis (1075 - c.1142) was an English born monk who worked at Saint Evroult in Normandy. His great work is Historia ecclesiastica which is "one of the fullest and most graphic accounts of Anglo Norman society in his own day." Jewett offers two spellings of his name in this chapter.

His Ecclesiastical History is available as a Google Book in a translation to which Jewett may have had access.

Volume 1

Volume 2:

However, the passage she quotes, which appears in v. 2, p. 174, shows that she is not quoting from the Thomas Forester translation:

An apparently different translation of the quotation appears in Jonathan Duncan, The Dukes of Normandy, from the times of Rolls to the expulsion of king John (1839), p. 122.

Jewett's actual source, however, remains unknown.

[ Back ]

most truthful of the Norman historians: Jewett seems again to quote and borrow from Duncan, pp. 126-7. (See above).

[ Back ]

always borne the weight of arms: This quotation approximates the account drawn from Vitalis in Duncan, pp. 127-8. Neither is Jewett's text here the same as in Forester's translation of Orderic, v. 2, p. 408. Jewett's actual source remains unknown. (See above).

[ Back ]

the demons and lusts of the flesh: See Duncan, p. 134, though Jewett does not quote exactly. (See above).

prodigal, and fond: Duncan, p. 140. (See above).

[ Back ]

hour of prime: the first hour of daylight in the liturgical day, when first prayers are said. A note in Taylor's translation of Master Wace gives the time as 6 a.m.

[ Back ]

Then he called upon God: This and the following quotations are from Taylor's translation of Master Wace, p. 279.

Master Wace his chronicle of the Norman conquest from the Roman de Rou. Tr. with notes and illus. by E. Taylor, 1837.

[ Back ]

vavasour: Wikipedia says vavasour is "a term in Feudal law. A vavasour was the vassal or tenant of a baron, one who held their tenancy under a baron, and who also had tenants under him." Master Wace recounts this episode in greater detail, 280-81. Likewise, the incident described in Freeman, v. 4, pp. 487-8, varies from Jewett's account. See also Palgrave, vol. 3, pp. 583-90, though Jewett does not seem to draw directly upon this account. Her actual source for quotations remains unknown. (Jewett's Sources).

[ Back ]

the Saxon chronicle… "Alas, how false and unresting … all to heaven's kingdom": This passage from Wace's conclusion is in Thorpe's translation, volume 2, pp. 189-90, though not as Jewett quotes it. The translation I have located on-line that comes closest to Jewett is Taylor's (1837), pp. 283-7. (Jewett's Sources).

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College, with assistance from Allison Anderson and Gabe Heller.

.

| Return to The Normans |