Main Contents & Search

A Native of Winby

Jim's Little Woman

.

The Diverse People of "Jim's Little Woman" by Sarah Orne Jewett

"I didn't know there was such a place as this in America! "

Jewett's "Jim's Little Woman" is characterized in part by the diversity of its characters. The main characters, Marty and Jim, represent ethnic mixing within themselves and in their marriage. This diversity makes up a part of the diversity Jewett depicts in the city in which the story is set, St. Augustine, Florida in about 1890.

Marty's leading physical characteristics are her smallness, pale skin, and red hair. These contrast with Jim's great size and his dark complexion. By temperament each experiences an internal conflict. For Jewett's 19th-century readers, Marty's red hair and short temper would suggest a Scots-Irish ancestry. She regrets her temper, and she draws in part upon her restrained New England cultural background to bring it under control. Jim traces his ancestry to a Yankee grandfather and a Minorcan grandmother. He comes to regret what he sees as his dark Spanish moods and undertakes greater self-control.

Jim and Marty's union is a mixed marriage by the standards of the Gilded Age. Jim is a Catholic, Hispanic-Catalan southerner with New England ancestry, while Marty is a Scots-Irish, Maine Yankee. Probably she is a Protestant, though this is not certain, as she seems rather easily to adapt to Jim's Catholicism once she is in St. Augustine. They work through their troubled marriage within a diverse community that ultimately proves supportive, perhaps in part because the St. Augustine depicted in the story is reasonably successful at integrating its own ethnic diversity.

The main purposes of this presentation are to document the peoples of St. Augustine as they are represented in this story and to explore Marty's and Jim's mixed identities and marriage.

Paula Blanchard. Sarah Orne Jewett. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1994.

Beth Rogero Bowen. St. Augustine in the Gilded Age. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Robert Cassanello. “Avoiding ‘Jim Crow’: Negotiating Separate but Equal on Florida’s Railroads and Streetcars and the Progressive Era Origins of the Modern Civil Rights Movement. ” Journal of Urban History 34 (March 2008), 435-457.

David R. Colburn. Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877-1980. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1991. Colburn’s study was originally published in 1985 and reprinted in 1991.

Thomas Graham. Mr. Flagler's St. Augustine. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014.

James G. Smith. "Before King Came: The Foundations of Civil Rights Movement Resistance and St. Augustine, Florida, 1900-1960"

(2014). UNF Theses and Dissertations. Paper 504.

George Tindall. South Carolina Negroes: 1877-1900. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1952.

Stewart Tolney and E. M. Beck. A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Late 19th-Century St. Augustine Demographics

David R. Colburn in Chapter 2 of Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877-1980, identifies the main demographic groups in St. Augustine at the end of the 19th century.

The old English population

Members of this group tended to focus their energies on cultural and artistic leadership, more than on political and economic leadership, though some were active in local government. They were mainly Protestant and Episcopal. During the tourist season, their numbers were swelled by many of the hotel patrons, who shared their backgrounds and their interests and who interacted with them. Colburn believes that their relationships with hotel patrons tended to accentuate their sense of themselves as a separate group.

The Political Leadership

Though this group included prominent members of the wealthier old English population, those who served in various ways in local governance were mainly the business and economic leaders of the city. Colburn describes this group as insular, close-knit, well-known to each other, conservative, paternalistic, anxious to protect business interests, especially in tourism, and to maintain at least the appearance and, insofar as possible, the reality of a pleasant physical and social atmosphere.

Minorcans

These descendants of a large group of Catalan immigrants to Florida maintained their ethnic distinctness into the 20th century, held together for a long time by continuing to use their language. Jewett implies in the story that Jim and other Minorcan descendents still speak Catalan more than a century after their arrival in 1769. But even as their language became English, Minorcans remained united by their Catholicism. Minorcans were divided by class, some being successful merchants who participated in political and business leadership, but most being working class, such as farmers and fishermen. The latter group was not especially active in community leadership.

African Americans

These made up a large portion of the population, and this swelled considerably during the tourist season, when many Black seasonal workers came to the hotels to serve as waiters, bell-boys, maids, and kitchen help. Economically, local Blacks were at the bottom of the working class, primarily servants and day-laborers.

During the 1887-1896 decade opportunities for Blacks in St. Augustine were superior to many parts of the nation. There was ample work for menial laborers, and wages were better than average. Flagler's hotels helped to provide opportunities for Blacks to advance in limited careers, so that a number of highly successful Blacks could contribute their examples and their wealth to the community. Colburn notes that Lincolnville, a largely but not wholly African American section in the southern part of the old city, provided a pleasant and fairly prosperous community, with a vibrant social and religious life. Still, to the west of the city was a more typically impoverished Black community, home to farm and day-laborers.

Jewett does not portray all of these groups in "Jim's Little Woman." Hotel guests and perhaps some employees appear, as do Minorcans and African Americans. In addition, Jewett also shows smaller groups, such as the Irish and French Catholics.

Cosmopolitan St. Augustine

The old city of St. Augustine had never been more picturesque and full of color than it was that morning. Its narrow thoroughfares, with the wide, overhanging upper balconies that shaded them, were busy and gay. Strangers strolled along, stopping in groups before the open fronts of the fruit shops, or were detained by eager venders of flowers and orange-wood walking-sticks. There were shining shop windows full of photographs and trinkets of pink shell-work and palmetto. There were pink feather fans, and birds in cages, and strange shapes and colors of flowers and fruits, and stuffed alligators. The narrow street was full of laughter and the sound of voices.

The wind-tattered bananas, like wrecked windmills, were putting out fresh green leaves among their ragged ones. There were roses and oranges in bloom, and the country carts were bringing in new vegetables from beyond the old city gates; green lettuces and baskets of pease and strawberries, and trails of golden jasmine were everywhere about the gray town.

These passages depict the crowds and commercial activity that Marty finds a particularly exciting aspect of her new life in St. Augustine, presumably because they contrast with her former life in eastern Maine. When Jim meets Marty, she is working in a lobster-canning establishment in the Booth Bay region, with 12-15 other people in the building. Marty's experience of Maine seems rural and fairly limited in the number and variety of people with whom she associates.

"Jim's Little Woman" takes place

over about two years, approximately in 1888-1890.

In these years, St. Augustine, especially during the

period of January through April, presents Marty with a

cosmopolitan scene. A main feature of the above

passages is the mixture of classes and, implicitly, of

ethnicities. The first passage emphasizes northern

tourists, residents of the several large resort hotels

adjacent to the old city, who stroll and interact with

local vendors in the narrow streets, with their exotic

architecture that reflects the city's history of

alternate Spanish and English occupation before Florida

became United States territory in 1821. Though

these winter visitors came from all over the world, they

were mainly wealthy Americans from major northern cities

such as Chicago, Philadelphia and New York. This

meant that most were Protestant and white.

The vendors were a more mixed

group. While the shop owners included outsiders

attracted to the growing commercial opportunities in a

rapidly developing tourist center, most were local and

would have included descendents of older settlers,

Minorcan, Spanish, and English. The wares also are

partly local, but include products from the more

southern parts of Florida and, especially, from the

Bahamas. Jim's ship, the Dawn of Day, which is in

the harbor in the first passage, trades from the Bahamas

and along the eastern United States coast from St.

Augustine to Mount Desert.

Another group of vendors appears in

the second passage, the local small-acreage farmers who

provide fruits, vegetables and flowers for the open

markets. The rapid growth in the hotels with their

large seasonal staffs and the swelling of the population

during the first four months of each year put pressure

on local growers, such that Henry Flagler had difficulty

supplying his hotels with fresh fruits and vegetables

and eventually established his own local farms for this

purpose (Graham 2014, Chapter 14). These farmers

included descendants of American and Scots-Irish pioneer

settlers, who came to this part of Florida after the

Civil War.

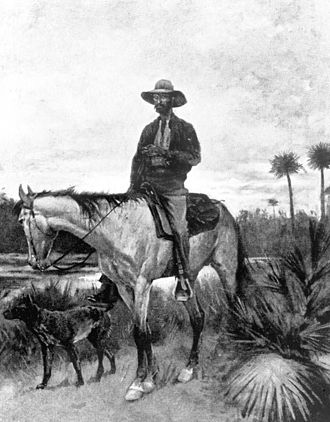

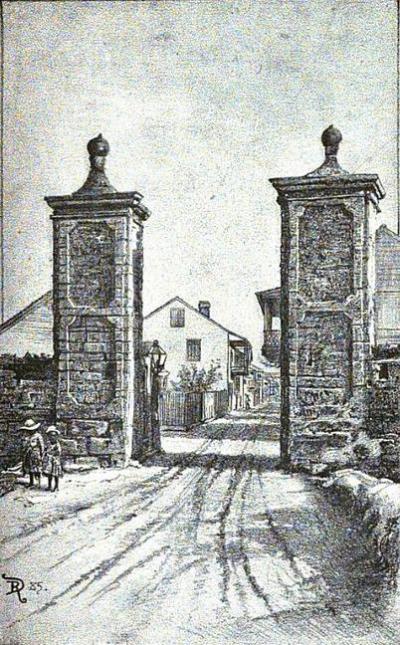

An 1895 drawing

by Frederick Remington of a Florida Cracker.

From Wikipedia.

This passage brings into the portrait of the city the mention of another group of rural locals who appear on the streets. Marsh Tackeys are a breed of horse that Jewett fancifully associates with similar horses that span Europe from Scandinavia to Greece, generally small and agile horses useful in herding. It is likely that Jewett refers to what in the 21st century would be called the Florida Cracker Horse, about which Wikipedia says, "The Florida Cracker Horse is a breed of horse from Florida in the United States. It is genetically and physically similar to many other Spanish-style horses, especially those from the Spanish Colonial Horse group. The Florida Cracker is a gaited breed known for its agility and speed. The Spanish first brought horses to Florida with their expeditions in the early 1500s; as colonial settlement progressed, they used the horses for herding cattle. These horses developed into the Florida Cracker type seen today, and continued to be used by Florida cowboys (known as "crackers") until the 1930s."Lumbering carriages clattered along the palmetto pavement, and boys and men rode by on quick, wild little horses as if for dear life, and to the frequent peril of persons on foot. Sometimes these small dun or cream-colored marsh tackeys needed only a cropped mane to prove their suspected descent from the little steeds of the Northmen, or their cousinship to those of the Greek friezes; they were, indeed, a part of the picturesqueness of the city.

The wild horses that imperil both riders and pedestrians, then, were likely ridden by Florida cowboys. In the late 19th-century, the term "cracker" referred to people of Scots-Irish and English descent who settled in Florida after 1763, when Florida temporarily was under British rule, a number of whom took up the raising of cattle in the wilder landscapes of northern Florida.

There at the pier were the tall masts and the black and green hull of the Dawn of Day. She had come in that morning. ... Her hat blew off and she caught it with one hand, but did not stop to put it on again. The long pier was black with people down at the end next the schooner, and they were swarming up over the side and from the deck. There were red and white parasols from the hotel in the middle of the crowd, and a general hurry and excitement.... Now she could see the pretty Jamaica baskets heaped on the top of the cabin, and the shining colors of shells, and green plumes of sprouted cocoanuts for planting, and the great white branches and heads of coral; she could smell the ripe fruit in the hold, and catch sight of some of the crew.

When the Dawn of Day unloads in the

harbor on the day Marty learns the crew believes Jim has

died in Jamaica, the whole town seems to have gathered

to witness her bereavement. She first notices the ship's

presence when: "Suddenly she became aware that all the

little black boys were running through the streets like

ants, with single bananas, or limp, over-ripe bunches of

a dozen...." This implies that the fruit not fit

for selling is given away to Black children, who likely

meet such ships customarily to solicit free food and

carry some of it home to their families. The

people swarming around the ship seem to include as well

the sailors, workers, merchants who buy parts of the

cargo, and the curious, those female hotel guests whose

red and white parasols appear in the throng.

Such socially, economically, and

racially diverse gatherings were not unusual at this

time in St. Augustine's history. Though the crowd

at the dock in this scene is more or less spontaneous,

in Mr. Flagler's St. Augustine, Thomas Graham

recounts a number of more formally organized events that

included virtually everyone. Among these were

several "grand openings" between 1888 and 1890,

for the Ponce de Leon hotel and the Alacazar hotel

and casino (144-6) and public receptions, such as the

one for President Grover Cleveland in 1888

(164-7). Though racial segregation was generally

the norm, still African Americans attended these events

and mixed with whites in a number of other ways,

including at baseball games (253, 268-9).

While Jewett may not have been fully aware

of the backgrounds of the people who appear in these

scenes, still she shows Marty experiencing and taking

pleasure in the ethnic, racial and class diversity of

the people who fill the streets of St. Augustine during

its busiest season. And in scenes such as at the

dock, Jewett shows this mixture of peoples in an

apparently easy and peaceful interaction that was not

unusual at that time.

All the townsfolk who lived by the water-side and up and down the lanes, and many of the strangers at the hotels, heard of poor Marty's trouble. Her poorest neighbors were the first to send a little purse that they had spared out of their small savings and earnings; then by and by some of the hotel people and those who were well to do in the town made her presents of money and of clothes for the children; and even the spying neighbor of the balcony brought a cake, and some figs, all she had on her tree, the night the news was known, and put them on the table, and was going away without a word, but Marty ran after her and kissed her, for the poor soul's husband had been lost at sea, and so they could weep together.Though the city seems diverse ethnically, economically and socially, still it is a small town in Jewett's portrait. When Marty is in distress, the news gradually spreads through the town, from her near neighbors as far even as to strangers who are hotel employees and guests. Since her poorest neighbors are likely to include Minorcans and African Americans, the families of sailors and laborers, Marty's charitable helpers presumably represent all of the ethnicities of St. Augustine.

One may wonder whether this is a case of Jewett romanticizing St. Augustine by imagining it to be like her own smaller Maine town of South Berwick. Is there evidence that the people of St. Augustine would neighbor a recently arrived outsider more kindly than the citizens of Dunnet Landing care for Mrs. Captain Tolland in Jewett's later story, "The Foreigner" (1900)?

While an incident similar to Marty's supposed widowhood in St. Augustine that Jewett might have known about has not yet been discovered, one may infer positive ideas about the city's communal spirit by reviewing responses to Native American prisoners at Fort Marion during 1875-1887. Wikipedia offers this account:

Beginning in 1875, numerous Native American prisoners were held at the fort in the aftermath of the Indian Wars in the west. Many would die at the fort. Among the captives were Chief White Horse of the Kiowa, and Chief Grey Beard of the Southern Cheyenne.See also:

During this period, Richard Henry Pratt, a Civil War veteran, supervised the prisoners and upgraded the conditions for them. He removed the prisoners' shackles and allowed them out of the casemates where they had been confined. He developed ways to give the men more autonomy and attempted to organize educational and cultural programs for them. They became a center of interest to northerners vacationing in St. Augustine, who included teachers and missionaries. Pratt recruited volunteers to teach the Indian prisoners English, the Christian religion, and elements of American culture. He and most US officials believed that such assimilation was needed for the Indians' survival in the changing society.

The men were also encouraged to make art; they created hundreds of drawings. Some of the collection of Ledger Art by Fort Marion artists is held by the Smithsonian Institution. It may be viewed online.

Encouraged by the men's progress in education, citizens raised funds to send nearly 20 of the prisoners to college after they were released from Ft. Marion. Seventeen men went to the Hampton Institute, a historically black college. Others were sponsored and educated in New York state at private colleges. Among the latter were David Pendleton Oakerhater, as he became known, who was sponsored by US Senator Pendleton (Ohio) and his wife. He studied and later was ordained as an Episcopal priest. He returned to the West to work as a missionary with Indian tribes. He was later recognized by the Episcopal Church as a saint.

Based on his experience at Fort Marion, Pratt recommended wider education of Indian children, a cause which Senator Pendleton embraced. He sponsored a bill supporting this goal, and the US Army offered the Carlisle Barracks in central Pennsylvania as the site of the first Indian boarding school. Its programs were developed along the industrial school model of Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes, which officials thought appropriate to prepare Native Americans for what was generally rural reservation life. Through the early 20th century, the government founded 26 other Indian boarding schools, and permitted more than 450 boarding schools run by religious organizations.

From 1886-1887, approximately 491 Apaches were held prisoner at Fort Marion; many were of the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache bands from Arizona. There were 82 men and the rest were women and children. Among the men, 14, including Chatto, had previously been paid scouts for the US Army. Among the Chiricahua were members of the notable chief Geronimo's band, including his wife. Geronimo was sent to Fort Pickens, in violation of his agreed terms of surrender. While at the fort, many of the prisoners had to camp in tents, as there was not sufficient space for them. At least 24 Apaches died as prisoners and were buried in North Beach.

The Apache Prisoners in Fort Marion (1887) by Herbert Welsh, pp. 12-16.

While the town's charitable actions toward Native Americans are problematic in some ways, it seems clear that there were elements in the community leadership who would provide help to unfortunate strangers.

Jim's grandfather was a Northern man by birth, a New-Englander, who had married a Minorcan woman, and settled down in St. Augustine to spend the rest of his days.Jim's Minorcan ancestry connects him with the history of St. Augustine. Jewett signals the persistence of Minorcan influence by noting that Jim and other Minorcans still sometimes speak a "strange lingo, " which, presumably, would be the Catalan of Minorca.

Go into St. George Street when she would, the narrow thoroughfare was filled with people, and dark-eyed men and women leaned from the balconies and talked to passers-by in a strange lingo which Jim seemed to know.

by Gustave Doré

C. B. Reynolds, p. 19.

The The Standard Guide, St. Augustine (1890 edition) by Charles Bingham Reynolds provides this account of Minorcan immigrants in St. Augustine:

A portion of the population, distinguished by dark eyes and dark complexions is composed of the Minorcans, but they are now an inconspicuous part of the winter throngs. They have given place to the multitudes from abroad; as their ancient coquina houses are making way for modern hotels and winter residences.

In 1769, during the British occupation, a colony of Minorcan and Majorcans were brought from the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea to New Smyrna, on the Indian River, south of St Augustine. Deceived by Turnbull, the proprietor of the plantation, and subjected to gross privation and cruelty, the Minorcans at length appealed to the authorities of St. Augustine, were promised protection, deserted from New Smyrna in a body, came to St Augustine, were defended against the claims of Turnbull. received an allotment of land in the town, built palmetto-thatched cottages and remained here after the English emigrated.

The pathetic story of the Minorcans at New Smyrna and their exodus to St, Augustine has enlisted the sympathetic pen of more than one narrator, There is little reason for questioning the truth of the commonly accepted version, yet it is due to Dr. Turnbull to remember that this story, like every other, has two sides. Turnbull's side is given by his personal friend Dr. Johnson of Charleston, S. C., in his Reminiscences of the American Revolution. According to this authority the New Smyrna revolt was instigated by the British Governor's wife, in St. Augustine, who had been an old flame of Turnbull's in Scotland, and was impelled to her mischief-making among his indentured colonists by a motive no less powerful than the fury of a woman scorned. Most travelers have spoken kindly of the Minorcans in St. Augustine. from Latrobe in 1832. who gives a pretty picture of the fishermen's cottages, festooned with nets and roses, shaded by orange trees and hung round with cages of nonpareils and mockingbirds, to William Cullen Bryant in 1843, who described them as "a mild, harmless race, of civil manners and abstemious habits." Five years later. Rev. R. K. Sewall, then the rector of Trinity Church, published his Sketches of St. Augustine. Should you ever come upon a copy of this book, it will almost certainly be found that pages 39 and 40 are wanting; and inspection will show that the leaf has been cut out, The missing pages contained this reference to the Minorcans:However big or little may have been the grains of truth in this description, the Minorcans had at least education enough to comprehend the uncomplimentary tone of Mr. Sewall's allusion to them; and when the edition of Sketches came to hand they showed their enterprise by mobbing the store where the books were, bent on the destruction of the whole lot. They were only restrained by a pledge, faithfully kept, that the obnoxious pages should be torn from every book.The present race were of servile extraction. By the duplicity of one Turnbull they were seduced from their homes in the Mediterranean and located at Smyrna, and forced to till the lands of the proprietors who had brought them into Florida for that purpose. After enduring great privation, toil and suffering, under the most trying circumstances of a servile state, they revolted in a body, regained their rights and maintained them. * * * Their women are distinguished for their taste, neatness and industry, a peculiar light olive shade of complexion, and a dark full eye. The males are less favored by nature and habit. They lack enterprise. Most of them are without education, Their canoes, fishing lines and hunting guns are their main source of subsistence. The rising generation is, however, in a state of rapid transition -- R. K. Sewall, "Sketches of St. Augustine," pp. 39-40.

Among the customs of the native land retained to a recent period by the Minorcans was the singing of a hymn in honor of the Virgin, by groups of young men who went about the streets serenading their friends, on the evening before Easter.

Actual Minorcans in St. Augustine shared a history of successful resistance to oppression and enslavement that connected them with the American narrative of struggling for self-determination and establishing democracy. Local residents and readers familiar with this history may see its traces in Jim's fierce independence. Jewett, however, emphasizes how his ethnicity affects his temperament. Jim's intemperance and his lack of self-control are associated with his black Spanish scowl. Jim explains to Marty:

"The devil gets me," said Jim at last, in a sober-minded Northern way that he had sometimes. "There's an awful wild streak in me. I ain't goin' to have you cry like mother always done. I'm goin' to settle down an' git a steady job ashore, after this one v'y'ge to the islands. I'm goin' to fetch ye home the handsomest basketful of shells that ever you see, an' then I'm done with shipping, I am so."He goes on to blame his boss, the captain of the Dawn of Day, for leading him astray by commanding him as a drinking partner. Marty and Jim both seem to believe that ill-behaved companions and indulgence in alcohol bring out Jim's darker side, and they associate this side of his personality with his Spanish / Minorcan ancestry. Self-control in this passage is associated with being Northern and sober-minded. However, the story as a whole questions this simplistic opposition.

A main voice for self-control in the story is the Bishop, who first calls upon Jim to realize the wish of another "little woman," his dead mother:

The bishop stopped Jim one day on the plaza, and told him that he must come to church sometimes for his mother's sake: she was a good little woman, and had said many a prayer for her boy. ... "Marry you a good wife soon," said the kind bishop. "Be a good man in your own town; you will be tired of roving and will want a home. God have pity on you, my boy!"Then, repeatedly through the story, the Bishop's voice recurs, issuing the warning that Jim will break Marty's heart if he does not reform, and finally blessing the couple when the redeemed Jim returns as if from the dead. Jim's Spanish/Minorcan ancestry and his Catholicism come to him through his mother from his grandmother. Jim's wildness seems more directly "inherited" from his Yankee grandfather, also an intemperate and moody man, and perhaps from his father, who deserted his young family. A Yankee background is really no guarantee of virtue or restraint, and northerners also are targets of ridicule, for example, for their "enthusiastic, money-squandering." Furthermore, insofar as his bad behavior arises in association with the hard life of local sailors and other male friends, Jewett may be pointing at Jim's entanglement in conflicting ideas of masculinity, as represented by Jim's two main masculine role models, the Bishop and the Captain.

The story as a whole, then, undercuts the opposition of Northerner and Spanish that at least some of the characters use to explain Jim's moods, suggesting that a more relevant opposition may be between versions of masculinity and that Jim's Minorcan ancestry, rather than explaining his Spanish scowl, gives him the feminine sympathy that enables him to appreciate Marty's devotion and to restrain himself in order to preserve his family. This view of Jim's Minorcan ethnicity may correspond more exactly with the portrait of Minorcans that emerges from Reynolds's account in The Standard Guide.

"Marry you a good wife soon," said the kind bishop. "Be a good man in your own town; you will be tired of roving and will want a home. God have pity on you, my boy!"

"Ah, Jim, many's the prayer your pious mother said for you, and I myself not a few."

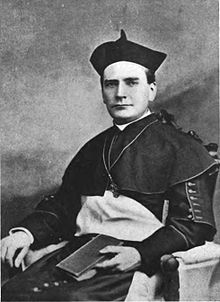

At the time the story is set, the Bishop was John Moore (1835-1901), who served as the second Bishop of St. Augustine 1877-1901. He continued his predecessor's active efforts to further Catholic education in St. Augustine and throughout Florida. Moore was born in Ireland and immigrated to Charleston, SC when he was 14. Reading his speeches out loud suggests that Jewett has given her bishop an Irish voice, though she does not render his speech in full dialect.

Wikipedia

Within the time-frame of the story, Bishop Moore would have been 55-57 years old. Jewett's narrator seems to imply that he is older, though this would be difficult to judge. Clearly, Jim sees him as older, perhaps in part because the Bishop was his mother's priest.

In this passage, Marty comes to understand that if she is to expect Jim to keep his temper, she must study to keep her own. Whether Marty's ancestry is Irish never is specified in the story, but many readers would have assumed so, based upon her pale complexion, red hair, and "peppery" temperament.She thought about Jim as she sat there; how good he was before he sailed that last time, and had really tried to keep his promise on board ship, according to the cabin-boy's story. Somehow Jim was like the moon to her at first; his Spanish blood and the Church gave an unknown side to his character that was always turned away; but another side shone fair through his Northern traits, and of late she had understood him as she never had before. She used to be too smart-spoken and too quick with him; she saw it all now; a quick man ought to have a wife with head enough to keep her own temper for his sake. "I couldn't help being born red-headed," thought Marty with a wistful smile, ...

But as with Jim's dual ancestry, the story as a whole does not affirm a simplistic association of Irish ethnicity and hot-headedness. Marty connects her short temper with her red hair, but when she loses her temper, the narrator speaks of "Northern fury":

Marty's Northern fury rose like a winter gale; she was vexed by the taunts of a woman who lived up the lane, who used to come out and sit on her high blue balcony and spy all their goings on, and call the baby poor child so that his mother could hear. Jim's little woman drove the ribald company out of doors that night, and they quailed, drunk as they were, before her angry eyes.The Irish Bishop's temper seems well under control. His personality exhibits kindliness, compassion, and patience with human frailty, as is made clear at the end of the story:

As they went home at sunset, they met the bishop, who stopped before them and looked down at the little woman, and then up at Jim.

"So you're doing well now, my boy?" he said good humoredly, to the great, smiling fellow. "Ah, Jim, many's the prayer your pious mother said for you, and I myself not a few. Come to Mass and be a Christian man for the sake of her. God bless you, my children!" and the good man went his wise and kindly way, not knowing all their story either, but knowing well and compassionately the sorrows and temptations of poor humanity.

Black

children at the Old Gate

Reynolds, p. 45

At last, one night, they made such a racket that a group of idle negroes clustered about the house, laughing and jeering at the company within. ... They chased the negroes in their turn, and went off shouting and swearing down the bayside. They tried to walk on the sea-wall, and one man fell over and was too drunk to find his way ashore, and lay down on the wet, shelly mud. The tide came up and covered Joe Black, and that was the last of him, ...

The first description of African Americans to appear in the story is also perhaps the most startling, for this is a potentially incendiary event that is comic in tone and tragic in outcome, but not in the way 21st-century readers might expect. A group of inebriated working-class "whites," at least one of whom is a short-tempered Minorcan sailor, becomes the objects of jeering and laughter from a group of Black men passing in the street by night. This would seem a recipe for fatal racial violence. Yet, this element is pointedly absent, there being no references to specifically racial animosity, no report of racial taunting or intimidation, no threats, no aftermath of mob retaliation against "uppity" Blacks. Instead, the drunken whites, after chasing off the Blacks, go their own way, and tragedy arises not from racism, but from intemperance. While the incident clearly reflects segregation, the white and Black men forming their own social groups, missing are the violence and intimidation that characterized Black-White relations in much of the United States at this time and that would bring racial terror to St. Augustine in the 1960s, as recounted by David Colburn.

One might hypothesize that Jewett here fails as historian, blinded by a wishful vision of racial and ethnic harmony in a southern tourist paradise with which she was not so familiar as with her native New England. She may have been diverted from her usually more perceptive insight into the darker sides of American life, as reflected in other stories she composed at about the same time, such as "The Mistress of Sydenham Plantation" (1888), "The Town Poor" (1890) and "In Dark New England Days" (1890).

As illustrated in part by "The Mistress of Sydenham Plantation," Jewett was not naive about the complexities of American racial relations in the Gilded Age. Nor was she likely to have been ignorant, for in the New York Times during the 1880s and 1890s one could read almost weekly about lynchings and riots, in which violence against African Americans is assumed to be normal. When a Black person is accused of a crime, it is "expected" that he will be lynched, even outside the former Confederacy. These stories also frequently report Black armed resistance, usually termed a "riot." Tolney and Beck, in A Festival of Violence, offer a sense of the number of such stories that could have appeared in the 1880s and 1890s.

1888 -- 53

1889 -- 53

1890 -- 46

1891 -- 83

1892 -- 92

1893 -- 99

The number of Black victims lynched by white mobs in the South generally increased at the same time that southern states were establishing a variety of "Jim Crow" laws to restrict and separate African Americans (271):

As an Episcopalian, Jewett probably was aware of conflict in the annual church conventions of southern states, notably in South Carolina in 1887-8, in which white lay representatives successfully "seceded" and forced the Bishop to form two conventions, one for Black and another for white Episcopalians (See Tindall 194-200, and in the New York Times, "The Color Line in Religion," 14 May 1887: 5; "The Episcopalian Secession" 15 May 1887: 1; and "The Race Question in Religion" 4 May 1888: 1). Given Jewett's implicit attitudes toward Native American Episcopalians in her early story, "Tame Indians," one imagines Jewett could only have been revolted by the petty inhumanity of white refusals to accept Black Episcopalians as their brothers and sisters in Christ. A list of New York Times headlines about racial troubles between February and June of 1888 can illustrate what "everyone knew" about the racial situation in the months of Jewett's first trip to St. Augustine:

2/6 -- Major M'Gill's Version: His story of the Jackson election troubles, He says no colored man dared to vote -- the circular of the Young White League, p. 1.Jewett almost certainly knew what every informed person knew about deteriorating race relations. When she and Fields visited with Laura Towne at the Penn School on St. Helena's Island, South Carolina, her understanding of racial intimidation likely deepened. Blanchard writes of Towne: "By 1888, her work was largely done and the community served as a model for others throughout the islands.... 'The result of her work lay like a map before us,' Annie wrote .... 'Every step spoke to us of the sacrifice and suffering of humanity and of its endurance in the present time'" (193-4). Though Blanchard does not detail what Jewett, Fields and Towne talked about during the stay, Fields's report suggests that the current situation of the former slaves was an important topic (see also Fields, "Laura M. Towne"). What Towne could have told them is clear in her own diary and letters, which repeatedly express fear that resurgent Democrats will succeed in invalidating African-American deeds to land on St. Helena's, where at the beginning of the Civil War, occupying Union forces had turned over abandoned plantations to former slaves. She documents, with anger and grief, the violence and intimidation by which South Carolina Democrats blatantly and proudly disenfranchised local Blacks and commandeered labor by arbitrary imprisonment. In a letter of 23 May 1880, Towne quotes Ishmael Williams, a visiting minister who has just inspected such a prison: "the Democrats must think there is no hell for bad people, for they make one of that prison." He describes horrific conditions at the prison and then quotes its keeper, "You have come, I suppose, to see how we take niggers down. I'll show you" (302). It is likely that by 1888 Towne felt even more strongly that a day of reckoning was approaching, when justice would come again for those who believe there is no hell for bad people.

2/24 -- Negro Rioters in Baltimore, p. 5.

3/1 -- Many Negroes Massacred, p. 1.

3/27 -- One Killed and Another Lynched, p. 5.

5/5 -- Negro Insurrection Not Feared, p. 2.

5/5 -- Several Negroes Killed, p. 1.

5/6 -- Few Southern Negroes Land Owners, p. 10.

5/10 -- An Alleged Negro Plot to Murder White People in Lowndes County, ALA, p. 6.

5/13 -- Would Not Serve a Negro, p. 14.

5/19 -- Hunting For a Negro, p. 5.

5/19 -- Assaulted by Negroes, p. 1.

5/21 -- The Leader Killed: A flogging party fired on from ambush, p. 1.

5/27 -- The Negro Improving in Looks, p. 4.

5/30 -- Think There's a Lynching Going On, p. 1.

5/30 -- Negroes Whip a White Man, p. 3.

6/4 -- A Colored Burglar Lynched, p. 2.

6/12 -- Three Negroes Lynched: They are taken from jail and meet prompt justice. p. 2

6/22 -- A Negro Lynched, p. 6.

6/27 -- A Negro Lynched, p. 2.

When Jewett and Annie Fields stayed in St. Augustine in 1890, they were able to ride the newly finished railway directly from New York to St. Augustine. Though segregated travel was common throughout the United States, in the 1880s and 1890s southern states passed laws requiring such segregation. Florida's law went into effect in 1887. Jewett and Fields likely witnessed the removal of Blacks from general seating to Jim Crow cars upon entering states that required such segregation (See Railroads and the Making of Modern America). And they also would note segregated waiting rooms in the stations. While Henry Flagler oversaw his railroad's enforcement of segregation laws, he was anxious to keep this enforcement low key. Graham reports, for example, that Flagler wanted to avoid using signs to designate separate waiting rooms and that he managed difficult problems such as visits of Black dignitaries to Florida and transportation of his large African American hotel seasonal staffs by providing them with private cars (Chapter 19).

While one might suspect that Jewett lacked knowledge about the state of Black - White relations in America and the South in particular, it would be naive to consider her so unaware of what everyone else knew, including her closest friend, Annie Fields, who initiated the visit to her old friend, Laura Towne. Perhaps, then, Jewett failed to penetrate a studied surface of racial harmony to see the system of violence and intimidation by which it was maintained, and this failure allowed her to imagine a fantasy in which Blacks and Whites engage in an explosive encounter that miraculously does not detonate.

The appearance of racial harmony in St. Augustine was studied. The city leadership was eager to project the most positive image of the city in which their businesses depended upon the annual influx of tourists who expected a safe and healthy escape from northern winter. Henry Flagler wanted to fill his luxury hotels with high-paying guests. To do this successfully, he favored a large number of Black employees, from whom he wanted loyalty and circumspection. As Thomas Graham (2014) shows, Flagler -- though he shared the general American belief in white racial superiority -- nevertheless was careful to treat his Black employees with dignity and respect. Though he exploited them as entertainers as well as servants of his guests. Flagler paid them well and looked out for their general welfare (See Chapters 13 and 19). St. Augustine, for a time before the turn of the 20th century, was one of the better communities for African Americans. David Colburn describes this period as one of mutual dependency between the Black and White communities that fostered peaceful relations. Neighborhoods were not rigidly segregated. Blacks and whites were acquainted with each other, and leaders often worked together. Elected Blacks served on the city council. There were no lynchings in or near St. Augustine until 1897, and there was a relatively low level of violence and intimidation in evidence. This situation held up fairly well until after World War 1, when Black out-migration from St. Augustine was lower than in most of the rest of the South (18-20, See also James Smith, 11-13).

The appearance of racial harmony in St. Augustine in 1890 reflected reality to a considerable degree. Jewett's presentation of a potential racial conflict that does not flare up is not merely a wishful fantasy, but a reasonably accurate reflection of racial relations in St. Augustine in 1890. Though life for Blacks in St. Augustine was far from ideal, at the time that Jewett and Fields vacationed in Florida, race relations seem to have been significantly better than elsewhere, and these circumstances made it possible for this incident in Jewett's story to reflect the historical reality of the moment. That moment was fading, however. As Colburn acknowledges, few whites in St. Augustine believed in equality of the races and, though segregation in 1890 was neither rigid nor absolute, Jim Crow laws were passing through the Florida legislature and taking stronger hold through the 1890s. Colburn points out that by 1900, the Black wait staff that Flagler preferred in his hotels had been replaced by whites. As Colburn and Smith make clear, there were undercurrents of anger and resistance. African Americans in St. Augustine were not happy with the growing restrictions of Jim Crow. Graham recounts incidents illustrating indignities that Blacks suffered when they were perceived to be encroaching upon white privilege; see, for example, the account of a Black mason who was ostracized by his white co-workers during the building of the Ponce de Leon (108-9). Jewett seems to have caught the city in her lens during one of its better times.

African American boy at the Plaza Basin

Reynolds, p. 16

Two African American Characters: the Nanny and the Witch

There was a quiet little colored girl, an efficient midget of a creature, who had minded babies for a white woman in Baya Lane, and was not without sage experience.An important minor character is the African American "girl" Marty hires to care for her children. Whether she really is a girl by age remains unclear. Like Marty, she is a little woman, completing a trio of Jim's "little women": mother, wife, and nanny to his children. Marty does not always get along well with everyone, notably the neighbor woman of the "blue balcony," who seems to judge Marty negatively at first, but later becomes her supportive friend. But it seems clear that Marty and her black helper cooperate without tension, presumably because the woman mirrors Marty in more ways than in her size. As the above passages indicate, the nanny is quiet, efficient, knowledgeable, experienced, patient and hard-working, a "colored" version of Marty.

The hired help pushed the empty perambulator with all the strength she could muster through the deep white sand, and over the huge green, serpent-like vines that wound among the low dunes.

That Jewett gives Marty's hired help no name and refers to her as a girl, though she is likely close to Marty in age, could be troubling if viewed outside the context of the whole story. In fact, no characters in the story, other than Jim and Marty, are named, not even the Bishop and the ship's boy, who are the only characters, aside from Jim and Marty, to have significant speaking parts. Perhaps Jewett made this choice in part to forestall speculation about any real people, such as the Bishop, who appear in the story. While calling Marty's black help a girl could be condescending, the narrator is consistent through the story in referring to all young, unmarried women as girls, including Marty's fellow workers in the Maine canning factory and the young women who room at her house during Jim's long absence.

She had been thinking of Jim, and of her afternoon's affairs, and of a strange little old negro woman who had been looking out of a doorway on George Street, as she passed. It seemed to Marty as if this old withered creature could see ghosts in the street instead of the live passers-by. She never looked at anybody who passed, but sometimes she stood there for an hour looking down the street and mumbling strange words to herself. Jim's little woman was not without her own superstitions; she had been very miserable of late about Jim, and especially since she found his lucky shell. If she could only see him coming home in her dream; she had always dreamed of him before!The African American "witch," yet another little woman, makes a very brief appearance. Characterizing this woman as a witch comes entirely from Marty, who interprets her aged appearance and somewhat odd behavior. To Marty it seems as if the woman is seeing and communicating with invisible people rather than those who are physically present. However, the narrator's odd locution tends to affirm Marty's interpretation: "Jim's little woman was not without her own superstitions." The narrator accords superstition to both women. In addition to believing in the old woman's supernatural powers, Marty believes in the lucky shell that she and Jim share and that her recurrent dream of Jim's returns from voyages is prophetic.

The elderly black woman is not distinguished from whites in the story by the suggestion that she may have some supernatural power of perception, since Marty believes that she, herself, has a similar power. The two are different in that the witch seems to Marty to actively engage in her superstition, with her apparent incantations, while Marty is a passive receiver of her prophetic dream and of whatever luck her shell gives her.

Suddenly she became aware that all the little black boys were running through the streets like ants, with single bananas, or limp, over-ripe bunches of a dozen; and she turned quickly, running a few steps in her eagerness to see the bay.This short passage suggests a good deal about African American life in St. Augustine. This event begins Marty's discovery that the crew of the Dawn of Day believes Jim has died in Jamaica, the moment when she realizes that Jim's ship is in the harbor. The instant when the black boys stand out from the rest of the people on the busy streets occurs because they are running, because they are carrying over-ripe bananas, and because these facts signal to Marty the arrival of a ship. Ordinarily, they would blend in with the cosmopolitan crowd, but they are made to stand out by a sign of their low economic and social class position, by their being the ones who have some claim on low quality, free food to be expected when a freight ship from the Bahamas unloads.

This telling detail indicates that while Jewett recognized the unusual racial harmony in St. Augustine in 1890, she also was aware that African Americans lived at a lower economic level than most whites.

It was a sad summer, -- a sad summer. Marty knew that her neighbors thought her a little crazed; at last she wondered if they were not right. She began to be homesick, and at last she had to give up work altogether. She hated the glare of the sun and the gay laughter of the black people; when she heard the sunset gun from the barracks it startled her terribly. She almost doubted sometimes whether she had really dreamed the dream.This passage describes Marty's psychological state at her lowest point, when she is near to accepting that Jim is indeed dead and that she will have to struggle on, caring for her children without her husband. The passage names three irritants to her weakened nerves: the summer glare, the sunset cannon firing, and "the gay laughter of the black people." Why should the laughter of African Americans be distinguished from the laughter of any other individual or group? Is Marty's reaction informed by the stereotype of Blacks as particularly able to shed their troubles and enjoy the pleasure of the moment unalloyed? As she finds her situation increasingly unbearable, it could be difficult to witness others seeming to cope effortlessly, as if they were immune to suffering. How the African American presence functions in this passage is difficult to tease out.

The great bell of the old cathedral had struck twelve, and as Marty entered the plaza, busy little soul that she was and in a hurry as usual, she stopped, full of a never outgrown Northern wonder at the foreign sights and sounds, -- the tall palmettoes; the riders with their clinking spurs; the gay strangers; the three Sisters of St. Joseph, in their quaint garb of black and white, who came soberly from their parish school close by.

The Sisters of St. Joseph, St. Augustine

Their quaint garb of black and white.

The Sisters of St. Joseph were invited to St. Augustine to "teach literacy" to newly freed slaves after the American Civil War. According to the history of the St. Joseph Academy, the school was founded in 1866 by Augustin Verot, First Bishop of St. Augustine, who invited the French Sisters of St. Joseph to operate it. The parish school of St. Joseph in this story, then, would have been a Freedmen's school staffed mainly by French nuns. From early on located on St. George Street, adjacent to the Sisters of St. Joseph Convent and near the plaza, the academy moved to 155 State Road 207 in 1980. In 1898, a new school was built in Lincolnville, at the south end of the old city, St. Benedict the Moor. Staffed by the Sisters of St. Joseph, this became one of the city's main schools for Black children until schools were integrated in 1964.

Site of the St. Joseph Academy,

convent visible on far right.

The Sisters of St. Joseph convent remains at 241 St. George Street.

According to Mary Atwood and William Weeks in Historic Homes of Florida's First Coast (89-92), the original convent and school were in the Father O'Reilly house at 32 Aviles St.

The Father O'Reilly house at 32 Aviles St.,

site of the original convent and school of the Sisters of St. Joseph in St. Augustine.

Why does Jewett take the trouble to mention the Sisters of St. Joseph in this story?

The Cuban Giants were among several black baseball teams to play for the entertainment of Flagler hotel guests. Some team members were hotel staff. Henry Flagler constructed a baseball field near the hotels for these and other exhibition games (Graham 2014, Chapters 11, 13).

Jewett's Witchcraft: Seeing Invisible Presences

Thomas Graham quotes this statement in his account of Henry Flagler's use of Black waiters in his hotels (2014, Chapter 12). Though Flagler's treatment of black hotel employees seems enlightened and considerate for his time, there is ample evidence that he took care to control their visibility to hotel patrons. Employees were under orders to take routes from their dormitories to the hotels that would minimize their visibility to patrons. Black employees in particular were made visible upon designated occasions, such as when they entertained guests in cake walks, minstrel shows, and baseball games.

Similarly, the presence of African Americans in Reynolds's Standard Guide also is carefully controlled. They are virtually invisible in the text, where it is noted that Negro troops occupied Fort Matanzas during the second Spanish supremacy (84), and they are mentioned again when Reynolds disputes the assertion that the market building in the plaza was at one time a slave market (47). In his illustrations, Reynolds includes just two clear images of African Americans, the two images above in which black children appear, fairly clearly as elements of the sort of local color tourists may expect to see. In this respect, they share with the Minorcans a visibility mainly as exotic aspects of the scenery, the only image of a Minorcan in Reynolds being the drawing above of "A Woman of the Balearic Islands," by Gustave Doré (19). Reynolds does not include an account of Fort Mose, an important site in African American history, but in 1890 generally forgotten. Nor does General Jorge Biassou (1741-1801), an important Black historical figure, appear in Reynolds's guide.

Furthermore, African Americans are virtually invisible in contemporary collections of images of St. Augustine, such as Picturesque St. Augustine 1891 by Edward Bierstadt and the Library of Congress collection of Detroit Publishing Company photographs. Beth Bowen's St Augustine in the Gilded Age, presents historical postcard images of St. Augustine, only two of which seem clearly to include Black people. In one of these several follow a parade (105), and in the other, they inspect the ruins of a 1914 fire (110). Though she makes clear that the Sisters of St. Joseph taught freedmen after the Civil War, Bowen is not able to show a postcard image of the freedman's school, only of the academy buildings for white students, erected after the establishment of the St. Benedict the Moor school for black children.

In short, African Americans were, on the whole, invisible in the white world of Gilded Age St. Augustine, even though they were a very significant presence. When they became visible to whites was controlled to minimize their importance and to define them as exotic and entertaining features of a tourist destination.

In contrast, Jewett records African American residents and workers in St. Augustine as important parts of the population. The young men who taunt Jim and his drunken friends clearly are reasonably secure members of the community who are not making any obvious effort to minimize their own visibility. The nanny is one of the three little women who contribute to Jim and Marty successfully repairing their early errors. The witch, though perhaps more exotic than the others, is a prominent and visible citizen. The black boys with their bananas clearly are always present in the crowd, but become visible when they separate themselves and run through the street. Jewett shows in her setting and characters some of those people who lack official visibility in other documents.

Jewett also calls attention to the Irish Bishop's humane wisdom as her moral hero sympathetically admonishes and encourages the weak and erring couple in their quest to create a family. She brings before readers the French nuns whose current local mission is the education of black children.

Further, Jewett both presents and subverts ethnic stereotypes. Though she notes the tendencies of her characters to use exotic Irish and Minorican ethnic stereotypes to account for some behaviors, the story undercuts such explanations and gives readers the Minorcan Jim and Irish Marty as flawed human beings working to remake themselves into a successful family.

Contemporary photos also by Terry Heller, February 2015.

Copyright: May 2015

Main Contents & Search

A Native of Winby