Strangers & Wayfarers

Main Contents & Search

Atlantic Text

A high wind was blowing from the water into the Beaufort streets, -- a wind with as much reckless hilarity as March could give to her breezes, but soft and spring-like, almost early-summer-like, in its warmth.

In the gardens of the old Southern houses that stood along the bay, roses and petisporum-trees were blooming, with their delicious fragrance. It was the time of wistarias and wild white lilies, of the last yellow jasmines and the first Cherokee roses. It was the Saturday before Easter Sunday.

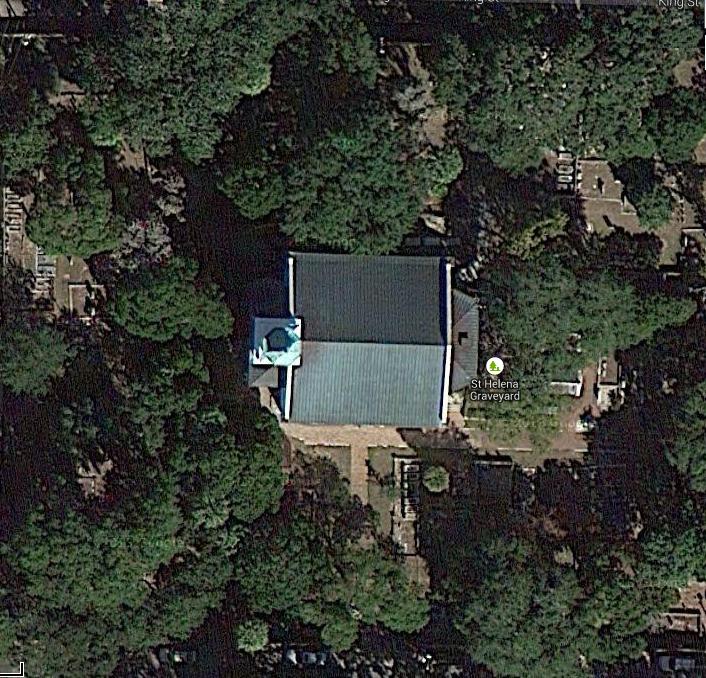

In the quaint churchyard of old St. Helena's Church, a little way from the bay, young figures were busy among the graves with industrious gardening. At first sight, one might have thought that this pretty service was rendered only from loving sentiments of loyalty to one's ancestors, for under the great live-oaks, the sturdy brick walls about the family burying-places and the gravestones themselves were moss-grown and ancient-looking; yet here and there the wounded look of the earth appealed to the eye, and betrayed a new-made grave. The old sarcophagi and heavy tablets of the historic Beaufort families stood side by side with plain wooden crosses. The armorial bearings and long epitaphs of the one and the brief lettering of the other suggested the changes that had come with the war to these families, yet somehow the wooden cross touched one's heart with closer sympathy. The padlocked gates to the small inclosures stood open, while gentle girls passed in and out with their Easter flowers of remembrance. On the high churchyard wall and great gate-posts perched many a mocking-bird, and the golden light changed the twilight under the live-oaks to a misty warmth of color. The birds began to sing louder; the gray moss that hung from the heavy boughs swayed less and less, and gave the place a look of pensive silence.

In the church itself, most of the palms and rose branches were already in place for the next day's feast, and the old organ followed a fresh young voice that was being trained for the Easter anthem. The five doors of the church were standing open. On the steps of that eastern door which opened midway up the side aisle, where the morning sun had shone in upon the white faces of a hospital in war-time, -- in this eastern doorway sat two young women.

"I was just thinking," one was saying to the other, "that for the first time Mistress Sydenham has forgotten to keep this day. You know that when she has forgotten everything and everybody else, she has known when Easter came, and has brought flowers to her graves."

"Has she been more feeble lately, do you think?" asked the younger of the two. "Mamma saw her the other day, and thought that she seemed more like herself; but she looked very old, too. She told mamma to bring her dolls, and she would give her some bits of silk to make them gowns. Poor mamma! and she had just been wondering how she could manage to get us ready for summer, this year, -- Célestine and me," and the speaker smiled wistfully.

"It is a mercy that the dear old lady did forget all that happened;" and the friends brushed some last bits of leaves from their skirts, and rose and walked away together through the churchyard.

The ancient church waited through another Easter Even, with its flowers and long memory of prayer and praise. The great earthquake had touched it lightly, time had colored it softly, and the earthly bodies of its children were gathered near its walls in peaceful sleep.

From one of the high houses which stood fronting the sea, with their airy balconies and colonnades, had come a small, slender figure, like some shy, dark thing of twilight out into the bright sunshine. The street was empty, for the most part; before one or two of the cheap German shops a group of men watched the little old lady step proudly by. She was a very stately gentlewoman, for one so small and thin; she was feeble, too, and bending somewhat with the weight of years, but there was true elegance and dignity in the way she moved, and those who saw her -- persons who shuffled when they walked, and boasted loudly of the fallen pride of the South -- were struck with sudden deference and admiration. Behind the lady walked a gray-headed negro, a man who was troubled in spirit, who sometimes gained a step or two, and offered an anxious but quite unheeded remonstrance. He was a poor, tottering old fellow; he wore a threadbare evening coat that might have belonged to his late master thirty years before.

The pair went slowly along the bay street to the end of a row of new shops, and the lady turned decidedly toward the water, and approached the ferry-steps. Her servitor groaned aloud, but waited in respectful helplessness. There was a group of negro children on the steps, employed in the dangerous business of crab-fishing; at the foot, in his flat-bottomed boat, sat a wondering negro lad, who looked up in apprehension at his passengers. The lady seemed like a ghost. Old Peter, -- with whose scorn of modern beings and their ways he was partially familiar, -- old Peter was making frantic signs to him to put out from shore. But the lady's calm desire for obedience prevailed, and presently, out of the knot of idlers that gathered quickly, one, more chivalrous than the rest, helped the strange adventurers down into the boat. It was the fashion to laugh and joke, in Beaufort, when anything unusual was happening before the eyes of the younger part of the colored population; but as the ferryman pushed off from shore, even the crab-fishers kept awe-struck silence, and there were speechless, open mouths and much questioning of eyes that showed their whites in vain. Somehow or other, before the boat was out of hail, long before it had passed the first bank of raccoon oysters, the tide being at the ebb, it was known by fifty people that for the first time in more than twenty years the mistress of the old Sydenham plantation on St. Helena's Island had taken it into her poor daft head to go look after her estates, her crops, and her people. Everybody knew that her estates had been confiscated during the war; that her people owned it themselves now, in three and five and even twenty acre lots; that her crops of rice and Sea Island cotton were theirs, planted and hoed and harvested on their own account. All these years she had forgotten Sydenham, and the live-oak avenue, and the outlook across the water to the Hunting Islands, where the deer ran wild; she had forgotten the war; she had forgotten her children and her husband, except that they had gone away, -- the graves to which she carried Easter flowers were her mother's and her father's graves, -- and her life was spent in a strange dream.

Old Peter sat facing her in the boat; the ferryman pulled lustily at his oars, and they moved quickly along in the ebbing tide. The ferryman longed to get his freight safely across; he was in a fret of discomfort whenever he looked at the clear-cut, eager face before him in the stern. How still and straight the old mistress sat! Where was she going? He was awed by her presence, and took refuge, as he rowed, in needless talk about the coming of the sandflies and the great drum-fish to Beaufort waters. But Peter had clasped his hands together and bowed his old back, as if he did not dare to look anywhere but at the bottom of the boat. Peter was still groaning softly; the old lady was looking back over the water to the row of fine houses, the once luxurious summer homes of Rhetts and Barnwells, of many a famous household now scattered and impoverished. The ferryman had heard of more [one than] than one bereft lady or gentleman who lived in seclusion in the old houses. He knew that Peter still served a mysterious mistress with exact devotion, while most of the elderly colored men and women who had formed the retinues of the old families were following their own affairs, far and wide.

"Oh, Lord, ole mis'! what kin I go to do?" mumbled Peter, with his head in his hands. "Thar'll be nothin' to see. Po' ole mis', I do' kno' what you say. Trouble, trouble!"

But the mistress of Sydenham plantation had a way of speaking but seldom, and of rarely listening to what any one was pleased to say in return. Out of the mistiness of her clouded brain a thought had come with unwonted clearness. She must go to the island: her husband and sons were detained at a distance; it was the time of year to look after corn and cotton; she must attend to her house and her slaves. The remembrance of that news of battle and of the three deaths that had left her widowed and childless had faded away in the illness it had brought. She never comprehended her loss; she was like one bewitched into indifference; she remembered something of her youth, and kept a simple routine of daily life, and that was all.

"I t'ought she done fo'git ebryt'ing," groaned Peter again. "O Lord, hab mercy on ole mis'!"

The landing-place on Ladies' Island was steep and sandy, and the oarsman watched Peter help the strange passenger up the ascent with a sense of blessed relief. He pushed off a little way into the stream, for better self-defense. At the top of the bluff was a rough shed, built for shelter, and Peter looked about him eagerly, while his mistress stood, expectant and imperious, in the shade of a pride of India tree, that grew among the live-oaks and pines of a wild thicket. He was wretched with a sense of her discomfort, though she gave no sign of it. He had learned to know by instinct all that was unspoken. In the old times she would have found four oarsmen waiting with a cushioned boat at the ferry; she would have found a saddle-horse or a carriage ready for her on Ladies' Island for the five miles' journey, but the carriage had not come. The poor gray-headed old man recognized her displeasure. He was her only slave left, if she did but know it.

"Fo' Gord's sake, git me some kin' of a cart. Ole mis', she done wake up and mean to go out to Syd'n'am dis day," urged Peter. "Who dis hoss an' kyart in de shed? Who make dese track wid huffs jus' now, like dey done ride by? Yo' go git somebody fo' me, or she be right mad, shore."

The elderly guardian of the shed, who was also of the old régime, hobbled away quickly, and backed out a steer that was broken to harness, and a rickety two-wheeled cart. Their owner had left them there for some hours, and had crossed the ferry to Beaufort. Old mistress must be obeyed, and they looked toward her beseechingly where she was waiting, deprecating her disapproval of this poor apology for a conveyance. The lady long since had ceased to concern herself with the outward shapes of things; she accepted this possibility of carrying out her plans, and they lifted her light figure to the chair, in the cart's end, while Peter mounted before her with all a coachman's dignity, -- he once had his ambitions of being her coachman, -- and they moved slowly away through the deep sand.

"My Gord A'mighty, look out fo' us now," said Peter over and over. "Ole mis', she done fo'git, good Lord, she done fo'git how de Good Marsa up dere done took f'om her ebryt'ing; she 'spect now she find Syd'n'am all de same like 's it was 'fo' de war. She ain't know 'bout what's been sence day of de gun-shoot on Port Royal and dar-away. O Lord A'mighty, yo' know how yo' stove her po' head wid dem gun-shoot; be easy to ole mis'."

But as Peter pleaded in the love and sorrow of his heart, the lady who sat behind him was unconscious of any cause for grief. Some sweet vagaries in her own mind were matched to the loveliness of the day. All her childhood, spent among the rustic scenes of these fertile Sea Islands, was yielding for her now an undefined pleasantness of association. The straight-stemmed palmettos stood out with picturesque clearness against the great level fields, with their straight furrows running out of sight. Figures of men and women followed the furrow paths slowly; here were men and horses bending to the ploughshare, and there women and children sowed with steady hand the rich seed of their crops. There were touches of color in the head kerchiefs; there were sounds of songs as the people worked, -- not gay songs of the evening, but some repeated line of a hymn, to steady the patient feet and make the work go faster, -- the unconscious music of the blacks, who sing as the beetle drones or the cricket chirps slowly under the dry grass. It had a look of permanence, this cotton-planting. It was a thing to paint, to relate itself to the permanence of art, an everlasting duty of mankind; terrible if a thing of force and compulsion and for another's gain, but the birthright of the children of Adam, and not unrewarded nor unnatural when one drew by it one's own life from the earth.

Peter glanced through the hedge-rows furtively, this way and that. What would his mistress say to the cabins that were scattered all about the fields now, and that were no longer put together in the long lines of the quarters? He looked down a deserted lane, where he well remembered fifty cabins on each side of the way. It was gay there of a summer evening; the old times had not been without their pleasures, and the poor old man's heart leaped with the vague delight of his memories. He had never been on the block; he was born and bred at old Sydenham; he had been trusted in house and field.

"I done like dem ole times de best," ventures Peter, presently, to his unresponding companion. "Dere was good 'bout dem times. I say I like de ole times good as any. Young folks may be a change f'om me."

He was growing gray in the face with apprehension; he did not dare to disobey. The slow-footed beast of burden was carrying them toward Sydenham step by step, and he dreaded the moment of arrival. He was like a mesmerized creature, who can only obey the force of a directing will; but under pretense of handling the steer's harness, he got stiffly to the ground to look at his mistress. He could not turn to face her, as he sat in the cart; he could not drive any longer and feel her there behind him. The silence was too great. It was a relief to see her placid face, and to see even a more youthful look in its worn lines. She had been a very beautiful woman in her young days. And a solemn awe fell upon Peter's tender heart, lest the veil might be lifting from her hidden past, and there, alone with him on the old plantation, she would die of grief and pain. God only knew what might happen! The old man mounted to his seat, and again they plodded on.

"Peter," said the mistress, -- he was always frightened when she spoke, -- "Peter, we must hurry. I was late in starting. I have a great deal to do. Urge the horses."

"Yas, mis', -- yas, mis'," and Peter laughed aloud nervously, and brandished his sassafras switch, while the steer hastened a little. They had come almost to the gates.

"Who are these?" the stately wayfarer asked once, as they met some persons who gazed at them in astonishment.

"I 'spect dem de good ladies f'om de Norf, what come down to show de cullud folks how to do readin'," answered Peter bravely. "It do look kind o' comfo'ble over here," he added wistfully, half to himself. He could not understand even now how oblivious she was of the great changes on St. Helena's.

There were curious eyes watching from the fields, and here by the roadside an aged black woman came to her cabin door.

"Lord!" exclaimed Peter, "what kin I do now? An' ole Sibyl, she's done crazy too, and dey'll be mischievous together."

The steer could not be hurried past, and Sibyl came and leaned against the wheel. "Mornin', mistis," said Sibyl, "an' yo' too, Peter. How's all? Day ob judgment's comin' in mornin'! Some nice buttermilk? I done git rich; t'at's my cow," and she pointed to the field and chuckled. Peter felt as if his brain were turning. "Bless de Lord, I no more slave," said old Sibyl, looking up with impudent scrutiny at her old mistress's impassive face. "Yo' know Mars' Middleton, what yo' buy me f'om? He my foster-brother; we push away from same breast. He got trouble, po' gen'elman; he sorry to sell Sibyl; he give me silver dollar dat day, an' feel bad. ["] Neber min', I say. I get good mistis, young mistis at Sydenham. I like her well, I did so. I pick my two hunderd poun' all days, an' I ain't whipped. Too bad sold me, po' Mars' Middleton, but he in trouble. He done come see me last plantin'," Sibyl went on proudly. "Oh, Gord, he grown ole and poor-lookin'. He come in, just in dat do', an' he say, 'Sibyl, I long an' long to see you, an' now I see you;' an' he kiss an' kiss me. An' [dere 'sone] dere's one wide ribber o' Jordan, an' we'll soon be dere, black an' white. I was right glad I see ole Mars' Middleton 'fore I die."

The old creature poured forth the one story of her great joy and pride; she had told it a thousand times. It had happened, not the last planting, but many plantings ago. It remained clear when everything else was confused. There was no knowing what she might say next. She began to take the strange steps of a slow dance, and Peter urged his steer forward, while his mistress said suddenly, "Good-by, Sibyl. I am glad you are doing so well," with a strange irrelevancy of graciousness. It was in the old days before the war that Sibyl had fallen insensible, one day, in the cotton-field. Did her mistress think that it was still that year, and -- Peter's mind could not puzzle out this awful day of anxiety.

They turned at last into the live-oak avenue, -- they had only another half mile to go; and here, in the place where the lady had closest association, her memory was suddenly revived almost to clearness. She began to hurry Peter impatiently; it was a mischance that she had not been met at the ferry. She was going to see to putting the house in order, and the women were all waiting. It was autumn, and they were going to move over from Beaufort; it was spring next moment, and she had to talk with her overseers. The old imperiousness flashed out. Did not Peter know that his master was kept at the front, and the young gentlemen were with him, and their regiment was going into action? It was a blessing to come over and forget it all, but Peter must drive, drive. They had taken no care of the avenue; how the trees were broken in the storm! The house needed -- They were going to move the next day but one, and nothing was ready. A party of gentlemen were coming from Charleston in the morning! --

They passed the turn of the avenue; they came out to the open lawn, and the steer stopped and began to browse. Peter shook from head to foot. He climbed down by the wheel, and turned his face slowly. "Ole mis'!" he said feebly. "Ole mis'!"

She was looking off into space. The cart jerked as it moved after the feeding steer. The mistress of Sydenham plantation had sought her home in vain. The crumbled fallen chimneys of the house were there among the weeds, and that was all.

On Christmas Day and Easter Day, many an old man and woman come into St. Helena's Church who are not seen there the rest of the year. There are not a few recluses in the parish, who come to listen to their teacher and to the familiar prayers, read with touching earnestness and simplicity, as one seldom hears the prayers read anywhere. This Easter morning dawned clear and bright, as Easter morning should. The fresh-bloomed roses and lilies were put in their places. There was no touch of paid hands anywhere, and the fragrance blew softly about the church. As you sat in your pew, you could look out through the wide-opened doors, and see the drooping branches, and the birds as they sat singing on the gravestones. The sad faces of the old people, the cheerful faces of the young, passed by up the aisle. One figure came to sit alone in one of the pews, to bend its head in prayer after the ancient habit. Peter led her, as usual, to the broad-aisle doorway, and helped her, stumbling himself, up the steps, and many eyes filled with tears as his mistress went to her place. Even the tragic moment of yesterday was lost already in the acquiescence of her mind, as the calm sea shines back to the morning sun when another wreck has gone down.

| "The Mistress of

Sydenham Plantation" was the lead piece in Atlantic

Monthly (62:145-150) in August 1888. This text is

from Strangers and Wayfarers (1890). Apparent

errors in the text have been corrected and indicated with

brackets. If you find errors in the text or items that

need annotation, please contact the site manager. Betty Jean Steinshouer's research indicates that Jewett visited Beaufort, in 1888, and met with Laura Towne, one of the first principals, at the Penn School during that visit. Penn School was founded during the Civil War to educate the newly freed slaves. See note below on the good ladies from the North. In Sarah Orne Jewett, Blanchard says that in January, 1888, Annie Fields contracted pneumonia and nearly died. Her doctor recommending warm weather, Fields decided to go to St. Augustine, Florida, with Jewett to help her. Though Blanchard says the pair made stops in South Carolina on way to Florida, Jewett's letter to her sister, Mary, of 23 March 1888, shows that stops in Aiken and Beaufort, SC, occurred during a leisurely return from Florida, after their stay in St. Augustine. At the Aiken lodgings, "they ran into the distinguished abolitionist Senator George Edmunds of Vermont.... " At St. Helena, "they stayed with Annie's old friend Laura Towne, a homeopathic physician and educator who, many years earlier, had established a clinic and school on the island for its large population of freed slaves. By 1888 her work was largely done, and the community served as a model for others throughout the islands.... 'The result of her work lay like a map before us,' Annie wrote .... 'Every step spoke to us of the sacrifice and suffering of humanity and of its endurance in the present time'" (193-4). Fields presents an account of her visit with Laura Towne in a memorial essay published in the Boston Evening Transcript upon Towne's death in 1901. [ Back ] |

/

|

|

Beaufort: Beaufort,

South Carolina (founded in 1711) is located at the

head of the Port Royal Sound on Port Royal Island, one

of the Sea Islands. In a March

31, 1888 letter to her sister, Mary, Jewett

wrote, "Sister has come to the prettiest place now

that ever was!" |

|

West side of St. Helena's Church, the main entrance. |

South side of St. Helena's, looking through the high gate posts toward the southern door, half way up the side aisle. |

East side of St. Helena's with mausoleum. |

petisporum-trees: This is a

variation on the scientific name of a genus of trees within the

rosales (rose) family. Pittosporum is a genus of

evergreen trees and shrubs, and is both the largest (200

species) and most widely spread genus of the family pittosporaceae.

(Source: Encyclopedia Britannica Online)

[ Back ]

Cherokee roses: Of the genus rosa,

this is the species laevigata. This climbing evergreen

rose produces long, thorny, vine-like canes that sprawl across

adjacent shrubs and other supports. The pure white single

flowers appear in spring and are densely arranged along the

length of the canes. The plant can reach 10 to 12 feet in height

and 15 or more feet wide. (Source: www.floridata.com)

[ Back ]

| Easter Sunday:

Christians celebrate the resurrection of Jesus

Christ on this day each spring. [ Back ] the war: The American Civil War, 1861-1865. In March 2008, Bob Barrett, Archivist at the Parish Archives and Libraries, The Parish Church of St. Helena (Episcopal) in Beaufort, SC, reported that the Easter ritual of renewing the gardening around graves has not been a practice at this church in recent years, nor is there a written or oral account of such a practice in the past. He suggests that Jewett's description may have derived from the custom of children "Flowering the Cross" in the churchyard on Maundy Thursday of Holy Week. [ Back ] |

|

mocking-bird: a North American

singing bird (Mimus polyglottos), remarkable for its

exact imitations of the notes of other birds. Its back is gray;

the tail and wings are blackish, with a white patch on each

wing; the outer tail feathers are partly white. The name is also

applied to other species of the same genus, found in Mexico,

Central America, and the West Indies. (Source: ARTFL Project:

1913 Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary)

[ Back ]

Southwest churchyard of St. Helena's with gated wrought-iron enclosure, live oaks, and sarcophagi. |

Southern door of St. Helena's |

Southeast churchyard of St. Helena's. |

touched it lightly:

Though it is easy and natural to assume that Jewett refers to

the Civil War when she speaks of the "great earthquake," that

turns out not to be the case. She almost certainly refers

to the Charleston earthquake of August/September 1886. Bob

Barrett, of St. Helena's Church, reports that damage from this

quake was extensive in the region, though the church was not

seriously harmed. He reports "A contemporary diary account

of the earthquake, by a member of the parish, recounts the

earthquake and aftershocks. Domestic servants piled

mattresses on the carriages, and the family slept at the

Beaufort River for nearly three weeks."

Wikipedia says: "The

Charleston Earthquake of 1886 was the largest quake to hit

the Southeastern United States.

It occurred at 9:50 p.m. on August 31, 1886,

and lasted just under a minute. The earthquake caused severe

damage in Charleston, South Carolina, damaging 2,000 buildings

and causing $6 million worth in damages, while in the whole city

the buildings were only valued at approximately $24 million.

Between 60 and 110 lives were lost. Some of the damage is still

seen today.

Major damage occurred as far away as Tybee

Island, Georgia (over 60 miles away) and structural damage was

reported several hundred miles from Charleston (including

central Alabama, central Ohio, eastern Kentucky, southern

Virginia, and western West Virginia). It was felt as far away as

Boston to the North, Chicago and Milwaukee to the Northwest, as

far West as New Orleans, as far South as Cuba, and as far East

as Bermuda.

Were Jewett referring t the war, her

characterization of its effects on the church would be

inaccurate. The church Jewett saw was much restored after

the Civil War. The St. Helena's website says: During

the Civil War, when Union forces occupied Beaufort in November

1861, the entire congregation fled. Initially during the

occupation, church services were held in St. Helena’s, but

eventually Federal troops converted the church to a hospital.

The church was stripped of its furnishings, marble tombstones

were brought in for use as operating tables, and the balconies

were decked over to make a second floor.

'On a visit after the war in 1866,… Bishop

Thomas noted that ‘the church was a wreck of its former self and

could not be used.’ Only a small marble font remains today of

the furnishings prior to the war. … A new roof was put on

the church in 1874, one-half of the expense being born by

friends of St. Peter’s, Perth Amboy, New Jersey. A new organ to

replace, on a smaller scale, that lost in the Civil War was

installed in 1876, officers of the U.S. Fleet assisting'

(History Committee, The History of the Parish Church

of St. Helena. Columbia, SC: The R.L. Bryan Company,

1990, p. xii.)

The original cedar box pews were replaced

with heart of pine benches.

The present altar was given by the officers,

and carved by the sailors, of the U.S.S. New Hampshire stationed

in Port Royal Sound during the Reconstruction."

Probably the church had no steeple at the

time Jewett visited. It was removed for safety in the

1860s and not restored until 1941.

The church history at the St. Helena's

website confirms Jewett's observations about the prosperity of

the parish before the war as reflected in the impressive

ante-bellum graves in the churchyard. The churchyard is

more or less as Jewett describes it, with its brick wall,

constructed in 1804, and its impressive graves.

Information about St. Helena's Church history may be found at

the church's website.

[ Back ]

raccoon oysters: U. S., a small,

brown-shelled oyster, Ostrea frons, found in clusters

off the shores of south-eastern North America. (Source: Oxford

English Dictionary). See Hunting Island photo below.

[ Back ]

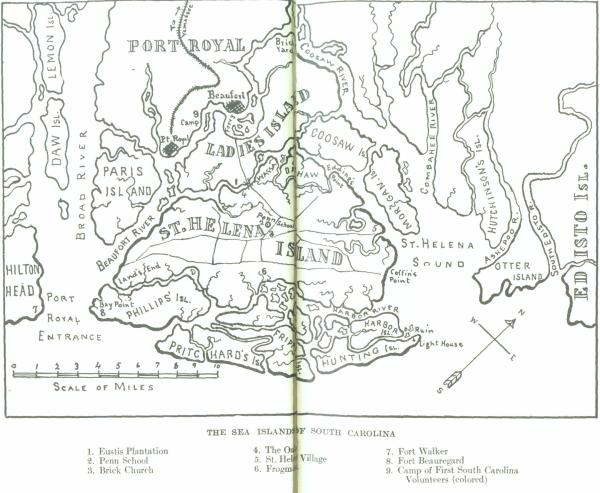

| St. Helena's

Island ... Sea Island ... Hunting Islands ... Ladies'

Island: The Sea Islands are a low-lying chain of

sandy islands off the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia,

and Florida, U.S., between the mouths of the Santee and

St. Johns rivers and along the Atlantic Intracoastal

Waterway. St.

Helena Island, near Beaufort, SC, is one of the

most prominent of these islands. Ladys (Ladies') Island

and Hunting Island also are near Beaufort and Port

Royal. The local geography is likely

to be confusing to readers not familiar with the area.

Mrs. Sydenham takes the ferry from Beaufort to Ladies'

Island, but when Peter mentions the teachers from the

North, he indicates they are then on St. Helena Island..

From Beaufort, the ferry would cross to Ladies' Island (now called Lady's). It appears that Peter and Sydenham cross Ladies' Island to reach St. Helena Island, presumably the location of the former Sydenham plantation. Sea Island cotton was of a special long-stranded variety, making it particularly valuable. After the Union gained control of the islands, it was eager to continue cotton production during the war. |

Current map courtesy of Encarta.msn. |

| Wikipedia says of St. Helena Island: "The area was noted to be similar to the rice growing region of West Africa and soon captured slaves were brought to the Sea Islands, mostly from what is today Sierra Leone. Rice, indigo, cotton and spices were grown by these slaves, as well as Native Americans, and indentured servants from Europe. The mix of cultures, somewhat isolated from the mainland, produced the Gullah culture." St. Helena Island was divided among the former slaves into small farms, such as those Jewett describes. Beaufort and St. Helena's interesting history, particularly the Penn School (see below), has, according to Wikipedia, "helped the defenders of the Gullah culture fend off the development that has turned other Sea Islands like Hilton Head into resort areas. Condos and gated communities are not allowed on St. Helena. Some rural land has been preserved and much of the island is still owned by African-Americans. However, economic pressures have forced some off their land, and may forever change the character of the area." |

Contemporary map is from Letters

and Diary of Laura M. Towne (1895). |

At the opening of Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne appears this contemporary description of the St. Helena's Island:

LOW-LYING cotton-fields, with here and there a sentinel palmetto; roads arched by moss-clad oak boughs; stretches of unclaimed timber and undergrowth; wide-sweeping marshes reflecting the moods and colors of the sky; the salt breath of the sea, softened by its passage over many islands; such is St. Helena. The cabins stand lonely and apart, most of them white, some painted pinks and reds. Here a woman, a bright bandana wound turban-like about her head, looks from her door; yonder the patriarchal figure of a man toils over the ploughed field. It is a land of great distances in a small compass, of soft colors, of a people utterly dependent on the soil and weather, primitive in their faith and courage, long-abiding, and wonderfully patient. Gratitude comes easily to their lips. Thankfulness for what they have received still seems the keynote of their lives.That Mrs. Sydenham has forgotten her traumatic past and lives with a sort of dementia under the care of her former slave recalls a Beaufort legend that may have provided Jewett with the idea for this story. Sources disagree about which elements of this story are true, but it is told in Beaufort as an illustration of the kindness and generosity the Sea Islands' African-American Civil War hero, statesman and local leader, Robert Smalls. Blogger Ron E. Franklin tells a full version of this story:

One day, some years after the Civil War, a frail, elderly woman came to the house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, South Carolina, and as she had done innumerable times before, went in. She was Jane Bold McKee, and she had lived in this house with her husband, Henry McKee, for many years.Andrew Billingsley, Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007), 103-4, tells part of this story, with some new and different details, placing Mrs. McKee in Smalls's household from 1875-1904. Edward A. Miller, Gullah Statesman: Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839-1915 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 127-8, expresses skepticism about several elements of the story. Whether the story is true is less important than that it was circulated in Beaufort and the Sea Islands and, therefore, it was quite possible that Towne or others at the Frogmore school would have shared with Annie Fields and Jewett such stories about Smalls, an active supporter of the school.

But by this point in her life, Jane McKee was afflicted with dementia. She didn’t remember that before the war her husband had sold the property. During the war it was seized by the Federal Government from the new owner, who had become a colonel in the Confederate army, for non-payment of taxes. When the war ended in April of 1865, the house once again changed hands, bought by a man who was already intimately familiar with the place. It would be interesting to know if Jane McKee ever understood that the man who sometimes brought meals to her room was one of the most celebrated and influential men in all of South Carolina, and indeed, the nation.

The new owner was Robert Smalls, a Union war hero who had been born, on April 5, 1839, in a two-room shack behind the McKee house. And he had once been Henry and Jane McKee’s slave.

Although they never freed him, the McKees had treated young Robert with extraordinary favor (it was rumored that Henry McKee was his father). Far from harboring any bitterness toward his former owners, Smalls saw the appearance of Jane McKee on his doorstep as an opportunity to give back. He opened his home to her, and she would spend the rest of her life living in the house she had loved, protected and provided for by the man who used to be her slave.

[ Back ]

sandflies: A member of the order Ephemeroptera, comprising the group of insects known as mayflies. Other common names for the winged stages are shadfly, dayfly, fishfly, and drake. The aquatic immature stage, called a nymph or naiad, is widely distributed in freshwater; a few species can tolerate the brackish water of marine estuaries. (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica Online)

[ Back ]

A section of Beaufort's Bay Street from the waterfront, the steeple of St. Helena's Church to the right of center.  Looking from the Beaufort waterfront across to Lady's Island  Contemporary bridge span from Beaufort to Lady's Island |

drum-fish: Fish of the family Sciaenidae.

The drums are so called because of the deep, reverberating sound

they make, especially when flopping about on a deck or a pier.

The "grunts" or "croaks" are a product of a taut, resonating gas

bladder, strummed by muscles especially developed for such a

function.

[ Back ]

Rhetts and Barnwells: Both

are well-known political and business families of South

Carolina, and the names are associated with the movement toward

secession that began the Civil War. See gravestones and

Secession House in the photgraphs below.

[ Back ]

St. Helena church yard North side, with confederate flag. |

Rhett family stones. The stone on the right reads: In memory of Haskell S. Rhett Born Nov. 10th 1818 Died June 29th 1868 Charity suffereth long and is kind. United States flags in background. |

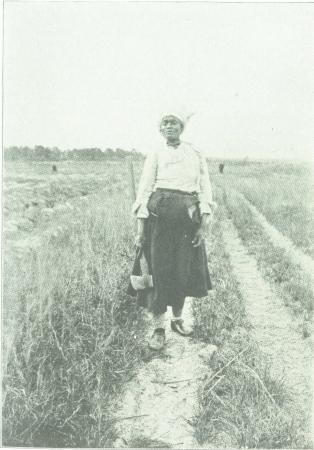

St. Helena Island woman |

pride of India tree: Koelreuteria

paniculata, commonly known now as the "varnish tree." A

flowery deciduous tree which is not native to North American

soil, it produces yellow flowers, particularly in the

summertime. (Source: www.growit.com)

[ Back ]

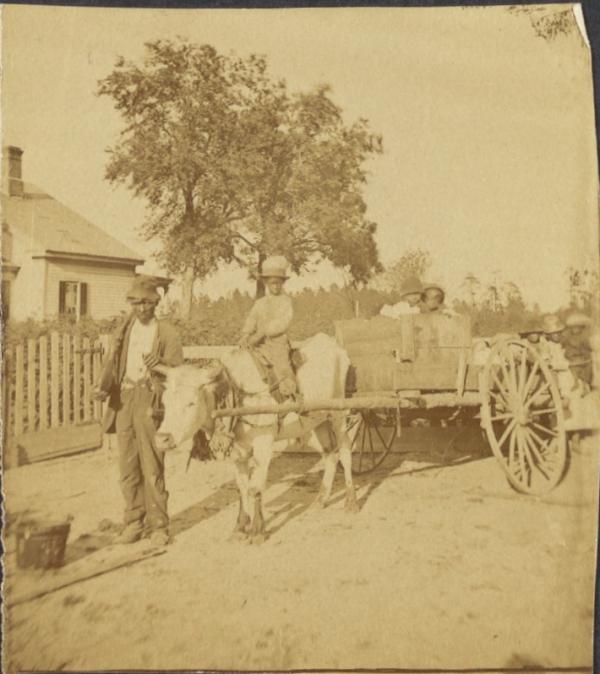

a rickety two-wheeled cart: Such a cart,

pictured below, would have been not only inappropriate but

ridiculous in appearance as transportation for a genteel white

woman. The following image of an "African American man

driving an ox cart, Beaufort, South Carolina, 1904" appears

courtesy of The American Museum of Natural History Research

Library Digital

Special Collections.

Jewett obtained a similar photograph during her March 1888 stay in Aiken, SC, sending it to her sister, Mary.

sassafras switch: The switch

Peter is holding is from a sassafras tree. Most likely, this

variety of sassafras is an American tree of the Laurel family (Sassafras

officinale). The bark is aromatic both in smell and taste,

and may be used for seasoning or flavor in dishes and beverages.

(Source: ARTFL Project: 1913 Webster's Revised Unabridged

Dictionary)

[ Back ]

Good Marsa: "Good Marsa"

refers to Abraham Lincoln "up dere" in Washington, who had sent

the U.S. Navy early in the Civil War to begin the "Port Royal

Experiment," whereby they cleared out all the plantation owners

in the Sea Islands of South Carolina (i.e. forced them off their

property except for their slaves) and conducted what amounted to

a "dress rehearsal for Reconstruction." This is why the old

mistress would not have returned to what had once been her land

until after the war. The "day of the big gun-shoot" was

the Battle of Port Royal on November 7, 1861, an early Union

victory in the war. Wikipedia

says that the battle was so loud that it was reportedly heard

along the coast as far away as present-day Florida. The

battle was fought at some distance from Beaufort, and probably

was louder on St. Helena's Island. It was fought from the

sea against two forts, one on Hilton Head, the other on Phillips

Island, at the Port Royal Entrance on the Towne map above.

(Research assistance: Betty Jean Steinshouer).

An unresolved question about this story is

whether Jewett drew upon local Gullah speakers for her use of

Freedman's dialect. This may be the first story in which

Jewett presents African Americans using dialect speech.

Did she imitate African-American dialect from other works she

had read, such as Uncle Tom's Cabin, or did she listen

to local speakers?

[ Back ]

Port Royal: Port Royal, in

Beaufort County, South Carolina, was considered a key Southern

port during the Civil War, which is why the Union Navy moved

quickly to blockade and then capture it. Wikipedia says:

"In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was first read at

Christmas under the Proclamation tree in Port Royal."

[ Back ]

The "Brick" Church is the only

building remaining at the

Penn Center today that was standing when Jewett visited in 1888.  Bay Street Home One of the antebellum houses on Bay Street in Beaufort, facing southward toward Ladys Island. |

An example of high house with airy balconies and colonnades is this house, near St. Helena's Church, known as the "Secession House." The sign reads: "Edmund Rhett, along with his brother Robert Barnwell Rhett (1800-1876), lawyer, state representative, state attorney general, U.S. congressman and senator, was an outspoken champion of states rights and Southern nationalism from the 1830s to the Civil War. This house, long known as 'Secession House,' was the scene of many informal discussions and formal meetings during the 1850s by the Rhetts and their allies advocating Secession and southern independence."  Hunting Island landscape with oyster beds. |

birthright of the children of Adam:

To labor for one's food. See Genesis 3:17-18.

[ Back ]

the block: the auction block, at

which slaves were traded before the Civil War.

[ Back ]

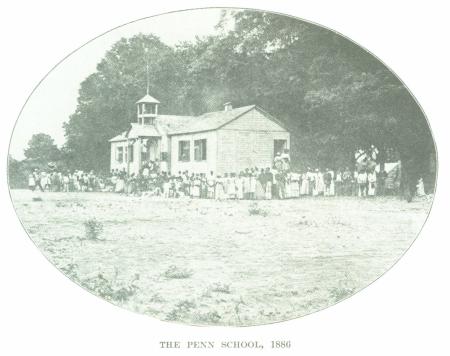

good ladies f'om de Norf: The good ladies were teachers sent in soon after the Union captured St. Helena to educate the former slaves. Wikipedia says: "Slaves were liberated and immediate steps were taken to help improve their lot. One of the most important was the establishment of Penn School to educate them." Now the Penn Center, founded in 1862, it is located south of Frogmore on St. Helena Island. Among the "good ladies," was Laura M. Towne.

Jewett wrote to her sister Mary on April 1 (Easter), 1888:

I feel as if I were at the end of the earth, but I only hope that all the other ends are as pleasant! We came across the long ferry in a rowboat this morning and then drove across Lady's Island and three miles, and across St. Helena's seven miles* before we came to the great clump of live oaks and the old plantation house* where Miss Towne and Miss Murray have lived for over twenty years. They have done everything for the colored people in teaching them other things besides book learning or rather they have taught to find the application of book learning to every day life. You would be surprised to see how neat and nice their houses are – and they were all out working on the land this morning as we drove along and were so respectable looking and polite – Miss Towne has a fortune which has helped her in many ways but nobody can tell how many sacrifices must be made when anybody starts out to do a thing like this and sticks to it – Miss Murray is an Englishwoman and they are such an interesting pair – and way off here they keep account of what is going on in the world and read and think about things as if they were in the middle of them, and perhaps more than we do. All the way along we have been seeing palms and palmettos and strange trees and flowers – and you have no idea what a difference there is in the size of the Sea Island cotton plants from those in Aiken. On some of these islands the cotton was worth $200 a pound (to put with silk) when the common cotton was only five cents.

Ellen Murray (1834-1908), Towne's close friend, shared the work at Penn School from 1862 until her death, primarily as teacher and school administrator. In South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times, Ronald E. Butchart's "Laura Towne and Ellen Murray" (pp. 12-30) says that Murray was born in St. John, New Brunswick, Canada, and though her father died when she was 2, she and her two sisters were educated in Europe and eventually came to live in a substantial home in Newport, RI. There she became a teacher. Invited by Towne to help with the Penn School, Murray became an ardent abolitionist and advocate for African Americans.

Though both Towne and Murray came from privileged backgrounds and were well-educated, Butchart does not confirm that either was independently wealthy, as Jewett suggests in her letter.

Day ob judgment: see Revelations

20:11-14.

[ Back ]

two hunderd poun': the weight in

cotton Sibyl apparently was expected to pick each day during the

cotton harvest.

[ Back ]

wide ribber o' Jordan:

African-American spirituals frequently referred to the River of

Jordan as the boundary between life and death and also as the

boundary between slavery and freedom. In the story of the

Israelites' exodus from Egypt to Israel, the Jordan River

represented the final boundary before they entered the Promised

Land.

[ Back ]

Charleston: Charleston, South

Carolina is a major port on the Atlantic coast and a historic

center of Southern culture. The city is situated on a peninsula

between the estuaries of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, facing a

fine deepwater harbor. The settlement was founded in 1670, and

moved to its present site in 1680.

[ Back ]

|

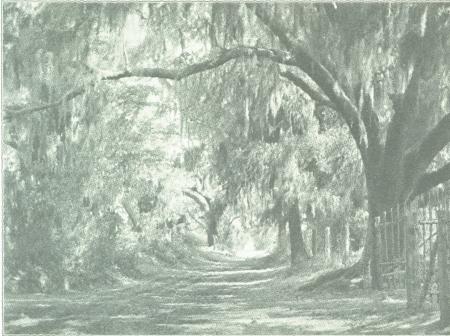

Road to Penn School |

Live oak avenue near Penn School, St. Helena's Island. |

|

|

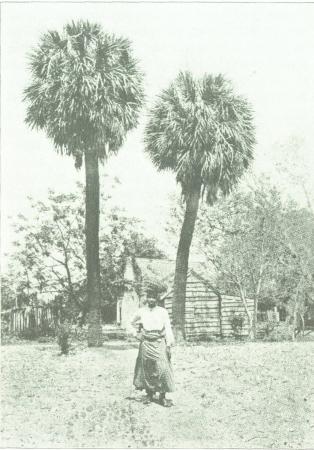

St. Helena Island scene |

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller and Chris Butler, Coe College, with assistance from Betty Jean Steinshouer, Bob Barrett, and various staff and collections at St. Helena's Parish, Penn Center Museum, Beaufort History Museum, and Verdier House Museum in Beaufort, SC.