Extended Notes on Characters in The Tory Lover

Cæsar - Slaves in colonial South

Berwick.

In "The Old Town of Berwick," Jewett

remembers the arrangement of a church that included places for

slaves: "I remember that the unpainted woodwork had taken a

beautiful brown tint with age, and that it used to be a vast

pleasure in my childhood to steal into the silent place, and to

sit alone, or with small, whispering friends, in one of the

high, square pews. The arrangement of the pews and benches

reminded one of the time when there was such careful attention

paid to social precedence, and provision made for the colored

people, of whom there were formerly a large number in Berwick,

and many of them have been excellent citizens. Most of the

prominent families in this part of New England, near tide water,

possessed one or more African slaves in the last century; and

one may still hear delightful stories of their strange traits of

inheritance and their loyal affection to the families which they

adopted as their own, and were always ready to champion. A

little sandy hill, just below the Landing, and above the old

river path that leads to Leigh's, now Yeaton's mills, still

bears the name of Cato's Hill, from the fact that the sunny sand

bank near the top was the favorite retreat of an ancient member

of the household of Gen. Lord (see below). Cato was a native

Guineaman, and the last generation loved to recall the tradition

of his droll ways and speeches."

Also in local church records Negroes,

slaves, and servants known by first name only are baptized and

accepted into membership, but none are recorded that correspond

to slaves or servants mentioned in The Tory Lover,

except for Cato Lord.

See also, "Black

Sara."

[ Top of Page ]

From Chadbourne family genealogy:

JUDGE BENJAMIN 5 CHADBOURNE (41. William 4 Humphrey 3-2 William 1), born Berwick 23 July 1718; baptized 15 Feb 1718/9; died Berwick 16 Mar 1799, age 82 (Young's Index, 4); married first Berwick 21 July 1742 (BVR, 113) SARAH HEARD, baptized Berwick 17 June 1722 (BVR, 212), died 23 Nov 1750 (ibid, 212), daughter of James 4 (Capt John 3 Ens James 2 John 1) and Mary (Roberts) Heard (BVR, 212); married second 10 Oct 1751 (BVR, 113) MARY CHESLEY, daughter of Jonathan and Mary (Weeks) Chesley of Durham NH BVR, 212; Leonard Weeks and Family of Greenland NH). He was commonly referred to as "Judge Benjamin."William Williamson in The History of the State of Maine writes of Benjamin Chadbourne (sometimes spelled "Chadbourn"): "Mr. Chadbourn represented Berwick, his native town, 16 years in the General Court. He was elected into the Council, for Sagadahock, in 1774, and for Maine the two succeeding years. He was likewise a member of the Executive Council several years under the Constitution [of the Commonwealth, after 1780]; and a Judge of the Common Pleas. He was the great grandson of Humphrey Chadbourn, who came and settled at Newichawannock in 1636; and it is believed, his father, of the same name, was a member from Berwick several years in the General Court" (v. 2, ch. 17).

Benjamin probably served as captain in Col Jonathan Bagley's regiment at Louisburg 1745 and with Col Nathaniel Sparhawk in 1762 (American Officers in French and Indian War, NEHGS). He was called Colonel as well as Judge, was an attorney and counselor at law, a colonel in the militia, and a judge of the Court of Common Pleas. He was representative from Berwick for fifteen years from 1756 to 1771, elected by the legislature to serve as Senator to the Massachusetts Legislature from York Co in 1780 (H-Saco & Biddeford, 290). He was a member of the Governor's Council and one of the founders of Berwick Academy, established in

1791. For the Academy he gave ten acres of land in the finest possible situation, and a sum of money besides, to begin the subscription.

Judge Benjamin had purchased much of his brothers' and sisters' share of the family homestead and, therefore, owned much of the original acreage along the Salmon Falls River. In 1761 he purchased from his uncle Humphrey land in S Berwick. He lived there, in a humbler house built after 1720 at 30 Liberty St, [page 84]courtesy of Howard Kaepplein [page 86] while building his mansion house at Liberty and Vine Sts. In a letter dated 26 June 1768, Mary Chesley was admitted from Durham to South Berwick church (Libby's handwritten note in copy of Old Berwick).

Benjamin raised a new house and barn 12 June 1770. In addition to his Berwick properties, he received liberal grants of land in Lebanon. He wrote about 1791 that "no house stands between here and Canada not built within my memory" (probably due to Indian attacks).

Rev John Lord, in his historical address on Berwick Academy, refers to Judge Chadbourn as:

"a veritable patrician, with a great landed estate which his ancestors purchased from the Indians. He lived in a fine colonial residence, surrounded by noble elms. He sent John Hancock a large number of elms from his Berwick estate, to be planted on Boston Common, where some still exist."

Sarah Orne Jewett has made Judge Chadbourn one of the characters of her historical romance The Tory Lover, picturing him as an "old man of singular dignity and kindliness of look." These biographical details are from William M Emery's Chadbourne-Chadbourn Genealogy. The 1790 Census lists 2 males over 16, none under 16, and 2 females in Benjamin's household.

In "The Old Town of Berwick," Jewett writes: "I shall take the liberty of quoting from the historical address given at the celebration of the academy's hundredth year, by Rev. John Lord, LL. D., one of the most gifted and best known pupils of the old hill school.

'The founders,' says Dr. Lord, 'were all honorable men, at least they were all respectable citizens in this prominent village, or were distinguished clergymen or lawyers in the neighboring towns. Primus inter pares, there was old Judge Benjamin Chadbourne, a veritable patrician, with a great landed estate, which his ancestor purchased from the Indians." Here we find the great-grandson of that Humphrey Chadbourne who came with the earliest settlers, and was for many years their leader. The late President Chadbourne of Williams College belonged to a later generation of the same family. "Judge Chadbourne lived in a fine colonial residence surrounded by noble elms, not far from the Vineyard, and was a great lover of trees. He gave to his friend, John Hancock, a large number of elms from his Berwick estate to be planted on Boston Common, where some of them still exist.'

[ Top of Page ]

Duke and Duchess of Chartres

(23, 39): Louis Philippe Joseph (1747-1793) was Duke of Chartres

and then Duc d'Orléans, a French nobleman, cousin of King Louis

XVI.

According to Encarta Encyclopedia,

during the French Revolution, he "adopted the name Philippe

Égalité. Before the Revolution, he distributed books and papers

throughout France advocating liberal ideas. In June 1789, during

the meeting of the Estates-General summoned by the king, he led

the 47 nobles who seceded from their own order to join the

revolutionary third estate. He was elected to the National

Convention and voted for the death of Louis XVI. In 1793, during

the Reign of Terror, he was guillotined. His son Louis Philippe

became king of France in 1830.

In Paul Jones, Buell identifies

him as "the Sailor Prince," and says that he was "selected in

1774 to succeed the Duke de Bourbon-Penthievre in the office of

High Admiral of France.... He had a few years before married

Mary Adelaide de Bourbon-Penthievre, daughter of the High

Admiral. She was one of the most beautiful and accomplished

women of her time; granddaughter of the Count de Toulouse, High

Admiral of France at the beginning of the Eighteenth Century,

Commander of the French fleet in the great battle of Malaga in

1704.... The Count de Toulouse was a son of Louis XIV. by Madame

de Montespan ...." (1;25-6). S. E. Morison and Evan Thomas

generally corroborate this account. Morison identifies the

Duke's father-in-law as Grand Admiral of France (173). Evan

Thomas notes that the duke was "Grand Master of all the Masonic

lodges in France," an important connection between him and John

Paul Jones (142).

Jewett says the Duchess of Chartres was

Jones's "good angel" in France (Chapter 39). Thomas suggests

that Jones's relationship with the Duchess was quite limited

(145).

[ Top of Page ]

Judge Curwen (38): Samuel

Curwen (1715-1802) was American-born and a judge of Admiralty in

the British colonial administration of the American colonies, a

loyalist with a complex attitude toward his homeland, and an

American refugee in England from 1775-1784. Journal and

Letters of the Late Samuel Curwen (1842) -- edited by

George Atkinson Ward (1793-1864) -- indicates the complexity of

the positions of some loyalists. On the title page of his book

appears this quotation from 1780: "For my native country I feel

a filial fondness; her foibles I lament, her misfortunes I pity;

her good I ardently wish, and to be restored to her embraces is

the warmest of my desires."

During his period as a refugee in

England, he traveled widely, recording his impressions in his

journal. These, along with his letters, offer a good glimpse of

the thoughts and feelings of a principled Tory and of the

difficulties such refugees faced. Following is a sample letter

of June 1776 to Charles Russell.

TO DR. CHARLES RUSSELL, ANTIGUA.

London, June 10, 1776.DEAR SIR:

I congratulate you on your retreat from the land of oppression and tyranny; for surely, greater never appeared since the days of Nimrod. I sincerely wish well to my native country, and am of opinion that the happiness of it depends on restraining the violences and outrages of profligate and unprincipled men, who run riot against all the laws of justice, truth and religion. Sad and deplorable is the condition of those few that like Abdiel, amidst hostile bands of fallen spirits, retain their primitive loyalty. So strangely unprosperous hitherto have been the measures of administration in America, that the active provincials have taken courage, and accomplished what in contemplation would have appeared morally impossible. Gen. Burgoyne sailed from hence ten weeks ago for Canada with four thousand Brunswickers and seven or eight regiments; Lord Howe in the Eagle about a month, and the first division of Hessians, consisting of eight or ten thousand, about a fortnight before him. Gen. Howe, his brother, with nine thousand was at Halifax the beginning of April. The second division, ('tis said,) will sail this week, consisting of four thousand, which completes the whole number of foreign troops. The whole of the regular army on the continent will not be short of forty thousand men. It is surprising what little seeming effect the loss of American orders has on the manufactories; they have been in full employ ever since the dispute arose; stocks are not one jot lessened, the people in general little moved by it; business and amusements so totally engross all ranks and orders here that administration finds no difficulty on that score to pursue their plans. The general disapprobation of that folly of independence which America now evidently aims at, makes it a difficult part for her friends to act.

By letters from Salem to the 16th April I find they were in a quiet state there, and hugging themselves in the fatal error that government had abandoned the design of reducing them to obedience. Six vessels laden with refugees are arrived from Halifax, amongst whom are R. Lechmere, I. Vassal, Col. Oliver, Treasurer Gray, etc. Those who bring property here may do well enough, but for those who expect reimbursement for losses, or a supply for present support, will find to their cost the hand of charity very cold ; the latter may be kept from starving, and beyond that their hopes are vain. "Blessed is he (saith Pope) that expecteth nothing, for he shall never be disappointed;" nor a more interesting truth was ever uttered.

I find my finances so visibly lessening, that I wish I could remove from this expensive country, (being heartily tired of it,) and old as I am, would gladly enter into a business connection anywhere consistently with decency and integrity, which I would fain preserve. The use of the property I left behind me I fear I shall never be the better for; little did I expect from affluence to be reduced to such rigid economy as prudence now exacts. To beg is a meanness I wish never to be reduced to, and to starve is stupid; one comfort, as I am fast declining into the vale of life, my miseries cannot probably be of long continuance.

With great esteem, etc.

S. CURWEN.

Mr. & Mrs. John Davis of

Bristol, England (32):

It is not clear to what degree this

couple is based on historical persons. Graham Frater's

research in Bristol provides this information: Responding to the

suggestion that John Davis might have been based on an

historical figure, Sheila Lang of the Bristol Records Office

writes 'I have found references, including letters, relating to

a Captain John Davis who was voyaging to Barbados in 1723, in a

Bristol Record Society publication: The Trade of Bristol in

the 18th Century, edited by W. E Minchinton, (BRS Vol 20).

There is no John Davis in our lists of Aldermen of the city for

the 18th century.'

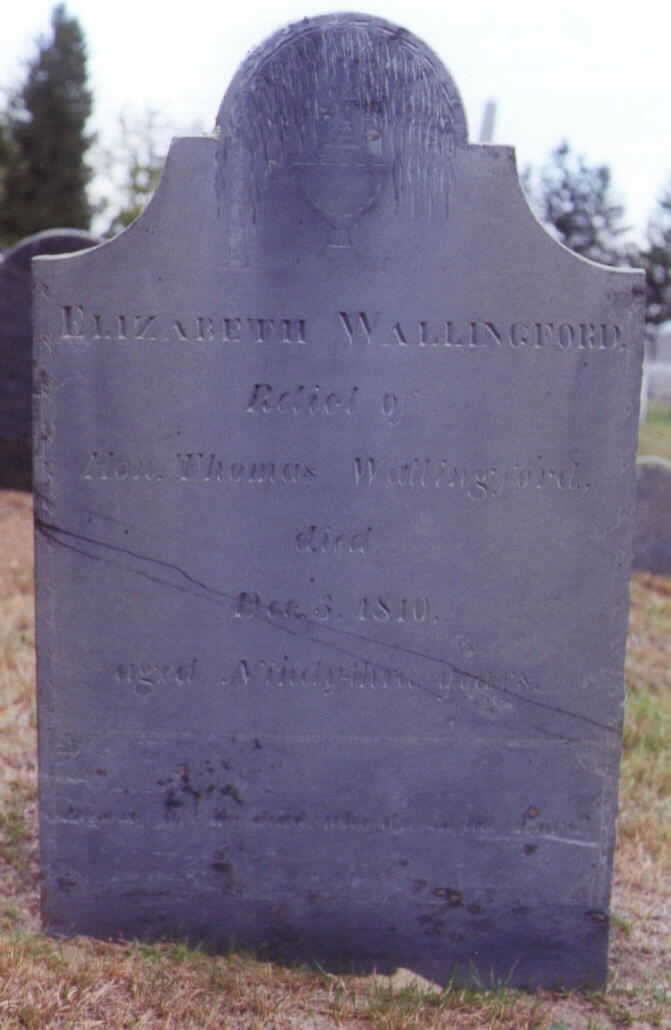

In Chapter 32, Jewett establishes a

series of relationships that are complicated and that tie Mrs.

Davis, Mary Hamilton and Madam Wallingford together in a common

ancestry with one of the great heroines of the Piscataqua

settlement, Hetty Goodwin, whose story is given in Jewett's

version, in the entry on Hetty Goodwin. Mrs. Goodwin's captivity

story is itself complicated, and much might be said about what

it means to connect Mary and Madam Wallingford with Hetty.

Jewett indicates that Mrs. Davis is the

youngest daughter of Hetty Goodwin and is kin to Mary's own

people as well as to the Wallingfords. This daughter of Hetty

has married the son of a wealthy Bristol merchant, older than

she, who is called "Sir" in Chapter 33 and who is an alderman.

He is supercargo of the beautiful ship, The Rose and Crown,

when he meets and courts his wife. He promises her that she will

visit home every other year -- because she is so attached to her

mother -- but fails to keep this promise. What basis is there in

fact for these characters and their relationships?

The Wallingford - Hetty Goodwin Connection

This is quite complicated. The

Chadbourne family web site provides this sketch of Mehitable and

Thomas Goodwin's family (I have put some key parts in boldface):

http://www.chadbourne.org/Gen4.htmlWe can note that none of Hetty's daughters married John Davis of Bristol, though some people thought Mary married a John Davis. And we see, of course, that Hetty's youngest son married into the Wallingford family. According to the Wallingford family web site, the children of Judge Thomas Wallingford (see below) by his first wife, Margaret Clements, were:20. THOMAS C4 GOODWIN SR (5. Margaret C3 Spencer, Patience 2 William 1), born Berwick circa 1657; died before administration of his estate was granted to widow Mehitable 26 Mar 1714 (MPA 2/141,188, 3/64); married 1685 MEHITABLE PLAISTED, born 1670, died after 2 June 1740 (YD), daughter of Roger and Olive (Coleman) Plaisted.

He and his wife and infant son were captured by Indians at William Love's Inn at Salmon Falls ME.

"Thomas and Mehitable were separated after capture and each believed the other dead; indeed a local tradition says that "Hetty" took to herself a new husband in Canada and left him when she learned that Thomas was living. This seems doubtful, as no record of the marriage has been found. Mehitable's story has been printed in the Magnalia and elsewhere.

She had a cruel captor who was disturbed by the wailing of her young baby. To quiet the child she would sit for hours in the snow far from the fire, but the Indian, impatient of her slow progress, snatched it from her arms and killed it.

Three years later, at Montreal, on Monday, 11 May, 1693, there was solemnly baptized an English woman, called in her own country, Mehetabel and by the French, who captured her in war 18 March 1690, Esther, who, born at Barwic, in New England 30 April (old style or 19 May new style) 1670, of the marriage of Roger Pleisted, Protestant, and of Olive Colman, of the same religion, and married to Thomas Gouden, also Protestant, living since nearly three years in the service of Mademoiselle de Nauguiere. She was named Marie Esther... "

(Coleman, New England Captives Carried to Canada I:185-186)."Hitobl Goodin" was one of those redeemed in Oct 1695 by Mathew Cary (ibid, I:74). She and Thomas settled at Old Fields, S Berwick. In Feb 1726, widow Mehitable sold land in Berwick which had been sold to Daniel Goodwin in 1674 from Moses Spencer (YD). Her handmade gravestone is in the Old Fields burying ground in Berwick (Coleman I:186).

Children, surname GOODWIN:

i. son C5, killed by Indians 1690 (Cotton Mather: Magnalia Christie Americana).

ii. THOMAS JR, b Kittery 29 July 1697 (KVR, 11); living Oct 1755; m 2 Dec 1722 ELIZABETH BUTLER, b & bpt Berwick 22 Sep 1699, dau of Thomas and Elizabeth (Abbott) Butler and niece of Sarah Abbott who m Thomas Wills (LND, 57-8). Children, surname Goodwin: 1. Elisha, bpt S Berwick 9 Oct 1726, m Sarah _____, at Blueberry Hill, 10 ch. 2. Thomas, bpt 9 Oct 1726, m1 Mary Hicks, m2 Eunice Lord. 3. Olive, bpt 26 July 1728, m 19 Dec 1745 S Berwick Nathan Lord Jr, 4 ch. 4. Moses, bpt 27 Oct 1728, d 1766, unm. 5. Elizabeth, bpt 9 Aug 1730 or 6 Sep 1730, m1 29 Mar 1752 Alexander Shapleigh who d 1762, she m2 Samuel Jenness of Rye NH, 4 ch. 6. Mary, bpt 15 Apr 1733, d 18 July 1736. 7. James, b 17 Mar 1735, d 18 July 1736. 8. Capt James, bpt 15 May 1737, m Sarah Griffith. 9. Mollie, bpt 25 Jan 1740, unm 1766.

iii. ICHABOD, b Kittery 1 June 1700 (KVR, 11); d 27 Oct 1777 (Master Tate's Diary); m 25 Aug 1729 ELIZABETH SCAMMON, d 8 Feb 1774 (NH Gazette, 60), dau of Capt Humphrey of Saco. He was a blacksmith of Berwick 1728/9. 10 children, surname Goodwin: 1. Hannah, b 24 July 1730, m 23 Nov 1749 Tristram Jordan who d 1821, age 90, 3 ch. 2. Ichabod, b 17 Aug 1732, d 1732. 3. Humphrey, b 24 Dec 1735, d 26 Aug 1736. 4. Mary, b 24 Jan 1736/7, d 16 Apr 1774, age 37 (NH Gazette, 60), m1 Blackberry Hill, Berwick, Foxwell Curtis Cutts, son of Richard Cutts, m2 S Berwick

1762 Rev John Fairfield, son of William Fairfield, 5 ch. 5. Ichabod, b & d 1739. 6. Dominicus, b 24 Apr 1741, m1 Hannah Hill, d Berwick 10 Mar 1772 (Master Tate's Diary, 183); m2 Elizabeth (Littlefield) Perkins. 7. Ichabod, b 14 May 1743, m Mary Wallingford. 8. Samuel, b 17 Aug 1745, unm. 9. Elizabeth, b 25 Dec 1748, unm. 10. Sally, b 21 Apr 1754, m1 S Berwick 24 Apr 1772 Temple Hight, son of William Hight, m2 Rishworth Jordan, son of Judge Rishworth Jordan, 5 ch.iv. MEHITABLE, b ca 1702; d 1761 (GDMNH); m before 1758 THOMAS BUTLER, b Berwick 6 Mar 1698 (KVR, 17), d between 12 Feb 1759 (date of will) and 4 Apr 1759 (date of proving; MW 864-5), son of Thomas and Elizabeth (Abbott) Butler (KVR, 17). They lived in Portsmouth. She is probably the Bial who owned the covenant on 20 May 1716, name shortened by Rev Wise. Children, named in father's will, surname Butler: 1. Moses. 2. Thomas. 3. Olive. 4. Elizabeth. 5. Mary. 6. Samuel. 7. (LND, 124, says 7 children).

v. OLIVE, bpt Berwick 14 Mar 1707/8 (NEHGR 82[1928]:75); d 12 May 1772 (LND, 188) or 10 June 1774 (Master Tate's Diary, 189); m by 1758 TIMOTHY DAVIS of Berwick, bpt 25 Dec 1715, d 10 June 1774 (ibid), possibly son of James and Susanna. Child, surname Davis: 1. perhaps Timothy who m Margaret _____ and had children bpt at 1st Congregational Church of Biddeford in the 1750s (MHGR VI & VII).

vi. MARY, b 1708, bpt 18 June 1710; m1 Portsmouth 1729 RICHARD LORD JR, b ca 1708, d ca 1735 (MPA 16/241, 275, 473), son of Capt Richard and Mary (Goodwin) Lord (The supposed marriage to John Davis as reported in NEHGR 25:395 is incorrect); m2 ca 1740 (KVR, 13, MPA 16/241,275,473) JOHN COOPER JR, b 7 Oct 1702, d 1792. Children, surname Lord: 1. Daniel, dy. 2. Richard, dy. 3. Olive, m 25 Aug 1750 Jonathan Abbott Jr (MPA 9/54, 12/376), son of Jonathan and Bathsheba (Brackett) Abbott. Children, surname Cooper: 4. Sarah, bpt 14 Feb 1741/2. 5. Alexander, bpt 18 Aug 1745, m 31 Dec 1756 Patience Goodwin. 6. Mary, bpt 21 Mar 1746/7, m 27 Nov 1765 Moses Warren, son of James. 7. Daniel, bpt 25 May 1749, m 2 Dec 1773 Mary Warren, dau of William. 8. John.

vii. JAMES, m MARGARET WALLINGFORD; both alive 1756. Children, surname Goodwin: 1. Margaret, bpt Berwick 27 Feb 1741/2, m 30 Oct 1763 Thomas Hodgdon Jr, bpt 10 June 1739, will Apr 1810, resided Cranberry Meadow, 5 ch. 2. Mehitable, b Berwick 24 Apr 1744, m 22 Oct 1767 Thomas Chadbourne, b 30 Apr 1743, son of Joseph (see Thomas for 5 ch). 3. Major Jedediah, bpt 18 May 1746, m Hannah Emery. 4. Olive, bpt 28 May 1749, m S Berwick 19 Mar 1770 (BVR) Nehemiah Gray, lived in Coxhall/Lyman, bur Elder Grey Cem, N Waterborough, at least 1 ch. 5. Mary, bpt 4 Feb 1753, m Somersworth 1 Apr 1772 (Master Tate's Diary) Dr Ebenezer Hall. 6. Silas, bpt 8 June 1760, m1 Isabella Bragdon, m2 Anna Clements. 7. Amos Wallingford, bpt 13 Apr 1755, m Eunice Getchell. 8. Thomas, b 14 Jan 1763, m Anna Goodwin. 9. James, taken prisoner in Revolution and d in Halifax prison. 10. Silas, taken prisoner in Revolution and d in Halifax prison.

Hannah born 5 May 1720Though this has not been established beyond doubt, it appears that James, the son of Hetty Goodwin married Margaret, the daughter of Thomas Wallingford by his first wife. Their dates correspond well, and despite appearances, they lived close to each other and were children of powerful and important members of the community. This would make Madam Wallingford kin -- though seemingly fairly distant -- to Hetty Goodwin, in that Madam Wallingford's step-daughter marries Hetty Goodwin's son.

Judith born 25 Mar 1722 Dover, Strafford County, New Hampshire

Ebenezer born 21 Jul 1724 died 15 May 1777

Margaret

Abigail born 30 Sep 1726 Dover, Strafford County, New Hampshire

Rachel.

Furthermore, according to the Wallingford family web site, General Ichabod Goodwin (grandson of Hetty through her son, Ichabod) also married into the Wallingford family (Molly) in 1768. Molly/Mary was a granddaughter of Judge Thomas Wallingford, the daughter of Captain Thomas Wallingford (the judge's son by his second wife, Mary Pray). This Mary/Molly was Madam Wallingford's step-granddaughter.

Where John Davis of Bristol comes in

The Goodwin family web site lists the

children of James Goodwin (c. 1658 - 1697), half-brother of

Thomas Goodwin (husband of Hetty). James married Sarah Thompson

(1652-1714) in 1686. Their fourth child is:

MARY, (niece of Thomas & Hetty) b 23 May 1691; d between 11 Mar 1756 when she wrote her will and 5 Apr 1763 when Joseph Lord admin it (MPA 11/101); m (NEHGR 25:395) JOHN DAVIS or m ca 1707 (YD 37:225-6) Capt RICHARD LORD, b Kittery 1 Mar 1684/5 (KVR, 29), d before 21 May 1754 when admin granted to Mary (MPA 7/27, 9/229), son of Nathan and Martha (Tozier) Lord of Berwick (LND). Mary may have married second John Davis (LND, Barry Goodwin). Children (MPA 9/53, 11/101), surname Lord: 1. Richard, b 1708, m Mary Lord (#20.vi). 2. Annah, m _____ Shackley. 3. Keziah, m _____ Nason. 4. James. 5. Aaron. 6. Joseph. 7. Jabez.The condition of this list indicates that this family is not well-represented in the records; hence this site is not very sure about Mary's marriage to John Davis. But if the site's guess is correct, then a niece of Hetty Goodwin -- rather than a daughter -- seems to have been married to John Davis, either as a first or last marriage, or perhaps both. Another genealogy web site http://www.weymouthtech.com/Genealogy/ps35/ps35_065.htm) adds the following information:

The NEHGR, Vol. 23 or 24, says "John Davis, of Bristol in Great Brittaine, and Mary Gooding, of Neckswamick, were married 23rd of October, 1718."The author of this web site is persuaded that this Mary Gooding is in fact, James Goodwin's daughter, Mary, and therefore, a niece of Hetty Goodwin. "Neckswamick" or Newickawanock was an earlier name of South Berwick. While this is murky, especially when considering the dates of Mary's marriages and death, and does not square exactly with Madam Wallingford's account of Mrs. Davis's parentage, it is remarkably close. It would make sense for Jewett to possess a version of this story because of her friendship with Madam Wallingford's granddaughter, Mary Cushing Hobbs, daughter of Olive Wallingford Cushing, who was Madam Wallingford's daughter. A glimpse of this friendship appears in "The Old Town of Berwick."

This information makes it probably impossible to determine whether Jewett was fictionalizing identities and relationships she was aware of or reconstructing them from what her friend gave her as oral history and family lore.

Mary Hamilton's kinship with Hetty Goodwin, Madam

Wallingford, and Mrs. Davis

Keeping in mind that we are to

see Mary as Jonathan's sister, this is simpler than discovering

Mrs. Davis's historical model, but still it has its

complications. There are several Hodsden, Hamilton and Goodwin

genealogical web sites available on the Internet; these and

other sources agree that Goodwins and Hamiltons intermarried in

the 18th Century, but they don't exactly agree on who married

whom.

To summarize, Hetty Goodwin's

brother-in-law was Daniel Goodwin. His daughter married a

Hodsdon, and their daughter, Abigail Hodsdon married either Bial

or Abiel Hamilton (See Jonathan Hamilton's entry below). Sources

seem to agree that Abigail Hodsdon was Jonathan's (and so in the

novel, Mary's) grandmother, though his grandfather's identity is

unclear. In either case, Mary's grandmother probably was Hetty

Goodwin's grand niece.

There is a bit more, as well. Everett

Stackpole in Old Kittery and Her Families (1903) says

that Margaret Hodsdon (Abigail's youngest sister) married

Gabriel Hamilton, Bial's younger brother (489). If this is

correct, then there is another small connection between Jonathan

Hamilton and Hetty Goodwin, his uncle having married one of her

grand nieces.

A Sarah Orne Jewett Connection

This is not quite the whole story of

the connections between Mary Hamilton, Mrs. Davis, Mary

Wallingford, and the historical matriarch and heroine, Hetty

Goodwin. We need to keep in mind that for Jewett's purposes in

this novel, a "step-relationship" seems as weighty as a "blood"

relationship, as we see in tracing how Elizabeth Wallingford is

related to Hetty Goodwin.

By a similar relationship, Jewett

herself is related to Jonathan Hamilton, and so to her fictional

Mary, Jonathan's sister, and the historical Mary, Jonathan's

wife. Jonathan's second wife was Charlotte Swett of Exeter (See

Jonathan Hamilton's entry below). After his death, Charlotte

married Governor John Taylor Gilman of Exeter, a great uncle of

Mrs. Theodore Jewett (Sarah's mother).

[ Top of Page ]

General Goodwin:

In Chapter 2, he laments the decline of

law and order, referring to slavers, the minister guesses, and

so leading Jones to raise an issue over which the community is

divided. In Chapter 29, he leads in breaking up the mob that

attacks Mrs. Wallingford.

This is General Ichabod Goodwin

(1743-1829) of Old Fields, grandson of Hetty Goodwin, according

to Jewett in "The Old Town of Berwick"; she also reports that he

was the father of Ichabod Goodwin who became governor of New

Hampshire. At the beginning of the Revolution, the elder Mr.

Goodwin served in the Provincial Congresses of 1775. Williamson

reports in The History of the State of Maine that

Goodwin was put in charge of one of the state's two divisions of

militia in 1783 at the rank of Major-General. (v. 2, ch. 18). It

would appear, therefore, that he did not receive the title of

"general" until after the Revolutionary War. This has not been

verified, however, and further information is welcome.

This anecdotal legend of General

Goodwin is reported in Maine: A Guide 'Down East' by the

Federal Writers' Project (1937):

At one time a band of thieves lived in the near-by Negutaquit Woods. A favorite local folktale tells how the General left for church one Sunday morning with an admonition to his small daughter, who was remaining at home with a servant, to be courteous to any guests who might arrive during his absence. Shortly after his departure, the thieves approached, and the child, unaware of their identity and mindful of her father's orders, importantly assumed her rôle as hostess and asked the maid to prepare food for them. The visitors accepted the hospitality without comment, eating their fill; then they began to collect the family silver and other valuables, packing them in bundles. The child was puzzled and frightened, torn between a suspicion that something was wrong and a fear of violating the laws of hospitality; after she had seen one treasured object after another snatched up, she came forward timidly, offering her own silver cup as a substitute for her mother's possessions. The leader stared at her, abruptly told his men to leave the bundles and led them away. The story is that sometime afterward, when the thieves had at last been jailed, the General, in talking with them, asked the leader why he had failed to take anything of value from the Goodwin home; the answer, according to the old wives, was that he could not do it after the little one had treated him 'for the first time in his life like a gentleman.' (337-8).According to the Wallingford family web site, Goodwin married into the Wallingford family (Molly) in 1768. Molly was a daughter of Captain Thomas Wallingford (son by an earlier marriage) and granddaughter of Colonel Thomas Wallingford.

[ Top of Page ]

Hetty Goodwin (1670-1740): Described

in Chapter 32 as the mother of all the Goodwins and as being a

Plaisted of the Great House. Judge Benjamin Chadbourne's

"History of the Town of Berwick" at the Old Berwick Historical

Society, indicates that the Great House was built by the

Plaisted family, started by Colonel Ichabod Plaisted around the

beginning of the 18th Century. Chadbourne reports that the Great

House was burned in January 1738.

In "The Old Town of Berwick," Jewett

says:

"Among these unfortunate captives was Mrs. Mehetable Goodwin, who may be called the mother of all that representative widely scattered Berwick family, which has shown in different generations so much ability and such marked traits of character. Hetty Goodwin, as she has always been called, was taken by the Indians, with her husband and baby. The man and wife were separated by two parties of the savages, and set forth on their long and suffering journey to Canada, each believing the other to be dead, and leaving behind them their comfortable farm on a beautiful hill above the river, near the Plaisted garrison. In the early part of the march one of the Indians snatched the baby from its mother's arms and dashed its head against a stone; and when the poor mother dragged her weary steps behind the rest and could not still her cries, they threatened if she did not stop weeping to kill her in the same way. At nightfall she was stooping over a brook trying to wash a bloody handkerchief, and her tears were falling fast again. She forgot the threats of her captives. Suddenly, a compassionate squaw, pitying the poor, lonely mother, threw some water in her face, as if in derision. The tears were hidden, and no one else had noticed them. "This squaw had a mother's heart," the old people used to say, in telling me the story. In Canada the captives underwent great hardships, and "Hetty Goodwin, a well-off woman," was so hungry that she sometimes stole food from the pigs. She was bought at last by a Frenchman; and, supposing herself to be a widow and despairing of ever reaching home again, she married him and had two children. Their name, corrupted probably from the French, was Rand; and the Portsmouth family of the name is said to be descended from them. As I was once told, the captive husband "was a Goodwin, and smart"; so after a while he outwitted the Indians in some way and gained his liberty; and, coming to his home, found that his wife was still alive. He went back to Canada and found her and brought her back; after which they managed to live unmolested and were the parents of many children. Hetty Goodwin's half-buried little headstone may still be seen in the Old Fields burying ground. I never can look at it without a thrill of feeling, or pass the pleasant place where she lived without remembering that she knew that lovely view over hill and dale, up the river, and must often have dreamed and longed for the sound of the river falls, in the far country to which she was carried a lonely captive, in the northern wilderness of Canada."Marion Rust points out that Jewett drew upon Francis Parkman's Count Frontenac and New France Under Louis XIV (1880), and that this story also was told by Cotton Mather in Decennium Luctuosum: An History of Remarkable Occurences in the Long War....(1699). See Rust, ed. "'The Old Town of Berwick' by Sarah Orne Jewett." New England Quarterly 73:1 (March 2000), 122-158.

Mrs. Mehetable Goodwin's stone in the Old Fields cemetery bears only her name, without dates.

See also: Mr. and Mrs. John Davis.

Problems with Jewett's Version of Hetty Goodwin's Captivity

In all three of the above versions, Jewett relates that after her captors killed her son, they threatened to kill Hetty as well if she would not control her grief. Seeing that she could not keep from weeping, a kindly Indian woman with "a mother's heart" splashed water in her face, creating -- through an apparent act of cruelty -- a rationale for Hetty's tears, and saving her from her captors' wrath. Useful as this story is to Jewett in her two novels, it is unlikely to be true. The multiple accounts we have of Hertel's raid indicate that there were no women among the raiders. The situation differs from captivities in King Philip's war (1675-6), such as that of Mary Rowlandson, when the raiders were exclusively Native Americans with some local camps, through which prisoners could be passed on their route to Canada. Hertel's raiders came from Three Rivers, in Canada, and were made up of French soldiers and an Indian force, mainly Sokoki, who would be familiar with the Salmon Falls area, but not recently residing there. The raiders had to move quickly through rough terrain in the winter. At his website, historian Emerson Baker reprints a transcription of an eye-witness account: “French Captive Examination from Piscataway 19th March 1690” (http://w3.salemstate.edu/~ebaker/chadweb/raiddocs.htm). Failing to mention any women traveling with the raiders, this account confirms the military nature of the raid: "yt they came by ordr of the french Govr at Canada & that both french & Indians are in pay at ten Livers p month."

Though it is not impossible that women accompanied this group, it is unlikely, and there is no mention of Indian women in written accounts from Mather through Parkman to more recent summaries, such as that in Chester B. Price's description of "Historic Indian Trails of New Hampshire" of the Newichwannock-Sokoki trail, which the raiders followed in their escape (reprinted in The Indian Heritage of New Hampshire and Northern New England. McFarland: Jefferson, NC, 2002, pp. 160-162). Colin Calloway's account emphasizes the arduous military character of the raid: " … twenty-four French, twenty to twenty-four Sokokis, and five Algonquins -- led by François Sieur d'Hertel -- left Three Rivers, crossed Lake Memphremagog to the Connecticut River, and, after three months hard traveling, attacked Salmon Falls on the New Hampshire frontier" (The Western Abenaki of Vermont 1600-1800. Norman: U Oklahoma P, 1990, pp. 94-5). A. T. Vaughan and E. W. Clark say that Governor Frontenac, who ordered the raids, had recently lowered the bounty on scalps and raised it on prisoners, thus encouraging the raiders to bring more prisoners to Canada (Puritans among the Indians, 136). In The Captor's Narrative, William H. Foster points out the need for captive labor in the developing French colony.

We may also notice another difference between early accounts of the captivity and more recent accounts of the raid. Mather and Parkman focus on the prisoners, emphasizing that they were "given to the Indians," and as a result suffered special cruelties, such as the killing of children and various tortures. Both, of course, are making cases against the Indians. Mather wishes to persuade readers that Indians are bestial minions of Satan, to be either converted or extirpated from the Christian colonies. Parkman wishes to persuade readers that Indians are a savage race, generally incapable of civilization, and, therefore, those who cannot convert to Protestant Christianity are doomed to extinction by historical forces represented by America's Manifest Destiny. More recent accounts, such as Calloway's, emphasize the conditions of international warfare between France and England, and the military character of this and other raids. It was the French intention to terrorize English colonists on the frontier and drive them out. The British had the same intentions toward the French. Both used Indians in warfare in part because they could do what "civilized" soldiers were not allowed to do, ruthlessly kill prisoners who proved incapable of keeping up with the necessary pace of the raiders as they struck and retreated. Calloway, for example, emphasizes that the Frenchman d'Hertel was in command, while earlier writers, whom Jewett follows, typically name the Indian, Hopehood, as a co-commander.

The second element of Hetty Goodwin's story that probably is legendary appears only in "The Old Town of Berwick," the assertion that Goodwin, believing her first husband dead, remarried while held prisoner in Canada.

In Old Kittery and her Families, Everett Stackpole, doubting the marriage, provides this account:

Other captives were Thomas Goodwin and his wife, who was Mehitable, daughter of Lieut. Roger Plaisted. The husband and wife were assigned to different bands of Indians and so remained apart. After his escape he is said to have returned to Canada for the ransom of his wife. An account of her sufferings was written by Rev. Cotton Mather in his Magnalia, and has been often republished. Her son, about five months old, was barbarously murdered before her eyes and hanged by the neck in a forked bough of a tree. After terrible sufferings from grief, cold and hunger, she arrived at Montreal. The record of her baptism, written in French, has been kindly furnished me by Miss C. Alice Baker, who has published much about the captives taken in the French and Indian Wars. The translation is as follows:Again, it remains possible that Hetty remarried in Canada and perhaps even bore one or more children while there, but the marriage would have had to take place, as Stackpole points out, after May of 1693. C. Alice Baker's inquiry elicited no record of a marriage, and Foster's research for The Captor's Narrative turned up no evidence that Hetty married in Canada. He discusses her as among two married English women who converted to Catholicism during their captivities (144).

"Monday, 11 May, 1693, there was solemnly baptized an English woman called in her own country Mehetabel, and by the French who captured her in war, 18 March 1690, Esther, who was born at Barvic, in New England, 30 April (old style, or 19 May new style) 1670, of the marriage of Roger Pleisted, Protestant, and Olive Coleman of the same religion, and was married to Thomas Gouden [Goodwin] also Protestant. She has lived for about three years in the service of Mademoiselle de Nauguiere [written also de la Naudiere]. She was named Marie Esther. Her godfather was Messire Hector de Catlieres, Chevalier, Governor for the King in the Isle of Montreal and its vicinity. Her godmother was Damoiselle Marguerite Renee Denis, widow of Monsieur Naugiere de la Perade, during his life Captain of the Guard of Monsieur le Conte de Frontenac, Governor of New France. The baptism was performed by M. Francois Dolie de Casson, Grand Vicar of the most Illustrious and most Reverend Monscigncur Bishop of Quebec." (Signed) Chevalier de Catlieres,

Marguerite renee denis,

Fran. Doelier,

E. Guyoth, Cure.I have heard the tradition from one of her descendants that Mehitabel Goodwin was married in Canada to a man named Rand (some say Pain) and that descendants are living in Portsmouth. This is highly improbable. She was baptized in May, 1693, and could not have been married before, and she was ransomed in October, 1695. The Rands of Portsmouth are all, doubtless, descended from the Francis Rand who came over in the company of Capt. John Mason. (Old Kittery and Her Families, 1903, pp. 165-6).

One wonders about how the story of this marriage made it into the oral history of South Berwick and so, into Jewett's account of Hetty in "The Old Town of Berwick." It certainly adds to the pathos of the 5-years separation of the young married couple, but it also adds complications that beg for deeper exploration. How did Hetty feel about leaving her second husband to return with her first? How did her children by the second marriage end up in nearby Portsmouth, NH? What relationships did they sustain with their mother?

Jewett does not mention Hetty's supposed second marriage in either of her novels, probably because it would have seemed inappropriate and would have worked against her reasons for bringing Hetty's story into her narratives. Indeed, in The Tory Lover (Chapter 32), Madam Wallingford emphasizes her ancestor's extreme reticence about her trials, suggesting that Hetty was not herself the witness who provided Cotton Mather with his account of Hetty's captivity. Possibly, C. Alice Baker, Jewett's close friend according to biographer Paula Blanchard (Sarah Orne Jewett, pp. 225-6), told Jewett about the baptism between 1894 and the publication of The Tory Lover in 1901. Baker did not retell Hetty's story in True Stories of New England Captives Carried to Canada During the Old French and Indian Wars (1897), but she may have completed her research on Hetty Goodwin before 1897.

Though this detail seems less important to Jewett's work, there also is lack of clarity about how Hetty was rescued and returned home. Jewett indicates that Hetty's husband, Thomas, personally undertook the redemption, but Emma Lewis Coleman says, "'Hitobl Goodin' was one of those redeemed in Oct 1695 by Mathew Cary" (Coleman, New England Captives Carried to Canada I [1925]: 185-186). Vaughan and Clark in Puritans among the Indians indicate that Hetty Goodwin was among the twenty-two prisoners brought back to Boston from Canada by Matthew Carey/Cary aboard the Tryal in October-November, 1695 (157).

Finally, whether Three Rivers in Canada would be seen as a "northern wilderness" in comparison to the Goodwin farm at Berwick is a subjective judgment. Certainly Berwick was home to Hetty and her husband was there, and she seems to have been eager to return, in comparison to other captives from King William's War (1689-1697), who voluntarily remained behind when Matthew Carey offered an opportunity to return. Still Three Rivers, as a frontier village, was not unlike Berwick.

[ Top of Page ]

Hetty Goodwin's Grave in Old Fields Cemetery

by Terry Heller, 2003

Lord Gormanstown (30):

The Lords Gormanstown, Howth, and Trimlestown are all remembered

by Master Sullivan in Chapter 30 as fancy dressers when

attending the theater in Dublin during Sullivan's youth,

probably in about 1720. All three families were prominent among

the nobility in Dublin in the 18th century.

Samuel Fitzpatrick describes brilliant

social gatherings a few years later at the New Gardens of the

lying-in hospital in St. George's Lane. The decoration of the

assembly room

"... left nothing to be desired. Adorned with fluted Corinthian pilasters, with a handsomely decorated ceiling, bright with gilding and brilliantly lighted, when filled with a motley throng including the elite of the nobility and gentry attired in the gorgeous and picturesque costumes of the period, it must have presented a striking spectacle.

"There was to be seen the portly figure of Lord Trimleston dressed in scarlet, with full powdered wig and black velvet hunting-cap; the elderly, middle-sized Lord Gormanston in a full suit of light blue; Lord Clanrickard in his regimentals; while Lord Strangford wore under his coat his cassock and black silk apron to his knees, and the clerical hat peculiar to these times, and Lord Taaffe appeared in a whole suit of dove-coloured silk" (Chapter 6).

Old Master Hackett: Two

Hacketts, William and James, were well-known ship-builders in

Portsmouth, NH, prior to and after the American Revolution.

According to The Diary of Ezra

Green, The Ranger "was built 1777, on Langdon's

Island, Portsmouth Harbor, by order of Congress, under the

direction of Colonel James Hackett." Langdon's Island

is now known as Badger Island. S. E. Morisson says that the Ranger's

designer was William Hackett and that Hackett's

son-in-law, Tobias Lear was in charge of construction. Morison

also points out that there is no surviving picture or plan for

the Ranger, so that all illustrations of the ship are

reconstructions (104).

Ray Brighton, Port of Portsmouth

Ships and the Cotton Trade: 1783-1829 (1986), says that

William Hackett (b. 1739) of Portsmouth was the master builder,

and that his cousin, James Hackett, "master-minded construction

of the Continental warships Raleigh and Ranger"

(145). William and James operated a shipyard together beginning

sometime prior to 1774. They worked on the America,

which was promised to Jones later in the war but given to

France, and also were responsible for building the Caroline

in 1800. James's last commercial vessel was completed in 1811

(190). George Henry Preble, History of the United States

Navy-Yard, Portsmouth, N.H. (1892) lists the company

building the Ranger as Hackett, Hill & Paul,

Shipwrights (12-14). Other sources indicate that James served in

the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, fighting at

the Battle of Saratoga, among others. See: Naval Documents

of the American Revolution 1775 v. 2, (616-7), Charles H.

Bell, History of the Town of Exeter, New Hampshire

(Exeter: The Quarter-Millennial Year, 1888), and State

Papers of New Hampshire: Rolls of the Soldiers in the

Revolutionary War. May 1777 to1780. v. 15.

[ Top of Page ]

Major Tilly Haggens and Nancy,

his sister (Haggins / Higgins):

Though there is at least some basis in

history for Jewett's protrayal of Tilly and Nancy Haggens,

Jewett has created versions of them that are almost completely

fictional. It is not clear why she has done this, whether

because she lacked information about them or because she

particularly wanted them to have the features she gives them.

Since she presents Tilly as an old-fashioned, admirable, and

somewhat wild action hero, her portrait at least suggests the

features she believed made up such a figure.

The following entry will review

what Jewett tells about Tilly in the novel, provide background

on what we are told, and finally present information about the

problems raised by these materials.

Jewett's Tilly Haggens

In Chapters 1 and 8, Jewett presents

Tilly as the builder of the house that became her family's home

and eventually her own home, the Jewett House at the corner of

Portland and Main in South Berwick. She attributes his rank of

major to participation in the Indian Wars. In Chapter 2, he says

that he brings several strains into "our nation's making,"

suggesting that he might have become a parson because of his

inheritance from his grandmother, "a saintly Huguenot maiden,"

except that his grandfather "a French gallant" had run away with

the maiden. He sees himself as divided between these two

heritages. This division is reflected in his account of his

name: "My family name is Huyghens; 'twas a noble house of the

Low Countries. Christian Huyghens, author of the Cosmotheoros,

was my father's kinsman, and I was christened for the famous

General Tilly of stern faith."

In Chapter 8, Jewett shows Tilly in

what is now the Jewett house, with his older sister, Nancy,

living out his old age as a successful gentleman in the large

new house he has built.

Christian Huyghens, also Huygens or

Christiaan Huyghens, (1629-1695) was a Dutch astronomer,

mathematician, and physicist. His Cosmotheoros appeared

in 1698. Johann Tserclaes Graf von Tilly (1559-1632), according

to Encarta Encyclopedia, was a "Flemish field marshal,

born in Brabant (now part of Belgium). At the outbreak of the

Thirty Years' War in 1618, he was made commander of the armies

of the Catholic League. He won (1620) the Battle of Wiesserberg

(White Mountain) near Prague; defeated (1622) the Protestant

forces at Wimpfen (now Bad Wimpfen, Germany); and conquered

(1623) the Lutheran prince Christian of Brunswick at Stadtlohn,

Germany. He was then created a count of the Holy Roman Empire."

In the history of Tilly's name and ancestry, we see reflected

both sides of the Catholic-Protestant conflicts that form a main

feature of the background of the European colonization of North

America and that, to some extent, are playing out in the

American Revolution.

The Historical Tilly Haggens and his family.

(Special research assistance: Norma

Keim, Connie Higgins Smith, Glen Corbin, Martha Sulya)

Tilly Haggens's (d. 17 August 1777)

actual ancestry is Irish. So far as has been discovered, he had

no sister, Nancy, though his daughter Nancy became the owner of

the Jewett house in South Berwick and sold it to Thomas Jewett,

Sarah's great uncle, in 1839. It was Tilly's son, John Haggens,

who built (beginning in 1774) and occupied the house where we

see Tilly and Nancy in the novel. Tilly's military background in

recent colonial wars is correct, and his love of spirits may

derive from the indication in local records that he was the

first tavern-keeper in South Berwick in 1767. The historical

Tilly had been dead about 6 weeks when The Tory Lover

opens.

According to 21st-century descendants,

Fergus O'Hagan and his brother, Tilly, arrived in America around

1740 and settled in Maine. With them was Fergus's small son,

Edmund. They are thought to have come from County Tyrone in

Ireland. According to Willie O'Kane's "Surnames of County

Tyrone" (tyrone.local.ie.content/31100.shtml/genealogy), the

O'Hagans were one of the principal families, the founder of

which was named Fergus.

G. T. Ridlon, in Saco Valley

Settlements and Families, says "Tilly Higgins came from

Ireland and sat down in Berwick; his brother Fergus settled in

Scarborough" (727).

The Woodsum Family in America

by Joseph C. Anderson II, with Maine Research by Lois Ware

Thurston (1990), describes Tilly's family (19-20):

Mary [Woodsum], born by 1725 as she "owned the covenant" on 16 February 1742/3 indicating she was at least 18 years old (NEHGR, 82 [1928]:214) and baptized 16 April 1732. She was alive on 13 June 1781 when a debt was paid to her from the estate of her sister, Sarah (York County Probate #20796). She married TILLY HIGGINS (NEHGR, 74 1777 [1920]: 194) who died Sunday morning, 17 August 1777 (id., 74 [1920]: 192). Higgins, the first tavern keeper in Berwick, Maine, was also "an importer and trader in South Berwick, Maine in 1744. He planted some of those now beautiful elms in South Berwick; particularly those in front of the house which he built next to the Congregational Church..." (John Wentworth, LL.D., The Wentworth Genealogy: English and American, 2 [Boston MA, 1878): 40-41). It has been claimed in at least two publications that Tilly Higgins married Mary, daughter of John and Mary Woodsum (ibid.; G. T. Ridlon, Sr., Saco Valley Settlements and Families [Portland ME, 1895] 1209 in footnote). The only John and Mary Woodsum to whom these sources may be referring are John2 and his wife Mary (Brackett) Woodsum who were married in 1747. However, it is impossible that John2 and Mary (Brackett) Woodsum were the parents of "Mary wife of Tilly Higgins" since Mary had a first child in 1742 and was old enough to "own the covenant" in 1742/3. Therefore, it is judged that Tilly Higgin's wife was actually Mary2, daughter of Joseph1 Woodsum.The Woodsum Family in America provides a good deal of information about Mary Woodsum's family, since her father is the founder of the line explored. It is noteworthy that this family was involved in a good deal of sexual scandal in Berwick before 1725, including adultery and producing children out of wedlock.

The Wentworth Genealogy by John Wentworth (1878) has this note on Tilly: "Tilly Higgins was an importer and trader in South Berwick, Me., in 1744. He planted some of those beautiful elms in South Berwick; particularly those in front of the house which he built (next to the Congregational church), which place is still owned by his descendants" (40).

Probably it should be noted that the Congregational Church located near what is today the intersection of Rts. 4 and 236 in South Berwick, was built after Tilly built his house, but presumably, they did stand next to each other.

The Woodsum Family in America lists Tilly's children; [I have added death dates for John and the second Edmund]:

Children (HIGGINS) of Tilly and Mary2 (Woodsum) born at Berwick, Maine (Tilly Higgins will, York County Probate #7983; NEHGR, 74 [1920]: 42, 184, 194; NEHGR, 82 [1928], 214, 216,218,325):Though it is not yet known when Tilly Haggens achieved his rank of major, he is listed as private Tilly Hagins in "The Blue Troop of Horse," William Pepperell's regiment from "Barvick" that went to Louisburg in 1757. Old Eliot 2 (February 1898) 28.1. John, born 19 September 1742, baptized at Berwick, Maine 16 February 1742/3, married Lydia Chadbourn. [John died before 29 March 1822, when an inventory of his property was completed].

2. Abigail, baptized at Berwick, Maine 8 July, 1744. Probably died young as she is not mentioned in her father's will.

3. Edmund, baptized at Berwick, Maine 30 March 1746 Probably died before 1760 when second child named Edmund was born to Tilly and Mary Higgins.

4. Anna, baptized at Berwick, Maine 6 March 1747/8, probably died young, as she is not mentioned in her father's will. [Note that John S. H. Fogg in "Graveyard Inscriptions from South Berwick" (NEHGR 10, Jan 1856, p. 58) records "Here lyes the body of Ann Haggens, died Jany 26th 1748 aged 4 years and 6 months." While it is possible, it is not certain this is the same Ann / Anna.]

5. Mary, born 23 March 1750, died 15 January 1777, married Paul Wentworth.

6. Sarah, born 23 December 1752, married Captain James Holland of Portsmouth, N.H.

7. Daniel, born October 1755, baptized at Berwick, Maine 9 November 1755.

8. Elizabeth, born 8 July 1757. Unmarried on 16 July 1777 when Tilly Higgins made his will.

9. Edmund, born 16 January 1760, married Susanna Hamilton. [Died 29 November, 1827, according to his stone in the Portland Street Cemetery in South Berwick. Major Edmund Haggen's family plot stands next to the Theodore H. Jewett plot].

There is confirmation of Tilly's children in Records of the First and Second Churches of Berwick, Maine, which shows the baptisms of Abigail, daughter of Tilly Higgins, July 8, 1744; Edmund, son of Tilly Higgins, on March 30, 1746; Anna on March 6, 1747; Mary on April 1, 1750; Sarah on January 28, 1753. Tate has Daniel Higgins "raising a grist mill at the foot of the lower mill at Salmon Falls, Berwick side," March 23, 1775. And he records the marriage of "Sarah, a daughter of Tilly Haggens to Captain John Holland" on Thursday 21 May, 1772; and the death of "Mary Wentworth, the oldest daughter of Tilley and Mary Higgins and wife of Lieutenant Paul Wentworth" on Wednesday, January 15, 1777 [Note that her older sister Abigail seems to have died before 1777 -- see above list of children of Tilly and Mary]. Captain Nathan Lord marries an Elizabeth Haggens in 1784, and this is likely to be Tilly's daughter.

This last marriage may be of some significance to Sarah Orne Jewett, for it appears that Nathan and Elizabeth's daughter, Elizabeth (March 31, 1791-1867), in 1816 married Thomas Jewett, Sarah's great uncle, and became her great aunt; she also became the mother of another Sarah Orne Jewett, who died apparently as a result of childbirth in 1864.

The above records suggest that Tilly moved to South Berwick at about the time of his marriage, since we have found no record of his presence in South Berwick before 1743, when he purchased land from "William Lord of Berwick" (York Deeds Book 24 p. 279). In this transaction, he is listed as a shopkeeper, as he is again in several other records of purchases in York Deeds books. He chaired the December 25 town meeting in 1755, suggesting that by that time he had become a person of influence in the community.

The Chadbourne family genealogy (available on CD) provides this basic information about Tilly's first son:

"JOHN HAGGINS, b Berwick 19 Sep 1742, d 1822, son of Tilly and Mary (Woodsum) Haggens. John was likely a trader of S Berwick. In 1744 his father may have planted many of the elms in town. He or his father built the Jewett house in 1774."

The Chadbourne genealogy lists the 12 children of John and Lydia Chadbourne Haggins (1746-1815), married in Berwick 1 May 1765, daughter of Judge Benjamin Chadbourne -- see above:

1. Lydia, b 17 July 1766, d 25 Aug 1787.(From Chadbourne Family Genealogy: Information on this family written by John Frost and Dotty Keyes).

2. Anne or Nancy, b 16 Apr 1768, d 1847, unm resident of Boston when the house was sold to Dr Thomas Jewett in 1822. [Presumably this should read Thomas Jewett in 1839.]

3. Mary (or Martha), b 15 Mar 1770, prob m Isaac C Pray of S Berwick and Boston, 3 ch. [Berwick Vital Records shows the marriage of Polly Haggins and Isaac C. Pray on 18 January 1809].

4. John, b 18 Feb 1772, d 7 Sep 1778.

5. Benjamin, b 6 June 1774, d ca 1816 (Chase Charts, 1858), unm.

6. James, b 16 June 1777, d by 1839, m 14 Apr 1819 Eunice Marsh (or March), d a widow 1839.

7. Sarah, b 24 June 1778 (Chase Charts), d Wells 4 Sep 1810, m 24 Nov 1807 Tristam Gilman Jr, b 25 Feb 1780, d Wells 25 Mar 1828, at least 2 ch.

8. Edmund, b 7 Oct 1780, m Elizabeth Rollins, d 16 July 1809, 1 ch.

9. Patty, b 8 Feb 1783, d 9 Jan 1834.

10. Tilly, b 23 Mar 1785, living 1822.

11. Betsey, b 25 Feb 1787, d 28 Apr 1809.

12. Daniel, b 25 Aug 1789, d 23 Sep 1801.

"Tilly Haggens's House" / Sarah Orne Jewett House

by Terry Heller, 1996

Who built the Haggens / Jewett House

Partly because of Jewett's vivid

portrayal of Tilly as builder and occupier of what became the

Jewett house, some people have believed that he rather than John

was the first builder and occupier. However, there is ample

evidence that Tilly's residence was at what is now the

intersection of Routes 236 and 4, near the current Federated

Church.

We can see that in 1878, the lawyer,

John Wentworth, believed that Tilly had built his own house next

to the Congregational church in South Berwick, though the church

was built some time after Tilly would have built his house.

Alfred Catalfo's master's thesis,

"History of the Town of Rollinsford" includes "The Diary of

Master Joseph Tate," who was a schoolmaster in Rollinsford, when

it was known as Somersworth. In this diary appears this passage:

"Mr. John Higgins raised a new house at the turn of the ways

near Mr. Robert Rodgers on Berwick side on Thursday, April 7,

1774." Tate also records Tilly Higgins's death on Sunday, August

17, 1777.

Master Tate distinguishes Tilly from

John, and in Records of the First and Second Churches of

Berwick, Maine, Tilly and John are separate persons as

well, father and son. This is important because Jewett seems to

conflate father and son into a single character, and a number of

writers have accepted this conflation as fact, seeing Tilly as

the builder and later a benefactor of the Berwick Academy.

Tilly's son, John, was 15 years old when the siege of Louisburg

took place, and he almost certainly did not become a major

during the French and Indian wars, as Jewett tells us Tilly did.

Tilly himself was dead for more than a decade before the Berwick

Academy was founded.

Where Tilly lived when he wrote his

will seems clear. A transcript of his will -- proved 9/16/1777

in York Probate -- in the possession of the SPNEA Jewett House,

shows he left his son Edmund "all my land on which I now dwell

at Quampegan in Berwick on the E side of the main road w/ new

road thru it. Btwn Nathan Lord and Robert Furness w/ bldgs &

appurtenances on land ....."

A copy of a road survey map at the Old

Berwick Historical Society, dated 1805, shows two Haggens

dwellings in what is now the town center of South Berwick, the

current Jewett house is called Mr. John Haggen's house, and at

what is now the intersection of Routes 4 and 236 is "the elm in

Majr Haggen's old garden." The York County Atlas of 1872

shows a house at this location marked as belonging to E. Haggens

(presumably, Edmund's son, Edmund), though we cannot be sure

this is the same house in which Tilly lived and which he willed

to his son, Edmund. This location would, however, place it next

to the Congregational church, as does Wentworth's note. Tilly's

son, Edmund, died intestate. The inventory of his property (Inv

39-342; 2 Feb, 1829, York County Probate v. 39 p. 341-2)

includes two houses: "Homestead in South Berwick. A dwelling

house, and buildings and 12 acres 40 rods of land on easterly

side of the road" and "Old house and 96 acres 150 rods on the

westerly side of the road." The second house may still be

standing, but this has not been determined.

It would appear that the house Tilly

left to Edmund was magnificent in its day, whether it was the

"homestead" or the "old house," standing above and commanding a

view of the Upper Landing with its wharves and mills. In the

entry on Jonathan Hamilton, Hamilton says that he expects his

new house to be a "finer house than Tilly Haggens's." That the

1805 map speaks of the elm in Major Haggens's old garden

suggests that perhaps by that date the original Haggens house

was gone. However, John Wentworth implies in 1878 that at least

one house remains occupied: Tilly "planted some of those now

beautiful elms in South Berwick; particularly those in front of

the house which he built (next to the Congregational Church),

which place is still owned by his descendants" (John Wentworth,

LL.D., The Wentworth Genealogy: English and American, 2

[Boston MA, 1878): 40-41). It is somewhat puzzling that such a

house could have disappeared since 1878 without some commentary

in town history, but this has not yet been found.

There also remains confusion about the

history of ownership of the John Haggens house that became the

Jewett house. Stories vary from the observable facts, probably

because it appears that from 1819 (according to SPNEA) or soon

after 1821 (according to Paula Blanchard) Sarah's grandfather,

Theodore F. Jewett, began to occupy the John Haggens house.

Since John died in 1822, this would be a good possible date for

the new occupancy, but we have little hard information about

what happened and why.

Though this is difficult to determine

with exactness, it appears that the ownership of the land on

which the house and its outbuildings stood became unclear when

John and Edmund (sons of Tilly) died intestate between 1822 and

1827. The estates were settled by 1830, and it seems that Nancy

Haggens became the main owner of the Jewett house and lands.

Blanchard states that Theodore F.

Jewett moved into the Jewett house with his second wife, Olive

Walker, soon after their marriage in 1821. Though Blanchard

states that T. F. Jewett bought the house at that time, in fact

the purchase was not completed until 1839, and SPNEA research

suggests that Theodore Furber Jewett rented the property from

John Haggens's estate at first. The house did not change hands

legally (by deed) until 1839. On May 27, 1839, Thomas Jewett

purchased from Nancy Haggens and the estate of John Haggens

several parcels of property (York Deeds 164:267). On the same

day, Thomas sold the "mansion house" and lot to his brother,

Theodore (York Deeds 164:269).

The Society for the Preservation of New

England Antiquities is responsible for the Jewett house. SPNEA

believes the house was completed in about 1778 in its original

form, but that a new kitchen appeared as the Haggens family

grew, before it was sold to the Jewett family. When Haggens

raised the house in April 1774, Lydia was pregnant with their

fourth child. By the time it was completed there were probably 7

children living at home.

It would make sense for Tilly's son

John to be building a good-sized house and eventually

contributing to the Academy, given that his family was expanding

and that he and his family were major property holders in the

northern parts of South Berwick. According to tax valuation

information in Hamilton genealogy documents at the Old Berwick

Historical Society, "Tilley Higgens" was about in the middle of

the seven wealthiest men in South Berwick in 1771. In 1798, his

son, John, is about the second wealthiest after Jonathan

Hamilton.

[ Top of Page ]

Jonathan Hamilton (1745-1802)

In the novel, Hamilton is presented as

a serious businessman and an active patriot, seemingly involved

militarily, but in a vague way, in the Revolution. For

example, in Chapter 35, he is said to be serving in General

Washington's own regiment. He is unmarried and deeply

involved in his work. In Chapter 18, she has Dickson say

that Hamilton began his career as an itinerant shoe repairer,

but this has not been confirmed in research.

Jewett clearly has fictionalized

Hamilton in some key ways. He had no sister, Mary, but in fact,

had married Mary Manning in 1771. He had three sisters,

according to a family genealogy kept by the Hamilton House in

South Berwick: Elizabeth (bpt 1742), Sarah (bpt. 1744), and

Deborah (bpt 1744). Details of his military service have

not been found. Hamilton was an astute businessman with

far-flung trading interests.

Jewett also shifts time a little,

presenting Jonathan Hamilton and his business associate, John

Lord (see below), in 1777 as they were, financially and in

business terms, in 1787, about the time Hamilton House was

completed.

In "The Old Town of Berwick," Jewett

says: "The richest founder of Berwick Academy, the oldest

literary incorporation in the state, was Col. Jonathan Hamilton,

a shipowner and merchant, who from humble beginnings accumulated

his great fortune in the West Indian trade. He was born on Pine

Hill, in the northern part of the town; but built later the

stately old house at the Lower Landing, and lived in it the rest

of his life, with all the magnificence that was possible in his

day. On his archaic looking tomb, in the Old Fields burying

ground, the long high-sounding inscription ends with the solemn

words, 'Hamilton is no more.'"

There is disagreement among sources about Hamilton's ancestors. Margaret Kugelman Hofer's informative essay, "Citizen, Merchant, Community leader: A New Interpretation of Jonathan Hamilton" in the files of Hamilton House (SPNEA) includes a "Genealogy of the Hamilton Family." Following is a summary of Jonathan's ancestry as reported by Hofer, and a discussion of the confusion over the identity of his grandfather.

Paternal Great-Grandparents:

David Hamilton (d. 28 Sept. 1691) and Anna Jackson, married

1662.

David Hamilton was deported in chains from Scotland, settled on

what is now Sligo Road, southwest of South Berwick in New

Hampshire, where he was eventually killed by Native Americans.

Grandparents:

The Hamilton House genealogy lists Bial

and Abigail as Jonathan's grandparents, but this turns out not

to be clear. Two of David Hamilton's sons were Bial (b. 1676)

and Abiel or sometimes Abel (b. 1680). Everett Stackpole in Old

Kittery and her Families (1903) is a main authority on

this topic; he says that Bial Hamilton married first Mary Hearl

sometime before 1715 and then later married Abigail Hodsdon

(daughter of Joseph Hodsdon and Margaret Goodwin) in 1721. By

this second marriage, he became the father of Joseph Hamilton

who was Jonathan's father.

However, the town records of Berwick at

the Berwick Town Hall, near the end of volume 1, list the

marriage of Abial Hambleton and Abigail Hodsdon on December 26,

1721; here also are listed the births of two children to Bial

and Mary Hambleton: Keziah on 30 March, 1715, and Solomon on 6

June, 1716. (Stackpole also indicates that Abiel was first

married in 1705, to Deborah, and that there is evidence they had

some children.)

So, it seems uncertain whether it was

Bial or Abiel whose second wife was Abigail and who became

Jonathan's grandfather, since it seems agreed that Abigail was

Jonathan's grandmother.

Parents: Joseph Hamilton (bpt. 1726) and Elizabeth.

Jonathan was the youngest of four

children, baptized in 1745 or 1746.

Though Joseph's death date is not

known, he received a jury appointment from the town of Berwick

on March 12, 1749, so his death was after that date.

Jonathan married twice: Mary Manning 8

February 1771, and Charlotte Swett of Exeter 4 April, 1801.

These marriage dates are confirmed in Vital Records of

Berwick ..., Mary (118) and Charlotte (47). However,

Stackpole has him marrying three times. This has not been

confirmed; and it is useful to know that two Jonathan Hamiltons

appear active in Berwick affairs after 1770, and Stackpole's

list of the third generation of Hamiltons includes several Johns

and Jonathans (488-491).

Jonathan and Mary had nine children;

there were no children by the second marriage.

Hofer also reports on Hamilton's ships

and wealth, beginning with his operating two privateers in 1780,

and then 12 brigs, ships, and schooners from 1785 until his

death. In 1771, Hamilton's net worth for tax valuation was 9

pounds, compared to 94 pounds for the leading businessman of the

area, Benjamin Chadbourne. In 1798, Hamilton was one of the two

leading property holders, with a tax valuation of about $6200,

about the same as John Haggens at $6300. However Hamilton held

considerable property outside Berwick, including the sea-going

vessels, a wharf and warehouse in Portsmouth, and plantations in

the Caribbean.

The stately Hamilton house was

completed after the Revolution in about 1788 -- various dates in

the 1780s are given in different sources. Paula Blanchard in Sarah

Orne Jewett suggests that Jewett may not have known the

date of the house's construction, though by the time she

completed The Tory Lover, she had helped to arrange for

Emily Tyson and her step-daughter, Elise, to purchase and

restore the property. In "River Driftwood" (1881), Jewett

imagines John Paul Jones visiting the house (342).

Various sources affirm that David

Moore's mansion, which occupied the site before Hamilton House,

was equally impressive, but that it burned between 1777 and

1783. The "gossipy" Goodwin Diary by Mrs. Ichabod Goodwin

(Sophia Elizabeth Hayes) from 1885 (Old Berwick Historical

Society) reports this as heard from Mrs. Raynes, July 31, 1884,

"On the place where the 'Hamilton House' now stands was a house

built and occupied by David More, which was burned, there was

also another large house built by Wm. Rogers ... nephew of Mrs.

More. Both of these houses were finer than the Hamilton House."

She goes on to report that the Rogers house was eventually moved

without damage to Portsmouth by gundalow. Even if John Paul

Jones did not visit Hamilton house itself, he could well have

visited a similar house at the same site. However, I have found

no documentary evidence that he travelled up-river from

Portsmouth, where he oversaw the completion of the Ranger.

Drawing upon Marie Donahue in "Hamilton

House on the Piscataqua," Down East (1975), this

account appears in Cross-Grained & Wily Waters, edited

by W. J. Bolster (2002): "During the American Revolution,

Jonathan Hamilton of South Berwick went privateering and amassed

a fortune. With peace he purchased thirty acres of land along

the eastern shore of the Salmon Falls River from Woodbury

Langdon. There, on a high bluff, Hamilton built a Georgian-style

mansion in 1785 that, he boasted, would be a 'finer house than

Tilly Haggens's' ..." (178).

In The Old Academy on the Hill:

1791-1991, Donahue says of Berwick Academy's founders:

"Probably the most affluent of these gentlemen was Colonel

Hamilton, a merchant and shipowner, whose great gray house

standing on a knoll high above the broadest reach of the

Newichawannock River reflected not only his wealth but his

superb taste. Born in Berwick in 1745, he grew up in the Pine

Hill section of the town, where his companions included the

Sullivan brothers, John and James. Though, like the Sullivans,

Hamilton sprang from humble beginnings and had little formal

education, he had a shrewd business head and an eye for a sharp

deal. In a letter dated December 27, 1790 to Captain Nathan

Lord, who was commanding Hamilton's brig Betsey, Hamilton

urged him to "shorten your tarry in Tobago" in order to take

advantage of the high prices prevailing in the Portsmouth

market. "If you leve a Small part of your affects behind for the

Sake Gutting away befor any other Vessell you Will Leve it in

Such a Way as that the first Vessell after you may bring it --

but keep that From your Merchant untill you Gut all that you

can." A low C in spelling, perhaps, but an A+ in economics. By

the time he was thirty, Hamilton was a rich man, had acquired

the honorary title of Colonel, and was able to contribute

substantially to the subscription fund of five hundred pounds

raised by the founders for the erection of the first Academy

building" (23).

The Goodwin diary transcript at the Old

Berwick Historical Society provides interesting testimony about

Hamilton, from Mrs. Raynes, July 31, 1884:

"Col[.] and Mrs. Hamilton came from Pine Hill. They had several sons and daughters, one daughter married John R. Parker of Boston, another married Joshua Haven of Portsmouth. The second Mrs. Hamilton was Mrs. Swett of Exeter, a cultivated lady. Mr. Hamilton's daughters wore full mourning when she appeared as a bride. Mr. Hamilton lived only 18 months after this marriage....The full inscription on Hamilton's tomb reads:

"Mrs. Swett of Exeter outlived him and received $60,000 of his property. She afterward married Gov. Gilman of Exeter, a great uncle of Mrs. Theodore Jewett, and received a large share of his property.

"Col. Hamilton died very suddenly. He had be[e]n walking in the field with his wife and complained of not feeling well, and died soon after entering the house. His sons were very dissipated and soon spent their patrimony...."

In memory of

JON HAMILTON Jn.r Esq.

Who departed this life Sept.r 26th 1802

Ætatis 57

Possessing those qualities which always ensure esteem:

of pleasing deportment

a firm, vigorous & enterprising mind,

a tender Husband

a kind & anxious Father

His zeal for order in Church & State, extensive business,

and publick spirit, rendered him a blessing to the community

a friend to religion & religious men

an agreeable companion

and a sincere constant faithful friend

As a merchant

extensively known & respected

his strict probity & exact punctuality secured him

the entire confidence of all that knew him;

the smiles of Heaven on indefatigable industry & the best

œconomy rendered him eminent as a man of property

But alas, neither wealth nor merit can bribe or evade

the grim tyrant death

nor repel the fatal shaft.

Hamilton is no more.