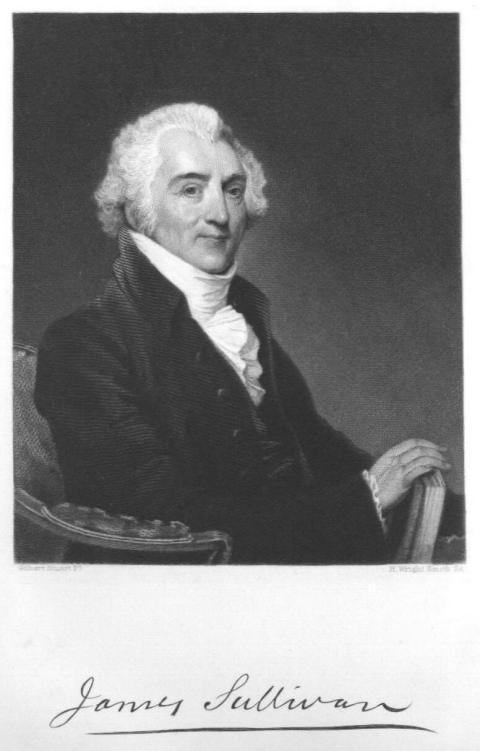

Selections from The Life of James Sullivan by Thomas C. Amory.

Boston: Phillips, Sampson & Co. 1859.

Supplement for The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne

Jewett

This is a probable source for Jewett as

she researched

The Tory Lover.

James Sullivan was a son of "Master" or John Sullivan, who helps Mary and Mrs. Wallingford to find influential friends in England. Although this book is about James Sullivan, it provides a good deal of information about his father and mother and also his brothers, two of whom are mentioned in The Tory Lover.

CHAPTER I. PARENTAGE.

THE Sullivans were for many centuries a numerous and powerful sept settled in the southerly part of Ireland, and are now extensively multiplied on both sides of the Atlantic. In common with the other Milesian families, they traced their origin to a very early period of history. The preservation of their national annals, as also those of each particular sept, was made the especial duty of the bards and chieftains of the ancient Irish, from the organization of the government under the sons of Heber down to the times when the country was thrown into anarchy and confusion by the progress of English invasion. It is an interesting and well-authenticated fact, connected with the history of Ireland, that, under Queen Elizabeth, one measure adopted for its more perfect subjugation was an order to collect from the national and private repositories these records, that by gradually weakening, through their destruction, the spirit of clanship, the land might become an easier prey to the spoiler. This order was only partially obeyed; and in many of these ancient chronicles, or psalters as they were called, which have been preserved, frequent mention is made of the O'Sullivans and their chieftains. Many of the name gained glory by their exploits in the field, or were otherwise honorably remembered, and their race, to use the words of Sir William Betham,* a standard authority on such subjects, in point of antiquity and early preeminence, can vie with the most distinguished in Europe.

For many centuries prior to 1170, when the English first arrived in hostile array upon its shores, Ireland had been as highly civilized as any part of Western Europe; and its schools and colleges, in the days of Charlemagne and for a long time afterwards, were the resort of priest and noble from England and from many of the continental nations. During this period, and down to a comparatively recent era, the O'Sullivans possessed extensive territories in the Province or Kingdom of Munster; and along the shores of the Bay of Bantry, the banks of the Kenmare, and up through the superb passes and defiles of the Lakes of Killarney, celebrated as among the most beautiful scenery in Europe,** their chieftains exercised an independent sovereignty. The mouldering ruins of the Castles of Ardea, Dunkerron, and Dunboy, still remain the mournful monuments of their former prosperity; while more enduring testimonials of their virtues, valor, and love of country, fill some of the brightest pages of their ancient annals. No one can read the history of the English conquest, slowly extending through so many centuries its steady and desolating progress, and contemplate without sensations of horror the ruthless barbarity that marked its bloody footprints, or without mingled emotions of admiration and sadness the gallant and long-protracted struggles of the people, and their final unhappy destiny. In their social system, which was rather patriarchal than feudal, and better suited to promote the welfare of an agricultural community beyond the reach of foreign war, than one placed so near a powerful and warlike nation like the English, there were inherent defects which rendered impracticable any combined resistance to foreign aggression. Could they have been united, and loyal to one common sentiment of nationality, Ireland eventually, from her inferior power and resources, might have become a dependency of Great Britain; but the properties and liberties of its people would have been respected, and they would have been spared that terrible destitution and servitude which have driven so many of them into exile.

The comparative power of the conquerors increased with each successive century; and the native races, alienated and divided by feuds and jealousies fostered by English policy, all industry being discouraged by the presence of hostile armies, fell off more and more from their earlier grade of civilization; while their enemies, absorbing their substance and gaining vigor from their decline, secured their conquests by keeping the remnant of the inhabitants in poverty and ignorance. If, under these discouragements, there was no progress in the arts of life, and little instruction among the people, this applied with less force to the more affluent; and their chieftains, educated on the continent, compared favorably in accomplishments and all the higher sentiments and graces of civilization with any similar class in Europe. Surrounded at home by the vicissitudes of deadly warfare, the uncertainties of life increased their sensibility to religious influences, and they were as devoted to their church as tenacious of their national independence. The English rule, long confined to what was called the pale, the country immediately surrounding the capital, gained gradually in its sweep over the island, until it extended to the sea. The contest assumed the character of civil war, and those reduced to submission were retained in subjection by confiscations and proscriptions. Often, that a better pretext might be found for stripping them of their inheritance, the native chieftains were instigated, by their rapacious and wily adversaries, to acts of resistance. Religious persecution, an admirable invention of the spirit of evil, came in ready aid to accomplish the same objects; and thus the soil in time became vested in the Saxon and Protestant.

Remote from the English pale, and their country protected by its natural defences, the O'Sullivans for numerous generations retained their territory unmolested. In the fifteenth century, indeed, for a short period it fell into the possession of the stranger; but, recovered by force of arms, remained for the most part in their quiet, undisturbed enjoyment down to the latter days of Queen Elizabeth. During the long-protracted struggle of Ireland for nearly five hundred years for national existence, they were ever among the most stanch and self-sacrificing of its defenders. Other families were their superiors in wealth, and in the number of their adherents, and perhaps more frequently mentioned with distinguished encomium; but few were more efficient in service, or less selfish in their patriotic devotion to their country.

A long succession of O'Sullivans, hereditary princes of Beare and Bantry, whose names are recorded in the genealogical works of Ireland, and mentioned honorably in its annals, were for centuries independent chieftains of the southerly portions of Munster. Their rule extended over hundreds of square miles of territory, and was recognized by thousands of attached adherents and followers. Bordering on the sea, and deeply-recessed bays which indent the south-westerly shore of the island, like their Iberian progenitors they were much devoted to maritime adventure, and had constant intercourse with France and Spain. The English forces made occasional forays into the province, but only in the seventeenth century reduced it to complete subjection; and this after the destruction of a large portion of its inhabitants, and by reducing it to a desolate wilderness. Before the middle of the sixteenth century the princes of Beare acknowledged no allegiance to the English monarchs; and in 1531 the commander of an English vessel, who had ventured to capture a Spanish fishing-smack in the Bay of Bantry, was hung by order of the chieftain.

In the earlier years of Queen Elizabeth, Daniel, head of the sept, dying, leaving as his heir a son in infancy, his brother Sir Owen, the next in succession of full age competent to rule according to the Brehon law, succeeded as Tanist. Sir Owen, in 1570, recognized the supremacy of the English crown, and, surrendering the territories to the Queen, received back a grant of them by patent. When his nephew, Daniel, came of age, he was acknowledged chief of the sept; and upon his petition, in 1593, to be reinstated in his rightful inheritance, it was decreed by the Queen's deputy that Sir Owen should surrender to Daniel the Castle of Beare, its haven and demesnes; deliver up to his younger brother, Sir Philip, the Castle of Ardea and the lands adjacent; retaining for himself the Castle of Bantry and its dependencies. This was agreeable to the then existing policy. The native princes, weakened by this subdivision of their territories, and by the jealousy naturally engendered by the infraction of rules of tenure so long established, were rendered too feeble and too much divided among themselves to be formidable to the government. Many, provoked into hostility, were driven into exile, while others were allured by grant of titles, or intimidated by fear of confiscation, into submission.

Zealously attached to their ancient faith, and with no respect for the new opinions, the nobles of the south of Ireland, when they perceived it to be the determination of Elizabeth to eradicate Romanism, formed, in 1588, for mutual protection, what was designated the Catholic League of Munster. They were soon involved in a war, which was waged with various fortune for fifteen years. After the defection of McCarthy More, Daniel O'Sullivan, Lord of Bearehaven, at the head of the confederacy, was left to bear the chief weight of English resentment. His clan rallied with their accustomed loyalty to his banners, and for a time he maintained, with some promise of success, a hopeless struggle with overpowering numbers. The long and gallant defence of his Castle of Dunboy, by a garrison of one hundred and forty-nine men against five thousand English armed with artillery, is one of the most heroic on record. Left to cope with forces superior in number, arms and discipline, he led his remaining followers through a country filled with the enemy, and, transporting them in boats, made of the skins of their horses, across the Shannon into Connaught, gained the advantage in several engagements by skill and bravery. Disappointed in the hope of finding sufficient force in Connaught to continue the contest with any chance of success, alone exempted from pardon, with Ellen, his wife, daughter of Owen O'Sullivan More, seventh Lord of Dunkerran, he went into Spain, where his son, for eminent services, was created Count of Bearehaven.

Several legends and ballads are still familiar to the people of Munster, founded on incidents in the romantic career of Daniel O'Sullivan Beare. One, it may possibly be interesting to mention, illustrating the devotion of a faithful adherent left in charge of the wife and child of his chief while they were in concealment among the mountains of Beare. Watching daily the movements of a large eagle procuring fish for its young from the neighboring waters, this faithful guardian climbed to its mountain nest, and brought down what was needed for the sustenance of the objects confided to his care.

Philip, a near kinsman of Daniel, who went also into Spain, wrote, among other works, an interesting history of Ireland in Latin; and others of the family have occupied distinguished positions in the Irish brigades in the French service, and in the modern history of Europe.

After the fifteen years' war under Elizabeth, from 1588 to 1602, the family of Beare and Bantry were deprived of a large portion of their territories, and, by successive confiscations under the Stuarts, that of Dunkerran became impoverished. In the year 1652, in the days of Cromwell, Daniel O'Sullivan More and his son John, were slain in the defence of their Castle of Dromanagh against the English forces, and by the end of that century both branches of the sept, the O'Sullivans More and the O'Sullivans Beare, who generally sided with the Catholics against the Prince of Orange, were divested of their remaining possessions.

By this reference to well-established facts in the history of Ireland we do not fear being charged with any disposition to keep alive painful memories, or to perpetuate the animosities of race. The sin and the shame of these ancient wrongs sleep with the centuries that are gone. Whatever principles of state policy, fortuitous or providential complication of causes, lent their aid in reducing Ireland to an English province, the course adopted was in accordance with the then generally admitted principles of conquest, and the same pursued by the vanquished, when themselves the invaders, towards their predecessors. Resentment is no longer rational, for, as respects the present, it has neither cause nor purpose. Just laws, and their well-regulated administration, have long since made Ireland an integral part of the British realm; and her people, now that for successive generations their blood has been mingled in marriage and shed to their common glory on innumerable battle-fields, have become one with the people of England. With the progress of enlightenment, character, industry and education, there, as elsewhere, are recognized as the essential forces controlling political power and social condition; and violence, though it may disturb the repose, can no longer affect the stability of its government. Here, in the New World, under the influences of education and more favorable opportunities of development, Celt and Saxon are gradually blending with the other elements of population, and distinctions of race rapidly merging in one general nationality.

John Sullivan, of Berwick, in Maine, father of General John Sullivan, of the Revolution, and of James, the subject of this memoir, was born in the city of Limerick, in Ireland, in the early part of the year 1692. His father, Major Philip O'Sullivan, of Ardea, a lineal descendant in the fourth*** generation from Daniel O'Sullivan Beare, was an officer in the Catholic army, and there is reason to believe one of those who, after the surrender of Limerick to William of Orange, preferring exile to submission to a government not of their choice, under the articles of the surrender, dated October, 1691, concluded to go with Sarsfield into France. Some months elapsed before vessels could be procured for their conveyance, and in this interval of delay John was born. Major Philip died soon afterwards, in France, of a wound received in a duel with a French officer. His widow, belonging to a wealthy and powerful family, which, through their chief, McCarthy More, had become reconciled to the government, resided in Ireland. The schools and colleges at home being closed to Catholics, her sons were, no doubt, educated on the continent, where there were several scholarships founded at different seminaries of learning, for the benefit of persons of the name.

After the death of William of Orange, the solemn covenants and conditions of the surrender of Limerick were violated by the Protestants without hesitation and without compunction. Irish Catholics, stripped of their remaining estates, or holding them at the mercy of their conquerors, their religious rites proscribed, the professions closed against them, were subjected to restraints, indignities, and the utmost ingenuity of persecution. Such was the condition of affairs in Ireland when young Sullivan, after the completion of his education, returned from the continent. Hopeless of change, and conscious of the futility of resentment, his early manhood glided away in sadness and humiliation.

The sister of Mrs. Sullivan had married Dermod, eldest son of Daniel O'Sullivan More, Lord of Dunkerran. The son of this marriage, educated also on the continent, continued loyal to the Stuarts, and is believed to have been the companion of Charles Edward, in 1745, at Culloden, and in his subsequent wanderings.**** A tradition exists among the descendants of John of Berwick, that, while a young man residing at home with his mother, he was the friend and correspondent of this cousin; and that an interview between the relatives, on board a French vessel of war off the Irish coast, exciting the suspicion of the English authorities, John was obliged to leave Ireland.

But the reason for his leaving home, according to the more usual and best authenticated tradition which has been transmitted in his family, was the course his mother saw fit to adopt in opposing his union with a young lady, of beauty and accomplishment, but one of a family not equal to his own in respectability and wealth; and whom she, a proud and high-spirited woman upon whom he seems to have been dependent, considered no suitable match for her son. She warned him that, should he disregard her wishes in this particular, he should derive no further aid from her; and finally concluded by peremptorily forbidding the marriage. He desired her to take a week for reflection before confirming her resolution, and told her that, should she persist in her opposition to his union with the lady of his choice, he would leave home and go where she would never see or hear from him again. When the specified period had passed without her showing any disposition to relent, he carried his threat into execution, and became an exile from his home and his country. The strength of his attachment to the object of his early love was never overcome, and when he was more than sixty years of age it is related that at the mention of her name he lost all control of his feelings. That his mother never actually heard of him after his departure, is abundantly proved by a letter from a relative in Ireland, written front Kerry, by a curious co´ncidence, on the same day that her son died at Berwick, and addressed to General Sullivan, whose revolutionary services had attracted attention to the existence of the father.

John Sullivan sailed from Limerick in 1723, and the vessel is believed to have been driven by stress of weather into York, in the District of Maine. On the voyage out his attention was attracted to a pretty child, then only nine years of age, named Margery Brown, who afterwards, when she had grown into womanhood, became his wife. Leaving home under circumstances to make him naturally careless of his future, he was obliged, upon his arrival in this country, to enter into an agreement with Mr. Nowell, the master of the vessel, to earn the money for his passage. Unaccustomed to labor, and finding the life irksome, he applied to Dr. Moody, of York, a clergyman celebrated for his benevolence, whose acquaintance he had made soon after his arrival, by a letter written, in order to prove his qualifications, in several, tradition says seven, different languages, soliciting his assistance in procuring more congenial employment. This application resulted in a loan sufficient in amount to cancel his obligations to Mr. Nowell, and enable him to open a school at Berwick. His young friend on the voyage, little Margery, probably indentured, as was usual among the poor in colonial days, he is said also to have redeemed from her indentures.

Under what circumstances Margery came to America is not known. Her parents may have died on the passage, or may have been too poor to provide for her when they arrived in this country. It is difficult to account otherwise for her redemption by Mr. Sullivan. He appears to have adopted her and brought her up as his own child. When she had reached the period of maidenhood she is said to have been unusually attractive; and one day, while drawing water at the well, a young man, better clad than the generality of the neighbors, came by, and engaged her in conversation. Fascinated by her charms, he on the spot proposed marriage, and doubtless, as she had been instructed in the event of such a contingency, she referred him to her father. The lover stated his case to Mr. Sullivan; but when, upon consulting Margery, it was ascertained that no such impression had been made upon her heart as would warrant consent to the proposal, Mr. Sullivan bade the over-eager suitor good-day, and, displeased with so much fervor without encouragement, with a gentle intimation that the further prosecution of his unwelcome addresses would be resented. These particulars were related not long since to the writer and a great-grandson of General Sullivan, by an aged lady, in her parlor at Berwick. In that same apartment, some sixty years before, she had received them from the lips of Master Sullivan himself, in the presence of his wife. The ancient couple had been to a funeral, and, making her a visit on their return, were detained there by a heavy shower.

Enlightened by this incident as to the nature of his own sentiments towards Margery, and discovering that he had himself already gained her affections, he made her, soon after, his wife. The disparity of age, for she was some twenty years younger than her husband, did not lessen their happiness; indeed, her greater dependence upon his superior experience served only to increase their mutual attachment. Although she did not at all times take kindly to his efforts to inspire her with a taste for knowledge, she was bright and sensible, and proved doubtless a better helpmate in the wilderness than if more highly educated. He was occasionally provoked by her violent ebullitions of temper, but she seems to have yielded ready obedience to his authority whenever he saw fit to exert it. Like all men possessed by any secret subject of sorrowful reflection, he shrunk from contention, and probably lived in his own recollections a life quite apart from his daily duties and employments, sharing but few of his deeper feelings even with his wife, who, from her own very different experiences in early days, could have had little power of understanding them.

They were married, to judge from the ages of their children, about 1735; and, soon after, he purchased seventy-seven acres of land in Berwick, bounded north-westerly by Salmon Falls River, where he resided during more than sixty years, up to the period of his death in 1796. The inducement to settle at Berwick being employment as a teacher, Mr. Sullivan zealously devoted himself to his duties, having at the same time two public schools, one for boys and one for girls, under his charge. These schools were open but a part of the year, and the instruction consisted of the ordinary branches necessary for the conduct of the common affairs of life. One of his pupils, Mr. Lord, recently deceased at the advanced age of ninety, and who for many years was his neighbor, spoke, shortly before his death, of his old master in terms of great respect and affection. He said that, if there were any disputes or misunderstandings among the neighbors, they were referred to Mr. Sullivan. He was called upon to draw all the wills, deeds, and other legal papers, needed in the simple rural community about him, and was their confidant and counsellor in all cases of trouble and difficulty. Mr. Lord described him as a tall, slender, but athletic man, six feet in height, with dark hair, black eyes, and florid complexion, very erect, of fine figure, and well proportioned. One still living speaks of him as a marked man in his personal appearance, of great natural abilities and mental cultivation. He was more fond of his books than of farm labor, and left his studies with great reluctance, at the solicitation of his wife, to attend to his stock or his harvest.

In 1765, when already past the usual limit of existence, he made a lease of his farm to his son John, on condition that John should educate his brothers for professional life, and provide for Mrs. Sullivan, should she survive her husband. But he lived on, in the full possession of his faculties and of his physical strength to a remarkable degree, till he had reached his hundred and fifth year. He had been always sufficiently familiar with Latin to read and speak it fluently; and, when over eighty, wishing to renew his acquaintance with French," he sent to his son, General Sullivan, at Durham, for a grammar, dictionary, and other books in that language, and four months after wrote him a letter in French, containing ingenious commentaries on the authors he had read." Dr. Eliot says that he spoke and wrote both French and Latin fluently when over a hundred. At this advanced period of life he planted an orchard, cut his own wood, and often drove his oxen to the blacksmith's, a mile distant from his home, yoking and unyoking them without assistance, and rode frequently on horseback to Durham, to dine with his son, General Sullivan, and back the same afternoon, the distance both ways being nearly thirty miles as the roads then were.

He was very temperate in his habits, never drinking ardent spirits. Honorable, friendly, and generally beloved, he passed on the quiet tenor of his way, and probably would have been soon forgotten, save by his descendants, had not the prominent part taken by his sons, in achieving the independence of the country, brought him into notice. As the instructor of many successive generations of his neighbors in the useful mysteries of reading, writing, and arithmetic, he acquired much influence over them as they grew into manhood. His means were, of course, extremely limited; but those about him were occupied in busy labor, and less importance was attached to differences of condition, and more, perhaps, to character, than in the present days of affluence.

His wife had come when a child to America. She had great natural strength of mind and energy of character, but living in seclusion, she was quite uncultivated, and her ways and manners those of the frontier settlement. Her peculiarities of temper are still remembered; but all speak with respect of her devotion to her family, and constant acts of kindness to her neighbors. If they were ill, she watched by their bedsides; and if in sorrow, was ever ready with kind words of consolation. "She was somewhat below the middle height, remarkable in her younger days for beauty and vanity; at all periods of her life for her talents and energy; and, if tradition speak true, also for the violence of her temper." While her husband was engaged with his schools she superintended the farm as well as the household; and in all her various duties was excellent as a wife and a mother. Her sons, very probably, inherited largely from her the ambition and industry that made them useful and distinguished.

From his not attending the religious services of the neighborhood, it has been conjectured Master Sullivan kept steadfast to the faith of his childhood. A lady, who visited him within a few years of his death, says she found him reading his Bible. There was, upon the table at which he was seated, a copy of Hervey's Meditations among the Tombs. He recommended it to her perusal, and engaged her in a conversation, interesting and instructive, which left a very vivid impression on the mind of his visitor. His hair at that period was of silvery whiteness, parted on his forehead, worn long and flowing over his shoulders; and, as she described him, attired in the long robe of dark flannel, which the aged were then accustomed to wear in such remote places, with a small, close-fitting cap or band on his head, with his appearance of high health, and that peculiar beauty which sometimes makes old age so attractive, the impression made by his good sense and cultivation was much enhanced by his outward appearance. It is a subject of regret that no portrait was taken of him at this period. Major Thomas Brattle, an intimate friend of Governor Sullivan, sent him, about the year 1800, an oil painting, called the Man of Moss, which was said to bear much resemblance to John of Berwick at an earlier period of life.

John Sullivan lived long enough to see his sons John and James distinguished by the grateful respect of their countrymen, and the country itself prosperous and happy under its new government. His son, General Sullivan, died in January, 1795, at Durham, and he, fifteen months later, ended his long life at Berwick, in May, 1796, having reached his hundred and fifth year. He was buried, according to the custom of that part of the country, on the farm where he had so long resided. His widow died in 1801, at the age of eighty-seven, and was buried by the side of her husband. Their son James erected over their remains a tablet to their memory; and, about 1850, Governor Wells, and others of their descendants, enclosed the spot with an iron fence.

There is much which strongly appeals to the admiration and sympathy of his descendants in the character and career of this venerable patriarch of his family in the New World. Arriving penniless on that then wild shore, without kindred, or any one to love but the pretty child whose pleasant ways had beguiled the sadness of his weary voyage into exile; with indolent habits, and unskilled to labor, yet courageously grappling with the necessities of his condition, and earning his own passage-money, and then that of his future wife, whom, as she bloomed into womanhood, he thus made more particularly his own; redeeming his farm from the forest, with his rifle ever at hand, and his ear on the quick to catch among the mysterious voices of the solitary woods the stealthy footfall or the savage warwhoop of the wily and merciless foe; teaching the rudiments to successive generations of the little community around him, who grew up to give him his recompense in their honor and love; instructing his sons out of the stores of his own mind and memory, for he could have had but few books in the wilderness, in the principles of right and wisdom which were to guide them through the perilous conflict, and render them of such distinguished service to their native land, -- one of them a leader in the first overt act of the Revolution, and all instrumental in requiting to England the wrongs inflicted on his ancient home beyond the sea, -- not that he was vindictive, but that his sense of justice was satisfied; of scanty means, and toiling hard for subsistence, yet living on cheerful and contented; just and reasonable enough in his own dealings to be the chosen umpire of his neighborhood; ever sagacious in counsel, judicious and sympathetic in consolation, and generous to aid; his long life extending over a century, and into the dawn of a new nation, with its fair promise of renown in story; this ancient man, with his tall, slender frame, and fine old features, reading his Bible in his lonely dwelling, is an interesting example of the ancient fathers of New England, whose memories are the most precious heir-looms possessed by their descendants.

Author's Notes - Chapter 1

*Baronetage, v., 556.

**See Macaulay, History of England, vol. iii., p. 123.

***See Appendix.

****This rests upon Master Sullivan's own family statement, to be found in the first Appendix. It is with him somewhat matter of conjecture. Colonel O'Sullivan joined the Prince soon after his arrival at Moidart; and was his quarter-master and adjutant-general, and military adviser before the Scotch leaders took exclusive control of his counsels. After the unfortunate battle of Culloden, he accompanied the Prince in his flight and concealment, and only left him, at his request, when the number of his followers rendered more precarious the Prince" chances of escape. This was shortly before the romantic adventure with Flora McDonald.

CHAPTER II. YOUTH AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES.

JAMES, the fourth son of Master Sullivan, was born on the farm at Berwick on the twenty-second of April, A.D. 1744. The cellar of the house occupied by his parents is easily distinguished by some portions of its walls still remaining in a field near Salmon Falls River, and within half a mile of the Great Falls village. The barn, which served to store away their harvests for the long winters of our New England climate, has only quite recently been destroyed by fire. Near by, but separated from the site of the old dwelling by a public road, laid out in comparatively modern times across the farm, is the ancient cemetery, where Master Sullivan and Margery his wife, when their long-protracted lives were over, were laid to their last repose, amid the scenes of their humble labors, and of the pleasures and various vicissitudes of more than half a century.

Few country places in New England possess greater variety of agreeable rural scenery than old Berwick; and the narrow, rocky defile, through which rushes the impetuous stream constituting its western boundary, and here separating the States of Maine and New Hampshire, has long been celebrated for its wild and picturesque beauty. Within a limit of four miles the Salmon Falls River, called by the Indians the Quampegan, wearing its away through walls of granite, which rise on either side in precipices or steep slopes clothed with vegetation, descends in rapid or cataract more than two hundred feet, before, making its last plunge at the village of South Berwick, it moves on, but with more quiet flow, towards the ocean. The vigorous rush of its waters has been long since brought into subjection by human power and contrivance, and applied to the purposes of utility; but a century ago, when the subject of our narrative wandered yet a lad about its shores, the stream poured through the dark primeval forest, undisturbed except by an occasional saw-mill, which, to his youthful taste, lent but another charm to the scene.

Berwick was then a frontier settlement; and not long before, one of its inhabitants, speaking of his dwelling, says there was no other house occupied by any white man between his own and Canada. The population, however, was gradually increasing, and the exasperation of the Indian tribes, as they marked the steady encroachment of the stranger on their hunting-grounds and most favored fisheries, was often manifested in stealthy attacks on some unguarded settlement, and by midnight massacre. Occasional retaliation served but to deepen further the spirit of resentment, and the annals of the period abound in revolting details of savage barbarity. Many a hearth was rendered desolate by the mysterious disappearance of child or parent, carried away by Indian war-parties to their distant villages. The inventive cruelty of our New England races quite equalled that recorded of any other people, and the captive rarely survived the agonies they took pleasure in inflicting amidst the brutalities of their fiendish festivals.

The Ossipees and other tribes, making their homes among the lakes and mountains of New Hampshire, had at times visited with hostile purpose the settlement at Berwick; and, for the better protection of the inhabitants from these incursions, numerous block-houses were erected at suitable places, to which they might retreat upon alarm. Master Sullivan and his sons were occasionally called upon to take part in their defence; and James, in his History of Maine, makes mention of having been himself in garrison at Gerrish's fort, west of Salmon Falls Brook. All the houses in the place were built of hewn logs sufficiently thick to resist musket-ball. The people went armed to the place of public worship, and watch was constantly kept from the steeple, three musket-shots fired in quick succession being the concerted signal of approaching danger. The inhabitants were generally engaged in agricultural pursuits; and the procurement of food, fuel and raiment, and security for themselves and their stock from the stealthy inroads of the savages and beasts of the forest, were the chief objects of their care and employment. Besides their military duties, -- and the people, having been well represented in the attack on Louisburg and in the French war, were partial to warlike exercises, -- they found ample occupation for their leisure in the sports of hunting and fishing, the woods swarming with moose and deer, and the streams with trout and salmon. The scenes and circumstances of early life have much to do with the development of character; and this slight sketch of the place where were passed his boyhood, and indeed the greater part of his first twenty years, will not be considered inappropriate in connection with our subject.

Belonging to a family which had been for many centuries engaged in military service, and this hereditary taste probably having the greater influence upon him from the stirring incidents of the wars so long waged during the middle of the last century between the French and English for supremacy on the American continent, Master Sullivan had secured for his eldest son, Benjamin, a post in the navy, and originally intended James for the career of a soldier.

These views entertained for the welfare of his children were not destined, however, to be realized altogether in accordance with his expectations; but he had every reason to be satisfied with their subsequent career. The vessel, indeed, to which Benjamin was attached, was lost at sea, before the Revolution, and all on board perished. But John, as one of the principal leaders of the American struggle for independence, will, in future times, there is reason to believe, be more highly estimated for his character and services, than heretofore by writers of its history. Daniel and Eben, his other sons, in a lower sphere of action gained distinction by their bravery, and were useful officers. James alone, for reasons shortly to be mentioned, was shut out from military employments; but, as will be seen in the sequel, he displayed in trying emergencies much ability and high military aptitudes.

With this plan for his future, James Sullivan pursued his studies under his father's direction. What constituted the family library, no means remain for ascertaining; but few books could have been accessible in a place so secluded. His education was, doubtless, more thorough in the branches attempted, than varied in character. As he grew older, the duties of the farm and the forest, and the constant watchfulness in which all participated to guard against the predatory forays of the Indians, afforded full occupation for his thoughts, and the best of discipline for his intellectual and physical faculties. His father was rather averse to labor in aught else but his literary pursuits; but Mrs. Sullivan was a woman of restless energy and strong good sense, and too ambitious for the welfare of her children to suffer her sons to be idle.

Few luxuries, or even what was indispensable to comfortable subsistence, could be procured without much toil, and, indeed, all were ever willingly at work. In the intervals of study, when his services were not required in farm-labor at home, James employed himself in boating on the Piscataqua, a broad river or arm of the sea, with the tide ebbing and flowing, and into which emptied Lamprey, Oyster Bay, and Salmon Falls Rivers. Lumber and other produce from the interior were floated down its tide to Portsmouth, in gondolas, long flat-bottomed boats, which could not, without both strength and much good management, be safely steered amidst its shoals and dangerous eddies. James soon became an accomplished boatman; and this life of hardship and exposure developed his muscles, and invigorated his character.

Two circumstances, at this period, exerting an important influence over James' future life, have been somewhat variously related. One warm day in summer, wearied with work, he had been sleeping on the grass, when, suddenly aroused, he beheld a large rattlesnake, coiled, erecting its head over him. Horror at the awful fate that impended, one familiar to our settlers in those days in the wilderness, gave a powerful shock to his system, and he fainted. The swoon probably saved his life; since, according to popular belief, the rattlesnake never strikes the sleeping, or those seemingly lifeless. He was ever after this subject to attacks of epilepsy, sometimes lasting for several hours, occurring often when on his circuits, and occasionally in court.

The other incident alluded to was the complicated fracture of one of his limbs while felling a small tree. His foot, while pressed upon a branch to secure better play for his axe, accidentally slipping, the bent tree sprang into place. James was thrown down, and his leg, caught in the cleft, was badly broken. The usual version of the story adds that, while thus prostrate, he cut his limb free with his axe, and, dragging himself along the ground to the stone-drag, contrived to work his way on to it, and drive the oxen home, the distance of a mile, to his father's house. This accident led to a long illness, and the consequence was lameness for life.

For two years he remained confined to the rural homestead. His medical attendant, of little experience or knowledge, managed to splinter the broken limb so unskilfully, that the cure, at last very imperfect, was greatly protracted. This confinement was not without its advantages; for, to beguile the tedious hours, his active mind became thoroughly acquainted with all the books he could procure. He devoted himself with great assiduity to the study of the Latin language, committing much of its grammar to memory, and reading with care the principal classics. This subsequently proved of essential benefit to him in his professional studies and literary labors. There was little to divert him from his pursuits. His elder brothers, as has ever been the case in New England, upon approaching manhood had quitted home to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Eben was a lad full of mischievous devices, and Mary, the only sister, was but a year older than Eben. One condition of the lease, already referred to, of the farm at Berwick, was that, as soon as James should be able to walk or ride, his brother John should take him home, "find him in food, washing, lodging and apparel, and instruct him in the art and science of the law." When qualified to take his oaths of admission to the bar, John was, furthermore, to supply him with the necessary books of forms and pleadings. The same instrument further stipulated that John should take charge also of Eben, and, when sufficiently advanced, provide for his education as a physician.

It is not intended to embrace in this memoir of James Sullivan the numerous interesting anecdotes of his elder brother, the revolutionary General, which, unrecorded in print, still float about New Hampshire. But, where the leading events of John's career have a direct bearing on the fortunes of James, some brief mention will be indispensable. Persevering in his sports, energetic in labor, ambitious and untiring in his studies, John had displayed from early youth much vigor of character. In a spirit of adventure he took, when a lad, to the sea; and, returning at the age of seventeen, determined, in all probability at the suggestion of his father, to devote himself to the law. There were but few lawyers then in the province, and these were looked upon as a superior order of society. It indicated much confidence in his power to command success, for a young man, without influential friends or collegiate advantages, to think of entering the lists. Still, he was not discouraged, and presented himself before Mr. Livermore, an eminent counsellor of Portsmouth, modestly preferring his request that he might be received as a student in his office, promising, as some return for the privilege, his services when required in labor on the farm or garden. Pleased with the good sense and appearance of his young visitor, Mr. Livermore yielded a ready assent to his proposal.

Improving every means for gaining knowledge and experience, John rapidly progressed; and his master, appreciating his talents, generously lent his aid to their development. On one occasion the lawyer was away from home when a client called for him to assume the defence, before a neighboring justice, of a cause which involved character and feeling, if no great amount of money. Disappointed at his absence, the client entreated John to undertake the case, who, as any delay would be fatal, consented with some reluctance.

At nightfall, Mr. Livermore returned home, and, learning how his pupil was employed, led by some curiosity to know how he would acquit himself, went to the trial. Wrapped in his cloak, and with his hat lowered over his face for concealment, he quietly observed, through an open door, the proceedings from an apartment adjoining the court-room. Great was his surprise. His student managed his witnesses with a shrewdness and good judgment that would have done honor to the most experienced practitioner; and, when his turn came to address the court, exhibited information, eloquence, and argumentative powers, auspicious not merely of future success, but distinction. Livermore did not choose to interrupt the joys of this first forensic victory; but the next morning expressed his gratification in no measured terms, assuring John that he should consider him thereafter as one of his own family, and gladly embrace every opportunity to find him employment and advance him in his profession.

Fired by this early triumph, and encouraged by this friendly sympathy, John Sullivan prosecuted his studies with renewed ardor. At the age of twenty he felt warranted to marry; and soon became widely known in New Hampshire as equal in talents and eloquence to any lawyer of its bar. He was endowed by nature with many requisites for professional superiority. According to his biographer, his person, though not tall, was well-proportioned and commanding. His complexion was dark, with a ruddy glow of health; his features handsome, with an expression dignified and full of animation. His eye was black and penetrating, his voice deep but melodious, and both promptly responsive alike to stern and gentle emotions. Reasoning faculties of a high order, perceptions rapid and distinct, and a ready imagination, with his warmth of temperament and quick sensibility, eminently qualified him for a popular orator. John Adams speaks at a later day of his fluency and wit when a member of the Continental Congress. Easily provoked, he was as easily appeased; and if his frankness and unreserve made him a few inveterate enemies, his general amiability of disposition and readiness to oblige secured him numerous friends, who were faithful throughout life. Lavish and open-handed by nature, the habits of country life admitted no expense, and his fees prudently invested made him rich. The friend of Governor Wentworth, who then held his court with some state at Portsmouth, the correspondent of Hutchinson, John Sullivan always took the liberal side in politics, and, by his able pen, and persuasive oratory, wherever men congregated to discuss affairs of state, did his best to induce resistance to parliamentary encroachments. Such was the teacher and guide of James Sullivan during those early years when his professional and political character was forming; when the heart is as wax to receive generous impressions, adamant to preserve them in their purity and strength.

About the period James entered his office as a student, John had removed from Newmarket to Durham, and, towards the close of the year 1764, purchased the handsome mansion erected by Dr. Samuel Adams, an eminent physician of the place, then recently deceased; and this continued to be his residence during the remainder of his life. The house still remains in good condition, and at the date of its erection must have been a more costly dwelling than was then usually to be found in country villages. The farm is beautifully situated, extending some distance along the shore of Oyster River, and in one corner of it, according to a custom then very general in that part of the country, upon an eminence of gentle elevation, commanding a most agreeable rural prospect, is a small private burial-place. Here, with his own family and those of his sister Mrs. Hardy and of his friend William Odiorne, all attached and intimate while living, General Sullivan was buried.

At the time of John's first settlement at Durham, a town rich in fertile farms, its inhabitants were devoted to the peaceable pursuits of rural life, and there prevailed among them a strong prejudice against lawyers. It was believed that they were a class not wanted in the community; that they fomented litigation for their own purposes, and craftily devoured the substance of their neighbors. Resolved, if possible, to secure their village from the presence of all such promoters of discord, some energetic young men gave the newly-settled counsellor notice to quit Durham, threatening personal coŰrcion if this peremptory order were not speedily obeyed. Nothing daunted by this open and decided show of hostility, John Sullivan informed them that he should not think of it; and, if they cared to resort to force, they would always find him ready. The people of the town became greatly excited, and took different sides in the quarrel; collisions occurred between the parties, and, in the progress of the dispute, one of the assailants was severely though not dangerously wounded by an over-zealous adherent of Mr. Sullivan. The affair already wore a serious aspect, when a truce was called, and it was finally determined to settle the question by a personal conflict with any combatant the assailants should select. Their chosen champion not being considered a fair match for the elder brother, who possessed great physical strength, James, at his own request, was substituted to do battle for the law. The encounter took place at the time appointed, and James came off the victor. The people, acquiescing in the result of this ordeal, ever after placed the greatest confidence in John Sullivan; and he soon became, and continued through life, their most beloved and popular citizen.

James applied himself, under his brother's guidance, with great zeal to the study of the law. If, from the limited advantages he had enjoyed at Berwick, his early education had been in some respects defective, his intellectual faculties had been well developed by the careful training of his father. He was endowed by nature with great vigor of mind, quickness of intelligence, and the power of steady application; and, with much to stimulate his ambition, and little to divert his attention in the circumstances around him, he made rapid progress.

The elementary course, from which the student of that period was compelled to procure his professional knowledge, was little more than Wood's Institutes and Coke on Littleton. Blackstone's Commentaries, dating a new era in legal learning, were published in London in 1765, but were not in general use on this side of the Atlantic until some years later. The limited number of books to be read was not unattended with advantage; for, with the powers concentrated on fewer subjects and authors, the mind of the student more easily possessed itself of what then constituted the whole science of the law. As both the elementary works and reports of cases in the colonies were from the old country, where the social condition, laws and usages, materially differed from those existing here, more thought was requisite in ascertaining distinctly the established principles from the precedents, and adjusting their application to questions arising in American practice. The mind of our student was admirably suited for his task. It was logical and philosophic; and he possessed that calm yet earnest intellectual disposition peculiarly adapted to grapple and fully comprehend the subtleties of his profession. His brother was already, fortunately for him, engaged in extensive practice; and this, whether in the simple disputes before the village tribunals, or in cases of greater magnitude before the county courts, was a better school for discipline than any reading however extensive or profound.

The period of his professional studies was likewise that of the Stamp Act excitement; and the gazettes of Boston and Portsmouth brought to the people of the interior full information of the state of feeling in the larger towns on the seaboard. The general discussion everywhere of the great principles of government, of our civil rights and obligation, was now preparing the public mind for the subsequent struggle. It can be easily imagined that these important lessons were not thrown away upon a young man of generous and ardent aspirations, possessing an hereditary detestation of arbitrary power, transmitted in his veins from progenitors who for centuries had battled against it in Ireland.

While at Durham he was a frequent visitor at the house of William Odiorne, which stood, and still remains, near that of General Sullivan. Mr. Odiorne, a ship-builder, and also a commissioner, under the royal government, for the preservation of the forests in New Hampshire, was the son of Jotham Odiorne, born in 1675, and who died in 1748, one of the Judges of the Superior Court of the colony. Mrs. William Odiorne was Avis, daughter of Dr. Hugh Adams,* a celebrated and very eccentric clergyman, long settled at Durham over the Oyster Bay Parish, and a brother of Matthew Adams, the early friend of Dr. Franklin. In the New Hampshire Historical Collections may be found many amusing particulars of Dr. Hugh Adams, who possessed great wit and learning, but often provoked the animadversions of his brother clergymen, as also of some of the graver and more simple members of his parish, by an independence of opinion which occasionally somewhat scandalized their orthodoxy. He continued his pastoral charge of the parish at Durham from the year 1718 to 1739, and died there in 1750, at the age of seventy-four. He was a graduate of Harvard, of the class of 1697.

The family of Mr. Odiorne was numerous, and consisted in part of daughters just on the verge of womanhood. One of them, named Hetty, was peculiarly pleasing in the eyes of James Sullivan. He wooed and won, and soon became her accepted lover; although, from prudential considerations, their marriage was deferred for a year or two, until his success at the bar should justify their union. Born June 26, 1748, she was four years younger than her betrothed.

Author's note - Chapter 2

*It is recorded, and may be interesting to some of her numerous descendants to know, that the maiden name of the wife of Dr. Hugh Adams was Susanna Winborn.

From pp. 84-86 - On Master Sullivan's son, Ebenezer.

Eben, the younger brother of James, now twenty-three years of age, as captain of a company raised in Berwick, of which Nathan Lord was lieutenant, had been present at the battle of Bunker Hill, and afterwards went with the expedition into Canada. In May he was sent by General Arnold from Montreal, with Major Sherburne, who had under his command one hundred and forty men, to relieve Major Butterfield, who, with a force of four hundred, was in garrison at the Cedars, a small fort forty-five miles to the south-west. The route was difficult; and, though they left the camp on the sixteenth, four days later they were still nine miles from their destination. Not learning that Major Butterfield had surrendered the day before, Major Sherburne started at noon on the twentieth with one hundred men, the rest having been left on the way; and, after marching five miles through the woods, they were attacked, in open ground, without shelter, by one hundred Canadians and four hundred Indians. After an unequal contest of one hour and forty minutes, in which they contrived to kill twenty-two of the enemy, of whom one was a principal chief of the Senecas, with the loss of twenty-eight of their own number, they were surrounded and overpowered, the savages running in and disarming them. They were stripped, some of the party slain in cold blood, and the others driven to the fort, which was now in command of a British officer, Captain Foster. Major Sherburne and the officers were sent to Connesedago, near the Lake of the Two Mountains; the privates taken to an island, where they were kept for eight days without clothing, and exposed to the weather. General Arnold entered into an agreement with Foster for an equal exchange of prisoners within two months; and Captains Sullivan and Bliss, of Sherburne's party, and Captains Stephens and Green, of Butterfield's, volunteered as hostages for the faithful performance of the conditions.

Eben was carried into the forests by the Indians, and remained some time their prisoner. On one occasion, while he was seated with them round the fire, over which was suspended a caldron containing their dinner, one of the Indians grossly insulted him; whereupon, being of quick temper, and heedless of consequences, he seized the ladle and flung some of the hot broth over his assailant. The savages immediately seized and pinioned him, and, tying him to a stake, piled about it fagots, which they were in the act of kindling to roast him alive, when, fortunately for their intended victim, an English officer entered their camp. His earnest expostulations arrested their proceedings, and Eben was spared, as he had reason to suppose, for an equally cruel death at a future day. Many weeks passed on, during which he was subjected to various tortures, ingeniously devised to shake his firmness, and led again to the stake, with the professed design, not, however, put in execution, of giving him to the flames. Knowing enough of Indian character and habits to realize that his safety depended in submitting without fear or flinching to these trials of his endurance, he bore them all with heroic fortitude.

The compact of Foster and Arnold was not carried out, and remained long a subject of controversy, the English general refusing to sanction the terms agreed upon. When Captain Sullivan obtained knowledge of this refusal to comply with the stipulations for which he had made himself a hostage, feeling that the conduct of the savages towards him had been contrary to all rules of civilized warfare, he concluded he was under no further obligation to remain. Watching his opportunity, when the Indians, on some festive occasion, after their games, dances and carouse, had sunk at night into profound slumber, and the two sentinels, cheated out of their vigilance by his pretended sleep, were taking their repose, he glided silently out of the camp, and made for the bank of a neighboring river, in order to swim across to a Dutch settlement which he knew to be on the opposite shore. The shout of his pursuers was heard as he entered the water, and, when near the middle of the stream, the plash of their dog, a large and ferocious animal, as it entered the river. He turned, and, as the dog approached, managed with one hand, while he supported himself with the other, to press its bead beneath the surface, and, having drowned it, to effect his escape. Some days later, fearing that, having volunteered as a hostage, his honor might be implicated by his flight, he surrendered himself to a British officer, and was taken to Montreal. It was many months before his exchange could be effected, so as to admit of his resuming active service, much to his chagrin, as shown by various letters of his in print. We find him, however, in 1778, aid of his brother, the general, in the Rhode Island campaign.

No apology seems needed for this long digression from our immediate subject. Judge Sullivan was affectionately attached to his brothers, and his solicitude that they should acquit themselves honorably in the contest, and his lively interest in the various vicissitudes which befell them in its course, is abundantly manifest by what little remains of his correspondence at this period. Their services and sufferings undoubtedly served in some measure to increase his own hold upon the esteem and affection of his countrymen.

From pp. 121-2, on Master Sullivan's sons, Daniel and John.

|

|

|

Benson J. Lossing. General John Sullivan is on the right. |

Before closing this account of the period Judge Sullivan passed upon the bench, it may not be uninteresting to record some incidents in the life of his elder brother, Daniel, who fell at this time a victim to the barbarous cruelties, the privations, famine and disease, of the British prison-ships at New York, called the Jersey hulks. He had established himself, about 1765, on the upper end of Frenchman's Bay, at a place now flourishing as the town of Sullivan, and, engaging in the manufacture of lumber, erected two sawmills. When the revolutionary war broke out the machinery was removed, and the buildings burnt; a visit from the enemy being apprehended, as Daniel, in common with his other brothers, sided warmly with the patriots. He held a commission as a captain of minute-men, and was present with his company at the siege of Castine, in 1779, in which the militia of the neighborhood acted in concert with the troops under Solomon Lovell, and the fleet commanded by Richard Saltonstall. The attempt on Castine not proving successful, Captain Sullivan returned home with his men, keeping them always in readiness for action. His zeal and activity made him a marked man to the English and the tories of the vicinity, who had several times ineffectually endeavored to capture him. These attempts had failed, in consequence of the vigilance observed by the patriots, till one fatal night in February, 1781, when there was reason to suppose, from the severity of the weather, that no one would venture abroad, an English ship, the Allegiance, anchored below the town, and landed a large force of sailors and marines. The house was silently invested, and Captain Sullivan, aroused from his slumbers, found his bed surrounded by armed men. He was hurried to the boat, and his dwelling fired so suddenly that the children were with difficulty saved by their mother and the hired man living in the family. Taken to Castine, his liberty and further protection from harm were tendered him on condition he took the oath of allegiance to the king. Rejecting these proposals, he was carried prisoner to New York, and confined in that dreadful hulk, the Jersey prison-ship. Here the pestilence, engendered by confinement and starvation, and the tender mercies of Provost Cunningham, did their work, and he died in April, 1782.General Sullivan, after his successful expedition into the western country, in the summer of 1779, had found his health so far impaired by the exposures and hardships of five years, incessant military service, as to feel compelled to retire from the army. He received, upon retiring, the thanks of Congress, and the most generous testimonials of affection and esteem from General Washington. He was, immediately after his resignation, sent to Congress from New Hampshire. His constant employment upon the most delicate and responsible duties, as shown by its journal, evinces the respect of that body for his character, ability and public services. He was for the rest of his life, with but slight intervals, in distinguished positions of public duty in New Hampshire. At the commencement of the university at Cambridge following his withdrawal from the army, honorary degrees were bestowed both on him and his brother James.

Master Sullivan of Berwick, father of James, when far advanced in years, wrote out the following statement of his family and origin, at the request of the wife of his son, General John Sullivan: "I am the son of Major Philip O'Sullivan, of Ardea, in the county of Kerry. His father was Owen O'Sullivan, original descendant from the second son of Daniel O'Sullivan, called lord of Bearehaven. He married Mary, daughter of Colonel Owen McSweeney of Musgrey, and sister to Captain Edmond McSweeney, a noted man for anecdotes and witty sayings. I have heard that my grandfather had four countesses for his mother and grandmothers. How true it was, or who they were, I know not. My father died of an ulcer raised in his breast, occasioned by a wound he received in France, in a duel with a French officer. They were all a short-lived family; they either died in their bloom, or went out of the country. I never heard that any of the men-kind arrived at sixty, and do not remember but one alive when I left home. My mother's name was Joan McCarthy, daughter of Dermod McCarthy, of Killoween. She had three brothers and one sister. Her mother's name I forget, but that she was daughter to McCarthy Reagh, of Carbery. Her oldest brother, Col. Florence, alias McFinnin, and his two brothers, Captain Charles and Captain Owen, went in the defence of the nation against Orange. Owen was killed in the battle of Aughrim. Florence had a son, who retains the title of McFinnin. Charles I just remember. He had a charge of powder in his face at the siege of Cork. He left two sons, Derby and Owen. Derby married with Ellena Sullivan, of the Sullivans of Bannane. His brother Owen married Honora Mahony, daughter of Dennis Mahony, of Drommore, in the barony of Dunkerron, and also died in the prime of life, much lamented. They were short-lived on both sides; but the brevity of their lives, to my great grief and sorrow, is added to the length of mine. My mother's sister was married to Dermod, eldest son of Daniel O'Sullivan, lord of Dunkerron. Her son Cornelius, as I understand, was with the Pretender in Scotland, in the year 1745. This is all that I can say about my origin; but shall conclude with a Latin sentence:

'Si Adam sit pater cunetorum, mater et Eva;

Cur non sunt homines nobilitate pares?

Non pater aut mater dant nobis nobilitatem;

Sed moribus et vita nobilitatur homo.'&nb sp; "J. S."

The following letter is that referred to in the text as written in Ireland the day Master Sullivan died at Berwick, in Maine: "A grand-uncle of mine having gone to America about sixty years ago, his relations have suffered greatly from being without the means of finding out his fate, till now that by great good fortune I am informed you are a son of his. If you find by the under account that I have not been misinformed, I shall be glad to hear from you.

"I am, sir, yours respectfully,

"PHILIP O'SULLIVAN.

"Ardea, May 16th, 1796."

"Mr. Owen O'Sullivan, son of Major Philip O'Sullivan, of Ardea, county of Kerry, Ireland, by Joanna, the daughter of Derby McCarthy, of Killoween, Esq., in said county. They were connected with the most respectable families in the province of Munster, particularly the Count of Bearehaven, McCarthy More, Earl of Clancare, Earl Barrymore, the Earl of Thomond, the Earl of Clencarthy, McFinnin of Glanarough, O'Donoughu of Ross, and O'Donoughu of Glynn, McCarthy of Carbery, and O'Donovan, &c."

Related to The Tory Lover