Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

PEG'S LITTLE CHAIR.

Miss Margaret Benning told me this story about her childhood, and I am going to tell it to you, though you will miss a great part of the pleasure of it unless you can shut your eyes and imagine just how she used to look; a small, bright-eyed old lady, who sat as straight in her old-fashioned chair as I hope you sit in yours, beside a pleasant south window with a pink geranium and a white petunia and a large scarlet horseshoe geranium blooming on the sill. Her fingers were stiff and bent, but they were always busy, and her kind blue eyes saw many things that other people's miss. Dr. Holmes said once in a birthday letter that his friend Mrs. Julia Ward Howe, was seventy years young, and this would have been true of my friend Miss Margaret Benning. I wish that every boy and girl had just such a wise, dear old lady to tell them charming stories about old times, and to be just as much interested beside in their own new times.

"Yes, dear," said Miss Margaret decidedly, taking her foot out of the quaint little chair which she had been using for a foot-stool. "Yes, dear, I always thought everything of that chair."

She pushed it toward me so that I could see it the better, though I knew well the look of its prim back and round wooden seat and how strong and sturdy it was on its four short legs.

"It was a chair," she continued, "that belonged first to a great-aunt of mine when she was a little girl, and then it came to my mother when she was big enough to sit up straight out of a lap, and then mother gave it to me. It's an old little chair for the size of it and about as much use to me now as 'twas when I first remember it. I couldn't keep house without it, especially now that the rheumatism's got into my foot and I have to keep it up from the floor.

"Mother had four children older than I, but she never gave the chair to any of them until I came along and was named for her. I look like her, people say, but I don't know that there are many persons about here now that remember mother. I feel some days as if there weren't a great many that remembered me; everybody's died or moved away, and there are few left of the old stock. Mother and I always loved to be together as long ago as I can remember; she always knew what I wanted before I spoke; one of the gentle kind she was, that a good many folks push right by. Those loved her that knew her.

"She understood, I'm sure, how we belonged together, but just because she loved me different she used to whip me the most. Partly because I needed it, but partly because others were always ready to say she was partial to me, and favored little Peg above the rest (that was me, you know, dear).

"I know well the very day when she first said I could have the chair for mine. I was so small I left it out over night in the rain with my dolls settin' in it and the bran-filled one, that I loved the best, all leaked away. The Dutch doll weathered the exposure an' I've got her now. I let the children play with her that come to see me, but her joints don't work as they were made to; the rain that night warped my Dutch doll. Grandpa Henderson brought her home from the Hague. I remember his pulling her out of his great-coat pocket when he came ashore from the ship.

"Grandma Henderson was 'the captain ashore' he always said. Grandma liked my sister best because Hannah was named for her, and as for the boys, why, they weren't anybody's favorites; they used to be always stretching themselves up beside the barn door, for they had the promise of going to sea when they'd grown enough; they herded together, the boys did, and were a wild pack when they were little, though they were good hands to work and biddable boys about waiting and tending.

"Mother was left a widow just after I was born. Father was lost at sea, and then though Grandpa had left the sea himself he just went back again to get something to bring us up with. He and father owned a good part of the ship between them, and I suppose he thought 'twas best to see after his property, and any ways he never was a man to be contented ashore. Grandma kept public house; there were a great many travelers on the upper post-road where we lived and the house was big and pleasant and when anybody stopped there once they were glad to come again. Grandma and mother and old Sally did everything themselves, and Grandma treated everybody as her own company and made them comfortable and acted as if the roughest of 'em had come to make a visit and were her own relations. And I've seen teamsters and sailors just ashore, and old General Dunn and two members of Congress all at the table together and every one of 'em as good-mannered as he knew how.

"I thought 'twas a great honor when I was called big enough to wait, and mother kept me at her left hand when she headed the table and told me what to do to help along. Sister Hannah was Grandma's waiter, and old Sally, she kept things straight in the kitchen. But when Grandma and Hannah were in the dining-room mother and I were out. 'Twas a good house, everybody said. Old Judge Forrester said that he never enjoyed a visit so much the year round as he did when he stopped going and coming from court in Boston.

"Oh, it was a splendid place. I wish you had seen it in its prime," said Mss Margaret. "You'd never know it now with that French roof on top and all the elms gone -- and the nice old windows pulled out - but listen! When you go down street I want you to just look at the big horse block and see how high 'tis. They've pulled the house all to pieces inside too; the old fire-place's got a range bricked into it. I'll warrant you never got one o' mother's batter puddings, nor a cut of old Sally's prime loaf cake.

"I could tell you what we used to set on the table for a good dinner and 'twould make you feel hungry for a week. Everything of the best. None of your baking-powder cake that ain't even sweetened, and none of your soup that's bought in tin cans, or your chickens raised by machinery. The boys, they had a great hen-coop, but after all 'twas Grandma who oversaw all those things. Grandpa used to fetch home big cheeses and other stores from England and Holland - such standbys as were scarce here and once when he was direct from the East Indies he had a whole cartload of the best of sweetmeats and tea, and so nobody ever lacked good living that stopped with us. Mother and Grandma both shortened their valuable lives, and went off with apoplexies, but we young ones all seemed to flourish and all of us live to good ages except Jonas, my next oldest brother but one, and he was lost at sea, which might or might not have come of high living; we never knew the particulars.

"There were no over-heated houses then, and nobody dressed too warm; 'twas mostly good eating that kept folks a little above freezing point. You got warm from the inside out instead of from outside in, and 'twas a more natural way, and women were busy and stirring about their houses themselves, and every child was kept a-hopping and made to work.

"Now I'm getting round to telling you about that chair: 'Peg's little chair' everybody took to calling it, for the chair and I about lived together. If I was called to shell peas I couldn't set on the doorstep same 's other folks, but I'd have to settle myself in that, and there I put my shoes stockings on in the morning and there I knelt down buzzing with sleep and said my little prayers at night, and I used to have to step on it to climb up into my mother's big four-poster bed. Grandma, she took sister Hannah, and we were all together in the long east chamber when Grandpa was gone to sea, so Hannah and I could talk nights before the old folks came up.

"'Twas pleasant at the old place. There was a good deal of the time we were as quiet as any family, but you never knew when folks were going to rattle into the yard and want everything in a minute, and Black Sally would begin to give orders to Hannah and me, and then run across the yard to kill a fowl for breakfast and have it all picked and hung up before it knew its head was off.

"You see the house had once belonged to a rich old Tory who had to run in war time, and he'd lived in great state and was some kind of a king's officer, and the dining-room used to be thirty-six feet long before they cut it in two as it is now. That was why, if there was a great public occasion going forward, they were pretty sure to come to Grandma, for she could set two tables the whole length, and provide according. There wa'n't such a room within ten miles that I know of, and perhaps twenty.

"It's a good while ago now, but I remember as well as yesterday when General Dunn and old Mr. Pomeroy came riding into the yard with their red-lined shoulder cloaks a-flying back and told Grandpa that General Lafayette and his friends were coming next day but one by the upper post-road and would get here about nine o'clock and meant to stop to dinner.

"'I shall give my old friend a glass of wine at my house,' said General Dunn, very dignified and slow; 'but there is no place so appropriate for an entertainment of the ladies and gentlemen of the neighborhood as your fine room and nobody is more able to provide a fine table than you, Mrs. Henderson. I will furnish the wines that are needed, and you shall be amply remunerated.'

"Grandma bowed and said her say and the gentlemen rode off in a hurry, for they had a great deal to do about their arrangements, the news having come so late. Grandma had been complaining of the rheumatism that morning and old Sally had her face tied up for the toothache, but off came her green handkerchief and you could hear the last squawks of fowl after fowl before you could get your breath. Why, the whole flock o' chickens used to try to escape her; go under the long barn; up in the apple-trees, anywhere they could if Sally so much as crossed the yard with her clean homespun on late in the afternoon. When she'd go an' come from meeting in her good bunnit, it seemed as if they'd have fits. And that day Hannah and me were set to chopping and pounding spices, and beating eggs. There never was such a scratchin' round any day I can remember, though there was always a great stir when Grandpa's ship was in an' he was expected.

"Grandma and mother both said we must all do the most we could to honor the nation's guest. Hannah was usually very knowing to things, being two years and some months older than I, but when we were getting more raisins to stone in the big locked pantry, and I says, 'Hannah, what makes him the nation's guest?' she couldn't exactly tell and was obliged to say right out she didn't know.

"Not but what we were used to hearing the name o' Lafayette. For our folks remembered the old war and his coming over from France to fight, but we were only little girls seven and nine or thereabouts, and I was none too big to sit in my little chair.

"My! how Grandma bustled about that day! I don't feel sure that she went to bed that night, for somebody must have set up to watch the two brick ovens. 'Take that chair out o' my tracks,' she kept a-saying; for I kept setting it down anywhere and straying off. At last she said she should certainly break her neck over it, and gave me a pair o' sound boxed ears, and so I took my chair and lugged it off, but with kind of hurted feelings I well remember, bein' a willin' child, but not strong and I may say tearful by spells in those days. The chair and me companioned one another so much that I begun to think it knew everything I did. I ain't sure it don't!

"I was saying that I took the chair and my citron to slice and went and sat out in the front doorway where it seemed still an' pleasant. Some o' the neighbors had to come an' help us that day an' the next, but Grandma and mother both said they never knew the brick ovens to bake evener, and everything turned out of the best so that, an hour before there was any need of 'em, the two long tables were set forth loaded, and there never were two such tables in this place before or since, at least that is my best belief.

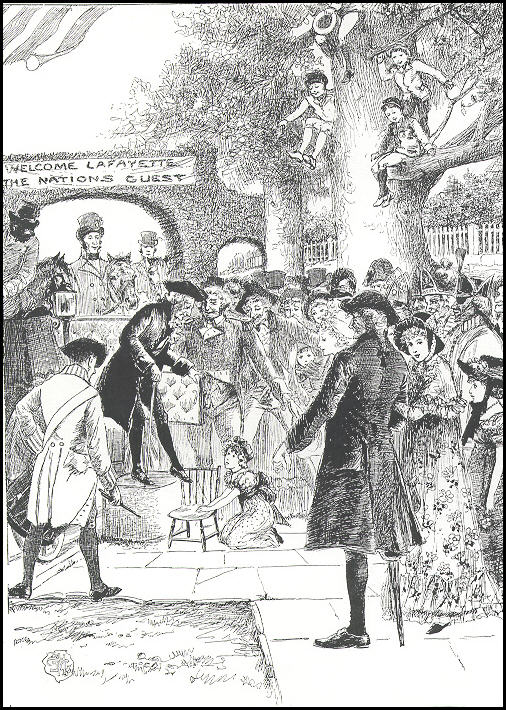

"They had got up as good a reception

as they could for such a little scattered place and at such

short notice, but everybody said 'twas nothing to be ashamed of.

There was a great archway over the post-road covered with

evergreen boughs and all the ladies in town made paper flowers

and rosettes of all colors to fasten among the evergreen. It did

look lovely and there was 'Welcome, Lafayette, the Nation's

Guest' on it in big letters, and all the children, were standing

in rows on the roadside and every one had a badge of white satin

ribbon, printed with his picture and 'Welcome, Lafayette,' and

when he rode by all the girls were to curtesy and the boys to

bow and we had to sing a piece, but only precious few knew any

of the words. I remember them now and the tune, too, but I shall

have to say them to you, for my voice isn't what it used to be.

I keep all the airs I used to know clear in my mind, though, and

think 'em over when I sit here alone. This was the way the Lafayette song was worded:

"'The Fathers in Glory shall sleep

That gathered with thee to the fight,

But the sons will eternally keep

The tablet of gratitude bright.

We bow not the neck

And we bend not the

knee,

But our hearts, Lafayette,

We surrender to

thee.'

"They told us we must first say 'Welcome, Lafayette' all together as he drew near, and then strike up the song and keep a straight line like soldiers, but 'twas so long to wait that we got playing and the wild ones would stray off until somebody would call out 'Coming!' to toll them back.

"For there we had all been posted by half-past eight, and waited and waited, for those who lived in the next towns kept delaying the procession so that 'twas near eleven when we heard the fifers and drummers coming over the hills. I had on my best shoes of course and they were most new and pinched my poor little feet, so when Lafayette did appear at last I was thankful, though I held out to sing good and loud and he made us an elegant bow and accepted a bouquet from General Dunn's little granddaughter who stood at the end of the line.

"He was beautiful looking, and it all came to my mind what I had heard people say about his leaving his good home to come and help us fight for liberty. I felt as if my father, that I never saw, would be smiling and kind like that, and I burst out a-crying while I tried to sing 'The Fathers in Glory,' being overwrought I dare say, and my best shoes being tight, but I sang right on with the tears a-rolling down, and Hannah said when the fifers and drummers and the gentlemen in sashes riding ahead and the general's coach and four white horses had all got by, 'Cut and run now,' says she. 'Here, Peg, take hold of my hand.' And so home we went as we were bid, to pick flowers to dress the cakes, and to finish breaking up a sugar loaf that we couldn't finish in the early morning.

"We had all been up before day and there wasn't anybody who ever worked so hard before except old Baptist, who was always idle whatever went on; a queer old foreigner he was that had fought in the Revolutionary War and got hurt in his head. He had lived with Grandma in years past and was handy in a good many ways, but in my time he used to wander about the country, and was very strange acting, but harmless. I know he used to come along the road every little while and say good-by to all of us because he was going home to France. You couldn't understand much that he said, but folks respected him, and he used to sleep in barns in the summer and then get his breakfast and travel along. He was a great hand for being round on training days, and so that day we weren't surprised to see him appear. Mother gave him a good bowl of soup and Grandma cut him some new bread that he liked, and told him not to get hurt, I remember, and to keep away from the crowd, but he hung round the house and sat out on the horse-block, and was a-counting over some pieces of stones he took out o' his pocket in a bag as if they was money.

"After I finished all that Grandma and mother had set me to do, mother kissed me and said I was a good girl and I might go and rest me until the folks came. 'Here's Peg's little chair underfoot as usual,' says Grandma again just then, and I took it and lugged it right along. My little legs ached under me, I'd stood so long, besides fetching and carrying since the break of day.

"There were ladies and gentlemen waiting in the best room and some of them called to me to come in as I was passing the door, so I went in and made my manners. As I look back I do believe this chair was same as other children's dolls to me. The ladies laughed at it and somebody offered me a dollar if I would sell it and little they knew how much it was worth, though but a common little homemade thing to their eyes.

"Just then mother stepped to the door and said that the General was just starting to come over from General Dunn's, and I started for the yard you may be sure, chair and all as usual; to tell the truth I knew if we got in Grandma's way again she'd order us off up garret.

"I got close to the great high horse-block just as the four horses and the General's carriage came up and when I saw General Lafayette again, child as I was, my heart came up in my throat, and I'd have just laid down and died if 'twould have done him any good. The grown folks all felt just the same; it seemed to me the crowd was twice as big as it was at first down by the arch.

"Then General Dunn opened the carriage door and Lafayette stepped out, and all the veterans of the Revolutionary War were drawn up in line, and some had lost a leg or an arm or wore big green patches over their eyes, but every one was there that could be moved unless it was Baptist, and they all saluted Lafayette and he saluted them, and two that fought under him came forward and spoke of it - oh! there ain't such scenes in these days and I was right there in the press, underfoot as you might say, and they called the names of the battles they'd been in, and the folks that stood round cheered and cheered till they were hoarse.

"It comes to my mind as plain as if I stood there again. The General was a lame old gentleman and walked with a cane and when there was a chance for him to go into the house he stood still and looked down from the old horse-block as if it was too long a step for him and he didn't know just what to do.

"Two or three shouted fer something to be brought, but they didn't see me and my stout little chair, and I set it for him and got down on my knees and held it steady for him with my two hands, and Lafayette stepped down into it and on to the ground just as nice as could be.

"Some of the people saw it and laughed, and some began to hurrah, and I felt burning red and as if every strange eye was on me, and I couldn't see plain which way to run because my eyes got brimful of tears, I hung my head over and that good old man laid his hand right a-top of it.

"'God bless you, my child,' says he; and then he felt in his waistcoat pocket and found a silver ninepence and put it into my hand and shut my fingers over it. Oh, I was so pleased I couldn't help holding my face right up to kiss him, and he kissed me, too, as kind as could be. 'Twasn't my nature to be forthputting, I was commonly very shy with strangers, but you see that I was nothing but a little thing, and I expect he was pleased to have me handy with the chair.

"Then all the ladies and gentlemen went into the house to their great dinner, and I had to run after them and tend to my duty. I was afraid Grandma would think I was behindhand, but somebody had told her about the chair and she appeared pleased and said I really had some thought about me for a child, and I'd have to keep my little chair in a glass case. She wished I would, she said, laughing, and I ran away and tucked it into a safe corner until the people had gone.

"They sat a long time at dinner and drank toasts and made speeches, and the boys and some grown folks, too, peeped in at the doors and windows and Grandma kept scolding and saying 'twan't proper - but if they were told to go off they'd come right back again, like flies.

"Oh, 'twas a great day! There's nobody left alive now that sat down at that table; all the grand folks in their uniforms and their silks and satins got old and gray, same as I be now, and they all went one after another, and to some there are tombstones and to others none. They all said they never saw a handsomer dinner, and other entertainments were compared with it a great many years afterwards. Everybody ate with a great appetite, but Hannah and the boys and me were most a week finishing up the cakes and fancy things that would spoil. Hannah had a fever turn out of 'em, but I weathered through for all I was thought to be a feeble child in those days.

"So there's all of that story," said Miss Margaret. "You can tell everybody that you have seen my little chair that Lafayette stepped his honored foot in." She clasped her hands in her lap and looked out of the window as if her thoughts were still busy with the events of that great day.

"Oh, I nearly forgot about Baptist," she exclaimed suddenly. "That's something you'd like to hear. Baptist was having one of his dazed, queer times, and Grandma tried to have him go and sleep it off somewhere, on the hay or up garret; 'twas the wound in his head that troubled him. He seemed to know that something great was going on that concerned him, and by and by when we weren't looking he got to the dining-room door, and then he gave a great cry and before folks could stop him, he was in the room jabbering French as if the last of his shaky wits were gone. He tumbled right down in front of Lafayette and caught him about his knees and when they tried to get him away and the other officers didn't know what to make of him the old general waved 'em back, and bent over and talked French and then looked queer and sharp at Baptist's face, and what did they do right before the folks but kiss each other on both cheeks, and poor Baptist cried hard as he could and Lafayette had to wipe his own eyes more than once. He and Baptist had played together in France when they were boys, and Baptist came out with some of the French officers. He was thought to be dead by those who knew him, so I've understood since, and I don't know just how it was that he strayed here though I suppose I've been told. He never had learned much English any way, though he was clever to work and but for being shot in the head would have been quite a man

"Lafayette left the table and came out to the front door with him, talking very quiet and kind and patting him on the shoulder, and gave him some money and told General Dunn to take kind care of him. They said he left some money with the General and meant to make inquiries for Baptist's relations when he got back to France, but poor old Baptist didn't live a great while after that. Grandma and mother kept him at the house after he began to fail, and nursed him as kind as they could.

"I remember I used to take this little chair and my stent an' go an' sit with him. I would sew or knit and sing my little pieces to him, and one day he was all right in his head and he began and told me a great long story -- he supposed I understood it, but 'twas all in French. I used to sing over and over the one they taught us when we stood in line to welcome Lafayette. He forgot all his English before he died and used to tell things in French to my grandmother, and be so eager about it and she would nod her head and say yes, and she never let him want for anything.

"Mother said I must learn French by and by when I went to school at the Academy, so if a stranger should be in distress again where I was. I could help him out, and I always do wish I knew how to talk French when I think of poor Baptist, and how bad we felt not to understand him, but it's too late now," said Miss Margaret soberly.

Presently she turned and pulled out the lower drawer of her work table and found a little round box with a painted glass top. She held it for me to look at, and I heard something chink, but she did not let it go out of her hand.

"There is the ninepence," she said, and I could indeed, with great respect, look at the long-treasured Lafayette ninepence. The little chair stood there beside us, and appeared as if it were sound and sturdy enough to last as long again as it had lived already. Miss Margaret looked at it with affection, as if it really remembered as much as she did. Old and new things have quite different values to persons of her age, but it was evident that she felt young again when she though of her childhood and of the great day of Lafayette's coming.

"You can tell every body now that you've seen the little chair he stepped in," she repeated.

"And the little Peg whom he kissed,"

said I.

Illustrations for "Peg's Little Chair" by Sarah Orne Jewett

Edmund H. Garrett (1853-1929) was a painter, illustrator, and etcher. He studied at the Academie Julien in Paris; was a pupil of Jean Paul Laurens, Boulanger and Lefebvre, Paris. He won a medal in Boston, 1890, and exhibited at the Paris Salon and principal exhibitions in America.

H. Dudley Murphy (1867-?) was a painter, illustrator, etcher,

craftsman, and teacher. Murphy studied at the Boston Museum

School and with J. P. Laurens in Paris. He won several medals

for portraits, oil painting, and watercolors. His art is

featured in several museums, and he was an instructor in drawing

and a member of the Faculty of Architecture at Harvard

University. (Source: Mantle Fielding's; Research: Chris

Butler).

The first illustration appears to be by H. D. Murphy.

The second illustration is titled "Peg places her little chair

at the service of Lafayette."

It is initialed by Edmund H. Garrett.

"Peg's Little Chair" appeared in Wide

Awake (33:204-214) in August 1891, with illustrations by

Edmund H. Garrett and H. D. Murphy. Not collected in Jewett's

lifetime, it was later included in Richard Cary's Uncollected

Stories of Sarah Orne Jewett. This text is from Wide

Awake.

In a letter to Annie Adams Fields of

August 1891, Jewett wrote: "Did you tell poor little Katharine

Foote that my Wide Awake story is true? It isnt except the fact

of my having having the little chair -- I made up every bit of

the story about it because I thought the dear thing ought to

have a story! It belonged to my grandmother but I think it may

have been her grandmothers before her! it has always been here

in the house and nobody knows any more about it -- but I love it

a good deal."

[ Back ]

Miss Margaret Benning: The

Marquis and Marquise de Lafayette visited Berwick in 1825.

Jewett mentions his visit to Mrs. Cushing in "The Old Town of

Berwick." Presumably, Jewett is drawing upon this almost

legendary event in her home town for elements of this story.

However, it also is possible that Miss Margaret Benning was a

real person and the source of this story. Further information is

welcome.

[ Back ]

horseshoe geranium: Pelargonium

Zonale; this red or white flower blooms from early spring

through autumn, and is native to Australia. (Research: Chris

Butler).

[ Back ]

Dr. Holmes: Oliver Wendell

Holmes (1809-1894) was a poet and author of The Autocrat of

the Breakfast-Table (1858). Trained as a physician, he was

the father of the Supreme Court Justice, Oliver W. Holmes, Jr.

[ Back ]

Mrs. Julia Ward Howe: Julia Ward

Howe (1819-1910) was a poet, lecturer, abolitionist, and

activist for woman suffrage. Perhaps her best known poem is "The

Battle Hymn of the Republic" (1862).

[ Back ]

the Dutch doll: A jointed

wooden doll. (Research: Chris Butler).

[ Back ]

French roof: It seems most

likely from the context that a gambrel is meant, rather than a

French dormer. (Research assistance: Chris Butler).

[ Back ]

batter puddings: a batter

pudding is likely to be what is usually meant by a pudding

today, a sweet dish made from cooked flour, sugar, and milk or

water.

[ Back ]

Tory who had run in war time: In the

American Revolution, Tories remained loyal to Great Britain.

Some were forced to flee the colonies by their rebel neighbors.

Jewett wrote about such an incident in her novel, The Tory

Lover, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1901.

[ Back ]

General Lafayette and his

friends were coming: The French Marquis de Lafayette

(1757-1834) was an enormously popular hero in the United States

after his participation in the American Revolution of 1776. The

Marquis and Marquise de Lafayette made a grand tour of the

United States in 1825. See two accounts of the 1825 visit

by General Lafayette to Madam Cushing in South Berwick and

the Charles Cushing Hobbs Talk.

[ Back ]

raisins to stone: these dried

grapes were not seedless; hence before serving them the seeds

(stones) had to be removed.

[ Back ]

the Lafayette song: I have not

been able to verify that such a song was sung to welcome

Lafayette during his visit to the United States, though other

sources indicate that he was greeted at some points by original

songs in his honor. Further information would be welcomed.

[ Back ]

a silver ninepence: The ARTFL

1913 Webster's dictionary offers two definitions: "1) An old

English silver coin, worth nine pence. 2) A New England name for

the Spanish real, a coin formerly current in the United States,

as valued at twelve and a half cents." (Research: Chris Butler).

[ Back ]

stent: An allotted portion; a stint.

This would suggest that Peg is taking with her whatever sewing

she has been assigned recently.

[ Back ]

the Academy: That Peg went to

school at the Academy, suggests that Jewett is thinking of this

story as taking place near her home in South Berwick, home of

the famous Berwick Academy. See "The Old Town of Berwick" for

further information about the Academy.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, assisted by Chris Butler, Coe College.