Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

THE STAGE TAVERN

It was early spring weather in a Maine town, so near the coast that cold sea-winds came sweeping over the hills. Some of the old winter snow-drifts, hard and icy and stained with dust from the bare fields, barred the road in places, and now and then a scurry of snow came flying through the air in tiny round flakes that hardly gathered fast enough to mark the wheel-ruts. Two persons, a man and woman, were driving together over the rough road in an open wagon. They were tucked up in a good fur robe, but it was a hard day, and a bitter wind to face.

The woman evidently belonged to that part of the country; she wore a homely old woollen shawl, and a small felt hat, which was so closely tied down by a thick veil that one could hardly tell whether she might be young or old, whether her shoulders were rounded and bent with hard work, or a slight young figure had only muffled itself against the harsh weather. The horse was unmistakably young, and the woman was unmistakably a good and sympathetic driver, not fretting him, even when she held him back and tried to check a forgivable desire to gain the journey's end.

As for the passenger, whose smart-looking, much-labelled, large portmanteau shifted from side to side in the back of the wagon as it went over the pitches of the snow-drifts, he was fine-looking, smooth-shaven and very stern as to his countenance, in the chilly March air. He was soldierly and businesslike, from the top of his stiff felt hat to the thick double sole of a city-made shoe, which now and then appeared in haste over the wagon-side, to keep balance as they tipped and jolted and jerked along the road.

At last, on a stretch of level, sandy ground, blown bare of snow and frozen into some degree of smoothness, the horse was allowed to choose his own gait; the wagon ran decently well in the ruts, and an unexpectedly young and cheerful voice made itself heard.

"We're more than half-way now; it's only two miles farther," said the driver.

"I'm glad of that!" answered the stranger, in a more sympathetic mood. He meant to say more, but the east wind blew clear down a man's throat if he tried to speak. The girl's voice was something quite charming, however, and presently he spoke again.

"You don't feel the cold so much at twenty below zero out in the Western country. There's none of this damp chill," he said, and then it seemed as if he had blamed the uncomplaining young driver. She had not even said that it was a disagreeable day, and he began to be conscious of a warm hopefulness of spirit, and sense of pleasant adventure under all the woollen shawls.

"You'll have a cold drive going back," he said, anxiously, and put up his hand for the twentieth time to see if his coat collar were as close to the back of his neck as possible. He had wished a dozen times for the warm old hunting rig in which he had many a day confronted the worst of weather in the Northwest.

"I shall not have to go back!" exclaimed the girl, with eager pleasantness. "I'm on my way home now. I drove over early to meet you at the train. We had word that some one was coming to the house."

"Can't they send people over from the station? Have you faced this weather once before to-day?" The traveller turned again to glance at the small head which carried itself with so spirited an air.

"Oh, yes!" said the girl, as if it were a matter of course. "There's hardly a week that I don't drive to Burnside four or five times, at least, since the shoe-shops were built. My brother is in school now. He takes my place on Saturdays and in the vacations, but I like to get out into the fresh air. The colt needs using, too. You can see for yourself!"

"I remember that there were some very fine horses here years ago," said the passenger. "I came here then to stay with a college friend, young Harris -- his father was old Squire Harris, a great politician, who kept the famous Stage Tavern. We both enlisted in our junior year, and were both badly wounded, but I got a commission in the regular army the last year of the war, and stayed there. I'm going now to see Harris. I'd like to surprise him. He's still at the tavern, I hear. I can't see why. He was meant for a very brilliant man."

"Yes, he's still there," answered the girl with pathetic reticence. "The wound in his head troubled his sight after a time," she explained, presently. "Major Harris is my father." The next moment she turned with sudden eagerness. "Oh, you must be General Norton, his friend, Jack Norton!" she cried. "He was talking about you only last night. 'I'd give anything if I could see Jack!' he said."

"We old army men on the Plains haven't had much chance for holidays," said the officer. "It used to take so long to come in that we ended by staying at the post. That's all done with in these days, though." He liked more than he could say to hear his old friend's daughter speak of him as Jack.

"Two of you are there, you and your brother?" he asked.

"Two of us, and my father," said the girl.

"And the old tavern?"

Then she laughed in a pretty, girlish way. "I should have put the tavern first," she said.

At this moment the sorrel colt took to his young heels with new excitement, and it was all a resolute hand could do to keep him steady along the village street. They rattled past a few pale, wooden houses that looked as if they had all been winter-killed, and whirled round a corner into the old tavern yard. A lame old hostler came out to take the colt by the head, and stood hissing gently at him, as if he were rubbing him down. The young girl got out of the wagon quickly, and stood waiting for her guest to follow. "I give you welcome in father's place," she said. "I must hurry to find him," and she led the way into the old house.

The soldier, left to himself, had an instant sense of warmth and shelter, and even of good cheer. He remembered well the large room into which they entered, and walked toward the great Franklin stove with a pleasant feeling of having got home. There was a fine fire blazing not a fire just kindled, and cold with new wood, but a good bed of live coals and half-burnt rock-maple logs. He pulled one of the comfortable old wooden armchairs before it and sat down.

There were some old maps on the walls of the room, and a fine engraving of General Washington over the high mantelpiece, which he remembered to have seen in his boyish visit. The same leisurely old clock ticked in the corner; behind the office desk were some shelves half-filled with businesslike reference books; on the disused bar itself were some piles of newspapers and magazines. There was a deep, old-fashioned painted tray of bright russet apples on a side-table, and a dish of cracked nuts, and an enticing jar, close-covered and striped blue and white, which was proved to contain crackers.

The general's healthy appetite was only controlled by a severe prudence; supper was sure to be at six, and the old clock had just passed half past five. He went resolutely back to the chair before the fire; there had come a preliminary waft of supper through the door by which his comrade of the drive had disappeared.

At that moment the door opened again, and he sprang to his feet. Without shawls and veils, Lizzie Harris proved to be one of the prettiest girls a man had ever seen. She had come out of her stupid-looking chrysalis, and stood before him like a bright young butterfly. The color was fresh in her cheeks; Jack Norton felt as if he had been driven over from Burnside depot by an angel in disguise.

"Father is coming," she said, and the unmistakable sound of crutches was heard along the wide hall that led through the house.

"Who's here, Lizzie?" said a man's voice, heartily. "You said somebody was asking to see me."

A most touching figure stood in the doorway; the tall, fine-looking man leaning heavily on his crutches, pale and worn with illness, was, saddest of all, unmistakably blind. Norton could not manage his voice to speak; they had last seen each other at twenty, young soldiers in Virginia, in '62, with life and victory bright before them. He went nearer and took hold of Tom Harris's hand.

"What! Who's this?" said the blind man. "Stop, don't tell me, Lizzie! Now say 'Tom Harris' to me once, and I'll make sure. O you dear old fellow! Why, Norton! Why Jack!"

"Well, my dear," said the general, a few minutes later, speaking affectionately, as if to make up for any dull surliness of the afternoon, "you see why I was in such a hurry to get here. Your father and I have got to make a night of it and talk about old times. I've never been much given to writing, nor he, neither, but you'll find we've got everything to say." The tears stood deep in his eyes, or he could have seen the tears in hers.

"You'll take us as you find us, Jack," said the tavern-keeper. "You won't have forgotten the old place?"

"Yes, it's too late now to make any change," said the girl, cheerfully. "Father has his supper in the dining-room. He likes to hear the talk and to sit here for a while afterward, and then we always read aloud a while until he is ready to go to bed. Here's my brother John, General Norton; he will take you to your room. Supper will be ready soon."

The blind man went to the foot of the stairs and gave a series of anxious directions for his old friend's comfort, but they were all unnecessary. There was a fire kindled in the fireplace, and the old portmanteau was unstrapped, and everything put in order in the best bedroom. There was a pleasant hospitality and cheerfulness about the old place most unusual in a country tavern.

As the boy ran down-stairs with impatient feet, the guest heard a lighter footstep, and looked up to see Lizzie Harris standing outside the open door. There was an eager wistfulness about her face, and he joined her at once.

"General Norton," she whispered, "I only wished to ask you not to discourage father about my being able to go on with the tavern business. He feels badly about it, and thinks my college work is all thrown away. I had the best chance for study that a girl can have, and two years ago, just as I finished at Radcliffe, my mother died. Father has had losses enough, and I see a very good chance ahead just now. Besides, it is home. It is a lovely country about Westford, and if I keep a first-rate house, people will surely find it out. If college is good for anything, it ought to help a girl to keep a tavern, and not hinder her!"

They both laughed. They understood each other like old friends, and Norton, being a man to whom deeds were easier than words, put out his hand to her, as if in sign of loyalty.

"Thank you for being so kind," she said, simply. "Now I'm going to hurry up your supper. Old Hr. Solomon Dunn is still here; he will expect you to remember him. He came to spend a few days when my grandfather was a young man, and never has gone away. He is the local genealogist and historian. He'll set you right about your own battles."

"Poor little girl!" said the general, half-aloud, as she hurried away. "I suppose everybody tries to make her feel that she is likely to lose the little money they have left. If gallantry will carry her through she's all right. She may make a bare living, but where's that boy's education coming from? What she wants are people who can pay good prices and appreciate her efforts. Perhaps I can do something for her in New York or out West. I'll see what sort of a supper it is," said the worldly-wise general, wagging his head.

The supper was excellent. Presently young Harris, eager with interest, came to the comfortable old-fashioned bedroom to mend the fire and make fresh offers of service. He showed such alacrity and intelligence that the guest found him quite fit to be his sister's brother. The general found his own war-worn heart quite touched by the way he was taken to the family heart. He had knocked about a more or less homeless world all his life, and there came flying into his mind as if he had that moment invented them, Shenstone's famous lines:

Whoe'er has travell'd life's dull round,

Where'er his stages may have been,

May sigh to think he still has found

The warmest welcome at an inn.

When he opened the door of the old office, he found a cheerful evening company had already assembled. Mr. Solomon Dunn was as impressive and oratorical as the low spirits of the last few minutes before supper would permit, and presented the distinguished guest by name to the occupants of the common room. Poor Tom Harris reached out his hand, and waited until his old friend came and sat beside him; then in a few minutes young John came and bade them all to supper. The supper was unexpectedly good; the whole place was so cheerful, so hearty in its old-fashioned comfort, that even some unusual refinements about the table restrained nobody, but only served to set a mark for behavior. Young Harris himself waited cleverly in his clean white jacket, and did it with pride and dignity. There was an honest-faced country girl who helped him; as for Lizzie, she was busy in the pantry, marshalling the prompt simplicity of the evening meal.

There were four or five speechless men who departed as soon as they had finished their suppers, and some others, more leisurely, who began to talk about public affairs, and were deep enough into their argument to carry their subject back to the office and finish it as they sat smoking about the fire.

The stranger found himself delightfully entertained. It was easy to forget poor Harris's blindness and infirmity when one heard him say the same sort of keen, amusing things as he used to in their old college days, and it was astonishing to find such good sense and knowledge of affairs in a company of men at least provincial, if not entirely rustic. Norton, who had been closer to some great political events than he was willing to confess, spoke frankly enough in his turn. The firelight flickered upon the wainscoting, and the portrait of Washington looked mildly down upon this group of American citizens.

"We don't begin to know yet what a great man he was," said Tom Harris once, at the end of an eloquent protest against short views in statesmanship.

As the old clock struck nine, one or two men got up and went away with friendly good nights, and the boy rose; his father took his shoulder instead of one of the crutches. "Come, Jack," he said, and they went across the hall into another room where the young hostess sat writing at a desk.

"Sit here, father," she said, and pushed the chairs toward another bright fire where a cat and dog lay in peace. The tavern office had been somehow most delightful, -- there was a kind of plain manliness and freedom about it, but this room was the place of a woman and home-maker. There were some old engravings, bought in the elder Harris's days of prosperity, and some good old furniture, but the contents of the plain bookcases of well-bound books had been added to and brought down to modern times, and there was a warm color and glitter of bindings on the shelves, the finest color that can be put into a room. And the soldier did not know what made the simple place so charming, only that a woman's fingers had set things right, and a woman's home-making instinct had made things comfortable.

"You and father must have your talk to-night," said Lizzie, picking up some things to take away with her. "We've just been reading the 'Autobiography of Lord Roberts,' and so he'll be all ready for more soldiering with you."

Both the men turned their heads wistfully toward her and bade her stay.

"I'll be back again," she said, gaily, and left them to the best evening's talk that two long-parted old friends ever kept going.

"I got hold of some mining interests in an idle way once, just before I got so damaged out among the Indians and had to retire. I find I'm getting so rich nowadays that I'm fairly ashamed! It doesn't feel natural," confessed the guest.

Tom Harris laughed; then he put his hand over his blind eyes as if they ached. "It wouldn't feel natural to me," he said, trying to laugh again. "I made a foolish step when this blindness was coming on me," he confessed. "I had these two children, and my wife was a delicate woman. I thought if I could add something to what I had that we could rub along, but I lost the better part of what my father left me, and then my wife died just as everything was getting dark I ought to have let things alone. We had let the old business here run down, but my dear little girl stepped right to the front. I can't bear to have her hidden away in this corner of the world. She stood at the head of her class."

The poor man's voice was beginning to falter. "You can see how it is with me, Jack. I have never been good for much as to health. Sometimes I think those fellows we went out with, who died in battle, had a far easier chance than those of us who have been giving our lives to our country, a little piece at a time, ever since."

The general sat close beside his old friend, where he could reach over and touch his hand. "She's had a chance to try her intellect, that girl of yours," he said, gently; "now she's trying her character. I wish she were mine. I'm getting to be a lonely old fellow," he said a moment afterward. "I haven't had such a happy evening as this for a long time."

"Stay with us a while," said the other, warmly. "You won't be running off to-morrow."

"No, no; if you can keep me a little longer," said the guest with eagerness.

There was a scar from a sabre-cut across General Norton's right cheek which gave him a look of age and experience in wars; but the left cheek was as smooth as a boy's, and his light brown hair was not in the least gray; you would have thought at the first glance at that side of his face, that he was a strong, soldierly man in the thirties. Somehow his character matched his looks. He had known such hardships and trying adventures, he had confronted so often what was worst and most treacherous in human nature, and had summoned so much oftener his stern authority, that he seemed to forget the power of gentleness, until something in itself gentle made him turn "the other cheek."

The bright fire was burning low, and even young John had grown sleepy and disappeared, when the mistress of the house returned, still bright and still caretaking. A thoughtful man like Norton found his heart touched by the sight of the girl's readiness. She had driven him across country that bleak day as if she liked it; she had known how to make him welcome; she was a queen among housekeepers; and now, when an hour of leisure came, she entertained him as he had seldom been entertained in his life.

They began to speak of that gallant soldier, Lord Roberts, and of the great page at the end of his story of the siege of Delhi. Perhaps the affectionate habit of bringing every amusing and interesting thing she could to enliven the enforced idleness and dull hours of her father's life, had developed Lizzie Harris's natural gifts, but she knew about politics and affairs as well as literature. She was what Norton called a woman with an education, and she knew how to put ambition into all her work.

It was an autumn day of that same year, and Lizzie Harris was again driving over from the Burnside station with General Norton for her only passenger. The sorrel colt was as light-footed as ever, but the country was full of beautiful color now; the valleys were still green, and on the hills the maples and birches had just begun to brighten like flowers thrown here and there among the dark green of the pines.

The hostess of the tavern looked a little older, and perhaps a little paler and more tired, but there was the cheerfulness of prosperity and all the brightness of success in her face. She had a comfortable balance for the first time in the old Westford bank.

She was telling the general about this in the frankest way, and how well her brother John had passed his final examinations and got into college, and that she hoped to keep him there. Somehow, although she talked so frankly, she did not look round at her companion as she spoke; there was something a little more formal in her manner than in the first visit. The general did not feel quite happy about this.

"You were so kind about sending me those delightful people! You cannot think how I enjoyed the weeks they stayed here," said Lizzie. "And father has been so happy over your letters! He wished so much to write you himself, poor father!"

"It was very good of you to write for him," said the army man, with strange brevity. "I suppose that I ought to congratulate you on all your success."

"Of course you ought," she answered; and then she turned and gave him one of the quick, unconscious looks which he had been missing. Each of these lovers wondered why the other had blushed, and each was deeply ashamed of blushing. The general was as shamefaced as a schoolboy, but he thought his companion had never looked so charming. He wondered if she would be glad to know how astonishingly well the Arizona mines were doing.

They let the sorrel colt take his own way up the long stretch of Pine Hill. Lizzie played with the whip in an absent-minded way, and the general began to talk about the weather.

"I thought that I was going to freeze to death that day I came, last spring," he said. "You did not seem to mind it at all. But I never have been so contented anywhere as I was here. It was like having a home of my own from the minute I stepped inside the door." Lizzie turned and looked off over the great valley.

"That's what I believe a tavern-keeper ought to try for. It is the only home the guests have while they are there," she said, proudly. "But we were so glad to have one of father's old friends come," she added, shyly, and then, mustering more courage, "I didn't know until you came how I -- how we had missed having somebody to talk with about larger things."

"Oh, I can't leave you again, now that I have found you," said the lover, who had not meant to speak so soon, or even, as he tried to make himself believe, to speak at all. "I'm a great deal too old for you, but your young shoulders oughtn't to carry everything. I want to help you look after the boy--and your father and I are old comrades. Couldn't you let somebody else have the tavern, and just make a home for -- for me?" asked the general, humbly. "I wish that I weren't such an old fellow!"

"You don't seem a bit old to me," said Lizzie.

The sorrel colt had just come to the

top of the hill; he tossed his head gaily and trotted on toward

the old Stage Tavern, and there were two happy hearts in the

carriage behind.

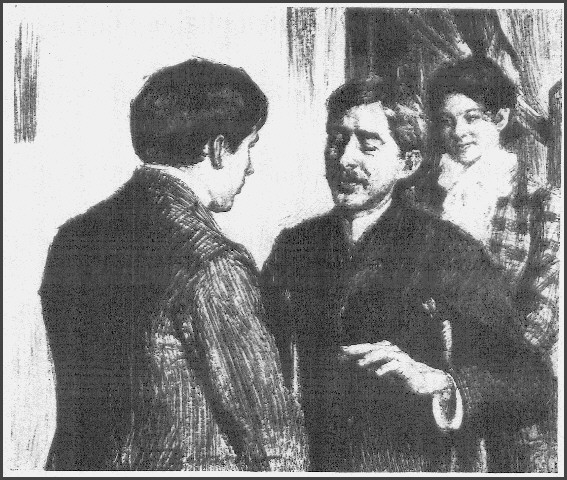

Illustrations for "The Stage Tavern"

These illustrations are by Margaret Eckerson, born 1883 in New

York. She was living at Mt. Vernon, NY in 1913. She studied with

Robert Henri. (Sources: Dictionary of Woman Artists by

Chris Petteys. Boston: Hall, 1985, and Mantle Fielding's

Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.)

Opening decoration

"Now say 'Tom Harris' to me once, and I'll make sure."

"The sorrel colt was as light-footed as ever."

NOTES

"The Stage Tavern"

appeared in Youth's Companion (74:184-5), April 12,

1900, where it was illustrated by an unidentified

artist. Richard Cary included the story in Uncollected

Stories of Sarah Orne Jewett. This text is from Youth's

Companion.

[ Back ]

the war: The

American Civil War of 1861-1865. It is possible that Jewett

took General Norton's name from the name of an owner of a

local South Berwick tavern. The Old Berwick Historical

Society reports that Winthrop B. Norton built a tavern on what

is now Main Street, not far from Jewett's home. A widow,

Sarah Frost, purchased it in 1816, and it became the Frost

Tavern until 1848. The Frost Tavern is preserved in

local memory as a main scene in a visit by the Marquis de

Lafayette, mentioned several times in Jewett's works, e.g.,

"Peg's Little Chair." In Jewett's day, the establishment

was called Paul's Hotel. This was familiar local history

during Jewett's lifetime. For more information:

http://www.obhs.net/2am.html

[Back ]

Franklin stove:

type of wood-burning stove, invented by Benjamin Franklin (c.

1740). The Franklin stove burned wood on a grate and had

sliding doors that could be used to control the draft (flow of

air) through it. Because the stove was relatively small, it

could be installed in a large fireplace or used free-standing

in the middle of a room by connecting it to a flue. Its design

influenced the potbellied stove. (Source: Britannica

Online; research, Barbara Martens).

[Back ]

rock-maple logs: Also

known as the sugar maple or hard maple. A large tree in the

maple family native to eastern North America and widely grown

as an ornamental and shade tree. (Source: Britannica

Online; research, Barbara Martens),

[Back ]

General Washington:

(1732-1799), commander of the American Revolutionary Army and

first president of the United States (1789-1797).

[Back ]

Radcliffe: A

number of Jewett's friends were involved with the founding and

operation of The Harvard Annex and then Radcliffe College, by

which women became associated with Harvard College in

Cambridge, Massachusetts. Helpful information also appears in

Sally Schwager's Harvard thesis, "Harvard Women": A

History of the Founding of Radcliffe College (1982).

[Back ]

Westford: This

appears to be a fictional town.

[Back ]

Shenstone's famous lines: William Shenstone (1714-1763) was and English poet, amateur landscape gardener, and collector. With Bishop Percy he edited Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). The lines are from "Written at an Inn at Henley":

To thee, fair Freedom, I retire

From flattery, cards, and dice, and

din;

Nor art thou found in mansions higher

Than the low cot or humble inn.

'Tis here with boundless power I reign,

And every health which I begin

Converts dull port to bright champagne!

Such freedom crowns it at an inn,

I fly from pomp, I fly from plate,

I fly from Falsehood's specious grin;

Freedom I love, and form I hate,

And choose my lodgings at an inn.

Here, waiter! take my sordid ore,

Which lackeys else might hope to win;

It buys what courts have not in store,

It buys me freedom at an inn.

Whoe'er has travell'd life's dull round,

Where'er his stages may have been,

May sigh to think he still has found

The warmest welcome at an inn.

(Research: Chris

Butler).

[Back ]

Autobiography of Lord Roberts:

Frederick Sleigh Roberts was born September 30, 1832 in

Cawnpore, India and died November 14, 1914 in France. He was

the last man to serve as the British Army's commander in chief

(the office was abolished afterward), and did so for both the

Second Afghan War and the South African War. His autobiography

was entitled Forty-One Years in India: From Subaltern to

Commander-in-Chief and was published in 1898 by Longman,

Green, and Company in New York. (Research: Chris Butler).

[Back ]

the other cheek:

See Matthew 5:39.

[Back ]

siege of Delhi:

The great revolt of India was started in 1857 when mutinying

troops of the Bengal army took Delhi. After this successful

capture, mutiny turned into full-scale revolt. The British

engaged in a dramatic and ultimately successful siege of

Delhi; this was one of the main elements of the British

counter-attack. (Research: Chris Butler).

[Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, assisted by Chris Butler, Coe College.