Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

Introduction to "Tame Indians" by Sarah Orne Jewett

In addition to these notes, there are supporting documents of two kinds:

SARAH O. JEWETT.

I was visiting a friend of mine in Boston not long ago, and one Sunday afternoon her younger brother and sister asked me to tell them a story; but I could not think of any, and proposed reading them one, instead.

"Oh! no," said Bessie; "tell us about something that you did once. Didn't the cars ever run off the track when you were traveling? Or tell us about something you have seen. I like that kind of story best."

"So do I," said Jack. "I like to hear Indian stories, too."

"Why," said I, "I can tell you about some tame Indians I saw once. I went to an Indian church out West." So we all went to the bay window to sit together on a cozy little sofa, and I began.

"It was in Wisconsin, about three hundred miles north of Chicago. I had been there a day or two and had said once or twice how funny it seemed to me to see the Indians walking about the streets. The only ones I had ever seen before were the forlorn creatures who live at watering-places in the summer and make fancy baskets to sell to the summer visitors."

"Yes," said Jack, "we used to go to see some at North Conway last summer. Don't you remember, Bessie?"

"When you are older, Jack," said I, "if you are still fond of war stories, you must read Mr. Parkman's books. There is one called 'The History of the Jesuits in North America,' where you find a great deal about the old Indian tribes. I'm afraid you will not admire them quite so much as you do now -- they were so horribly cruel. Though I suppose in these days we only know the worst side of the story."

"Does that book tell about fights and splendid Indians who knew all about hunting? I think I should like to read it now," said Jack: while Bessie said: "Please go on."

"There were two young ladies besides myself, and we started as early as eight o'clock; for it was a hard, long drive, at any rate, and some one told us the road was unusually bad just then. It was a sudden start -- just at dusk the night before[,] I had rushed to the window to see a passer-by, and came back to where my friend was standing, saying 'He wasn't an Indian, after all,' when she said:

"'What a pity you couldn't go out to 'the Mission' to church. You would see them there to your heart's content. But, for the life of me, I can't get up any enthusiasm. I think they are stupid, lazy creatures.'

"She said this because I was so excited about them and had been asking her to look at every one I saw. Next morning was Sunday, and I was waked very early and hurried all the time I was eating my breakfast, because we were really going to Oneida, and I was so glad. I can't tell you much about the drive, only that it was dreary and tiresome. There were no hills, but there were rough places enough in the road. It was November and the sky was gray. The day before had been rainy, and we had a dozen miles to drive, most of it through the forest, or what had been a forest before those awful prairie fires of 1871 had swept through it. We were not many miles from Peshtigo. You remember hearing of the terrible fires there, don't you, at the time Chicago was burnt -- when whole villages were destroyed and ever so many lives lost? I think those woods were more dismal than any place I ever had been in before. The green ferns and underbrush, which must have made it pleasanter in summer, had all been killed by the frost. There were half-frozen pools of water in the low places, and the charred and blackened trunks of the pine trees were standing everywhere as far as you could see, and black cinders and broken branches that had fallen were scattered over the ground. It seemed as if we never should come to the end of that forlorn road and find houses and fields again. But by and by we heard a church-bell ringing; and then the sun came out, and presently we saw the farms and the church itself, and there was the Mission at last, and we left the woods behind us. The driver whipped up his horses, and on we went in a hurry; but we still had some distance to go, and were late, after all."

"What did the wigwams look like?" said Jack.

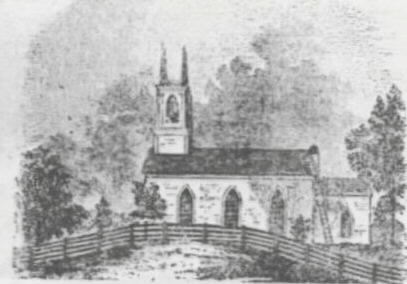

"There were no wigwams at all," said I; "only log cabins and small frame-houses. It looked almost like any other little Western settlement. I was so disappointed, for it did not look at all as if Indians lived there. The church was like any little country church."

"Oh! what a pity," said both the children.

"But when we left the horses and went in -- oh! I wish you could have seen the congregation! If the houses had looked like ordinary houses, their owners certainly did not look like ordinary people. Their faces were just like the pictures of Indians in my old story-books, and I think I shouldn't have been much surprised if I had been scalped or tomahawked on the spot. They looked stupid and peaceable and seemed very devout; and the church was filled, all except the strangers' pew."

"What kind of a church was it?" asked Bessie.

"Episcopal," said I, "and it was so strange that the Sunday before I should have been at Grace church, in New York, where everything is so beautiful and the people such a contrast to these; and then one week afterward here I was, a thousand miles away, at the Oneida Mission -- myself, my friends, and the clergyman the only white people to be seen in the congregation. I was so sorry that I was just too late to hear them say the Creed; but I heard the responses afterward, and they sang two hymns in their own language. One was 'Am I a Soldier of the Cross?' They do not have all the usual Church service; but a much shorter and simpler one, leaving out parts they could not understand. We had Prayer Books with the Indian on one side and the English on the other, and a few hymns translated at the end. They seemed to know the hymns by heart, and their singing was very good and interested me more than anything. The tunes sounded so familiar and the words so strange."

"Do you remember any of the words?" asked Jack.

"Not one. I'm so sorry!["] The service was all in Indian, but the sermon was in English and there was an Indian interpreter. At the side of the pulpit, just inside the chancel-rail, was a place like a small, old-fashioned square pew; and here stood a solemn old Indian, who listened to the English sentence and then repeated it in his own language. He had a fine, deep voice and a grave manner, and used many gestures, so he reminded me of what I had read of the speeches the braves made around the council-fires.

"Was it like the sermons we have Sundays here?" asked Bessie.

"Yes, only shorter and much more simple -- just such a sermon as would be preached to children. I remember I liked it exceedingly."

"How were they dressed? I suppose they wouldn't have feathers in their hair for church, anyway," said Jack.

"Oh! no," said I. "The men wore rough, plainclothes, like other men; but the squaws were very droll. They had no bonnets, though I used to see them in the town, sometimes, with big felt hats. There at church they all wore bright-colored handkerchiefs, folded once cornerwise and tied over their heads and under their chins. They wore gay-colored calico and woolen dresses, and some of their shawls, which they used now instead of the old-time blankets, were fairly dazzling. They all looked lazy and good-humored -- except a few of the older ones, whose eyes were like hawks -- and as if they never heard of going on the war-path, or of burning people's houses and murdering them in their beds, or of carrying them off captive through the woods in winter. They were not your favorite kind of Indians, Jack. I'm afraid they would disappoint you. I think the Oneidas were always a peaceable tribe. This company that I saw at Duck Creek, as they call the settlement, are all that are left of the great tribe, and it was pitiful to think how they have been pushed further and further back from the sea and are being crowded out of the world."

"But I'm ever so glad," said Bessie, energetically. "It makes me afraid even to read about Indians, and I think these are the nicest ones I ever heard of. I am glad there isn't room enough in the world for them. Wicked things!"

And I thought if we only would crowd the wicked thoughts from our hearts by putting better ones in it would be a capital plan, and then it flashed into my head that the Indians had been like weeds in the garden, which have to make room for the flowers always; but that the white people, some of them, have no right to the Indians' places, for they are no better than they were. And I was just going to say something about this to the children, when I happened to think how funny the Indian babies were.

"After service was over," said I, "we watched the people go away, and laughed to see all the pappooses ride off in state on their mothers' backs, rolled up so cozily in the shawls."

"Oh! do tell us some more about the pappooses!" said Bessie, eagerly. "Had they been in church all the time?"

"Why, certainly, and they behaved well; only sometimes one would talk a little, and that would put it into the minds of the rest, who would follow, like chickens. Once in a while one cried a little; but they were evidently used to being in church. There was such a serious baby in the next pew to me, who stared hard at me nearly all the time with his little, round, black eyes.

"After they had all gone away, we had a pleasant little talk with the missionary, who told us he had lived there twenty years, and that the people were going to build a new stone church soon. And he showed us bead-work and pretty moccasins that the squaws had worked, and told us how much they are like children, and that they rarely save money; so when they are ill and old they are very forlorn. They are superstitious and remember many of the strange old legends; and I should like so much to have talked a great while longer, and to have asked him to tell me the legends and more about his parish. He had a sweet, kind face and seemed so fond of them and so proud of their progress since he came to live with them. The mission-house was very pleasant and he did not seem lonely.

"Then we came away, and, as we had brought our lunch in a basket, we had a merry time eating it, and the sun was bright, and we were quite jolly going home. We passed several Oneida families, and they never walked side by side, but in true 'Indian file,' children and all, and the pappooses peeping out from the shawls. It was such a wonder to me that they didn't slip down to the ground."

"Suppose we try with Tatters? There's Mamma's carriage-shawl in the hall," said Jack, who is fond of experiments. But the little dog was nowhere to be found, and his master came back to ask if there was any more of the story.

"No, there is not," said my friend,

his elder sister, who had come down-stairs. "But we are going

for a walk and to see the sunset, and you and Bessie may come

too, if you like."

Notes & Illustrations

| "Tame

Indians" appeared in The Independent (27:26) on

April 1, 1875. Probable errors are corrected and

indicated with brackets. [back] Chicago: Jewett made

this visit to Green Bay, Wisconsin, (actually about

200 miles north of Chicago) in November of 1872.

Little is currently known about this trip, but it

seems likely that she was visiting the family of Henry

Jewett Furber, Sr. I went on to New York the 24th of October. Stayed there until early in November. Then went to Cleveland with the Furbers & then to Chicago. Then up to Green Bay, Wisconsin. Where I had three very happy weeks and where I think I was better and kinder & more useful than during any three weeks I can remember. It makes me conscious of my capabilities for usefulness and goodness more than any other visit ever did!In another entry for 14 August 1874, she writes: "This has been a very pleasant summer: I went to New York and then out to Wisconsin & then back to New York with the Furbers…." Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett to Anna Dawes show Jewett staying for about two weeks with Mrs. Henry J. Furber at the Windsor Hotel in New York City in mid-June of 1876 ["Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett to Anna Laurens Dawes," by C. Carroll Hollis. Colby Library Quarterly 8:3 (September 1968), 107-109]. From Houghton MS Am 1743.1 (341), published by permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University. Distantly related to Sarah Orne Jewett, Henry Jewett Furber's family lived at Somersworth, NH, just a few miles from South Berwick, during his childhood. Henry J. Furber, Sr., resided in New York City rather than in Green Bay during the 1870s, but his three young sons lived with their maternal grandmother, Mrs. Alexander Irwin, in Green Bay and attended school there. It is likely, though not yet established, that Jewett and perhaps other members of the Furber family, perhaps even Elvira Irwin Furber, Henry Senior's wife, traveled together to Green Bay to visit these children. In the opening pages of her 1871 diary (Houghton Library), Jewett lists among her friends and correspondents, Emily Irwin, Elvira's sister, and Mrs. Furber. Click here for details about the Henry Furber family. [back] watering-places…North

Conway: Presumably Jewett refers to resorts,

mineral springs or seaside towns, where one goes to

drink mineral waters or bathe in mineral or salt

water. However the context suggests a more general use

of the term to refer to any popular vacation resort,

such as North Conway, in east central New Hampshire.

Jewett's narrator apparently has so far seen Native

Americans only in such resorts, where they were viewed

mainly as beggars. It would be a novelty to see them

going about ordinary business in Green Bay. Parkman's books. There is

one called 'The History of the Jesuits in North

America': Francis Parkman (1823-1893) published

The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth

Century in 1867. He wrote several other books

that dealt extensively with Native Americans, such as

The Oregon Trail (1849) and The History of

the Conspiracy of Pontiac (1851). worst side of the story:

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills of North

Dakota in 1874 drew numerous white prospectors into

Sioux territory, producing many violent clashes and

leading to the Battle of Little Big Horn in June 1876.

News accounts of the time emphasized the "savagery" of

Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and their fighters. just at dusk the night

before: In the Independent text, it

appears there is a period after "before", but the

grammar seems to make more sense if a comma is placed

there. stupid, lazy creatures: The narrator's friend seems fairly hostile to the Oneida. There is some historical basis for this. During the 1860s and into the early 1870s, the local "Indian Agent" for the United States, apparently encouraged by local businessmen, and conniving with discontented factions among the Oneida, made a number of efforts to force the Oneida off their reservation. In her 1868 diary, Ellen Goodnough reflected upon one of these attempts, when the agent tried to persuade the Oneida that the government had forbidden them to cut timber on their reservation: "Thursday -- The agent has been on the Reservation, forbidding the cutting or selling of any sort of timber. This will cause terrible suffering among our people. They depend upon the sale of the timber just now to clothe themselves, and in a great measure for food, as the corn and potato crops failed entirely last season. The potatoes were destroyed by the bugs, and the corn by the rain. For 40 years the Indians have carefully cut all the timber they wanted, and now they are forbidden to cut their own timber, on their own land, and paid for by money of their own. For they sold their land in New York and with the money bought this tract of land.

"I must tell you of a new and delightful experience I had last Sunday. I went out to the Oneida settlement which is about twelve miles from here. There is an Episcopal church and the congregation are all Indians. I never had seen many before and these looked so like the Indians in my picture books when I was a little girl, that I half expected to hear the war-whoops and to be scalped and tomahawked before I knew it. They were very devout and are said to be a most pious community but they certainly do not look so. The rector told me he had lived there twenty years. I had a very nice talk with him. The Sunday before I was at Grace Church in New York, and I was very much struck with the contrast in the two congregations!" (See the first letter in the Parsons selection).In Jewett's diary entry of 23 May, 1873, noted above, she reports her sorrow at not taking her diary with her during her travels in the autumn of 1872. She gives an itinerary that places her in New York City on Sunday 24 October, and then in Cleveland, Ohio in early November, before going on to Chicago. If she attended Grace Church in New York on Sunday 1 November, she would have been able to attend service at the Hobart Church on November 8, the first Sunday after arriving in Green Bay, so she could report about it to Parsons on the following Saturday, November 14. In her diary, she says she spent three "happy weeks" in Green Bay. After the stay in Wisconsin, she visited in Chicago again, Cincinnati, Ohio, and in Chicago for another two weeks, before spending the Christmas holidays in Brooklyn, New York. This would seem to place her stay in Green Bay as beginning at least a few days before 8 November and extending 3 weeks, until nearly the end of the month. Jewett was able to visit all of these comparatively distant places in such a short time because of the railroad. For example, the Northwestern Railroad route from Chicago to Green Bay opened in 1862. [back] those awful prairie fires of 1871: Violent fires swept through extensive areas of Michigan and Wisconsin all around Lake Michigan on October 8-14, 1871, killing more than 2000 people, according to the Dictionary of American History. More than 1100 people died near Peshtigo (pésh-tee-go), a town north of Green Bay, the hardest hit area in terms of casualties. A mural triptych at the Peshtigo Fire Museum shows the residents of the village seeking shelter by submerging in the cold waters of the Peshtigo River, where many who were not burned died of hypothermia. The tragedy was widely reported in national newspapers. For further information, see: Susan Fenimore Cooper (see the

missionary below) describes how the fires

affected the Oneida mission: "In the month of October,

1871, occurred the terrible forest fires which

destroyed many small hamlets in Wisconsin, and in

which not a few lives were lost. These fires were

raging with great fury at no great distance from the

Oneida Reservation. Small settlements and farms were

destroyed, and broad reaches of forest entirely

burned. The air was thick and oppressive with smoke. A

constant watch was kept up on the Reservation day and

night. The flames reached the Oneida forests and

destroyed much timber. But no buildings of any

importance were injured. The fences at the mission

were burned, and the Church parsonage and school-house

in much danger. They were only saved by vigilant

watchfulness, day and night." the time Chicago was burnt:

The Chicago fire also occurred October 8-10, 1871.

Some speculate that these many fires -- over a large

area starting on the same day -- could have been

caused by a meteor shower, such as the Leonids, which

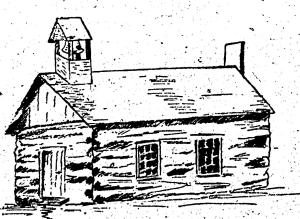

occurs annually at about this time. bell ringing: The church

bell of Holy Apostles Church at Oneida is one of the

remaining artifacts of the 1839 Hobart Church. Holy

Apostles burned in 1920, and the damaged bell had to

be recast. no wigwams at all: The

Webster 1913 dictionary defines a wigwam as "An Indian

cabin or hut, usually of a conical form, and made of a

framework of poles covered with hides, bark, or mats;

-- called also tepee." The Oneida, historically, were

an agricultural tribe, living in settled communities.

Their traditional houses were not exactly wigwams, but

"long houses," constructed of wood and bark. When

Jewett visited the Duck Creek settlement, most of the

homes were, as she reports, of logs or framed lumber.

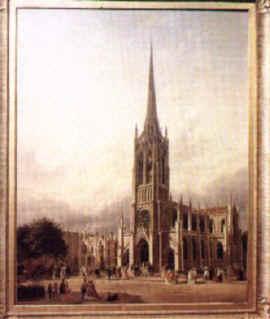

See photos to right. Grace church, in New York:

Grace Episcopal Church in New York City stands at 802

Broadway (at 10th Street). Established in 1809, Grace

Church eventually became a fashionable church,

attended by New York elite. The present Gothic

building, designed by James Renwick, Jr., was erected

in 1846, with additions of stained glass and memorials

in the years since. the Creed; but I heard the responses afterward, and they sang two hymns in their own language. One was 'Am I a Soldier of the Cross?': The Apostle's Creed -- with some variations -- is the statement of faith in most denominations of Christianity. "Am I a Soldier of the Cross?" (Sources give two composition dates: 1709 and 1724) is by Isaac Watts (1674-1748). Text and music appear at this URL: http://tch.simplenet.com/htm/a/amiasold.htm. The hymn begins:

Am

I a solder of the Cross, (Research assistance: Rich

Adkins) Prayer Books with the Indian on one side and the English on the other, and a few hymns translated: The Oneida prayer book was originally in Mohawk, which varies only slightly from Oneida, and so was readily understandable to the congregation. The first translation was made by Rev. Eleazer Williams, the first missionary to the Wisconsin settlement, early in the nineteenth century. Susan Cooper points out, however, that the prayer book was improved during Rev. Goodnough's tenure: The library of Oneida books, if not large, was of very great value to the people. There was a translation of the New Testament, complete with the exception of Second Corinthians; portions of the Old Testament; the prophesy of Isaiah; a hymn book compiled chiefly from our own; and three different editions of the Prayer Book. The Rev. John Henry Hobart, son of the revered Bishop Hobart, and one of the founders of Nashotah, who had been ordained priest in the little church at Oneida, had inherited the Bishop's interest in the people, and gave them an improved translation of the Prayer Book, published at his own expense. The translation was prepared by the skilful interpreter, Baptist Doctater. The people valued this last translation greatly, and often read it in their homes with pleasure.The narrator's interpretation that the prayer-book had been simplified for the unsophisticated Oneida probably is in error, there being no confirmation that services were simplified, though the book may not have contained all of the various services, such as for baptism. Furthermore, it seems clear that the long-term intention of the mission was that the Oneida would learn English and shift from the short Oneida book to the complete Book of Common Prayer in English. For example, the missionary, Rev. Goodnough, was especially proud of his success in encouraging the Oneida to become "more civilized," and one of the signs of his success was their increasing use of English. Susan Cooper also reports with approval the difficult but steady progress of the nineteenth-century Oneida in shifting to English as their main language. The Williams translation appears at this web site: http://justus.anglican.org/resources/pc/bcp/oneida1816.html [back] their singing was very

good: The Oneida have a reputation for the

cultivation and appreciation of music. In The

Oneida (1906), Julia K. Bloomfield says, "There

was an organ of good tone well played by the regular

organist, one of the chiefs. The singing was always

very sweet. Never indeed were the services carried on

without the sweet plaintive voices of the women being

heard in the chants and hymns in their own language.

Not a few men also had good voices. The people seem to

have a natural taste for music" (Chapter 19). an Indian interpreter:

The Goodnough obituary and Susan Cooper both note that

Rev. Goodnough gave his sermons in English and had

them translated into Oneida as he spoke. Both also

emphasize the simplicity of his messages, though

Cooper suggests that this simplicity was required at

least in part because of the difficulties of

translation, suggesting that the supposed "simplicity"

of the listeners was not the only reason. The records

of Holy Apostles show that B. Doxtator was paid to be

interpreter in 1872, the year of Jewett's visit.

Probably this was Baptist Doxtator, a member of the

parish, who was first paid to interpret in 1860.

Cooper points out that Baptist Doctater was a skilful

interpreter and translator, and that he provided an

improved translation of the Prayer Book. If this

identification is correct, he might well have appeared

relatively elderly to the 23-year-old Jewett in 1872;

he married in the church in1848, but appears to have

started his family in 1846, when the baptism of his

first child with his wife, Mary Bear, is recorded.

These dates would suggest that he was probably over 40

years old in 1872. "The functions of orator, among the Five Nations, had even become a separate profession, held in equal or higher honour than that of the warrior; and each clan appointed the most eloquent of their number to speak for them in the public council.… The orator does not express his proposals in words only, but gives to every sentence its appropriate action. If he threatens war, he wildly brandishes the tomahawk; if he solicits alliance, he twines his arms closely with those of the chief whom he addresses; and if he invites friendly intercourse, he assumes all the attitudes of one who is forming a road in the Indian manner, by cutting down the trees, clearing them away, and carefully removing the leaves and branches. To a French writer, who witnessed the delivery of a solemn embassy, it suggested the idea of a company of actors performing on a stage." ("The Intellectual Character of the Indians")[back] fairly dazzling: Susan

Cooper confirms that the men wore conventional

American dress, while the women wore traditional

Oneida clothing and decorations. Cooper also points

out that men and women sat on different sides of the

church. From Ellen Goodnough's diary of 1866: "The

congregation looks very different from what it did

when we first came here. Then, in the warmest weather,

the women were wrapped in white blankets, or else

squares of black or blue broadcloth, some of the

latter richly embroidered. Now we never see a blanket

in Church. They wear shawls of the brightest and

gayest colors pinned at the throat. A veil or

handkerchief, or occasionally now a hat, is worn on

the head. The young people sometimes wear gorgeously

trimmed hats. A lady visiting me, told me that walking

behind a young girl she counted seven different kinds

of ribbons on her hat" (Bloomfield, Chapter 20). peaceable tribe: The

narrator's speculation is correct, at least with

regard to recent history. The Oneida attempted to

remain neutral in the American Revolution, and then

joined the American side, with the understanding that

they would retain their ancestral lands. However,

Parkman points out that as one of the Iroquois Five

Nations, the Oneida participated in the Iroquois War

against the Hurons and the early seventeenth-century

Jesuit mission, and in The Old Régime in Canada

(Chapter 13, 1893 edition), Parkman says that the

Oneidas were among the more hostile and aggressive of

the Five Nations in opposing the renewed inroads of

French colonization in the 1660s. Through snow and ice and storm, Hertel and his band were moving on their prey. On the night of the twenty-seventh of March, they lay hidden in the forest that bordered the farms and clearings of Salmon Falls. Their scouts reconnoitred the place, and found a fortified house with two stockade forts, built as a refuge for the settlers in case of alarm. Towards daybreak, Hertel, dividing his followers into three parties, made a sudden and simultaneous attack. The settlers, unconscious of danger, were in their beds. No watch was kept even in the so-called forts; and, when the French and Indians burst in, there was no time for their few tenants to gather for defence. The surprise was complete; and, after a short struggle, the assailants were successful at every point. They next turned upon the scattered farms of the neighborhood, burned houses, barns, and cattle, and laid the entire settlement in ashes. About thirty persons of both sexes and all ages were tomahawked or shot; and fifty-four, chiefly women and children, were made prisoners. Two Indian scouts now brought word that a party of English was advancing to the scene of havoc from Piscataqua, or Portsmouth, not many miles distant. Hertel called his men together, and began his retreat. The pursuers, a hundred and forty in number, overtook him about sunset at Wooster River, where the swollen stream was crossed by a narrow bridge. Hertel and his followers made a stand on the farther bank, killed and wounded a number of the English as they attempted to cross, kept up a brisk fire on the rest, held them in check till night, and then continued their retreat. The prisoners, or some of them, were given to the Indians, who tortured one or more of the men, and killed and tormented children and infants with a cruelty not always equalled by their heathen countrymen.[back] crowded out of the world:

It is not quite true that the Wisconsin Oneida were

all the Oneida left in the world. After the American

Revolution the larger number of Oneida returned to the

Thames River area in Ontario, Canada. Wicked things:

Bessie's fear of Indians would not have been unusual

when this story appeared. Wars between Native

Americans and various representatives of the United

States were frequent in the 1860s and 1870s. See notes

and Jewett's letter to Parsons quoted above. Also

relevant would be Jewett's knowledge of South Berwick

local history; see her accounts of the raids by Hertel

on her home neighborhood and the captivity of Hetty

Goodwin in "The Old Town of Berwick" and in The

Tory Lover Chapter 32. like weeds in the garden: Here Jewett echoes

in image and idea what Brian Dippie identifies as a

major strain in American thought about Native

Americans. In The Vanishing American (UP of

Kansas, 1982), Dippie quotes Edward Everett, writing

in the 1820s, "It is not necessary to exterminate a

savage tribe -- place the germ of civilization in

their soil -- and such is the living principle … of

the arts of civilized life, that it will strike root,

shoot up, and spread" (30). Jewett's reading in

Parkman's The Jesuits in North America

elaborated and substantiated this kind of thinking. At

the end of his book, Parkman argues that the Iroquois

destruction of the Hurons and the Jesuit mission to

Canada contained the seeds of their own

self-destruction, and that this was part of a

Providential design to eliminate Indian barbarism and

Jesuit absolutism from American soil, to smooth the

way for Protestantism and democracy (Chapter 34).

Indeed, Parkman believed that Native Americans were

incapable of becoming civilized except by individual

assimilation and absorption into European culture. In

the first chapter of The Jesuits in North America,

he describes the Indian tribes as all of one race, and

that race "hopelessly unchanging in respect to

individual and social development…." Native Americans,

therefore, are doomed to vanish, to make way for

Protestant, American civilization. pappooses: The text

uses this spelling throughout the story; I have not

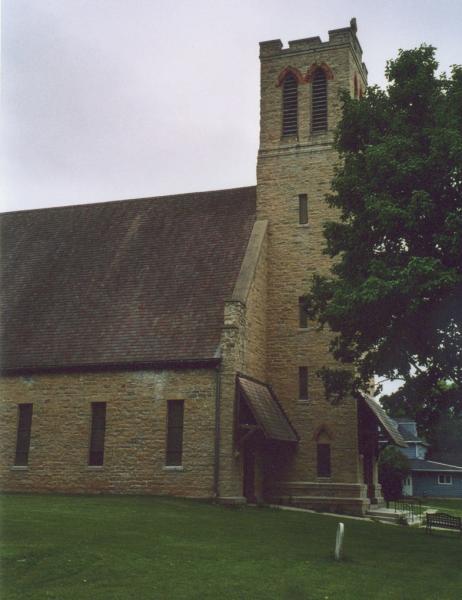

changed it to the modern spelling. the missionary: The missionary at Hobart Church in 1872 was Rev. Edward A. Goodnough. The story of his life and work at the Oneida reservation is told by Susan Fenimore Cooper in her account of "Missions to the Oneidas," originally published in The Living Church, 1885-1886. Her account appears at this web site: http://external.oneonta.edu/cooper/susan/missions.html. Cooper says that Rev. Goodnough (good-no) took charge of the mission church in 1853, and was soon joined by his young wife, Ellen Saxton Goodnough in 1854. They labored together at the mission and school until her death in May 1870. Goodnough remarried in about 1872, and he continued working at the mission until his death, serving about 36 years. Obituary / Biographical Sketch of Rev. Edward A. Goodnough <Selections from Susan F. Cooper's account of Goodnough's mission work. [ back ] new stone church soon:

Susan Cooper and the Goodnough obituary provide

details about the new church building, which was

completed in 1886. Notable in these accounts is the

quantity of labor over several decades that the Oneida

community put into quarrying and transporting the

stones from which the church was built and raising

funds for the building. The women made and sold craft

items as part of this effort. Not only did they make

beadwork, moccasins and quilts, but they learned the

art of lace-making from missionaries and made fine

lace items to sell, bringing in several hundred

dollars per year according to TA LUH VA WA GU

(10). This picture of industriousness on behalf of the

church -- along with other attainments hinted at in

Jewett's text -- would seem to qualify the

descriptions here of a people who appear lazy and

stupid. old legends: Ellen Goodnough, in her diary, records various instances of Oneida "superstition," which probably should be understood as the persistence of traditional beliefs that she and at least some Oneida saw as in conflict with their newer Christian beliefs. One of these is the death feast: "There is a death feast to-day. This is one of the old heathen customs they will keep up and cling to. They believe when a person dies the spirit stays in the house 10 days. On the tenth the relatives of the deceased make a feast in the house of mourning, and all partake of it in profound silence. Not a word is spoken excepting by the one appointed to speak of the departed and call to remembrance any little incident of the individual's life, dwelling on the good qualities. They say if this ceremony is omitted the departed one is sad and hungry" (Bloomfield, Chapter 20)Ellen Goodnough also records at least one "legend" in her diary: "One old woman makes medicine to guard against witches. Old John House was famous for this. One summer about ten years ago, a witch appeared in the form of a large black hog. It appeared only at night, running after people and making awful noises. One night it chased a party of young men, who turned upon it with stones and clubs, pounding it soundly, when to their great astonishment old John House cried for mercy. He was ill for some time after this pounding, and had hardly recovered when a new witch appeared in the form of a wildcat. It was always in some tree and made the most hideous noises imaginable.[back] he did not seem lonely:

The narrator's remark on Goodnough's solitary life

seems a little strange for several reasons. It appears

the narrator visited him on a day when none of his

family happened to be at home. He had at least five

children under 18 years old in 1872. Though his first

wife had died in 1870, the Goodnough obituary

indicates that he married Mrs. Frances A. Perry in

"about 1872," and that Mrs. Perry had been keeping the

mission house before the marriage. Day and Date: Thursday, July 27,1871 The narrator's report of

Goodnough's pride about the Oneida is reflected in his

obituary, where he is quoted: "The grand work of

Christianizing the Indians is still going on. They are

eager and willing to be taught the ways of the white

men, and exhibit a great advancement in methods of

civilization. During my stay here, I have encouraged

them especially to speak English, and to adopt our

manners and customs. The progress they have made is

owing to the church, more than to any other one

thing." didn't slip down to the

ground: Oneida mothers used traditional cradle

boards to carry their infants on their backs. The

cradle board would ordinarily include a foot board or

straps that would prevent the child from slipping

down. Jewett might easily have missed such details,

since they would be covered by the warm wrappings.

This detailed description appears in the 1866 diary of

Ellen Goodnough: "We do not often nowadays see babies

on their Indian cradle-board. When we first came here

we never saw them on anything else. They were then

baptized so. We used to see them hanging up in the log

houses, or perhaps suspended from the branch of a

tree, while the mother would be hoeing corn or digging

potatoes near by."

|

These images

Train arrives at Green Bay

Henry Jewett Furber

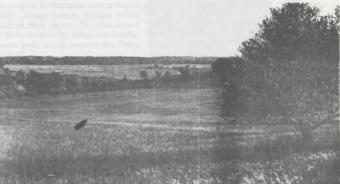

Panorama of the Old Ridge Road

Oneida log home

Oneida frame house

Drawing of the Hobart Church

Grace Episcopal Church

The first Hobart Church

Oneida Family, about 1894

Oneida home interior in 1906

Aliskwet (Elizabeth) Huff

Women grinding grain.

Members of the Hobart Guild

Oneida men working

Two Oneida babies

Rev. Edward A. Goodnough

This picture of Rev. Goodnough

The mission house

Rev. Cornelius Hill More photos of Hill from Bloomfield

Oneida bead work

Oneida basket work

Holy Apostles Church, Oneida

More photoes of Holy Apostles

Church

Sources of Images

The Oneidas, Julia Keen Bloomfield 1907 Sagole...A Greeting from the

Oneidas TA LUH VA WA GU -- a booklet published for the 150th anniversary of Holy Apostles Church, 1972. Images from the second two

sources are reprinted by permission. They are the

property of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin

and may not be reprinted without permission.

|

Grave of Rev. Edward Goodnough |

Grave of Rev. Cornelius Hill |

Holy Apostles Church, July 2005

Holy Apostles Church viewd from the Churchyard

July 2005

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller,

Coe College, with help from Linda Heller, research assistant;

Betty Rogers and Harlene Hansen, Reference, Stewart Memorial

Library, Coe College; Jane Henning, Grace Episcopal Church,

Madison; Judith Jourdan, Oneida Tribal Genealogist; Kathleen

Petersen, Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College;

Louise Pfotenhauer, Neville Public Museum, Green Bay; Jean

Wentz, Archives Assistant, University of Wisconsin, Green Bay;

Carla Zecher, Director of the Center for Renaissance Studies,

Newberry Library.