Main Contents & Search

.

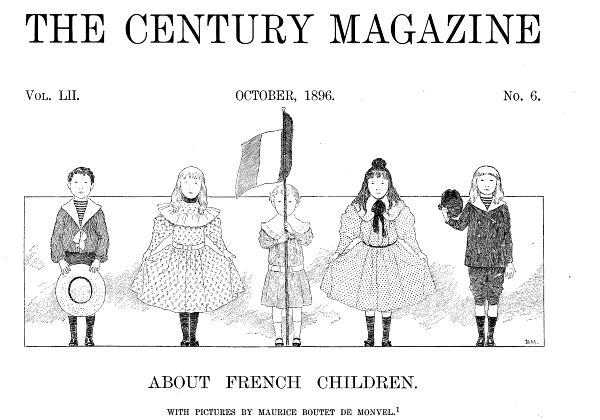

ABOUT FRENCH CHILDREN.

WITH PICTURES BY MAURICE BOUTET DE MONVEL. (1)

Th. Bentzon / Madame Blanc

A possible Jewett translation -- Introduction

Marie Thérèse de Solms Blanc and Sarah Orne Jewett became

acquainted by letter in the mid 1880s, when Madam Blanc, writing

under the name of Th. Bentzon, wrote a long, positive review of

A Country Doctor (1885). Jewett met Blanc during a trip

to France with Annie Fields in 1892. Blanc visited the United

States in the following year, doing research for her book, The Condition of Woman in

America (1895). In Sarah Orne Jewett, Blanchard

says that during this stay and later, Jewett helped translate

into English and place several of her essays. In Sarah Orne Jewett Letters (Cary)

are letters (77 and 78) regarding "Family Life in America,"

Jewett's translation of a portion of The Condition of Woman

in America, which appeared in the Forum, XXI

(March 1896), 1-20. "About French Children" is among the essays

Blanc placed in American magazines during the mid-1890s. It

appeared in Century 52:6 (Oct 1896): 803-823.

ABOUT FRENCH CHILDREN.

WASHINGTON IRVING has often been accused of saying that little dogs and children were influential members of French society. It is quite true that in the United States I never noticed that close and sentimental intimacy between human beings and quadrupeds so frequently seen in France. American life is so active, so desperately crowded, either usefully or socially, that perhaps it does not permit the loss of time inevitably brought about by friendly intercourse with a dog. As for children, I believe that their importance is equally great in all countries; but it asserts itself in a more noisy manner in America than anywhere else. Everything is sacrificed to them, for they represent the future, which is all that counts in a country whose past is very short, and whose present is a period of high-pressure development. Yet no one must suppose that, before presenting an apology for French children, I intend to malign American children, as certain travelers have taken the liberty of doing very thoughtlessly, although they had met them only on steamships, cars, or at hotels, enjoying a holiday with that buoyancy which is the characteristic mark of the whole race. I have known some who were very well brought up, even from our point of view, and among those who were not I have admired precocious sense, vivacity of mind, quiet determination, and capacity for self-government, qualities which I should wish for all ours.

I would now beg you to consider the less pronounced persons of our little boys and girls, who are required, above all else, to be aimable in the sense the word has in France, where it means lovable, having nothing of the lukewarm and hollow meaning of the English word "amiable." The aim of their education differs in the two countries. In America good parents have but one thing in view -- the rational development of individuality and of responsibility; while this, in the girls' case as well as in the boys', is the constant labor of parents in France -- to keep their children in tutelage, to prevent them from seeing what is going on outside, and to give discipline and complete submission the first place. In fact, their children are being more specially trained for the exigencies and the accomplishments of a social life whose machinery has been running on for centuries, while Americans are being prepared for individual struggles such as they must necessarily make in a new country.

In France every young mother, to whatever class she belongs, may say, in speaking of her baby's outfit:

Au poids des écheveaux usés

J'avais mesuré ma pensée

Sereine entre les fils brisés

Et chaque fois recommencée. (2)

I know nothing more perfectly French than this little piece of

humble and exquisite poetry, showing the stitches that keep a

dream imprisoned so purely in snowy linen; nothing more motherly

than the last wish of the careful embroiderer, who bids a bird

building its nest pick up bits fallen from the finished work,

and mix them with its own materials, so as to keep and protect

the impatient wing that is growing. That growing wing is

threatened with many an embroidered and beribboned bond both in

the present and in the future, yet less hedged in than in the

past, since people have begun to bring up their children more

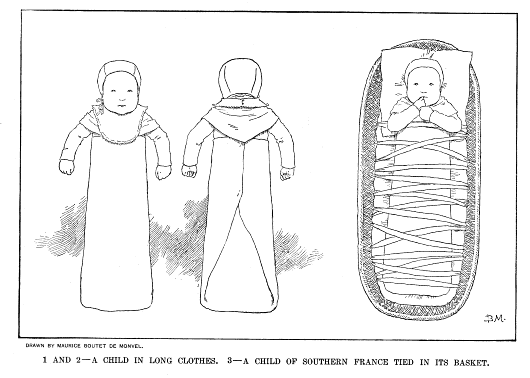

according to English notions. The swaddling-clothes are no

longer as tight-fitting as a sheath; the cap which covered the

bald little head, and framed it so prettily with its ruche, has

been given up; the lace pillow for the lolling head to rest on

has been banished: yet, in spite of all this, the infant in the

early stages of its life is a sort of bundle, very much like a

bolster, from which two arms and a wrinkled little face

protrude. The advantage of this system is that the child is very

easy to handle; but it has its critics, who maintain that the

natural condition of the spinal column is not a straight and

stiff line. Paris has made many concessions, and the swaddling

is less rigid; but the provinces have not followed suit, while

in the country everywhere new-born infants are tied up as hard

and fast as ever. In the south of France they go to the length

of putting this papoose in the bottom of a basket, where it is

kept in place by strong bands passed zigzag from head to foot.

This is how we prepare our sons for making use of their liberty.

However, leading-strings have been given up; that is one step

toward progress. Twenty years ago they were still considered

indispensable, -- at least, country people thought so, -- and

there was no end to their intricacies.

|

|

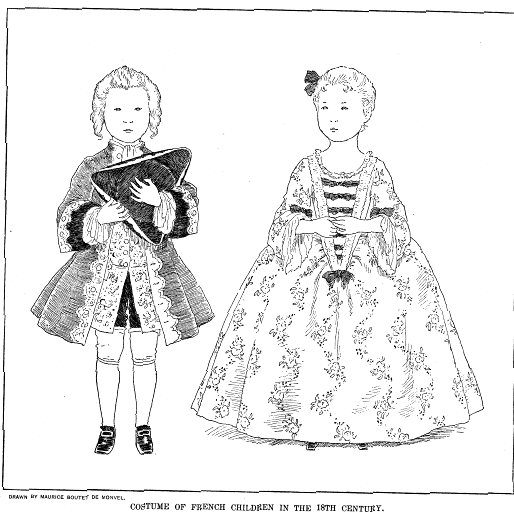

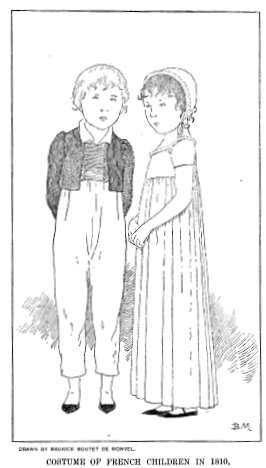

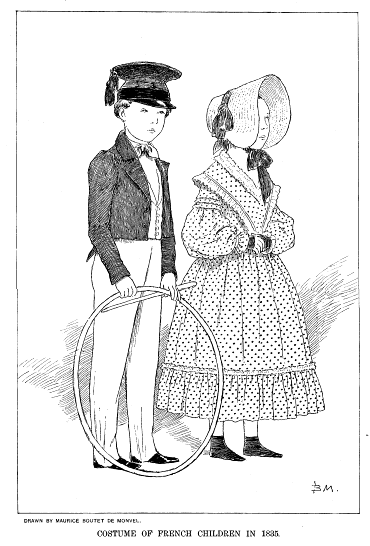

It is quite remarkable that swaddling-cases, bands, and various other fetters are the only essentially French contributions that have ever been made to a baby's equipment. Although fashions in general have for centuries been promulgated in France, clothing every one à la Française, yet the fertile imagination which could do this stopped short at children's clothes. Look at the paintings and engravings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and see the little creatures who, as soon as they gave up their plumed bourrelets (3) and long tulle aprons over a blue or pink dress, against which a jewel hung instead of a teething-ring, had to wear uncomfortable costumes, the miniature reproductions of their parents' clothes. Little girls, particularly, were put into whaleboned bodices and sumptuous robes, which necessitated lessons in deportment to be properly worn, and consequently the dancing-master was one of the first professors employed. It needed the revolution of simplicity brought about by the influence of Jean Jacques Rousseau before children could be comfortably clothed -- girls in muslin slips and heelless shoes, boys in short jackets borrowed from English styles. Ever since then we have followed English fashions for our children, and now America lays down the law, with its blouses; its quilted, somewhat oldish winter coats reaching to the ankles; its pretty Puritan caps trimmed with fur, a thousand times preferable to the immense, caricature-like bonnets copied after Kate Greenaway. But I am anticipating; we are still at the swaddled infant's long cloak. In every Catholic family infants are consecrated to wear white; that is to say, placed under the protection of the Holy Virgin by a vow which does not permit the child to wear any colors but blue and white, those of the patron saint, for a fixed period, usually a year or two, sometimes longer in the case of a girl. This must be some remnant of chivalrous times, of service professed by a knight for his lady when he wore her colors, for it is not, properly speaking, a religious tradition.

The birth of a new citizen in France at once gives rise to countless formalities, and an avalanche of legal scribblings, which would teach him, could he but understand, that his country is par excellence the home of legal ceremony and administration. Within the first twenty-four hours notice of the birth must be sent to the mayor's office (there is such an office in every village in France), so that the official physician may call and make the necessary legal statement. I suppose he wants to convince himself that the declaration already made was correct, and that the family, when it announced the birth of a girl, was not trying to screen a future soldier from his compulsory service. Then the father, accompanied by two witnesses, goes to fill out the birth certificate, and give his child its legitimate, documented position, to which he or she will be obliged to have recourse in all the great, and frequently in the minor, circumstances of life, from one end of it to the other. Without it the child could not enter a school, nor draw lots on entering the army, nor get married, nor be buried. The least mistake of form would have most serious consequences; the baptismal names declared must always be placed in the same order on all future deeds. These are usually saints' names. I recall the amusing anger of a young American father of my acquaintance, who wished to give his son born in Paris the name of the great sailor Duquesne, in remembrance of the avenue where the baby had seen the light of day, and in addition the family name of one of his friends, which no Frenchman could pronounce. All this seemed so shocking and incongruous to the registrar that the certificate was made out only after an interminable discussion.

At last our bantling is labeled, registered, catalogued, classed in its place in that closed and guarded society where each one of us stands on his square like a figure on a chessboard. It has not yet breathed the fresh air; its first outing is usually for the sacrament of baptism. Carried to church in sumptuous robe, its sponsors renounce Satan's works and pomps in its name, while its forehead is all wrinkled by crying as the holy water trickles on it, and its little face all screwed awry the salt laid on its tongue. This ceremony, performed before the assembled family, is a very simple one in Paris and all large cities. The godfather gives the godmother a present, another to the young mother, and invariably presents his godchild with a silver mug, fork, and spoon. Sugared almonds in ornamented and gilded boxes bearing the child's name are distributed to friends, but that is all. The plainest peasant baptism has a much more solemn stamp. It never takes place without a great feast; the file of guests walking to church behind the godparents, arm in arm and two by two, is as imposing as a wedding procession. And in this respect matters take the same course at the chateau as they do on the farm. There is great ringing of bells, a feast, and showers of sugared almonds mingled with pennies for the village urchins. The baby's nurse, overwhelmed with gifts that day, is the heroine of the festival.

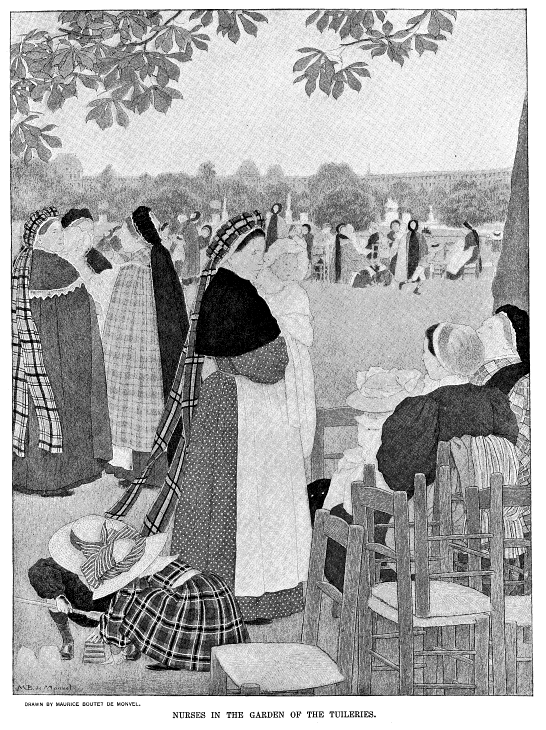

There is nothing more aristocratic, and at bottom more inhuman, than the institution of the hired wet-nurse. Institution is the correct word, as the office for nurses is under official management, and controlled by the Board of Public Charities; but this does not prevent private undertakings of the same nature. The peasant woman who wishes to make a business of nursing comes to town with her by infant, and goes to one of these offices. Her employer pays for the forsaken baby's journey home.

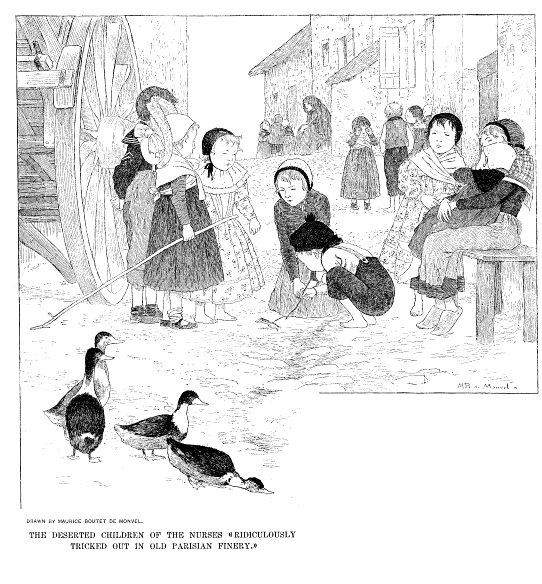

As to what becomes of the nurse's family during her absence, -- in order to appreciate it, one must visit the poorest part of Morvan (4) where this peculiar profession is principally carried on. When one sees the squads of superb, buxom Burgundian peasants on the Champs Élysées, adorned with dazzling white aprons, crowned with brilliant ribbons, dragging their long cloaks in the dust, one little dreams what they have left behind them: a sordid hovel, where, while the father drinks more and more in the public house to forget his loneliness, the neglected children crawl about, not only dirty and unwashed, but ridiculously tricked out in old Parisian finery, belonging once to their foster- brothers (fréres de lait), and which they wear even in tatters, hind side before, and upside down, the "looped and windowed raggedness" of former magnificence -- the worst of all!

Formerly children of the best families were sent out to nurse, as shopkeepers' children are now. The sons of country landowners, nursed on their own estates by farmers' wives, often stayed on a year or two after they were weaned, sharing the rough life around them, which if they could bear it made them very vigorous. I form my opinion of this by the samples I saw in my youth of men born before the Revolution. Once the child returned from the country to its family, it was placed, according to its sex, in the hands of either a governess or an abbé, such as are still found in the old families of the Faubourg St. Germain. More frequently then than nowadays little girls began to study Latin with their brothers. Now we have the foreign nursemaid, who takes the child when it is just beginning to lisp, and before it knows how to speak its own language well. At present an English or German nursemaid is to be found in every well-to-do family.

Physically the French baby resembles the American much more than the English baby. Ours are not magnificent lumps of pink-and-white flesh dimpled all over; being agile, wide-awake, and mischievous, they are not as shy as English children; still, they lack the precocious assurance of the American child, who is afraid of nothing. No one goes into ecstasies over them, although, in fact, they are adored; they do not feel that they are the rulers of the household. They soon learn to keep their place, and seem to understand that though their mama may give herself up to them entirely, they are not equally interesting to the remainder of the world. If called to the drawing-room, they come in washed and combed, bow politely, and leave before becoming tiresome. They are not allowed to come to the table, even in the strictest intimacy, until they can behave properly, be silent, and commit no awkward blunders. They are forbidden to ask for anything, but this does not prevent them from getting whatever they want.

It is needless to say that we teach our children not to sop up their sauce with bits of bread, not to gulp down their soup audibly, and not to eat with their knife; but we specially require that they should not leave anything on their plate after having accepted it from the dish. It is not the waste alone; it is the absolute impoliteness of the act, which consists in a guest leaving half of what he has been helped to untouched, under the anxious gaze of the hostess, who naturally supposes that nothing is to his taste. From the moment our children know how to handle a knife and fork they are told never to express an opinion, favorable or the reverse, as to what they are eating, and to eat everything put before them. The habit clings through life. In general they do not try to attract attention, do not express opinions, are not as loud and noisy as American children. Their sayings, their clever tricks, are not quoted, and what is feared more than all is to make them consider themselves important. Although their health is carefully watched, yet their guardians do not constantly experiment upon them with the newest hygienic methods. Instead of trying to develop the principles of causality as early as possible, we usually advise them not to be asking questions perpetually. Passive obedience is indispensable, without questioning the command, and extreme politeness toward servants is strictly enforced. Needless to say, there are many breaches of the law, but there are also many punishments, which, I must admit, they sometimes take with a certain amount of cynicism. Here is a quite recent example. A young gentleman of five followed his mother, who was looking at an apartment with the view of buying it. "I think," said the lady, after her examination, "that this will suit me." "Oh, no, mama," said the little boy, breaking in, "it's impossible; there 's no dark closet closet! Where could you put me when I'm naughty?"

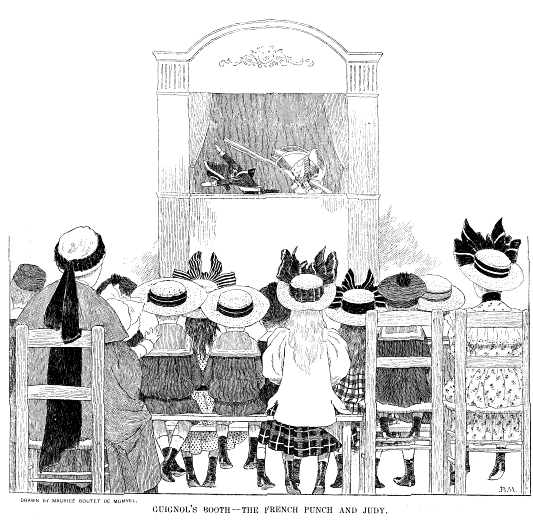

If I wanted to show off an assemblage of French children to their greatest advantage, it would be neither at one of those fancy-dress balls where, once a year, during carnival week, the favored ones make the most of their dancing-lessons nor at a Christmas or New Year's gathering, to which they bring that frank but prettily disciplined gaiety, preferred by us to overflowing animal spirits, which, indeed, do not form a part of our national character at any age. I would rather have them seen on some fine, balmy spring day in the Champs Elysées, in front of Guignol's booth.

It is rare for little boys and girls, even when they have been taught together, to continue associated after they are eight or ten years old, and this period is often shorter. The former play with soldiers, the latter with dolls; the various rights and duties of the two sexes begin to assert themselves. After the first communion, when girls are eleven, boys twelve years old, the separation grows wider day by day. This is the time when religious fervor begins to dominate a young girl's life, while with boys it frequently begins to lessen under the influence of secular instruction, and, above all, by the father's example, so often most unconsciously set.

Innocence, meaning absolute ignorance, is preserved in children as long as possible. As for myself, I believe that the veil of mystery systematically thrown over too many natural things serves only to stimulate curiosity, just as lessons in modesty and propriety in speech at an age when the very knowledge of evil does not as yet exist are often dangerous. We wish our children to have eyes and not see, to have ears and not hear; we forget that the very precautions we are constantly taking as regards them, by means of smiles and implied meanings, may teach them much, and in an unfavorable way, by making them think that certain secrets most important for them to discover are hidden under the falsehoods we tell them, whose absurdity they perceive much sooner than we suppose.

Reading the Bible seems to me, in many ways, a very happy initiation for Protestant children; they gain by learning the Old Testament directly, instead of the rather childish narration given in the greater number of our abridgments of sacred history. In the Bible, by means of elevated poetry whose austere candor enlightens without exciting their imagination, God is forever present between them and the facts that from all times have represented life.

However innocent she may be, a little French girl is much more of a little woman than a child of any other nationality. She does not romp; she is demure and quiet in her games, which are often imitations of a grown person's life. She is trying to learn how to be the mistress of her house by means of her dolls, furniture, kitchen, and dishes. Feminine arts are still a part of every well-arranged French education. Men really care more for these accomplishments than for others, as they make stay-at-home wives who look after their households; and as a French- woman's principal aim is to please her future husband, every mother prepares her daughter for this end. This is why she does not permit too close an intimacy with little boy-cousins, because ten years later a jealous husband would take a dislike to these friendly cousins; nor would he like his wife's bosom friends, in whom she confides, and who never leave her any better. Mothers, therefore, permit few if any intimacies, and these are all winnowed and selected with the greatest care. One advantage of this system is that the name of friend is not carelessly bestowed right and left; it takes time and good reasons for simple acquaintances to rise to that rank. The mother not only wards off little boy-cousins and intimate girl-friends, but she discourages the little girl in showing off her knowledge out of the class-room, for she is fully aware that nothing could be less attractive in the eyes of the expected lord and master than a blue-stocking. A bright little girl I could name had, by chance, picked up some astronomical scraps, together with other scientific facts, which allowed her to shine now and then. One evening, while playing in the garden, she heard a friend of her father's exclaim, "What a dazzling star!" "That is not a star, sir," she said; "it is a planet." Her mother was in despair, for she would rather a hundred times have found her ignorant than have seen her "show off" or capable of committing the enormity of contradicting an older person. "I hope," she said jestingly, as a sort of excuse, "that when she is eighteen the poor little thing will have forgotten a great part of what she knows to-day!"

Among us it is not only a woman's duty to please: she does it by

instinct; the tiniest girls do it unconsciously. Just watch them

as they walk in the avenues of our public parks; they have all

the unstudied grace and ease of real ladies, and, indeed, they

fully suspect that approving eyes watch them as they skip the

rope; for coquetry, which is much more subtle and more delicate

than flirtation, less direct, too, in its aim, is innate with

them. They are not ambitious of winning the admiration of boys

of their own age; they look down with disdain on such admirers;

they aspire to please big people. In their intercourse with

little playmates there is a great deal of ceremony. Nothing

could be more amusing than the manner of a little girl who,

having come to the conclusion by the general appearance of

another little girl that she is worthy of the honor she is about

to confer on her, finally asks her to play at hide-and-seek. If

some brave young person walks up to a group of players with the

time-honored phrase, "Mademoiselle, will you allow me to play

with you?" a sharp and comprehensive glance at once decides

either the reserve or the warmth of the reply. Matters would

hardly take a different form in a drawing-room in the case of a

more serious introduction. The gestures, the bows, the little

looks, the smiles, are copies of their mama's; and yet they are

all perfectly natural in the sense that they are merely

following their own nature, without a trace of that

self-consciousness that "puts on airs" of any kind. This

Anglo-Saxon quality of self-consciousness, in both its good and

bad points, is incompatible with the French temperament.

Literature in our country, not having as its aim either instruction or amusement, but the production of works of art, is forbidden to French children. I except fairy-tales. Perrault has written masterpieces; Mme. d'Aulnoy and others have followed him; the fairies of other countries may have been more poetic, but they have never been as witty as the French. Leaving fairy-tales aside, children were obliged for a long time to be satisfied with the very slight collection bequeathed by Berguin, Bouilly, Mme. de Genlis, those clever people who know how to coat a moral lesson with a thin layer of pictures, as bitter pills are coated with sugar. In fact, this is the French parents' very ideal in the matter of story-books, and to please them the lesson must not be too well coated, or hard to find, for the spirit of investigation is not encouraged in young readers.

During the past twenty years, however, the meager library at their disposal has grown wonderfully; celebrated pens have contributed toward it; we need but mention Jules Verne, whose scientific fairy-tales have, alas! almost completely dethroned those that appealed to the imagination alone. But neither in his books, nor in those of any of his competitors, will you ever find what both English and American writers currently permit themselves to do, namely, to arraign a relative, as, for instance, the wicked uncle in "Kidnapped," or to make teachers hateful, or merely ridiculous, as is the case in Dickens's works. This would be an outrage upon the respect due them in the aggregate. For this reason translations are nearly always expurgated. The friendly adoption of poor Laurie by the four girls in "Little Women" would be considered very unseemly. Yet, for all that, they were good little New England girls. T. B. Aldrich's "Story of a Bad Boy" was deprived of one of its prettiest chapters, the one about his childish love for a big girl. "It is useless," they say, "to draw attention to that kind of danger." Authors and editors are often greatly perplexed before this severe tribunal of French parents. The difference between the books children are allowed to read in France and those sought by their elders, the contrast between the tasteless pap on one side and the infernal spiciness on the other, must greatly astonish both English and American readers, who nearly all accept the same literary diet, young and old, parents and children.

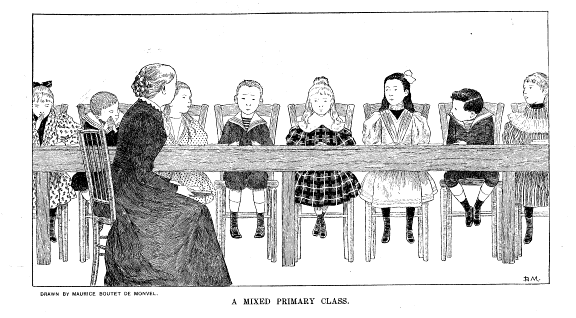

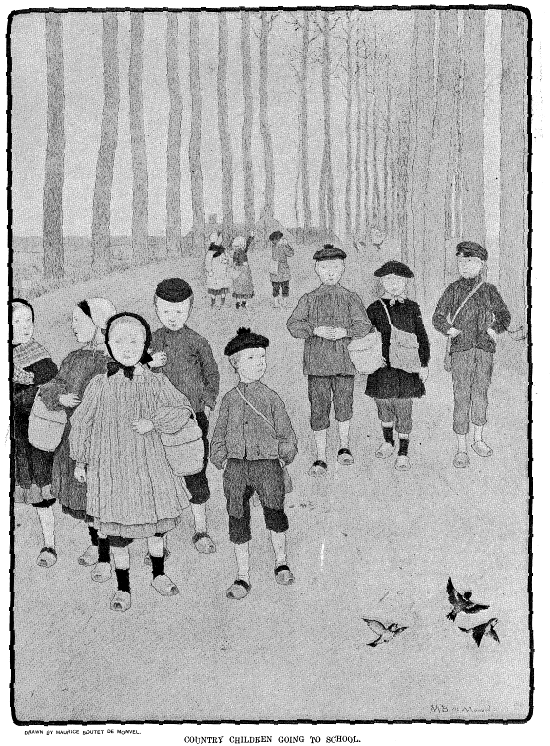

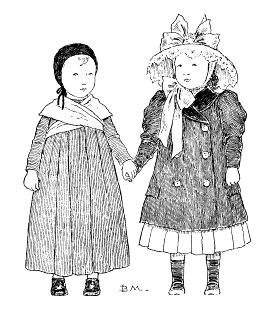

As in all other countries, I suppose, French boys lag a few years behind the girls, at least during childhood, so far as intelligence and industry are concerned. In the mixed primary classes boys and girls meet twice a week before a lady teacher, who gives them elementary instruction. As a rule, the girls carry off all the prizes; this causes their masculine comrades to long, with a vague feeling of humiliation, for the day when they can go to a lycèe, where there will be no girls, and where they will be led by men, and think and speak and act like men themselves. These classes (cours) for little children of both sexes have been in existence only a few years, and are the nearest approach to co-education that has ever been made in France, at least among people in easy circumstances; for certain poor villages have had, and still have, mixed schools, and even in the villages where there is both a male and a female teacher, one always sees the school children come and go along the roads together; little brothers and sisters, as well as little neighbors, both boys and girls, carrying baskets on their arms, and bowing politely, even though they do not know you, saying, "Good day, sir," "Good day, madam." They often have to go great distances to reach their school, which they must attend until they are twelve years old. Our French peasants would never dream of dotting the country with school-houses, and keeping them up at their own expense, as the farmers do in America. It is even hard enough to get them to do without their children's help during the summer months, when the harvest needs as many arms as possible. As soon as he can walk, the little peasant, armed with a switch, takes care of the geese and turkeys in the fields; next he is advanced to the grade of cowherd, with the result that, even in this era of supposed compulsory instruction, he is not much more learned than his parents, who were never taught anything at all.

As a general thing, however, all our future voters know how to read. In consequence, the picturesqueness of rustic life is fast disappearing, although there is still much left.

There are always a few foundlings among these little country school children. They are sent to farm-houses by the directors of asylums, and they continue to look after them so as to assure them proper treatment. Most frequently these poor little waifs scattered through France come to be considered members of the family, and they have had the honor of being immortalized under the old name meaning "forsaken in the fields" by the greatest of pastoral novelists, George Sand. If you care to know them well, read "François le Champi." This might be the place, if there were room, to show the working of those nurseries where the children of the poor are suckled by an army of wet-nurses, and of the Society for Maternal Charity, which goes back to Marie Antoinette's time. One ought to make a picture of that clean and rosy multitude which crowds the infant asylum from the time the little ones are three days old, and then the infant school to their sixth year, while their mothers, all industrious workers, are earning their day's wages. One ought to mention the orphanages, the best of which in these times of unwholesome centralization are the agricultural orphan asylums directed for the greater part, as well as those of the cities, by religious brotherhoods and nuns, the latter frequently having the charge even of boys. In spite of the growing emulation of the lay element in the last twenty years, the good sisters still hold the first rank. There can be no better directresses of industrial schools and women's work bureaus, of asylums of all kinds. Their influence in reformatories and houses of correction for the young is incomparable. And this influence does not depend alone upon their wide experience, or the absolutely disinterested motives which make them serve without pay or human ambition, but on the authority their dress lends them, a dress that represents centuries of devotion to the same task. Among them all the sisterhood of St. Vincent de Paul stands out in most brilliant relief -- those white-hooded angels who move about the streets of Paris in such numbers in the service of the sick and the poor. Their popularity has remained as great as ever through the clash of revolutions and the progress of free-thinking.

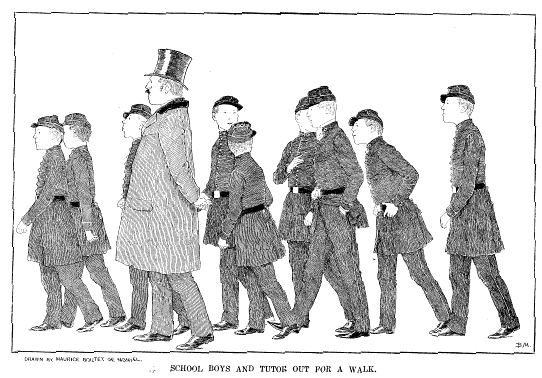

Nothing must seem stranger to Americans, accustomed to see school-boys of all ages come and go freely through the streets, dressed according to their parents' taste and means, than to watch those long lines of French boys, sometimes nearly grown to manhood, wearing a school uniform of semi-military coats and caps, and led out for a walk like a flock of sheep by a shepherd. Their uniform is worn without any pretension to strict regimental regulation; the little fellows look ridiculous, as their brass-buttoned coats are generally too long and ill-fitting. Their sole care seems to be directed toward playing the worst tricks they can on the usher who is leading them. School-boy slang dubs this overseer a pion, a chess pawn, and there is no more perfect example of a butt than this subaltern functionary. His tyrannical supervision, his power to inflict punishment for the slightest peccadillo, necessarily make him hated by those whose words and least actions he watches during recess as well as during study hours. If the usher is vulgar or coarse at times, the boys are in general far from having good manners.

These young fellows, varying from eight to eighteen years of age, are shut up all the week in a real barrack, a most rigorously closed one at that -- "a great stone box, entered by a single hole, provided with an iron grating and a porter," as Taine has said. Here Latin, Greek, history, and mathematics are poured into them without respite eleven hours at a stretch, and with very short intervals for recreation in almost treeless yards, darkened by high walls, and affording too little space for their games.

Strangers, when informed of this kind of life, begin to notice a peculiar pallor, and the look that comes to children and plants deprived of sunshine. The greater number of our most powerful men, from the intellectual point of view, were formed under this school regime, and at a time when it was much harder than it is now; for the quality of the food is better, without yet being quite sufficient -- if one may judge by the avidity with which the present school-boy falls upon the supplies brought him by maternal solicitude on visiting-days. As of yore, the roll of a drum awakens the poor wretches at five in the morning in the long dormitory, where forty or fifty beds face each other in two long lines from opposite walls. There are as many beds as pupils in a class. No one, of course, has ever thought of warming a French dormitory. The boys dress hastily, shivering the while, and one may suppose that their ablutions are somewhat summary. In our schools little thought is spent on anything but the brain, and one must grant that the seclusion they offer favors its development. English and American youths have more robust bodies, and this gives tone to their character; they are more harmoniously balanced, and much happier. They are vigorous plants grown in the open air. A young Frenchman is a forced and precocious hothouse growth.

The colleges under the control of priests, leaving aside all question of knowledge, have always been celebrated for the care given to hygiene, bodily exercise, and a semi-paternal education. They have gone ahead of the revolution now being slowly brought about in other colleges. The greater part of them are systematically located a little way out of town, so as to obtain the best sanitary conditions. The Jesuits were the first to inaugurate vacation trips for their pupils.

Boys' schools, both secular and religious, differ among themselves, both in spirit and in tendency, far more than they do in the United States, and the stamp each one gives is deeply impressed upon all who receive it. For instance, the pupils of the Brothers of the Christian Doctrine, and those of the district schools, are drawn from the lower classes. While the district-school boys assert the principles of equality, with which they are imbued, by their monumental insolence, the others still have a notion of what is meant by deference and respect.

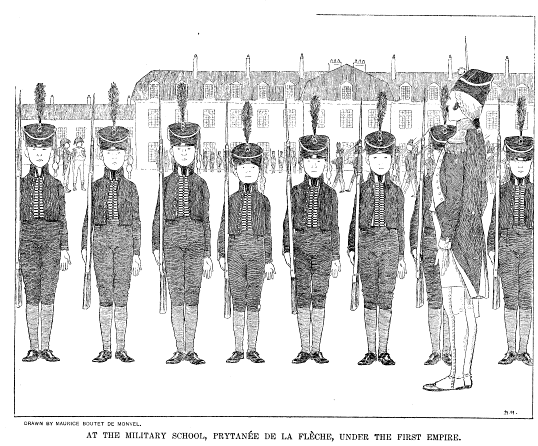

While speaking of disciplined and regimental schools, it would not be quite fair to omit the Prytanée de la Flèche, the only one of the many military schools of the pre-revolutionary period still extant. Here the sons of officers who have died in service, or who are simply poor, are gratuitously prepared for St. Cyr, the military college. They are miniature soldiers, like the children of the troop, (5) with this difference, that they receive a good classical education. I remember the anecdote my stepfather, Count d'Aure, who entered La Flèche (5) the regulation age of eight, used to tell me. It was the first time he had left his mother, and he was somewhat bewildered by the roughness of his comrades, who affected the airs of old troopers. To make sure that he was not a milksop, one of them, a veteran of twelve, made him lay his hand flat on the ground, stepped on it, and crushed one of his fingers. This tormentor was the future General Baraguay d'Hilliers. The victim, who nearly fainted, bore it bravely, however. "And this was the beginning, my stepfather used to add, half a century later, when showing his deformed finger, "of a friendship that lasted all our lives." This happened shortly after the First Empire, when Roman virtues were emulated; but one must not infer from this isolated fact that stoicism flourishes vigorously in the French educational system. During many centuries it was not its aim to prepare either pioneers or those great business men who are more tossed about on the ocean of speculation than a vessel by a tempest. With the exception of the roughness and servitude of barrack life, the sequel of the inflexible discipline of the college, a Frenchman leads the easiest kind of life, one that demands the least amount of effort. Even while quite young our children know, or think they know, that their lot in life will, if they choose, be the same as their father's, who, being the guardian of an inherited fortune, will surely with leave them a prearranged position.

This father has full and complete authority over them, and demands strict forms of respect. In France a good son subordinates the important acts of his life to his father's consent, even more than he should in some cases. On the other hand, the blind and tender desire that all parents, without exception, have of keeping their children near them, of not letting their sons wander about the world, or risk the patrimony of their ancestors, has brought about a mania for finding employment in government offices in preference to embracing a liberal career. The whole nation has the same stay-at-home and exclusive tastes. This permits foreigners to bring France all that is worst among them, while it does not send her sons to seek the great and good things there may be in other countries. If a life of perpetual wandering finally becomes useless and sterile, it is equally true that it is debilitating and unwholesome never to have a change of air. Frenchmen do not seem to notice this.

These bonds are still more closely drawn about young girls. How many mothers say to you, when speaking of their twenty-year-old daughters, "I have never left her for an hour either by day or night"? And there is scarcely an exaggeration in the statement. But how about school years? Most frequently nowadays there is no school. The friction of public life, considered so necessary for boys, is in general found harmful for girls. I have already said that in the harmonious and complicated play of French society, men and women have two very distinct parts to play; they are separately introduced to it, the son by his father, the daughter by her mother, who guides her in the path she has pursued herself. The exaltation, I might almost say the exaggeration, of maternal self-sacrifice is especially frequent in the great middle class. In the higher ranks, the Frenchwoman remembers that she has social duties to perform, that she must keep up the reputation of the salons of her country, which the trivial custom of reception-days has so much lessened, and that if she is forever busy directing and correcting her daughter, she runs the risk of being no more than a nursemaid at first, and a governess after that. Besides, it is proved that in all aristocracies, whether of wealth or birth, women are not disposed to give up worldly pleasures, and the governess-mother is obliged to sacrifice these pleasures for the greater part.

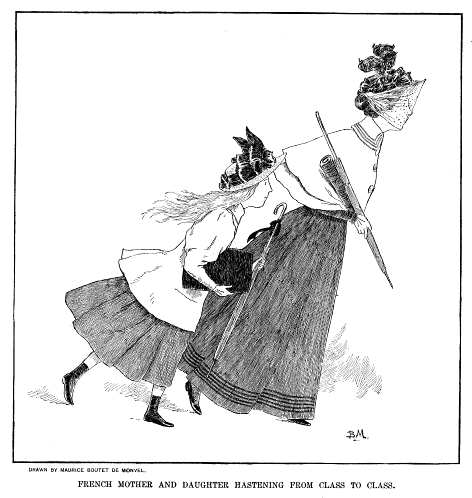

When the mother who educates her daughter by means of the private classes (cours) almost universally adopted here has been busy with two or three children of different ages, or even with a single one, rushing from a music to a drawing class, from a singing to a gymnastic class, and thence to a dancing class, -- when she has been regularly present at the weekly lectures on history and literature, not to mention the catechism class, where religious instruction is indefinitely prolonged for years after the first communion, -- she is worn out with fatigue, and at night, instead of going into society, is quite ready to stay at home with her daughter, whom she would not leave alone under any pretext. And to whom could she trust her? Sometimes there comes to relieve the mother a governess in the form of a perambulating teacher, in whose company the big or little girl goes walking, visits historical monuments and museums, meanwhile gathering some knowledge of English or German on each trip. There may happen to be a grandmother in the house, or some old relative whose duty it is to watch over the daughter; but, at all events, social life is much hampered for the mother by her presence, as it kills conversation, which in France is rarely intended for juvenile ears -- not so much on account of the license which it would be better to suppress (as people in whose countries conversation does not exist in an artistic form take pleasure in saying), but for reasons of quite a different kind. The liberty of discussion and thought, the vivacity of repartee which constitutes so much of its merit, presuppose minds at once ripe, enlightened, and alert, and equal to the acceptance of paradoxes -- a plane which young girls are not supposed to have reached, and will reach but gradually, things coming to them, as it were, filtered by maternal circumspection. If this mother who molds her daughter in her image is a remarkable woman, the result may be perfect; otherwise it would be preferable to send her to boarding-school. But one must believe that there are many able women in France, for if you succeed in making that almost mute little person who can listen so well talk to you, you will often be surprised to find that, although she has not traveled much, not read everything, -- far from it, -- not been to the theater, except to see a classical piece or hear some music, she nevertheless has guessed or understood very much. You will be specially apt to notice how few silly things she says. No doubt there is but little method in this style of education; much has been done by fits and starts; but the public lectures at the Sorbonne will crown the edifice and fill up many gaps, as these lectures are of the highest order, and are well attended. I am willing to grant that even the most complete home education is not the best means for winning a diploma; but diplomas do not dazzle us. Even those who recognize their utility admit that there is another essential point, and that an abiding taste for study is better than all else. Without it a diploma is but vanity and sham. Besides, there are many girls brought up at home or in convents who pass their examinations victoriously, too. In France one is not graduated in one's own college, but at the University, by unknown examiners, who do not ask you where you learned what you know, provided you know it. I hear clamors raised: "But all comradeship is missing! The mother and daughter must become too indispensable to each other by this means! There must be much egoism in the tender dependence of the daughter who is so accustomed to turn to this maternal providence for everything that concerns her!" This is indisputably true. "And what of charitable works -- public works? What place do they hold in all this? You have told us nothing about the interest taken in philanthropic or sociological questions by this mother and her daughter." As for charity, it is still taught our children under the simple form of almsgiving.

To show the transformation that woman's education has undergone in France, and to indicate as clearly as possible what still remains of the old forms, and what new ones the future promises, I ask permission to go back to the last century, when a little girl, far from being her mother's inseparable companion as she is now, was merely brought to her once a day by her governess. When eleven or twelve years old she was taken to a convent, where, we are told, she acquired "the accomplishments necessary to the status of a woman who is to live in society, hold a certain place there, and even manage a household."

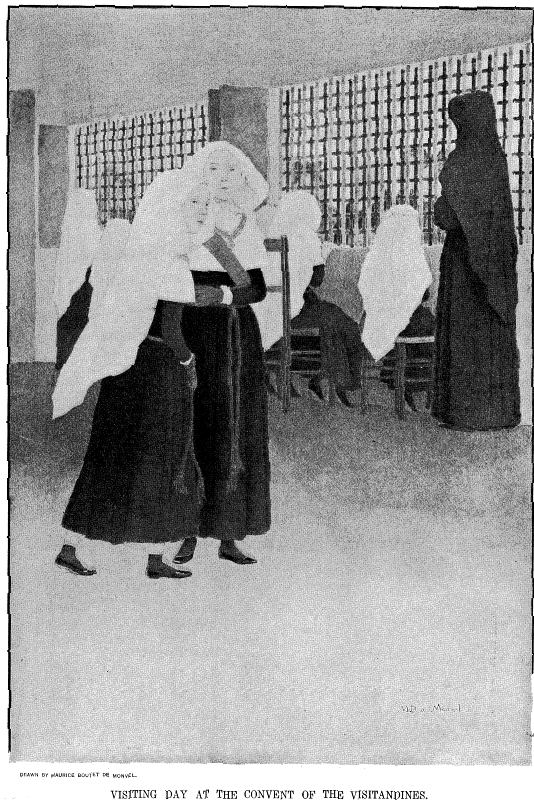

This may seem very extraordinary to those who imagine a convent as a prison or a tomb, but it is certain that the unchanging convent has remained just what it was when Rousseau was both praising and blaming it. The boarding pupils still play many games and have plenty of exercise, and the result is that they are usually in very good health; the calm serenity of the moral atmosphere surrounding them seems to preserve them from all nervous excitement. Besides, the convents -- and I refer to the great convents such as the Sacred Heart, the Roule, or Les Oiseaux -- are still the places where women are best prepared for appearing well in society. How is this done? By keeping up old traditions, the special formulas of a fortunately vanished period when a young girl left the convent only to be married. She was then at once supposed to ignore no single shade of etiquette, to do nothing awkward, to be armed from head to foot for the grand ceremony of her presentation at court. These may be puerile formulas, but they separated one, once for all, from the common people, and they are still preserved behind those great walls that immure the past. In addition, the nuns who are the guardians of these traditions frequently belong to aristocratic families. This atmosphere of hostility to all progress, this silent protest against both the good and the evil of modern times confounded in the same tacit reproach, are the convent's worst features. It would seem like a scene from the middle ages if an American Protestant could see the parlor of the celebrated convent of the Visitandines, where little girls come to talk on Sundays to their relations behind a double set of narrow gratings. Not all convents are cloistered; there are some where no grating separates parents and children; but there is always a nun walking up and down, discreetly present at all interviews, and all letters sent or received must be read by the superior. Save during the two months of vacation, the separation between mother and daughter is complete, and this is why in the present time, when home education seems to prevail, the convents are less in favor than formerly.

They, however, have numerous partizans in the provinces, which -- and one cannot make this too clear -- are not at all like Paris, and even in Paris, where nearly all the young girls of the Faubourg St. Germain spend some time au couvent, if only for the sake of tradition. I am ashamed to say that in republican France many vain people, who wish grand acquaintances and a certain style for their children, place their daughters in these "nurseries for great ladies" just as they elect to intrust their sons to the Jesuits. To this double category we can add the militant Catholics who consider it their duty to protest against college instruction because it is said to be godless, and the many others who are behind the times, and think that high instruction is for men alone. Let me add that the nuns are now obliged to have their diplomas before they may teach, just as well as simple laywomen.

If I say less about lycées for girls than about convents, it is because they are so much more like the schools in America and England. They are day boarding-schools, where the most skilful professors lead young girls up to taking their degree of B. A., if they choose, the study of dead languages being optional. There is still much prejudice against them, but about thirty years ago there was just as much against the Sorbonne lectures, founded for girls by the great minister of public instruction, Victor Duruy; eighty bishops thundered against them, yet to-day everybody accepts them.

The gravest accusation against girls' lycées by the group of retrograde thinkers is that they are "badly made up." Good society still holds aloof, but begins to understand that the absence of religious instruction does not by any means imply systematic hostility to faith; for parents, and the church they belong to, are at liberty to develop this, and the necessary time is allowed for it. The war on these recent establishments is, in short, a partizan war. Lycées are destined to take the place of the boarding-schools of former days; for the latter are gradually disappearing or transforming themselves into daily cours (classes), where women absorbed by their social duties, or fortunate enough to be wanted as companions by their husbands, will wisely send their daughters. The day when girls' colleges triumph in France, there will be many more analogies between French and American women than there are now.

There is one establishment which, in spite of all, it will be difficult to make democratic, and that is the once imperial house of the Legion of Honor. I mentioned the Prytanée a while ago; this is also a special school, where the daughters and granddaughters of officers alone have the right of gratuitous admission, to the number of four or five hundred. Napoleon founded it in 1809, when he transferred his military school to the St. Cyr buildings, where in other days, under Mine. de Maintenon's rule, the daughters of poor noblemen were educated. The Emperor wanted to emulate Louis XIV in securing a good education for the daughters of those of his companions in arms who had fallen on the field of honor. He intrusted the reins of government to Mme. Campan, that honored pedagogue who had educated Queen Hortense, Josephine's daughter. The setting is imposing. The Abbey of St. Denis, the burial-place of the kings of France, one of our principal historical monuments, casts its great shadow on these young creatures. No instruction could be more thorough than that given them, nor could there be more rigorous regulations than those to which they are subjected. The house is strictly closed, and opens its doors only to visitors provided with a pass furnished by the Chancellor of the Legion of Honor, who controls it. The boarding-school has been located in immense, damp, vaulted halls that cannot possibly be warmed, and they are, besides, separated by long cloisters; the regulations are more severe than those of any convent, being almost military; the feeling of honor is inculcated in these children as it would be in all soldiers. All taste in dress is stoically repressed. The hideousness of their black costume is carried to exaggeration; their hair is cut short; they never go out. But how proud they are to form a part of that élite. This feeling begins at the superintendent, who wears the great ribbon of the Legion of Honor, and it extends to the professors called "dames de St. Denis," all of them former pupils. Although unmarried, they have the right to be addressed as "madam." This historical and military setting develops most peculiar individualities and characters. A St. Denis pupil is often recognized by her superiority, and not less frequently by her pretensions; but she will never be found commonplace.

It is quite clear that, whether it be for better or for worse, we are gradually approaching an order of things more American than French, in the old sense of the word. As regards children, the prison-like school has opened its doors, boarding lycées seem to be losing favor, and scholars can enjoy all the bodily exercise that tempts schoolboys on the other side of the Atlantic. At the same time, the number of those who finish their course in the "humanities," that splendid name that nothing else can replace, is growing smaller; some are content to follow merely the so-called modern course. The hurried and curtailed education which permits an early entrance into practical life has numerous partizans.

I trust, however, that we may never lose sight of the fact that education does not consist in a more or less vast and varied instruction, documented and secured by a greater or less number of diplomas, but that it is what was so excellently said by a Frenchman of the good old time, Montaigne, "the moral institution of man."

Th. Bentzon.

Notes

(1) For a biographical and critical paper by Will H. Low on Maurice Boutet de Monvel see THE CENTURY for June, 1894. This artist is distinguished not only his masterly portrayal of children, on their humorous side, as in "Nos Enfants," etc., but he has shown himself to be a strong and original portrait-painter, and a faithful and masterly depicter of the charm and pathos of peasant life, in his illustrations for "Xaviére," and in his forthcoming illustrations of the life of Jeanne d'Arc. The next number of THE CENTURY will contain examples of Boutet de Monvel's treatment of the principal scenes in the life of the Maid of Orleans--EDITOR.

(2) And by the weight of all the skeins I wrought

I kept the measure of my loving thought;

Among the broken threads serene it ran

And, interrupted oft, anew began.

(3) head-protectors for infants.

(4) A part of Nivernais, near Burgundy.

(5) Children of the troop, if they belong to military families, are educated to be good non-commissioned officers at the State's expense

(6) La Flèche is a pretty, small town in Maine, with Prytanée

for its prominent feature.

Edited by Terry Heller, Coe College.