| King of Folly Island Contents | Scribner's Text |

LAW LANE.

Sarah Orne Jewett

I.

The thump of a flat-iron signified to an educated passer-by that this was Tuesday morning; yesterday having been fair and the weekly washing-day unhindered by the weather. It was undoubtedly what Mrs. Powder pleased herself by calling a good orthodox week; not one of the disjointed and imperfect sections of time which a rainy Monday forced upon methodical housekeepers. Mrs. Powder was not a woman who could live altogether in the present, and whatever she did was done with a view to having it cleared out of the way of the next enterprise on her list. "I can't bear to see folks do their work as if every piece on 't was a tread-mill," she used to say, briskly. "Life means progriss to me, and I can't dwell by the way no more 'n sparks can fly downwards. 'T ain't the way I'm built, nor none of the Fisher tribe."

The hard white bundles in the shallow splint-basket were disappearing, one by one, and taking their places on the decrepit clothes-horse, well ironed and precisely folded. The July sunshine came in at one side of Mrs. Powder's kitchen, and the cool northwest breeze blew the heat out again from the other side. Mrs. Powder grew uneasy and impatient as she neared the end of her task, and the flat-iron moved more and more vigorously. She kept glancing out through the doorway and along the country road as if she were watching for somebody.

"I shall just have to git ready an' go an' rout her out myself, an' take my chances," she said at last with a resentful look at the clock, as if it were partly to blame for the delay and had ears with which to listen to proper rebuke. The round moon-face had long ago ceased its waxing and waning across the upper part of the old dial, as if it had forgotten its responsibility about the movements of a heavenly body in its pleased concern about housekeeping.

"See here!" said Mrs. Powder, taking a last hot iron from the fire. "You ain't a-keepin' time like you used to; you're gettin' lazy, I must say. Look at this 'ere sun-mark on the floor, that calls it full 'leven o'clock, and you want six minutes to ten. I've got to send word to the clock-man and have your in'ards all took apart; you got me to meetin' more 'n half an hour too late, Sabbath last."

To which the moon-face did not change its beaming expression; very likely, being a moon, it was not willing to mind the ways of the sun.

"Lord, what an old thing you be!" said Mrs. Powder, turning away with a chuckle. "I don't wonder your sense kind of fails you!" And the clock clucked at her by way of answer, though presently it was going to strike ten at any rate.

The hot iron was now put down hurriedly, and the half-ironed night-cap was left in a queer position on the ironing-board. A small figure had appeared in the road and was coming toward the house with a fleet, barefooted run which required speedy action. "Here you, Joel Smith!" shouted the old woman. "Jo--el!" But the saucy lad only doubled his pace and pretended not to see or hear her. Mrs. Powder could play at that game, too, and did not call again, but quietly went back to her ironing and tried as hard as she could to be provoked. Presently the boy came panting up the slope of green turf which led from the road to the kitchen doorstep.

"I didn't know but you spoke as I ran by," he remarked, in an amiable tone. Mrs. Powder took no heed of him whatever.

"I ain't in no hurry; I kind o' got running," he explained, a moment later; and then, as his hostess stepped toward the stove, he caught up the frilled night-cap and tied it on in a twinkling. When Mrs. Powder turned again, the sight of him was too much for her gravity.

"Them frills is real becoming to ye," she announced, shaking with laughter. "I declare for 't if you don't favor your gran'ma Dodge's looks. I should like to have yer folks see ye. There, take it off now; I'm most through my ironin' and I want to clear it out o' the way."

Joel was perfectly docile and laid the night-cap within reach. He had a temptation to twitch it back by the end of one string, but he refrained. "Want me to go drive your old brown hen-turkey out o' the wet grass, Mis' Powder? She's tolling her chicks off down to'a'ds the swamp," he offered.

"She's raised up families enough to know how by this time," said Mrs. Powder, "an' the swamp's dry as a bone."

"I'll split ye up a mess o' kindlin'-wood whilst I'm here, jest as soon 's not," said Joel, in a still more pleasant tone, after a long and anxious pause.

"There, I'll get ye your doughnuts, pretty quick. They ain't so fresh as they was Saturday. I s'pose that's what you're driving at." The good soul shook with laughter. Joel answered as well for her amusement as the most famous of comic actors; there was something in his appealing eyes, his thin cheeks and monstrous freckles, and his long locks of sandy hair, which was very funny to Mrs. Powder. She was always interested, too, in fruitless attempts to satisfy his appetite. He listened now, for the twentieth time, to her opinion that the bottomless pit alone could be compared to the recesses of his being.

"I should like to be able to say that I had filled ye up jest once!" she ended her remarks, as she brought a tin pan full of doughnuts from her pantry.

"Heard the news?" asked small Joel, as he viewed the provisions with glistening eyes. He bore likeness to a little hungry woodchuck, or muskrat, as he went to work before the tin pan.

"What news?" Mrs. Powder asked, suspiciously. "I ain't seen nobody this day."

"Barnet's folks has got their case in court."

"They ain't!" and while a solemn silence fell upon the kitchen, the belated old clock whirred and rumbled and struck ten with persistent effort. Mrs. Powder looked round at it impatiently; the moon-face confronted her with the same placid smile.

"Twelve o'clock's the time you git your dinner, ain't it, Mis' Powder?" the boy inquired, as if he had repeated his news like a parrot and had no further interest in its meaning.

"I don't plot for to get me no reg'lar dinner this day," was the unexpected reply. "You can eat a couple or three o' them nuts and step along, for all I care. An' I want you to go up Lyddy Bangs's lane and carry her word that I'm goin' out to pick me some blueberries. They'll be ripened up elegant, and I've got a longin' for 'em. Tell her I say 't is our day -- she'll know; we've be'n after 'arly blueberries together this forty years, and Lyddy knows where to meet with me; there by them split rocks."

The ironing was finished a few minutes afterward, and the board was taken to its place in the shed. When Mrs. Powder returned, Joel had stealthily departed; the tin pan was turned upside down on the seat of the kitchen chair. "Good land!" said the astonished woman, "I believe he'll bu'st himself to everlastin' bliss one o' these days. Them doughnuts would have lasted me till Thursday, certain."

"Gimme suthin' to eat, Mis' Powder?"

whined Joel at the window, with his plaintive countenance lifted

just above the sill. But he set forth immediately down the road,

with bulging pockets and the speed of

a light-horseman.

II.

Half an hour later the little gray farmhouse was shut and locked, and its mistress was crossing the next pasture with a surprisingly quick step for a person of her age and weight. An old cat was trotting after her, with tail high in the air, but it was plain to see that she still looked for danger, having just come down from the woodpile, where she had retreated on Joel's first approach. She kept as close to Mrs. Powder as was consistent with short excursions after crickets or young, unwary sparrows, and opened her wide green eyes fearfully on the lookout for that evil monster, the boy.

There were two pastures to cross, and Mrs. Powder was very much heated by the noonday sun and entirely out of breath when she approached the familiar rendezvous and caught sight of her friend's cape-bonnet.

"Ain't there no justice left?" was her indignant salutation. "I s'pose you've heard that Crosby's folks have lost their case? Poor Mis' Crosby! 't will kill her, I'm sure. I've be'n calculatin' to go berryin' all the forenoon, but I couldn't git word to you till Joel came tootin' by. I thought likely you'd expect notice when you see what a good day 't was."

"I did," replied Lyddy Bangs, in a tone much more serious than her companion's. She was a thin, despairing little body, with an anxious face and a general look of disappointment and poverty, though really the more prosperous person of the two. "Joel told me you said 't was our day," she added. "I'm wore out tryin' to satisfy that boy; he's always beggin' for somethin' to eat every time he comes nigh the house. I should think they'd see to him to home; not let him batten on the neighbors so."

"You ain't been feedin' of him, too?" laughed Mrs. Powder. "Well, I declare, I don't see whar he puts it!" and she fanned herself with her apron. "I always forget what a sightly spot this is."

"Here's your pussy-cat, ain't she?" asked Lyddy Bangs, needlessly, as they sat looking off over the valley. Behind them the hills rose one above another, with their bare upland clearings and great stretches of pine and beech forest. Beyond the wide valley was another range of hills, green and pleasant in the clear mid-day light. Some higher mountains loomed, sterile and stony, to northward. They were on the women's right as they sat looking westward.

"It does seem as if folks might keep the peace when the Lord's give 'em so pooty a spot to live in," said Lyddy Bangs, regretfully. "There ain't no better farms than Barnet's and Crosby's folks have got neither, but 'stead o' neighboring they must pick their mean fusses and fight from generation to generation. My gran'ma'am used to say 't was just so with 'em when she was a girl -- and she was one of the first settlers up this way. She al'ays would have it that Barnet's folks was the most to blame, but there's plenty sides with 'em, as you know."

"There, 't is all mixed up, so 't is -- a real tangle," answered Mrs. Powder. "I've been o' both minds -- I must say I used to hold for the Crosbys in the old folks' time, but I've come round to see they ain't perfect. There! I'm b'ilin' over with somethin' I've got to tell somebody. I've kep' it close long 's I can."

"Let's get right to pickin', then," said Lyddy Bangs, "or we sha'n't budge from here the whole livin' afternoon," and the small thin figure and the tall stout one moved off together toward their well-known harvest-fields. They were presently settled down within good hearing distance, and yet the discussion was not begun. The cat curled herself for a nap on the smooth top of a rock.

"There, I have to eat a while first, like a young-one," said Mrs. Powder. "I always tell 'em that blueberries is only fit to eat right off of the twigs. You want 'em full o' sun; let 'em git cold and they're only fit to cook -- not but what I eat 'em any ways I can git 'em. Ain't they nice an' spicy? Law, my poor knees is so stiff! I begin to be afraid, nowadays, every year o' berryin' may be my last. I don' know why 't should be that my knees serves me so. I ain't rheumaticky, nor none o' my folks was; we go off with other complaints."

"The mukis membrane o' the knees gits dried up," explained Lyddy Bangs, "an' the j'ints is all powder-posted. So I've be'n told, anyways."

"Then they was ignorant," retorted her companion, sharply. "I know by the feelin's I have" -- and the two friends picked industriously and discussed the vexed points of medicine no more.

"I can't force them Barnets and Crosbys out o' my mind," suggested Miss Bangs after a while, being eager to receive the proffered confidence which might be forgotten. "Think of 'em, without no other door-neighbors, fightin' for three ginerations over the bounds of a lane wall. What if 't was two foot one way or two foot t'other, let 'em agree."

"But that's just what they couldn't," said Mrs. Powder. "You know yourself you might be willin' to give away a piece o' land, but when somebody said 't wa'n't yours, 't was theirs, 't would take more Christian grace 'n I've got to let 'em see I thought they was right. All the old Crosbys ever wanted, first, was for the Barnets to say two foot of the lane was theirs by rights, and then they was willin' to turn it into the lane and to give that two foot more o' the wedth than Barnets did -- they wa'n't haggling for no pay; 't was for rights. But Barnet's folks said" --

"Now, don't you go an' git all flustered up a-tellin' that over, Harri't Powder," said the lesser woman. "There ain't be'n no words spoke so often as them along this sidelin' hill, not even the Ten Commandments. The only sense there's be'n about it is, they've let each other alone altogether, and ain't spoke at all for six months to a time. I can't help hoping that the war'll die out with the old breed and they'll come to some sort of peace. Mis' Barnet was a Sands, and they're toppin' sort o' folks and she's got fight in her. I think she's more to blame than Barnet, a good sight; but Mis' Crosby's a downright peace-making little creatur', and would have ended it long ago if she'd be'n able."

"Barnet's stubborn, too, let me tell you!" and Mrs. Powder's voice was full of anger. "'T will never die out in his day, and he'll spend every cent lawing, as the old folks did afore him. The lawyers must laugh at him well, 'mongst themselves. One an' another o' the best on 'em has counseled them to leave it out to referees, and tried to show 'em they was fools. My man talked with [the] judge himself about it, once, after he'd been settin' on a jury and they was comin' away from court. They couldn't agree; they never could! All the spare money o' both farms has gone to pay the lawyers and carry on one fight after another. Now folks don't know it, but Crosby's farm is all mortgaged; they've spent even what Mis' Crosby had from her folks. An' there's worse behind -- there's worse behind," insisted the speaker, stoutly. "I went up there this spring, as you know, when Mis' Crosby was at death's door with lung-fever. I went through everything fetchin' of her round, and was there five weeks, till she got about. `I feel to'a'ds you as an own sister,' says Abby Crosby to me. `I'm a neighboring woman at heart,' says she; `and just you think of it, that my man had to leave me alone, sick as I was, while he went for you and the doctor, not riskin' to ask Barnet's folks to send for help. I like to live pleasant,' says she to me, and bu'st right out a-cryin'. I knew then how she'd felt things all these years. -- How are they ever goin' to pay more court bills and all them piles o' damages, if the farm's mortgaged so heavy?" she resumed. "Crosby's farm ain't worth a good two thirds of Barnet's. They've both neglected their lands. How many you got so fur, Lyddy?"

Lyddy proudly displayed her gains of blueberries; the pail was filling very fast, and the friends were at their usual game of rivalry. Mrs. Powder had been the faster picker in years past, and she now doubled her diligence.

"Ain't the sweet-fern thick an' scented as ever you see?" she said. "Gimme pasture-lands rather 'n the best gardins that grows. If I can have a sweet-brier bush and sweet-fern patch and some clumps o' bayberry, you can take all the gardin blooms. Look how folks toils with witch-grass and pusley and gets a starved lot o' poor sprigs, slug-eat, and all dyin' together in their front yards, when they might get better comfort in the first pasture along the road. I guess there's somethin' wild, that's never got tutored out o' me. I must ha' be'n made o' somethin' counter to town dust. I never could see why folks wanted to go off an' live out o' sight o' the mountings, an' have everything on a level."

"You said there was worse to tell behind," suggested Lyddy Bangs, as if it were only common politeness to show an appreciation of the friendly offering.

"I have it in mind to get round to that in proper course," responded Mrs. Powder, a trifle offended by the mild pertinacity. "I settled it in my mind that I was goin' to tell you somethin' for a kind of a treat the day we come out blueberryin'. There!" -- and Mrs. Powder rose with difficulty from her knees, and retreated pompously to the shade of a hemlock-tree which grew over a shelving rock near by.

Lyddy Bangs could not resist picking a little longer in an unusually fruitful spot; then she hastened to seat herself by her friend. It was no common occasion.

Mrs. Powder was very warm; and further evaded and postponed telling the secret by wishing that she were as light on foot as her companion, and deploring her increasing weight. Then she demanded a second sight of the blueberries, which were compared and decided upon as to quality and quantity. Then the cat, which had been left at some distance on her rock, came trotting toward her mistress in a disturbed way, and after a minute of security in a comfortable lap darted away again in a strange, excited manner.

"She's goin' to have a fit, I do believe!" exclaimed Lyddy Bangs, quite disheartened, for the cat was Mrs. Powder's darling and she might leave everything to go in search of her.

"She may have seen a snake or something. She often gets scared and runs home when we're out a-trarvelin'," said the cat's owner, complacently, and Lyddy's spirits rose again.

"I suppose you never suspected that Ezra Barnet and Ruth Crosby cared the least thing about one another?" inquired the keeper of the secret a moment later, and the listener turned toward Mrs. Powder with a startled face.

"Now, Harri't Powder, for mercy's sakes alive!" was all that she could say; but Mrs. Powder was satisfied, and confirmed the amazing news by a most emphatic nod.

"My lawful sakes! what be they goin' to do about it?" inquired Lyddy Bangs, flushing with excitement. "A Barnet an' a Crosby fall in love! Don't you rec'lect how the old ones was al'ays fightin' and callin' names when we was all to school together? Times is changed, certain."

"Now, say you hope to die if ever you'll tell a word I say," pursued Mrs. Powder. "If I was to be taken away to-morrow, you'd be all the one that would know it except Mis' Crosby and Ezra and Ruth themselves. 'T was nothin' but her bein' nigh to death that urged her to tell me the state o' things. I s'pose she thought I might favor 'em in time to come. Abby Crosby she says to me, `Mis' Powder, my poor girl may need your motherin' care.' An' I says, `Mis' Crosby, she shall have it;' and then she had a spasm o' pain, and we harped no more that day as I remember."

"How come it about? I shouldn't have told anybody that asked me that a Barnet and a Crosby ever 'changed the time o' day, much less kep' company," protested the listener.

"Kep' company! pore young creatur's!" said Mrs. Powder. "They've hid 'em away in the swamps an' hollers, and in the edge o' the growth, at nightfall, for the sake o' gittin' a word; an' they've stole out, shiverin', into that plaguy lane o' winter nights. I tell ye I've heard hifalutin' folks say that love would still be lord of all, but I never was 'strained to believe it till I see what that boy and girl was willin' to undergo. All the hate of all their folks is turned to love in them, and I couldn't help a-watchin' of 'em. An' I ventured to send Ruth over to my house after my alpaccy aprin, and then I made an arrant out to the spring-brook to see if there was any cresses started -- which I knew well enough there wasn't -- and I spoke right out bold to Ezra, that was at work on a piece of ditching over on his land. `Ezra,' says I, `if you git time, just run over to the edge o' my pasture and pick me a handful o' balm o' Gilead buds. I want to put 'em in half a pint o' new rum for Mis' Crosby, and there ain't a soul to send.' I knew he'd just meet her coming back, if I could time it right gittin' of Ruth started. He looked at me kind of curi's, and pretty quick I see him leggin' it over the fields with an axe and a couple o' ends o' board, like he'd got to mend a fence. I had to keep her dinner warm for her till ha'-past one o'clock. I don't know what he mentioned to his folks, but Ruth she come an' kissed me hearty when she first come inside the door. 'Tis harder for Ezra; he ain't got nobody to speak to, and Ruth's got her mother if she is a Mis' Much-afraid."

"I don't know 's we can blame Crosby for not wantin' to give his girl to the Barnets, after they've got away all his substance, his means, an' his cattle, like 't was in the Book o' Job," urged Lyddy Bangs. "Seems as if they might call it square an' marry the young folks off, but they won't nohow; 't will only fan the flame." Lyddy Bangs was a sentimental person; neighbor Powder had chosen wisely in gaining a new friend to the cause of Ezra Barnet's apparently hopeless affection. Unknown to herself, however, she had been putting the lover's secret to great risk of untimely betrayal.

The weather was most beautiful that afternoon; there was an almost intoxicating freshness and delight among the sweet odors of the hillside pasture, and the two elderly women were serene at heart and felt like girls again as they talked together. They remembered many an afternoon like this; they grew more and more confiding as they reviewed the past and their life-long friendship. A stranger might have gathered only the most rural and prosaic statements, and a tedious succession of questions, from what Mrs. Powder and Lyddy Bangs had to say to each other, but the old stories of true love and faithful companionship were again simply rehearsed. Those who are only excited by more complicated histories too often forget that there are no new plots to the comedies and tragedies of life. They are played sometimes by country people in homespun, sometimes by townsfolk in velvet and lace. Love and prosperity, death and loss and misfortune -- the stories weave themselves over and over again, never mind whether the ploughman or the wit of the clubs plays the part of hero.

The two homely figures sat still so long that they seemed to become permanent points in the landscape, and the small birds, and even a wary chipmunk, went their ways unmindful of Mrs. Powder and Lyddy Bangs. The old hemlock-tree, under which they sat discoursing, towered high above the young pine-growth which clustered thick behind them on the hillside. In the middle of a comfortable reflection upon the Barnet grandfather's foolishness or craftiness, Mrs. Powder gave sudden utterance to the belief that some creature up in the tree was dropping pieces of bark and cones all over her.

"A squirrel, most like," said Lyddy Bangs, looking up into the dense branches. "The tree is a-scatterin' down, ain't it? As you was sayin', Grandsir Barnet must have knowed well enough what he was about" --

"Oh, gorry! oh, git out! ow--o--w!" suddenly wailed a voice overhead, and a desperate scramble and rustling startled the good women half out of their wits. "Ow, Mis' Powder!" shrieked a familiar voice, while both hearts thumped fast, and Joel came, half falling, half climbing, down out of the tree. He bawled, and beat his head with his hands, and at last rolled inagony among the bayberry and lamb-kill. "Look out for 'em!" he shouted. "Oh, gorry! I thought 't was only an old last-year's hornet's nest -- they'll sting you, too!"

Mrs. Powder untied her apron and laid about her with sure aim. Only two hornets were to be seen; but after these were beaten to the earth, and she stopped to regain her breath, Joel hardly dared to lift his head or to look about him.

"What was you up there for, anyhow?" asked Lyddy Bangs, with severe suspicion. "Harking to us, I'll be bound!" But Mrs. Powder, who knew Joel's disposition best, elbowed her friend into silence and began to inquire about the condition of his wounds. There was a deep-seated hatred between Joel and Miss Bangs.

"Oh, dear! they've bit me all over," groaned the boy. "Ain't you got somethin' you can rub on, Mis' Powder?" -- and the rural remedy of fresh earth was suggested.

"'Tis too dry here," said the adviser. "Just you step down to that ma'shy spot there by the brook, dear, and daub you with the wet mud real good, and 't will ease you right away." Mrs. Powder's voice sounded compassionate, but her spirit and temper of mind gave promise of future retribution.

"I'll teach him to follow us out eavesdropping, this fashion!" said Lyddy Bangs, when the boy had departed, weeping. "I'm more 'n gratified that the hornets got hold of him! I hope 't will serve him for a lesson."

"Don't you r'ile him up one mite, now," pleaded Mrs. Powder, while her eyes bore witness of hardly controlled anger. "He's the worst tattle-tale I ever see, and we've put ourselves into a trap. If he tells his mother she'll spread it all over town. But I should no more thought o' his bein' up in that tree than o' his bein' the sarpent in the garden o' Eden. You leave Joel to me, and be mild with him 's you can."

The culprit approached, still lamenting. His ear and cheek were hugely swollen already, so that one eye was nearly closed. The blueberry expedition was relinquished, and with heavy sighs of dissatisfaction Lyddy Bangs took up the two half-filled pails, while Mrs. Powder kindly seized Joel by his small, thin hand, and the little group moved homeward across the pasture.

"Where's your hat?" asked Lyddy, stopping short, after they had walked a little distance.

"Hanging on a limb up by the wop's

nest," answered Joel. "Oh, git me home, Mis' Powder!"

III.

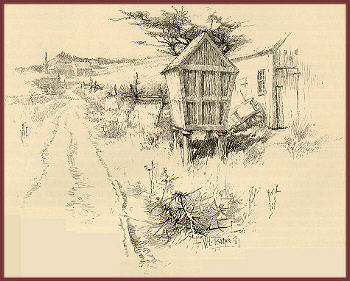

No one would suspect, from the look of the lane itself, that it had always been such a provoker of wrath, and even a famous battle-ground. While petty wars had raged between the men and women of the old farms, walnut-trees had grown high in air, and apple-trees had leaned their heavy branches on the stone walls and, year after year, decked themselves in pink-and-white blossoms to arch this unlucky by-way for a triumphal procession of peace that never came. Birds built their nests in the boughs and pecked the ripe blackberries; green brakes and wild roses and tall barberry-bushes flourished in their season on either side the wheel-ruts. It was a remarkably pleasant country lane, where children might play and lovers might linger. No one would imagine that this lane had its lawsuits and damages, its annual crop of briefs, and succession of surveyors and quarrelsome partisans; or that in every generation of owners each man must be either plaintiff or defendant.

The surroundings looked permanent enough. No one would suspect that a certain piece of wall had been more than once thrown down by night and built again, angrily, by day; or that a well-timbered corn-house had been the cause of much litigation, and even now looked, when you came to know its story, as if it stood on its long, straight legs, like an ungainly, top-heavy beast, all ready to stalk away when its position became too dangerous. The Barnets had built it beyond their boundary; it had been moved two or three times, backward and forward.

The Barnet house and land stood between the Crosby farm and the high-road; the Crosbys had never been able to reach the highway without passing their enemies under full fire of ugly looks or taunting voices. The intricacies of legal complications in the matter of right of way would be impossible to explain. They had never been very clear to any impartial investigator. Barnets and Crosbys had gone to their graves with bitter hatred and sullen desire for revenge in their hearts. Perhaps this one great interest, outside the simple matters of food and clothing and farmers' work, had taken the place to them of drama and literature and art. One could not help thinking, as he looked at the decrepit fences and mossy, warped roofs and buckling walls, to how much better use so much money might have been put. The costs of court and the lawyers' fees had taken everything, and men had drudged, in heat and frost, and women had pinched and slaved to pay the lane's bills. Both the Barnet and Crosby of the present time stood well enough in the opinion of other neighbors. They were hard-fisted, honest men; the fight was inherited to begin with, and they were stubborn enough to hold fast to the fight. Law Lane was as well known as the county roads in half a dozen towns. Perhaps its irreconcilable owners felt a thrill of enmity that had come straight down from Scottish border-frays, as they glanced along its crooked length. Who could believe that the son and daughter of the warring households, instead of being ready to lift the torch in their turn, had weakly and misguidedly fallen in love with each other?

Nobody liked Mrs. Barnet. She was a cross-grained, suspicious soul, who was a tyrant and terror of discomfort in her own household whenever the course of events ran counter to her preference. Her son Ezra was a complete contrast to her in disposition, and to his narrow-minded, prejudiced father as well. The elder Ezra was capable of better things, however, and might have been reared to friendliness and justice, if the Crosby of his youthful day had not been specially aggravating and the annals of Law Lane at their darkest page. If there had been another boy to match young Ezra, on the Crosby farm, the two might easily have fostered their natural boyish rivalries until something worse came into being; but when one's enemy is only a sweet-faced little girl, it is very hard to impute to her all manner of discredit and serpent-like power of evil. At least, so Ezra Barnet the younger felt in his inmost heart; and though he minded his mother for the sake of peace, and played his solitary games and built his unapplauded dams and woodchuck-traps on his own side of the fences, he always saw Ruth Crosby as she came and went, and liked her better and better as years went by. When the tide of love rose higher than the young people's steady heads, they soon laid fast hold of freedom. With all their perplexities, life was by no means at its worst, and rural diplomacy must bend all its energies to hinder these unexpected lovers.

Ezra Barnet had never so much as entered the Crosby house; the families were severed beyond the reuniting power of even a funeral. Ezra could only try to imagine the room to which his Ruth had returned one summer evening after he had left her, reluctantly, because the time drew near for his father's return from the village. His mother had been in a peculiarly bad temper all day, and he had been glad to escape from her unwelcome insistence that he should marry any one of two or three capable girls, and so furnish some help in the housekeeping. Ezra had often heard this suggestion of his duty, and, tired and provoked at last, he had stolen out to the garden and wandered beyond it to the brook and out to the fields. Somewhere, somehow, he had met Ruth, and the lovers bewailed their trials with unusual sorrow and impatience. It seemed very hard to wait. Young Barnet was ready to persuade the tearful girl that they must go away together and establish a peaceful home of their own. He was heartily ashamed because the last verdict was in his father's favor, and Ruth forebore to wound him with any glimpse of the straits to which her own father had been reduced. She was too dutiful to leave the pinched household, where her help was needed more than ever; she persuaded her lover that they were sure to be happy at last -- indeed, were not they happy now? How much worse it would be if they could not safely seize so many opportunities, brief though they were, of being together! If the fight had been less absorbing and the animosity less bitter, they might have been suspected long ago.

So Ruth and Ezra parted, with uncounted kisses, and Ezra went back to the dingy-walled kitchen, where his mother sat alone. It was hardly past twilight out of doors, but Mrs. Barnet had lighted a kerosene-lamp, and sat near the small open window mending a hot-looking old coat. She looked so needlessly uncomfortable and surly that her son was filled with pity, as he stood watching her, there among the moths and beetles that buffeted the lamp-chimney.

"Why don't you put down your sewing and come out a little ways up the road, mother, and get cooled off?" he asked, pleasantly; but she only twitched herself in her chair and snapped off another needleful of linen thread.

"I can't spare no time to go gallivantin', like some folks," she answered. "I always have had to work, and I always shall. I see that Crosby girl mincin' by an hour ago, as if she'd be'n off all the afternoon. Folks that think she's so amiable about saving her mother's strength would be surprised at the way she dawdles round, I guess" -- and Mrs. Barnet crushed an offending beetle with her brass thimble in a fashion that disgusted Ezra. Somehow, his mother had a vague instinct that he did not like to hear sharp words about Ruth Crosby. Yet he rarely had been betrayed into an ill-judged defense. He had left Ruth only a minute ago; he knew exactly what she had been doing all day, and from what kind errand she had been returning; the blood rushed quickly to his face, and he rose from his seat by the table and went out to the kitchen doorstep. The air was cool and sweet, and a sleepy bird chirped once or twice from an elm-bough overhead. The moon was near its rising, and he could see the great shapes of the mountains that lay to the eastward. He forgot his mother, and began to think about Ruth again; he wondered if she were not thinking of him, and meant to ask her if she remembered an especial feeling of nearness just at this hour. Ezra turned to look at the clocks to mark the exact time.

"Yes," said Mrs. Barnet, as she saw him try to discover the hour, "'tis time that father was to home. I s'pose, bein' mail-night, everybody was out to the post-office to hear the news, and most like he's bawlin' himself hoarse about fall 'lections or something. He ain't got done braggin' about our gittin' the case, neither. There's always some new one that wants to git the p'ints right from headquarters. I didn't see Crosby go by, did you?"

"He'd have had to foot it by the path 'cross-lots," replied Ezra, gravely, from the doorstep. "He's sold his hoss."

"He ain't!" exclaimed Mrs. Barnet, with a chuckle. "I s'pose they're proddin' him for the money up to court. Guess he won't try to fight us again for one while."

Ezra said nothing; he could not bear this sort of thing much longer. "I won't be kept like a toad under a harrow," he muttered to himself. "I think it seems kind of hard," he ventured to say aloud. "Now he's got to hire when fall work comes on, and" --

The hard-hearted woman within had long been trying to provoke her peaceable son into an argument, and now the occasion had come. Ezra restrained himself from speech with a desperate effort, and stopped his ears to the sound of his mother's accusing voice. In the middle of her harangue a wagon was driven into the yard, and his father left it quickly and came toward the door.

"Come in here, you lout!" he shouted, angrily. "I want to look at you! I want to see what such a mean-spirited sneak has got to say for himself." Then changing his voice to a whine, he begged Ezra, who had caught him from falling as he stumbled over the step, "Come in, boy, an' tell me 't ain't true. I guess they was only thornin' of me up; you ain't took a shine to that Crosby miss, now, have you?"

"No son of mine -- no son of mine!" burst out the mother, who had been startled by the sudden entrance of the news-bringer. Her volubility was promptly set free, and Ezra looked from his father's face to his mother's.

"Father," said he, turning away from the scold, who was nearly inarticulate in her excess of rage -- "father, I'd rather talk to you, if you want to hear what I've got to say. Mother's got no reason in her."

"Ezry," said the elder man, "I see how 'tis. Let your ma'am talk all she will. I'm broke with shame of ye!" -- his voice choked weakly in his throat. "Either you tell me 'tis all nonsense, or you go out o' that door and shut it after you for good. An' ye're all the boy I've got."

The woman had stopped at last, mastered by the terror of the moment. Her husband's face was gray with passion; her son's cheeks were flushed and his eyes were full of tears. Mrs. Barnet's tongue for once had lost its cunning.

The two men looked at each other as long as they could; the younger man's eyes fell first. "I wish you wouldn't be hasty," he said; "to-morrow" --

"You've heard," was the only answer; and in a moment more Ezra Barnet reached to the table and took his old straw hat which lay there.

"Good-by, father!" he said, steadily. "I think you're wrong, sir; but I never meant to carry on that old fight and live like the heathen." And then, young and strong and angry, he left the kitchen.

"He might have took some notice o' me, if he's goin' for good," said the mother spitefully; but her son did not hear this taunt, and the father only tottered where he stood. The moths struck against his face as if it were a piece of wood; he sank feebly into a chair, muttering, and trying to fortify himself in his spent anger.

Ezra went out, dazed and giddy. But he found the young horse wandering about the yard, eager for his supper and fretful at the strange delay. He unharnessed the creature and backed the wagon under the shed; then he turned and looked at the house -- should he go in? No! The fighting instinct, which had kept firm grasp on father and grandfather, took possession of Ezra now. He crossed the yard and went out at the gate, and down the lane's end to the main road. The father and mother listened to his footsteps, and the man gave a heavy groan.

"Let him go -- let him go! 't will

teach him a lesson!" said Mrs. Barnet, with something of her

usual spirit. She could not say more, though she tried her best;

the occasion was far too great.

How many times that summer Mrs. Powder attempted to wreak vengeance upon Joel, the tattle-tale; into what depths of intermittent remorse the mischief-making boy was resolutely plunged, who shall describe? No more luncheons of generous provision; no more jovial skirmishing at the kitchen windows, or liberal payment for easy errands. Whenever Mrs. Powder saw Lyddy Bangs, or any other intimate and sympathetic friend, she bewailed her careless confidences under the hemlock-tree and detailed her anxious attentions to the hornet-stung eavesdropper.

"I went right home," she would say, sorrowfully; "I filled him plumb-full with as good a supper as I could gather up, and I took all the fire out o' them hornit-stings with the best o' remedies. `Joel, dear,' says I, `you won't lose by it if you keep your mouth shut about them words I spoke to Lyddy Bangs,' and he was that pious I might ha' known he meant mischief. They ain't boys nor men, they're divils, when they come to that size, and so you mark my words! But his mother never could keep nothing to herself, and I knew it from past sorrers; and I never slept a wink that night -- sure 's you live -- till the roosters crowed for day."

"Perhaps 't won't do nothin' but good!" Lyddy Bangs would say, consolingly. "Perhaps the young folks 'll git each other a sight the sooner. They'd had to kep' it to theirselves till they was gray-headed, 'less somebody let the cat out o' the bag."

"Don't you rec'lect how my cat acted

that day!" exclaimed Mrs. Powder excitedly. "How she was good as

took with a fit! She knowed well enough what was brewin'; I only

wish we'd had half of her sense."

IV.

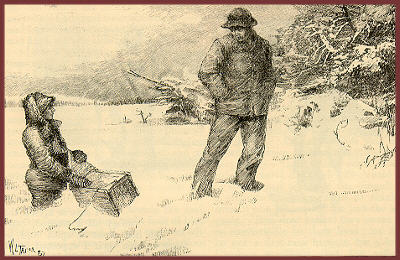

The day before Christmas all the long

valley was white with deep, new-fallen snow. The road which led

up from the neighboring village and the railroad station

stretched along the western slope -- a mere trail, untrodden and

unbroken. The storm had just ceased; the high mountain-peaks

were clear and keen and rose-tinted with the waning light; the

hills were no longer green with their covering of pines and

maples and beeches, but gray with bare branches, and a cold,

dense color, almost black, where the evergreens grew thickest.

On the other side of the valley the farmsteads were mapped out

as if in etching or pen-drawing; the far-away orchards were

drawn with a curious exactness and regularity, the crooked

boughs of the apple-trees and the longer lines of the walnuts

and ashes and elms came out against the snow with clear beauty.

The fences and walls were buried in snow; the farm-houses and

barns were petty shapes in their right-angled unlikeness to

natural growths. You were half amused, half shocked, as the

thought came to you of indifferent creatures called men and

women, who busied themselves within those narrow walls, under so

vast a sky, and fancied the whole importance of the universe was

belittled by that of their few pent acres. What a limitless

world lay outside those plaything-farms, yet what beginnings of

immortal things the small gray houses had known!

The day before Christmas! -- a festival which seemed in

that neighborhood to be of modern origin.

The observance of it was hardly popular yet among the elder

people, but Christmas had been appropriated, nevertheless, as if

everybody had felt the lack of it. New Year's Day never was

sufficient for New England, even in its least mirthful decades.

For those persons who took true joy in life, something deeper

was needed than the spread-eagle self-congratulations of the Fourth of July, or the family reunions of Thanksgiving Day. There were no bells

ringing which the country-folks in Law Lane might listen for on

Christmas Eve; but something more than the joy that is felt in

the poorest dwelling when a little child, with all its

possibilities, is born; something happier still came through

that snowy valley with the thought of a Christmas-Child who "was

the bringer-in and founder of the reign

of the higher life." This was the greater Thanksgiving Day

when the whole ofChristendom is called

to praise and pray and hear the good-tidings, and every heart

catches something of the joyful inspirations of good-will to men.

Ezra Barnet sat on a fallen tree from which he had brushed the powdery snow. It was hard work wading through the drifts, and he had made good headway up the long hill before he stopped to rest. Across the valley in the fading daylight he saw the two farms, and could even trace the course of Law Lane itself, marked by the well-known trees. How small his own great nut-tree looked at this distance! The two houses, with their larger and smaller out-buildings and snow-topped woodpiles, looked as if they had crept near together for protection and companionship. There were no other houses within a wide space. Ezra knew how remote the homes really were from each other, judged by any existing sympathy and interest. He thought of his bare, unnourished boyhood with something like resentment; then he remembered how small had been his parents' experience, what poor ambition had been fostered in them by their lives; even his mother's impatience with the efforts he had made to bring a little more comfort and pleasantness to the old farm-house was thought of with pity for her innate lack of pleasure in pleasant things. Ezra himself was made up of inadequacies, being born and bred of the Barnets. He was at work on the railroad now, with small pay; but he had always known that there could be something better than the life in their farmhouse, while his mother did not. A different feeling came over him as he thought whom the other farmhouse sheltered; he had looked for that first, to see if it were standing safe. Ruth's last letter had come only the day before. This Christmas holiday was to be a surprise to her. He wondered whether Ruth's father would let him in.

Never mind! he could sleep in the barn among the hay; and Ezra dropped into the snow again from the old tree-trunk and went his way. There was a small house just past a bend in the road, and he quickened his steps toward it. Alas! there was no smoke in Mrs. Powder's chimney. She was away on one of her visiting tours; nursing some sick person, perhaps. She would have housed him for the night most gladly; now he must take his chances in Law Lane.

The darkness was already beginning to fall; there was a curious brownness in the air, like summer twilight; the cold air became sharper, and the young man shivered a little as he walked. He could not follow the left-hand road, where it led among hospitable neighbors, but turned bravely off toward his old home -- a long, lonely walk at any time of the year, among woods and thickets all well known to him, and as familiar as they were to the wild creatures that haunted them. Yet Ezra Barnet did not find it easy to whistle as he went along.

Suddenly, from behind a scrub-oak that was heavily laden with dead leaves and snow, leaped a small figure, and Ezra was for the moment much startled. The boy carried a rabbit-trap with unusual care, and placed it on the snow-drift before which he stood waist-deep already. "Gorry, Ezry! you most scared me to pieces!" said Joel, in a perfectly calm tone. "Wish you Merry Christmas! Folks'll be lookin' for you; they didn't s'pose you'd git home before to-morrow, though."

"Looking for me?" repeated the young man, with surprise. "I didn't send no word" --

"Ain't you heard nothin' 'bout your ma'am's being took up for dead?"

"No, I ain't; and you ain't foolin' me with your stories, Joel Smith? You needn't play off any of your mischief onto me."

"What you gittin' mad with me about?" inquired Joel, with a plaintive tone in his voice. "She got a fall out in the barn this mornin', an' it liked to killed her. Most folks ain't heard nothin' 'bout it 'cause its been snowin' so. They come for Mis' Powder and she called out to our folks, as they brought her round by the way of Asa Packer's store to git some opodildack or somethin'."

Ezra asked no more questions, but

strode past the boy, who looked after him a moment, and then

lifted the heavy box-trap and started homeward. The imprisoned

rabbit had been snowed up since the day before at least, and

Joel felt humane anxieties, else he would have followed Ezra at

a proper distance and learned something of his reception.

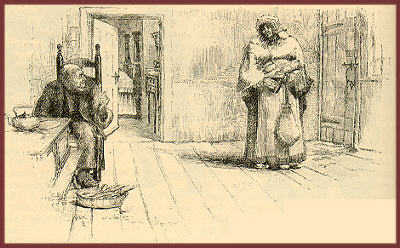

Mrs. Powder was reigning triumphant in the Barnet house, being nurse, housekeeper, and spiritual adviser all in one. She had been longing for an excuse to spend at least half a day under that cheerless roof for many months, but occasion had not offered. She found the responsibility of the parted lovers weighing more and more heavily on her mind, and had set her strong will at work to find some way of reuniting them, and even to restore a long-banished peace to the farms. She would not like to confess that a mild satisfaction caused her heart to feel warm and buoyant when an urgent summons had come at last; but such was the simple truth. A man who had been felling trees on the farm brought the news, melancholy to hear under other circumstances, that Mrs. Barnet had been hunting eggs in a stray nest in the hay-mow, and had slipped to the floor and been taken up insensible. Bones were undoubtedly broken; she was a heavy woman, and had hardly recovered her senses. The doctor must be found as soon as possible. Mrs. Powder hastily put her house to rights, and, with a good round bundle of what she called her needments, set forth on the welcome enterprise. On the way she could hardly keep herself from undue cheerfulness, and if ever there was likely to be a reassuring presence in a sick-room it was Harriet Powder's that December day.

She entered the gloomy kitchen looking like a two-footed snow-drift, her big round shoulders were so heaped with the damp white flakes. Old Ezra Barnet sat by the stove in utter despair, and waved a limp hand warningly toward the bedroom door.

"She's layin' in a sog," he said,hopelessly. "I ought to thought to send word to pore Ezry -- all the boy she ever had."

Mrs. Powder calmly removed her snowy outer garments, and tried to warm her hands over the fire.

"Put in a couple o' sticks of good dry wood," she suggested, in a soothing voice; and the farmer felt his spirits brighten, he knew not why. Then the whole-souled, hearty woman walked into the bedroom.

"All I could see," she related afterward, "was the end of Jane Barnet's nose, and I was just as sure then as I be now that she was likely to continner; but I set down side of the bed and got holt of her hand, and she groaned two or three times real desperate. I wished the doctor was there, to see if anything really ailed her; but I someways knowed there wa'n't, 'less 't was gittin' over such a jounce. I spoke to her, but she never said nothin', and I went back out into the kitchen. 'She's a very sick woman,' says I, loud enough for her to hear me; I knew 't would please her. There was a good deal to do, and I put on my aprin and took right holt and begun to lay about me and git dinner; the men-folks was wiltin' for want o' somethin', it being nigh three o'clock. An' then I got Jane to feel more comfortable with ondressin' of her, for all she'd hardly let me touch of her -- poor creatur', I expect she did feel sore! -- and then daylight was failin' and I felt kind o' spent, so I set me down in a cheer by the bed-head and was speechless, too. I knew if she was able to speak she couldn't hold in no great spell longer.

"After a while she stirred a little and groaned, and then says she, `Ain't the doctor comin'?' And I peaced her up well 's I could. `Be I very bad off, Harri't?' says she.

"'We'll hope for the best, Jane,' says I; and that minute the notion come to me how I'd work her round, an' I like to laughed right out, but I didn't.

"`If I should lose me again, you must see to sendin' for my son,' says she; `his father's got no head.'

"`I will,' says I, real solemn. `An' you can trust me with anything you feel to say, sister Barnet.'

"She kind of opened her eye that was next to me and surveyed my countenance sharp, but I looked serious, and she groaned real honest. `Be I like old Mis' Topliff?' she whispered, and I kind o' nodded an' put my hand up to my eyes. She was like her, too; some like her, but not nigh so bad, for Mis' Topliff was hurt so fallin' down the sullar-stairs that she never got over it an' died the day after.

"`Oh, my sakes!' she bu'st out whinin', `I can't be took away now. I ain't a-goin' to die right off, be I, Mis' Powder?'

"`I ain't the one to give ye hope. In the midst of life we are in death. We ain't sure of the next minute, none of us,' says I, meanin' it general, but discoursin' away like an old book o' sermons.

"`I do feel kind o' failin', now,' says she. `Oh, can't you do nothin'?' -- and I come over an' set on the foot o' the bed an' looked right at her. I knew she was a dreadful notional woman, and always made a fuss when anything was the matter with her; couldn't bear no kind o' pain.

"`Sister Barnet,' says I, `don't you bear nothin' on your mind you'd like to see righted before you go? I know you ain't been at peace with Crosby's folks, and 't ain't none o' my business, but I shouldn't want to be called away with hard feelin's in my heart. You must overlook my speaking right out, but I should want to be so used myself.'

"Poor old creatur'! She had an awful fight of it, but she beat her temper for once an' give in. `I do forgive all them Crosbys,' says she, an' rolled up her eyes. I says to myself that wa'n't all I wanted, but I let her alone a spell, and set there watchin' as if I expected her to breathe her last any minute.

"She asked for Barnet, and I said he was anxious and out watchin' for the doctor, now the snow'd stopped. `I wish I could see Ezra,' says she. `I'm all done with the lane now, and I'd keep the peace if I was goin' to live.' Her voice got weak, and I didn't know but she was worse off than I s'posed. I was scared for a minute, and then I took a grain o' hope. I'd watched by too many dyin'-beds not to know the difference.

"`Don't ye let Barnet git old Nevins to make my coffin, will ye, Mis' Powder?' says she once.

"`He's called a good workman, ain't he?' says I, soothin' as I could. When it come to her givin' funeral orders, 'twas more 'n I could do to hold in.

"`I ain't goin' snappin' through torment in a hemlock coffin, to please that old cheat!' says she, same 's if she was well, an' ris' right up in bed; and then her bruises pained her an' she dropped back on the pillow.

"`Oh, I'm a-goin' now!' says she. `I've been an awful hard woman. 'Twas I put Barnet up to the worst on't. I'm willing Ezra should marry Ruthy Crosby; she's a nice pooty gal, and I never owned it till now I'm on my dyin'-bed -- Oh, I'm a-goin', I'm a-goin'! -- Ezra can marry her, and the two farms together 'll make the best farm in town. Barnet ain't got no fight left; he's like an old sheep since we drove off Ezra.' And then she'd screech; you never saw no such a fit of narves. And the end was I had to send to Crosby's, in all the snow, for them to come over.

"An' Barnet was got in to hold her hand and hear last words enough to make a Fourth o' July speech; and I was sent out to the door to hurry up the Crosbys, and who should come right out o' the dark but Ezra. I declare, when I see him you could a-knocked me down with a feather. But I got him by the sleeve -- `You hide away a spell,' says I, `till I set the little lamp in this winder; an' don't you make the best o' your ma's condition; 'pear just as consarned about her as you can. I'll let ye know why, soon 's we can talk'-- and I shoved him right out an' shut the door.

"The groans was goin' on, and in come Crosby and Ruth, lookin' scared about to death themselves. Neither on 'em had ever been in that house before, as I know of. She called 'em into the bedroom and said she'd had hard feelin's towards them and wanted to make peace before she died, and both on 'em shook hands with her.

"`Don't you want to tell Ruth what you said to me about her and Ezry?' says I, whisperin' over the bed. `'Live or dead, you know 't is right and best.'

"`There ain't no half way 'bout me,' she says, and so there wa'n't. `Ruth,' says she, out loud, `I want you to tell pore Ezra that I gave ye both my blessin',' and I made two steps acrost that kitchin and set the lamp in the window, and in comes Ezra -- pore boy, he didn't know what was brewin', and thought his mother was dyin' certain when he saw the Crosbys goin' in.

"He went an' stood beside the bed, an' his father clutched right holt of him. Thinks I to myself, if you make as edifyin' an end when your time really does come, you may well be thankful, Jane Barnet!

"They was all a-weepin', an' I was weepin' myself, if you'll believe it, I'd got a-goin' so. You ought to seen her take holt o' Ruth's hand an' Ezra's an' put 'em together. Then I'd got all I wanted, I tell you. An' after she'd screeched two or three times more she begun to git tired; the poor old creatur' was shook up dreadful, and I felt for her consid'able, though you may not think it; so I beckoned 'em out into the kitchen an' went in an' set with her alone. She dropped off into a good easy sleep, an' I told the folks her symptoms was more encouragin'.

"I tell you, if ever I took handsome care o' any sick person 't was Jane Barnet, before she got about again; an' Ruth she used to come over an' help real willin'. She got holt of her ma-in-law's bunnit one afternoon an' trimmed it up real tasty, and that pleased Mis' Barnet about to death. My conscience pricked me some, but not a great sight. I'm willin' to take what blame come to me by rights.

"The doctor come postin' along, late

that night, and said she was doin' well, owin' to the care she'd

had, and give me a wink. And she's alive yet," Mrs. Powder

always assured her friends, triumphantly -- "and, what's more,

is middlin' peaceable disposed. She's said one or two p'inted

things to me, though, an' I shouldn't wonder, come to think it

over, if she mistrusted me just the least grain. But, dear

sakes! they never was so comfortable in their lives; an' Ezra he

got a first-rate bargain for a lot o' Crosby's woodland that the

railroad wanted, and peace is kind o' set in amon'st 'em up in

Law Lane."

V.

When Ezra Barnet waked on Christmas morning, in his familiar, dark little chamber under the lean-to roof, he could hardly believe that he was at home again, and that such strange things had happened. There were cheerful voices in the kitchen below, and he dressed hurriedly and went downstairs.

There was Mrs. Powder, cooking the breakfast with lavish generosity, and beaming with good-nature. Barnet, the father, was smiling and looking on with pleased anticipation; the sick woman was comfortably bolstered up in the bedroom. In all his life the son had never felt so drawn to his mother; there was a new look in her eyes as he went toward her; she had lost her high color, and looked at him pleadingly, as she never had done before. "Ezry, come close here!" said she. "I believe I'm goin' to git about ag'in, after all. Mis' Powder says I be; but them feelin's I had slippin' down the mow, yesterday, was twice as bad as the thump I struck with. I may never be the same to work, but I ain't goin' to fight with folks no more, sence the Lord 'll let me live a spell longer. I ain't a-goin' to fight with nobody, no matter how bad I want to. Now, you go an' git you a good breakfast. I ain't eat a mouthful since breakfast yesterday, and you can bring me a help o' anything Sister Powder favors my havin'."

"I hope 't will last," muttered Sister Powder to herself, as she heaped the blue plate. "Wish you all a Merry Christmas!" she said. "I like to forgot my manners."

It was Christmas Day, whether anybody in Law Lane remembered it or not. The sun shone bright on the sparkling snow, the eaves were dropping, and the snow-birds and blue-jays came about the door. The wars of Law Lane were ended.

From a letter to Annie Fields dated March 1889 (Fields, Letters

p. 42).

I got "Law Lane" in proof yesterday in excellent season for the

Christmas number, one would think. Mr. Burlingame hoped that I

could shorten it a little, and I have been working over it. He

has great plans for his Christmas number and there are many

things to go in. He seems pleased with "Law Lane," so is its

humble author, but you are not to tell.

[ Back ]

Scribner's Illustrations for "Law Lane"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This poem and illustration follow "Law Lane" in its original Scribner's publication.

NOTES

"Law Lane" was originally published in Scribner's

Magazine, December 1887, collected in The King of

Folly Island and Other People (1888), then reprinted in

Tales of New England (1890). According to Michael Davitt

Bell in his Library of America edition of Jewett's Novels

and Stories (p. 932), the Tales of New England

texts are less reliable than the first collection texts.

However, in this case, the texts of the two collections appear

to be identical. Where I have noticed probable errors in a text,

I have added a correction and indicated the change with

brackets. Except, in the case of farmhouse, which is

sometimes hyphenated, I have left the word as it appears in the

text.

[ Back ]

bottomless pit: See

Revelations 9:1-4.

[ Back

]

everlastin' bliss: Jesus Christ

speaks several times of those who will receive everlasting life

if they exchange their attachment to material and worldly things

for a primary attachment to God. See for example, Luke 18:29-30.

[ Back ]

light-horseman: lightly armed

cavalryman.

[ Back

]

powder-posted: Affected with

dry rot; reduced to dust by rot or by powder-post beetles..

[ Back ]

Ten Commandments: Exodus

20:3-17.

[ Back

]

lung-fever: pneumonia.

[ Back ]

sweet fern: Comptonia

peregrina; not a true fern though it has fern-like leaves.

[ Back ]

sweet-brier: a European rose

with big, strong thorns and a single pink blossom; rose hips

(the fruit) are a source of vitamin C and are used for jellies

and sauces; often stands for "poetry" in nineteenth-century

language of flowers (Research, Ted Eden).

[ Back ]

bayberry: Myrica. a

short, thick wild bush that grows along the coast in New

England; the wax from its berries is used to make scented

candles; represents "instruction" in nineteenth-century flower

language (Research, Ted Eden).

[ Back ]

witch-grass: Panicum

capillare, according to the 1913 Webster's unabridged, a

kind of grass "with minute spikelets on long, slender pedicels

forming a light, open panicle."

[ Back ]

pusley: Almost certainly, this is

Purslane, portulaca oleacea. Wyman's Gardening

Encyclopedia says, "Probably the worst weed troubling all

gardeners... It was introduced to Massachusetts from

Europe, as early as 1672 but now it is a recurring weed

everywhere. ...even when it is hoed out of the ground and

left on the surface of the soil, roots form again after the

first shower." (Research: Nancy Wetzel).

[ Back ]

mountings: mountains.

[ Back ]

love would still be lord of

all: Virgil in Eclogues X, line 69 says, "Love

conquers all things; let us too surrender to Love."

[ Back ]

all the hate of all their

folks is turned to love in them: This phrase seems to allude to

the story of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. See I, v,

142 "My only love sprung from my only hate!"; and V, 3, 292 "See

what a scourge is laid upon your hate; / That heaven finds means

to kill your joys with love."

[ Back

]

alpaccy aprin: probably

the apron is made of alpaca cloth, a thin cotton and wool blend.

[ Back ]

balm of Gilead buds: for the phrase

"balm in Gilead" see Jeremiah 8:21-2. The balm here probably is

Bergamot, Monarda didyma. The buds are likely to be

blossoms or leaves, which were commonly used to flavor drinks.

The Encyclopedia Britannica says the leaves were made

"into Oswego tea, a beverage used by the Oswego tribe of

American Indians and said to be the drink adopted by American

colonists during their boycott of British tea." The 1913

Webster's unabridged says, "The fragrant herb Dracocephalum

Canariense is familiarly called balm of Gilead, and so are the

American trees, Populus balsamifera, variety candicans

(balsam poplar), and Abies balsamea (balsam fir)."

[ Back

]

Mis' Much-afraid: Miss

Much-Afraid is the daughter of Mr. Despondency in John Bunyan's

The Pilgrim's Progress.

[ Back

]

in the Book of Job: see Job,

Chapters 2 and 3.

[ Back

]

lamb-kill: Kalmia

angustifolia, a variety of laurel that is poisonous to

livestock if eaten in large quantity.

[ Back

]

sarpent in the garden o' Eden: see

Genesis 3.

[ Back

]

Scottish border-frays: Border

conflicts between Scotland and England recurred from about the

10th century until the accession of King James VI of

Scotland to the English throne as James I in 1603, and there

were later rebellions that could also qualify as border

conflicts. One of the Scottish border counties usually involved

in these conflicts was Berwick, from which Jewett's birthplace

in South Berwick, Maine may have taken its name.

[ Back

]

a festival which seemed in that

neighborhood to be of modern origin: In New England, where

Puritan influence was strong, the festival of Christmas was

of comparatively recent origin. Puritan colonials had banned

celebration on Christ's birthday. By the time of the Industrial

Revolution, Christmas came to be widely celebrated in New

England.

[ Back ]

Fourth of July: United States

national holiday celebrating the signing of the Declaration of

Independence on 4 July 1776.

[ Back ]

Thanksgiving Day:

Thanksgiving is an annual holiday celebrated in the United

States on the fourth Thursday in November. It originated in

three days of prayer and feasting by the Plymouth colonists in

1621, although an earlier thanksgiving was offered in prayer

alone by members of the Berkeley plantation near present-day

Charles City, Va., on Dec. 4, 1619. The first national

Thanksgiving Day, proclaimed by President George Washington, was

celebrated on Nov. 26, 1789. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln

made it an annual holiday to be commemorated on the last

Thursday in November (Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia).

[ Back

]

"was the bringer-in and

founder of the reign of the higher life": The source of

this quotation is not yet known, but it echoes words of the

prophecy of Zacharias, John the Baptist's father, regarding the

as yet unborn Jesus in Luke 1:74-9.

[ Back ]

good-will to men: Luke 2:13-14.

[ Back ]

opodildack: opodeldoc, a soap

lineament that might also include a variety of other

ingredients. The Oxford English Dictionary lists the

following as typical ingredients in the middle and late

nineteenth-century: opium, alcohol, camphor, oil of marjoram,

oil of rosemary, ammonia. The usual effect is to warm the area

to which it is applied, though other effects might also be

intended, depending upon the ingredients.

[ Back

]

layin' in a sog: a sog is a

drowsy or lethargic state. The Oxford English Dictionary

locates the earliest use of the word in this sense in 1874 and

includes this example from Jewett, indicating that this usage

belongs to that local time.

[ Back ]

In the midst of life we are in

death: from the service for Burial of the Dead in The

Book of Common Prayer.

[ Back

]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College

| King of Folly Island Contents | Scribner's Text |