Main Contents & Search

A VILLAGE SHOP.

Sarah Orne Jewett

Madam Jaffrey in her later years always sat at one of her front parlor windows in the winter afternoons. But one day, many years ago, she was not there, and passers-by missed her kindly greeting or the smiling nod of invitation with which she was apt to favor her intimate acquaintances. One could not help being uneasy at her absence; she was an older woman than her years and like a piece of her own frail china. She had seen much trouble, but there never was a braver heart.

As you went by on the flagstoned pavement, you could see the south parlor at a glance. The delightful old-fashioned room was flooded with sunlight. If you lingered for a moment, you could look through and beyond the room itself, and see the old garden pear-trees whose fruit all Grafton knew. Where could Madam Jaffrey be? and where was Miss Esther Jaffrey this February afternoon?

The two ladies are sitting in an upper chamber together, and suffering the first pangs of a great disappointment. All Grafton knows the story of their pinching economies, and the cheerful sacrifice of their own comfort, and that these have been reckoned as nothing in their pride and joy at furthering the interests of Leonard Jaffrey, the only son and last hope of his house and name. Perhaps if the good unworldly women had known the increased expense of a college education, as compared with the prim figures in ancient family account books, they would have lacked courage for even this darling project of their hearts, but from the time of the boy's babyhood there had never been any question of his being sent to Harvard College. The Jaffrey men had all been graduates. Famous old Marlborough Jaffrey, the first of them in the colonies, was an Oxford student who forsook his scholar's gown for a new-world enterprise, and though money grew scarcer as the last of his grandsons grew older, the brave ladies looked forward hopefully to the days when their sacrifices would be returned to them four-fold. They thought of Leonard Jaffrey's ancestry as if it were a solvent bank of distinctions and emoluments in which he had a noble credit account. If he could not represent the actual wealth of old Marlborough, -- for this, in their poverty, might have been most alluring, -- he could at least reëmbody the shade of his grandfather, the great jurist, or, failing him, there had been well-salaried and devout clergymen. His own father had chosen this career lovingly and died young, but already famous; in the collateral branches of the family tree hung plenty of well-ripened fruit. But it appeared sometimes as if Leonard had descended not from these but from some less worthy infusion of sap; some heedless alliance which had been quickly overlooked and ignored had yet left its corrupting and perverting influence in the Jaffrey blood. This young scholar was a very Jaffrey to look at; you could make up his somewhat characterless face from the features of the family portraits -- a nose here, an eye-brow there, a lock of waving brown hair from his wistful-eyed father in gown and bands. Yet he had not the spirit of the Jaffreys, this Leonard who was the last of them, and it was only in sad and disheartened reveries that his sister was forced to acknowledge this melancholy deficiency. If she had been the son! she often said to herself with a surging thrill of pride and daring. If she had been the son how she could work and win her way, and not be the least of those who had borne the Jaffrey name unsullied! But she was only a woman, and the Jaffreys were more provincial than they used to be -- a Jaffrey of Grafton could not lead public opinion in unfeminine directions; she was not a social reformer but fiercely conservative at heart. She had denied herself everything that could be denied, but treated her mother like a queen in exile, and so with sinking heart and dwindling hopes they came at last to this day when a letter had arrived from Leonard to say that he had finally forsaken any intention of exercising his profession. His general studies would more than fill his time, and he had conscientious scruples against preaching the dogmas of the faith in which he had been reared and trained. And the two women knew that there was to be no such thing as persuading him to change his mind. The Jaffreys had always won their fame by their power of decision. Leonard had said I will not! and could hang back with all the steadfastness with which his ancestors had said I will! and then pushed forward to their goals.

Now the acknowledgment must be made that he had disappointed all hopes from the first. From the day that Miss Jaffrey with eager, elder-sisterly forethought had looked through the list of his classmates and rejoiced to find a Quincy, a Boylston, a Winthrop, or a Gardiner, and gladly planned for the resuming of old family alliances and friendship, only to find her brother uninterested and even reluctant; from the day when she sadly acknowledged that Leonard saw the world through strange eyes and was indifferent to the old home standards, she had been driven back inch by inch to the very stronghold of her opinions. She only held to her own instincts and the Jaffrey code all the more fiercely because there was a traitor on the very throne. Something must be allowed for the natural rebellion of a young man to petticoat government, but the fact remained that Leonard Jaffrey was indifferent to worldly honor, careless of the world's needs or its demands, in no wise public-spirited, and a strange bird altogether to have been hatched in the ambitious Jaffrey nest.

Fortunately the already aged and fading mother was not forced to stay long in this world to bewail the blasting of her hopes, and make futile excuses for her wrong-headed boy. By the time he came home from his theological school with a collection of miscellaneous volumes for which he must have practiced economies only second in severity to those which had kept him a student at all, Madam Jaffrey had but time to see him once or twice in her darkened room; to whisper that she forgave him her disappointment and respected his conscientiousness. Leonard vaguely understood these expressions, but her death, touched him deeply. Let us hope that he regretted his inability to win either gain or glory to lay at her feet, and saw at last in one swift flash of light, his own torpor, and the burden he had let this patient mother carry. He was only made more silent by the loss and change in his home, and there was a more impenetrable barrier than ever set up between him and his sister Esther. She was the eldest of a large family of children of whom all had died but Leonard and herself, and their relationship was somehow unequal; not that of a brother and sister who have constantly seen life from somewhere near the same angle. He was only too well aware of her noble rectitude and loyalty and her uncommon powers of mind, even of her good looks, which seemed to increase instead of paling with the march of years -- but he felt her generosity like a chain of steel, and the memory of her sacrifices and her opinion of his course burnt him like living coals. Perhaps he thought it wiser not to undertake a career in which he foresaw inevitable failure, perhaps it was simply that the natural indolence and love of a book-worm's life filled his whole horizon. He went away directly after his mother's funeral, for he could bear neither the sight of the empty rooms, nor the weight of his sister's stately courtesy, which only covered that sullen disapproval of himself that lay beneath. But to this sister he was still a Jaffrey, and however carefully she avoided meeting his eyes, she was able to speak of him serenely to her acquaintances, and to acknowledge without hesitation that he intended to lead the life of a student henceforth, and instead of following his profession had decided to become a man of letters. She liked to repeat the words, "a man of letters;" yes, Leonard was a Jaffrey and had a Jaffrey's right. But those who knew the household best puzzled their brains to know by what means it was to be sustained. The Jaffrey lands had shrunk to the limits of the old pear-tree garden and a strip of decaying wharf-property by the river; the Jaffrey fortune had been spent almost to the last farthing in uncomplaining furtherance of the scholar's welfare. Here he was, stranded in the old house with as much energy as a barnacle, looking already close upon middle-age from his lack of physical activity; the most unproductive man of letters in New England, with no apparent value either social or commercial. A step farther and he would only have become what the canny Scotsmen call "a stickit minister."

II.

There were enough of the old people left in Grafton twenty or thirty years ago to suffer an acute attack of pain and misgiving, when the news was whispered to and fro under the elms that Miss Esther Jaffrey intended to keep a ladies' shop. The immediate reason for it was so aggravating that a great deal of unkind comment flew about the indignant town; there was an unusual visiting from house to house, and some of Miss Jaffrey's own friends were heard to say sorrowfully that it would be more than they could bear to see her stand to serve them behind the counter. Her grandfather the judge's office, her granduncle's ministerial study; her own father's study, and the place that knew his youthful hopes, the writing of his famous and saintly sermons, and the burning of much midnight oil; what a degradation it seemed to put the old room to this new use. Besides this, had it not been the counting-room of Marlborough Jaffrey, the great colonial merchant? Here he had kept the papers of those busy two hundred-ton ships which had earned his fortune; here he lived his long and noted life, and defied wind and weather, time and tide, as he pushed forward his bold enterprises through half a score of distant seas. From the small-paned windows he could look far down the broad tide-river which seemed to dutifully dispatch its lazy waters toward the ocean and draw them back again twice a day in deference to his fleet of packets and gundalows, deep-laden with their out-bound or incoming cargoes. Those were rich and glorious days for Grafton, but nobody had made any money since. Not only the merchant's own descendants but everybody else had lived on the remains of their ancient fortunes, except for the yearly produce of the farms and a barely sufficient local system of petty commerce. The farms, the few large houses in the village, even the high-steepled church itself, had been paid for with money that had come in the Jaffrey ships. But it is long since anybody had chosen the business of sailor -- there are only a few slippery old sticks of oak timber left in the river-mud, and the fortunes have all dwindled away. The embargo gave a killing blow to the prosperity of Grafton, and spendthrifts and foolish men and women and the wear of time have been undermining the once secure investments ever since. The worst punishment fell upon the town's pride when no sooner had the news been told of a certain Mary Destin's giving up her business in small wares, than it was also known that Miss Esther Jaffrey had made definite arrangements to become her successor. Miss Esther Jaffrey, like Hawthorne's Miss Pyncheon had become reduced to the keeping of a shop. The bulwarks of social safety were broken down, and public opinion was ready to reproach the former owner of the business, since it was vaguely believed that if Mary Destin had not planned to go westward to live with a married sister, this catastrophe would have been averted. Her good sense in making the change was loudly questioned; there was a general feeling as if she had somehow involved another's ruin, that she ought to have remained in her own lot and place.

III.

Since we looked in at the parlor windows many things have happened, but there is no apparent difference in the room itself except that Madam Jaffrey has gone away. It is two weeks now since she died, and they have been two bitterly anxious weeks to the lonely daughter who has seen the small hours of nearly every night, and has wondered what her future could be until her brain has been fairly burning, and her eyes fixed wide open in a sleeplessness that seemed to drain her very soul of its strength. Nobody knew her sorrows now, save herself; there was no longer any incentive for keeping them back lest some one else might sorrow the more. She had nobody to keep cheerful for now, since her mother died. Loyal Betty, the one maid-servant, was dim and dull of wits, except in her own province, and she and Miss Jaffrey plodded their frugal way together with little conscious thought of each other. Betty's hero was Mr. Leonard, and yet she was taught by instinct to be silent about him before her younger mistress, even in the days when Madam Jaffrey took joy in telling of his poor triumphs and that noble future apparently now more remote than ever. Betty had been a great resource to the boy's mother; Betty saw no reason why the most improbable successes might not come to pass.

The house seemed very much too large nowadays, and it was a poor mockery when it was set in order, as if for guests, during the early summer. Some of the furnishings were already threadbare, but the old timbers were live-hearted, and the long purses of its earlier inhabitants had shaped it with the soundest and best wood and fabric of their day. Little need be spent on it for years to come, but this was a starved and sorry life compared with the earlier abundance, the luxury, the cheerful company, the busy maids and men of an earlier time. Just when the need of getting into debt came now like a crouching tiger into Esther Jaffrey's well-trodden path, the deliverance was also there, a melancholy alternative, but welcomed by her with all a Jaffrey's pride in independence and self-respect. It was indeed sad to think of shop-keeping at her age, and under the shadow of her family tree, but it would be much sadder to have no shop to keep, no way to look for deliverance from her poverty. Before the good people of Grafton had ceased gasping, and had half reviewed the resources of friends, and fitting employments which surely belonged to their leader, the goods of Mary Destin had become those of Esther Jaffrey, and the small projecting room next the sunny parlor which had been counting-house and study by turns -- this historic room which opened handily to the street was insulted by a stained wood counter and meagre show-cases, with boxes of thread and needles, and whalebone and edgings and all the minor wares that home-keeping women need in their daily work of mending and making. Miss Jaffrey's shop! would it ever seem right to say it -- could one ever mention its resources unconsciously, or dare to suggest better bargains? Mary Destin was a cheerful gossip and a born tradeswoman; she had gone away contented with the value of an ancient silver-set diamond ring safely pinned into her pocket. And yet Miss Jaffrey had not ceased to be a lady because she had begun to keep a shop. As one woman after another ventured in to make a necessary purchase after the first awed week, they found her more friendly and sympathetic than ever. She was ready to talk across the counter, to take a bit off her prices when she heard a lofty hint of the article being too expensive. She only listened with wistful eagerness when a story was told that a former resident of Grafton had given the old town a vast sum of money for a public library. The Jaffreys' day was almost over, but no jealousy of any new patrons seemed to be in her generous heart. In fact Miss Jaffrey now first became really known to some of the Grafton people who had wished through envy and conscious inferiority to take pennyworths out of her high reputation. They could not help being pleased with her lovely bearing, and her serene acceptance of her altered fortunes. And so the enterprise of her later life began with the sympathy and blessing of all who knew her. The familiar white-lettered black boxes of ships' papers that had belonged to rich old Marlborough Jaffrey were still perched in line on a high upper shelf that corniced the room. All his descendants had been proud to keep them there. Ship Esther, Brig Marlborough, Brig Brasenose, Ship Palatine, Ship Pactolus; how well Miss Jaffrey knew the long row; they were almost like funereal coffers that held the ashes of her ancestors.

During the second week after the shop was opened Mr. Leonard Jaffrey came home. He had already sent some of his books, and dimly expected to find them neatly placed on the shelves; now he brought more, and as he drew near the old house he looked with eagerness at the study windows as if there must be his true home henceforth. He had already planned the disposition of his treasures with rare enthusiasm; but he was suddenly aware of strange shapes and colors behind the familiar small panes. Could Esther have let the room to a stranger? He grew dizzy for a moment with uncharacteristic wrath, then he was smitten, let us hope, with regret. When the trunks were carried into the wide hall, and he stood uncertain what to do, feeling for once the weak man he was from his lack of force and strange inadequacy, Miss Jaffrey made her appearance. She was singularly gentle toward him, indeed was not she his protector and defender, had not she solved the puzzling problem of their being clothed and fed? And the sister and brother kissed each other with a softening remembrance of the mother who had loved them both and been patient with them, and from that day forward the shop was never discussed, or in any way berated.

IV.

It sometimes appeared as if nature had destined Leonard Jaffrey for a reservoir of learning. He was absolutely without any original thoughts or gifts, he was unproductive from the beginning, yet with unquenched appetite he devoured the wisdom and imagination that were stored between his book covers. Unsated, unflagging, unforeseeing, he became at last a perfectly unavailable treasury of other people's knowledge, like some lake that has no outlet. Yet there surely must have been an invisible exhauster of his hoards to correspond to the lake's evaporations; not speech, for he grew silent and withdrew more and more into himself as years went by. Miss Jaffrey was much the gainer by her increased facility for intercourse with all sorts and conditions of women, but the brother seemed to have let his individuality ooze out to the dry pages of his books as if they were a species of treacherous blotting paper, and destined in time to completely absorb him. He never asked his sister for money, but she spared him what she could. Was not that one cause of the shop? Sometimes he looked at her very wistfully as he put the price of her self-sacrifice slowly into his pocket, and vaguely called up a feeble ghost of his purpose to more than make things up to her by and by. But when his pockets clung together for very leanness, and some longed-for pile of dusty volumes was slipping out of his grasp with every hour, he even found himself greedily gazing at the shining silver tea-service of which he and Miss Esther were the sole heirs. Packed away in the sideboard were useless porringers and tankards -- yes, he was quite capable of selling the whole of the Jaffrey plate in these moments of anguish and limitation. He was a book-miser at last. It was a mercy that he lived in Grafton, for the vicinity of book-stores and ragged companies of volumes on corner stalls of the great towns would either have made him mad or a hardened offender against justice.

As the years slipped by he gained some little reputation as a scholar, quite unworthily, for he was too firmly grafted into his position as idle accumulator and reader to exercise his stunted powers of thought. He was only a personified memory with no gift at combination and association; an encyclopædia, a very rag-bag of true and worthless knowledge; and the easy life which made no continuous demands upon him seemed to hold no inspiration in any of its lights or shadows. The library slowly grew, the man himself really dwindled, yet he was thought a much wiser and more awesome person than the resolute and gentle sister who kept her petty shop as intently as that famous grandfather had managed his shipping. She was secretly glad to spend what energy she could upon the slow little business, and tried to fancy that she was by nature a business woman. Yet she at first insisted upon the old family custom of reading aloud, and so upon sharing as much of her brother's evenings as possible. Sometimes she was interrupted, but as a rule her own evening leisure was respected, and the solitary lamp on the shop counter hinted that no errands except those of urgent necessity were expected or provided for.

If the brother was glad that their mother had not lived to be wounded by the sound of the tinkling shop-bell, Miss Jaffrey was rejoiced that she had never been forced to surrender all hope of her son's gaining distinction. But toleration and good breeding kept a harmonious atmosphere in the old house, and on summer Sundays, when there were strangers in the village, admiring neighbors still pointed out Mr. and Miss Jaffrey as the most interesting figures in the congregation.

For a long time there was little

change in the quiet old village, but there came a day when

everybody acknowledged that Grafton was waking up. It has

already been hinted that a large sum of money was left in trust

for the building of a public library. The old academy, well

endowed and famous along the line of its earlier history, seemed

to take a new lease of life, and as in days of the past, a

successful teacher drew round him the brightest boys and girls

of the neighboring towns. There were more and more people, too,

who discovered the beauties of the wide tidal river and its

wooded banks; and from the neighboring resorts on the seashore

near by, increasing numbers of summer idlers came inland like

birds of passage to linger for a while in the shade of the great

Grafton elms. The time-honored repose of the village seemed

permanently broken, and not the least attractive figure was this

stately Miss Jaffrey who had achieved the dignity of

self-sacrifice in willingly supporting her learned brother. It

was considered a true romance when the village people discovered

this aspect of the shopkeeping through the help of others. They

were delightfully eager to enlarge upon the old-time majesty of

the Jaffreys and the slow succession of its assailments.

Lookers-on could only guess at the self-denial which made it

possible for the dear lady to do her part in giving for the good

of church or state, or to carry forward, even in simplest

fashion the old-time hospitalities and generosities of the

house. But what she gave she gave royally,

and with that cheerfulness which the

Lord himself loves. The bright young people were a great

pleasure to gray-haired, dignified Miss Esther, as they went

flitting about the streets in their gay gowns, or lingered in

her shop with sweet sympathetic looks. Some found their way into

the parlor and learned to know the rest of the fine old house,

and were even graciously entertained at tea to their hearts'

delight and admiration. More than one descendant of the house's

old acquaintances carried away to Boston a glowing description

of this fine gentlewoman, in her nobly equipped dwelling, and

the pathetic unworthy business of her life. The brother did not

lose charm from the fact that he was seldom seen and was still

in middle life, with the manly beauty of the painted Jaffreys on

the walls. But as winter took the place of summer, and these gay

guests disappeared like butterflies, the village seemed more

familiar again, and as if it had turned over for another nap.

The walls of the new library were rising, Miss Jaffrey liked to

hear the clink of the masons' hammers, and one day thought

sorrowfully that she was growing old and there was no one to

follow herself and Leonard in the Jaffrey house. There was one

comfort, he had not gathered his books for nothing, she would

urge him to decide to leave them to the town by and by when

Death called him away for his sins to a bookless world. She

herself had not been worthy the name of Jaffrey, there was no

reason why anybody should remember her; but she had kept her

house generously and her shop honestly. "Perhaps I had to be

punished for my pride," she thought, at the wistful remembrance

of a proud and hopeful girlhood. The elder ladies of Grafton

were fond of saying to each other with gentle emphasis, "You

know, Miss Jaffrey understands what ladies care for!" This was

the gift of her ancestry then -- a delicate power of selecting

linen, cambric, or soft ribbons? Was there, beside, a trained

capacity and usable force which some persons of less illustrious

descent found themselves without? She was the chief literary

authority of the town, though it was acknowledged that her

brother was more available for serious questioning. The

old-fashioned book-club had its headquarters in the shop, and

the best talk and best influence in Grafton resided under Miss

Jaffrey's roof, -- in truth her own ladylike, apologetic little

head-dress thatched it in. Yet, alas, there were some new shops

now in the new part of the town. Miss Jaffrey had a mere trifle

of money for the rainy days of her fast approaching age, and yet

she had been careful and wise and self-denying all the way. She

was almost proud of the bookworm overhead instead of being

indignant with him; she never reproached her brother, it would

have broken her heart if he had gone to shopkeeping. "Yes,

Leonard is man of letters," she used to say with smiling

indulgence. "One cannot expect business gifts in him with all

the rest." She began to dream now of his making a proper

marriage. It was partly for this that she planned her summer

tea-parties.

That winter brought new problems. Betty was really old, and for the first time in her life fell ill. Miss Jaffrey overworked herself and had to close the shop for many days together, and at last hired an inadequate young girl to tend it in her place in order to serve Betty, herself. But Betty was only enraged at such officiousness, and the shop was quickly put into dire disorder. Miss Jaffrey was in real distress for a time; but after a while the clouds blew over, and she was left with a miserable fear of the repetition of such dark days. Several of her best patrons and most valued friends had died; time was fast assailing her security as a business woman. What had she to look forward to but dependent poverty, the sharpest sorrow that old age can bring to a woman of her nature. Yet Leonard did not suspect these anxieties. He ate his methodical breakfast and took his methodical walk and made his accurate notes in a clerkly hand, catalogued and re-catalogued his books, and lived his peaceful life. Sometimes he noticed that his sister had changed in outward looks, but it never occurred to him to ask the reason. They walked into church on Sunday with widely different feelings -- the woman's heart crying for help and, for the second time, driven to despair; the man comfortable, unapprehensive, and ready to quibble with the clergyman about the emphasis of a Greek word or incorrect quotation from one of the early fathers. Miss Jaffrey climbed to the garret once to look at a disused set of heavy mahogany chairs; if worst came to worst, she would write presently to a young summer friend who had delicately suggested her ardent desire to buy such fine old furniture. Leonard would not miss the chairs. As they sat opposite each other at tea-time, Leonard being also a silent sufferer for more books, the tea-urn winked and blinked at first one and then the other, as if conscious of its solid worth. It was secure in the belief that its owners were capable of starving before their empty plates rather than sell it to a stranger.

V.

One winter day a man came driving slowly up the wide Grafton street under the leafless branches of the elms. For some time before there had been no other passerby, and the people who sat at their windows looked out with mingled relief and curiosity at the small old-fashioned sleigh and heavy, slow-stepping horse. It was certainly very dull in Grafton in winter weather, and in a cold clear day like this when the snow on the house roofs refused to melt, as every one said, "in the eye of the sun," there was little going abroad. Several house-bound women, eager for something new to think about, flattened their foreheads against the cold window panes to see where John Grant was going. He was a rich farmer from a comfortable home of his own two or three miles below on the river shore, a widower these dozen years, and well known in the village.

"He's turnin' up by Miss Jaffrey's shop," said one observer. "I hope he's goin' to buy her out, I'm sure. Time was that most all the farmer's folks used to trade with her, but they've been tolled off to the new stores down by the factory, and she must find it dreadful poor pickin'. Hard, ain't it? but then she might make some effort to keep up with the times, and get some sort o' fancy wares."

Miss Jaffrey herself was sitting in her sunny parlor trying to busy herself with some mending; there was little making to do now, the year round. She gladly saw John Grant stop and fasten his horse, then a shadow dimmed her eyes as she laid down her work and went toward the shop to meet him. There was no fire there; for three days she had done almost no business, and she could not waste the firewood. Brief errands could be done in spite of the cold; she would trust to the forbearance of her customers, and she had just been almost congratulating herself that no one had yet appeared. In mild weather the place of business could easily be warmed by the parlor fire, but John Grant might be chilled after his drive. With ready hospitality she only waited until he had knocked the last lump of snow off his sturdy boots and shut the shop door behind him, before she asked him to come into the parlor to warm himself.

The kindly pitying heart of the man grew very sad as he looked at his hostess; standing before her half-empty shelves, he hesitated a minute as if it might be kinder to ignore the cold, then he saw how thin and gray she looked, for the quaint, three-cornered shawl round her thin shoulders was not preventing one shiver after another. He followed her somewhat bashfully into the next room and unbuttoned his coat without speaking, though he bowed with sober dignity as Miss Jaffrey placed a chair for him before the Franklin stove. It was quite another atmosphere in every respect from that in the shop, but while the eyes of the portraits and the presence of a lady were trying at first to his composure, they quickly confirmed him in his secret purpose.

"I called to see you on a little private business, Miss Jaffrey," said good, sensible John Grant, after they had decorously considered the weather. "I am going to ask a great favor at your hands." Miss Jaffrey looked anxious at first, then relieved. The Jaffreys liked to grant favors much better than to receive them, and she felt strangely at the world's mercy in these days.

"I shall be very glad if I can do anything to serve you," she said, simply.

"I hope you will not think I mean to presume too far," the plain man said, with grave deference, and almost courtesy, entirely different from his cheerful farmer's manner. "You know that I have only one girl at home? She was the baby when her mother died, a little child following me about, hardly above my knee, and I couldn't seem to do without her for long at a time, so I haven't taken the thought I should about her education till here she is a young woman. She has taken what schooling she could get in our district, and she's a great hand for story-books, reads everything she can get. And I see all too plain that she shows some lack of woman's care. I'm well enough off to send her to some o' the smart boarding schools, but I can't seem to make up my mind to it. Some young fellow'll be picking her off," -- this with a wise twinkle of his eye at Miss Jaffrey, -- "but I mean to keep her while I can. Now, there's this good teacher at the academy and all the chance she really needs. If you could see your way to taking her and giving her a little good advice and letting her have the profit of seeing how a lady like you behaves herself, I should be -- well, more obliged to you than I've got words to say."

There was a moment of silence before Miss Jaffrey gave her answer. The speaker grew a little anxious, and feared that he had been, as he first suggested, presuming. There had long been cordial relations between the Jaffreys and the farm by the river. It was his grandmother's pride to tell how the Madam Jaffrey of her day brought gay parties to eat strawberries and cream, and had once done the gracious favor of showing all her own treasures of china to the admiring farmer's wife. Courtesy and mutual regard and dependence there had always been, but this sort of equality, never; and yet the shop and the unstemmed flood of poverty and anxiety remained. The petitioner had truly meant a kindness to Miss Jaffrey as well as a favor to himself; his pretty Nelly was good enough for any household.

Miss Jaffrey turned from the half-moon table where she had been fingering her sewing work in an aimless fashion. "I should indeed be very glad to have her come, if" shyly, "you think she will be contented. We are a sober pair, my brother and I, but he will be able to aid with her studies. I will not try to conceal from you that it will be a great help to me; I have been anxious lately about" -- but the sentence was never ended. "She has a sweet young face."

The father's heart was quickly touched. He could hardly have told why the simple occasion affected him so much. He had already noticed that the fire was made of chilly bits of the old pear-trees which had been broken by winter winds, and determined to send an honest load of his own whole-hearted rock-maple wood for Nelly's benefit as well as the Jaffreys'. The certainty of the old house's poverty, and an empty cellar beneath made him warmly resolve to provision it as for a siege. All his generous lavishness should work its will. Miss Jaffrey's grandfather, the judge, had saved his own grandfather from ruin, and he ought to have been seeing what he could do for this poor lady in her pinched housekeeping. It was hard to come down from a delightful level of talk about Nelly's needs and prospects and insistence upon paying a good price for board in view of her rare advantages, but at last, when the interview was ended, John Grant bought Miss Jaffrey's entire stock of fine handkerchiefs by way of a gift for his daughter. It was such bleak weather in the shop that he tried to shorten the process of sale by stuffing them into his deep coat pocket, but Miss Jaffrey insisted upon wrapping them with proper precision and figuring their cost on a bit of paper which she would have him audit with care. Her own fingers stiffened all too easily at the least chill. Could it be possible that Miss Jaffrey went hungry now and then to make her scanty larder hold out the longer? Oh, good John Grant, you were an angel that day, in disguise of your worn fur cap and warm, faded old coat with its big buttons! And Miss Jaffrey sat in the winter sunshine and cried as the old sleigh bells jingled away again out of hearing. Now she had surely seen her darkest day, and things could never be so hard and trying again.

In the twilight brother Leonard came down, unusually fretful, because his lamp held no oil, and he had been obliged to lay by his work. "Betty told me that we had no more, but I could not send for any," said the patient sister. "I have a little money now, however; Mr. Grant has been a good customer."

"I do not see any objection," Leonard Jaffrey gave kind assurance, after the new plan had been detailed with not a little apprehension. "Nelly Grant has a pretty face like a spring flower," he added, with unexpected sentiment, this elderly bookworm whom nobody suspected of knowing one young parishioner from another in the old Grafton church.

Betty alone was daunted at the prospect. "There's no knowing what work she and her mates will make trapesing through the house," the bent old woman grumbled. "I thought 't was time to end this playing' of keepin' shop," she added to herself later. "We should all have starved pretty soon, like a nest of frozen mice. An' see if I don't hint round an' spy if they ain't got some o' them big pippin apples at the farm, now, that old madam used never to be without. They do make proper dumplings and sliced pies."

VI.

Mr. Leonard Jaffrey stood behind a closed upper window one rainy April day, indulging himself in a fit of complete idleness. His sister still regarded him as a youngish man, but he had long since passed the time when one could justly call him anything but middle-aged. There was a becoming lustre of whitening locks against the original dark brown of his hair, and his complexion was like a girl's in its freshness and unmanly absence of any traces of exposure to wind and weather. Student life had evidently agreed with his constitution of body as well as mind. He smiled placidly as he looked out across the brown-budded pear-trees, and noted the hour on the steeple clock of the old academy. Everywhere in Grafton the Jaffreys might be reminded of their ancestors, for the needs of church and state had always been liberally considered as long as there was any money to give. Judge Jaffrey had handsomely endowed the ancient parish, and had given the very steeple clock itself to which his great-grandson now listened as it struck three. It seemed a fitting return of such favors on the part of the family that a poor boy who had grown rich in the western country should have chosen a public library as his monument. Grafton as a town was not especially dependent upon literature, but when the last of the Jaffreys proved to be a scholar, public notice was naturally taken of it, and the old-time favors would now be suitably returned. But the last of the Jaffreys gave the question no definite thought as he cast a sidewise glance at the new library's roof, and contemptuously reminded himself that there would probably never be a collection of books under it which would afford him much interest. Trivial modern volumes of transient worth were all that his fellow-townspeople might be expected to select. It did not naturally occur to this learned gentleman that his own duty lay in the direction of wise counsel and devoted interest; to him the practical affairs of life or any sense of personal obligation were as foreign as the problems of astronomy to a blind man. Through the recent struggles of his own family life, through years and years while Miss Jaffrey had crept painfully along the narrow path between want and tolerable comfort, he had been as unconscious of her makeshifts and anxieties as if he had been an Indian brave whose round-shouldered squaw existed for nothing but to carry tentpoles on her back, and to provide their necessary food. Yet he was sublimely conscious of much tenderness of heart, and proper interest in the human race. His world was a book world, not peopled with material shapes. While he stood at the window one could not help being struck by the neatness and quaintness of his attire, for the clothes he wore expressed a man who rightfully belonged to an earlier generation. He might have been the despair of a fashionable tailor, with that almost instantaneous process of assimilating his garments to the out-of-date spirit underneath. There was an odor of old leather books about his overcoat when he stood meekly in the Grafton post-office, or conscientiously drifted with the crowd toward the place of voting on town meeting days. As one glanced about the room upon which his back was turned that cloudy afternoon, it presented a curious appearance, and it was impossible not to be reminded of certain shell-fish whose covering thickens with age. No wonder that a suggestion of brown leather bindings followed him in his rare progresses into the outer world, for here there were hundreds shelved in crowded lines, piled in small toppling precipices against the wainscoted walls, and stacked in sliding hillocks here and there on the uncarpeted floor. Leonard Jaffrey himself could find his way among them, even in the dark, like a soft-pawed pussy cat; the noise of a fallen book was the only sound that roused his anger. There was apparent danger for a stray visitor, as if in time this floor and walls of experienced volumes would suddenly close in and stifle the room's occupant. The mahogany bedstead was furnished with a wooden canopy draped with faded blue damask, and armful after armful of books, for which there was no other lodging, had been stowed away on the top, next the ceiling. The apparent method of reaching them at such an inconvenient height was by climbing the slender, carved mahogany posts, but it would be difficult to fancy the dignified owner sliding carefully down to the floor after a season of reference and review of his celestial authors. A discerning eye might have shrewdly noticed one evil-disposed work which had slipped out from its pile on the burdened tester until it seemed to be wickedly just holding itself back until it could drop fatally upon Mr. Jaffrey's head just as he intended to retire for the night. There was truly something evil in the way it bravely held its dangerous weight high in air, or risked the possibility of gathering more dust.

The scholar at the window leaned closer against the sash as if something attracted his attention. Those who were quick enough to look over his shoulder could have caught a glimpse of a young girl who went with flitting step along the sidewalk next the old garden. The fence was unfortunately of solid boarding, and was far from being transparent, even after many years of necessary wear and moss growing. At the top it was cut in sharp points, and the girlish face moved quickly past in full view. The watcher drew back into the shelter of the window shutter, but his face had noticeably brightened. As he went back to his seat beside the table which held his writing materials, it was impossible to resist the suspicion that this was not the first time that he had seen Nelly Grant on her way home from her afternoon lessons at the academy.

A few moments later there was heard the familiar groaning creak of the old front door, and the noise of its decided closing. Mr. Leonard Jaffrey half rose from his wooden arm-chair, which was made altogether of serviceable slender rungs, then he regretfully sank back again with an almost bashful look upon his face. He waited listening intently, but he was not gratified by the sound of approaching footsteps. It seemed as if the mist which had followed an earlier rain were making the old bedroom-library almost too dark and dismal to be borne, and he drummed on the table fretfully with his familiar penholder.

Miss Jaffrey greeted her young housemate with a cordial smile of welcome as she came in, rosy and smiling, from the street. Nelly was very much of a little lady, and, with the help of numerous visits to the farm, had managed to be perfectly happy in the imposing Jaffrey house. She inquired now whether her father had made his appearance while she had been at school, and heard that nothing had been seen of him with hardly a shade of disappointment. "I told him to stop for me if he came over this afternoon," she explained; "but I don't believe he cares about bringing me back so early in the morning in this rainy weather." She was kneeling on the window-seat and looking eagerly up and down the deserted street. "You must go and take off your damp clothes," advised Miss Jaffrey quietly. "I don't want to send you home with a cold;" but the healthy country-girl only laughed, and made no other reply. "What do the school-girls want with so much of that narrow tape?" asked the elder woman timidly; for Nelly had fallen into a deep revery, as she still knelt in the window.

"Oh, it's a notion about a kind of stiff little trimming; they sew it together in pointed patterns. I'm sure I never should have patience to do it. Why, have they been here for some?" asked the young lodger with eager interest; for she had already learned to share in the satisfaction that followed a day of good sales.

"Yes, they came like a flock of pigeons an hour or two ago," answered Miss Jaffrey. "I happened to have a box full of narrow tapes put aside, of the very best quality too, and they pounced upon them gladly. I think I have had those little tapes ever since I kept the shop at all" -- she added by way of reminiscence -- "dear, dear! how many years it has been now, yet I somehow always think of it as a new thing, and the bell always startles me a little."

"I suppose it has been a good deal of company to you," replied Nelly with a vagueness in her tone that implied her intention of changing the subject. "I'm so confused about my mental philosophy lesson Miss Jaffrey," she announced with sudden bravery. "I wonder if Mr. Leonard would explain it a little?"

"Perhaps you would do as well to wait until the evening now," the mistress answered respectfully. "He never likes to be interrupted."

"I must study my Latin then," said the girl, with something like a pout. "He always says that I may come up at any time, and if he is too busy he will say so. I don't see any sense in mental philosophy, any way. I like things that belong to out-of-doors."

"I dare say you are right about asking him now," said Miss Jaffrey after a moment's pause. Her brother's learned exposition of the Baconian philosophy the evening before in that pleasant parlor had been to her very dull and unrewarding, but she was only a plain, uninstructed woman whose choice of reading ranged through the humbler level of fiction rather than among the mandates of the philosophers. The young girl gathered her books with alacrity and went up the wide hall-staircase. There was one step that announced her coming by a peculiar creaking sound, and when Leonard Jaffrey heard it, he fairly ran to open his door.

Miss Jaffrey was possessed by an unusual spirit of thankfulness when she was again left alone. Life had been so much easier for them all since Nelly Grant became a member of the household; they all seemed revivified by her fresh young life. She was a mannerly child, surely, and had been so considerate about making extra trouble, and forcing her own companions and personal concerns into undue prominence. It was good for Leonard to have this new interest to draw him away from his books. He really had seemed in excellent spirits of late, and lost the elderly look that he had begun to wear. "What an advantage his society is to that girl who knows nothing of the world!" thought the admiring sister as she creased down the edges of a collar. Leonard had really for once noticed that he needed a new article of raiment, and had even advised a slight modernizing change in the old collar pattern. Dear, unworldly Miss Esther Jaffrey -- where were your woman's wits!

In spite of Leonard's variation and deflection from his sister's ideal of the last of the Jaffreys, she still looked forward confidently to some less and less possible change. In one of the great camphor-wood packing chests lay a silk Geneva gown of which the folds grew sharper and the texture more limp year by year, but Miss Jaffrey touched it tenderly every spring and fall in her careful housekeeping as if the day might still come when Leonard would soberly deck himself in the ancestral garment. But the Geneva gown had long ago been too narrow for his plump back; it was cut for a slender, dutiful ascetic.

Sometimes Miss Jaffrey folded her hands in her lap and looked at her brother with pleased wonder at his vast learning. She tried to make it real to herself that he could read Greek and Hebrew and was way-wise in the most perplexing by-paths of ancient history. She was blessed with the gift of reverence, was Miss Jaffrey, like many another woman of her generation. She would have found it convenient if Leonard could have bestirred his feeble muscles enough to drive a nail straight or grapple with a rusty screw, but she never reproached him, and learned to use a hammer herself instead. With Nelly Grant's veneration for the scholar, her own pride and pleasure bloomed afresh. She was thankful to have her brother get a glimpse of fresh young life; it was in every way desirable to give him a little change from his books and creaking pen.

It was plain that Mr. Leonard Jaffrey himself was by no means averse to such refreshment. He became unwontedly agreeable, and lost a good deal of the dull expression of countenance and heaviness of motion which were the result of a good appetite and dangerous lack of exercise. As the spring days grew longer and brighter, and the snow disappeared and the early frogs piped loud and clear in the river marshes, Nelly besought her tutor and governor to take a walk after tea down the river road. She wanted to talk about her lessons, she said, and she hated to be shut up in the house all the time, now that the pleasant weather had come. It was such tiresome work studying, but she liked to have people tell her things that one ought to know. And Mr. Jaffrey amiably accepted her invitation, and took a stalwart ancestral walking stick from behind the hall door, smiling all the time at Nelly's girlish opinions of life.

Somebody jingled the shop door-bell impatiently for the second time and scuffed her feet about on the clean floor, and Miss Jaffrey obeyed the summons as if she were in a dream. She had watched the two figures depart up the street under the budding elms with a strange feeling of bewilderment, as if the air she breathed there at the parlor window held a kind of dull intoxication. She was vaguely afraid that poor little Nelly might grow over-fond of her stately companion, but the fear was driven away during an interview with a loquacious customer. Leonard would gravely discourage any silly feeling that a young girl might have. Miss Jaffrey smiled; for herself she would as soon fall in love with her brother's great dictionary as with himself. With all his worth, he was not her idea of a lover -- and the dear soul blushed as if she were as young at heart as Nelly herself. Besides, the Jaffrey dignities sailed as high as the moon over the head of society in general, and Nelly did not even belong to Grafton society, dear fresh-faced little country-girl! The shop-bell jingled again and again. All feminine Grafton seemed to be in need of pins and needles. One or two of the women who lived along the street said meaningly that they had seen Miss Jaffrey's brother go by a little while before. But Miss Jaffrey responded with very little interest, as she counted out change or buttons for her curious customers. At that moment the scholar and his young admirer were strolling in the odorous dampness beside a long row of willows made shadowy by the twilight. "I get into such a hurry for the flowers to come at this time of the year," said the girl impulsively. "To my thought there is no flower so sweet as a youthful face," said Mr. Leonard Jaffrey. "You have made a constant spring in our quiet lives." And Nelly blushed as bright as any rose of the June for which she was waiting.

A spirit of eager youth drove away all the shadows and haunting ghosts from the Jaffrey house in that bright May weather. The young girls of the academy flitted in and out of the doorway, at first awed by the atmosphere of stateliness and fading grandeur so foreign to their more prosaic modern lives. Nelly was very popular among her classmates, and had a way of asking them to the farm by twos and threes to spend the Saturdays and holidays of term time. They felt much more at their ease in such surroundings, and secretly admired their hostess because she was so completely unawed and at home with severe Miss Jaffrey and her hermit brother. Miss Jaffrey was patient and affable in her place of business, but it was quite another matter when she rose to receive you in her parlor with that grand manner and simple welcome. The old house was always pleasant in the spring, and its mistress now found herself unusually cheerful and hopeful. She hardly dared to look forward to the time when her young housemate must disappear, not only with her gay young train, but with her generous contribution to the slender revenues of the housekeeping. There was a delightful reminiscence of the past in all the intercourse with the farm. John Grant himself had been reared in all the ancient spirit of respect and even reverence for the Jaffreys, and never ceased to show it or to acknowledge Miss Esther's kindness and condescension to Nelly. But he had a great respect for the Grants, too, and looked upon them as people who never need be ashamed of themselves or their forefathers in any company, being people who paid their debts and did their duty in the place to which it had pleased God to call them. And John Grant the rich farmer and honest selectman of Grafton was as proud of his pretty girl as if she were a princess. He gave himself great credit for having hit on the best of all plans for bringing her social gain and pleasure in her last year at school. He was as fond of the old place as any man could be of his home, and hated the thought of leaving it for a night; but in the early autumn, after the crops were under cover, he meant to take Nelly a journey to New York, perhaps even to Washington and Mount Vernon, that Mecca of every old-fashioned American's pilgrimage. Once he was for a moment possessed of a glowing thought that it would be well to invite Miss Esther Jaffrey to make one of this adventurous party, but his good judgment rebelled. That would be taking a social liberty: with whatever appreciation of kindness, Miss Jaffrey would be sure to instantly decline. It was not John Grant's habit to ask favors that must be refused, but he was none the less loyal to the first lady of Grafton.

VII.

Spring came to Grafton like an unannounced young guest who steals into a dull dismantled house and surprises the inhabitants with a charming gayety and laughing voice, with a disorderly litter of fresh flowers and greenery all about the bare prosaic rooms. Nelly herself might have personified in advance the welcome change of season, and nobody greeted the coming of spring with more joy than the young girl, who went singing up and down the stairs, and brought in Mayflowers and anemones until Miss Jaffrey seriously announced that there was no longer an empty china mug or flower glass in the closets.

New England people are never quite sure that they may not have another snow-storm until a certain day of movable date when the sun shines and the dry ground settles itself with a determination not to be mistaken. This day usually comes early in May, and gives conclusive evidence that winter is fairly gone. It is not a day when one can comfortably exert one's self, it is too much like summer. Only yesterday the east wind may have been full of shivers, but now Miss Jaffrey and Betty were busy in the upper part of the house, suffering more or less from the heat and from the cares of spring housekeeping. The fragrant air was blowing through the rooms, even Mr. Leonard had opened his window a little way, and propped it by a too thin book that was slowly bending together under the weight of the heavy sash.

The unseasonable heat did not end with the close of day, but a summer-like evening followed, lighted by a full moon. Everybody was out-of-doors, and though Miss Jaffrey was tired after her busy care-taking, she was kept in the shop until long after eight. The academy girls were weaving a fine romance about her of late, and liked to come to buy her wares. In June would be the great exhibition day, and their hearts were already more concerned about their white gowns and their outward decoration than about the improvement of their unscholastic minds. They hushed their chatter and put on a more decorous and deferential manner as they came into Miss Jaffrey's presence, but they smiled at each other, and understood a great many things without speech, the elder woman and the gay girls. Miss Jaffrey was very glad when her revenues were all collected; the long street was empty at last and silent, the young people had all gone home, and when the last garrulous neighbor had disappeared it was a great satisfaction to step from behind the counter and close the shop door and put the strong cross-bar in the sockets. When the light was out and the two or three chairs were pushed back against the wall, Miss Jaffrey gave a deep sigh, and thought that she would just look at the evening paper and then go to bed. She was really very tired. Almost always when there was a busy evening Nelly took pleasure in coming in to help her. To be sure their nearest approach to a misunderstanding had followed a gentle reminder that the parlor, not the shop, was the place for Nelly to receive and entertain her friends, and there had been a subsequent day or two of cloudy weather. The shop was much less demanding in a social way than the rest of the house, one must confess. But Nelly was busy with her lessons nowadays, and quite solemn and cheerful by turns about the approaching end of her school life. Mr. Leonard was obliged to render a vast deal of assistance. Either Nelly was stupid with her book or he was beginning to squander his time. Miss Jaffrey felt a sense of uneasiness as she stepped into the parlor. There was no light there yet, though it was so late in the evening, and she stumbled against a strayed footstool. The glass door that led into the old garden was wide open, -- somebody had taken the trouble to force back the heavy inner shutter that was always drawn across the lower part of it in cold weather. Miss Jaffrey went to the door-sill and looked out. It was ridiculous in the girl to behave as if summer were already here, she would take cold in the dampness.

There was wonderful beauty in the familiar outlook, and Esther Jaffrey forgave the careless young offender as she herself yielded to the temptation. The air was deliciously soft and warm, there was a caressing sweetness in the fragrance of the old pear-trees which were standing like white ghosts of themselves all in full bloom in the moonlight. The box was sending up its heavy quaint odor -- the lines of its winter-faded leafage led straight down the old path where the mistress of the house had walked to and fro on many nights like this. She stepped outside the house and stood under the first St. Michael's pear-tree, and drew a long breath close to its lowest branch. "How the old things keep on blooming!" she thought, with a rush of feeling at the remembrance of her own faded youth.

Two figures leaning close together came out of the shadows beyond a high syringa thicket. Miss Jaffrey's heart stood still. They were lovers, they were whispering to each other, and the man held the woman to his heart and kissed her. Leonard Jaffrey and Nelly Grant! the moonlight made them look the same age. Leonard's late springtime was in full glory of flowering and delight.

"What does this mean?" cried Esther Jaffrey in a voice that seemed strange to her own ears. "Nelly, you must go in at once. Leonard! Leonard! are you beside yourself?"

"Somebody dearer than myself," answered Leonard with a famous burst of sentiment and valor. "Esther, you must be first to know how happy I am" -- but Miss Jaffrey turned away and followed Nelly into the house with stately steps. Nelly had disappeared, and the sister waited for her brother to come in. It seemed as if they could see the indignant eyes of the family portraits through the dark.

"Go to your room, Leonard, I am tired out. I leave you to think what you have been doing in your thoughtlessness. Nelly must leave us at once," said Miss Jaffrey in the same hard voice, and the convicted listener meekly obeyed. There seemed little use in bolting the doors of the old Jaffrey house now that its pride and honor had fallen, but the mistress patiently went her nightly round, and was careful to follow all her time-honored customs of care-taking before she wearily climbed the stairs.

In three rooms that night were three wide-awake and troubled persons. Nelly cried bitterly for a whole half hour at the woeful ending of her new joy. Miss Jaffrey sat in the moonlight, still and pale as if she were made of wood. Mr. Leonard Jaffrey fell asleep long before the first hour of the vigil was past, but was enough alive to the gravity of the occasion not to go to bed. He sat in the study chair by the table; it might have been that the dangerously pendent volume on his bed's canopy could not refrain from letting itself be the instrument of capital punishment.

It seemed very late in the night when the scholar was roused from pleasant dreams by a rap at his door. Before he could fairly open his eyes, Miss Jaffrey entered, carrying the last end of her candle in a tall silver candlestick, and she placed this on the table and stood looking at him, while he rubbed his eyes and tried to remember what was the matter and then to appear heroic. On the whole it was a gratification to find that he was disturbed enough not to go to bed, but his sister relented sufficiently to say that he might as well have been there, it was very foolish to run the risk of getting cold at his age.

"We are only as old as our hearts are," said Leonard, still looking upon himself as the successful lover, but his voice sounded like that of a whimpering boy.

"Be still, Leonard!" cried the over-wrought woman. Her own loveless life cried out suddenly, fired as it was by a piteous jealousy that was hard to bear. She saw her brother at last without the least disguise of sentiment. No hope was there any longer, of professorship, or pulpit; she had abased her pride and starved and forbidden the hopes of her own life for this.

"I thought that we must talk about Nelly as soon as possible," she said presently, in a stumbling, weak way. "I feel as if we have broken the trust of having her here, and John Grant will be free to blame us both" --

"Esther," said the culprit, leaving his chair somewhat stiffly, "I am engaged to marry his daughter. I do not see why you think our loving each other so disgraceful. The Jaffreys" --

"Don't, Leonard!" and Miss Jaffrey steadied herself by the table. "We must put all that by. What right have you to ask that young girl to marry you? What have you to give her? Are you going to let John Grant support you? He is a clearheaded, right-minded man, and you have not a cent, unless I give it you; we have been nearer beggary in our lives than you have ever known. It would not be like you to think what John Grant will say."

"I shall stand before him as an honest man and a gentleman. I wish you would go to bed, Esther, and let things take their course. We are no poorer than we ever have been. I wonder that Nelly loves me, but she does, and she loves you. I have some work, very valuable data and that sort of thing, which I mean to prepare for publication. There may be duties in connection with the academy," murmured Mr. Leonard Jaffrey with some confidence.

"There is the shop," replied his sister, looking gray and old. "I have very few dollars laid aside after all these years. You must go to John Grant's to live," she said savagely, as if she meant it for a taunt. "No doubt he will remember that you are a Jaffrey."

"It would be too far from the post-office," said the placid, literal man, taking a step or two toward the door, which was slowly swinging open, released as if for a ghost's entrance by its worn latch, and then Miss Jaffrey, disheartened and shivering with excitement, left the room without another word. She was powerless with all her clever energy and loyal steadfastness before this purposeless creature of indolent drifting and lifelessness. Ah, well; she had often tortured herself in past years by wondering what would become of him if she died first; his future was secure now, even Betty would take his part and rejoice in the luxury that this marriage would make permanent.

VIII.

The pear-trees opened their blossoms all night, the maples and lilacs and syringas swelled their buds and showed fresh tips of green by morning. There were bluebirds and robins at work in the garden and singing high in the elms all along the Grafton street. It was a terrible ordeal for the three members of the family to meet each other at breakfast time, but high tragedy is impossible by daylight, however suitable it may appear at night. Nelly Grant looked frightened and heavy-eyed and a little sulky; Miss Jaffrey was thin and old, but most appealing, with a gentle stateliness that won the young girl's heart all over again. The lover looked and appeared exactly as usual.

"Nelly," said Esther Jaffrey, and she held out her hand to the girl. "Nelly, I have been very much grieved and worried, but I do not mean to be unkind. You are very young, a great deal younger than my brother and me, and you must not think of -- this any more until your father has heard of it. My brother will talk with him as soon as possible, and you must be reasonable; there are so many things which make me think it would be unwise" -- and then the good woman turned to the breakfast-table, and tried to behave as if nothing had happened. It was not a repast which was afterward remembered as having been cheerful or convivial, but it was brief and things were at least made no worse. Nelly helped Miss Jaffrey wash the china and silver afterward; she noticed curiously for the first time the handsome crest that was engraved on the silver cream-pitcher, and looked up to find her companion's eyes fixed upon her with unwonted coldness. The crest did not mean half so much to Nelly as one might have thought or wished, and was not in the least connected with her simple ambitions. Alas, how Miss Jaffrey's heart was aching! She had never been ashamed before as she was ashamed now. The Jaffreys were to be John Grant's dependents, unless he was sensible enough to cast them off and accuse them indignantly of lack of care for his daughter and her best interests. Alas, alas! If Nelly would only go to school it would be more possible to think what should be done; but it was a long hour from eight to nine, and Leonard would not even go to his study and take himself out of the way. If Miss Jaffrey had understood that the lovers were hoping to have a few words alone together, I do not think that she was in a frame of mind to have granted the opportunity.

There came a loud knock at the front door just as Nelly was coming down-stairs with her school-books. She looked rueful when she saw her father, and was startled into a fear that Miss Jaffrey had already summoned him, and that Lynch-law was to be served upon her love. But the other selectmen of the town were with him, and she waited on the stairs while they solemnly deposited their hats on the straight-backed mahogany chair by the parlor door and disappeared, then she flew out to school without even a greeting to her father, who started to call her back, and then remembered the important business in hand.

"We have come to see your brother on business this morning," said the spokesman, turning to Miss Jaffrey, though the brother was also in the room. "You are acquainted with the fact that the selection of a librarian for the new library built under our supervision, together with that of the committee, rests in our hands. We have said nothing of the time of decision, for fear that outside influence would be brought to bear. We don't feel as if we had any right to pass by such a distinguished lover of learning and a member of our most noted family, and now request Mr. Jaffrey to consider and accept. There will be arduous work in selecting the books and getting the thing going," said the selectman, relaxing from the effort of his previously composed speech, and beginning to grow red in the face and damp as to his skin, "but I can tell you there's money enough to pay the bills, and for clerk-hire too, if he wants it. The regular salary at present, besides expenses, will be a thousand dollars a year."

Miss Jaffrey and her brother looked at each other; he at least was triumphant. "I accept this mark of confidence with profound thanks," said Leonard bowing handsomely to the selectmen. "I shall feel that my long years of study have been in the providence of God a special training for the position."

Miss Jaffrey was dizzy and unnerved; she bade the selectmen good-morning, for they were in haste with morning calls at that season of the year, being busy farmers. The new librarian ushered them out with great politeness and closed the hall-door gently. Then he stopped a moment to reflect, and presently hurried back on tiptoe with a pompous smile. Miss Esther still stood where he had left her.

"I am very glad and proud, brother," she said with effort, and the great man was unexpectedly a little chilled.

"Esther," he answered amiably, as if he had something to forgive her, "I have always had confidence that the time would come when I should be able to repay your kindness. You must be done with the shop now. We" --

"Never!" said the pale old woman, but in spite of this, her heart felt curiously light. At that moment the shop-bell tinkled impatiently, and Miss Jaffrey went in, stately as a princess, to wait upon an early customer.

As was the case with her most famous short story, "A White

Heron," Jewett was unable to sell "A Village Shop" to a

magazine; it first appeared in The King of Folly Island

(1888). If you find errors in this text or items you believe

should be annotated, please contact the site manager.

[ Back ]

Grafton: This village seems based

on Jewett's home of South Berwick, located on a tidal river,

with a respected academy, and a similar history.

[ Back ]

Harvard College: Harvard

University, in Cambridge, MA, is the oldest institution of

higher learning in the United States. The college was founded in

1636 to train young men for the ministry, and this continued to

be an important mission well into the 19th Century.

[ Back ]

Oxford student: Oxford University,

in Oxford, England, dates from the 12th Century.

[ Back ]

in gown and bands: Bands are two

strips of linen hanging from the neck in front as part of a

clerical, legal, or academic dress. Often this dress consists of

a long, full-sleeved gown worn over one's ordinary clothing.

[ Back ]

a Quincy, a Bolyston, a Winthrop,

or a Gardiner: The Quincy family was well-known in

Massachusetts politics. John Quincy, the maternal

great-grandfather of the sixth United States President, John

Quincy Adams (1767-1848), was a prominent member of the

Massachusetts legislature. Zabdiel Boylston (1676-1766) was the

physician who introduced smallpox inoculation to the American

colonies in 1721. After overcoming considerable difficulty and

achieving notable success, Boylston traveled to London in 1724

and was elected to the Royal Society in 1726. John Winthrop

(1588-1649) arrived in Massachusetts with the Puritan pilgrims

and became the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Sylvester Gardiner founded the Gardinerstown Plantation in

Kennebec County in southeastern Maine in 1754. The modern town

of Gardiner, Maine, was the boyhood home of Edwin Arlington

Robinson (1869-1935). (Sources: Britannica Online and Grolier's

Multimedia Encyclopedia)

[ Back ]

what the canny Scotsmen call "a

stickit minister": [Scot.] Stickit minister, a candidate

for the clerical office who fails, disqualified by incompetency

or immorality. (Source: ARTFL Project: Webster Dictionary, 1913;

research Barbara Martens)

[ Back ]

packets and gundalows: A packet

was, originally, a vessel employed by government to convey

dispatches or mail; hence, a vessel employed in conveying

dispatches, mails, passengers, and goods, and having fixed days

of sailing; a mail boat. "Gundalow" is a localization of

"gondola," referring in American usage to a flat-bottomed boat

used for freight.

[ Back ]

The embargo: The Embargo Act

of 1807, sometimes known as Jefferson's Embargo, devastated the

smaller New England ports. Its purpose was to punish England and

France for capturing neutral ships and impressing sailors for

use in their fiercely contested war, but the embargo was a

costly, much resented strategy.

[ Back ]

like Hawthorne's Miss Pyncheon:

See Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables

(1851), especially the opening chapter. This story contains many

echoes of Hawthorne's novel.

[ Back ]

Ship Esther, Brig Marlborough,

Brig Brasenose, Ship Palatine, Ship Patroclus: For one

prominent "Esther," see the book of Esther in the Old Testament.

Esther became a hero when she persuaded her husband, a Persian

king, to rescind an order to massacre her Jewish people.

Brasenose College (founded 1509) is a part of Oxford University.

John Churchill Marlborough (1650-1722) was one of England's

greatest generals, winning several victories over Louis XIV of

France, one of these at Blenheim (1704). Palatine, by the

nineteenth century, would indicate a position of leadership. Britannica

Online says, "Originally the term was applied to the

chamberlains and troops guarding the palace of the Roman

emperor. In Constantine's time . . . . During the early European

Middle Ages the term palatine applied to various officials among

the Germanic peoples." Pactolus was the river in which Midas

purified himself to get rid of his golden curse. (Research

assistance: Gabe Heller).

[ Back ]

that cheerfulness which the

Lord himself loves: "God loveth a cheerful giver." II

Corinthians 9:7.

[ Back ]

the early fathers: of the

Christian church. A Father of the Church, according to Britannica

Online is "any of the great bishops and other eminent

Christian teachers of the early centuries whose writings

remained as a court of appeal for their successors, especially

in reference to controverted points of faith or practice."

Perhaps among the better known of these are the saints: Ambrose,

Ignatius, and Jerome.

[ Back ]

Franklin stove: type of

wood-burning stove, invented by Benjamin Franklin (c. 1740). The

Franklin stove burned wood on a grate and had sliding doors that

could be used to control the draft (flow of air) through it.

Because the stove was relatively small, it could be installed in

a large fireplace or used free-standing in the middle of a room

by connecting it to a flue. Its design influenced the potbellied

stove. (Source: Britannica Online; research, Barbara

Martens)

[ Back ]

rock-maple wood: Also known as the

sugar maple or hard maple. A large tree in the maple family

native to eastern North America and widely grown as an

ornamental and shade tree. (Source: Britannica Online;

research, Barbara Martens)

[ Back ]

pippin apples: An apple from a tree

raised from the seed and not grafted; a seedling apple, but this

name also has been given to several different kinds of apples.

(Source: ARTFL Project: Webster Dictionary, 1913)

[ Back ]

mental philosophy: relating to the

mind as an object of study. See for example, T. C. Upham, Elements

of Mental Philosophy (1860). (Source: Oxford English

Dictionary)

[ Back ]

Baconian philosophy: Refers to

the empiricism of Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Bacon offered a

program for learning and for reforming the scientific method in

the Advancement

of Learning (1605) and other works. (Source: Britannica

Online)

[ Back ]

silk Geneva gown: A black,

large, loose-sleeved academic gown, so called because of its use

by Calvinist clergy of Geneva, Switzerland.

[ Back ]

Washington and Mount Vernon that

Mecca: Washington, D.C., the United States capital; Mount

Vernon along the Potomac River in Virginia, south of Washington,

D.C., the home of George Washington, is a place of pilgrimage

for Americans as Mecca in Saudi Arabia is for Muslims.

[ Back ]

the great exhibition day:

a school exercise at the end of the academic year, when students

exhibit their accomplishments.

[ Back ]

the box: a blooming box

hedge, native to the Mediterranean region. The wood is useful

for carving. The tree is grown in many parts of the world as a

border, hedge, or an ornamental shaped bush. (Source: Britannica

Online)

the box: a blooming box

hedge, native to the Mediterranean region. The wood is useful

for carving. The tree is grown in many parts of the world as a

border, hedge, or an ornamental shaped bush. (Source: Britannica

Online)

[ Back ]

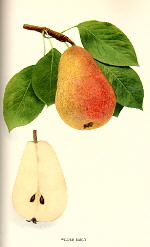

St. Michael's pear tree: U.

P. Hedrick, in The Pears of New York (Albany: J. B.

Lyon, 1921), says that the White Doyenné pear was called the St.

Michael's pear in the Boston area in the 19th century, when this

variety was considered one of the best for eating, though

difficult to cultivate. As pears became increasingly a

commercial product, this variety disappeared along with many

others of the more than 120 that Hedrick describes as having

grown in New York and the Northeastern United States in the

nineteenth century. The illustration is from Hedrick.

[ Back ]

syringa thicket: Syringa (bot.

genus), any of about 30 species of fragrant and beautiful

northern spring-flowering garden shrubs and small trees. May

refer to lilacs or to mock orange. (Source: Britannica

Online; research, Barbara Martens)

[ Back ]

Lynch-law: Lynching is a "form of

mob violence in which a mob executes a presumed offender, often

also torturing him and mutilating his body, without trial, under

the pretense of administering justice. The term "lynch law"