Main Contents & Search

A Native of Winby

The Scribner's Text

.

Sarah Orne Jewett

I.

The early winter twilight was falling over the town of Kenmare; a heavy open carriage with some belated travelers bounced and rattled along the smooth highway, hurrying toward the inn and a night's lodging. Two slender young figures drew back together into the leafless hedge by the roadside and stood there, whispering and keeping fast hold of hands after the simple fashion of children and lovers. There was an empty bird's nest close beside them, and they looked at that, and after they had watched the carriage a moment, and even laughed because Dinny Killoren, the driver, had recognized their presence by a loud snap of his whip, they still loitered. The girl turned away from her lover, who only looked at her, and felt the soft lining of the nest with the fingers of her left hand. Johnny Morris's handsome young face looked pinched and sad in the gray dampness of the dusk.

"The poor tidy cr'atures!" said Nora Connelly. "Look now at their little house, Johnny, how nate it is, and they gone from it. I mind the birds singing in the hedge one day last summer, and I walking by in the road."

"Wisha, 'tis our own tidy house I'm thinking of," said Johnny reproachfully; "I've long dramed of it, and now whatever will I do and you gone away to Ameriky? Faix, it's too hard for us, Norry dear; we'll get no luck from your goin'; 'twas the Lord mint us for aich other!"

"I'm safe to come back, darling," said Nora, troubled by her lover's lamentations. "'Tis for the love of you I'm going, sure, Johnny dear! I suppose 'tis yourself won't want me then aither, when I come back; sure they says folks dries all up there, and gets brown and small wit' the heat that's in it. Promise now that you'll say nothing sharp, so long as I'm fine an' rich coming home!"

"Don't break me heart, Nora, wit' your wild talk; who else but yourself would be joking, and our hearts breaking wit' parting, and this our last walk together," mourned the young man. "Come, darling, we must be going on.'Tis a good way yet through the town, an' your aunt's ready to have my life now for not sinding you back at t'ree o'clock."

"Let her wait!" said Nora scornfully. "I'll be free of her, then, this time to-morrow. 'Tis herself'll be keenin' after me as if 'twas wakin' me she was, and the cold heart of stone that's inside her and no tears to her eyes. They might be glass buttons in her old head, they might then! I'd love you to the last day I lived, John Morris, if 'twas only to have the joke on her;" and Nora's eyes sparkled with fun. "I'd spite her if I could, the old crow! Sorra a bit of lave-takin' have I got from her yet, but to say I must sind home my passage-money inside the first month I'm out. Oh, but, Johnny, I'll be so lonesome there; 'tis a cold home I had since me mother died, but God help me when I'm far from it!" The girl and her lover were both crying now; Johnny kissed her and put his arms tenderly about her, there where they stood alone by the roadside; both knew that the dreaded hour of parting had come.

Presently, as if moved by the stern hand of fate rather than by their own will, they walked away along the road, still weeping. They came into the town, where lights were bright in the houses. There was the usual cheerful racket about the inn. The Lansdowne Arms seemed to be unusually populous and merry for a winter night. Somebody called to Johnny Morris from a doorway, but he did not answer. Close by were the ruins of the old abbey, and he drew Nora with him between the two stones which made a narrow entrance-way to the grounds. It was dreary enough there among the wintry shadows, the solemn shapes of the crumbling ruin, and the rustling trees.

"Tell me now once more that you love me, darling," sobbed the poor lad; "you're goin' away from me, Nora, an' 'tis you'll find it aisy to forget. Everything you lave will be speakin' to me of you. Oh, Nora, Nora! howiver will I lave you go to Ameriky! I was no man at all, or why didn't I forbid it? 'Tis only I was too poor to keep you back, God help me! O Dea! O Dea!"

"Be quiet now;" said Nora. "I'll not forget you. I'll save all my money till I'll come back to you. We're young, dear lad, sure; kiss me now an' say good-by, my fine gay lad, and then walk home quiet wit' me through the town. I call the holy saints to hear me that I won't forget."

And so they kissed and parted, and

walked home quiet through the town as Nora had desired. She

stopped here and there for a parting word with a friend, and

there was even a sense of dignity and consequence in the poor

child's simple heart because she was going to set forth on her

great journey the next morning, while others would ignobly

remain in Kenmare. Thank God, she had no father and mother to

undergo the pain of seeing her disappear forever from their

eyes. The poor heart-broken Irish folk who let their young sons

and daughters go away from them to America, -- which of us has

stopped half long enough to think of their sorrows and to pity

them? What must it be to see the little companies set forth on

their way to the sea, knowing that they will return no more? The

fever for emigration is a heart-rending sort of epidemic, and

the boys and girls who dream of riches and pleasure until they

are impatient of their homes in poor, beautiful Ireland! alas,

they sail away on the crowded ships to find hard work and hard

fare, and know their mistakes about finding a fairy-land too

late, too late! And Nora Connelly's aunt had hated Johnny

Morris, and laid this scheme for separating them, under cover of

the furtherance of Nora's welfare. They had been lovers from

their childhood, and Johnny's mother, from whom Nora had just

parted on that last sad evening, was a sickly woman and poor as

poverty. Johnny was like son and daughter both, he could never

leave her while she lived; they had needed all of Nora's

cheerfulness and love, and now they were going to lose her,

perhaps forever. Everybody knew how few come back from America;

no wonder that these Irish hearts were sad with parting.

On the morrow there was little time

for leave-takings. Some people tried to make it a day of jokes

and festivities when such parties of emigrants left the

country-side, but there was always too much sadness underneath

the laughter; and the chilly rain fell that day as if Ireland

herself wept for her

wandering children, -- poor Ireland, who gives her best to

the great busy countries over seas, and longs for the time when

she can be rich and busy herself, and keep the young people at

home and happy in field and town. What does the foreign money

cost that comes back to the cottage households broken as if by

death? What does it cost to the aching hearts of fathers and

mothers, to the homesick lads and girls in America, with the

cold Atlantic between them and home?

The winter day was clear and cold, with a hint of coming spring in the blue sky. As you came up Barry Street, the main thoroughfare of a thriving American town, you could not help noticing the thick elm branches overhead, and the long rows of country horses and sleighs before the stores, and a general look of comfortably mingled country and city life.

The high-storied offices and warehouses came to an end just where the hill began to rise, and on the slope, to the left, was a terraced garden planted thick with fruit-trees and flowering shrubbery. Above this stood a large, old-fashioned white house close to the street. At first sight one was pleased with its look of comfort and provincial elegance, but as you approached, the whole lower story seemed unused. If you glanced up at a window of the second story, you were likely to see an elderly gentleman looking out, pale and unhappy, as if invalidism and its enforced idleness were peculiarly hard for him to bear. Sometimes you might catch sight of the edge of a newspaper, but there was never a book in his hand, there was never a child's face looking out to companion the old man. People always spoke of poor old Captain Balfour nowadays, but only a few months before, he had been the leading business man of the city, absorbed in a dozen different enterprises. A widower and childless, he felt himself to be alone indeed in this time of illness and despondency. Early in life he had followed the sea, from choice, not necessity, but for many years he had been master of the old house and garden on Barry Street, his inherited home. People always spoke of him with deference and respect, they pitied him now in his rich and pitiful old age. In the early autumn a stroke of paralysis had dulled and disabled him, and its effect was more and more puzzling, and irritating beside to the captain's pride.

He more and more insisted upon charging his long captivity and uncomfortable condition at the doors of his medical advisers and the household. At first, in dark and gloomy weather, or in days of unusual depression, a running fire of comments was kept up toward those who treated him like a child, and who made an apothecary's shop of his stomach, and kept him upon such incomprehensible diet. A slice of salt beef and a captain's biscuit were indignantly demanded at these times, but it was touching to observe that the person in actual attendance was always treated with extreme consideration or even humble gratitude, while the offenders were always absent. "They" were guilty of all the wrongs and kept the captain miserable; they were impersonal foes of his peace; there never was anything but a kind word for Mrs. Nash, the housekeeper, or Reilly, the faithful attendant; there never were any personal rebukes administered to the cook; and as for the doctor, Captain Balfour treated him as one gentleman should treat another.

Until early in January, when once in a while even the hitherto respected Mrs. Nash was directly accused of a total lack of judgment, and James Reilly could not do or say anything to suit, and the lives of these honest persons became nearly unbearable; the maid under Mrs. Nash's charge (for the household had always been kept up exactly as in Mrs. Balfour's day) could not be expected to consider the captain's condition and her own responsibilities as his older and deeply attached companions could, and, tired of the dullness and idleness of the old house, fell to that state where dismissal was inevitable. Then neither Mrs. Nash nor Reilly knew what to do next; they were not as young as they had been, and, to use their own words, minded the stairs. At last Reilly, a sensible man, proposed a change in the order of housekeeping. The captain might never come downstairs any more; they could shut up the dining-room and the parlors, and make their daily work much lighter.

"An' I won't say that I haven't got word for you of a tidy little girl," said Reilly, beseechingly. "She's a relation to my cousins the Donahues, and as busy as a sparrow. She'll work beside you an' the cook like your own shild, she will that, Mrs. Nash, and is a light-hearted shild the day through. She's just over too, the little greenhorn!"

"Perhaps she'll be just what we want, Reilly," agreed the housekeeper, after reflection. "Send her up to see me this very evening, if you're going where she is."

So the very next day into the desolate

old house came young Nora Connelly, a true child of the old

country, with a laughing gray eye and a smooth girlish cheek,

and a pretty touch of gold at the edge of the fair brown hair

about her forehead. It was a serious little face, not beautiful,

except in its delightful girlishness. She was a friendly, kindly

little creature, fond of her simple pleasures, and willing to

work hard the day through. The great house itself was a

treasure-house of new experience, and she felt her position in

the captain's family to be a valued promotion.

One morning, life looked very dark to the master. Everything had been going wrong since breakfast, and the captain rang for Reilly when he had just gone out, and Mrs. Nash was busy with a messenger.

"Go up, will you, Nora?" she said anxiously, "and say that I'll be there in a minute. Reilly's just left him."

And Nora sped away, nothing loath; she had never taken a satisfactory look at the master, and this was the fourth day since she had come to the house.

She opened the door and saw a handsome, fretful, tired old gentleman, whose newspaper had slipped from his hand and gone out of reach. She hurried to pick it up, without being told.

"Who are you?" inquired the captain, looking at her with considerable interest.

"Nora Connelly, sir," said the girl in a delicious Irish voice.

"I'm your new maid, sir, since Winsday. I feel very sorry for your bein' ill, sir."

"There's nothing the matter with me:" growled the captain unexpectedly.

"Wisha, sir, I'm glad of that!" said Nora, with a wag of her head like a bird, and a light in her eye. "Mrs. Nash'll be here at once, sir, for your ordhers. She is daling wit' a boy below in the hall. You are looking fine an' comfortable the day, sir."

"I never was so uncomfortable in my life," said the captain. "You can open that window."

"And it snowing fast, sir? You'll let out all the fine heat; heat's very dear now and cold is cheap, so it is, with poor folks. 'Tis a great pity you've no turfs now to keep your fire in for you. 'Tis very strange there do be no turf in this foine country;" and she looked at the captain with a winning smile. The captain smiled back again in spite of himself.

Nora stood looking out of the window; she seemed to be thinking of herself instead of the invalid.

"What did you say your name was?" asked the old gentleman, a moment later, frowning his eyebrows at her like pieces of artillery.

"Plase, sir, I'm Nora Connelly, from the outside o' Kenmare." She made him the least bit of a courtesy as if a sudden wind had bent her like a long-stemmed flower.

"How came you here?" His mouth straightened into a smile as he spoke, in spite of a determination to be severe.

"I'm but two weeks over, sir. I come over to me cousins, the Donahues, seeking me fortune. I'd like Ameriky, 'tis a fine place, sir, but I'm very homesick intirely. I'm as fast to be going back as I was to be coming away;" and she gave a soft sigh and turned away to brush the hearth.

"Well, you must be a good girl," said the captain, with great propriety, after a pause.

"'Deed, sir, I am that," responded Nora sincerely. "No one had a word to fling afther me and I coming away, but crying afther me. Nobody'll tell anything to my shame when my name'll be spoke at home. My mother brought me up well, God save her, she did, then!"

This unaffected report of her own good reputation was pleasing to Nora's employer; the sight of Nora's simple, pleasant Irish face and the freshness of her youth was the most delightful thing that had happened in many a dreary day. He felt in his waistcoat pocket with sudden impulse, sure of finding a bit of money there with which Nora Connelly might buy herself a ribbon. He was strongly inclined toward making her feel at home in the old house which had grown to be such a prison to himself. But there was no money in the pocket, as there always used to be when he was well. He had not needed any before in a long time. He began to fret about this, and to wonder what they had done with his pocket-book; it was ignominious to be treated like a school-boy. While he brooded over his wrongs, Nora heard Mrs. Nash's hurrying footsteps in the hall, but as she slipped away it was plain that she had found time enough to bestow her entire sympathy, and even affection, upon the captain in this brief interview.

"He's dull, poor gentleman, -- he's

very sad all day by himself, and so pleasant spoken, the

cr'ature!" she said to herself indignantly, as she went running

down the stairs.

It was not long before, to everybody's surprise, Captain Balfour gained strength, and began to feel so much better that Nora was often posted in the room or the hall close by to run his frequent errands and pick up his newspapers as they fell. This gave Mrs. Nash and Reilly a chance to look after their other business affairs, and to take their ease after so long a season of close attendance. The captain had a gruff way of asking, "Where's that little girl?" as if he only wished to see her to scold roundly; and Nora was always ready to come with her sewing or any bit of housework that could be carried, and to entertain her master by the hour. The more irritable his temper, the more unconscious and merry she always seemed.

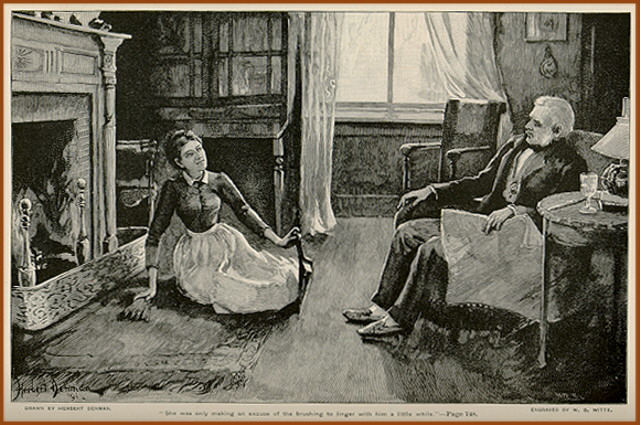

"I was down last night wit' me cousins, so I was," she informed him one morning, while she brushed up the floor about the fireplace on her hands and knees. "You'd ought to see her little shild, sir; indade she's the darling cr'ature. I never saw any one so crabbed and smart for the size of her. She ain't the height of a bee's knee, sir!"

"Who isn't?" inquired the captain absently, attracted for the moment by the pleasing simile.

"Me cousin's little shild, sir," answered Nora appealingly, with a fear that she had failed in her choice of a subject. "'Tis no more than the heighth of a bee's knee she is, the colleen, and has every talk to you like a little grandmother, -- the big words of her haves to come sideways out of her mouth. I'd like it well if her mother would dress her up prertty, and I'd go fetch her for you to see."

The captain made an expressive sound of disdain, and Nora brushed away at the rug in silence. He looked out of the window and drummed on the arm of his chair. It was a very uncomfortable morning. There was a noise in the street, and Nora pricked up her ears with her head alert like a young hare, stood up on her knees, and listened.

"I'll warrant it's me heart's darling tooting at the fife," she exclaimed.

"Nothing but a parcel of boys," grumbled the captain.

"Faix it's he, then, the dacint lad!" said Nora, by this time close to the other front window. "Look at him now, sir, goin' by! He's alther-b'y in the church, and a lovely voice in him. Me cousins is going to have him learn music. That's 'The girl I left behind me,' he's got in the old fife now."

"Hard to tell what it is," growled the captain. "Anything for a racket, I dare say."

"Faix, sir, I was thinking meself the tune come out of it tail first," agreed Nora with ready sympathy. "He's the big brother to the little sisther I told you of just now. 'Twas Dan Sullivan gave Johnny the old fife; himself used to play it in a company. There's a kay or two gone, I'm misthrusting; anyway there's teeth gone in the tune."

Nora was again brushing the floor industriously. The captain was listless and miserable; the silence vexed him even more than the harmless prattle.

"I used to play the flute pretty well myself when I was a young man," he said pleasantly, after a while.

"I'd like well to hear you, then, sir," said Nora enthusiastically. She was only making an excuse of the brushing to linger with him a little while. "Oh, but your honor would have liked to hear me mother sing. God give her rest, but she had the lovely voice for you! They'd be sinding for her from three towns away to sing with the fiddle for weddings and dances. If you'd hear her sing the 'Pride of Glencoe' 'twould take the heart out of you, it would indade."

She was only making an excuse of the brushing to linger with him a little while.

"My wife was a most beautiful singer when she was young. I like to hear a pretty voice," said the captain sadly.

"'Twas me dear mother had it, then," answered Nora. "I do be often minding her singing when I'm falling asleep. I hear her voice very plain sometimes. My mother was from the north, sir, and she had tunes that didn't be known to the folks about Kenmare. 'Inniskillen Dragoon' was one of the best liked, and it went lovely with the wheel when she'd be spinning. Everybody'd be calling for her to sing that tune. Strangers would come and ask her for a song that were passing through the town. There was great talk always of me mother's singing; they'd know of her for twinty miles round. Whin I see the fire gone down in red coals like this, like our turf at home, and it does be growing dark, I remimber well 'twas such times she'd sing like a bird for us, being through her long day's work, an' all of us round the fire kaping warm if we could, a winter night. Oh, but she'd sing then like a lark in the fields, God rest her!"

Nora brushed away a tear and blessed herself. "You'd like well to hear me mother sing, sir, I'm telling you God's truth," she said simply. And the old captain watched her and smiled, as if he were willing to hear more.

"Folks would pay her well, too. They'd all be afraid she'd stop when she'd once begin. There was nobody but herself could sing with the fiddle. I mind she came home one morning when she'd been sint for to a great wedding, -- 'twas a man's only daughter that owned his own land. And me mother came home to us wit' a collection of twilve and eight-pince tied up in her best apron corner. We'd as good as a wedding ourselves out of it too; 'twas she had the spinding hand, the cr'ature; and we had a roast goose that same night and asked frinds to it. Folks don't have the good fun here they has in the old counthry, sir, so they don't."

"There used to be good times here," said the poor old captain.

"I'm thinking 'twould be a dale the better if you wint and stayed for a while over there," urged the girl affectionately. "It'll soon be comin' green and illigant while it's winther here still; the gorse'll be blooming, sir, and the little daisies thick under your two feet, and you'd be sitting out in the warm rain and sun, and feeling the good of the ground. If you'd go to Glengariff, I think you'd be soon well, I do, then, Captain Balfour, your honor, sir."

"I'm too old, Nora," replied the captain dismally but not without interest.

"Sure there ain't a boy in the town that has the spark in his eye like yourself, sir," responded Nora, with encouraging heartiness. "I'd break away from these sober old folks and the docthers and all, and take ship, and you'd be soon over the say, and live like a lord in the first cabin; and you'd land aisy on the tinder in the cove o' Cork, and slape that night in the city, and go next day to the Eccles Hotel in Glengariff. Oh, wisha, the fine place it is wit' the say forninst the garden wall. You'd get a swim in the clane salt wather, and be as light as a bird. Sure I wouldn't be tased wit' so much docthoring and advising, and you none the betther wit' it."

"Why couldn't I have a swim in the sea here?" inquired the captain indulgently.

"Sure, it wouldn't be the same at all," responded Nora, with contempt. "'Tis the sayshore of the old country will do you the most good. The say is very salt entirely by Glengariff; the bay runs up to it, and you'd get a strong boatman would row you up and down, and you'd walk in the green lanes, and the folks in the houses would give you good-day; and if you'd be afther givin' old Mother Casey a trippence, she'd down on her two little knees and pray for your honor till you'd be running home like a light-horseman."

The old man laughed heartily for the first time that day. "I used to be the fastest runner of any lad in school," he said, with pride.

"Sure you might thry it again, wit' Mrs. Casey's kind help, sir," insisted the girl. "Now go to Glengariff this next month o' May, sir, do!"

"Perhaps I will," said the captain decidedly. "I'm not going to keep up this sort of thing much longer, I can tell them that! If they can't do me any good, they may say so, and I'll steer my own course. That's a good idea about the salt water."

The old man fell into a pleasant sleep, with a contented smile on his face. The fire flickered and snapped, and Nora sat still looking into it; her thoughts were far away. Perhaps her unkind aunt would find means to stop the letters between Johnny Morris and herself. Oh, if her mother were only alive, if the scattered household were once more together! It would be a long time at this rate, before she could go back to Johnny with a hundred pounds.

The fire settled itself together and sent up a bright blaze. The old man opened his eyes and looked bewildered; she stepped quickly to his side. "You'll be askin' for Mr. Reilly?" she said.

"No, no," responded the captain firmly. "What was the name of that place you were talking about?"

"Whiddy Island, sir, where me father was born?" Nora's thoughts had wandered far and wide; she was thinking that she had heard that land was cheap on Whiddy and the fishing fine. She and Johnny had often thought they might do better than in Kenmare.

"No, no," said the captain again, sternly.

"Oh, Glengariff," she exclaimed. "Yes, sir, we were talking" --

"That's it," responded the captain complacently. "I should like to know something more about the place."

"I was never in it but twice," exclaimed Nora, "but 'twas lovely there intirely. My father got work at fishin', and 'twas one summer we left Kenmare and went to a place, Baltimore was the name, beyond Glengariff itself, toward the illigant town of Bantry, sir. I saw Bantry sir, when I was young. We were all alive and together then, my father and mother and all of us; the old shebeen we lived in looked like the skull of a house, it was so old, and the roof falling in on us, but thank God, we were happy in it. Oh, Ireland's the lovely counthry, sir."

"No bad people at all there?" asked the captain, looking at her kindly.

"Oh, sir, there are then," said the little maid regretfully. "I have sins upon my own soul, truth I have, sir. Thesin of staling was my black shame when I was growing up, then."

"What did you ever steal, child?" asked the captain.

"Mostly eggs, sir," said Nora humbly.

"I dare say you were hungry," said the old man, taking up his newspaper and pretending to frown at the shipping-list.

"Oh, no, captain, 'twas not that always. I used to follow an old spickled hen of my mother's and wait for the egg. I'd track her within the furze, and when I'd be two days gettin' two eggs I'd run wit' 'em to sell 'em, and 'twas to buy things to sew for me doll I'd spind the money. I'd ought to make confission for it now, too. I'm ashamed, thinkin' of it. And the spickled hen was one that laid very large white eggs intirely, and whiles my poor mother would be missing them, and thinking the old hen was no good and had best be killed, the honest cr'ature, and go to market that way when poulthry was dear. I'd like one of her eggs now to boil it myself for you, sir; t'would be fine atin' for you coming right in from some place under the green bushes. I think that hen long's dead, I didn't see her a long while before I was lavin'. A woman called Johanna Spillane bought her from my aunt when my mother was dead. She was a very honest, good hen; a top-knot hen, sir."

"I dare say," said the captain, looking at his newspaper; he did not know why the simple chatter touched and pleased him so. He shrugged his shoulders and moved about in his easy-chair, frowned still more at the shipping-list, and so got the better of his emotion.

"I see that the old brig Miranda has gone ashore on the Florida Keys," he said, as if speaking to a large audience of retired shipmasters. "Stove her bows, rigging cut loose and washed overboard; total wreck. I suppose you never saw a wreck?" He turned and regarded Nora affectionately.

"I did, sir, then," said Nora Connelly flushing with satisfaction. "We got news of it one morning early, and all trooped to the shore, every grown person and child in the place, laving out Mother Dolan, the ould lady that had no use of her two legs; and all the women, me mother and all, took their babies to her and left them, and she entreatin' -- you'd hear the bawls of her a mile away -- that some of the folks would take her wit' 'em on their backs to see what would she get wit' the rest; but we left her screechin' wit' all the poor shilder, and I was there with the first, and the sun coming up, and the ship breaking up fine out a little way in the rocks. 'Twas loaded with sweet oranges she was, and they all comin' ashore like yellow ducklings in the high wather. I got me fill for once, I did, indeed."

"Dear, dear," said the captain. "Did the crew get ashore?"

"Well, I belave not, sir, but I couldn't rightly say. I was small, and I took no notice. I mind there were strangers round that day, but sailors or the nixt parish was one to me then. The tide was going out soon, and then we swarmed aboard, and wisha, the old ship tipped up wit' us in it, and I thought I was killed. 'Twas a foine vessel, all gilded round the cabin walls, and I thought in vain 'twould be one like her comin' to Ameriky. There was wines aboard, too, and all the men got their fill. Mesilf was gatherin' me little petticoat full of oranges that bobbed in the wather in the downside of the deck. Wisha, sir, the min were pushin' me and the other shilder into the wather; they were very soon tight, sir, and my own father was wit' 'em, God rest his soul! and his cheeks as red as two roses. Some busybody caught him ashore and took him to the magistrate, -- that was the squire of our place, sir, and an illigant gentleman. The bliguards was holdin' my father, and I running along, screechin' for fear he'd be goin' to jail on me. The old squire began to laugh, poor man, when he saw who it was, and says he, 'Is it yoursilf, Davy?' and says my father, 'It's mesilf, God save your honor, very tight intirely and feelin' as foine as any lord in Ireland. Lave me go, and I'll soon slape it off under the next furze-bush that'll stop still long enough for me by the roadside,' says he. The squire says, 'Lave him go, boys, 'twas from his ating the oranges!' says he, and the folks give a great laugh all round. He was doin' no harrum, the poor man! I run away again to the say then; I forget was there any more happened that day."

"She must have been a fruiter from the Mediterranean. I can't think what she was doing up there on the west coast, out of her bearings," said the captain.

"Faix, sir, I couldn't tell you where

she was from, if it's the ship you mane; but she wint no further

than our parish and the Black Rocks. I heard tell of plinty

other foine wrecks, but I was to that mesilf."

III.

The lengthening days of late winter went slowly by, and at last it was spring, and the windows were left open all day in the captain's room. The household had accepted the fact that nobody pleased the invalid as Nora did, and there was no feeling of jealousy; it was impossible not to be grateful to any one who could invariably spread the oil of sympathy and kindness over such troubled waters. James Reilly and Mrs. Nash often agreed upon the fact that the captain kept all the will he ever had, but little of the good judgment. Yet, in spite of this they took it upon them to argue with him upon every mistaken point. Nora alone had the art of giving a wide berth to dangerous subjects of conversation, and she could twist almost every sort of persistence or aggravation into a clever joke. She had grown very fond of the lonely old man; the instinct toward motherliness in her simple heart was always ready to shelter him from his fancied wrongs, and to quiet him in the darkest hours of fretfulness and pain.

Young Nora Connelly's face had grown thin during the long winter, and she lost the pretty color from her cheeks as spring came on. She was used to the mild air of Ireland, and to an out-of-door life, and she could not feel like herself in the close rooms of Captain Balfour's house on Barry Street. By the time that the first daffodils were in bloom on the south terrace, she longed inexpressibly for the open air, and used to disappear from even the captain's sight into the garden, where at times she took her turn with the gardeners at spading up the rich soil, and worked with a zeal which put to shame their languid efforts. Something troubled the girl, however; she looked older and less happy; sometimes it was very plain to see that she had been crying.

One morning, when she had been delayed unusually with her downstairs work, the captain grew so impatient that he sent Reilly away to find her. Nora quickly set down a silver candlestick, and wiped her powdery hands upon her apron as she ran upstairs. The captain was standing in the middle of the floor, scowling like a pirate in a picture-book, and even when Nora came in, he did not smile. "I'm going out to take a walk," he said angrily.

"Come on, then, sir," said Nora. "I'll run for your coat and hat, if you'll tell me where" --

"Pooh, pooh, child," -- the pacified captain was smiling broadly. "I only want to take a couple of turns here in the hall. You forget how long I've been house-bound. I'm a good deal better; I'll have that meddling Reilly know it, too; and I won't be told what I may do and what I may not."

"'Tis thrue for you, sir," said Nora amiably. "Steady yourself with my arrum, now, and we'll go to the far end of the hall and back again. 'Twas the docther himself said a while ago that ye'd ought to thry walking more, and 'twas your honor was like to have the life of him. You're a very conthrairy gentleman, if I may be so bold!"

The captain laughed, but the business of dragging his poor heavy foot was more serious than he had expected, in spite of all his brave determination. Nora did her best to beguile him from too much consciousness of his feebleness and disappointment.

"Sure if you'd see ould Mother Killahan come hobbling into church, you'd think yourself as good as a greyhound," she said presently, while the master rested in one of the chairs at the hall's end. "She's very old intirely. I saw her myself asleep at her beads this morning, but she do be very steady on her two knees, and whiles she prays and says a bead or two, and whiles she gets a bit of sleep, the poor cr'ature. She does be staying in the church a dale this cold weather, and Father Dunn is very aisy with her. She makes the stations every morning of the year, so she does, and one day she come t'rough the deep snow in a great storm there was, and she fell down with weakness on the church steps; and they told Father Dunn, and said how would they get her home, and he come running himself, scolding all the way, and took her up in his arrums, and wint back with her to his own house. You'd thought she was his own mother, sir. 'She's one of God's poor,' says he, with the tears in his eyes. Oh, captain, sir! I wish it was Father Dunn was praste to you, I do then! I'm thinking he'd know what prayers would be right for you; and himself was born in the country forninst Glengariff, and would tell you how foine it was for your stringth. If you'd get better, sir, and we'd meet him on the street, we'd be afther asking his riverence."

The captain made no answer; he was tired and spent, and sank into his disdained easy-chair, grateful for its comfortable support. The mention of possible help for his feeble frame from any source clung to his erratic memory, and after a few days one of the thoughts that haunted his mind was that Father Dunn, a kind-faced, elderly man, might be of use in this great emergency. To everybody's surprise, his bodily strength seemed to be slowly returning as the spring days went by but there was oftener and oftener an appealing, childish look in his face, -- the firm lines of it were blurred, even while there was a steady renewing of his shattered forces. At last he was able to drive down the busy street one day, with Reilly, in his familiar chaise. The captain's old friends gathered to welcome him, and he responded to their salutations with dignity and evident pleasure; but once or twice, when some one congratulated him upon certain successful matters of business which he had planned before his illness, there was only a troubled look of dullness and almost pain for answer.

One day, Nora Connelly stole out into the garden in the afternoon, and sat there idly under an old peach-tree. The green fruit showed itself thick all along the slender boughs. Nora had been crying already, and now she looked up through the green leaves at the far blue sky, and then began to cry again. She was sadly homesick, poor child! She longed for her lover, whom she feared now never to see. Like a picture she recalled the familiar little group of thatched houses at home, with their white walls and the narrow green lanes between; she saw the pink daisies underfoot, and the golden gorse climbing the hill till it stood against the white clouds. She remembered the figures of the blue-cloaked women who went and came, the barefooted, merry children, and the dabbling ducks; then she fell to thinking lovingly of her last walk with Johnny Morris, the empty bird's nest, and all their hopes and promises the night before she left home. She had been willful in yielding to her aunt's plans; she knew that Johnny feared her faithlessness, but it was all for love of him that she had left him. She knew how poor they were at home. She had faithfully sent a pound a month to her aunt, and though she had had angry appeals for more, the other pound that she could spare, leaving but little for herself, had been sent in secret to Johnny's mother. She always dreaded the day when her avaricious aunt should find this out and empty all the vials of her wrath of covetousness. Nora, to use her own expression, was as much in dread of this aunt as if the sea were a dry ditch. Alas! she was still the same poor Nora Connelly, though rich and busy America stretched eastward and westward from where she made her new home. It was only by keeping her pounds in her pocket that she could gather enough to be of real and permanent use to those she loved; and yet their every-day woes, real or fictitious, stole the pounds from her one by one.

So she sat crying under the peach-tree until the pale old captain came by in the box-bordered walk, with scuffling, unsteady steps. He saw Nora and stopped, leaning on his cane.

"Come, come, Nora!" he said anxiously. "What's the matter, my girl?"

Nora looked up at him and smiled instantly. It was as if the warm Irish sunshine had broken out in the middle of a May shower. A long spray of purple foxglove grew at her feet, and the captain glanced down at it. The sight of it was almost more than she could bear, this flower that grew in the hedgerows at home. She felt as if the flower were exiled like herself and trying to grow in a strange country

"Don't touch it, sir," she faltered, as the captain moved it with his cane; "'tis very bad luck to meddle with that: they say yourself will be meddled with by the fairies. Fairy Fingers is the name of that flower; we were niver left pick it. Oh, but it minds me of home!"

"What's the matter with you to-day?" asked the captain.

"I've been feeling very sad, sir; I can't help it, either, thinkin' o' me home I've left and me dear lad that I'll see no more. I was wrong to lave him, I was indeed."

"What lad?" asked Captain Balfour suspiciously, "I'll have no nonsense nor lads about my place. You're too young" -- He looked sharply at the tearful young face. "Mrs. Nash can't spare you, either," he added humbly, in a different tone.

"Faix, sir, it's at home he is, in the old counthry, without me; he'll niver throuble ye, me poor Johnny," Nora explained sadly enough. She had risen with proper courtesy, and was standing by the old man; now she ventured to take hold of his arm. He looked flushed and eager, and she forgot herself in the instinct to take care of him.

"Where do you be going so fast?" she asked with a little laugh. "I'm afther believing 'tis running away you are."

The captain regarded her solemnly; then he laughed, too. "Come with me," he said. "I'm going to make a call."

"Where would it be?" demanded the girl, with less than her usual deference.

"Come, come! I want to be off," insisted the old gentleman. "We'll go out of this little gate in the fence. I've got to see your Father Dunn on a matter of business," he said, as if he had no idea of accepting any remonstrance.

Nora knew that the doctor and all the elder members of the household approved of her master's amusing himself and taking all the exercise he could. She herself approved his present intentions entirely; it was not for her to battle with the head of the house, at any rate, so she dutifully and with great interest and anxiety set forth beside him down the path, on the alert for any falterings or missteps.

They went out at the gate in the high fence; the master remembered where to find the key, and he seemed in excellent spirits. The side street led them down the hill to Father Dunn's house, but when they reached it the poor captain was tired out. Nora began to be frightened, as she stole a look at him. She had forgotten, in the pride of her own youthful strength, that it would be such a long walk for him. She was anxious about the interview with Father Dunn; she had no idea how to account for their presence, but she had small opinion of the merits and ability of the captain's own parish minister, and felt confident of the good result, in some way, of the visit. Presently the priest's quick step was heard in the passage; Nora rose dutifully as he came in, but was only noticed by a kindly glance. The old captain tried to rise, too, but could not, and Father Dunn and he greeted each other with evident regard and respect. Father Dunn sat down with a questioning look; he was a busy man with a great parish, and almost every one of his visitors came to him with an important errand.

The room was stiff-looking and a little bare; everything in it was well worn. There was a fine portrait of Father Dunn's predecessor, or, it should rather be said, a poor portrait of a fine man, whose personal goodness and power of doing Christian service shone in his face. Father Miles had been the first priest in that fast-growing inland town, and the captain had known and respected him. He did not say anything now, but sat looking up, much pleased, at the picture. This parlor of the priest's house had a strangely public and impersonal look; it had been the scene of many parish weddings and christenings, and sober givings of rebuke and kindly counsel. Nora gazed about her with awe; she had been brought up in great reverence of holy things and of her spiritual pastors and masters; but she could not help noticing that the captain was a little astray in these first few moments. There stole in upon his pleased contemplation of the portrait a fretful sense of doing an unaccustomed thing, and he could not regain his familiar dignity and self-possession; that conscious right to authority which through long years had stood him in such good stead. He was only a poor, broken down, sick old man; he had never quite understood the truth about himself before, and the thought choked him; he could not speak.

"The masther was coveting to spake with your riverence about Glengariff," ventured Nora timidly, feeling at last that the success of the visit depended wholly upon herself.

"Oh, Glengariff, indeed!" exclaimed the good priest, much relieved. He had discovered the pathetic situation at last, and his face grew compassionate.

"This little girl seems to believe that it would set me up to have a change of air. I haven't been very well, Father Dunn." The captain was quite himself again for the moment, as he spoke. "You may not have heard that the doctors have had hold of me lately? Nora, here, has been looking after me very well, and she speaks of some sea-bathing on your Irish coast. I may not be able to leave my business long enough to do any good. It's going to the dogs, at any rate, but I've got enough to carry me through."

Nora was flushing with eagerness, but the priest saw how white the old captain's fingers were, where they clasped his walking-stick, how blurred and feeble his face had grown. The thought of the green hills and hollows along the old familiar shore, the lovely reaches of the bay, the soft air, the flowery hedgerows, came to his mind as if he had been among them but yesterday.

"I wish that you were there, sir, I do indeed," said Father Dunn. "It is nearer like heaven than any spot in the world to me, is old Glengariff. You would be pleased there, I'm certain. But you're not strong enough for the voyage, I fear, Captain Balfour. You'd best wait a bit and regain your strength a little more. A man's home is best, I think, when he's not well."

The captain and Nora both looked defeated. Father Dunn saw their sadness, and was sure that his kindest duty was to interest this poor guest, and to make a pleasure for him, if possible.

"I can tell you all about it, sir, and how you might get there," he went on hastily, shaking his head to some one who had come to summon him. "Land at Queenstown, go right up to Cork and pass the night, and then by rail and coach next day -- 'tis but a brief journey and you're there. 'Tis a grand little hotel you'll find close to the bay, -- 'twas like a palace to me in my boyhood, with the fine tourists coming and going; well, I wish we were there this day, and I showing you up and down the length of the green country."

"Just what I want. I've been a busy man, but when I take a holiday, give me none of your noisy towns," said the captain, eager and cheerful again.

"You'd be so still there that a bird lighting in the thatch would wake you," said Father Dunn. "Ah, 'tis many a long year since I saw the place. I dream of it by night sometimes, Captain Balfour, God bless it!"

Nora could not keep back the ready tears. The very thought that his reverence had grown to manhood in her own dear country-side was too much for her.

"You're not thinking of going over this summer?" asked the captain wistfully. "I should be gratified if you would bear me company, sir; I'd try to do my part to make it pleasant." But the good father shook his head and rose hastily, to stand by the window that looked out into his little garden.

"We'd make a good company," said he presently, turning toward them and smiling, "with young Nora here to show us our way. You can't have had time yet, my child, to forget the old roads across country!" and Nora fairly sobbed.

"Pray for the likes of me, sir!" she faltered, and covered her face with her hands. "Oh, pray for the masther too, your riverence Father Dunn, sir; 'tis very wake he is, and 'tis mesilf that's very lonesome in Ameriky an' I'm afther laving the one I love!"

"Be quiet, now!" said the priest gravely, checking her with a kindly touch of his hand, and glancing at Captain Balfour. The poor old man looked in a worried way from one to the other, and Father Dunn went away to fetch him a glass of wine. Then he was ready to go home, and Father Dunn got his hat and big cane, pleading that an errand was taking him in the same direction.

"If I thought it would do me any good, I would start for that place we were speaking of to-morrow," said the captain as they set forth. "You know to what I refer, the sea-bathing and all." The priest walked slowly; the captain's steps grew more and more faltering and unsteady. Nora Connelly followed anxiously. There flitted through Father Dunn's mind phrases out of the old Bible story -- "a great man and honorable;" "a valiant man and rich," "but a leper;" the little captive maid that brought him to the man of God. Alas, Father Dunn could tell the captain of no waters of Jordan that would make him a sound man; he could only say to him, "Go in peace," like the prophet of old.

When they reached home the household already sought the captain in despair, but it happened that nobody was in the wide, cool hall as they entered.

"I hope that you will come in and take a glass of wine with me. You have treated me with brotherly kindness, sir," said the master of the house; but Father Dunn shook his head and smiled as he made the old man comfortable in a corner of the broad sofa, taking his hat and stick from him and giving them to Nora. "Not to-day, Captain Balfour, if you will excuse me."

The captain looked disappointed and childish. "I am going to send you a bottle of my father's best old madeira," he said. "Sometimes, when a man is tired out or has a friend come in to dine" -- But he was too weary himself to finish the sentence. The old house was very still; there were distant voices in the garden; a door at the end of the hall opened into an arbor where flickers of light were shining through the green vine leaves. Everything was stately and handsome; there was a touch everywhere of that colonial elegance of the captain's grandfather's time which had never been sacrificed to the demon of change, that restless American spirit which has spoiled the beauty of so many fine and simple old houses.

The priest was used to seeing a different sort of household interior, his work was among the poor. Then he looked again at the house's owner, an old man, sick, sorry, and alone. "God bless you, sir," he said. "I must be going now."

"Come and see me again," said the

captain, opening his eyes. "You are a good man; I am glad to

have your blessing." The words were spoken with a manly

simplicity and directness that had always been liked by Captain

Balfour's friends. "Nora," he whispered, when Father Dunn had

gone, "we'll say nothing to Mrs. Nash. I must rest a little

while here before we get up the stairs."

IV.

Toward the end of the summer, things had grown steadily worse, and Captain Balfour was known to be failing fast. The clerks had ceased to come for his signature long before; he had forgotten all about business and pleasure too, and slept a good deal, and sometimes was glad to see his friends and sometimes indifferent to their presence. But one day when he felt well enough to sit in his great chair by the window he told Mr. Barton, his good friend and lawyer, that he wished to attend to a small matter of business. "I've arranged every thing long ago, as an aging man should," he said. "I don't know that there's any hurry, but I'll mention this item while thinking of it. Nora, you may go down stairs," he said sharply to the girl, who had just entered upon an errand of luncheon or medicine, and Nora disappeared; she remembered afterward that it was the only time when, of his own accord and seeming impatience, he had sent her away.

Reilly and Mrs. Nash bore no ill-will toward their young housemate; they were reasonable enough to regard Captain Balfour's fondness for her with approval. There was something so devoted and single-hearted about the young Irish girl that they had become fond of her themselves. They had their own plans for the future, and looked forward to being married when the captain should have no more need of them. It really hurt Mrs. Nash's feelings when she often found Nora in tears, for the desperate longing for home and for Johnny Morris grew worse in the child's affectionate heart instead of better.

One day Reilly had gone down town, leaving the captain asleep. Nora was on guard; Mrs. Nash was at hand in the next room with her sewing, and Nora sat still by the window; the captain was apt to sleep long and heavily at this time of the day. She was busy with some crocheting; it was some edging of a pattern that the sisters of Kenmare had taught Johnny Morris's mother. She gave a little sigh at last and folded her hands in her lap; her gray Irish eyes were blinded with tears.

"What's the matter, child?" asked the captain unexpectedly; his voice sounded very feeble.

Nora started; she had forgotten him and his house.

"Will you have anything, sir?" she asked anxiously.

"No, no; what's the matter, child?" asked the old man kindly.

"'Tis me old story; I'm longing for me home, and I can't help it if I died too. I'm like a thing torn up by the roots and left in the road. You're very good, sir, and I would never lave the house and you in it, but 'tis home I think of by night and by day; how ever will I get home?"

Captain Balfour looked at her compassionately. "You're a good girl, Nora; perhaps you'll go home before long," he said.

"'Tis sorra a few goes back; Ameriky's the same as heaven for the like o' that," answered Nora, trying to smile, and drying her eyes. "There's many'd go back too but for the presents every one looks to have; 'twould take a dale of money to plase the whole road as you pass by. 'Tis a kind of fever the young ones has to be laving home. Some laves good steady work and home and friends, that might do well. There's getting to be fine chances for smart ones there with so many laving."

"Yes, yes," said the captain; "we'll talk that over another time, I want to go to sleep now;" and Nora flushed with shame and took up her crocheting again. "'Twas me hope of growing rich, and me aunt's tongue shaming me that gets the blame," she murmured to herself. The sick man's hands looked very white and thin on the sides of his chair; she looked at them and at his face, and her heart smote her for selfishness. She was glad to be in America, after all.

They never said anything to each other

now about going to Glengariff; a good many days slipped by when

the captain hardly spoke except to answer questions; but in

restless evenings, when he could not sleep, people who passed by

in the street could hear Nora singing her old familiar songs of

love and war, sometimes in monotonous, plaintive cadences that

repeated and repeated a refrain, sometimes in livelier measure,

with strange thrilling catches and prolonged high notes, as a

bird might sing to its mate in the early dawn out in the wild

green pastures. The lovely weird songs of the ancient Irish

folk, how old they are, how sweet they are, who can tell? but

now and then a listener of the new world of the western seas

hears them with deep delight, hears them with a strange, golden

sense of dim remembrance, a true, far-descended birthright of

remembrance that can only come from inheritance of Celtic blood.

When the frost had fallen on the old garden, Captain Balfour died, and his year of trouble was ended. Reilly and Mrs. Nash, the cook and Nora, cried bitterly in the kitchen, where the sudden news found them. Nobody could wish him to come back, but they cried the more when they thought of that. There was a great deal said about him in the newspapers; about his usefulness in town and State, his wealth, his character, and his history; but nobody knew so well as this faithful household how comfortable he had made his lonely home for other people; and those who knew him best thought most of his kindness, his simple manliness, and sincerity of word and deed.

The evening after the funeral, Nora was all alone in her little room under the high roof. She sat on the broad seat of a dormer window, where she could look far out over the city roofs to a glimpse of the country beyond. There was a new moon in the sky, the sunset was clear, the early autumn weather was growing warm again.

The old house was to belong to a nephew of the captain, his only near relative, who had spent a great many years abroad with an invalid wife; it was to be closed for the present, and Mrs. Nash and Mr. Reilly were to be married and live there all winter, and then go up country to live in the spring, where Mrs. Nash owned a little farm. She was of north of Ireland birth, was Mrs. Nash; her first husband had been an American. She told Nora again and again that she might always have a home with her, but the fact remained that Nora must find herself a new place, and she sat in the window wondering with a heavy heart what was going to happen to her. All the way to the burying-ground and back again in the carriage, with the rest of the household, she had sobbed and mourned, but she cried for herself as much as for the captain. Poor little Irish Nora, with her warm heart and her quick instincts and sympathies! how sadly she thought now of the old talk about going to Glengariff; she had clung long to her vain hope that the dream would come true, and that the old captain and his household were all going over seas together, and so she should get home. Would anybody in America ever be so kind again and need her so much as the captain?

Some one had come to the foot of the stairs and was calling Nora loudly again and again. It was dark in the upper entryway, however bright the west had looked just now from her window. She left her little room in confusion; she had begun already to look over her bits of things, her few clothes and treasures, before she packed them to go away, Mrs. Nash seemed to be in a most important hurry, and said that they were both wanted in the dining-room, and it was very pleasant somehow to be wanted and made of consequence again. She had begun to feel like such an unnecessary, stray little person in the house.

The lamps were lighted in the handsome old dining-room, it was orderly and sedate; one who knew the room half expected to see Captain Balfour's fine figure appear in the doorway to join the waiting group. There were some dark portraits on the wall, and the old Balfour silver stood on the long sideboard. Mrs. Nash had set out all the best furnishings, for this day when the master of the house left it forever.

There were not many persons present, and Nora sat down, as some one bade her, feeling very disrespectful as she did it. Mr. Barton, the lawyer, began to read slowly from a large folded paper; it dawned presently upon Nora that this was the poor captain's will. There was a long bequest to the next of kin, there were public gifts, and gifts to different friends, and handsome legacies to faithful Mrs. Nash and James Reilly, and presently the reading was over. There was something quite grand in listening to this talk of thousands and estates, but little Nora, who had no call, as she told herself, to look for anything, felt the more lonely and friendless as she listened. There was a murmur of respectful comment as the reading ended, but Mr. Barton was opening another paper, a small sheet, and looked about him, expecting further attention.

"I am sure that no one will object to

the carrying out of our deceased friend's wishes as affirmed in

this more recent memorandum. Captain Balfour was already infirm

at the time when he gave me the directions, but, as far as I

could judge, entirely clear in his mind. He dictated to me the

following bequest and signed it. The signature is, I own, nearly

illegible, but I am sure that, under the somewhat affecting

circumstances, there will be no opposition."

"I desire" (read Mr. Barton slowly), -- "I desire the executors of my will to pay five hundred dollars within one month after my death to Nora Connelly; also, to secure her comfortable second-class passage to the port of Queenstown, in Ireland. I mean that, if she still desires, she may return to her home. I am sensible of her patience and kindness, and I attempt in this poor way to express my gratitude to a good girl. I wish her a safe return, and that every happiness may attend her future life.

"'Tis a hundred pounds for ye an' yer passage, me darlin'," whispered the cook excitedly. "'Tis mesilf knew you wouldn't be forgotten an' the rist of us so well remimbered. 'Tis foine luck for ye; Heaven rist his soul, the poor captain!"

Nora was sitting pale and silent. She

did not cry now; her heart was deeply touched, her thoughts flew

homeward. She seemed to hear the white waves breaking about the

ship, and to see the far deep colors of the Irish shore. For

Johnny had said again and again that if they had a hundred

pounds and their two pairs of hands, he could do as well with

his little farm as any man in Ireland.

"Sind for your lad to come over,"

urged Cousin Donahue, a day later, when the news had been told;

but Nora proudly shook her head. She had asked for her passage

the very next week. It was a fine country, America, for those

with the courage for it, but not for Nora Connelly, that had

left her heart behind her. Cousin Donahue laughed and shook his

head at such folly, and offered a week's free lodging to herself

and Johnny the next spring, when she'd be the second time a

greenhorn coming over. But Nora laughed too, and sailed away one

Saturday morning in late October, across the windy sea to

Ireland.

V.

Again it was gray twilight after a short autumn day in the old country, and a tall Irish lad was walking along the high-road that led into Kenmare. He was strong and eager for work, but his young heart was heavy within him. The piece of land which he held needed two men's labor, and work as he might, he must fall behind with his rent.

It was three years since that had happened before, and he had tried so hard to do well with his crops, and had even painfully read a book that was wise about crops which the agent had lent him, and talked much besides with all the good farmers. It was no use, he could not hold his own; times were bad and sorrowful, and Nora was away. He had believed that, whatever happened to her fortunes, he should be able in time to send for her himself and be a well-off man. Oh, for a hundred pounds in his pocket to renew his wornout land! to pay a man to help him with the new ditching. Oh, for courage to fight his way to independence on Irish ground! "I've only got my heart and my two hands, God forgive me!" said Johnny Morris aloud. "God be good to me and Norry, and me poor mother! May be I'll be after getting a letter from me darling the night; 'tis long since she wrote."

He stepped back among the bushes to let a side-car pass that had come up suddenly behind him. He recognized the step of Dinny Killoren's fast pacer, and looked to see if there were room on the car for another passenger, or if perhaps Dinny might be alone and glad to have company. There was only Dinny himself and a woman, who gave a strange cry. The pacer stopped, and Johnny's heart beat within him as if it would come out of his breast. "My God, who's this?" he said.

"Lift me down, lift me down!" said the girl. "Oh, God be thanked, I'm here!" And Johnny leaped forward and caught Nora Connelly in his arms.

"Is it yoursilf?" he faltered, and Nora said, "It's mesilf indeed, then." Dinny Killoren laughed aloud on the side-car, with his pacer backing and jumping and threatening to upset all Nora's goods in the road. There was a house near by; a whiff of turf smoke, drifting low in the damp air, blew into Nora's face; she heard the bells begin to ring in Kenmare. It was the evening of a saint's day, and they rang and rang, and Nora had come home.

Dinny Killoren laughed aloud on the side-car.

So she married the lad she loved, and

was a kind daughter to his mother. They spent a good bit of the

captain's money on their farm, and gave it a fine start, and

were able to flaunt their prosperity in the face of that unkind

aunt who had wished to make them spend their lives apart. They

were seen early on market days in Kenmare, and Nora only laughed

when foolish young people said that the only decent country in

the world was America. Sometimes she sat in her doorway in the

long summer evening and thought affectionately of Captain

Balfour, the poor, kind gentleman, and blessed herself devoutly.

Often she said a prayer for him on Sunday morning as she knelt

in the parish church, with flocks of blackbirds singing outside

among the green hedges, under the lovely Irish sky.

"A Little Captive Maid" first

appeared in Scribner's Magazine (10:743-759), December

1891, and was collected in A Native of Winby, from

which this text is taken.

[ Back ]

Kenmare: A town in extreme southern

Ireland.

[ Back ]

faix: faith.

[ Back ]

O Dea! O Dea!: This exclamation has

not been located in a dictionary. Clare Galvin has suggested

that "Dea" is an anglicized rendering of the Gaelic "Dia,"

meaning "God." Clare Galvin is a descendent of

Jewett-family employees, Mary and Katy Galvin.

19th-century Irish Catholics would be familiar with the Latin

"Deo," also meaning "God."

[ Back ]

wept for her wandering children: See

Matthew 2:17-18.

[ Back ]

The girl I left behind me: Samuel Lover (1797-1868), was an Irish writer, painter, and composer. One of his most famous songs is "The Girl I Left Behind Me." See his Songs and Ballads (1859). Wikipedia discusses several versions of the song and provides the following example of lyrics that would be appropriate in this context:

All the dames of France are fond and free

And Flemish lips are really willing

Very soft the maids of Italy

And Spanish eyes are so thrilling

Still, although I bask beneath their smile,

Their charms will fail to bind me

And my heart falls back to Erin's isle

To the girl I left behind me.

(Research assistance, Betty Rogers).

[ Back ]

Pride of Glencoe: This traditional Irish song begins:

As

I was a walking one evening of late

Where Flora's green mantle the fields decorate

I

carelessly wandered, where I do not know

By

the banks of a fountain that lies in Glencoe

Like she who the pride of Mount Ida had won

There approached a wee lassie as fair as the sun

With

ribbons and tartans around her did flow

That

once won MacDonald, the pride of Glencoe

(Research: Gabe Heller)

[ Back ]

Inniskillen Dragoon: This traditional Irish song begins:

Fare thee well Enniskillen, fare

thee well for a while

And all around the borders of

Erin's green isle

And when the war is over we'll

return in full bloom

And we'll all welcome home the

Enniskillen Dragoons.

(Research: Gabe Heller).

[ Back ]

Gengariff: Town near Bantry on

Bantry Bay in southern Ireland.

[ Back ]

light-horseman: a lightly armed

member of cavalry.

[ Back ]

Whiddy Island: An Island in Bantry Bay.

[ Back ]

Baltimore ... Bantry: Both of these

towns are at the southern tip if Ireland.

[ Back ]

shebeen: In Ireland, an unlicenced

house where liquor is sold illegally.

[ Back ]

sin of staling: stealing.

[ Back ]

Florida Keys: a string of small

islands off the southwestern coast of Florida.

[ Back ]

makes the stations: "Also called

THE WAY OF THE CROSS, a series of fourteen pictures or carvings

portraying events in the Passion of Christ, from his

condemnation by Pontius Pilate to his entombment. The series of

stations is as follows: (1) Jesus is condemned to death, (2) he

is made to bear his cross, (3) he falls the first time, (4) he

meets his mother, (5) Simon of Cyrene is made to bear the cross,

(6) Veronica wipes Jesus's face, (7) he falls the second time,

(8) the women of Jerusalem weep over Jesus, (9) he falls the

third time, (10) he is stripped of his garments, (11) he is

nailed to the cross, (12) he dies on the cross, (13) he is taken

down from the cross, (14) he is placed in the sepulchre. The

images are usually mounted on the inside walls of a church or

chapel but may also be erected in such places as cemeteries,

corridors of hospitals, and religious houses and on

mountainsides." (Source: Britannica Online).

[ Back ]

purple fox-glove ... Fairy Fingers:

A tall plant with purple or white flowers that look like glove

fingers.

[ Back ]

Queenstown ... Cork: The

town of Cobh in County Cork on Cork Harbor is a seaport and

naval station. It was renamed Queenstown in 1849 to honor Queen

Victoria. The town retained this name until 1922. It is still

the chief Irish port of call for transatlantic liners. A town

near Bantry on Bantry Bay in southern Ireland. (Source: Encyclopedia

Britannica; Research assistance: Chris Butler).

[ Back ]

phrases out of the old Bible story ...

"a great man and honorable;" "a valiant man and rich," "but a

leper": See 1 Kings 5.

[ Back ]

"Go in peace": Many prophets,

including Christ, in the Old and New Testaments have sent people

away with the wish that they "go in peace."

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College.

Main Contents & Search

A Native of Winby