By Captain A. T. Mahan, U. S. N.

This text appeared in two issues of Scribner's Magazine,

vol. 24, 1898: July pp. 22-36; August pp. 204-219.

FIRST PAPER

IT is a somewhat singular circumstance that the most renowned battle of the United States Navy during the Revolutionary War -- one of the most illustrious, also, fought at any time under any flag -- while it certainly and deservedly redounds to the glory of America, represents above all the remarkable personal qualities of a single man, who at that period of his career rather disavowed than rejoiced in the name of American. "Though I have drawn my sword in the present generous struggle for the rights of men," wrote Paul Jones to the Countess of Selkirk, in May, 1778, "yet I am not in arms as an American. I profess myself a citizen of the world, totally unfettered by the little mean distinctions which diminish the benevolence of the heart and set bounds to philanthropy." "I have drawn my sword only from motives of philanthropy, and in support of the dignity of human nature," he tells the French Minister of Marine a few months later. Jones served well the cause to which he thus devoted himself, and was among the first to come forward to sustain it upon the sea; but if he enunciated such visionary sentiments upon the quarter-deck, or round the mess-tables, of the vessels upon which he sailed in the early part of the war, that circumstance, and the fact of his foreign birth, may have given rise to the doubts of his fidelity, which his correspondence shows to have arisen among the hard-headed, practical, and wholly unsentimental seamen embarked in the same cause. In the hour of civil strife, the native of one section of the country who throws in his lot with the other cannot wholly avoid the suspicions of his neighbors. It was notoriously so with officers of Southern birth, who during the Civil War of 1861-65 ranged themselves on the side of the Union. Farragut himself did not escape the doubt at the first; although he, like Jones, had willingly sacrificed his nearest personal interests to conviction of right.

The motley crew of the Bonhomme Richard, gathered from many nationalities, and controlled to common action only by the invincible energy of its commander, might, without much straining of analogies, be considered the complement of his own fanciful ideal, the realization, though somewhat disreputable, of a world-citizenship unfettered by any mean distinctions of patriotism or of party. The experiences he had of their fidelity might well have suggested to Jones a doubt as to whether the great ends of universal humanity are best served by such a forced disregard of the narrower and more intense ties which bind man to man in the smaller groups, whose rivalries and frictions promote, rather than retard progress. Fortunately, before the hour of extreme trial arrived, a reinforcement of Americans, lately released from captivity in England, afforded a nucleus, unified by the paltry sentiment of common origin and common interests, round which the heterogeneous elements of the majority could cling and crystallize. There was a droll story current in the United States Navy after 1812, that to a lieutenant sent with a flag of truce to a British blockading ship, the commander of the latter expressed surprise at the result of some of the single-ship actions. "Half your crews, you know, are British," said he. "Well," replied the lieutenant, "the other half are Americans, and that, I presume, makes the difference." The Americans in the Bonhomme Richard's crew were a minority; but they flavored it as salt does food, and they were led by a lion.

It would give a very imperfect idea of John Paul Jones, however, were the impression allowed to remain, uncorrected, that he was distinguished merely by extraordinary energy, valor, and endurance. On the contrary, he belongs to that class of true sea-kings, whose claim to the title lies in the qualities of the head as well as of the heart. In the latter, indeed, there was with him an alloy of baser metal, of self-seeking, to which fault of our common manhood the narrow fervor of patriotism -- love of home and of country -- affords a better corrective than the vague philosophical prattle of the eighteenth century, with its Rights of Man and its citizenship of the world. Jones possessed considerable originality of ideas, resultant upon his insight into conditions round him and his appreciation of their relative value; and this quick natural perception received direction and development from habits of steady observation and ordered thought. He was also, notwithstanding his superb self-reliance, a man conscious of his deficiencies as well as of his powers; intent therefore upon self-improvement, upon the acquisition of knowledge and of experience.

From the time that the American Revolution drew him away, in 1775, from the schemes formed a year or two before, of quitting "the sea-service in favor of calm contemplation and poetic ease, the affections of the heart and the prospects of domestic happiness," he gave himself to thinking, widely and closely, how the struggle could be carried on most advantageously, and how he could best fit himself to play a prominent part as the contest grew and spread. "To be diffident," he wrote in 1782, to the United States Minister of Marine, "is not always a proof of ignorance, but sometimes the contrary. I was offered a captain's commission at the first, to command the Providence, but declined itÖ. I had sailed before this Revolution in armed ships and frigates, yet when I came to try my skill, I am not ashamed to own I did not find myself perfect in the duties of a first lieutenant. If midnight study, and the instruction of the greatest and most learned sea-officers, can have given me advantages, I am [now] not without them. I confess, however, I have yet to learn. It is the work of many years' study and experience to acquire the high degree of science necessary for a great sea-officer. Cruising after merchant-ships, the service in which our frigates have generally been employed, affords, I may say, no part of the knowledge necessary for conducting fleets and their operations."

Upon this follows a number of practical suggestions for the development of the United States Navy, illustrated by facts and events drawn from naval history, remote and recent, which show, beyond the possibility of a doubt, the extent of his information and his industry in acquiring it That his knowledge was not raw, but well digested, is equally evident from his reflections and conclusions. Though Scotch by birth, his professional thought, as there shown, bears clear traces of the association which he diligently sought with the first French officers of the day, whose eager scholar he was while his little ship lay in port amid their great fleets. Let it be remembered, too, that the man who in 1782 wrote the words quoted, humbly confessing his defects, had three years before fought a frigate-fight excelled by none for tenacity of purpose and desperate valor; had had his ship there sink under his feet; had received sword and medal from the King of France, the thanks of his adopted country, the compliments of Washington. Where such strength of head and of heart meet, only opportunity is wanting to bring great events to pass. One opportunity only Jones had. It was not equal to his qualities, but the event will never pass from men's memories.

John Paul Jones was born in 1747, in the parish of Kirkbean, upon the Solway Firth, in the southwestern part of Scotland. His family name was Paul, that of Jones being assumed later. Thirty miles south of Kirkbean, on the other side of the Frith, and therefore in England, is the port of Whitehaven, whence he sailed during the early part of his maritime career, which began at the age of twelve. His voyages, of which, however, only an incomplete record remains, were chiefly to the West Indies and to the North American continent. In the latter an elder brother, William Paul, had settled at Fredericksburg, in Virginia. There John Paul visited him from time to time, as opportunity offered; and when William died, in 1773, leaving a considerable property, John went there to live and to settle the estate. It was then that he formed the purpose, before quoted, of abandoning the sea; moved thereto, doubtless, by the prospect of a reasonable competence which had thus opened to him.

The troubles of the colonies with the mother-country, however, had begun already. A recent settler, without family ties on the spot, with sisters in Scotland, Jones very well might have remained at least passively a loyalist; but he was a reading man always, and had imbibed, as before remarked, the ideas and the jargon of the century. With his native temperament and capacities, it was well nigh impossible that he should remain inactive in such stirring times, while his acquired views, his new interests, and the weakening hold of home affections, consequent upon absence since boyhood, combined to impel him to take sides with the fellow-citizens among whom he was then living, rather than with those in the old country. For this he was called then a traitor; not wholly unnaturally, for the doctrine of indefeasible allegiance was still maintained by Great Britain. It is singular, however, to find him again so styled in a very recent English work. A rebel he doubtless was; a traitor, perhaps, technically, as Washington might be called for the same reason; but he betrayed no trust. The disproportion of the term measures the intensity of the alarm caused on the coasts of England, by a man who clearly understood the value of the offensive, and brought the ravages of war home to a government which -- from the American point of view -- was inflicting upon its enemies sufferings wanton, or at the least excessive. If Paul Jones be a traitor, what epithet is left for Benedict Arnold?

His first cruise in the Revolution was made in this subordinate capacity, as first lieutenant of the Alfred, of thirty guns, the flagship of a small squadron under Commodore Esek Hopkins, the commander-in-chief of the new navy. The expedition sailed February 17, 1776, from the capes of the Delaware, and went to the Bahama Islands, where a certain amount of injury was done to British interests; but upon the whole the enterprise was not successful, and a rencounter with a British man-of-war off Block Island was considered to result discreditably. In this censure Jones was not involved, and soon after returning to the United States he was ordered, on the 10th of May, 1776, to command the Providence, a very small vessel mounting twelve four-pounders.

The British expeditions against New York under the two Howes were now approaching the coast, from Halifax and England, and maritime activity naturally increased as summer drew near. Jones was at first employed in convoying duty, but in August, 1776, he sailed "on a cruise," with orders largely discretionary. After a few days spent in the neighborhood of Bermuda, his enterprising spirit led him again to the enemy's coast, in the waters between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island, where he entered the principal ports, taking possession of the fishery and the shipping, which he either burned or carried away. His entire absence was something less than seven weeks, in the course of which he sent into port, or destroyed, sixteen prizes.

What is chiefly interesting in these incidents, trivial in their immediate results, is the clear impression left upon his mind of the essential importance of a navy to the American cause, and that the best use to be made of the small force that could be put afloat was to direct it, not so much upon the enemy's commerce at sea, in transit, as upon his coasts and commercial stations, where his shipping would be found congregated, with insufficient local protection. Commerce-destroying, to use the modern phrase for an age-long practice, is a wide term, covering many different methods of application. In essence, it is a blow at the communications, at the resources, of a country; in system, it should be pursued not by random prowling, by individual ships for individual enemies, as they pass to and fro, but by dispatching adequate force to important centres, where the hostile shipping for any reason is known to accumulate. From his experience as a mariner, and from his habits of observation and reflection, Jones knew in his day that there were many such exposed points in the British dominions, on their coasts. Small squadrons directed upon them could do a maximum amount of injury; for the shipping caught in a defenceless port would be without the power of escape, and could be destroyed also without embarrassment concerning the disposition of prisoners, who would need only to be landed. Let a single ship of war -- commerce-destroyer -- meet twenty or thirty merchant-ships at sea, he can take but a few; the rest scatter and escape, and the prisoners must be cared for. Corner the same squadron in port, and neither difficulty, as a rule, exists. Moreover, Jones's plan contemplated destruction, not capture; injury to the enemy, not prize-money primarily. The latter he recognized as a necessary concession to the sordid weakness of the mass of mankind; for himself, glory, distinction, was the prime motive. This is satisfactorily shown, not only by the general utterances of his letters, which might be forced, but by his plans and his acts. Self-seeking in him took the shape of loving military success, not money.

Some quotations from his writings at this period will illustrate his accurate perception of conditions. Jones was not called upon -- more is the pity -- to play a part in a great navy, but to adapt very limited means to the attainment of considerable ends. Immediately upon his return from this cruise of the Providence, he wrote to Robert Morris, then President of the Marine Committee of Congress, echoing the words of Washington: "Without a respectable navy -- alas! America! It is to the last degree distressing to contemplate the state and establishment of our navy. We enlist men, but the privateers entice them away as fast as they receive their month's pay. The common class of mankind are actuated by no nobler principle than that of self-interest; this, and this alone, determines all adventures in privateers -- the owners as well as those whom they employ. While this is the case, unless the private emoluments of individuals in our navy is made superior to that in privateers, it can never become respectable, it can never become formidable." He suggests, therefore, that all the profits from prizes by naval vessels should be given to the crews. At the same time he showed the desirability of a renewed attempt against the fishing fleet at Cape Breton Island and the coaleries there, as well as to release a number of Americans forced to labor in the mines; and he advises, in the same general line of naval enterprise, that "an expedition of importance may be effected this winter on the coast of Africa with part of the original fleet" -- that is, of the ships first bought into the navy, as distinguished from others ordered to be built and now approaching completion. Three ships which he names, "would, I am persuaded, carry all before them, and give a blow to the English African trade which would not soon be recovered, by not leaving them a mast standing on that coast." Here again Jones spoke from personal knowledge and observation, having twice, at least, visited the African coast in slavers.

About a year later he summed up his views on the naval policy of America, in a letter to the United States Commissioners in Paris. Though further developed and more explicit, the ideas were identical with those before enunciated, which they illustrate and confirm. "I have always, since we had ships of war, been persuaded that small squadrons could be employed to far better advantage on private expeditions, and would distress the enemy infinitely more, than the same force could do by cruising either jointly [that is, the whole navy together] or separately [as single cruisers]. Were strict secrecy observed on our part, the enemy have many important places in such a defenceless situation that they might be effectually surprised and attacked, with no very considerable force. We cannot yet fight their navy, as their numbers and force are so far superior to ours. Therefore it seems to be our most natural province to surprise their defenceless places, and thereby divert their attention and draw it from our coasts." This expresses decisively the career that Jones, throughout the Revolutionary War, proposed to follow - to pursue the enemy, not in occasional merchant-ships, but where great interests were concentrated and inadequately protected; and to do so not with a single ship, seeking to snatch a hasty morsel, but with a squadron, capable of deliberately insuring the destruction of the enemy rather than its own profit. Such a conception places its author far above the level of the mere prize-seeker, as well in loftiness of purpose as in breadth of view. It may be added that the great and truly influential successes of commerce-destroying - as distinguished from control of the sea - in modern times, successes associated with such illustrious names as Jean Bart, Forbin, Du Guay Trouin, were obtained by following the same system; by hard-fighting squadrons, not by merely booty-seeking ships. The celebrated cruise of the Essex in 1813-14 illustrated Jones's principles; for it was directed by sudden surprise against an exposed and concentrated industry of the enemy, and, although begun by a single ship, her captain at once constituted for himself a squadron, by using the best of his prizes.

Some obscurity hangs over the process by which Jones impressed upon Congress his own peculiar fitness for carrying the war of destruction home to Great Britain. His local knowledge of her shores doubtless counted for something, his audacity and success upon the shipping of Cape Breton for more. There may also have been a disposition to remove him from American waters, and from immediate contact with other captains of the navy. Some of these looked upon him with suspicion, as perhaps lukewarm toward America. "I have asked Captain Saltonstall," he writes to Commodore Hopkins, "how he could in the beginning suspect me, as you have told me, of being unfriendly to America. He seemed astonished at the question; and told me it was yourself who promoted it." "I have even been blamed," he says, in another place, "for the civilities which I have shown my prisoners." There may also have been some idea of compensation for wrong done him; for in the reorganization of the navy, October 10, 1776, though Jones was retained as captain, there were placed over his head thirteen men who were not there when he was first commissioned, "not one of whom," to use his own words, "did (and perhaps some of them durst not) take the sea against the British flag at first." If Jones's account can be accepted, this injustice, for such it assuredly was, was due to what is commonly styled political influence - an influence which has its own sphere in politics, but is apt to work disaster and injustice when its power is intruded where other motives and considerations should prevail. A member of the Continental Congress, writing to him, said: "You would be surprised to hear what a vast number of applications are continually making for officers of the new frigates, especially for the command. The strong recommendations from those provinces where any frigates are building have great weight."

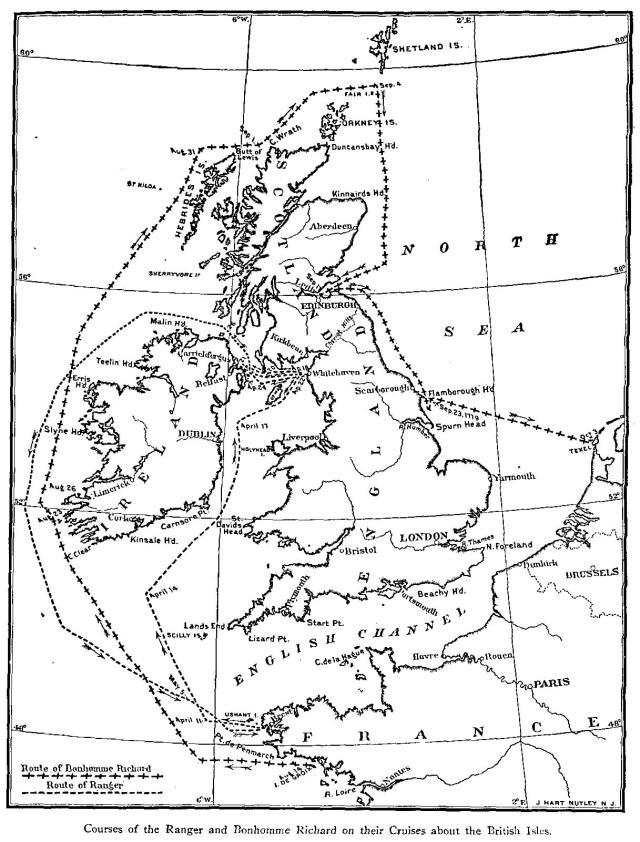

The shortest way of repairing the injury done was to send Jones to Europe, where he would have no superior officer, and would be free to work out his own plans. He was first ordered to go to France, as passenger in a French vessel, the Amphitrite; but this was soon changed, and by a resolution of Congress, June 14, 1777, he was put in command of the Ranger, a new ship, built at Portsmouth. She carried eighteen six-pounder guns. On board her Jones hoisted, for the first time in the American Navy, the new national flag, of thirteen stripes and thirteen stars. On November 1st she sailed for France, carrying dispatches with the news of Burgoyne's surrender, which was to determine Louis XVI. to recognize the independence of the United States; and on December 2d she anchored before Nantes.

As the French court was still vacillating, though inclined to espouse the American quarrel, Jones was instructed carefully to avoid embarrassing it by giving a handle for complaint to Great Britain. "While on the coast of France, or in a French port, you are, as much as you conveniently can, to keep your guns covered and concealed, and to make as little war-like appearance as possible." The British Government was watching the movements in neutral ports, as attentively as the United States officials watched the building of the Alabama and of the Laird rams during the Civil War. This vigilance defeated the expectation, held out to Jones when he sailed, that he should have command of a large frigate, the Indien, carrying the unusual battery of thirty six-pounders, then equipping at Amsterdam. The representations of the British minister prevented the delivery of the ship in Dutch waters, and Jones felt compelled to assent to her being turned over to the French Government after the secret treaty of alliance with the United States was signed, February 6, 1778. As formal war did not yet exist between Great Britain and France, no technical objection was valid against this transfer. The same condition of formal peace still obtained when Jones sailed on his first offensive cruise in the Ranger, on April 10th. The American Commissioners at Paris therefore directed him not to send the prizes he might take to French ports, but to those of Spain; and in case he made an attempt on the coast of Great Britain, he was "advised not to return immediately into the ports of France, unless forced by stress of weather or the pursuit of the enemy; and in such case you can make the proper representations to the officers of the port, and acquaint us with your situation."

Beyond such cautions, Jones's movements were left to his own discretion. In the exercise of this he had already given an instance of that combination of sound judgment with dignified self-assertion -- or, rather, assertion of his country's dignity -- which, having regard to his lack of early training, showed his natural aptitude for affairs. Having to convoy some American merchant-ships to Quiberon Bay, where they were to place themselves under the protection of a French squadron commanded by Lamotte-Piquet, he took the opportunity to obtain an open recognition of the American flag, by saluting the Commodore; having first received, as is customary, the promise of due acknowledgment. The question arose of the number of guns to be fired in return to his own. Jones demanded gun for gun; "the haughty English," he said, "do as much for foreign officers of equal rank;" and he claimed that he was entitled to the same, as being the senior American officer in Europe. Lamotte-Piquet replied that, by the orders of his court, he must, to the ship of a Republic, give four less than he received. Jones would not come within saluting distance until he knew the facts; but then, finding them to be as stated, he waived his claim to the equal number, because any salute at all "was in fact an acknowledge of American Independence" by France - an important political consideration. Again, as he did not reach the anchorage till after dark, and the salute might therefore not be generally seen, he notified the Commodore that we would next day sail through the fleet and salute him in open daylight; which was done, thirteen guns being fired and nine returned.

Upon leaving Brest, on April 10th, Jones steered at once for St. George's Channel, bent upon the destruction of the merchant-shipping in the port of Whitehaven, where conditions were familiar to him from early and long association. It is, perhaps, this readiness, in his character of citizen of the world, and not of an American patriot, to visit with fire and sword the scenes of his childhood, that has intensified the feeling against Jones, among those who do not share the pride of Americans in the luster shed by him upon their flag. Except for some such sentiment, the enterprise was unimpeachable; justifiable by the common practice of war, even without the further plea of retaliation.

On the 18th of April, the Ranger was near the Isle of Man, and at evening stood over toward Whitehaven, between thirty and forty miles distant. At 10 p.m. she was off the harbor, and the landing party ready; but the wind increasing greatly, and blowing directly on shore, Jones thought it imprudent to remain. The ship beat out to sea, and continued cruising between the Irish and Scotch coasts until the evening of the 22d, when the attempt was renewed, but with imperfect results. Owing to a failure of the breeze, she could not get close enough; and the party of thirty-one men, led by Jones himself, having left her at midnight, did not reach the outer pier till day began to dawn. One boat with an officer was sent with combustibles to the north side of the harbor, while Jones himself superintended operations on the south, where were the fortifications intended for the defence of the shipping, but evidently neglected and ungarrisoned. The guns were spiked, but, when it came to firing the vessels, it was found that all the candles had burned out. Those were not the days of lucifer matches. To add to Jones's annoyance, the boat returned from the north side without having done its work; his "wise officer," Jones afterward stated in a memorial to Congress, "observed that it that was a rash thing, and nothing could be got by burning poor people's property." One ship on the south side was at length fired, by means of live coals obtained from a neighboring house, and a barrel of tar poured upon the flames, which began to mount from the hatchways and up the main-mast; but the sun was already an hour high, and, worse, one of the party had deserted and roused the inhabitants. "David Freeman," said a local gazette of the day, naming this deserter, "may in some respects be considered the saviour of this town." The men of the place now came running to the beach in numbers. There was nothing to do but to retire discomfited. This was effected, unharmed the hostile guns being for the time useless. Jones claimed that "had it been possible to have landed a few hours sooner, my success would have been complete. Not a single ship, out of more than two hundred, could possibly have escaped." Estimates of probable achievements are to be received with caution, but the educational and moral effects of what had been done were certain. Wherever the coast defences were not in proper condition, as was the case in many parts of Great Britain, men would fear the repetition of such attempts with worse results.

During this short cruise of the Ranger -- she was absent from Brest only twenty-eight days - there occurred two other incidents, which must be mentioned but briefly, for more important events demand our remaining space. Of these, the first is the taking of silver plate, to the amount of a few hundred pounds, from the house of the Earl of Selkirk. Jones had purposed to seize the persons of one or more distinguished subjects of Great Britain, to hold them as hostages for the treatment of American prisoners; the influence of their friends might prevail to ameliorate conditions, which were retaliated upon them. With this object he landed at the seat of Lord Selkirk. The latter being from home, the scheme failed; but the boat's crew demanded permission to take the family plate, which Jones reluctantly granted, as a concession to the desire for prize-money, the imperiousness of which he recognized. As regards this act of the crew, it must be remembered that, owing to the poverty of the United States at this time, wages were most irregularly paid, a condition which invariably relaxes discipline; and their ears had been filled with stories of similar injuries done to their own people in America. The taking of private property under such circumstances is to be condemned, not as injury, but as useless injury, and therefore unworthy. This Jones felt, and himself bought in and restored the plate. The clearest vindication of his conduct in this affair is to be found in the diary of Gouverneur Morris, when United States Minister at the Court of France. "April 20, 1791. M. de Chatelet has brought hither Lord Dare, who is the son of Lord Selkirk, and who meets here by accident Paul Jones. He acknowledges the polite attention of Jones in the attack on his father's house in the last war." It is to be mentioned also that Lord Selkirk, when acknowledging the receipt of the plate to Jones, wrote: "On all occasions, both now and formerly, I have done you the justice to tell you that you made the offer of returning the plate very soon after your return to Brest." He bore witness also that the transaction was limited to taking such silver as the butler got together, no search being made nor incivility offered.

The other incident was the capture of the British sloop-of-war Drake. This vessel was lying off Carrickfergus, at the entrance of Belfast Lough, both before and after Jones's two attempts on Whitehaven. On the 21st he got sight of her, and that night attempted to board her by surprise; anchoring so that the Ranger would swing alongside. This manúuvre failed, because the anchor was not dropped in time. The ship was disguised as a merchantman, and the cable, being instantly cut, seemed to those on board the Drake to have parted. The Ranger, therefore, beat out to sea undetected, but not unsuspected. The British captain, considering her movements doubtful, unmoored his ship next day, and in so doing, lifted along with his own anchor that of the Ranger, together with a length of cable, showing the marks of cutting. On the 24th the strange sail again appeared, and the Drake weighed; but it falling calm, and the wind afterward coming easterly - ahead -- she was long in getting clear of the bay. While turning slowly out of the harbor, a lieutenant on shore service came on board, to volunteer in room of the first lieutenant of the ship, who had died two days before. He brought with him a letter from Whitehaven, giving an account of Jones's attempt there, and of the force of the American vessel, of whose identity with the one in sight little doubt could remain.

Jones's purpose had been to go in and attack, for which the wind was fair, but he was prevented by a singular incident, which illustrates a class of difficulty he continually encountered. The first lieutenant, who had long been insubordinate, persuaded the crew "that, being Americans, fighting for liberty, the voice of the people should be taken before the captain's orders were obeyed, and they rose in mutiny. Captain Jones was in the utmost danger of being killed or thrown overboard. Fortunately, the Drake was just then seen to be in movement, and at the same time sending a boat. Jones stood out to sea, moving slowly, that he might be overtaken, but keeping the ship's stern toward the boat, that the Ranger's character might not be evident. It thus came alongside and was captured.

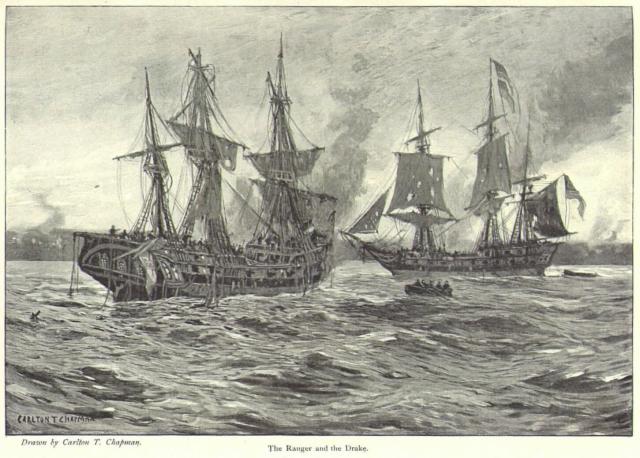

Toward sunset the two vessels were within range. A sharp action ensued, lasting, by Jones's report, one hour and four minutes, when the Drake surrendered. She carried twenty guns; but the principal witness before the court-martial upon the survivors, held eighteen months later, stated that these were 4-pounders, which would make her battery decisively inferior to that of her opponent; and he added that the shot failed to penetrate the enemy's sides. Her crew numbered 154 to the Ranger's 123. The general drift of the evidence, by the officer who surrendered the ship, would show that the British vessel was not kept up to the fighting mark. What explanations her captain would have given, had he lived, cannot be surmised. He was killed by a musket-ball in the head, fifteen minutes before the ship struck, and the lieutenant also fell. Though "nominally of equal force," says an excellent English authority, Professor Laughton, "in reality the Drake was no match for the Ranger; and at this time the crew was mainly composed of newly raised men, without any officers except her captain, and the registering lieutenant of the district, who came on board at the last moment as a volunteer. She had no gunner, no cartridges filled, and no preparation for handling the powder." Her disadvantages were thus similar to those of our own twice unlucky ship, the Chesapeake, when she was brought-to by the Leopard, and when captured by the Shannon. It is only just, however, to take into account that, though the Ranger was the longer in commission, Jones had to meet exceptional difficulties in maintaining her efficiency, which in fact rested, under most depressing circumstances, wholly upon his own personal ascendency.

The Ranger regained Brest May 8, 1778, bringing with her the Drake and two other prizes. A period of disappointment and mortification now awaited Jones. His drafts upon the United States Commissioners at Paris were returned to him dishonored, owing to their want of funds, and it became increasingly difficult to maintain discipline on board, or respect ashore for his position in a foreign port. He wished, therefore, to return to America; but his activity, daring, and the circumstance of his victory over a ship of superior armament, had inclined the court to utilize his abilities, and at the same time to gratify their American allies. "The Minister of Marine (Sartine)," wrote Franklin to the Congressional Committee for Foreign Affairs, "was desirous of employing him in the command of a particular enterprise; and to that end requested us to spare him, which we did, and sent the Ranger home under the command of his lieutenant." Jones accordingly left that ship in June, and she sailed for America the last week in July. He went to Paris, and received at first most cheering assurances of the character and numbers of the ships of war to be assigned to him under the United States flag. "I was flattered," he wrote three months later to Sartine, "with the assurances that three frigates, two tenders, and a number of troops should be immediately put under my command, to pursue such objects as I thought proper." Upon this expectation he danced attendance during the summer and autumn, sometimes in Paris, sometimes in Brest, but all in vain.

He thus lost, moreover, the opportunity of going out with the great French fleet of thirty ships-of-the-line, which put to sea in June, 1778, under Admiral D'Orvilliers, and on July 27th fought a pitched, though indecisive, battle with the British under Keppel. D'Orvilliers, struck with his desire for professional acquirement and distinction, had offered to take him on board the flagship -- a chance which Jones, with his broad views of what constituted professional excellence, was anxious to improve. He believed, however, that the service which he proposed to execute would materially affect the issues of the campaign, by provoking a diversion in a different quarter from that in which the great fleet operated. "I prefer," he wrote to Sartine, "a solid to a shining reputation -- a useful to a splendid command; and I hold myself ready, with the approbation of the American Commissioners at Paris, to be governed by you in any measures that may tend to distress the common enemy." There can be no question that Jones had to an unusual degree man's natural desire for distinction; but his correspondence at this period bears consistent evidence of a yet more honorable ambition to serve his cause well.

The brilliant prospect at first held forth dissolved before the steady opposition of the officers of the French Royal Navy, who, like any other body of men, jealously resisted the proposal to put ships which would naturally fall to them, under the command of a foreigner. They urged, what was perfectly true, that such an assignment would carry an implied slight upon them; and, as they at that day were all of noble birth, their social influence at court could not be overcome by the mere consideration of the exceptional merit of the adventurer whom it was intended to favor. The minister had to recede from his intention to employ ships from the navy, and he fell back upon the expedient of purchasing. On February 4, 1779, he announced to Jones, in somewhat pompous phrase, that "in consequence of the exposition I have laid before the king, of the distinguished manner in which you have served the United States, his majesty has thought proper to place under your command the ship Duras, of forty guns, at present at L'Orient." To this vessel, which was a worn-out East-Indiaman, Jones, with the royal consent, gave the name of Bonhomme Richard, for the following reason. While kicking his heels in enforced idleness at Brest, he found by chance a copy of Dr. Franklin's Almanac, containing the Maxims of Poor Richard. One of them read, "If a man wishes to have any business faithfully and expeditiously performed, let him go on it himself; otherwise, he may send." Jones was then struck with the folly of leaving his application at court in other hands, went there in person, and secured the Duras.

It will be remembered that an essential element in Jones's plans for secondary objects of war, such as he contemplated -- for diversions -- was that small vessels should act in squadrons. There were associated, therefore, with the Bonhomme Richard, four others, viz.: Alliance, 36 guns; Pallas, 30; Cerf, 18; Vengeance, 12. Of these, the Alliance alone was a United States ship, which had arrived in France on February 6, 1779, bringing Lafayette back. She was an exceptionally fast sailer, but the command of her had been given by Congress to a French officer, Pierre Landais. This step, intended as a compliment to an ally, proved most unfortunate. Landais was a man of temper irascible and insubordinate, to the verge of insanity, and he had conceived the idea that, although junior to Jones by date of commission, he was of superior, or at least equal, authority, because his ship was United States property. All the others, including the Richard, belonged to the King of France, but flew the American flag; and their officers, though chiefly French, received temporary commissions from the American Commissioners, for the specific cruise. Also, although Jones was in supreme command, he was to communicate, not only with the American Commissioners, but with the French Minister of Marine, who wrote to him: "You will render me an exact account of each event that may take place during your cruise, as often as you may enter a port under the dominion of the King."

This duplex control naturally became a root of bitterness, which bore fruit on many occasions, and was aggravated by the character of Landais, the second in rank. M. de Chaumont, the representative of the Minister of Marine, imposed upon Jones, before sailing, a "concordat," signed by the representative and the five captains. Although chiefly concerned with the distribution of prize-money, this paper was intended also to reserve certain rights to each vessel, and in fact made of the squadron a confederacy rather than a military unit. Its spirit is best indicated by Chaumont's letter to Jones: "The situation of the officers who have accepted commissions from Congress to join the expedition of the ship Bonhomme Richard, which you command, may be in contradiction with the interests of their own ships; this induces me to request you to enter into an engagement with me, that you shall not require from the said vessels any services but such as will be conformable with the orders which those officers shall have," etc. Thus, instead of Jones being absolute, responsible only to his superiors, every subordinate captain had ground for questioning his particular orders. In short, although the ships all bore a strictly public character, reinforced by the United States' commissions to their officers, the enterprise as a whole embodied some of the worst partnership features of a private, or privateering, expedition, by which name it was occasionally called. "I was anxious," wrote Jones, after the Revolution, "to force some ill-natured persons to acknowledge that, if they did not tell a wilful falsehood, they were mistaken when they asserted that I 'had commanded a squadron of privateers.'"

Under these discouraging conditions the squadron left L'Orient, the port of equipment, on June 13, 1779. On the 30th it returned to Groix Roads, outside of L'Orient, having made a short cruise in the Bay of Biscay. The Richard had proved to be slow, as she was before known to be unsound and worn out. "It is the constructor's opinion," wrote Jones, on July 12th, "that she is too old to admit of the necessary alterations. Thus circumstanced, I wish to have an opportunity of attempting an essential service, to render myself worthy of a better and faster-sailing ship." He received now from Franklin some modifications in his instructions. Originally, as issued April 28, 1779, these had contemplated landings on different points of the British coast, for which many varied suggestions were made by Jones's active mind; and it was then intended that Lafayette should command the soldiers embarked. This fell through, partly because the particular designs adopted leaked out; chiefly, probably, because, in consequence of detentions so far incurred, the time was now near for executing a proposed grand scheme for an invasion of England. A Franco-Spanish fleet was to enter the Channel -- and actually did enter it, to the number of sixty-six ships-of-the-line, somewhat later -- under cover of which the passage of the troops was to be made. In this invading army Lafayette was to command a regiment, and it was not expected nor desired that Jones's ships, intended to operate a strong diversion, should get back before the crossing began.

The instructions now received by Jones, dated Passy, June 30, 1779, represented the wishes of the French court, though coming through the American Commissioners. "As it is at the chief expense," wrote Franklin, "I think they have the best right to direct." The project of landings, in force sufficient to cause damage, beyond ransom and a certain amount of local panic, was abandoned, and for it was substituted a cruise at sea, incidental to which a hurried descent, such as at Whitehaven, might be casually attempted, as opportunity afforded. "You are to make the best of your way," wrote Franklin, "with the vessels under your command, to the west of Ireland and establish your cruise on the Orcades (Orkneys), the Cape of Derneus, and the Dogger Bank, in order to take the enemy's property in those seasÖ About the 15th of August, when you shall have sufficiently cruised in those seas, you are to make route for the Texel, where you will meet my further order." This was commerce-destroying, pure and simple; but Jones's general views were so far realized that it was done by a fairly powerful squadron, and directed finally against the British homeward-bound merchant-fleet from the Baltic, upon which, as laden chiefly with important naval stores, the working efficiency of the British Navy greatly depended. It was hinted to Jones, also, that the ultimate object of going to the Texel was to get out the Indien, the frigate promised him before he left the United States.

During the detention at Groix, which was prolonged by unavoidable repairs upon. the Bonhomme Richard, 119 exchanged American prisoners, seamen, arrived at Nantes. From them, and from foreigners, Jones appears to have completed his crews; and at the same time he weeded out some incapables. On the 11th of August, three days before his final sailing, he reported to Sartine that there were on board the Richard "380 officers, men, and boys, inclusive of 137 marines." Exclusive of marines, therefore, the seaman force, including all that could therein be comprised by stretching the denomination to the utmost, would be 243, when the cruise began. An official but seemingly imperfect roll, which Sherburne quotes in his "Life of John Paul Jones," without stating his reference, gives 227 names of persons constructively on board at the time of the battle of September 23d. This omits two French officers, De Chamillard and Weibert, whom Jones mentions by name in his report of the fight, nor does it give any list of the marines, who probably were in great part, if not altogether, French soldiers. Not more than a half dozen French names appear among the 227, although Jones expressly says that American seamen under Dale, and French volunteers under Weibert, fought the main battery. Assuming the marines to be not materially fewer than at sailing -- for they were not liable to be sent in prizes -- the number on board in the action, 227 + 137, would be 364. From these are to be deducted an officer, 12 seaman, and 4 marines, separated from the ship off Cape Clear by an incident hereafter to be related, and one officer and 16 seamen, similarly separated on the very day of the encounter with the Serapis. These 34, being absent on duty, would remain on the books as present and entitled to prize-money; and the names of the officers are consequently found among the 227. We thus reach 330 as an approximate maximum on board at the time of the action. Allowances for deaths and men sent in prizes would reduce the total probably to little more than 300.

In this remarkable cruise and battle, the composition of the Bonhomme Richard's crew is more interesting than its number. The birthplaces of 207, of the 227 officers and men, is given in the roll. It was as follows: Officers, American-born, 24; French, 2; British, including Jones himself, 6. Seamen, American-born, 55; British-born, including 16 Irish, 77; all other nationalities, 43, of whom more than half, 28, were Portuguese. Add to these 137 French, as marines, and the cosmopolitan character of the ship's company is sufficiently apparent to have satisfied even Jones's wide sympathies as a citizen of the world. He was, however, already somewhat sickening of that character, though he repeats the phrase afterward. The French Navy had not shown toward him a cosmopolitan warmth of appreciation; the tergiversation of the ministry had wearied him; and the common run of mankind, the materials with which he worked, were, as he had said before, more bent on profit than on glory or public advantage. "You will observe with pleasure," he wrote three months later to Robert Morris, "that my connection with a court is at an end, and that my prospect of returning to America approaches. The great seem only to wish to be concerned with tools who dare not speak nor write truth. I am not sorry that my connection with them is at an end. In the course of that connection I ran ten chances of ruin and dishonor to one of reputation; and all the honors and profit that France could bestow would not tempt me again to undertake the same service, with an armament equally ill-composed and with powers equally limited. It affords me the most exalted pleasure to reflect that, when I return to America, I can say that I have served in Europe at my own expense, and without the fee or reward of a court. I shall hope hereafter to be usefully employed under the immediate direction of Congress." In later years he boasted that he had twice declined the offer of a captain's commission in the French Navy, which, as a citizen of the world, he might consistently have accepted from a nation fighting in the same cause. "I can never," he said, at a somewhat later date, "renounce the glorious title of a citizen of the United States."

Before quitting this subject of

nationalities, it may be well to note that the crew of the

Alliance was composed of English and Americans; the former in so

great proportion that her suspicious conduct in the subsequent

action was attributed on board the Bonhomme Richard to a revolt

among her men. Before the ship left Boston, in the preceding

January, it had been found that the dislike of New England

seamen to serving under a French captain was so great that her

complement could not be raised -- a characteristic evidence of

the prejudice still remaining from the colonial wars. To meet

the exigency, there were enlisted a number of men wrecked in the

British sixty-four, the Somerset; also some volunteers among

prisoners of war. With these, and with a few French seamen, a

crew was formed; but it is scarcely surprising to learn that

with such a personnel, and with a half-crazy captain, a mutiny

was organized on the voyage to Europe, to take away the ship

from her officers, and was only suppressed by the resolution of

the latter, sword in hand. The officers and crews of the Pallas

and Vengeance were French subjects.

SECOND PAPER

On the 14th of August Jones's squadron sailed a second time from Groix Roads, for the cruise since so celebrated. Besides the five vessels under the American flag -- the Bonhomme Richard, Alliance, Pallas, Vengeance, and Cerf - it was joined now by two French privateers. On the 23d, having taken two prizes on the way, it sighted Cape Clear and the southwest coast of Ireland. That afternoon, the Bonhomme Richard being close inshore and becalmed, with the flood tide setting her into a dangerous bay, the barge was sent ahead to tow her out; the ordinary boats being then in chase of a strange sail. Taking advantage of these conditions, the men in the barge cut the tow-rope and pulled to the shore. They were at once followed by another boat with an officer -- the master -- and four marines; but the chase leading far, and a fog setting in, both pursuers and pursued were lost to the ship, and landed in Ireland. Jones was thus deprived of two officers and twenty-four men; probably, from the circumstances, among the most enterprising and capable. The incident led to a stormy interview between Jones and Landais, in which the latter took occasion, not only to blame his superior, but to assert his own right to independence of action, as "the only American in the squadron." It seems a pity that Jones did not at once put him under arrest, and send his capable first lieutenant, Dale, to command the Alliance; but he was hampered by the "Concordat," short also of officers of mature years, and had besides just lost the master. Poor as she was, the Bonhomme Richard was the efficient backbone of the squadron, under his own sure control, and therefore not to be weakened; but the whole affair, from first to last, serves to illustrate the radical nature of the difficulties Jones had to contend against, and thereby to exhibit his personal ascendancy of character, which wrung success out of conditions that would not have been experienced by the commander of a more regular force.

On this occasion Landais showed also the petulant timidity of temperament, which probably was the real cause of his miserable conduct in the time of action. If they "continued in that station three days longer," he complained, "the squadron would be taken." This was not his responsibility, but that of Jones; and the latter intended to remain there for a week or ten days, because favorably placed for intercepting the enemy's trade. Nevertheless, two days later, on the evening of the 26th of August, a southwest gale coming on, he quitted the place and proceeded northward. In this, "I declare," he said in his official report, "that I did not follow my own judgment, but was led by the assertion of Captain Landais." "To his fears and remonstrances on the coast of Ireland," he wrote again, two months afterward, "is owing the escape of eight East India ships that arrived at Limerick three days after I had gratified him by leaving sight of the entrance of that harbor." In measure, however, Jones here condemns himself; and an admission of his a few weeks later, in reference to a particular project, not specified, reveals a strain of weakness in his motives. "Nothing prevented me from pursuing my designs but the reproach that would have been cast upon my character as a man of prudence, had the enterprise miscarried. It would have been said, 'Was he not forewarned by Captain Cottineau and others?'" The subordination of public enterprise to considerations of personal consequences, even to reputation, is a declension from the noblest standard in a public man. Not life only, but personal credit, is to be freely risked for the attainment of public ends.

At or about the time of the gale of the 26th, the two privateers and the Cerf parted company and never rejoined. The diminished squadron proceeded north on its appointed course, and for the appointed rendezvous. On the 4th of September it passed Fair Isle, between the Orkneys and the Shetlands, and entered the North Sea. Nothing of particular interest occurred, beyond the capture of prizes and renewed instances of insubordination by Landais, who, after disappearing once or twice, parted company on the night of September 6th and did not rejoin until the morning of the 23d. On the 13th the Cheviot Hills, between Scotland and England, were sighted. Being now off the Firth of Forth, Jones projected entering it, to seize the shipping at Leith and lay the town under contribution. The wind being favorable, he would, if alone, have proceeded at once to do so; but having the Pallas and Vengeance in sight, he felt compelled to concentrate his force for the enterprise. Time was lost in recalling them, and more in council, "in pointed remarks and sage deliberation." "I do not think," Jones wrote to Lafayette, "that the desire of glory was the uppermost sentiment in the breast of any captain under my command, at the time we left L'Orient." Next day, the 15th, the wind came contrary. The three vessels nevertheless continued to beat in until the morning of the 17th, when, being nearly within cannon-shot of the town, the wind increased to a gale, and forced them out. The attempt was then abandoned, and the squadron steered south.

Jones was now in a situation that intercepted the colliers between London and North Britain, upon which the capital depended for its coal supplies. Several of these were destroyed; and he was also favorably placed for menacing the Baltic trade. At the same time the position was one of great danger, for the alarm had been given, and it was not to be doubted that the Admiralty would speedily concentrate in that quarter a greatly superior force. It was now Captain Cottineau, of the Pallas, who urged an instant departure, and Jones heard afterward that he had announced his intention of leaving the coast, if the Richard, which had dropped out of sight while repairing a topmast, did not join next day. It was Jones's good fortune that the opportunity of his life was already hastening across the North Sea, and now close at hand; it was his merit that he seized it, and immortalized his name.

On the 21st of September the three vessels were off Flamborough Head, a bold promontory and natural landmark, jutting far into the sea from the eastern coast of England, which here trends north-northwest and south-southeast. As such a projecting point necessarily forces coasters off their direct course, they always tend to pass close to it, and it is therefore a specially good position for a commerce-destroyer. Immediately south of the Head is Bridington Bay, and thirty miles farther on Spurn Head, at the mouth of the Humber. Twenty miles to the northward of Flamborough Head lies the town of Scarborough, also on the coast. An extract here from Jones's report of his proceedings will convey an idea of the injury threatened to British trade. Having "taken and sunk a brigantine collier belonging to Scarborough, a fleet appeared to the southward; it was so late that day that I could not come up with the fleet before night; at length, however, I got so near one of them as to force her to run ashore, between Flamborough Head and the Spurn. Soon after I took another, a brigantine from Holland, belonging to Sunderland; and at daylight next morning (September 22d), seeing a fleet steering toward me from the Spurn, I imagined them to be a convoy, bound from London for Leith, which had been for some time expected. They had not, however, courage to come on, but kept back, except one which seemed to be armed, and that one also kept to windward [the wind was southwest] very near the land, and on the edge of dangerous shoals which I could not with safety approach." This fleet put back, notwithstanding that Jones hoisted a British private signal, obtained from a pilot who had taken the Richard for a British ship. He then steered north to rejoin the Pallas, which had been cruising in that quarter, and at 3 a.m. of the 23d found her, in company with the long missing Alliance.

At dawn the business of overhauling passing vessels was resumed, but the day was to close upon a more stirring scene. Having just chased a brigantine to windward [southwest], a large ship was seen, about noon, rounding Flamborough Head from the north. Jones then sent a boat in pursuit of the brigantine, and turned the Richard's bows toward the new-comer. While standing this way a fleet of forty-one sail appeared off the Head, bearing north-northeast from the Richard, which therefore evidently was close in shore. The single ship had now anchored in Bridlington Bay; but Jones forsook this smaller prey for the larger, and, making signal for a general chase, stood toward the fleet.

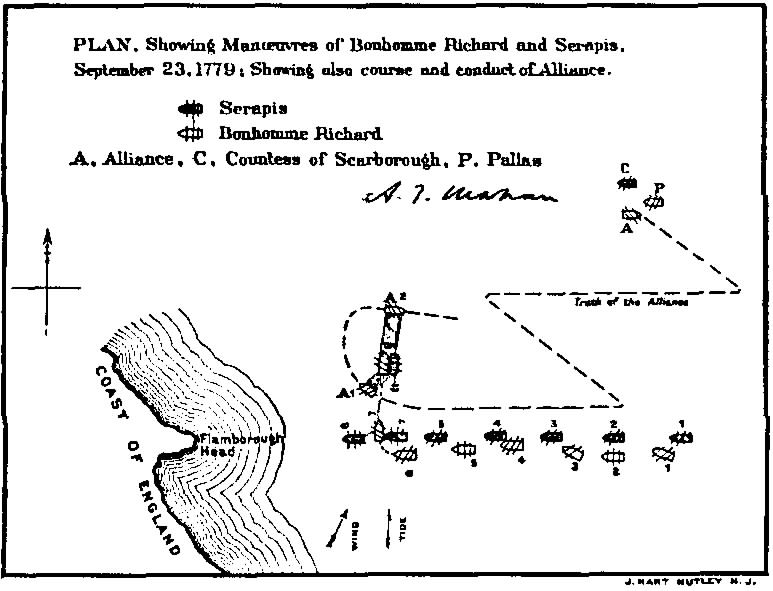

The latter was a body of merchantmen from the Baltic, under convoy of the Serapis, 44-gun ship, Captain Richard Pearson, and of the Countess of Scarborough, a vessel of twenty guns. At four o'clock that morning, being then close in with Scarborough, Pearson had been informed by a boat from shore that a hostile squadron was on the coast. He immediately signalled the convoy to bear down under his lee -- that is, to get north of him, the wind being south-southwest -- and allow him to be between them and the enemy; but they, "behaving," to use Nelson's words about a Baltic convoy two years later, "shamefully ill, as all convoys that ever I saw did," replied by making all sail and standing on southeast, to double the Head. At noon, however, they got sight of the American vessels. "They then tacked," wrote Pearson, "and made the best of their way under the shore for Scarborough, etc., letting fly their topgallant-sheets, and firing guns," in token of danger. The Serapis continued southeast until 4 p.m., when she had Joness ships in plain sight from the deck. Being now far enough to windward to be sure of covering his charge, Pearson hove-to (stopped) to allow the Scarborough to come up from the northward, while Jones continued to approach from the south. At 5.30 p.m. the Scarborough had joined, and at six o'clock the Serapis went about and steered west, on the wind on the port tack, "in order to keep our ground better between the enemy's ships and the convoy." She was on this course when the action opened, the Scarborough following at a little distance in her wake. As the United States ships kept their bows "end-on" toward him, Pearson was unable to count their guns, or to estimate their force accurately.

The detailed description of the Bonhomme Richard has been deferred to this point, in order to present her in close connection with her adversary and her battle. As before said, she was an old Indiaman, with exceedingly high poop. Her principal battery was composed of twenty-eight 12-pounders on a single deck, fourteen on each side. On the deck above these were eight 9-pounders. This was her proper force, and actually that with which she fought; but to increase it, as far as he could, Jones had cut three ports aft, on each side, near the water-line, on the deck below the principal battery. In these ports were mounted six 18-pounders. The ship had therefore in all 42 guns, 21 on a side, which discharged a total weight of 258 pounds.

The Serapis was classed as a 44-gun ship on two decks; that is on two covered decks. On the lower gun-deck she had twenty 18-pounders; on the deck above it, the upper gun-deck, twenty 9-pounders; and on the uncovered deck above that, ten 6-pounders. Total, 50 guns, 25 on a side, throwing together 300 pounds. The mere total weight of a single broadside is not the only factor to be considered; the penetration power of 18-pounder guns being singly much greater than that of 12-pounders.

Jones had ordered his vessels to form line, for mutual support; but Landais, whose post was astern of the Richard, stood on disregardfully with his greater speed, until he could make out the force of the stranger. Then he hauled up, out of gunshot to windward, and so remained until after the battle began. He had already hailed Captain Cottineau of the Pallas, saying that if the enemy had a ship of more than fifty guns there was nothing to do but to run away; the particular demerit of which remark is not so much in the opinion itself, as in the fretful, unofficerlike insubordination, which alone could have induced a junior to utter such an opinion in the hearing of two ships' companies. The question of running was not for his decision, but for Jones.

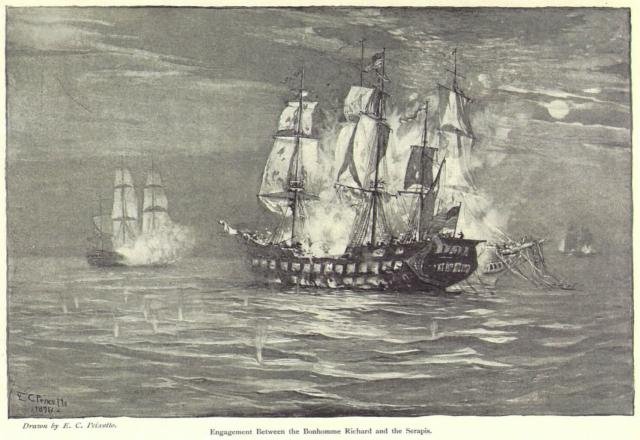

Although steering nearly before the wind, the Richard was so slow that she did not come within range until 7 p.m., when, it being already after dark, she rounded-to - i.e. turned her side to the wind, parallel to her opponent -- on the port bow of the Serapis, within pistol-shot[.] Pearson's delay to fire during the critical last moments of approach may probably have been due to a lingering doubt as to the stranger's character. He now hailed: "What ship is that?" The answer was understood by him to be: "The Princess Royal;" but a shot soon following, the antagonists exchanged broadsides, and the battle began. Two of the three 18-pounders on that side of the Richard burst at the first volley, killing and wounding most of their people, and blowing up the deck above. Only eight 18-pound shot were fired by her during the engagement. After each ship had discharged two or three times the guns of the batteries engaged -- the port, or left hand one of the Serapis, and the starboard of the Richard -- Jones threw his sails aback, that the Richard might drop slowly astern. (2) As the Serapis was advancing, this caused the American ship to pass along the side of her opponent, at a distance of eighty to a hundred feet, both firing continuously. Jones's object was to get a little in the rear of the Serapis, so that, by filling his sails again, he could come up on her, and by using the helm run alongside, rush his men on her decks, and carry her by a charge. Being of inferior battery force, but with an unusual number of soldiers, close fighting, hand to hand if possible, was imperative. The same attempt could have been made from his first position, by crossing the bows of the Serapis, but was less certain. Accordingly, when he found himself a little astern, he again went ahead, (3) and ran on board "upon the Serapis's weather-quarter" -- to use Pearson's words; or, as the American lieutenant, Dale, says, ran her bows into the stern of the Serapis. (4) The attempt to board from such a position was too disadvantageous, and was easily checked by the British. To board succesfully, numbers being still nearly equal, the attacking ship should either be along-side, able thereby to throw her men in force on one part of the long line the enemy has to defend; or else, lying across her opponent's bows, where the raking fire of her guns, and the others powerlessness to reply, support her boarders. After a ship has been well whipped, she can be boarded with less caution.

Jones ascribed this failure, and others to which he alludes, to the unmanageableness of the Richard, cumbersome at best, and now with rigging shot away. Her sails being again backed, she dropped clear, (5) filled once more, and stood ahead, still for the port side of the enemy. Pearson on his part, fearing to be raked from astern, now threw his sails aback, to come once more abreast of the Richard. Thus, one moving slowly forward and the other backward, (6) the American ship drew again ahead. As she did so, her helm was put over, and the Richard crossed the bow of the Serapis, from left to right (6,7). Jones's intention, to use his own words, was "to lay the Bonhomme Richard athwart the enemy's bow;" that is, to place her in such wise that, when the collision occurred, the bow of the Serapis would be at the middle of the Richard's length, the two perpendicular to each other. In this case the American guns would fire from end to end of the British ship, which could not then reply. Here again he was partially foiled, because the Richard, owing to her braces being shot away, did not work promptly; and partly, perhaps, because he did not clearly perceive that the Serapis was going astern. Instead, therefore, of touching at mid-length near the mainmast, the Richard, as she fell on board the Serapis, caught the jib-boom of the latter in her own mizzen-rigging. (7) Then the wind, pressing on the sails of the Serapis as she was held fast forward, turned her stern round to the right, and the vessels swung alongside, the bow of the Serapis abreast the stern of the Richard, the starboard sides of the two touching nearly throughout their length.

As Jones wished such close action, he at once busied himself lashing the ships together. Pearson, on the contrary, having much the heavier guns, wanted to get away, to regain that great advantage. He therefore let go an anchor from the port side -- opposite from the Richard -- trusting that, the Serapis being thereby held fast, the American vessel would be wrenched away before realizing the situation. Here, however, he was the one deceived. The two vessels, riding to the one anchor, swung together to the tide, an indication of the slackness of the wind. (8) As the tidal current was then setting to the northward, toward Scarborough, the bow of the Serapis and the stern of the Richard pointed to the southward; a condition necessary to be noted, to comprehend the subsequent movements of the Alliance.

It was now eight o'clock. Henceforward -- to use Nelson's words about his own most. desperate action - "there was no manúuvring, there was only downright fighting;" and great as was Jones's unquestionable merit as a handler of ships, it was downright fighting endurance, of the most extreme and individual character, that won this battle. When thus in contact, the superiority of the British eighteens over the American twelves, though less than at a distance, was still great; but a far heavier disparity lay in the fabrics of the two enemies. The Richard was a very old ship, rotten, never meant for naval use; the Serapis was new, on her first commission. The fight hitherto having engaged the port guns of the latter, the starboard lower gun-ports were still closed, and from the ships' touching could not be opened. They were therefore blown off, and the fight went on. "A novelty in naval combats was now presented to many witnesses, but to few admirers," quaintly wrote Lieutenant Dale, who was in the midst of the scene below decks. "The rammers were run into the respective ships to enable the men to load;" that is, the staves of the rammers of one ship entered the ports of the other as the guns were being loaded. "We became so close fore and aft," reported Pearson, "that the muzzles of our guns touched each other's sides;" and even so, by the testimony of the lieutenant on the lower gun-deck of the Serapis, her guns could not be fully run out, owing to the nearness of the vessels.

The gradual process of demolition on board the Richard has not been traced, but the total result has been recorded. "With respect to the situation of the Bonhomme Richard," says Jones's report, "the rudder was cut entirely off the stern frame, and the transoms were almost entirely cut away. The timbers by the lower deck especially, from the mainmast to the stern, being greatly decayed with age, were mangled beyond my power of description." "On my going on board the Bonhomme Richard," wrote Pearson, "I found her to be in the greatest distress; her counters and quarters entirely drove in, and the whole of her lower-deck guns dismounted; she was also on fire in two places, and six or seven feet of water in her hold." In short, the two sides of the Richard, from the mainmast aft, were practically gone. She had also several shot-holes below water, and Jones states that toward the end of the battle the shot of the Serapis ranged over her lower decks, and passed to the sea beyond, meeting no side to resist them.

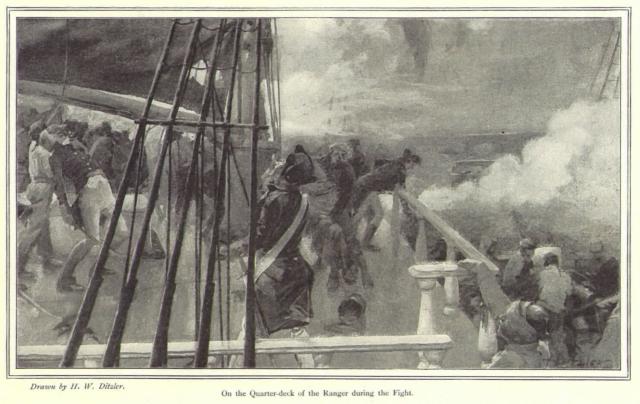

The decisive factor in this really tremendous exhibition of human energy and fury, was that the Richard, hopelessly overpowered in the battery, had superior force above decks and aloft -- in the tops. This reproduced essentially the conditions of the famous duel between the Victory and the Redoutable, in which Nelson fell. Jones states expressly that "the battery of 12-pounders, on which I placed my main dependence, was entirely silenced; not one of the heavier cannon was fired during the rest of the action." It seems difficult to reconcile this with the tenor of Dale's account, but the latter is not absolutely explicit on the point. It is clear, however, that the Serapis's gunners must in great measure have kept those of the Richard under, and the fact accounts for their unremitting fire. Her lower guns, by the evidence of their officer, fired two shot at each discharge. "I had only two pieces, 9-pounders," continues Jones, "on the quarter-deck, that were not silenced." The officer in charge of them being desperately wounded, Jones had to take his place. One deck officer had been lost off Ireland; and the one sent away that morning had, to his discredit, failed to return. One lieutenant, one sailing-master, and a lot of raw midshipmen, constituted Jones's sea-officers on this occasion, which again illustrates his personal force. One more 9-pounder was with difficulty brought over from the other side of the deck, and these three guns maintained the fight; mightily seconded, however, by the musketry from the tops. One of the three was aimed continuously, with double-headed shot, against the mainmast of the Serapis, which broke short off at the deck, and fell, just as that ship struck. The other two were directed to clearing the enemy's deck, in which was the one remaining chance of victory. "The enemy were unable to stand the deck," reported Jones, "but the fire of their cannon was incessant;" and the British on the gun decks probably did not realize at all any possibility of defeat from their silent opponent.

Under these conditions the fight went on. The Richard was already leaking heavily when the ships came together, and one of the pumps also had been shot away. The carpenter, finding the water gaining, expressed the fear, somewhere between nine and ten o'clock, that the ship would sink; and one of the under-officers, a gunner, becoming frightened, ran to the flagstaff to haul down the colors. Fortunately, the staff had already been shot away, so that he was reduced to shouting for quarter. This cry Pearson heard, and called to know whether his opponent had struck. Receiving no answer, for Jones had hurled his boarding-pistols at the clamorer's head, breaking his skull and silencing his yells, he ordered his men to board; but as they attempted to do so, they found a superior force gathered to oppose them, and retired. By this time, indeed, Jones had established his predominance above decks; the British seamen having been so driven out of their own tops that the Americans went back and forth to them by means of the entangled yards and rigging. Here, however, a new trouble arose. In the midst of the confusion, the panic of the gunner and the carpenter reached the master-at-arms, in charge of the British prisoners on board, between two hundred and three hundred in number. The Richard was on fire also in various places, "a scene dreadful beyond the reach of language," says Jones; and Dale notes that he had continually to take men from the guns to extinguish the flames, at times close to the magazine. Supposing the ship doomed to speedy destruction, by fire or water, or both, the master-at-arms released the prisoners, who came swarming on deck; an act of treachery, Jones thought, but this does not necessarily follow, and the man, though put in irons next day for this fault, was afterward employed again by Jones in the same capacity. It is a prescribed duty of a master-at-arms to release prisoners in a moment of emergency, though to do so on so large a scale, without express orders, on a doubtful rumor, certainly shows lack of head. Fortunately, the prisoners also were badly frightened, wholly disorganized, of course, and in utter ignorance of the state of things. Dale consequently, with much presence of mind, put them to pumping, where they worked for dear life, taking no time to think of aught else. The Richard's men at the pumps were thus enabled to join the fight. One prisoner, however, a ship captain, took a cooler look, and, it is said, passed over to the Serapis to tell Pearson that the Richard was beaten, if he only held on.

But Pearson also had his difficulties. "From eight to ten," he reports, "from the great quantity and variety of combustible matters which they threw upon our decks, chains, and in short, into every part of the ship, we were on fire no less than ten or twelve times in different parts of the ship, and it was with the greatest difficulty and exertion at times that we were able to get it extinguished." The first lieutenant of the Serapis testified that the starboard side, the one engaged, was all in a blaze, including parts of the rigging. The silencing of the British above-deck fire left the topmen of the Richard a comparative impunity in throwing grenades, which resulted at last in an incident that definitely turned the fight. A quantity of cartridges had been permitted to accumulate on the Serapis's lower decks, and upon one of these a hand grenade fell. A terrific explosion followed, running from cartridge to cartridge, from the mainmast aft, blowing up all the men and officers there stationed, and rendering useless the five after guns. A number of men jumped overboard, probably because their clothes were on fire; among them being the lieutenant of the lower deck, who was badly scorched.

Pearson, who was a gallant fellow, continued to fight for nearly an hour longer; but a crew that has suffered thus from an internal catastrophe experiences a loss of confidence, of moral force, far greater than those who, like the Richard's men, had undergone only the punishment naturally to be expected from the external enemy. The bursting of the 18-pounders, was, it is true, of a like character, but narrowly localized; it paralyzed efficiency at the particular point, but through the rest of the ship the spirit of Jones and of Dale yet reigned unabated. Under the conditions, the next important incident, although it bore more heavily upon the Richard, which was also in far worse material condition than the Serapis, affected the British, through their commander, more than it did the Americans, and decided their submission. This was the final appearance of the Alliance upon the scene.

By a weight of testimony, which cannot be gainsaid, it appears that shortly after the two chief contestants grappled, the Alliance passed athwart the line on which they were lying anchored, and fired crossbar and grape-shot; raking them at such a distance that the inevitable scattering of the projectiles threw a large proportion into the Richard. Two men were killed, and many ran from their quarters, crying, "The Alliance is manned with English men, and firing upon us." She then sailed away, and stood down to the Countess of Scarborough and the Pallas, which were lying some distance to leeward -- north or northeast -- of the Richard and Serapis; the Scarborough having struck to her superior opponent, after an hour's engagement (Plan, see P. A.). Landais spoke the Pallas, and then returned toward the other vessels. To do this he had to make some tacks, both wind and tide being contrary. At about ten o'clock he passed to windward -- southward- -- of the two; crossing first the bow of the Serapis, which lay to seaward, and then the stern of the Richard. As he drew upon the port -- inshore -- quarter of the latter, he fired a broadside, part of which the Serapis may have got, but most of it entered the Richard.(A1) As she was approaching, Jones had had the private signals shown on the port side of his ship; but it was, besides, bright moonlight, the moon being at full, and passing the meridian at about eleven, therefore shining from behind the Alliance toward the combatants, in the most favorable position to distinguish the latter, which differed in form and color. Despite all these circumstances, Landais, after running along the Richard's port side at some distance, kept away, with the wind well on the quarter, passed north of the two vessels, across the Richard's bow, again at a great distance (A2), and again fired a broadside, which struck both ships.

It is not, perhaps, very material to the sufferer in such a case, whether the guilty party is treacherous or merely incapable; the result is the same. Jones and his officers doubtless believed the worst of Landais's motives; and it may be assumed that almost any person who had undergone such an experience would have thought the same, especially in view of his previous record of talk and action. As he held an American commission only, it was impracticable, with the few officers of rank then in Europe, to bring him to a court-martial; and the matter therefore was never thoroughly sifted by sworn evidence and cross-examination on both sides. In default of such decision, Jones, by the advice of Benjamin Franklin, caused a paper to be drawn up, embodying, under twenty-five heads, the instances of insubordination and incapacity shown by the captain of the Alliance during this cruise. Each particular was attested by a number of officers of the squadron, including, in several cases, some of Landais's compatriots. It was thus placed beyond all reasonable doubt that the man was not only unfit by temper and professional ability to command a ship, but that he was also of that excessive timidity which grows petulant, fractious, and querulous in the face of danger, under the strain of apprehension.