(With extracts from unpublished letters by him)

Molly Elliot Seawell.

The Century 49:6 (April 1895) 873-894.

["]TRAITOR, if you will, was Monsieur John Paul Jones, afterward Knight of His Most Christian Majesty's Order of Merit -- but a braver traitor never wore sword." Such were almost the last words traced by the hand of Thackeray, and they show the astonishing misconception of Paul Jones which prevailed in the mind of one of the justest men that ever lived. Washington was a hero even to his enemies; yet Washington had actually held a commission in the British army, while Paul Jones could say proudly to the American Congress at the close of the war: "I have never borne arms under any but the American flag, nor have I ever borne or acted under any commission but that of the Congress of America." This singular distinction against Paul Jones extended to the whole of the feeble naval force of the colonies. Soldiers were treated from the beginning as prisoners of war, while until Paul Jones forced an exchange of prisoners upon equal terms, American sailors were formally declared to be "traitors, pirates and felons." Let this "traitor, pirate and felon" enumerate his services in his own words:

In 1775 J. Paul Jones armed and

embarked in the first American ship of war. In the Revolution he

had twenty-three battles and solemn rencountres by sea; made

seven descents in Britain and her Colonies; took of her navy two

ships of equal, and two of far superior force, many store ships

and others; constrained her to fortify her ports; suffer the

Irish volunteers; desist from her cruel burnings in America, and

exchange as prisoners of war, the American citizens taken on the

ocean, and cast into prisons in England as traitors, pirates and

felons!

In his perilous situation in Holland his conduct drew the Dutch into the war, and eventually abridged the Revolution. He received from Louis XVI. the Order of Military Merit and a gold sword June 28, 1780. Congress bestowed on him the following honors: The thanks of the United States, April 14, 1781; election as first officer of the navy, June 26, 1781; a gold medal October 16, 1787. This last favor was granted to only six officers: 1st, General Washington, the commander-in-chief, for the taking of Boston. 2nd, General Gates, for taking the army of Burgoyne. 3rd, General Wayne, for taking Rocky Point, of which the garrison was much stronger than the assailants. 4th, General Morgan, for having cut down and destroyed eleven hundred officers and soldiers of the best troops of England, with nine hundred men, solely militia. 5th, General Green, for having gained a decisive victory over the enemy at Eutaw Springs.

But all these medals, although well merited, were given in moments of enthusiasm. He had the satisfaction solely to receive the same honor, by the unanimous voice of the United States assembled in Congress, the 16th of October, 1787, in memory of services which he had rendered eight years before.

To these distinctions may be added a letter from the Congress of the United States, in 1787, publicly and officially recommending Paul Jones to the King of France -- one of the greatest honors ever paid a citizen; a commission, which arrived a few days after Paul Jones's death, appointing him the representative of the United States to treat with the Dey of Algiers concerning the release of the American captives in Algeria; an act of Congress, June 30, 1834, appropriating fifty thousand dollars for the beginning of a first-class frigate to be called the Paul Jones; an order from the Navy Department, January 30, 1851, directing that the frigate St. Lawrence bring to the United States the body of Paul Jones; and a gift by Congress of fifty thousand dollars to the heirs of Paul Jones, July 6, 1848.

From Russia he received, by permission of "his sovereign," as he quaintly calls the government of the United States, a commission as rear-admiral in the Russian navy (subject, however, to the pleasure of the United States), and the ribbon of St. Anne, bestowed upon him by the Empress Catherine.

Thus, in America he was the ranking officer of the United States navy; in France he was a chevalier of the Most Noble Order of Military Merit; in Russia he was a rear-admiral; while in Great Britain he was a "traitor, pirate and felon," with a price of ten thousand guineas put upon his head; and at one time there were forty-two ships of the line and frigates scouring the seas for him.

The act of Congress concerning the building and naming of a first-class frigate after Paul Jones singularly lapsed.

The St. Lawrence went upon her patriotic errand to bring the ashes of Paul Jones to America; but, according to the custom in Paris, some years after his death, his bones, which lay in an old cemetery near the Barrière du Combat, were destroyed by quicklime.

Besides Thackeray in England, Cooper in America and Halévy and Dumas in France have taken Paul Jones as a hero of splendid romance. He was a true as well as a romantic hero, however. If Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Lafayette, Adams, and Morris are to be believed, he was a man of lofty character and true patriotism.

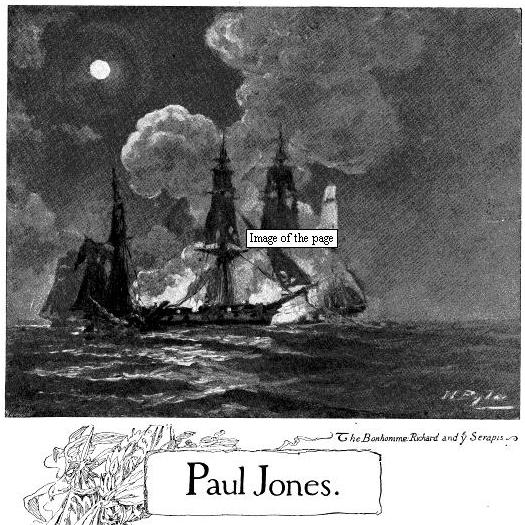

The two war-ships taken by Paul Jones

were scarcely felt by mighty England, with her six hundred

fighting ships. But the wound to the honor of the greatest and

proudest of nations was deeply felt, and was earnestly sought to

be avenged. In a feeble ship he twice cruised up and down the

narrow seas of the greatest naval power on earth, raising her

coasts as had not been done since the days of the Spanish

Armada, threatening her northern capital, landing whenever and

wherever he liked, burning her shipping, and capturing the only

two war-ships that came within hail of him -- ships manned by

the hardy sailors of the Mistress of the Seas. Until then

England had made good her proud boast:

And not a sail but by permission

spreads.

After Paul Jones hoisted his flag this boast was no longer good.

The son of John Paul, a poor Scotch gardener, John Paul Jones was born at Arbigland, in Kirkcudbrightshire, on July 6, 1747. The reasons for his adoption of the name of Jones have never been explained. That he did not wish to sink his identity is shown by his retention of his original name. In his earlier career he signed himself "John Paul Jones." Afterward he signed himself "J. Paul Jones"; but when he became the hero of Paris and Versailles, and Europe resounded with his fame, his cards read simply "Paul Jones." This gradual emancipation from the self-made man's fondness for titles and dignities is strikingly shown in his will, where, after a lifelong struggle for honors and precedence, during which he contended for them in a manner at once fierce nnd childish, on the day of his death he described himself only as "John Paul Jones, a citizen of the United States."

There is no record of his having attended any school except that of the parish of Kirkbean; but he developed a truly Scotch passion for reading and writing. He went to sea when twelve years old, and made two voyages, during his minority, in a slaver; but, hating the traffic, he left it and the ship too. At twenty he was in command of a fine brigantine. About this time occurred what he calls, in a letter to Robert Morris, "a great misfortune," adding: "I am under no concern whatever that this, or any other circumstance of my past life, will sink me in your opinion." The trouble was a threatened criminal prosecution for having had a carpenter flogged -- which was the usual mode of punishment in those days. The matter was investigated, and Paul Jones was fully acquitted. It is worthy of remark that the magistrate who inquired into that matter notes that Paul Jones expressed great sorrow for having had the man flogged, although the charge of cruelty was fully disproved. He returned to Scotland once after this, and although affectionately received by his own family, his friends and neighbors seem to have treated him coldly. The smart from this injustice turned the indifference he felt for his native land into hatred, and ever after he considered himself quite free from any responsibility for having been born and having spent the first twelve years of his life in so inhospitable a country.

In his twenty-seventh year a great and fortunate change occurred to him. His brother William, who had emigrated to Virginia and died there, left him an estate. There is no doubt that Paul Jones was often afterward in want of ready money; but it must be remembered that everybody was in want of ready money in the eighteenth century. Certain it is, from his papers preserved at Washington, that he might be considered at the beginning of the war a man of independent fortune. The two years of his life in Virginia are obscure, as might be expected from a man living the life of a provincial country gentleman, which the records concerning him prove. At the outbreak of war with the mother country, Paul Jones hastened to Philadelphia, and through Mr. Joseph Hewes, a member of Congress from North Carolina, got his commission as senior first lieutenant in the infant navy of the colonies. It was then he made the acquaintance of Robert Morris, to whom he felt a passionate gratitude and affection, and whom he named as sole executor in his will, Mr. Hewes being then dead.

On December 22, 1775, was made the beginning of the American navy; and from this point the true history of Paul Jones begins. He was then twenty-eight years old, of the middle height, his figure slight, but graceful, and of a dashing and officer-like appearance. His complexion was dark and weather-beaten; his black eyes very expressive, but melancholy. His manners were easy and dignified with the great, and he was without doubt fascinating to women. He often fancied himself in love, and, like Washington, sometimes even wrote bad verses to ladies; but it is unlikely that any woman ever had the real mastery of his heart. He was not deterred by the greatness of "the Fair," as he called them when they pleased him, and made love to very great ladies quite as boldly as when with the wretched Bon Homme Richard he laid aboard the stout Serapis. He had a peculiarly persuasive way with sailors as with women; and if he wished to enlist a sailor would walk up and down the pier with him by the hour, and he never failed to get his man. He was a tireless letter-writer, and when Paul Jones wrote as Paul Jones spoke, nothing could exceed the force and simplicity of his style. But he was subject to attacks of the literary devil, and his productions then were intolerably fine. He wrote and spoke French respectably, and his handwriting, grammar, and spelling are all much above the average of his day.

His first duty was as first lieutenant

of the Alfred, Commodore Hopkins's flag-ship. On this

vessel he hoisted for the first time the original

flag of the Revolution -- the rattlesnake

flag. In a letter to Robert Morris in 1783, Paul Jones

says:

It was my fortune, as the Senior of

the First Lieutenants, to hoist, myself, the Flag of America (I

Choose to do it with my own Hands) the first time it was

displayed. Though this was but a light circumstance, yet, I feel

for it's Honor more than I think I should have felt had it not

so happened.

The services he was engaged in under Commodore Hopkins were far from brilliant. The commodore had a strong disinclination to go "in harm's way, -- to use a favorite expression of Paul Jones, -- and within a year was dismissed the navy. Paul Jones's first command was a little sloop of war, the Providence; and from a memorandum among his papers, in the handwriting of the secretary of the Congress, we learn that his uniform was: "Blue Cloth with Red Lappels, Slash Cuffs Stand up Collar, flat yellow Buttons; Blue Britches, Red Waistcoat with Narrow Lace." The uniform for the junior officers was also prescribed, and all were commanded to wear "Blue Britches." The marine officers, however, were to wear "Britches edged with Green, Black Gaiters and Garters."

PAUL JONES RAISING THE RATTLESNAKE FLAG ON THE "ALFRED."

Paul Jones's conduct during the cruise he made in the Providence, and afterward in command of a small squadron in 1776, won him great credit, especially with Washington. His employment was the conveying of men and stores from Rhode Island to Washington at New York. Long Island Sound swarmed with the cruisers of Lord Howe's fleet, and Paul Jones's address in eluding them, especially the Cerberus frigate, which tracked him for weeks like a bloodhound, marked him as a man of great enterprise. His next cruise with a little squadron maintained his reputation, and from that on the requests of officers who wished to serve under him were frequent. Paul Jones's replies to these are quaint reading. He always protests a disinclination to "entice" officers away from other commanders; but never fails to note the good points of his own ship, and to give a forecast of his daring schemes very captivating to an ambitious young officer.

There was great confusion in the tables of rank first adopted in the navy, and thence proceeded a grievance that Paul Jones never ceased to protest against bitterly, until in 1781, many years afterward, he became, by the unanimous election of Congress, the ranking officer of the American navy. By the personal carelessness of President Hancock, Paul Jones's original commission as captain -- the first commission granted under "the United States" -- was lost. When a new one was given him, he found, to his natural indignation, that thirteen of his juniors were ahead of him on the list of captains. How infuriating this was to a man as greedy of distinction as Paul Jones, may be imagined. He always spelled rank with a capital, and wrote of it as "Rank, which opens the door to Glory." He swore he would never serve under any of the men thus unjustly given precedence of him. Congress, while negligent in doing him justice, was wise enough, nevertheless, to give him always a separate command. It was determined to send him to Europe in the Ranger sloop of war, and in Europe to give him the finest command then at the disposal of the Congress. This was a splendid frigate -- the Indien -- building at Amsterdam. The Ranger was a very inferior ship, poorly equipped in every respect. He was able to get only thirty gallons of rum for his whole ship's company. Cooper, who had himself been a naval officer, bewails and exults over this in the same breath: "Under such difficulties was the independence of this country secured!"

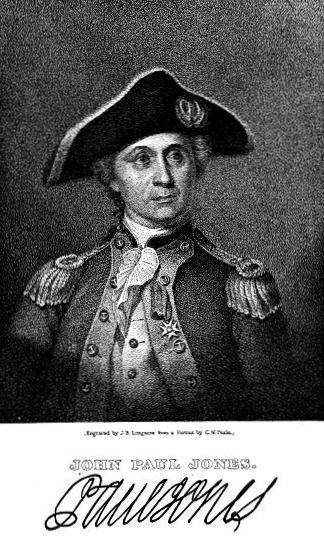

JOHN PAUL JONES

Copperplate engraving by Carl Guttenegra, from a drawing by C.

J. Motté

As Paul Jones had been the first to raise the original flag of the Revolution, so he was the first to raise the Stars and Stripes over a ship of war -- the Ranger. This occurred at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in the autumn of 1777.

The ship was well manned, but poorly officered. The first lieutenant -- Simpson -- was mutinous from the start, and eventually, through the stern determination of Franklin, was dismissed the service. Paul Jones's unwise indulgence to this bad officer is explained in his unpublished correspondence. Simpson was cousin to the Quincys, the Wentworths, the Wendells, and, above all, to President Hancock, who had it in his power to remedy that burning injustice of rank which Paul Jones declared to be "no triffle." Tradition has it that Paul Jones was "strict and sharp in discipline" to the point of once kicking an officer down the hatchway for an insolent word. But there are indications that he had the self-made man's too great respect for those he imagined could do him harm; and his course with regard to Simpson, and especially with his captains during his cruises as commodore, shows an excessive leniency.

On November 1 [14] he sailed for France, being recommended to the American commissioners at Paris by the Marine Committee as "an active and brave commander in our service." Upon his arrival in France, the commissioners invited Paul Jones to come to Paris, and their first news was a cruel disappointment to him. The Amsterdam frigate had become a cause of difficulty between the French and Dutch governments. The court party in Holland was furiously opposed to the American cause, and in order to prevent the confiscation of the frigate it was passed over to the French government, which took upon itself the charge of its completion. It is hard to imagine a more crushing disappointment to a man of Paul Jones's temperament than the loss of this ship. He seems, however, to have borne it with a fair degree of patience.

From the beginning of his acquaintance with Franklin a mutual respect and a deep affection sprung up between them. The wise Franklin saw at a glance what manner of man Paul Jones was, and in one noble sentence described him better than many volumes could: "For Captain Paul Jones ever loved close fighting." In Quiberon Bay there was a great French fleet under the command of Admiral La Motte-Picquet, and from him Paul Jones obtained what he claimed to be the first foreign salute ever given the American flag. It is true that the governor of one of the Dutch West India Islands had got in trouble the year before for saluting the American flag; but La Motte-Picquet's was undoubtedly the first direct and unqualified salute. It was not obtained without some address as well as boldness on Paul Jones's part, as the alliance between France and the United States was not then signed; but when the French admiral agreed to salute, he did it courteously, paying the compliment of having his guns already manned when Paul Jones sailed through the fleet.

And now, for the first time in his life, he had the opportunity of studying the theory and technic of his profession on a large scale. Admiral La Motte-Picquet, Admiral Count d'Orvilliers, and especially the chief of staff, the Chevalier du Pavillion, were accomplished tacticians. True it is, their tactics had rarely been able to withstand more than a few broadsides from the unscientific English; but Paul Jones not only grasped the theory fully that naval warfare is a great and far-reaching science, but he put it in practice -- which the French had singularly overlooked. Then was presented the spectacle, not devoid of humor, of Paul Jones sitting at the feet of the French commanders, penetrated with admiration at "the French tactic," as he calls it, while sixty-six French ships of the line hung on to their anchors, closely blockaded by the ignorant English, who were "very defficient in Naval Tactics," as Paul Jones wrote. However, things were made even by the English having the victories, while the French had the tactics.

It is wonderful to note the prescience of Paul Jones in the light of another century. This Revolutionary captain foresaw the use of torpedoes, and experimented boldly with very primitive ones. He understood as fully as a great contemporary writer the "influence of sea power upon history," and wrote, a century and a quarter ago: "In time of Peace, it is necessary to prepare, and to be always prepared for War by Sea." He advocated the establishment of a naval academy, and a supplementary course for officers closely resembling the Naval War College, and advocated the constant study and practice of fleet evolutions. This was in the days when Britannia ruled the waves with a vengeance, but without "tactic." In his admiration for this fascinating part of his profession, Paul Jones certainly underrated the British; but when he came to fight them, he showed them, in his preparations, every mark of respect.

There exists, in his own handwriting, a complete list of every ship of every kind in the British navy, when built, where built, and by whom built, with the names, rates, dimensions, men, guns, and draft of water; also the number of boats of every kind attached to them. It is supposed he had secret correspondence with some person high in the British admiralty to have secured this.

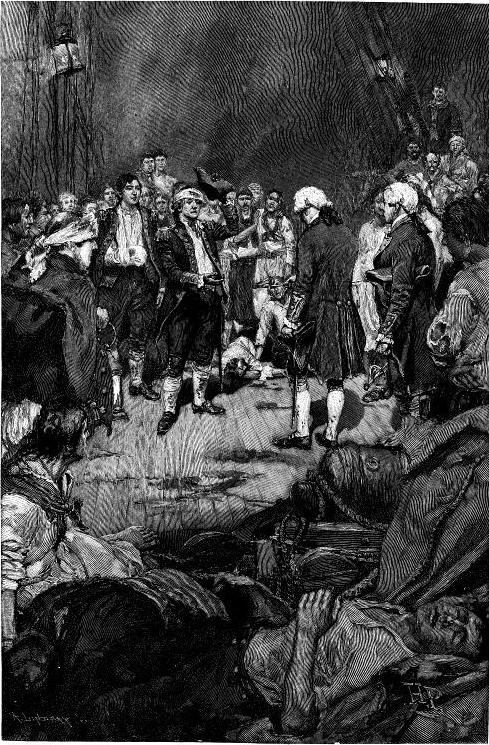

THE SURRENDER OF CAPTAIN PEARSON ON THE DECK OF THE "BON HOMME

RICHARD."

Paul Jones spent some weary months at Brest in a vain effort to get a better ship than the Ranger. He improved her very much, for his practical knowledge of ships was great; but still, as he wrote Franklin, "the Ranger is crank, sails slow and is of triffling force." Nothing better was to be had for him, and many years after he wrote: "Will posterity believe that the Sloop of war Ranger was the best I was ever enabled by my country to bring into active service?"

Like Washington, Paul Jones considered a chaplain as a useful and even a necessary officer; and offered, if one could be procured, to treat him with a distinction greater than any commanding officer has since offered a chaplain. He wrote of this matter: "He [the chap lain] should always have a place at my table, the regulation whereof should be entirely under his direction." The Count d'Orvilliers's chaplain, whom Paul Jones always affectionately addressed as "Father John," was one of his most intimate friends and correspondents. Having determined to traverse the British seas in his little vessel, while d'Orvilliers, with his huge fleet, stayed at home and evolved tactics, Paul Jones was offered a captain's commission in the French navy, the alliance between France and the United States being then consummated. This he promptly declined; and on an April evening he picked up his anchor and steered straight for the Irish Sea. He had lost many of his crew by desertions, and the ship was worse manned and no better officered than when he left America.

One of the strangest things in Paul Jones's career was the success he achieved with "scratch" crews. In his greatest fight, contemporary history says, he had "as bad a crew as ever was shipped," being made up of all nations, among them Maltese, Portuguese, and Malays, who did not always comprehend the word of command. Paul Jones has been severely denounced for having returned to the place of his birth bent on destruction; but, as Cooper justly points out, an officer's oath obliges him to do all in his power to harass the enemy; and it was not only Paul Jones's right, but his duty, to use his knowledge of the Scotch and Irish coasts in the prosecution of the war. If he had any feeling on the subject, it would have been his duty to suppress it. But Paul Jones probably had no feeling whatever, except resentment. He had left his native land as a child, and upon his last visit he had been cruelly ill used, as he thought; and he did his duty on this cruise with no more repugnance than he would have felt at doing it elsewhere -- and did it mercifully.

He spent ten days cruising about the narrow seas, and taking many prizes. He went up the Clyde as far as the rock of Ailsa. He caught sight of the Drake, a twenty-gun sloop of war, in the harbor of Carrickfergus, and crept in upon her at night, intending to grapple and fight it out. The weather was bad, and the Ranger's anchor was let go too soon. Therefore he quietly cut his cable and slipped off. On April 22 he made his celebrated descent upon Whitehaven. He says in his letters to the commissioners that he had two objects in view -- first, the exchange of prisoners; and, second, to "put an end, by one good fire of shipping to all the burnings in America." At midnight he left the Ranger with two boats and thirty-one men. He reached Whitehaven at sunrise. There were nearly a hundred vessels high and dry in the mud of the harbor. The people assembled in crowds; but it never seems to have occurred to anybody that thirty-one men in boats was not a very formidable force. Paul Jones locked up the sentries in the forts, spiked the guns, and fired the shipping. His work accomplished, as he supposed, he prepared to return to the ship, which was many miles away. By that time the country round about was alarmed, and vast crowds ran down to the sea-shore. It is a singular instance of the power of one resolute man, that although Paul Jones stood alone on the pier for nearly a quarter of an hour, no man ventured to approach him. The party reached the ship in safety; but through treachery on the part of a man who deserted them, the fire in the shipping was put out, and in so far the expedition failed. In his report Paul Jones says: "I was pleased that in this business we neither killed nor wounded any person."

Paul Jones now stood for St. Mary's Isle, the seat of the Earl of Selkirk, with the intention of capturing him and holding him as a hostage. The earl was not at home, and Paul Jones returned to the ship. The men, however, began grumbling at not carrying away any plunder; for it must be remembered that in those days looting was considered the legitimate privilege of invaders, although not a prime object, as with Drake, Hawkins, and other buccaneers.

Finding his men mutinous, Paul Jones at last agreed to let them return to the house and ask for plate. They were ordered not to enter the house, to take only what was given them, and to leave at once. This order was strictly obeyed, as Lord Selkirk testified over his own name.

As soon as the party returned to the ship, Paul Jones took possession of the plate, and agreed with the men to pay them the full value of it. In the end he paid about a thousand pounds for it, while it was worth about five hundred pounds, and restored it to Lady Selkirk. His famous letter to her (which, Franklin wrote him, was "a gallant letter which must give her ladyship a high opinion of your generosity and nobleness of mind") is perhaps the worst instance of the vice of fine writing in all literature. He begged a reply from Lady Selkirk's own hand, but got instead a stiffish letter from the earl, declining to accept the plate unless he was allowed to repay Paul Jones the sum paid as an equivalent to the men. Lord Selkirk subsequently got bravely over his scruples, and accepted the plate without conditions. Some years afterward he seemed to wake up to the handsomeness of Paul Jones's conduct, and wrote him a letter acknowledging the discipline of the men, and saying that he had intended to publish a true account of the matter in the newspapers, but that it had already been done. However, he had mentioned it to "several people of fashion" -- which he seemed to think a full equivalent for a thousand pounds in money and an immensity of trouble.

The landing on St. Mary's Isle

thoroughly alarmed the coasts, and the name and character of the

vessel and her commander were well known. The Ranger

being seen beating up the Solway toward the "lang town o'

Kirkcaldy," the frightened people assembled on the shore, and

presently down came their "meenister," the Reverend Mr. Shirra,

lugging a huge arm chair, which he flung down on the shore, and

then plumped himself violently into it. He was short of breath,

and very angry with the Deity for permitting such doings as Paul

Jones's; and, puffing and blowing, he made the following prayer,

which tradition has preserved:

Now, Lord, dinna ye think it is a

shame for ye to send this vile pirate to rob our folk o'

Kirkcaldy? For ye ken they are puir enough already, and hae

naething to spare. They are all fairly guid, and it wad be a

pity to serve them in sic a wa'. The wa' the wind blows, he'll

be here in a jiffy, and wha kens what he may do? He is nane too

guid for onything. Muckle 's the mischief he has done

already. Ony pocket

gear they hae gathered thegither, he will gang wi' the

whole o't, and maybe burn their houses, tak' their cla'es, and

strip them to their sarks! And wae 's me! Wha kens but the

bluidy villain may tak' their lives? The puir women are maist

frightened out o' their wuts, and the bairns skreeking after

them. I canna tho't it! I canna tho't it! I hae been long a

faithfu' servant to ye, Lord; but gin ye dina turn the wind

about, and blow the scoundrel out o' our gate, I'll nae stir a

foot, but just sit here until the tide comes in and drowns me. Sae

tak' your wull o't, Lord!

The prayer appears to have been effective; for at that very moment the wind changed, and blew "the scoundrel out o' our gate."

But Paul Jones had in mind a much greater exploit than frightening women and children, and capturing stray earls. He meant to attack the Drake, and as soon as the wind permitted he was again off Carrickfergus. This was on April 24. The Drake came out to meet the Ranger, which waited gallantly for her adversary, as the tide was unfavorable, and the Drake worked out slowly. Five small vessels came with her to see the fun, and the shores and hilltops were black with people animated with the same desire. Paul Jones's answer to the Drake's hail was in these bold words: "This is the American Continental ship Ranger. We wait for you, and beg you will come on. The sun is but little more than an hour high, and it is time to begin." The fight, as Paul Jones describes it in his journal for the King of France, was "warm, close and obstinate." It lasted an hour and four minutes, when the Drake struck, with her captain and her first lieutenant both mortally wounded, forty-two men killed and wounded, and the ship dismasted and totally disabled. The Ranger lost nine men. It has been the custom among historians unfriendly to Paul Jones to belittle this engagement, and to represent the Drake as an old ship of little force. As a matter of fact, she was a very good twenty-gun sloop, well officered and manned. The Ranger was pierced for twenty-six guns, but Paul Jones considered her capable of carrying only eighteen six-pounders; and he had complained before leaving America that the guns were all three diameters of the bore too short. The Drake carried a complement variously stated by her own men as from 160 to 190 men. Paul Jones thought the truth lay in the middle. The Ranger carried 130 men, mostly bad, with a mutinous first lieutenant. But however small the force on either side might be, nothing can detract from the boldness and brilliance of the attack -- the bolder and more brilliant because such enterprises are usually left to powerful squadrons. Paul Jones sailed back to France by the North Channel. He gave the command of the captured Drake to Simpson as his right; and also, hearing Simpson express a wish for a sword, gave him the dead Captain Burden's. This unwise policy, prompted no doubt by a longing to get back, through Simpson's family connections, the thirteen numbers on the list of captains, turned out as might have been expected. Simpson tried several times to get away with the Drake; and it was only by sheer good luck that Paul Jones caught him, and brought the Drake into L'Orient.

Immense enthusiasm was aroused, and the French government requested that Paul Jones be permitted to remain in Europe, and France was to furnish him with a ship. But the maladministration of French affairs at that time made official promises very uncertain, and his prospect of getting a fine ship soon vanished. No provision was even made for feeding the prisoners. For a whole month Paul Jones paid out of his own pocket for the maintenance of the Drake's people. He returned the officers their swords, and wrote them kindly, offering his testimony before their court martials that they had made "a good and gallant defense, and had not asked for quarter until the Drake was entirely disabled."

It is to be noted that at this very time Paul Jones had advanced to the government more than fifteen hundred pounds besides a large share of the expenses of fitting the Ranger; and he had not received, and for many years did not receive, a penny either in the way of pay or allowance.

But if he got no ship, and no allowance for his prisoners, he was paid many fine compliments, and was received with distinction at Versailles. He loved courts, being a gardener s son; but he conducted himself with dignity when there. The queen, Marie Antoinette, then in the heyday of her charms, treated him with the pretty affability that distinguished her, and won his heart. He wrote of her to Father John: "The Queen is a sweet Girl and deserves to be Happy."

Then began a long series of promises and disappointments about ships and prize-money. The last was of great consequence, as without it it was almost impossible to get a crew. The French court made much of Paul Jones, and the Duc de Chartres, the Prince of Nassau, and others with high-sounding names, were eager to enlist with him, especially Lafayette, who became very intimate with him. But no ship was forthcoming. Franklin had the good will, but no money. Paul Jones wrote letters to everybody in power at Paris, even the king himself, begging for any sort of a ship. At last -- it is said, taking Franklin's advice in "Poor Richard's Almanac": "If you would have your business done, go. If not, send" -- he went to Paris, and the result was that he was put in command of the most extraordinary squadron ever seen, under the most extraordinary circumstances ever known. His flag-ship, which he named the Bon Homme Richard out of compliment to Franklin, was an old Indiaman so much decayed that it was impossible to make any alterations in her. She was mounted with forty guns, mostly old and defective, and had a motley crew of all the nations on the earth, many of them raw peasants, and about thirty Americans whom Paul Jones utilized as petty officers. Her first lieutenant, though, was a young man after Paul Jones's own heart -- Richard Dale, afterward the celebrated Commodore Dale, one of the gallantest, gentlest, and simplest of men. Like the brave and beautiful Maurice, Count Saxe, Dale wrote very ill, although he fought very well. His letters are models of ingenious misspelling, and, like a famous "Boulsprit" which figures in his correspondence, he found penmanship "Something Dificoult in Giting out." Cooper loved and venerated Dale, who in his old age invariably spoke of his friend and captain as "Paul," with a peculiar intonation of love and admiration in his voice. Then there was a fine American frigate -- the Alliance -- of thirty-six guns, commanded by Captain Landais, who had been compelled to leave the French navy on account of an alleged infirmity of temper. There can be no doubt that he was subject to fits of insanity; and his conduct during this memorable cruise was a singular example of crazy cunning. Besides, there were the Pallas, of thirty-two guns; the Cerf, of eighteen; and the Vengéance, of twelve. With this queer collection, and with still queerer arrangements imposed upon him by the French alliance, Paul Jones sailed from Groix on August 14, 1779. The squadron cruised about the coasts of the three kingdoms, sometimes in company, sometimes alone, picking up prizes, and with Paul Jones on the alert for a war-ship not too strong for him to engage. Not so the rest. Cottineau, captain of the Pallas, seems to have been the only captain, except the Bon Homme Richard's, who had any appetite for fighting. As Franklin wrote: "Captain Landais was skilful in keeping out of harm's way." The rest seemed always in the way when they were not wanted, and always out of the way when they were wanted. The cruise was highly unsatisfactory to Paul Jones, and he felt acutely that he was likely to lose, rather than gain, credit by it. In all of his bold propositions he was voted down by his prudent French associates; and if he attempted anything, he was left in the lurch.

On September 13 he was in sight of the Cheviot Hills, and at last inducing the captains of the Pallas and Vengéance to act with him, he sailed up the Firth of Forth to levy a contribution of two hundred thousand pounds at Leith, the port of Edinburgh. Paul Jones's admiration of "the French tactic" does not seem to have extended to the French practice; and after he had spent the whole night persuading them and, as he says, listening to "pointed remarks and sage considerations, the wind became contrary in the morning," and they were blown out to sea.

Although Paul Jones was driven off by the wind, the alarm had been given. Sir Walter Scott told Cooper that, though only a boy of ten years, he remembered well the commotion raised at the time. The Edinburgh people showed a braver spirit than the Whitehaveners, and prepared to defend the town. On the 17th Paul Jones returned, and, after getting nearly within gunshot of the town, a terrific gale arose which drove him off a second time.

Many persons had difficulty in persuading themselves that the mysterious vessel which was seen cruising about was really the American ship. A member of Parliament who lived on the Scotch coast sent out to the Bon Homme Richard -- supposing it to be a British cruiser, for British colors were usually worn -- asking for some powder and shot to defend himself against an attack by Paul Jones. A barrel of powder was sent him, with a civil message regretting that the supposed British cruiser had no suitable shot! Another day a pilot was enticed on board, and persuaded to give the private signals. Meanwhile the time for the cruise to be up was fast approaching, and it may be well imagined that Paul Jones suffered anguish at the idea of returning to France without having exchanged a shot with the enemy. Such, however, was not to be his fate. At noon on September 23, 1779, he sighted the first ship of the Baltic fleet coming around Flamborough Head, and before midnight he had fought the most extraordinary and the most heroic single-ship fight recorded in history.

The fleet of forty ships was convoyed by the Serapis, Captain Pearson, and the sloop of war Countess of Scarborough, Captain Piercy. The Serapis was a splendid frigate, lately off the stocks, and carrying fifty guns -- " the finest ship of her class I ever saw," Paul Jones wrote to Franklin. She carried a crew of four hundred, chiefly picked seamen. Paul Jones had actually on board about three hundred and forty men, and only one sea lieutenant -- Dale. His crew had been decreased by sending prize crews away; while one of his lieutenants, with sixteen men, had been captured, and another during the battle was absent from the ship on a boat expedition. The weight of the Serapis's broadside was 576; of the Bon Homme Richard's, 390. But the Bon Homme Richard's fired only two broadsides when two of the old guns constituting her main-deck battery burst, and the rest cracked and became useless.

The Serapis and the Bon Homme Richard both cleared for action about one o'clock. Each captain knew whom he was fighting. The Serapis manœuvered to get the Bon Homme Richard under the guns of Scarborough Castle, but Paul Jones outmanœuvered him. Meanwhile the Pallas alone obeyed the orders given the rest of the fleet, and eventually captured the Countess of Scarborough very handsomely. The Vengéance never came into action at all, and the Alliance, out of gunshot, reconnoitered cautiously. As the Pallas passed, Captain Landais shouted that if the frigate should prove to be the Serapis, all they had to do was to run away!

There seems to have been a good deal of indiscriminate hailing going on while the ships were approaching each other. The first hail from the Serapis, "What ship is that?" was answered, "Come a little nearer and we'll tell you." The Serapis people called derisively, "What are you laden with?" to which the Americans shouted, "Round, grape, and double-headed shot!"

Paul Jones as a Pirate

From an old print.

With the best dispositions to fight in

the world, the two ships did not come to close quarters until

seven in the evening. The Bon Homme Richard fired the

first broadside, which was promptly returned. Of what followed

Paul Jones himself, in his official report, tells the story

better than anybody else.

The battle being thus begun Was

Continued with unremitting fury. Every method was practised on

both sides to gain an advantage and rake each other; and I must

confess that the Enemie's ship being much more manageable than

the B. h. R. gained thereby Several times an

advantageous Situation in Spite of my best endeavors to prevent

it, as I had to deal with an Enemy of greatly superior force I

was under the necessity of Closing with him to prevent the

advantage which he had over me in point of manœuver. It was my

intention to lay the B. h. R. athwart the Enemie's bow,

but as that operation required great dexterity in the management

of both Sails, and helm and Some of our braces being shot away,

it did not exactly succeed to my Wishes. the Enemie's bowsprit

came over the B. h. R's. poop by the mizenmast and I made

both ships fast together.

At this point occurred an incident which marks Paul Jones's coolness in desperate circumstances; for, as told by him further on, his ship was aleak and afire in a dozen places, her batteries were silenced, a hundred prisoners below were ready to spring up, and some of his petty officers were calling for quarter. When the Serapis's bowsprit became entangled in the Bon Homme Richard's mizzenmast, Paul Jones called to Stacy, his sailing-master, to fetch a hawser, which he did. While making the ships fast, Stacy bungled over it, and burst into an oath. "Don't swear, Mr. Stacy," said Paul Jones. "In another moment we all may be in eternity, but let us do our duty." The spars, anchors, etc., becoming entangled, the two warrior ships were now fast locked in a mortal embrace.

This was the one chance of success -- otherwise the superior sail and battery power of the Serapis would have enabled her to choose her distance and blow the American ship out of the water. Paul Jones's triumphant cry when he saw the ships fast was: "Well done, my brave lads! We have got her now!"

The muzzles of the guns on each ship

were now almost touching, and the gunners had to lean forward

into their enemy's ship to ram home their charges. Cries were

exchanged: "Fair play, you damned Yankee!" "Mind your eye,

Johnny Bull, or I'll -- " etc.

In that Situation which by the action

of the wind on the Enemie's sails forced her stern close to the

B. h. R's. bow, so that the Ships Lay Square along side

of Each other the yards being entangled and the Cannon of Each

Ship touching the opponents side. When this position took place

it Was 8 o'clock previous to which the B. h. R. had received

Sundry Eighteen pound shot below the Water and Leaked Very much,

my battery of 12 pounders on which I had placed my Chief

dependence, being Commanded by Lieutenant Deal and Colonel Weibert, and

manned principally With American Seamen and french Volunteers

was entirely silenced and abandoned. As to the Six old Eighteen

pounders that formed the Battery of the Lower gun deck they did

no Service whatever. two out of three of them burst at the first

fire, and killed almost all the men Who were stationed to manage

them. before this time too, Colonel de Chamillard Who commanded

a party of 20 Soldiers on the poop had abandoned that station

after having lost some of his men.

(These men deserted there quarters) I had now

only two pieces of Cannon, nine pounders, on the quarter Deck

that were not Silenced, and not one of the heavyer Cannon was

fired during the rest of the action. the purser, Mr. Mease, Who

Commanded the guns on the Quarter deck being dangerously wounded

in the head, I Was obliged to fill his place and with great

difficulty rallied a few men and shifted over one of the Lee

quarter deck guns, So that We afterwards played three pieces of

9 pounders upon the Enemy, the Tops alone seconded the fire of

this little battery and held out bravely during the Whole of the

action, Especially the maintop Where Lieutenant Stack commanded.

Paul Jones attached great importance

to having the tops well manned, and had himself carefully taught

his topmen how to fire. So good was their marksmanship that they

soon cleared the Serapis's tops of all except one man,

who, hiding behind the foretopmast, would occasionally peep out

and fire; but he was eventually brought down.

I directed the fire of one of the

three Cannon against the mainmast With double headed Shot While

the other two Were exceedingly well served with grape and

Cannister shot to Silence the Enemie's musquetry and clear her

Decks which was at last effected. the Enemy Were, as I have

since understood, on the instant of Calling for quarter, When

the cowardise or treachery of three of my under officers induced

them to call to the Enemy, the English Commodore asked me if I

demanded quarter, and I having answered him in the most

determined negative, they renewed the battle with redoubled

fury.

What Paul Jones calls a "most determined negative" was the celebrated answer that will ever mark him as one of the bravest of the brave. The two ships lying head and stern, enveloped in smoke as they repeatedly caught fire from each other, and neither one in position to fire an effective shot, a sudden and awful silence ensued. Presently a call came from the Serapis: "Have you struck?" to which Paul Jones answered, "I have not yet begun to fight!"

At this point, also, an attempt was

made to board the Bon Homme Richard. In Captain

Pearson's account of the battle, which is vague and inaccurate,

he says his men discovered a superior number of men armed with

pikes, under cover, ready to receive them; hence they retired.

All accounts agree, on the American ship, that nothing was known

of any attempt to board; but in Paul Jones's journal for the

King of France, he says:

Here the Enemy attempted to board the

Bon Homme Richard, but was deterred from it on finding

Captain Jones with a pike in his hand at the gangway. They

imagined he had as they said, "A Large Corps de Reserve"

which was a fortunate mistake, as no man took up a pike but

himself.

The Serapis was well manned, but her crew was probably out of heart before their officers were.

The American topmen had then climbed

into the Serapis's tops, carrying with them a tub of

water to put out the fire which had begun to smolder in the

maintop. They succeeded in doing this, and then completely

commanded the spar-deck, upon which no man but Captain Pearson

was permitted to show himself.

They Were unable to Stand the deck,

but the fire of their Cannon especially the lower battery which

was Entirely formed of 18 pounders Was incessant. Both Ships

were set on fire in Various places and the scene was dreadful

beyond the reach of Language. to account for the timidity of my

three under officers I mean the gunner, the Carpinter and the

master-at-arms, I must observe that the two first were slightly

Wounded and as the Ship had received various shots under Water,

and one of the pumps being shot away, the Carpinter expressed

his fear that she should sink, and the other two Concluded that

she Was sinking; Which occasioned the gunner to run aft on the

poop Without my knowledge to strike the Colours. fortunately for

me a Cannon ball had done that before by Carrying away the

Ensign staff. he was therefore reduced to the necessity of

Sinking, as he Supposed, or of Calling for quarter, and he

preferred the Latter.

Paul Jones does not mention that he

knocked the gunner down with his pistol-butt. The only

punishment given the man afterward was to stand him at the mast.

All this time the B. h. R. had sustained the action alone, and the Enemy tho' much Superior in force Would have been Very glad to have got clear, as appears by their own acknowledgments, and by their having let go an anchor the instant that I Let them on board, by Which means they would have escaped, had I not made them Well fast to the B. h. R.

At Last, at half past nine o'clock the Alliance appeared and I now thought the battle at an end, but to my utter astonishment he discharged a broadside full into the Stern of the B. h. R. We called to him for god's sake to forbear firing into the B. h. R. Yet he passed along the off side of the Ship and continued firing. there Was no possibility of his mistaking the Enemie's ship for the B. h. R. there being the most essential difference in their appearance and Construction, besides it Was then full moon Light and the Sides of the B. h. R. Were all black, While the Sides of the prises were yellow. Yet for the greater Security I shewn the Signal of our Reconnaissance by putting out three Lanthorns, one at the head (bow) another at the Stern (Quarter) and the third in the middle in a horizontal line. Every tongue cried that he was firing at the Wrong ship, but nothing availed, he passed round firing into the B. h. R's. head stern and broadside, and by one of his Vollies killed (Eleven) several of my best men and mortally Wounded a good officer on the forecastle only. my Situation was really deplorable, the B. h. R. received various shots under Water from the Alliance, the Leack gained on the pumps, and the fire increased much on board both Ships. Some officers persuaded me to Strike, of Whose Courage and good Sense I Entertain a heigh opinion.

To the representations of these

officers that the Bon Homme Richard could not possibly

float much longer, Paul Jones replied pleasantly, "Never mind

about that. We shall have a better ship to go home in!"

My treacherous Master at Arms let

Loose all my prisoners Without my knowledge, and my prospect

became gloomy indeed.

In his journal he says:

This must have ruined Captain Jones,

had not the prisoners been terrified out of their senses.

Captain Jones availed himself of their fears, and placed them to

work at the pumps.

The audacity of this conception carries Paul Jones well into the camp of the greatest humorists of the world. If the prisoners had kept their wits about them, they could easily have stepped through the ports of the crazy, leaking, and burning Bon Homme Richard into the comparatively uninjured Serapis, instead of which all their powers were engaged in saving their captor's ship, and securing their own imprisonment for several months thereafter. At this point one of the sailors of the Bon Homme Richard, taking a bucket of hand-grenades, laid out on the main-yard, which was directly over the main hatch of the Serapis, and coolly fastening his bucket to the sheet-block, began to throw the grenades down the hatchways. Almost the first one rolled down the hatch, and falling among a row of cartridges left exposed by the carelessness of the Serapis's powder-boys, a terrific explosion followed. This seems to have been the turning-point. Paul Jones continues:

I would not however give up the point. The Enemie's main mast began to Shake their firing decreased, We rather increased and the British Colours were struck at half an hour past ten o'clock.

The flag had been nailed to the mast;

and Captain Pearson, who had ordered every man off the

quarter-deck, while himself bravely remaining, lowered the flag

with his own hands, and not without difficulty. He had lost, as

nearly as can be computed, about one hundred men killed, and

nearly the same number wounded. The Bon Homme Richard

had forty-two killed and forty wounded.

This prize proved to be the British

Ship of War the Serapis, a new Ship

of 44 Guns built on their most approved

Construction With two complete batteries, one of them of 18

pounders and Commanded by the brave Commodore Richard Pearson.

In the journal for the king, Paul

Jones says:

There was no Occasion for a Bridge

between the two ships. Captain Pearson stept on board the Bon

Homme Richard, and delivered up his Sword to Captain

Jones, who returned it to him, because he had bravely used it.

The story that Captain Pearson said, in giving up his sword, that it added to his mortification to give up his sword to a man who fought with a rope around his neck, is an idle fabrication, and a slur on Captain Pearson.

Paul Jones continues:

I had yet two Enemies to encounter far more formidable than the britons, I mean fire and Water. the Serapis Was attacked only by the first, but B. h. R. Was assailed by both, there was five feet Water in the hould, and tho' it Was moderate from the Explosion of so much gun powder, yet the three pumps that remained could with difficulty only keep the Water from gaining. the fire broke out in Various parts of the Ship in spite of all the Water that Could be thrown (immediately) to quench it, and at lenth broke out as low as the powder magazine and within a few (feet) inches of the powder. in that dilema I took out the powder upon deck ready to be thrown overboard at the last extremity, and it Was ten O'clock A. M. the next day the 24 before the fire Was entirely extinguished. With respect to the Situation of the B. h. R. the rudder Was cut Entirely off the stern frame and transoms Were almost Entire Cut away (and) the timbers by the lower Deck especially from the mainmast to the stern, being greatly decayed With age, were mangled beyond my power of description, and a person must have been an Eye Witness to form a Just idea of the tremendous scene of carnage, Wreck and Ruin (which) that Every Where appeared. humanity cannot but Recoil from the prospect of such finished horror and Lament that War should (be capable of producing) produce such fatal consequences.

After the Carpinters as well as

Captain De Cottineau and other men of Sense had well examined

and Surveyed the Ship (which was not finished before five in the

Evening) I found every person to be convinced that it was

Impossible to keep the B. h. R. afloat So as to reach a

port if the Wind Should increase it being then only a very

moderate breeze. I had but little time to remove my Wounded,

which now became unavoidable and which Was effected in the

Course of the night and next morning. I was determined to keep

the B. h. R. afloat and, if possible, to bring her into

port for that purpose the first Lieutenant of the Pallas

continued on board with a party of men to attend the pumps with

boats in Waiting ready to take them on board in Case the water

should gain on them too fast. the Wind augmented in the Night

and the next day on the 25, So that it was Impossible to prevent

the good old ship from Sinking. they did not abandon her till

after nine o'clock. the Water was then up to the Lower deck, and

a little after ten I saw With inexpressible grief the last

glimpse of the B. h. R.

By Paul Jones's orders an American ensign was left flying, and the ship he had immortalized went down, head foremost, still wearing the colors he had so well defended.

Naval experts have agreed that there were no new principles evolved, and no extraordinary tactics shown, in this remarkable fight. But it stands alone among sea fights in that the ship which finally forced a surrender might have been considered a beaten ship from the beginning. There was not a moment, after the second broadside, that the Bon Homme Richard was not technically whipped. But her captain was unconquerable, and by an unexampled tenacity and courage forced the surrender of a good ship to the shattered, disarmed, and burning shell of the Bon Homme Richard. English historians have generally ascribed the result of the fight to the presence of the Alliance, and have naturally accepted Captain Pearson's official report of the battle, in which he says he struck upon the approach of the fresh frigate. But Captain Pearson's ignorance of the real conditions of the fight is the one thing which excuses his surrender. It would be an undeserved reflection upon a brave man to suppose that he knew the desperate state of the Bon Homme Richard. It would not have affected Captain Pearson's prestige, promotion, or purse, had he struck to the fresh frigate after he had made the Bon Homme Richard strike to him. But Pearson was hard pushed for reasons to give for his surrender, being loath to acknowledge how little he knew of his enemy's desperate straits. Paul Jones expressly says Pearson was astonished at the havoc on the American ship. As for the Alliance, she was perfectly inactive and out of gunshot, except when she was firing into her consort; and three of Landais's own officers declared, on oath, that he said, during the engagement, "he would have thought it no harm if the Bon Homme Richard had struck, for it would have given him an opportunity to retake her and take the Serapis" -- an idea quite worthy of Landais's touched brain. Pearson was a man of great courage, but of ordinary abilities; and he had to contend against a man of extraordinary courage and extraordinary abilities. Like Paul Jones, he was of humble origin; but, unlike Paul Jones, he showed it in a petulance unworthy of a gentleman. He did not, however, lack for defenders among his own people. The British, and especially the London, public were determined to regard the giving up of the Serapis as a victory for Captain Pearson instead of Captain Jones; and the London merchants made Pearson a present of plate to the value of one hundred pounds. Captain Piercy, who had made a gallant fight before surrendering the Countess of Scarborough to Captain Cottineau of the Pallas, was also given plate to the value of fifty pounds. Moreover, Captain Pearson was made a knight -- presumably because he had done no worse. On hearing of this, Paul Jones remarked: "He has deserved it; and if I should have the good fortune to fall in with him again, I will make him a lord."

During the fight Paul Jones was severely wounded in the head, which afterward greatly affected his eyes, and at various times he received other injuries; but there is no mention in any line of his official reports of his wounds, although he frequently called attention to the wounds of others.

From an Old Print. Captain Paul Jones.

The squadron -- or what was left of it -- now sailed for the Texel, where it arrived on October 3. The Dutch people warmly sympathized with the American cause; but the court and the court party were completely dominated by the British ambassador, whom Paul Jones angrily calls "that little Thing, Sir Joseph Yorke." When Paul Jones appeared on the Exchange, he was so nearly mobbed by his admirers that he had to take refuge in an upstairs room. O'Connell, one of his officers, was often mistaken for Paul Jones, and his sufferings while trying to explain in English to the Dutch that he was not Paul Jones are very piteously described. The men were popular among the Dutch sailors and citizens, and there exists a touching appeal from the petty officers for "certain Artickles without which they cannot appear with any degree of Credit to their Comodore or themselves." Last but not least of these requisitions is this: " Mr. Potter" (the carpenter) "having lost his Hair is in Want of a Wig." It is hoped that this patriot got his wig.

Franklin wrote a very beautiful letter

to Paul Jones, in which he said:

For some Days after the Arrival of

your Express, nothing was talked of at Paris and Versailles, but

your cool Conduct and persevering Bravery during that terrible

conflict. You may believe the Impression on my mind was not less

strong than that of others, but I do not chuse to say in a

Letter to yourself, all I think on such an occasion. . . . I am

uneasy about your Prisoners, and wish they were safe in France.

You will then have Compleated the glorious work of

giving Liberty to all the Americans who have so long

Languished in British Prisons: for there are not so many there

as you have now taken.

In this letter Franklin directs Paul Jones to put Captain Landais under arrest, and announces a determination to punish Landais severely, which he finally accomplished under great difficulties. Sir Joseph Yorke addressed a letter to their High Mightinesses denouncing Paul Jones as a "pirate and rebel," and inviting them to hand over the Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough to himself. This their High Mightinesses prudently declined to do, although they were most unfriendly to the American cause. Captain Pearson behaved in a manner totally unworthy of so brave a man and of the generous treatment he had received from his captor. When Paul Jones offered to return him all his plate, linen, etc., from the Serapis, he refused to accept it, but intimated that he would take it from Captain Cottineau. Paul Jones magnanimously overlooked this vulgar subterfuge, and returned it through Cottineau. After this, Pearson wrote him a querulous letter complaining that Paul Jones had not called to see him! To this Paul Jones returned a dignified answer, refuting the charge of a want of civility.

The court party pretty soon informed Paul Jones that unless he got away he would be driven away. Menaced by thirteen double-decked Dutch frigates inside the harbor, while twelve British ships of the line and frigates cruised outside, often in full sight, waiting for him, his situation was perilous in the extreme. The court party had power enough to give him the choice of surrendering the Serapis to his French colleagues, or of hoisting the French flag and accepting a commission in the French navy in order to hold her. This was a cruel alternative; but between giving up the ship and hauling down the American colors, he chose the better part, and transferred his flag to the inferior Alliance, and for the second time refused a French commission. The French ambassador, the Duc de Vauguyon, committed the astounding faux pas of suggesting to Paul Jones that he take command of a French privateer, and thus escape from his dangerous situation in the Texel. Paul Jones's reply to this was an instant and haughty demand for an apology, which was promptly forthcoming. No man hated privateering and its "infernal practices," as he calls them, more cordially than Paul Jones. He wrote of privateers as "licensed robbers," and was naturally indignant at the affront offered him. Some years afterward, in a French port, he had an amusing controversy on the subject with Captain Truxtun, afterward the celebrated Commodore. Truxtun was then in the humble capacity of captain of a private ship bent on plunder. He had the assurance to raise a pennant in the presence of Paul Jones, without asking his permission, and in defiance of the act of Congress forbidding a privateer to hoist a pennant under such circumstances without the permission of a naval ship's commander. They had a tart correspondence, and Commodore Truxtun was evidently mightier with the sword than with the pen, as Paul Jones writes him that there are in his letter "several words I do not understand and cannot find in the Dictionary." Paul Jones sent him "a polite message" to haul down the pennant. This being disregarded, another polite message and "Lieutenant Richard Deal" with two armed boats were sent, and the pennant came down.

To return to the Texel. In spite of the strongest protests from the British ambassador, and constant threats from the Dutch government, Paul Jones remained there nearly three months. He, moreover, demanded and obtained the free disposition of his prisoners, liberty to have the drawbridge hauled up at his pleasure, and refused flatly to go on board the Dutch flag-ship, although repeatedly commanded to do so. The Dutch were anxious to be rid of so troublesome a guest, whose presence embroiled them with Great Britain -- eventually to the point of war; and with joy saw him set sail on December 27, in the midst of a howling gale, and, as he wrote at the time, "with my best American Ensign flying." He returned to France by the route least expected by his enemies. He went by way of the North Sea to the Strait of Dover, passing in full view of the British fleet in the Downs. He was two days in the English Channel, going close by the Isle of Wight and by the fleet at Spithead. He made Corunna on January 16, and the port of L'Orient some days after. This retreat may be reckoned as both brilliant and fortunate. His conduct in keeping his flag flying in the face of twenty-five hostile ships, any one of which was a match for the Alliance, raised the American name to a point of great dignity; and the service he rendered in detaching Holland from Great Britain was of incalculable benefit to his country.

His wound, and the hardships he had undergone, kept him closely confined at L'Orient for some time; but in May he went to Paris, and found himself the hero of the hour. The American commissioners paid him every honor. The court and the public vied with each other in complimenting him. Baron de Grimm, in his letters, speaks of Paul Jones's popularity at court. He sat in the queen's box at the opera, and on his first appearance at the theater the audience rose and cheered him. At the end of the performance a laurel wreath was suspended from the ceiling directly over his head. He rose quietly, and moved away -- an instance of modesty which is to this day held up as a model to French school-boys.

The king gave him a superb gold-hilted sword inscribed, "Vindicator maris. Ludovicus XVI., Remunerator strenuo vindici." Paul Jones mentions that it was much handsomer than the one presented to Lafayette. It cost about $2400. Louis also directed M. de Luzerne, the French ambassador to the United States, to obtain the consent of Congress for Paul Jones to accept the Grand Cross of the Order of Military Merit, never before awarded a foreigner, which was done.

At this time tradition begins a long list of Paul Jones's love-affairs and gallantries. There is no doubt that he was a lion among the ladies, and had a roaring flirtation with the Countess Lavendahl de Bourbon. She was much younger than her husband, and chroniclers note that she was more renowned for wit than for discretion. She painted Paul Jones's portrait, and wrote verses under it. He so far lost his head over this lady that he wrote her most violent love-letters, inclosing locks of his hair; and asked her to take care of his sword on his approaching voyage to America, and to correspond with him in cipher. The countess seemed to think at this point that the affair had gone far enough, and that it was time to throw cold water on her too ardent admirer. Paul Jones got out of his awkward predicament with as much skill as he had escaped from the Texel. He assured the lady he was not in the least in love with her -- friendship, and friendship only, was all he meant, and she had evidently misunderstood him -- which effectually landed the lady in the awkward predicament. He seems, however, never to have lost her respect; for the correspondence was resumed in after years. Then there was a Madame Thellison, a natural daughter of Louis XV., with whom Paul Jones appears to have had a love-affair of some sort. He had influence enough to have her introduced to the king, who promised to befriend her. Afterward Paul Jones wrote Mr. Jefferson, then minister to France, recommending Madame Thellison to his friendly offices. He mentioned that he had borrowed for her four thousand livres with which to pay a debt, and had never found out whether she had used the money for the purpose specified or not. He was in the midst of a corrupt court; and although he may not have escaped uncontaminated, it is an admirable fact that among the 1300 letters written by and to him, now preserved, there is not one single coarse expression, and no woman's name is mentioned except in terms of the highest respect. This speaks well for the chivalry of those eighteenth-century gentlemen.

The same troubles about prize-money, disappointments, and shuffling tactics that followed the capture of the Drake, again followed the capture of the Serapis; and it was not until the autumn of 1780 that Paul Jones sailed for America, in the Ariel; a lightly armed vessel, with stores for Washington's army.

On his first departure he encountered a storm which has been described as the worst one of the century. His ship was nearly wrecked off the Penmarque Rocks. Dale, who was still his first lieutenant, said many years afterward: "Never saw I such coolness and readiness in such frightful circumstances as Paul Jones showed in the nights and days when we lay off the Penmarques expecting every moment to be our last; and the danger was greater even than we were in when the Bon Homme Richard fought the Serapis."

He was forced to return for repairs, and did not reach the United States until February, 1781. He was received with every mark of honor. Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and Morris were among those who wrote him letters of congratulation. The Congress at three different times passed resolutions in his honor -- the last, on April 14, a formal vote of thanks, recording: "That the thanks of the United States in Congress assembled be given to Captain Paul Jones, for the zeal, prudence and intrepidity with which he has supported the honour of the American flag; for his bold and successful enterprises to redeem from captivity the citizens of the States who had fallen under the power of the enemy; and, in general, for the good conduct and eminent services by which he has added luster to his character and to the American arms."

Soon after this he was unanimously elected the ranking officer of the American navy, and appointed to superintend the building and to have command of the Government's only seventy-four, the America, then on the stocks at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Nearly two years were spent in this employment, at the end of which time the ship was presented to France, in lieu of one that had been lost in Boston harbor.

Having been disappointed in this, as in all his other hopes of commanding a fine ship, Paul Jones got permission to embark with the Marquis de Vaudreuil, who, with a large fleet, was taking back to France the French contingent under the command of the Baron de Viomesnil and the Marquis de Laval. He was received on board the flag-ship Triompizanfe, which was much crowded, sixty officers dining in the wardroom every day. Paul Jones notes that he was given the state-room on the starboard side, while the baron and. the marquis had to take the port side. His object in this cruise was to "acquire marine knowledge," as he says; for no man ever yearned for knowledge more than Paul Jones. The declaration of peace found the fleet in the West Indies, and Paul Jones returned to the United States. Viomesnil wrote to M. de Luzerne, French ambassador to this country: "M. Paul Jones has for five months deported himself among us with such wisdom and modesty as to add infinitely to the reputation gained by his courage and exploits."

He was soon after appointed government agent to settle the matter of the prize-money of the Bon Homme Richard, and gave a bond to the government of $200,000, which was fully equal to a million in this day. He landed at Plymouth, England, and went to London, where he remained for a day or two the guest of John Adams. From London he went to Paris. He proved to be a passionate but acute advocate; and although the plainness of his language must have made the French diplomats' hair stand on end, he finally succeeded in getting the money -- a feat but slightly inferior to his fight with and capture of the Serapis. He made no charge for his services, but only for his expenses, which were, however, large. He went to court, and "mixed with the great." Jefferson, his tried friend, was then minister to France. Paul Jones at this time became acquainted with John Ledyard, who had been with Captain Cook in his last voyage. Ledyard gave him an account of the vast wealth in fur-bearing animals in the Pacific, which recent years have so amply confirmed. Paul Jones's perspicuous mind saw the reasonableness of this, as did Jefferson and Robert Morris; but although an elaborate plan was formed for an expedition, it fell through. It was during this visit that he wrote his account of his adventures in the service of the United States, which was handed about from one person to another at the French court. It was read, among others, by M. de Malesherbes and Count d'Estaing, both of whom wrote complimenting him highly on the relation, which was undoubtedly full of interest, and written in a captivating style, as he was not then writing to a countess, but merely telling, with a sailor's directness, what happened to him with a ship.

At this time he was well received by Englishmen of high character at Paris. He frequently visited the British Embassy, being on friendly terms with the ambassador, the Duke of Dorset. Lord Wemyss was another friend of his, and the brave Admiral Digby sought his acquaintance. He returned to the United States in the spring of 1787, when Congress approved of his accounts, allowed all he asked, and presented him with a gold medal with a gratifying inscription. There were still some unsettled affairs concerning certain prize ships that had been sent to Denmark and seized and sold by the Danish government. Paul Jones was empowered as agent in this matter, and the Congress gave him a special letter of recommendation to Louis XVI.: one of the greatest honors ever bestowed by the United States on a citizen. In December he landed at Dover, and went to London, where he conferred with Mr. Adams on the Copenhagen affair. After a few days in England, he went to Paris. The first person he informed of his arrival was Mr. Jefferson, whom he asked to keep it secret, but to call on him at his hotel in the Rue des Vieux Augustines. Mr. Jefferson called promptly, and unfolded to him a brilliant scheme for Paul Jones's further advancement. M. de Simolin, the Russian ambassador, had asked Mr. Jefferson to sound Paul Jones on the subject of accepting a high command in the navy of the Empress Catherine, who was then at war with the Turks. This prospect was much more pleasing to Paul Jones than being with a French squadron of evolution, which he must have been convinced by that time meant more evolution than fighting. He agreed that, after having settled his business at Copenhagen, he would go to St. Petersburg and consider the offer. He went to Copenhagen, arriving in March; and was presented to the court with all the prestige the French ambassador could command. As usual, Paul Jones was greatly impressed with the civilities of the great. The queen dowager was full of "dignity and deportment," the princess royal was "a charming person," the prince royal "extremely affable"; and he was invited to sup with the royal family; which gave him more pleasure than one would have imagined. But he soon after wrote to Count Bernstorff, Danish minister of foreign affairs, that although "particularly flattered by the polite attentions" bestowed upon him, "yet I have observed with great concern, you never lead the conversation to the subject of my mission here." Count Bernstorff's letter in reply is a gem of diplomatic platitudes, and for once Paul Jones found his adversary too slippery for him. The ingenious Bernstorff found some flaw in the powers conferred on Paul Jones, and as Mr. Jefferson was then negotiating a treaty with Denmark, the affair went over. Paul Jones, however, accepted, with the knowledge and approval of Mr. Jefferson, the offer of a sum of money from the Danish government -- presumably his share of the prize-money. This sum, however, was never paid, and the particulars of the subject are not known. On this northern journey his health first began to fail. At last, in April, 1788, he left Copenhagen to accept a commission in the Russian navy, for which he had not up to that time received specific permission from the United States. He wrote to Mr. Jefferson: "I must rely on your friendship to justify to the United States the important step I now take, conformable to your advice. ... I can never renounce the glorious title of a citizen of the United States."

It would seem that the prospect of gaining new honors was so fascinating to Paul Jones that he was willing at Copenhagen to undertake real service under very discouraging circumstances. Instead of being made a rear-admiral, as he expected, he was offered the commission of captain-commandant; and when he objected, he was supposed to be appeased with the promise of a major-general's commission! To the surprise of the Russians, he declined to become a major-general. He showed his old spirit of daring in his journey to Russia. He determined to go by sea, owing to the blockade of the land route with snow. He engaged a large and a small boat at Gresholm, and without telling the men where he was going, put off in ugly weather. When opposite Stockholm he forced the sailors at the point of a pistol to enter the Baltic Sea, and thence they were driven by the wind into the Gulf of Finland. The small boat was lost, but all the men were saved. After four days they were landed at Reval in Livonia. The voyage had never been made before at that season, and was counted until then an impossibility. Paul Jones mentions that he had a small compass, and by fixing the lamp of his traveling-carriage to it he was enabled to see.

He was received with great honors at St. Petersburg, and, as usual, found everything lovely at first sight. The empress "entirely captivated" him; Potemkin was but little less captivating. He was made a rear-admiral at last, which caused thirty English officers to wait upon Admiral Grieg and declare their determination not to serve with Paul Jones. Their protest was disregarded, and Paul Jones was despatched to the Liman to take charge, as he supposed, of naval operations against the Turks. He found, however, that his command had to be divided with an old acquaintance of his, the Prince of Nassau, a gentleman adventurer, of whose personal courage Paul Jones expresses a very poor opinion, adding that the prince had sailed around the world, yet did not understand the points of the compass. In Potemkin and Nassau he had a precious pair to deal with. They thought him crazy because he expressed respect for, and treated courteously, the brave old Turkish commander. In the mass of correspondence, diplomatic and otherwise, the facts are not really difficult to discover. Paul Jones was still Paul Jones, but he had a spoiled court favorite and a conscienceless adventurer to satisfy, and also to withstand the enmities and prejudices of the English officers. Nevertheless, all that was done of value in the campaign was done by him.