A B C D E F G H J K L M N

O P R S T U/V W/Z

A

[ Top of Page ]

John Adams (7): John Adams (1735-1826) was an important political figure in the American Revolution, serving in the Continental Congresses and in diplomatic positions. He helped draft the "Declaration of Independence." In 1777-8, he served with Benjamin Franklin as a commissioner to France. He eventually became the second President of the United States (1797-1801).

Sam Adams (2): Samuel Adams (1722-1803), sometimes, Mr. Adams, of Massachusetts, was a major figure in many aspects of the American Revolution.

Agamenticus (and the Three Hills) (7): In Piscataqua Pioneers (2000) Sylvia Getchell says Agamenticus was the Indian name for the York River (11). In histories of Maine, the whole area that now comprises York County in Maine is sometimes called Agamenticus. The settlement area of Agamenticus was renamed Gorgeana when chartered in 1642 and then renamed York in 1652, when it was reorganized as a town. (See Maine: A Guide 'Down East,' 1937.) Mt. Agamenticus is about mid-way between South Berwick and Ogunquit. A little northeast of Mt. Agamenticus is Second Hill, and somewhat further in the same direction is Third Hill.

Ajax (2): Negro servant of Judge Benjamin Chadbourne. See Cæsar below.

Alençon (21): On a route from Brest to Paris, Alençon is about 3/4 of the way. In the 18th-century the town was known for its lace and textiles.

Apollo (8): Haggens family slave. See Cæsar below.

Arbigland (6,22): The fishing hamlet where John Paul Jones was born in the western lowlands of Scotland on the north shore of Solway Firth near the present-day village of Kirkbean. The village is across the firth from Whitehaven.

Le petit Arouet: See Voltaire below.

B

[ Top of Page ]

Bath (34): East of Bristol, England, on the Lower Avon River. Graham Frater writes: "Modern roadmaps show that the city of Bath is some 13 miles to the south east from Bristol city centre. Bath was developed by the Romans for its hot springs; much of the eighteenth century city that Jane Austen described still survives (see: www.janeausten.co.uk), as do many Roman remains, including their baths. Jewett refers to no specific locations within Bath; this may argue that she did not visit the city, but her appreciative descriptions of the countryside on the journey to Bath do perhaps suggest first-hand observation; they certainly invoke the links between England and America that Jewett had emphasised in her conclusion to The Story of the Normans, and in her childrens novel with an English setting Betty Leicester's Christmas."

Badger Island (29): See Langdon's Island

the Banks (12): This could be Georges Banks, a fishing ground off the coast of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, or the Grand Banks, another fishing ground south of Newfoundland, Canada.

Bantry (3,17): On the southern coast of Ireland, on Bantry Bay.

Praise-God Barebones (8): The "Barebones" parliament, called by Oliver Cromwell in 1653, was so named derisively, according to the Encarta Encyclopedia, because one of its Puritan members was named "Praisegod Barbon or Barebone, a leather merchant."

Barrington (36): William Wildman Shute, 2nd Viscount Barrington (1717-1793) began government service in the Irish House of Lords in 1745. He became a member of the British Parliament in 1754 and then served in the Exchequer and other offices. During the American Revolution, he was Secretary of War (1765-1778). For details see: Shute Barrington, Political Life of William Wildman, Viscount Barrington (1814). Lossing characterizes Lord Barrington as strongly opposed to the American rebellion: "In the upper House, Lord Barrington called the Americans "traitors, and worse than traitors, against the crown -- traitors against the legislation of this country. The use of troops," he said, "was to bring rioters to justice" (vol. 2; ch. 6).

Barvick (2 and several other chapters): See Berwick.

Basilica of St. Denis: See Paris.

Beare (3 and others): The area of southern Ireland over which the O'Sullivan family (Master Sullivan's ancestors) ruled prior to the 17th century.

Abbé de Beaumont (17): Master Sullivan says he knew the Abbé, a nephew of Fénelon, and with him visited Fénelon at Cambrai. In Butler's Life of Fenelon, de Beaumont is mentioned as a friend and subordinate teacher under Fénelon to the royal dukes, and as his nephew (p. 112). In The Age of Louis XIV, Voltaire mentions him as "the king's tutor," who helped to insure that plays were performed at court despite Jansenist objections (Ch. 25).

Bedfords (32): Mme. Wallingford "hates" these people for their treatment of American Loyalists. Probably she refers to John Russell, 4th duke of Bedford (1710-71), a leader of the "Bedford Group" of Whigs who were conciliatory toward American colonials. Her use of the plural in Chapter 32 suggests she is referring to the group as well as to John Russell, who had been dead for about 7 years when she made her statement.

Beech Ridge (9): There is a Beech Ridge in DeLorme's The Maine Atlas (2001), about 2 miles west of York Village, and another, more likely to be the location Jewett refers to, northeast of Berwick, nearly half way to Sanford. This location along with Tow-wow/Lebanon would indicate the length of Colonel Hamilton's journey - more than 20 miles round trip - the day after the Ranger sails. It would be convenient for Hamilton to stop as expected for dinner with Master Sullivan at Pine Hill, though he does not on this day.

Belle Isle (18): In France; see Breton coast.

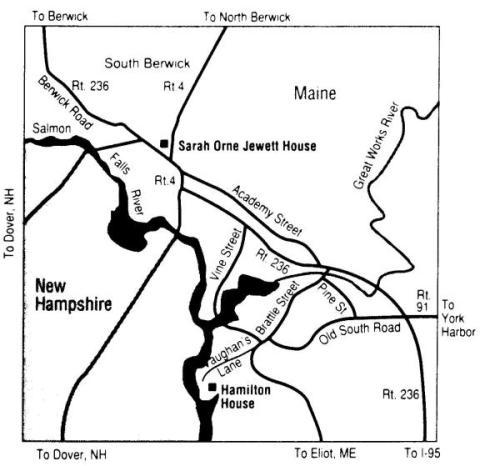

Berwick (1 and many other chapters): On the Salmon Falls

River in southern Maine, sometimes referred to as "Old Barvick."

Since 1814 the original Berwick has been divided into the three

neighboring towns: Berwick, North Berwick and South Berwick, the

home of the Hamiltons. South Berwick, Jewett's birthplace and

home, was the original settlement, and it is divided into regions

that have been centers of commerce during the town's history.

These are listed after the map.

Map of South Berwick, from a Hamilton

House.brochure.

Upper Landing (28 and others): At

the head of the tidewater, sometimes called Quamphegan, the last

place at which boats could land going up river, just below Salmon

Falls. Today this location remains a landing for small boats, and

is the site of the Counting House Museum of the Old Berwick

Historical Society, with exhibits open on weekends and by

appointment, and with reference, document, and artifact

collections for research in local and regional history.

On the map, it is north of the river and to the

right of the road from Dover, N.H.

Upper Landing in 2003

View of the Upper Landing from the Highway 4 bridge

by Terry Heller, 2003

Lower Landing (8,29): About one mile down river from the Upper Landing, in deeper water near Hamilton Brook, where Hamilton House is located. Also known in early settlement times as Pipe Stave Landing, because barrel staves, called pipe staves, were an important local export in the Caribbean trade.

Great Works (2): From the 17th through the 19th century, Great Works referred to a mill area -- first lumber, later wool processing -- on the Great Works River in South Berwick. This area along with Old Fields, was the earliest settled part of the town. During the 1770s, the village center was moving westward, to the location near Jewett's home, the house where Tilly Haggens is said to live in the novel. (See Tilly Haggens's House below).

Other South Berwick landmarks and locations in the novel:

Butler's hill (8): Tilly Haggens could see this hill on his left while sitting on the front porch of the Jewett house in November of 1777 at the beginning of Ch. 8. This is now known as Powderhouse Hill; it is the site of the Berwick Academy. Source: York County Atlas of 1872. The Butler family, in their genealogy at the Old Berwick Historical Society, believes the hill was named for Thomas Butler (b. 1674), who settled in Maine around 1695, and whose homestead was at the foot of this hill.

Tilly Haggens's House (8):

See Chapter 8 for Photographs.

This house is now known as the Jewett House, where Sarah Orne

Jewett was born and where she lived after the death of her Uncle

William Jewett in 1887. Wendy Pirsig points out that the "broad

space" in front of the Haggens house was a watering place for

animals for many years -- a spring/cistern was below the street.

Jewett describes the front porch as having Corinthian columns, but

this seems to be an error. It is possible that Jewett did not

distinguish the styles of classical columns; in "The Old Town of

Berwick" she says the First Parish Church once had Corinthian

columns, but this church actually has relief decorations

representing Doric columns.

Whether the historical Tilly Haggens

actually built or lived in this house is a contested issue; see

Tilly Haggens in Extended Notes.

Old Fields (28,31): Everett S. Stackpole in "South Berwick: The First Permanent Settlement in Maine," locates Old Fields at the southern end of the current village of South Berwick. He says this was originally the location of the Spencer Garrison, built before 1675 a site associated with the northernmost limit of Old Fields Road, and with the Ichabod Goodwin house, 1 Old Fields Road. It includes the site of the Old Fields Cemetery, where several of the local historical characters of this novel are buried. Hamilton House stands on the river in the Old Fields area. See "The Old Town of Berwick" for a photograph. On the map, this area is northeast of Hamilton House.

The Old Vineyard (28,32): Everett S. Stackpole in "South Berwick: The First Permanent Settlement in Maine," locates the old vineyard just north of the mouth of the Great Works River in South Berwick. What remains of this area now faces Leighs Mill Pond on Vine Street in South Berwick.

Plaisted¹s Hill (8): Probably this is the site of a Plaisted farm on the Berwick Road about half a mile from Haggens house. In the 17th century, a Plaisted family owned one of the earliest farms along the Salmon Falls River, scene of an Indian raid in 1675. See Jewett's "The Old Town of Berwick" and also Hertel on the list of People.

Pound Hill/ Pound Hill Farms (28): No map has been found identifying this area. Jewett says that when the bringers of news from Portsmouth leave the Lower Landing, "The messengers were impatient to go their ways among the Old Fields farms, and went hurrying down toward the brook and around the head of the cove, and up the hill again through the oak pasture toward the houses at Pound Hill." This would seem to place Pound Hill east of Hamilton House. Norma Keim of the Old Berwick Historical Society has located the actual hill on what is now Fife's Lane, which once was part of the main road from Old Fields to York. This location is just east of Old Fields. See The Maine Spencers, A History and Genealogy by W. D. Spencer (Concord: Rumford Press, 1898) p. 108. It is quite likely that the name derives from the location of the village livestock pound. In the colonial period, many New England villages had pounds where strayed livestock would be kept at village expense until the owners claimed them and payed their fine or pound fee. (See John R. Stilgoe, Common Landscape of America 1580-1845. New Haven: Yale UP, 1982, p. 49).

Duke of Berwick: The Duke of Berwick is not referred to in

The Tory Lover, but Jewett meant to include him. See Duke

de Sully below.

According to the web site of the Wild

Geese Heritage Museum and Library in Galway, Ireland, by Sean

Ryan, the Marshal Duke of Berwick (1670-1734) was James FitzJames,

Marshal of France. He "was born at Moulins in the Bourbonnais,

France, on August 21 1670. He was the son of Arabella Churchill

and James II. His mother was a daughter of Sir Winston Churchill,

descended from the Councils of Anjou, Poictou and Normandy. His

uncle was the famous John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough."

King James II prepared his son for a

military career. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which

deposed James, the King and his son fled to Catholic Ireland to

lead the resistance to Protestant English rule. There, the Duke

distinguished himself in battle and became acquainted with Patrick

Sarsfield and Master John Sullivan's father. He eventually married

Sarsfield's widow. After the failure of the Irish resistance, he

joined the French army as a volunteer, where he continued to

support the Jacobites [supporters of James II], and he again

distinguished himself, rising to the position of Marshal of

France.

Blunt family of Newcastle (45): Friends of Mary and the

Wallingfords who welcome them home. This passage from Charles

Hazlett, History of Rockingham County, New Hampshire

(1915), chapter 39 (placed on the Internet by Claudia Menzel),

gives a sense of the consequence of the Blunt family in

18th-century Newcastle:

Hon. John Frost and his lady were early

established at Newcastle, where he soon rose to eminence. He was a

member of his Majesty's Council, at one time commanded a British

ship of war, afterwards pursued the profession of a merchant, and

was much distinguished and highly useful in civil life. His place

of residence was on an eminence westerly of the Prescott mansion,

commanding a view of the spacious harbor, the river and its

table-lands, with the lofty Agamenticus in the distance. Some

remains of his extensive wharf may yet be traced. His family was

numerous and highly respectable, one of whom was Madame Sarah

Blunt, born in 1713, consort of Rev. John Blunt, third

pastor of the church in Newcastle, and after his decease the wife

of Hon. Judge Hill, of South Berwick, Me. Hon. John Frost died

February 25, 1732, in the fifty-first year of his age. In the

cemetery is a moss-covered monument, which bears unmistakable

evidence that the same poet who sketched the above chaste epitaph

has also, in as smooth and as strong lines, drawn another marked

portraiture : "To the memory of Rev'd JOHN BLUNT, Pastor of the

Church of Christ of this Town who died Aug. 7, 1748, in the 42d

year of his age, whose body lies here interred, this stone is

erected. "Soft is the sleep of saints, in peace they lie, They

rest in silence, but they never die; From these dark graves, their

flesh refined shall rise And in immortal bloom ascend the skies.

Then shall thine eyes, dear Blunt! thine hands, thy tongue -- In

nicer harmony each member strung -- Resume their warm devotion,

and adore Him in whose service they were joined before."

Bordeaux (23): A major fishing port in southwestern France.

Boston (2 and many others): in Massachusetts, a center of revolutionary activity.

Duke de Boufflers (16): This boy, who was a fellow-student of Voltaire (and according to this novel, of Master Sullivan) in Paris, probably was the grandson of the military hero who gained the title for his success as Marshal of France during the War of the Grand Alliance (1689-1697; see Voltaire, The Age of Louis XIV, Ch. 16). Parton's Life of Voltaire (in Related Materials) tells this story about the boy at the Collége Louis-le-Grand: "It was while Voltaire was a pupil that the Duke de Boufflers and the Marquis d'Argenson conspired with other boys to blow a pop-gun volley of peas at the nose of the unpopular professor, Father Lejay, and were condemned to be flogged for the outrage. The marquis, a boy of seventeen, the son of a king's minister, managed to escape; but the younger duke, though he was named 'Governor of Flanders' and colonel of a regiment, was obliged to submit to the punishment" (v. 1, 31-2).

Boutineaus (34): George A. Ward in Journal and Letters

of Samuel Curwen (1842) identifies James Boutineau (d. after

1777) as a Boston attorney, the "father-in-law of John Robinson,

commissioner of customs, who made a personal attack on James Otis,

Esq., [1725-1783] which produced so great a derangement of mind in

the latter, as to lead to his withdrawal from the public service"

(492-3, See also Sabine, American Loyalists, 168-9).

Of the Otis incident, Lossing says:

"The public career of Mr. Otis was ended before the tempest of the

Revolution which he had helped to engender, burst upon the

colonies. In 1769, his bright intellect was clouded by a

concussion of the brain, produced by a blow from a bludgeon in the

hands of a custom-house officer whom he had offended. Ever

afterward he was afflicted by periods of lunacy. At such times,

thoughtless or heartless men and boys would make themselves merry

in the streets, at his expense. It was a sad sight to see the

great orator and scholar so shattered and exposed" (Our Country

V. 2, Ch. 7).

Brest (21 and others): A major French port and naval base on the Penfeld River at the western end of the Breton peninsula. See Quiberon.

Breton coast (15 and others): The coast of Brittany in France. On a trip by sea from Nantes, a port in the mouth of the River Loire to Brest a port at the western tip of the Breton peninsula in France, one may sail along the southern coast of the peninsula. Paimbœuf and St. Nazaire are also in the mouth of the Loire, west of Nantes. Presqu'ile de Quiberon is a small peninsula about half way along this journey. Off the end of this peninsula is Belle Île (Belle Isle). Lorient (L'Orient) is a port west of Quiberon.

Bristol (2 and others): A major seaport in southwestern England, where the Lower Avon flows into the Severn and then into Bristol Channel. Research on the locations in the Bristol vicinity is by Graham Frater, who provides these acknowledgments: For help and guidance on gathering local evidence for the Bristol sections of the The Tory Lover, warm thanks are due to Mr John Penny of the Fishponds Historical Society (http://www.fishponds.freeuk.com/), Ms Madge Dresser of the University of the West of England, Mr and Mrs T. Ross [the owners of Old Passage House, Aust, formerly the Old Passage Inn), Ms Sheila Lang of the Bristol Records Office, Jan Wood, archivist of the Devon Records Office, Mr and Mrs R. Ebbs of Littleton-upon-Severn, Joy Coupe, Administrator at Bristol Cathedral.

The abbey church of St. Augustine (38)

in Bristol in the 18th Century would have been what

remained of the Abbey of St. Augustine.

The present Cathedral Church of the Holy and

Undivided Trinity was founded as St Augustine's Abbey in 1140. The

Chapter house and Abbey Gatehouse survive, as do several of the

side chapels, and the night stairs, but the uncompleted nave was

demolished when the abbey was dissolved in 1539. The remaining

portions of the abbey became the new cathedral (1542), or formed

parts of Bristol Cathedral School, next door. The cathedral was

further developed in the nineteenth century. See also:

www.bristol-cathedral.co.uk.

Since this was the site of the original abbey,

and since some of those original buildings remain, including the

gatehouse, (where Mary passed 'two forlorn Royalists' just before

she went in), it seems most likely that this is the church

referred to in the novel. However, there was also a church of St

Augustine the Less, of which Sheila Lang writes: 'Before the

creation of Bristol Diocese the Abbey of St Augustine was a major

landowner, situated in the city centre. At the Dissolution of the

monasteries by Henry VIII, all the lands and property of the Abbey

went towards the endowment of the new Diocese of Bristol in 1542.

Near the Cathedral stood the church of St Augustine the Less in

the 18th century. It was damaged in the blitz, and demolished in

the 1960s, and a hotel [the Swallow] now occupies the site."

Before he was translated to St Paul's in

London, The Reverend Sydney Smith (1771-1845), whose biography

Kate and Helen mention as a favourite in the last chapter of

Jewett's Deephaven, was a prebendary canon of Bristol

Cathedral. He was a prominent reformer, and the founding editor of

the highly influential Edinburgh Review. He mischievously preached

a sermon on Catholic toleration to the burghers of Bristol on 5th

November 1828 (Nov 5th is commemorated to this day with fireworks

to celebrate Britain's 'salvation' from Guy Fawkes's pro-Catholic

Gunpowder Plot, 1605 -- intended to blow up King and parliament).

Joy Coupe of the Bristol Cathedral points out that the

monument Mary views in Chapter 38 is the Newton monument in the

Newton Chapel. The parents shown died in 1599, so they died

in the reign of Elizabeth I, but the monument probably is

Jacobean. The parents, Ms Coupe points out, are lying down

rather than kneeling. The children are kneeling in the

height order described in the text.

Bristol Quay (33): Not a single quay, but a cluster of wharfs and quays in Bristol harbor, close to the city center. Sheila Lang writes: 'There are several quays within the city, as two rivers flow through the city centre, the Avon and the Frome. Broad Quay and Narrow Quay are still in existence, but the Quay itself is now known as Quay Street, and the river has been culverted in this area, so the Quay has gone; [the] reference to Bristol Quay could be to any of these."

Clifton Downs (32 and others): Clifton Downs is now a large public common, high above the city near to the University of Bristol, and Brunel's suspension bridge. The Downs still afford fine views of the city just as Davis suggests, and the Dundry Hills can be seen from there too.

Mr. Davis's house (33): The text suggests that this was close to the waterside, the wharves where the ships were unloaded, and the warehouses where their cargoes were stored. Bomb damage in World War II left few such merchants houses standing. If the house was indeed close to the quayside, it would have been only a short walk to Bristol Cathedral, (the Abbey Church of St Augustine).

Dundry (43): The Dundry Hills lie some six miles to the south of Bristol, and may be seen from several parts of the city, including Clifton Downs.

King or King's Road: King's Road: the stretch of water close to the village of Pill where the River Avon, (along which Bristol grew up), joins the Severn Estuary. From this point it was customary for the men of Pill to pilot ships into Bristol's wharves and docks (source: John Penny). Sheila Lang of the Bristol Record Office writes: "King Road and Hung Road are areas in the River Severn estuary, near to where the River Avon flows into the Severn from Bristol."

St. Mary Radcliffe (43): St. Mary Redcliffe (not Radcliffe) remains a sizeable and prosperous city church in Bristol. See also www.stmaryredcliffe.co.uk.

Burgoyne (6 and other chapters): The British general, John Burgoyne (1722-1792) was an important figure in the American Revolution. According to the Encarta Encyclopedia, he became dissatisfied with British conduct of the war; "he won official approval of his own campaign strategy to invade New York from Canada and combine his troops at Albany with a force of British and Native Americans under Colonel Barry St. Leger. In May 1777, Burgoyne replaced Carleton in command and in the early summer moved southward with almost 9000 men. He captured Fort Ticonderoga on July 6, but thereafter his advance toward Albany was slowed. He reached Saratoga in September, fought an indecisive battle with the Americans, and retreated. On October 7 he again made contact with the Americans at Saratoga but, lacking reinforcements and supplies, surrendered ten days later to Major General Horatio Gates. The American victory is generally regarded as the turning point of the war."

Butler's Hill: See Berwick.

C

[ Top of Page ]

Cæsar (2): A servant of Mary Hamilton's family. In Chapter 35, Cæsar is referred to as "their own old slave." See "Cæsar" in Extended Notes for more on slaves in Old Berwick.

Cambrai (17): An agricultural and industrial region, specializing in textiles in northern France, southwest of Lille, along the Escaut River. This is the town where Fénelon resided at his death, hence Master Sullivan's travels there with Fénelon's nephew, the Abbé de Beaumont: (Research assistance: Travis Feltman)

Cambridge (2): In Massachusetts, west of Boston, the location of Harvard College, now Harvard University.

Carrickfergus (27,31): In northeast Ireland, on the Belfast Lough, north of Belfast.

Carnac/Mont St. Michel (23): Carnac is a village near the Atlantic coast of Brittany (Bretagne) in northwestern France, famous for its prehistoric stone monuments known as menhirs and dolmens (sometimes associated with Druids), which seem to be linked historically to the nearby Mont St. Michel off the coast of Normandy. (Research: Travis Feltman; Source Encyclopedia Britannica Online)

Carsethorn Bay (2,6): The port town of Carsethorn in Scotland is down river from Dumfries on the River Nith, near J. P. Jones's birthplace at Arbigland.

Judge Benjamin Chadbourne (1): Benjamin Chadbourne (1718-1799), from one of the leading families of South Berwick, served as a soldier and politician as well as a judge. See Extended Notes.

Channel (12 and others): The English Channel, between England and France.

Duke and Duchess of Chartres (23, 39): Louis Philippe Joseph (1747-1793) was Duke of Chartres and then Duc d'Orléans, a French nobleman, cousin of King Louis XVI. See Extended Notes.

Chase, James (12): Jewett identifies him as an old Nantucket seaman, who served with Jones on the Alfred.

Abbé de Châteauneuf (17): According to Parton's Life of Voltaire, the Abbé de Châteauneuf was Voltaire's godfather and tutor. He is characterized as a freethinker and epicurean, and a lover of the dramatist, Racine (25). He recognized young Voltaire's talents and in various ways furthered his early successes, such as introducing him to influential patrons like Ninon de Lenclos, mistress of several powerful men, including the Abbé de Châteauneuf. (Research assistance: Travis Feltman)

Earl of Chatham (23): William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (1708-1778), was the prime minister of Great Britain (1766-1768) who led the country to victory over France in the Seven Years' War. He also was known for his defense of the rights of the American colonies at the beginning of the Revolution. (Source: Encarta Encyclopedia)

Monsieur Le Ray de Chaumont (22): Jacques Donatien Le Ray de Chaumont, says, S. E. Morison, "was a bourgeois who, after making a fortune in the East India trade, bought the sumptuous Hôtel Valentinois.... Having Dr. Franklin and the other Commissioners and their secretaries live on the grounds of his splendid residence was a convenient means for conducting Franco-American relations informally and discreetly." Morison also says that Mme. de Chaumont became Jones's mistress. (John Paul Jones123-5).

Chippenham (43,44): A town east of Bristol, in England.

Christian Shore (10): Now in northwest Portsmouth, N.H., across from the western part of Kittery, on the Piscataqua River.

Clifton Downs: see Bristol.

Collége Louis-le-Grand (17): A prestigious Jesuit school

in Paris, where Voltaire received his formal education during

1704-1711, and where Jewett says Master Sullivan studied in

France. No documentary evidence has been found to show that

Sullivan actually studied at this school, though it is clear he

received a fine education in France. Indeed, Parton's Life of

Voltaire suggests it is unlikely Sullivan could have

received an education in multiple languages at Louis-le-Grand,

which taught mainly Latin and a little Greek.

Click here to

see photographs of Louis-le-Grand.

Concord, Massachusetts (2,34): West of Boston, this town, along with Lexington, was the site of the first battle of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775.

Prince of Conti (3): See Duke of Sully.

Cooper (12): Cooper would appear to be an entirely

fictional character, though Cooper is a common name, and there

were many living in the Piscataqua region during the American

Revolution. Jewett identifies him and Hanscom as from the South

Berwick area. In 15, Cooper and Wallingford are said to be old

friends who share many memories, and Jewett identifies the

Wallingford servant, Susan, as Cooper's older sister.

An Alexander Cooper (b. 1746) resident in

South Berwick 1818, is listed as having served in the Revolution

in Fisher & Fisher.

Mrs. Craik (22): John Paul Jones's father worked as a gardener for William Craik, a landowner at Arbigland, Scotland.

Cranberry Meadow (9): A rural area east of Berwick, Maine; now it has become mainly woodland. See "The Old Town of Berwick" for a photograph.

Cuffee (8): Haggens family slave. See Cæsar.

Cumberland (6,24): Now part of Cumbria, Cumberland was a northern border county in England, divided from Scotland by Hadrian's Wall.

Judge Curwen (1,2,38): Samuel Curwen (1715-1802) was

American-born and a judge of Admiralty in the British colonial

administration of the American colonies, a loyalist with a complex

attitude toward his homeland, and an American refugee in England

from 1775-1784. See Extended Notes.

D

[ Top of Page ]

Lord Darwentwater (36): James Radcliffe, 3rd

Earl of Derwentwater (1689-1716), was a cousin and childhood

companion of James III (the "Old Pretender") and became involved

in the 1715 Jacobite uprising. He was captured and executed in

1716. His younger brother, Charles Radcliffe, led troops in this

rebellion. See Charles Radcliffe.

In a letter of 21 November 1901 to Roger L.

Scaife at Houghton Mifflin, Jewett requested a number of final

corrections to the novel text. Possibly because it was by

then too late for alterations, they were not made. One of

these was to change the spelling from Darwentwater to

Derwentwater.

Davis, John (32): Bristol (England) merchant; helper of Mary Hamilton and Mme. Wallingford. Almost certainly this is a fictional character, though the name of John Davis is common enough to appear in Bristol records of the 18th century that one finds on the Internet. However, no particular John Davis has been found on whom Jewett may have based her character. See Extended Notes.

Mr. Deane (22): Silas Deane (1737-1789), along with Benjamin Franklin served as an American commissioner to France during the Revolutionary War.

Denny Delane (30): Dennis Delane (1700-1750) was a celebrated Dublin and London actor, remembered for his parts in Elizabethan plays, such as Shakepeare's Henry V.

Dickson (12): He is said to be an officer in Ch. 24 and later, but which office is not specified. A Stephen Dickson is listed as an apprentice boy from Boston in Buell, but clearly this boy is not the model for Jewett's villain. Sawtelle lists no Dickson. However, it is possible that Jewett used this name because it was familiar to people in late 19th-century South Berwick, Samuel Dickson / Dixon. Samuel Dickson was a somewhat shady operator of a liquor shop in mid-century Salmon Falls. His shop is associated with an 1854 murder, in which Dr. Jewett examined the body, and he was involved in local conflict over prohibition of alcoholic beverage sales in Maine in the 1850s. He is remembered for identifying a group of arsonists who motivated, apparently, by their opposition to prohibition. (Research: Wendy Pirsig; for more information see http://www.obhs.net/Rum1.html.)

Dilston Hall (36): The seat of the Radcliffe family, until James Radcliffe, Earl of Derwentwater, was executed for treason in 1716, and his brother Charles was condemned, but escaped. Then the estate was confiscated and turned over to the Royal Hospital at Greenwich. The mansion, near Hexton, Northumberland, is now a ruin, but the chapel remains intact. (Research assistance: Graham Frater)

John Dougall (12): Dr. Green reports that a John W. Dangle was killed on 24 April 1778 in the capture of the sloop of war, Drake, near Carrickfergus, and Jones reports in his own narrative of the events that John Dougall died in the capture of the Drake (Sands 85).

Johnny Downes (12): Named as a ship's boy in The Tory Lover.

Dover (4 and others): On the Cocheco River in New Hampshire, Dover is about 10 miles northwest of Portsmouth. A farming and fishing village when originally settled at Dover Point in 1623, within two decades, there were sawmills along the river, beginning the town's history as a manufacturing center. Dr. Ezra Green, ship's doctor of the Ranger, is from Dover.

Dover Landing (4): Also known as Cocheco Landing, below the falls on the Cocheco River in what is now the town of Dover, NH. Gulf Road would have begun at Dover Landing in 1777.

Dover River (6): This is now the Cocheco River.

Dover Point (6): About 5 miles down the Cocheco from Dover, Dover Point is the site of the original settlement of Dover.

Garrison Hill (8): This high point in Dover was the site of several garrisons used mainly for defense against hostile Indians in the various Indian wars. From a tower on the hill one commands a view of the Salmon Falls/Piscataqua valley that includes the area from South Berwick to Portsmouth.

Research assistance: Wendy Pirsig. Sources: New Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State by the Federal Writer's Project (1938); Robert A. Whitehouse and Cathleen C. Beaudoin, Port of Dover: Two Centuries of Shipping on the Cochecho (1988).

Dublin (30): The capital of Ireland

Trinity College (30): Now the University of Dublin, founded by Elizabeth I in 1592.

Smock Alley Theater (30): Margery Sullivan remembers her father telling of the collapse of the gallery in this theater, which took place in 1672.

Dumfries (2): On Solway Firth in Scotland, on the River Nith, northeast of Arbigland, and north across the firth from Whitehaven.

Dundry: See Bristol.

E

[ Top of Page ]

Young Earl (31): Earl is mentioned once as imprisoned in the Mill Prison in Chapter 31, but he is not on Charles Herbert's list of prisoners. In the March of 1779, Jones helped to negotiate a prisoner exchange in which over 200 American prisoners were released. Many of these then joined Jones as crew for the Bon Homme Richard; John Earl is listed by the unreliable Augustus Buell as among the petty officers and able seamen on the Richard. See William Earl below for information about the Earl family.

William Earl (19): Acts as secretary for Captain Jones on the Ranger on the night that Wallingford notices Jones is wearing Mary's ring. Earl is not on Buell's list of the crew. According to the Chadbourne Family Association web site, the Hearl (sometimes spelled Earl) family had several members residing in the area of South Berwick during the era of the American Revolution.

Earl of Halifax Tavern: See Portsmouth.

Lord Mount Edgecumbe (34): George Edgecumb (1721-1795),

became 1st Earl of Mount Edgecumbe in 1789. He "was a naval

officer who saw a great deal of service during the Seven Years'

War. Succeeding to the barony on the 1st baron's death in 1761, he

became an admiral and treasurer of the royal household; he was

created Viscount Mount-Edgecumbe in 1781 and earl of

Mount-Edgecumbe in 1789." The family possessed estates near

Plymouth, notably the extensive residence at Mount Edgcumb, and

the first Earl also held the appointment of Lord-Lieutenant of

Cornwall.

In Chapters 34-7, he is said to be concerned

about his oaks going down, is criticized for his oversight of the

prison, and is said to be the master of Plymouth. None of

these assertions has yet been verified. (Research

assistance: Graham Frater; additional sources: Duprez's Visitor's

Guide to Mount Edgecumbe, 1871, "Historical Sketch of the

Edgecumbes" and L. Jewitt and S. C. Hall, The Stately Homes of

England.).

Eppin' (12): Epping, N.H. is about 15 miles west of Portsmouth on the Lamprey River. It is one of the oldest settlements in the state and was originally a part of Exeter.

Exeter (2,22): On the Exeter River in Rockingham County

about 10 miles southwest of Portsmouth, Exeter was the capital of

New Hampshire during the American Revolution. The town was notably

rebellious against British rule in the years preceding the

Revolution: "In 1775, the capital was removed to Exeter from

Portsmouth, there being too many Tories at Portsmouth, while

Exeter was almost wholly Revolutionary" (New Hampshire: A Guide

to the Granite State by the Federal Writer's Project, 160).

F

[ Top of Page ]

Mr. George Fairfax, of Virginia (35): The Fairfax family

were prominent Virginia landowners, and included, as well-known

loyalists, Lord Thomas, whose estate was thought to be the largest

in America at the beginning of the revolution, Bryan (1727-1802)

and George (1724-1787). Bryan and George were brothers, the sons

of Colonel William Fairfax.

George Fairfax was British born,

immigrated to Virginia and served in various official positions

until he inherited property in Yorkshire in 1773 and returned to

England to manage it. He did not return to Virginia. In American

Loyalists (1847), Lorenzo Sabine says:

"He fixed his residence at Bath....

During the war he evinced much kindness to American prisoners who

were carried to England. A part of his Virginia estate was

confiscated, by which his income was much reduced. Washington

esteemed him highly, and they were ever friends" (277).

Falls (12): A gunner who plays fiddle.

Dr. Green reports that James Falls was

wounded on 24 April 1778 in the capture of the sloop of war, Drake,

near Carrickfergus.

Falmouth, Maine (29,34): In 1787, the city name was changed to Portland. This was the site in 1775 of a British bombardment that burned the town. According to Amory in The Life of James Sullivan, the attack took place after Captain Mowatt, a commander under Admiral Greaves, was captured by American forces. He was released in response to a threat of bombardment, but "Irritated at the indignities to which he had been subjected during his detention and at the opposition manifested later by the inhabitants to a proposed supply of spars and other materials for the fleet, under the sanction of the admiral ... he bombarded and destroyed Falmouth" (I, 59-60). Amory reports that news of this attack on a civilian population spread panic through sea coast towns and villages from Falmouth to Boston. See also Williamson, History of the State of Maine, v.2, Chapter 16.

Faneuils (34): In Journal and Letters of ... Samuel Curwen, Ward describes Benjamin Faneuil as a Loyalist, "a merchant of Boston, and with Joshua Winslow, consignee of one-third of the East India Company's tea destroyed in 1773; was a refugee to Halifax, afterwards in England" (492). The Faneuil family had been prominent in Boston in the 18th century, Peter Fanueil building and giving to the city the famous Fanueil Hall, which became a noted meeting place of American rebels.

Fénelon, François de Salignac de la Mothe (17). Fénelon (1651-1715) was a French writer, theologian, and bishop. Having served as tutor to Louis XIV's grandson, the Duke of Burgundy, Fénelon was intimately connected with the French court, even after he fell out of favor with the king. He submitted to the Church's condemnation in 1699 of his Maxims of the Saints, and continued as Archbishop of Cambrai (1695-1715) - in exile from the court - until his death. He is well-remembered in part for his great acts of charity during the War of the Spanish Succession. (Sources: "Life of Fénelon," by Lamartine, in Fénelon, Adventures of Telemachus. O. W. White, editor, 1886; and Voltaire, The Age of Louis XIV, Ch. 38).

Joseph Fernal (12): Named as an old Portsmouth sailor.

Hezekiah Ford (41): One of Arthur Lee's private secretaries. Buell charges that he, like Thornton, was involved in revealing U.S. secrets to the British and in encouraging Lieutenant Simpson to mutinous actions (1;105, 2;43), but this has not been confirmed in reliable sources. Indeed, biographer Louis W. Potts in Arthur Lee (1981), says that Ford was not a spy, but that "Governor Patrick Henry and the Council of Virginia considered Ford an enemy to the American cause of independence," because he had opposed a militia draft in North Carolina and engaged in counterfeiting. Potts says virtually nothing is known of Ford's movements after he returned to the United States in August, 1779, on a mission to vindicate Arthur Lee of charges made against him by Silas Deane (222-3).

Fox, Charles James (23): Fox (1749-1806) was a "British statesman, one of the principal leaders of the Whig Party in the period of the American and French revolutions. The son of Henry Fox, 1st baron Holland, a Whig politician of the previous generation, Fox was born in Westminster on January 24, 1749, and was educated at Eton and the University of Oxford. He entered Parliament at the age of 19, obtaining a seat through his father's influence, and was initially a supporter of the Crown. He held minor posts in the ministry of Lord North between 1770 and 1774, until King George III had him dismissed because of his open sympathy for the American colonists. He then joined the Whig opposition and quickly became one of its leaders, showing great skill as an orator." (Source: Encarta Encyclopedia).

Benjamin Franklin (22):

Franklin (1706-1790) was a major figure in the American

Revolution. In addition to serving as a commissioner to France,

Franklin was an active revolutionary in a variety of other

capacities, including signing the Declaration of Independence and

serving as a delegate to the U. S. Constitutional Convention.

Click here for

images of Franklin's Paris.

French Minister of Marine (22): Antoine de Sartine

(1729-1801) was French Minister of Marine (1774-1780). He also

served as master of requests for the city of Châtelet, lieutenant

general of the police in Paris, and as state counselor. (Research:

Travis Feltman)

G

[ Top of Page ]

Gardner (23): a sailor on the Ranger.

Garrick (11): David Garrick (1717-1779): English actor, producer, dramatist, poet, and co-manager of the Drury Lane Theatre. He was best known for his roles as King Lear, Macbeth, and Richard III in Shakespeare's plays as well as Abel Drugger in Ben Jonson's The Alchemist. His reforms of the Drury Lane Theatre made him highly successful from the years 1747 to 1775. (Research: Travis Feltman)

Garrison Hill: See Dover.

George III (12): King of England during the American Revolution, George III (1738-1820) was determined to retain the American colonies and that they should submit to Royal rule.

Mr. Nicholas Gilman, of Exeter (2): Belknap in The History of New-Hampshire identifies Nicholas Gilman (1731-1783) as a counselor and then a senator from New Hampshire 1777-1783. He was treasurer of New Hampshire during the Revolution. His eldest son Nicholas (d. 1814) was a delegate to the second constitutional convention and also served as a senator from New Hampshire, and his second son, John Taylor (d. 1828) was governor of New Hampshire (262). His third son, Nathaniel, a New Hampshire state legislator, was Sarah Orne Jewett's great-grandfather on her mother's side. See also, Paula Blanchard, Sarah Orne Jewett (12). "Master Tate's Diary" gives the death of the wife of Nicholas Gilman (Sr.), Molly, 28 December 1777. Molly was the daughter of Rev. James Pike; this would suggest that Rev. Pike was Jewett's great-great-grandfather (See Parson Pike below).

General Goodwin (2):

In Chapter 2, he laments the decline of

law and order, referring to slavers, the minister guesses, and so

leading Jones to raise an issue over which the community is

divided. In Chapter 29, he leads in breaking up the mob that

attacks Mrs. Wallingford. This is General Ichabod Goodwin

(1743-1829) of Old Fields, grandson of Hetty Goodwin. See Extended

Notes.

Old Mrs. Hetty Goodwin (32): Mehetable Goodwin was one of the early settlers of Berwick, famous in the area for the story of her Indian captivity during the French and Indian wars. See Extended Notes.

Lord Gormanstown (30): The Lords Gormanstown, Howth, and Trimlestown are all remembered by Master Sullivan in Chapter 30 as fancy dressers when attending the theater in Dublin during Sullivan's youth, probably in about 1720. All three families were prominent among the nobility in Dublin in the 18th century. See Extended Notes.

Thankful Grant (4): Grant is a common name among the sailors who served with John Paul Jones, and there was a large Grant family living in South Berwick during the Revolutionary era. They intermarried with the Wentworth and Ricker families, among others according to John Wentworth, (1815-1888) The Wentworth genealogy: English and American. According to various family web sites, there was a Thankful Grant born in Westfield, MA in 1776, but the date and the distance suggest that Jewett was not thinking of this particular person as the young woman who fears for her "young man" who has joined the mob from Dover that plans to question Roger Wallingford about his loyalty in Ch. 4. "Thankful" also was a name known to Jewett, and probably would be associated in her mind with Quakers. See Mary Rice Jewett's "Recollections of Whittier," (in Biography) for Thankful Hussey.

Grant (12): probably Ephram, a sailor on the Ranger.

Gray (2): Harrison Gray (1712-1794), according to Ward, was a merchant and receiver-general of Massachusetts before the Revolution. Ward describes him as a particularly able, honest and faithful public servant who had the bad fortune to be appointed to the position responsible for tax collection for the Crown in 1774, shortly before Royal government ceased to command authority. Ward says, "Perhaps no man among the many excellent persons who went into exile at that time, was more beloved and regretted by his political enemies; for a more genuine model of nature's nobleman never lived" (Letters and Journals of ... Samuel Curwen 506-7).

Great Bay (1,6): Great Bay and Little Bay open into the Piscataqua estuary between Dover and Portsmouth, N.H.

Great Falls (9,16): Between present day Somersworth and

Berwick on the Salmon Falls River, just downstream from the

Highway 9 bridge. In the early 19th century, the village of

Somersworth was often called Great Falls, though according to

Peter Michaud, this was not the name of the village but of "the

Great Falls Mfg. Co., the textile factory that was developed on

its shores in the early 1820's. The prevalence of the name Great

Falls in the 19th and early 20th century stand as testimony to the

dominance and power held by the 'corporation.' The name "Great

Falls" slowly drops out of usage when the company folds in the

1920's." The falls themselves were used by various mills from

settlement through the 19th Century.

(Research Assistance: Peter Michaud and Wendy Pirsig)

Great Works: See Berwick.

Dr. Ezra Green (1746-1847), ship surgeon (13): After five years service in the American army and navy, Green became a merchant and public servant in Malden, Massachusetts. For details and pictures, see Diary of Ezra Green in Related Materials.

[John] Grosvenor (12): a sailor on the Ranger.

H

[ Top of Page ]

Old Master Hackett (12): Two Hacketts, William and James, were well-known ship-builders in Portsmouth, NH, prior to and after the American Revolution. See Extended Notes.

Major Tilly Haggens (1) and Nancy, his sister (8): Tilly Haggens (d. 17 August 1777), though Jewett pointedly gives him and his sister a French ancestry, was actually an Irish immigrant. So far as has been discovered, he had no sister Nancy, though his daughter Nancy became the owner of the Jewett house in South Berwick and sold it to Thomas Jewett, Sarah's great uncle, in 1839. See Extended Notes.

Haggens family servants named in the novel (all slaves)

(8)

Cuffee

Apollo

Phoebe

In Tilly Haggens's will, he bequeaths a Negro man "named Seaser" to his son, John, and "a Negro boy called Sandy" to his son Edmund.

Tilly Haggens's house: See Berwick.

Halifax (29,32): Halifax, capital of Nova Scotia, was founded as a military base in 1749. When the British army evacuated Boston in 1775, many of the Loyalist refugees went to Halifax, a center for Tory exiles. When the Golden Dolphin sails from Halifax, the ship becomes liable to capture by American privateers as engaged in trade with England.

Lieutenant [Elijah] Hall (24): Dr. Green reports that Lieutenant Hall and he signed a petition for the release of the imprisoned Lieutenant Simpson on 29 May 1778. Sawtelle notes that Hall's biography appears in G. D. Foss's Three Centuries of Free Masonry in New Hampshire (1972): "Lost sight of an Eye and taken prisoner in battle off Charleston, S.C. He returned to Portsmouth and married Elizabeth Stoodley, daughter of the owner of Stoodleys Tavern (moved to Hancock Street in Strawbery Banke Museum in 1964.) After the war Elijah purchased the tavern and made it his residence for the remainder of his life. He was elected to the state senate in 1807-09, the Governors council in 1809-17. Died June 22, 1830. Was an incorporator of the Portsmouth Savings Bank. The Halls had three sons who were all killed in the War of 1812."

Colonel Jonathan Hamilton (1): Jonathan Hamilton (1745-1802) was the builder of Hamilton House in South Berwick, ME. His wife, not his sister, was Mary Hamilton. Both were born near South Berwick. Hamilton became a prominent merchant and ship-builder after the American Revolution. See Extended Notes.

Mary Hamilton (1): Mary Hamilton (1749-1800) in history was Jonathan Hamilton's wife. She was born Mary Manning in the Pine Hill area north of South Berwick, where Master Sullivan was schoolmaster. See Extended Notes.

Mary Hamilton (imaginary portrait) by Marcia O. Woodbury

Hamilton family servants named in the novel

Caesar: see above.

Peggy (4)

Spinners

(28):

Hannah Neal

Phebe Hodgdon

Hitty Warren

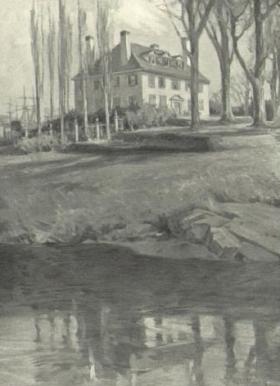

Hamilton House (1 and many other chapters):

See Chapter 1 for Photographs

This colonial mansion was actually built in 1785-88, after the

war, and restored during Jewett's lifetime. It overlooks the

Salmon Falls River in the southwestern part of South Berwick, once

known as the Lower Landing in Old Fields. There were wharfs,

stores, and warehouses at the Hamilton House landing site in the

1770s. Today the house and grounds are maintained by the Society

for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA,

http://www.spnea.org/visit/homes/hamilton.htm.) and open to the

public during part of the year.

Paula Blanchard in Sarah Orne Jewett

suggests that Jewett may not have known the date of the house's

construction, though by the time she completed The Tory Lover,

she had helped to arrange for Emily Tyson and her step-daughter,

Elise, to purchase and restore the property (See Alan Emmet, So

Fine a Prospect: Historic New England Gardens and the

Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities guidebook,

Hamilton House: a Quintessential Colonial Revival Summer House

in South Berwick, Maine. In "River Driftwood" (1881), Jewett

imagines John Paul Jones visiting the house (342).

Hamilton House by Charles H. Woodbury

Various sources affirm that David

Moore's mansion, which occupied the site before Hamilton House,

was equally impressive, but that it burned between 1777 and 1783.

The "gossipy" Goodwin Diary by Mrs. Ichabod Goodwin (Sophia

Elizabeth Hayes) from 1885 (Old Berwick Historical Society)

reports this as heard from Mrs. Raynes, July 31, 1884, "On the

place where the 'Hamilton House' now stands was a house built and

occupied by David More, which was burned, there was also another

large house built by Wm. Rogers ... nephew of Mrs. More. Both of

these houses were finer than the Hamilton House." She goes on to

report that the Rogers house was eventually moved without damage

to Portsmouth by gundalow. Even if John Paul Jones did not visit

Hamilton house itself, he could well have visited a similar house

at the same site. However, I have found no documentary evidence

that he traveled this far up-river from Portsmouth, where he

oversaw the completion of the Ranger.

The following in Cross-Grained &

Wily Waters, edited by W. J. Bolster (2002) draws upon

Marie Donahue in "Hamilton House on the Piscataqua," Down East

(1975): "During the American Revolution, Jonathan Hamilton

of South Berwick went privateering and amassed a fortune. With

peace he purchased thirty acres of land along the eastern shore of

the Salmon Falls River from Woodbury Langdon. There, on a high

bluff, Hamilton built a Georgian-style mansion in 1785 that, he

boasted, would be a 'finer house than Tilly Haggens's'...." (178).

In the opening chapters, Jewett refers

repeatedly to the sound of a nearby falls, giving it significance

as a voice of Nature that speaks to Mary and Roger of things that

seem more serious than the gay party that opens the novel. At that

time, the nearest falls of any size would have been where the

Great Works River flows into the Salmon Falls River; today this is

dammed to form Leighs Mill Pond.

In contemporary Berwick, falls are

difficult to hear in the busy village, except perhaps at the Upper

Landing, but in earlier days, it was apparently different. For

example, this is a letter of June 20, 1900 to Mrs. Henry Parkman

from The Letters of Sarah Wyman Whitman (pp. 126-7): "All

the stars are shining in this quiet town and peace lies like a

mantle over the hill. The rivers which gird in South Berwick have

seven falls within a mile, and a sound like that of some

mysterious sea comes on the air; and after you know, you always, a

little, hear it, and there are many things here which give a sort

of mystic quality to this old simple New England village."

In Chapter 28, Peggy at Hamilton House

looks up the fields to a row of elms at General Goodwin's house

and watches traffic on the Portsmouth Road. See General Goodwin on

the list of People. The Portsmouth road is now known as Oldfields

Road.

(Research assistance: Wendy Pirsig).

Hampton Roads (4): A channel in southeast Virginia between the mouth of the James River and Chesapeake Bay. Though Jewett follows Augustus Buell in having J. P. Jones meet Kersaint at this location, there is no evidence this meeting ever took place.

John Hancock (2): John Hancock (1737-93) was the first signer of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. In 1775-7, as presiding officer of the Second Continental Congress, he was called President Hancock. He chaired the Marine Committee during the American Revolution, and he was the first governor of Maine under the Constitution of the Commonwealth (1780-1785). He also signed the incorporation papers for the Berwick Academy. (Research assistance: Wendy Pirsig.)

[Reuben] Hanscom (12): Jewett indicates that he is a "river" man, like Cooper, from the South Berwick area. Fisher & Fisher list a Reuben Hanscom (1754-1831) who enlisted at Kittery, who married Lucy and then Alice, and who died in North Berwick (337). There is no indication that this Reuben Hanscom served on the Ranger.

David Hartley (22): Son of the philosopher David Hartley, Hartley studied medicine, became a noted scientist and a friend of Benjamin Franklin (See Chapter 22). He served in the British Parliament during the American Revolution and was associated with the Rockingham Whigs. He developed an expertise in finance and opposed British war policies during the Revolution. In "Letters on the American War" (1778), he argued for accepting American independence and pursuing friendly policies toward the new nation.

Charles Herbert, of Newbury, in Massachusetts (31): Jewett presents him as a scribe at the Mill prison. He is sometimes said to be from Newburyport. Herbert (1757-1808) is remembered for his narrative of his experiences when the American privateer on which he served, the Dolton, was captured and its crew imprisoned at Plymouth. In A Relic of the Revolution: Containing a Full and Particular Account of the Sufferings And Privations of All the American Prisoners Captured on the High Seas, and Carried into Plymouth, England, During the Revolution of 1776;With the Names of the Vessels taken -- the Names and Residence of the several Crews, and time of their Commitment -- the Names of such as died in Prison, and such as made their Escape, or entered on board English Men-of-War, until the exchange of prisoners, March 15, 1779 (1847), Herbert narrates the capture of the Dolton in December 1776 and tells of his experiences as a captive in the Mill Prison at Plymouth. His narrative contains the details Jewett presents about him, including his falling ill with smallpox. Herbert later served under John Paul Jones on the Alliance (1779-80). This book is available on-line at http://www.americanrevolution.org/relic.html.

Hertel and his French and Indians (16, 32): François

Hertel (1642-1722), was a French-Canadian. He and his sons

eventually served the French military in a series of raids on

English colonies during several periods of warfare. In 1690, in

King William's War (1689-1697), Hertel led Indian warriors into

Maine and New Hampshire. In this raid, Mehitable Goodwin was

captured and taken to Canada (see Chapter 32).

See Extended Notes and Photographs for Chapter 16.

Major Hight (8): Tilly Haggens notes Major Hight's new house on a ridge visible from the front porch of his house. Though it is difficult to be sure who this Major Hight is, the most likely candidate is William Hight, father of Temple Hight. See Extended Notes.

Midshipman [Benjamin] Hill (26): Buell lists Charles Hill

of Barnstable as a midshipman, and notes that he also served with

Jones on the Providence and the Alfred (1;51).

Buell also says that Hill authored "The Song of the Ranger" quoted

in Chapter 12, but S. E. Morison indicates that Buell made up this

document (427). Sawtelle lists Benjamin Hill, but not his

position.

Dr. Green says that Mr. Hill accompanied

Lieutenant Wallingford in the Whitehaven attack. Sawtelle lists

Benj. Hill, and S. E. Morison points out that during the

Whitehaven attack, Benjamin Hill, a friend of Jones, also was

serving as a volunteer officer on the Ranger (119).

Mr. Hill (2): Jewett may be referring to either of two John Hills of South Berwick. See Extended Notes.

Martha Hill (5): A young woman friend of Mary Hamilton; she is among the young people who attend the party for Jones the day before he sails. No record of a Martha Hill fitting this description has been found in the South Berwick area of this period.

Humphrey Hodgdon (28): This is one of the local men mentioned as killed in New Jersey battles of 1778 (Ch. 28). Hodgdon/Hodsdon is a prominent name in Maine, in which a county and a town are so named. However, it has not been confirmed that a specific Hodgdon from Berwick died in the Revolution. He is not listed in Fisher & Fisher. W. D. Spencer's "A List of the Revolutionary Soldiers of Berwick" (1898) lists Daniel Hodsdon as serving nine months in 1778, and being a prisoner.

Sir William Howe (32): William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe (1729-1814), according to the Encarta Encyclopedia was "British commander in chief in North America (1775-78) during the early years of the American Revolution. See Extended Notes.

Lord Howth (30): See above, Lord Gormanstown. The Howth

family name is St. Lawrence; Howth Castle remains a landmark in

Dublin. Samuel Fitzpatrick in Dublin: A Historical and

Topographical Account of the City (1907) give this

description from the 1780s:

"The North Circular Road now became a

fashionable driving resort, where the beautiful Duchess might be

seen in the magnificent viceregal equipage. Here, Lord Cloncurry

tells us in his Personal Recollections, 'it was the

custom, on Sundays, for all the great folk to rendezvous in the

afternoon, just as, in latter times, the fashionables of London

did in Hyde Park; and upon that magnificent drive I have

frequently seen three or four coaches-and-six, and eight or ten

coaches-and four passing slowly to and fro in a long procession of

other carriages, and between a double column of well-mounted

horsemen.'

"Here O'Keeffe saw Lord Howth with 'a

coachman's wig with a number of little curls, and a three-cocked

hat with great spouts,' while the 'horsey' character of the St.

Laurence family was further evidenced by the 'bit of straw about

two inches long' which his Lordship carried in his mouth" (Chapter

6).

Solomon Hutchings (13): Named by Jewett as the first victim of voyage -- a broken leg; This also is in Buell (1;86), but not, as one would expect, in the Diary of Ezra Green. Sawtelle notes that Solomon Hutchins "came down with smallpox, recovered" (194). Fisher & Fisher list Solomon Hutchins (b. 1760) as a navy sailor from Kittery serving on the Ranger (400).

Thomas Hutchinson (10): Hutchinson (1711-1780) was

the last civilian Royal Governor of the provinces of Maine and

Sagadahock (1769-1774). He was replaced by a military

governor-general, Thomas Gage, in 1774, who was soon replaced in

1775 by a rebellious Provincial Congress. Born in Maine and a

graduate of Harvard (1727), he was the author of a respectable

history of the Massachusetts colony. Williamson in The History

of the State of Maine says, "Not succeeding in his

commercial pursuits, though it seemed to be the most ardent desire

of his soul to acquire wealth; he applied himself indefatigably to

the study of history, politics and law. He was early elected by

the inhabitants of Boston into the House of Representatives, and

in 1747, he was Speaker. By his industry, eloquence, and knowledge

of public affairs, he acquired great influence and distinction.

Besides being Lieutenant-Governor he was a Councillor, Chief

Justice of the Superior Court in 1760, and also Judge of Probate

for Suffolk" (v. 2, ch. 13). As a former Royal Governor,

Hutchinson was sympathetic to Tory refugees in England.

J

[ Top of Page ]

Irish Sea (12,23,30): Between England and Ireland.

Island of Guernsey (41): One of the British Channel Islands, at the west end of the Channel, south of Bournemouth in England.

Isles of Shoals (7 and other chapters): Off the coast of New Hampshire, near Portsmouth, these islands are divided between Maine and New Hampshire. See Williamson for a description.

King James (3): James II (1633-1701), King of England 1685-1688. He was deposed in 1688 and replaced by his daughter, Mary II and her husband, William of Orange (William III). James's Catholic son, Francis Edward Stuart became the Old Pretender, James III, whom Irish and French Catholics, among others, wished to make King of England. James II's grandson, Charles Edward, became known as the Young Pretender.

Mr. Jenkins's (8): An 1805 survey map, at the Old Berwick

Historical Society, of part of the village of South Berwick shows

a Junkins house across the road (east side) from the John Haggens

house, and just south of this house a store is shown. This may

have been the store of Mr. Jenkins that Tilly is curious about in

Chapter 8, but this has not been confirmed.

The store on this map would be almost

directly in front of Haggens, and seems to correspond to the

location of Jewett's grandfather's West India store, opened after

Captain Jewett came to South Berwick around 1819-1821.

The Old Berwick Historical Society has

identified Jedediah and Jerusha Jenkins / Junkins as the owners of

an orchard on property at 105 Portland Street, up the street to

Tilly's left as he sits on his doorstep. Jedediah Jenkins

(1767-1852) would have been somewhat young to own the orchard and

business in 1777, but Jewett may have shifted him in time, or

perhaps she refers to his father. For more information see

the Old Berwick Historical Society web site:

http://www.obhs.net/2e.html.

John Paul Jones, Jr.: Captain of the Ranger.

John Paul Jones (1747-1792) was an

American naval officer during the Revolutionary War. He was born

John Paul on July 6, 1747, in Kirkcudbright, Scotland. He began

his sailing career at the age of 12 as a cabin boy, and served on

a slaver and then as captain of a merchant ship. According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1773, as commander of a

merchant vessel in Tobago in the West Indies, he killed the leader

of a mutinous crew. Rather than wait in prison for trial, he

escaped from the island and later returned to Fredericksburg,

[Virginia]. The British thereafter considered him a pirate and a

fugitive from justice. To hide his identity he added the surname

Jones." At the beginning of the American Revolution, Jones joined

the Continental navy. Britannica says "He was commissioned

a lieutenant and attached to the first American flagship, Alfred.

In 1776 he was promoted to captain and given command of the sloop

Providence. During his first cruise on the Providence

he destroyed the British fisheries in Nova Scotia and captured 16

British prize ships. In 1777 he commanded the sloop Ranger,

and after sailing to France, he cruised along the coast of

Britain, destroying many British vessels." See More Materials on

John Paul Jones, for materials available to Jewett and for

illustrations.

John Paul Jones

from Molly Seawell, "Paul Jones," 189

K

[ Top of Page ]

Kendal (27): Between Carlisle and Liverpool on the west coast of England.

Keays (16): In the histories of Maine, this name is sometimes spelled "Keys." This family is listed in Chapter 16 among those who were early settlers in Berwick and who had members captured by Indians and taken to Canada. See Hetty Goodwin in Extended Notes.

Kersaint, the French commodore (14): Buell reports a meeting at Hampton Roads, Virginia, of John Paul Jones and Capitaine de Vaisseau de Kersaint, the senior officer of two French frigates - one of which was the new Le Terpsichore - in May 1775. The Duke of Chartres was second in command. According to Morison, this meeting never took place (426).

Hate-Evil Kilgore (8): This child is an unfortunate South Berwick neighbor of Major Haggens, from down the Landing Hill, whose name reflects the ideas of "Roundhead days," the Puritan revolution in England (Ch. 8). Though the historical existence of this person has not be verified, Internet accounts of Kilgore and Brackett family history indicate that the Kilgore family had a branch in Kittery during the revolutionary period. John Kilgore came from Scotland before 1764 to live in Kittery, Maine; there he married Elizabeth Brackett in 1756. Their son Samuel was born in 1777. However, no Kilgores are buried in South Berwick cemeteries. See "Barebones" above.

Kittery (6 and other chapters): A coastal Maine town just across the Piscataqua River from Portsmouth, N.H.

Kittery Point (7): East of Kittery, across the

mouth of the Piscataqua from New Castle. In Kittery Point stands "Sir

William Pepperrell's stately gambrel-roofed house." The

William Pepperrell home, built in 1682, is an imposing house on

Pepperrell Cove. Piscataqua Pioneers (2000) says, "The

Pepperell Mansion should not be confused with the Lady Pepperell

Mansion ... which was built by Lady Mary Pepperell in 1760 aft.

the death of her husband, Sir William Pepperell" (337). Sir

William, hero of the capture of Louisburg during King George's War

in 1745, was the son of Colonel William Pepperell, builder of the

Pepperell Mansion. See Cross-Grained and Wily Waters

(2002), pp. 190-92.

L

[ Top of Page ]

the Lake (9): Mrs. Wallingford says men are coming down

from the Lake, which requires that she fill in for her absent son

in managing the estate. What lake this is is not clear, though

local historians speculate that Lake Winnepesaukee in New

Hampshire is the most likely location, noting that most nearer

bodies of water were called ponds, and that the more northerly

Maine lakes were not important sources of lumber for the

Piscataqua mills and ship-building in the 18th Century.

For example, Robert A. Whitehouse and

Cathleen C. Beaudoin" in Port of Dover: Two Centuries of

Shipping on the Cochecho say: "In 1824, a local [Dover]

group was formed to petition the State Legislature for two major

[Cochecho] River improvements: first the digging of a canal from

Dover to Lake Winnepesaukee so that trade routes could be

facilitated to the north country,...The prohibitive $700,000

estimated cost of such a canal led quickly to the demise of that

idea..." (17).

(Research assistance: Paul Colburn, Brad

Fletcher, and Wendy Pirsig).

Colonel John Langdon: (5,22): Langdon (1739-1819), of

Portsmouth, N.H., served in the American revolutionary army and in

the Continental Congresses. He was navy agent in 1776 and used his

own wealth to help outfit the army. After the war, he served in

the Constitutional Convention, and then as a United States senator

-- administering the oath of office to Presidents George

Washington and John Adams --, and as governor of New Hampshire.

His cousin, Samuel Langdon, also was an active revolutionary.

Sources: Amory, The Life of James Sullivan and New

Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State.

S. E. Morison reports that Jones and

Langdon got along badly because of the difficulties in outfitting

the Ranger (106-111).

Langdon's Island (12): According to The Diary of Ezra

Green, the Ranger "was built 1777, on Langdon's

Island, Portsmouth Harbor, by order of Congress, under the

direction of Colonel James Hackett." Jewett presents the same

basic information. John Langdon was a governor of New Hampshire

and the first president of the United States Senate.

This island's name proves somewhat

problematic in the novel, however. In Ch. 29, Madam Wallingford

refers to Badger's Island as the embarkation point for the

Golden Dolphin, and according to New Hampshire: A Guide to the

Granite State, the Ranger was built on Badger Island

(236). In fact, Langdon's and Badger are the same island.

Williamson in The History of the

State of Maine lists the following Islands in the Piscataqua

river as one enters Portsmouth from the north: "On the N. and E.

side of the channel, in proceeding to the sea, are Rising

Castle, Furnall's or Navy, Seavey's, Bager's Trefethin's,

and Clark's Islands, all of which are small except

Seavey's, which lies opposite Spruce creek and may be 3-4ths of a

mile across either way; and Furnal's, or NAVY ISLAND of 58 acres,

which has been purchased by the United States ... for a ship-yard,

in which several war ships have been already built" (v. 1,

Introduction). In New Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State

by the Federal Writer's Project (1938), Badger's Island is

identified as the site of "the earliest shipbuilding in

Portsmouth" (244).

It appears that during the Revolutionary

War, the island was called Langdon's Island, the location of

Langdon's shipyards. The most illustrious of William and James

Hackett's apprentices was William Badger (d. 1829), who apparently

married into the Rice family (see Rice's Ferry) and eventually

built ships at the Langdon Island shipyards. Ray Brighton in Port

of Portsmouth Ships and the Cotton Trade (1986) suggests

that the island was renamed for William Badger (146). In Piscataqua

Pioneers, Sylvia Getchell says the island was originally

Wither's Island, then Berry and Langdon, before becoming Badger

(11).

Today, one finds Badger Island at the

eastern end of the Memorial Bridge connecting Portsmouth and

Kittery; the island is bisected by Route 1. It remains the site of

a boatyard, though now for yachts and lobster boats instead of

ocean ships.

(Research Assistance: Wendy Pirsig)

Lebanon (8): A town in Maine on the Salmon Falls River, northwest of Berwick. James Sullivan says this town was originally Tow-woh (264). See also Williamson (v. 2, ch. 6). As Haggens says in Chapter 8, the town's name is in the process of changing from Tow-wow in the 1770s. Now there are several towns in the area, with Lebanon as part of their name. Colonel Hamilton's lumber interests in this area take him about 10 miles north from South Berwick.

Arthur Lee (22): The Encarta Encyclopedia

identifies Lee (1740-92) as an "American statesman and diplomat,

born in Stratford, Virginia. In 1766 he began the study of law and

became interested in politics. As a secret agent of the

Continental Congress in London during the American Revolution, he

negotiated with several European governments and helped conclude a

treaty with France. He served in the Virginia assembly in 1781 and

in the Continental Congress from 1782 to 1785." In Chapter 19,

Jones makes an enemy of Lee, one of the U.S. commissioners to

France, by expressing his anger at the loss of L'Indien,

and he comes to suspect that Lee is in private contact with

Dickson.

Buell says that Arthur Lee was surrounded

by British spies in his employ. He names Ford and also Stephen

Sayre, saying they betrayed U.S. secrets and manipulated Lee to

Britain's advantage (1;97-103 and 2;43). Jones learned some of

these facts shortly after arriving in France in 1777, when he

investigated Lee's charging Jones's friend Dr. Edward Bancroft

with using knowledge in secret dispatches for personal profit.

Jones's distrust of Lee apparently began early and grew during his

time with the Ranger (Buell 1;88-90).

Buell asserts that Ford, Thornton, and

Sayre were active in disrupting the activities of Jones and the Ranger,

notably in encouraging Lieutenant Simpson to mutinous behavior

that nearly led to his court-martial (Buell 1;130-40).

While this version of events corresponds

with Jewett's, it is not fully confirmed by other biographers and

historians. Morison sees Lee as mentally unbalanced and a bitter

enemy of Jones, and his view of Stephen Sayre is similar, but

neither is described as a traitor or spy. He affirms that Dr.

Bancroft - Benjamin Franklin's confidential secretary - was,

indeed, a spy. Nor does Morison discuss a connection between Lee

and Lieutenant Simpson (See Chapter 7. See also Evan Thomas,

Chapter 5).

Lee (2) An officer Jewett says General John Sullivan replaced on Long Island. The Battle of Long Island took place in 1776. General Charles Lee (1731-1782) was second in command of the Continental Army when he was captured by the British late in 1776. He remained a prisoner until 1778. After his capture, according to Jewett, General John Sullivan replaced him. The Treason of Charles Lee, George H. Moore's revelation that General Lee betrayed the Americans after his capture, appeared in 1858. (Source: Encarta Encyclopedia).

Leith (25): The old port of Leith in Scotland has been absorbed into Edinburgh.

Lejay (17): In his Life of Voltaire, James Parton says: "In a large school there must be, of course, the unpopular teacher, who is not always the least worthy one. Father Lejay, professor of rhetoric of many years' standing, filled this 'rôle' in the Collége Louis-le-Grand. He was a strict, zealous, disagreeable formalist; 'a good Jesuit,' devoted to his order, who composed and compiled many large volumes, still to be seen in French libraries; a dull, plodding, ambitious man, with an ingredient in his composition of that quality which has given to the word Jesuit its peculiar meaning in modern languages." Parton goes on to tell of a famous "collision" between Voltaire and Lejay, in which Lejay is supposed to have said to young Voltaire: "Wretch! You will one day be the standard-bearer of deism in France" (37-9)!

Lexington, Massachusetts: See Concord, above.

Little Harbor: See Portsmouth, N.H.

London (2 and many other chapters): The capital of

England.

Covent Garden (30): Now called

the Royal Opera House, this theater in London was opened on Bow

Street in 1732. The area of Covent Garden was originally a convent

vegetable garden, and in 1632 was designed as a garden by Inigo

Jones. (Source: Encarta Encyclopedia).

Long Island (2,9): The island east of New York City, where several important battles of the American Revolution were fought, notably the Battle of Long Island, in August 1776.

Billy Lord (28): Jewett lists him as local man killed in

New Jersey battles of 1778.

Whether Jewett had in mind a specific

William or Billy Lord is difficult to determine. The Lord family

web site offers these possibilities. William Wentworth Lord (b.

1761, m. Mary Allen in September 1783 Vital Records) of

South Berwick, was the son of Ebenezer and Martha Lord. William