Citizen, Merchant, Community Leader:

A New Interpretation of Jonathan Hamilton

By Margaret Kugelman Hofer

Yankee Intern

August 20, 1986

Copyright © 1986 by Margaret Kugelman Hofer

Reprinted by permission of the author.

Margaret Kugelman Hofer is Curator of Decorative Arts

The New-York Historical Society

No portion of this document may be reprinted without the

author's permission.

Originally submitted to

Susan Devito

Site Administrator

Hamilton House

Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities

Jonathan Hamilton as Community Leader

Jonathan Hamilton as Merchant and Ship Owner

Jonathan Hamilton as the Well-Connected Portsmouth Businessman

Epilogue: The Downfall of the Hamilton Family

Appendices

1. Genealogy of the Hamilton Family

2. Woodbury Illustration of Hamilton

House

3. Map of the Piscataqua Region

4. Tax Valuations of Berwick

5. Jonathan Hamilton's Vessels

6. Destinations of Jonathan

Hamilton's Vessels

7. Map of Portsmouth, 1813

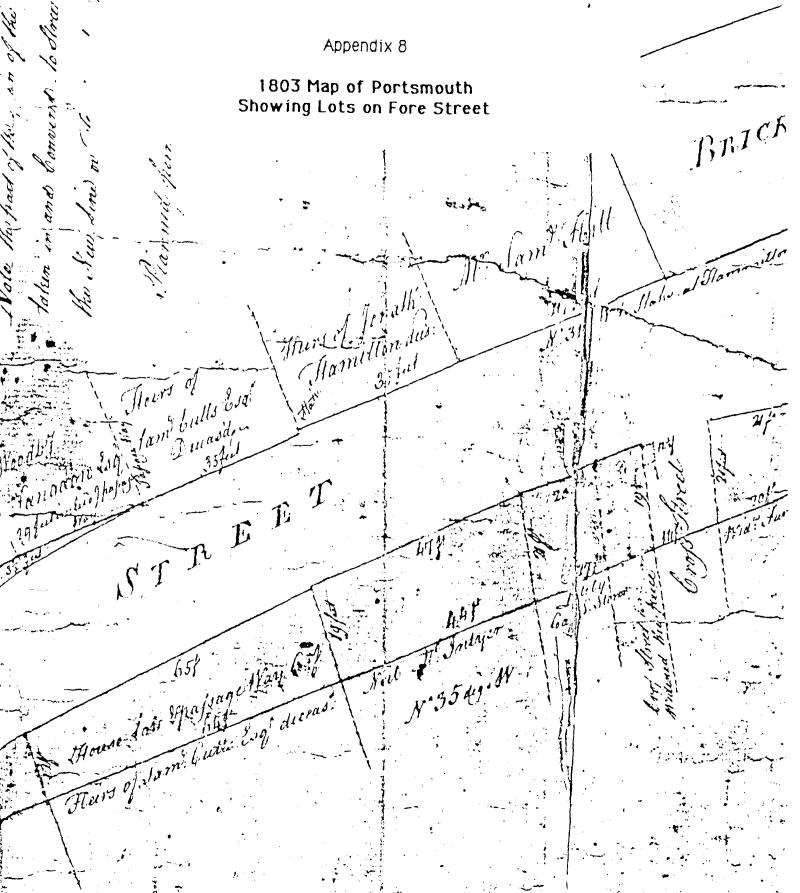

8. 1803 Map of Portsmouth and map of Hamilton

Property in South Berwick

9. Advertisement from the New

Hampshire Gazette - 1802

10. Advertisement from the New

Hampshire Gazette - 1801

11. Jonathan Hamilton's Obituary

12. Jonathan Hamilton's Epitaph

Introduction [Contents]

The following paper is the result of ten weeks of research on Jonathan Hamilton and the Piscataqua River network. The project originated as a study of the activity on the Salmon Falls River during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as a way to gain a better understanding of the history of Hamilton House. Over the ten weeks the project has evolved according to the nature of my discoveries, and it has concluded as a more in-depth study of Hamilton the man. Once I determined that Hamilton's center of business was actually down the river in Portsmouth, I shifted the focus of the project to concentrate on the various aspects of Hamilton's business, rather than just concentrate on what went on in the vicinity of the Hamilton House.

I have chosen to represent several aspects of Hamilton's life which I believe are most crucial to gain an understanding of the man. Each of the three major sections of the paper describes an aspect of Hamilton's daily life, or rather a role that he filled in society: merchant and ship owner, a community leader, and a well-connected businessman. Although these categories interconnect in many ways, they all describe separate but equally important aspects of Hamilton's career.

It has become clear through my research that Hamilton stood as a central figure not only in Berwick, where he lived, but also in Portsmouth, where he operated his business. The Piscataqua River served as the means of transportation between these two communities, but even more, it provided the commercial and social means for connection between both towns. The River, therefore, is crucial to the understanding of Hamilton's ease of movement between Portsmouth and Berwick.

This paper includes research to date;

it is an open-ended project with an unlimited amount of material

to be covered. Many questions still remain unanswered, and some

may never be answered fully. The scarcity of materials on

Hamilton himself necessitated the use of related information,

perhaps not directly pertinent to Hamilton. I have formulated

some theories based on this general evidence, and these may hold

a personal bias. This paper represents my interpretation of the

materials I consulted, but others may find that the same

evidence described another sort of man than the one that I have

portrayed. Hopefully, more research will be done on Jonathan

Hamilton, to fill in the holes that I have left, and to provide

further insights into his life.

Jonathan Hamilton as Community Leader [Contents]

Although Jonathan Hamilton grew up in a poor farming family, he rose to become one of the Berwick's most prominent citizens by the time of his death. Hamilton was born and raised in Berwick, as all of North Berwick, South Berwick, and Berwick was called until 1814.(1) Hamilton's father, Joseph, was a yeoman, and Jonathan was also referred to by this title until the age of 29, when he was conferred the title of gentleman.(2) It was about this period, the same time that revolution was becoming an issue in Berwick, that Hamilton began to take action as a community leader.

Various documents indicate the active role that Hamilton began to assume in Berwick affairs. On July 18, 1774, residents of Berwick got together to offer assistance to the people of Boston: "We the subscribers taking into consideration the Distressing Condition of the Town of Boston & the Poor in that Town in Particular by reason of their port being shut up -- We do promise such are of us to pay or Deliver…the cash or article affixed each of our names…"(3) One of the first names on this list is Jonathan Hamilton's, who agreed to give "1000 Bords".(4) One year later, on June 12, 1775, Hamilton's name appears among the list of members of the Committee of Correspondents who voted to petition the Provincial Congress for one or more companies for defense of the region.(5)

In these early years of revolutionary sentiment, Hamilton appears to be involved in matters on land, rather than at sea. Although he owned two privateers, one in 1780 and one in 1784,(6) (see discussion of his privateers in Portsmouth section) Hamilton's actual service was land based. Jonathan Hamilton was commissioned a Captain in the 2d York County regiment of the Massachusetts militia in April, 1776.(7) He was appointed to command men raised to reinforce the Continental Army that same year, but little else is known about his military service. Although he was a Captain in the revolution, Hamilton was always later referred to as a Colonel, which some believe to be a self-appointed title.

Beyond his military service, Hamilton was also involved in other public affairs. He was a religious man (see appendix 12), and was a member of the Old Fields Meeting House, which stood just down the road from his mansion. The Old Fields Meeting House was built in 1700, but remained unfinished for many years. Later, "the work was completed under the supervision of Col. Jonathan Hamilton, Judge Benjamin Green and others; and it was known as one of the finest wood-churches in New England."(8) Many important Berwick families besides the Hamiltons belonged to the Old Fields Congregation, including Judge Chadbourne, Dominicus, and Ichabod Goodwin, John Haggens, and John Lord.(9)

Hamilton's involvement in Berwick also extended to the sphere of education. In 1791, Col. Jonathan Hamilton became one of the founders of Berwick Academy, the "oldest literary incorporated institution in the state."(10) Hamilton is called the richest founder of Berwick Academy, and even became its first secretary and treasurer,(11) but it is unclear whether it was his money or his inspiration which was more important in starting the school. Hamilton himself had only a rudimentary education, and there is no evidence that he sent any of his children away to school.

Although he was involved with the religious and educational aspects of his community, Jonathan Hamilton's greatest contribution to Berwick was his business and the wealth it created. Numerous deeds indicate that Berwick residents often came to Hamilton to take out a mortgage on their property. Because of his business Hamilton probably had the biggest cash flow in the town, which would make him the most likely person to whom one might go for a loan or mortgage. It is unclear whether Hamilton operated in an official capacity when he acted as creditor, or whether these were personal favors done for friends. Although he may have been generous, Hamilton expected to receive the money or services rightfully due to him. Two cases appear in deeds which indicate Hamilton brought down the law upon debtors, and another one describes his prosecuting the owners of a grist mill when the services he paid for had been withheld.(12) Some deeds also reveal generosity on Hamilton's part. Hamilton was on a committee which was appointed at a town meeting to sell a piece of land to Enoch Chase, a shipwright, for 10 pounds.(13) This land, worth considerably more, lay on the river north of Hamilton's house. Chase would have been unable to purchase the land without the aid of Hamilton's committee, which lowered the price so that he would be able to afford it.

Besides aiding Berwick with his available money, Hamilton also supplied many of the people in Berwick with opportunities for work. Hamilton's business had many facets, all requiring labor. The goods that Hamilton exported probably came from Berwick farmers and landowners: timber, fish, beef, and other farming products. Wood products from inland such as masts, spars, planks, and shingles were the biggest export of the region. Hamilton needed people to fell the trees, haul the wood to the saw mills by the river, and finally load them on gundalows for the trip down to Portsmouth, where they would be loaded onto his trading vessels. With an unlimited supply of timber inland, Berwick residents were never far from a good source of income.

The building of Hamilton's mansion between 1785 and 1788 also would have employed a large work force. Although he probably hired skilled craftsmen from Portsmouth to do the fine carving, Hamilton would have also used local labor for more basic jobs such as providing timber, preparing it at his saw mill, and doing simple construction. There would have been labor needed to transport all of Hamilton's belongings from Pine Hill, as well as people to bring furnishings and other items upriver which Hamilton had acquired in Portsmouth or elsewhere. Because the Berwick economy relied more on the exchange of goods and labor than cash, the men working for Hamilton in all these different capacities would have been rewarded with West Indian rum, molasses, and other items from abroad. They might also have earned several day's use of Hamilton's saw mill, or perhaps a day's use of his gundalow to transport goods to Portsmouth. Nathan Lord indicated in his store accounts the variety of services exchanged between store-owner and customer. For example, it would not have been uncommon for someone to dig potatoes for two days in order to earn some ready cash.

Hamilton also probably employed someone to work in his Berwick store, to keep track of all these transactions. He might have even taken an apprentice, as Nathan Lord did for six years,(14) to teach him the "trade science and mystery" of a merchant. In addition to store workers, Hamilton needed people to work on his ships. Besides employing shipwrights to build his ships, Hamilton had to locate mariners for his voyages. Part of the crew of Hamilton's ships very likely came from Berwick. Nathan Lord, who captained one of Hamilton's ships as well as several of John Lord's, drew much of his crew from the area. Lists of the crew under Lord indicate men from Berwick, Portsmouth, and Somersworth.(15)

The existence of just a few prominent merchants in Berwick greatly affected the lives of some of the residents by providing a vibrant economic network. Benjamin Gerrish, a Berwick mariner, kept a diary in the year 1791, which well describes his relationship to the mercantile business.(16) Besides going to sea, Gerrish was often "imploid makeing boat sails." One day he "hir'd Mr Chace's Bote to Portsmth and Cary'd down 414 feet to Saml Hill for which I got 57 in Cash Goods & a due bill" (Samuel Hill was a Portsmouth merchant whose store was next door to Hamilton's.) Gerrish's diary indicates that he himself traveled quite often down the river to Kittery or Portsmouth. Far from being remote, Berwick was an easy journey to the bustling port of Portsmouth. Gerrish also attended the launching of one of Hamilton's ships, the brig OLIVEBRANCH - "went to Launching of Col Hambletons brig…" - and two weeks later wrote that "Col Hambletons Brigg set off for Portsmouth…." From Benjamin Gerrish's diary, we can see how a mercantile business such as Hamilton's was a mainstay of the Berwick community.

Jonathan Hamilton was not singular in being wealthy, prominent, and influential in Berwick society, yet the house he built with his fortunes around 1785 clearly stood out above all the other dwelling houses in the town. Tax records taken in Berwick, although they describe only monetary worth, give a good impression of the status of Hamilton's holdings as compared to other residents (see Appendix 4). In 1798, Hamilton's dwelling house alone was worth $3000, twice as much as the next highest valued house. In land valuations, Hamilton ranked only below John Haggens, owning a total of 398 acres, 8 perches [a perch = 30.25 square yards] valued at $3195. Although Hamilton owned all of this, over 100 acres of it was occupied by other men. Various deeds and tax records all indicate that Hamilton exerted influence in Berwick not only as a merchant but also as a landowner.

One last indication of Hamilton's

status in his community is the ship that was built in his

memory, 13 years after his death. Joshua Haven, Hamilton's

son-in-law, was living in Hamilton House in 1815 when he built

the 322 ton ship HAMILTON.(17) This Berwick-built ship may

even have been launched on Hamilton's property. The owners of

the vessel were Nathaniel A., John, & Joshua Haven, and

Henry & Alexander Ladd. It is interesting to note that the

Havens were then occupying half of Hamilton's Portsmouth store

(which had been divided at his death), while the Ladds owned the

other half. The HAMILTON was obviously a memento of the man of

whom they were reminded daily by their homes and stores, but it

was also a tribute to someone who had been an influential figure

during his lifetime.

Jonathan Hamilton as Merchant and Ship owner [Contents]

Part I: Domestic Interests

Though he was prominent and influential in Berwick, neither Hamilton's mercantile activities nor his community involvement were confined to that town. Hamilton the merchant was deeply involved in Portsmouth affairs, and centered his mercantile business in that bustling port. Yet Portsmouth and Berwick, economically dependent upon one another, were equally important in the success of Hamilton's mercantile endeavors. The title of merchant perhaps best describes Jonathan Hamilton. As a merchant, Hamilton made his fortune, achieved recognition in Portsmouth and Berwick, and had dealings with a large sector of both these communities. It is not certain when exactly Hamilton began acquiring and exchanging goods, but it might have been as early as the 1760s. By 1774, when Hamilton's title in deeds appears as "gentleman" rather than "yeoman," he had established himself as a trader. As a young man he built his business "by the retail trade, which mainly consisted in selling salt-fish, molasses, rum, sugar, and tea to the farmers in exchange for wood, timber, poultry, butter, and eggs.(18) Hamilton probably began accounts with Portsmouth merchants at this time, providing them with the goods from up the river while providing the farmers with items from abroad. As account books show, this economy was based on exchange of goods and labor more than cash, but Hamilton would have taken an occasional cash profit.

Hamilton's business became progressively more complex, as he rose from being a simple trader to working from a warehouse, to operating a store, to owning his own ships.(19) In 1778, Hamilton purchased from Elizabeth Wingate for 150 pounds a lot on merchants' row in Portsmouth extending to the water with a warehouse standing on it. This lot and warehouse, "containing all the Land & Water privilege of sight of wharfing into said River"(20) stood on Fore Street (now Market Street) between the wharves of Samuel Cutts and Samuel Hill. With his wharfage on the water, Hamilton would have been able to bring his goods down the river, unload them at his wharf, and store them in his own warehouse. Hamilton's warehouse and wharf, in the busiest section of a large port, provided a pivotal spot for his business. The wharf provided easy access for his ships coming into port, and his warehouse afforded him more flexibility in the acquiring and selling of goods.

By 1785, approximately the time he began the building of his mansion, Jonathan Hamilton started having his own ships built, which he continued to do until 1801. In the 1785 he had two vessels built, both of which he owned with Samuel Rice. The schooner DOVE, 64 tons, was built in Kittery, while the brig POLLY, 179 tons was built in Berwick. The first voyages of these vessels, in 1786, were to the West Indies. Samuel Rice was the master on the POLLY, and _____ Trefethen mastered the DOVE.(21) Surprisingly, there is no evidence of Hamilton ever being a master on a ship. Unlike some other successful merchants such as John Langdon, who began his merchant career sailing another's ship,(22) Hamilton's career appears to be confined entirely to the land. Although he may not have taken voyages on his own ships, several letters show that he was closely involved in setting the itinerary and offering advice from home port.

Until the year of his death, Jonathan Hamilton continued to have vessels built in Berwick. Hamilton appears to have been one of the few ship owners in Berwick, and over half of the tonnage produced in Berwick during the 1780s and 1790s was made up of Hamilton's trading ships. In 1785, the Massachusetts Tax Valuations indicate that the town of Berwick had a total of 338 tons of "vessels & small craft."(23) Hamilton himself owned at least 243 tons of vessels in that year, comprising nearly two-thirds of Berwick's total tonnage. Who Hamilton's shipbuilder(s) was remains unclear. The masterbuilder of his last ship, TWO SISTERS, built in Berwick in 1800, was Samuel Cottle.(24) It is uncertain whether Cottle built additional vessels for Hamilton, or whether he was hired for just this one ship. Considering the small number of vessels produced in Berwick each year (usually about one), it seems doubtful that Berwick had its own fulltime shipwright. The Customs House Records and Portsmouth Directory give a good idea of the number of vessels produced in Berwick from 1783 to 1839. In any one year there were never any more than four vessels built (four vessels came from Berwick in the year 1800), and many years no ships were produced. From 1820 to 1823, and 1826 to 1831, no vessels came down the river from Berwick. During the years when Hamilton was having ships built, however, an average of 1.5 ships were built in Berwick each year.

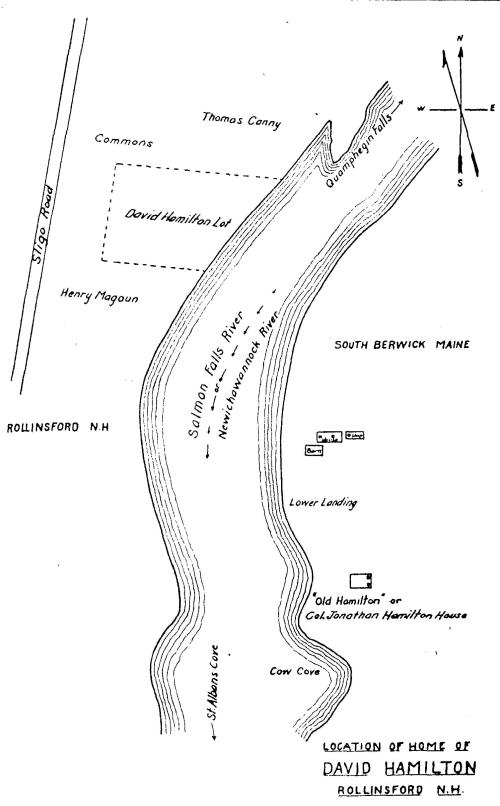

The shipyard in Berwick undoubtedly lay on the Salmon Falls River, this being the only waterway wide and deep enough to accommodate the launching of ships, and there is some evidence that Hamilton may even have had a shipyard on his own property. David Moore, the previous owner of the Hamilton property, was himself a wealthy and prominent merchant. The inventory of his estate, taken in 1777 after his death included"…the Wharf and the Ways for Building of Vessels, and the Beech for Graving…"(25) This part of Moore's estate went to the administrator William Rogers, and Hamilton purchased it from Rogers in 1790. Along with a dwelling house, outhouses, and barns, Rogers deeded to Hamilton "…1/3 part of wharf & warehouse also 1/3 part of beach & ways for graveing and building vessels…"(26) This information tells us not only that vessels were built on the property, but also that they returned there after being out at sea. Graving vessels, or cleaning the bottom of a ship and covering it with pitch, was a form of maintenance that was probably done yearly. The fact that this was done in Berwick rather than in Portsmouth provides evidence that Hamilton's ships did come back up the river after journeys at sea, and may indeed have tied up at the wharves outside the Hamilton House, as legend tells us (see appendix 2).

All of the wharves at Hamilton's house may also have been in place from David Moore's time. As Hamilton did later, Moore ran his mercantile business from his property, and had a wharf and warehouse on the river. From his father's estate, Moore inherited "2/3 parts of the wharfe with the Easterly Ware-house commonly called the New Ware House standing on said wharfe…"(27) In the 1771 Tax Valuations, David Moore is listed as having 266 feet of wharf on his property. When Hamilton purchased this land in 1783 it included Moore's wharves, and unless he built new additional wharfage, we can assume that Hamilton owned about 266 feet of wharf space on the river, just west of the house.

Jonathan Hamilton was not only equipped with a place to build ships by 1790, he also had the necessary supply of timber required for their construction and a way of preparing it. In February 1785, Jonathan Hamilton and Humphrey Chadbourn purchased from William Roger "… the whole of my Saw Mill Standing on the Northerly Side of the River on the Falls called the Great Works in said Berwick together with all the Iron Works thereto belonging or in any wise appertaining as it now stands Together with two thirds parts of the land priviledge water coarses Falls Brow & c. in or belonging to said priviledge."(28) It is interesting that Hamilton purchased this mill in 1785, the year he began building vessels as well as about the time he would have begun building his three-storey Georgian mansion. Constructed primarily with wood, the house necessitated huge amounts of timber prepared at a saw mill. Hamilton and Chadbourn's mill was located just about a quarter of a mile up the river, at a convenient location for transporting timber or iron to the property. With these goods available, and his own yard for building vessels, Hamilton would only have needed to hire a builder for his ships. It is possible that he could have brought Portsmouth builders or other outsiders to his property to have these vessels made.

Although I have ascertained that Hamilton's ships did return up the river, they would not have been able to drop anchor and stay for any length of time. Because of the tides, the river in front of Hamilton House would get too shallow to allow large vessels to remain afloat; therefore, Hamilton needed to find wharfage in Portsmouth. His own wharf, extending from Fore Street, was only 35 feet in length, as was his storefront.(29) This would not have allowed Hamilton to dock more than one ship at a time, and he apparently chose to keep his vessels elsewhere after they had unloaded. Thomas Sheafe ran a large wharf and warehouses next to the Portsmouth Pier, near the foot of State Street, and his wharf book indicates that Hamilton often rented wharf space from him. Hamilton would leave his ships there for anywhere from three to forty days, and in at least one case brought his ship up the river "to grave" for four days while wharing at Sheafe's.(30) Hamilton also rented wharfage from John Langdon,(31) and probably from other Portsmouth merchants as well.

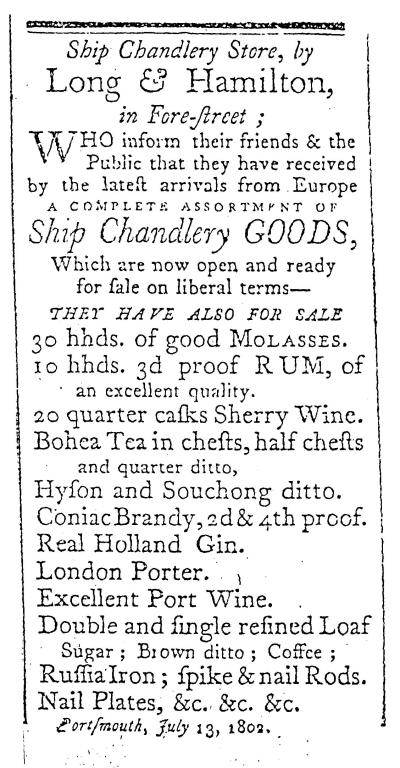

Although he might have wanted to rent

wharfage space to make efficient use of his property, Hamilton

was essentially a self-sufficient merchant. Besides owning his

own ships, he ran two stores, one on his property in Berwick and

another on Fore Street in Portsmouth. Very little is known about

the operations of his Berwick store, as all the information on

it derives solely from the inventory taken after his death. This

store contained large quantities of tea, sugar, coffee,

molasses, rum, as well as some timber

and tools possibly used for building ships.(32)

It was probably used as more of a storehouse than an actual

place of business. Hamilton's store in Portsmouth, "Long &

Hamilton"(33) was in business by

1800, and was operated as an actual retail store. Hamilton built

his store on Fore Street much earlier than 1800, but it is not

clear what function it served before that time. Unlike the

Berwick store, "Long & Hamilton" was a ship chandlery store,

specializing in all kinds of goods relevant to building and

sailing vessels. An advertisement which appeared in the New

Hampshire Gazette in March 1801 (see appendix 10) gives us

a clear idea of what articles were for sale at the store. Yet

"Long & Hamilton" was hardly restricted to ship-related

items. It appears from additional advertisements, as well as the

store inventory, that Hamilton sold anything that his ships

brought back from their travels, especially molasses, rum, wine,

tea, and other liquors (see appendix 9). The store was destroyed

by the fire of 1802, just three months after Hamilton's death.

An inventory, totaling over $3000 worth of goods was taken just

before the fire, yet the division was not settled until after

the fire had done its damage. It is unclear whether the store

actually burned to the ground, but judging from the fact that

the store was subsequently divided between John and Oliver

Hamilton, it is likely that the store was not completely

destroyed.

Part II: Voyages Abroad [Contents]

Though there is evidence of Jonathan Hamilton's mercantile activities in Berwick and Portsmouth, it is really in the activity of his fleet that we see his business fully functioning. No evidence points to Hamilton himself ever traveling beyond the borders of this country, yet he had numerous business concerns abroad and was obviously deeply involved with them. The success of Hamilton's business at home depended on the steady export and import of goods by Hamilton's fleet of trading vessels. The most frequent destination of Hamilton's ships was the West Indies, but they also touched all points of the globe (see appendix 6). The POLLY ventured to the Orient in 1789, and the TWO SISTERS went as far as St. Petersburg, Russia on a voyage in 1801. Hamilton's vessels also visited many European countries, Newfoundland, and South America. These destinations were quite typical of Portsmouth merchants' trading ships, especially the West Indian ports.

Nathan Lord's papers tell us quite a bit about what a voyage on one of Hamilton's ships might have been like. The BETSY usually carried a crew of about eight men: 1 master, 1 mate, 4 or 5 seamen, a cook, and maybe an apprentice. One list of the crew on a 1790 voyage to Tobago includes two "green hands", whose function is uncertain. Some masters sailed many voyages for Hamilton, indicating that they would have developed a working relationship with Hamilton. The other members of the crew, however, may have received their orders and pay from the master rather than the ship owner. The master (Nathan Lord) earned 3 pounds per month, the mate 2 pounds, 14 shillings, and the seamen 2 pounds, 2 shillings each. The total time of service for a West Indian voyage was about 4 1/2 months, which would make a master's entire pay 13 pounds, 18 shillings. An agreement was signed between Hamilton and the crew for a particular voyage to Tobago, specifying the terms of hire:

An agreement between the owner on the one part, & the Captain Officers and Seamen on the other part of the Brigantine Betsey bound on a Voyage to the West Indies and Back to Portsmouth in New Hampshire - In consideration of the same as Monthly Wages to each of our names affixed at the signing hereof We the said Captain Officers and Seamen do agree to perform the Voyage above specified - We the said seamen do hereby promise to Obey the said Captain & other Officers of said Brigantine Betsey and faithfully do & perform the duty of seamen as required by them and that we will not upon any accounts go on shore or be absent from duty without first obtaining Liberty from the captan or the Commanding Officer on board --. And in Case of Disobedience to the Captain or any other officers of said Brigantine, neglect of Duty, Pillage Embezzlement, Desertion or Mutiny, the seamen so offending shall forfeit, all his Wages adventure & all his or then others things on Board. We the said Captain Officers & Seamen do hereby acknowledge that we have received the advance wages as set against our names --(35)

These crew lists also give us an idea of the danger involved in sailing one of these ships. Beside each name, after the wages, are three locations to indicate when the man left the ship. The first is "Dead," the second "Discharged," and the last "Deserted." Luckily, all the crew members on this voyage survived to return to port.

The fate of many of Hamilton's ships also attests to the danger of their passages. Of Hamilton's twelve ships, two were lost at sea, and three were captured by enemy ships and never returned. One captured ship did finally make it back to home port. In 1799 the ship CATO under Captain John Parker was captured by a French privateer of 14 guns and 75 men. A letter to Jonathan Hamilton from the Captain describes this experience: "They came under the lee quarter and jumped on board like so many pirates, broke open my chest and trunk, took all my papers and cloathes from me not leaving me a shoe to my foot, then threw me head foremost down the gangway and told me she was a fine prize. For five days we lived upon six ounces of mouldy bread and a little raw beef…"(36) Luckily, a British ship recaptured the CATO, freed the prisoners, and later returned the ship to its rightful owners.

The brig OLIVEBRANCH was not as fortunate as the CATO. On her return voyage from Lisbon in 1792, the OLIVEBRANCH under William Furnass was captured by Algerian pirates. The letter Furnass wrote to Hamilton while being held prisoner was published in the New Hampshire Gazette on March 15, 1794. Furnass describes the sufferings of the ten American prisoners: "The labour is very hard, and they give us nothing but bread and water, and so little of that, that it is hardly sufficient to sustain life; and unless our humane Congress gives us some small allowance to alleviate our sufferings, we must continue in the most abject slavery…. We were stripped of every thing when taken but life, and it is almost enough to take that, to destitute of every thing but horror…(37) Finally in July 1796, the prisoners were redeemed by the Americans, and, after being quarantined in Marseilles, returned home.(38)

The dangers of overseas voyages may

have been one of the reasons that Jonathan Hamilton chose to

remain on land, but despite the physical distance from his

ships, Hamilton appears to have kept in close contact with his

masters while they were on voyages. Hamilton sent Nathan Lord in

Tobago two very similar letters, written one day apart, in

December 1790.(39) Hamilton's

attempt to overcome the uncertainties of mail delivery might

explain the duplication. Although these letters are written in a

rather sloppy hand with poor and inconsistent spelling (compared

with other manuscripts of the same time), they reveal Hamilton's

experience and wisdom in mercantile matters. Hamilton advises

Lord to shorten his stay in Tobago, so that he can leave before

all the other ships and get high prices for the goods he brings

back to Portsmouth. Hamilton updates him on the current prices

for sugar and rum, but adds that "much depend on your being in

Verey arley." In case of "Bad Wither," Hamilton also gives Lord

permission to stop in Baltimore and sell some goods if they will

go for more than they would in Portsmouth. Hamilton signs each

letter modestly: "I am sir your friend and humble servant -

Jona. Hamilton." Judging from these letters, Hamilton had good,

steady relations with his masters while they were making voyages

for him. It is easier to comprehend, after reading his

correspondence, how Hamilton achieved such success in the

mercantile business.

Jonathan Hamilton as the

Well-Connected Portsmouth

Businessman

[Contents]

Although Hamilton did not begin operating his store in Portsmouth until the 1790s, his introduction into the Portsmouth community occurred much earlier. On June 23, 1772, Joshua Wentworth proposed at a meeting of the St. John's Lodge of Freemasons that Jonathan Hamilton become a member.(40) That same night he was given the first two degrees in Masonry, and the following year was raised to the degree of Master Mason. The evidence of Hamilton's membership in St. John's Lodge shed new light on Hamilton's position in the Portsmouth community. Not only did Hamilton become a member at the young age of 27, but his sponsor, Joshua Wentworth, was one of Portsmouth's best known businessmen. Colonel Wentworth was later elected to the Continental Congress, served as a State Senator, and sat on the Governor's Council.(41) It is uncertain how Hamilton made this important Portsmouth contact, but it undoubtedly affected his status in that community.

Freemasonry may have been the network that led to a business partnership. The Long of Hamilton's ship chandlery store "Long & Hamilton" has remained a question (see note 33), but one possibility is that Hamilton met Pierse Long or Edward Long, both masons, through his involvement in the St. John's Lodge. Hamilton, coming from a much smaller inland community, would have needed the guidance of a more experienced merchant, such as Pierse or Edward Long. Woodbury Langdon, from whom Hamilton later purchased the land for his mansion, was also a mason and possibly a personal friend of Hamilton.

Jonathan Hamilton made many other Portsmouth connections during these early years. The co-owner of Hamilton's first two vessels, the DOVE and the POLLY, was Samuel Rice, a Portsmouth man.(42) Rice and Hamilton were involved in several different ways. They not only owned these two ships together, but Rice served as master on the first eight voyages of the POLLY, as well as on the first voyage of Hamilton's JOSEPH. In addition, Rice commanded Hamilton's Privateer FANCY on a cruise in 1781. (43) Samuel Rice even had a store on Fore Street, as Jonathan Hamilton did.(44)

Since most of the important figures in Portsmouth were merchants, Hamilton made connections in Portsmouth through his own business. Between 1781 and 1792, Hamilton kept extensive accounts with John Langdon. (45) Hamilton supplied Langdon with lumber, masts, spars, and planks from up the river, and Hamilton received cash, merchandise, and wharfage in return. Hamilton also kept an account with merchant James Rundlet during the 1790s. (46) In 1791, when Rundlet was just starting out, he sent a shipment of salmon and beef on board Hamilton's schooner DOVE to sell in the West Indies.(47) In 1795, Rundlet lists in his commission sales book fifty boxes of Lisbon lemons bought from Jonathan Hamilton, which he sells gradually and makes a $24 profit. Hamilton probably had relations like these with many merchants. As Portsmouth account books reveal, local merchants networked to maximize their profits, rather than attempting to work completely independently. Although Hamilton had the means to operate a self-sufficient business, he chose to engage in this interdependent network of mercantile exchange.

Hamilton operated his privateers with the help of other men, most likely out of Portsmouth. Between 1775 and 1782, many Portsmouth merchants, their business hindered by the dangers of war-time trade, took to privateering. Although privateering ventures were extremely dangerous, some of the more brave believed the possibility of a capture outweighed these dangers. Privateering vessels were officially commissioned by the Continental Congress, yet the owner was free to do what he liked with his captured enemy vessels. Unlike more established merchants, Hamilton owned no trading vessels at the time of the Revolution and must have purchased his first ships expressly for privateering. His first privateer, the FANCY, he co-owned the Robert Stevenson of Kittery. Samuel Coffin of Newburyport commanded the first cruise in 1780, while Samuel Rice commanded the second cruise in 1781. On each of these cruises, there were 25 crew men. Hamilton probably gathered much of his crew from Portsmouth, where he would have found plenty of willing mariners. Another of Hamilton's privateers, the NEPTUNE, made a cruise in 1781 with a smaller crew of 12.

There is no evidence of Hamilton succeeding in these ventures, but judging from his early accumulation of wealth, he certainly could not have failed miserably. Had Hamilton made any captures, the prize would have been divided between himself and his crew by a prearranged system of shares, with him getting at least half.(48) Many successful privateers would advertise their prize in the New Hampshire Gazette and sell it at public auction. In 1781, George Wentworth advertised for sale at public vendue on his wharf the "prize Brig Adventure, together with all her Sails, Rigging, Cables, Anchors, & c. as she came from sea.… The Ship Diana, and all her Appurtenances. Likewise, all her War-like stores, consisting of Four Pair Four Pound Cannon, Powder, Shot, & c. & c."(49) Because the booties were distributed to the public through these kind of acutions, the life of Portsmouth would have been colored by the various failures and successes of privateersmen.

Aside from business associations with

Portsmouth merchants, Hamilton undoubtedly developed personal

friendships with these men. It is interesting to note that two

of Hamilton's daughters married men with whom Hamilton had a

working relationship. His daughter Olive married Joshua Haven, a

Portsmouth merchant, while his eldest daughter Mary married John

Parker, a former master on Hamilton's CATO. These men may have

paid visits to Col. Hamilton at his Berwick mansion, and gotten

to know the Hamilton family. Sarah Orne Jewett tells of the

grand entertaining that went on at Hamilton House. She describes

"the fine ladies and gentlemen, and the great dinner-parties,

and the guests who use to come up the river from Portsmouth, and

go home late in the moonlight evening at the turn of the tide."(50) The Hamilton House, so

different in situation and grandeur from the city-built

Portsmouth mansions, was probably widely known among Portsmouth

merchants. Many of the men that Hamilton did business with

during the day may have visited at Hamilton House evenings, to

be entertained by Jonathan Hamilton and his wife Mary in the

grand parlor.

Epilogue: The Downfall of the Hamilton Family [Contents]

The history of Jonathan Hamilton turns immediately from a success story to a tragedy following his death in September 1802. Hamilton died young and unexpectedly, without leaving any provisions for the division of his estate. Hamilton had lived in his mansion a mere fourteen years, and his business was at its height; obviously, he was not thinking about death in 1802. He ended his career by importing in one year 2800 gallons of molasses, 6900 pounds of sugar, 5500 gallons of rum, 18,000 pounds of coffee, 7400 bushels of salt, 11,500 gallons of wine and large quantities of sailcloth. (51) He still owned six vessels: the JOSEPH, complete with its cargo of coffee, rum, brown sugar, and molasses from Demerara; remnants of the MARY which had been lost at sea; the CATO sitting at Norfolk after being recovered from its capture, and the OLIVE, POLLY, and GEORGE. "Long & Hamilton" was doing a booming business, as an advertisement in the Gazette two months before Hamilton's death indicates (see appendix 9).

After his death, appraisers took an inventory of the contents of Hamilton's house and store, and divisions were made among the children. John, the eldest son, received the mansion and half of the Portsmouth store, while Oliver received some lands and the other half of the store. Olive Haven, Mary, Joseph, and George all inherited large sums of money from the estate. Jonathan Hamilton's mansion and Portsmouth store were valued at $6000 each, minus contents.

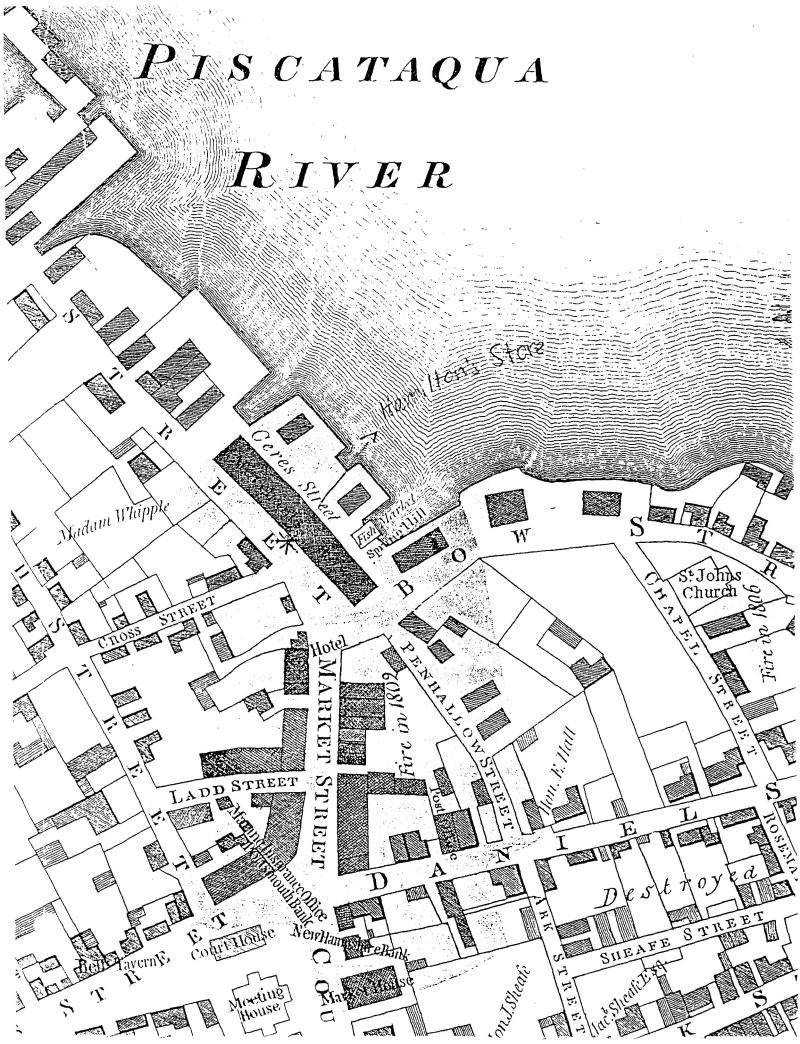

The next tragedy occurred in December 1802, when a fired raged through Portsmouth, destroying many buildings in the center of town including Hamilton's store (see appendices 7 and 8).(52) The extent of the damage is uncertain, but since the store and wharves were still divided in half between John and Oliver Hamilton, we can assume that something remained.

All four of Jonathan Hamilton's sons attempted to follow in their father's path, yet there is no evidence that they were very successful in the short time they were active. John Hamilton, the eldest son, acquired his father's brigs POLLY and OLIVE and sent them on voyages to Grenada, Copenhagen, Demerara, and Tobago. He also had the brig JOHN ADAMS built in 1800 in Durham, and co-owned it with Edward Long. Yet John Hamilton, like his father, died an untimely death. He died in November 1805 at the age of 28 of "paralytic consumption."(53) The mansion house and John's share of the Portsmouth store went to Oliver Hamilton, who had sold them all before the time of his death.

Oliver, the second eldest son, also tried his hand at the mercantile business, but he was unsuccessful and maybe unpopular as well. He took more than three years to settle the estate of his brother, while creditors became quite impatient. Oliver was finally asked to appear in court in 1809, and eventually did complete the settlement.(54) When Oliver died in 1813, no one appeared to administer his estate, and someone had to be appointed several years later. Considering he still had sisters and other relatives in the area, it is odd that no one came forward after his death to settle his affairs.

Oliver, George, and the youngest son Joseph all lived and worked in Portsmouth as merchants. Tax lists for the city of Portsmouth trace the downfall of their businesses, especially Oliver's. Between 1807 and 1812, the taxes on his property were lower each year: 1807: $61.30, 1808: $49.30, 1809: $45.00, 1810: $54.50, 1811: $37.50, 1812: $3.30.(55) Whether the embargoes of 1812 destroyed his business, or whether it was Oliver's own mismanagement, we cannot be certain. Oliver was forced to take a mortgage out on his part of the store in 1808, even though he had sold John's share of the store the previous year. He finally sold the store to Nathaniel A. and John Haven in 1811.(56) Joseph and George Hamilton both died in 1812, and Oliver died a year later, in 1813.(57) The cause of these deaths is unknown.

After 1813, no male descendents of Jonathan Hamilton remained to carry on the name (see appendix 1). John Hamilton, who had died earlier, married Mary Eastham (possibly from Exeter) in 1796, but there is no record of any children.(58) All of Hamilton's daughters eventually married: Betsey married Peter Clark in 1792, Olive married Joshua Haven in 1802, Mary married John Parker in 1804, and Polly married Emery Goodwin, probably before her father's death. Olive and Joshua Haven, who lived in the Hamilton House from 1811 to 1815, had four small children living there with them. Appropriately, the eldest two were named Jonathan Hamilton Haven and Mary Hamilton Haven.(59)

A decade after Jonathan Hamilton's

death, very little remained to remind others of his once

powerful influence in both Berwick and Portsmouth, save the

gracious mansion which still stands today. Although it has seen

many owners and changed its appearance several times, the house

still bespeaks Hamilton. Today it stands as a monument to the

success of a self-made man, one who rose from humble origins to

become one of the most important members of his community.

Bibliography [Contents]

I. Manuscripts

Benjamin Gerrish Diary, 1791.

Maine Historical Society, Portland, ME.

Elizabeth Goodwin Papers, Dartmouth

College Library, Hanover. NH.

John Langdon Papers, New Hampshire

Historical Society, Concord, NH.

Nathan Lord Account Books, 1796-1798.

Old Berwick Historical Society, South Berwick, ME.

Nathan Lord Papers, Baker Library,

Harvard School of Business Administration.

James Rundlet Papers, SPNEA archives,

Boston, MA.

Thomas Sheafe Papers, Baker Library,

Harvard School of Business Administration.

II. Biographies and Genealogies

Hamilton, Samuel King. The

Hamiltons of Waterborough. N.p., 1912.

Hammond, Otis G., ed. Letters and

Papers of Major-General John Sullivan. 3 vols. Concord,

NH: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1930.

Keyes, Dot. "Genealogy of the Hamiltons

of Berwick, Maine." Article excerpted from York County

Genealogical Society Quarterly Journal.

Mayo, Lawrence Shaw. John Langdon

of New Hampshire. Concord, NH: Rumford Press, 1937.

Stackpole, Everett S. Old Kittery

and Her Families. Lewiston, ME: Press of Lewiston Journal

Co., 1903.

III. Newspapers and Magazines

A. Newspapers

The New Hampshire Gazette

The Oracle of the Day

B. Magazine Articles

Hawthorne, Hildegarde. "A Garden of

Romance, Mrs. Tyson's, at Hamilton House, South Berwick, Maine."

Century 80 (1910): 778-786.

Hennessy, William G. "The House of

Hamilton." Shoreliner 3 (July, 1952) 9-16.

Kingsbury, Edith. "Hamilton House:

Historic Landmark in South Berwick, Maine." House Beautiful

65 (1929): 782-787, 874, 876.

Rand, Edwin Holmes. "Maine Privateers

in the Revolution." The New England Quarterly (Dec.

1938): 826-834.

Shelton, Louise. "The Garden at

Hamilton House." American Homes & Gardens 6 (1909):

422-425.

IV. Histories, etc.

Adams, John P. Drowned

Valley: The Piscataqua River Basin. Hanover, NH:

University Press of New England, 1976.

Allen, Gardner Weld. Massachusetts

Privateers of the Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP,

1927.

Bell, Charles H. History of the

Town of Exeter New Hampshire. Boston: J. E. Farwell &

Co., 1888.

Caldwell, Bill. Rivers of Fortune:

Where Maine Tides and Money Flowed. Portland, ME: Guy

Gannett Publishing Co., 1983.

Carroll, Gladys Hasty. Dunnybrook.

New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1978.

Foss, Gerald D. Three Centuries of

Freemasonry in New Hampshire. Somersworth, NH: The New

Hampshire Publishing Co., 1972.

Gundersen, Mary Ann. Seclusion and

Connection: Changes in the Economic Embeddedness of Berwick,

Maine 1630-1820. N.p., 1986. (Master's Thesis, UNH).

History of York County, Maine.

Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1880.

Howells, John Mead. The

Architectural Heritage of the Piscataqua. New York:

Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1937.

Hutchins, John G. B. The American

Maritime Industries and Public Policy, 1789-1914.

Cambridge MA: Harvard UP, 1941.

Jewett, Sarah Orne. Country By-Ways.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1881.

---. The Old Town of Berwick.

South Berwick, ME: Old Berwick Historical Society, 1967.

---. The Tory Lover. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1901.

Laing, Alexander. Seafaring America.

New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1974.

A Memorial of the One Hundredth

Anniversary of the Founding of Berwick Academy South Berwick,

Maine. Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1891.

Nelson, George A. Early U. S.

Customs Records and History, Portsmouth, NH 5 vols.

Portsmouth: Portsmouth Athenaeum, 1979.

Quilici, Ronald H. A Voyage to Antiqua: A Social and

Economic Study of the Maritime Activities of Colonial

Portsmouth, New Hampshire. N.p., 1973 (UNH Master's

Thesis).

Ricker, Jennie de R. South Berwick:

Pages from the Past. N.p., n.d.

Robinson, John and Dow, George Francis.

The Sailing Ships of New England 1607-1907. Westminster,

MD: J. William Ekenrode, 1953.

Saltonstall, William G. Ports of

Piscataqua. New York: Russell & Russell, 1941.

Spencer, Wilbur D. Pioneers on

Maine Rivers. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co.,

1973.

Stilgoe, John R. Common Landscape

of America,1580 to 1845. New Haven: Yale UP, 1982.

The Story of Berwick.

Somersworth, NH: New Hampshire Publishing Co., 1963.

Willis, John Lemuel Murray. Old

Eliot. 2 vols. Somersworth, NH: New England History Press,

1985.

Winslow, Richard E. The Piscataqua

Gundalow: Workhorse for a Tidal Basin Empire. Portsmouth:

Portsmouth Marine Society, 1983.

V. Government Records, Church Records, etc.

A. Government Records

Department of Commerce and Labor,

Bureau of the Census. Heads of Families at the First Census

of the U. S. Taken in the Year 1790. Washington:

Government Printing Office, 1908.

Direct Tax Census of 1798. York County.

New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston.

Portsmouth Tax Lists, Portsmouth City

Hall.

Pruitt, Bettye Hobbs, ed. The

Massachusetts Tax Valuation List of 1771. Boston: G. K.

Hall & Co., 1978.

United States Tax Valuations of 1816,

York County. York County Court House, Registry of Deeds, Alfred,

Maine.

Valuations for the Town of Berwick,

1781-1785. Massachusetts Archives, Boston.

B. Church Records

Rainey, Louise H., ed. Records of

the North Church, Portsmouth, NH, 1779-1835. N.p., n.d.

Records of St. John's Church, Portsmouth,

NH, 1795-1884. N.p., n.d.

Wells, Theodore, ed. The Records of

the Church of Christ at Barwick. N.p., n.d.

C. Miscellaneous

Portsmouth City Directory, 1839.

Registry of Deeds and Registry of

Probate, Rockingham County Court House, Exeter, New Hampshire.

Registry of Deeds and Registry of

Probate, York County Court House, Alfred, Maine.

Secretary of the Commonwealth. Massachusetts

Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. Boston:

Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1900.

Spencer, Wilbur D. A List of

Revolutionary Soldiers of Berwick. N.p., 1898.

Stemmons, John D., ed. The United

States Census Compendium. Logan, Utah: The Everton

Publishers, 1973.

Appendix 1 [Contents]

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Soloman b. 1666 Jonathan b. 1672 |

m. Mary Hearl c. 1720 m. Abigail Hodsdon 1721 |

Abiel; b. 1680 James? |

|

|

||

|

Jeremiah bpt. 1725 Jonas bpt. 1731 |

m. Elizabeth

|

Susanna bpt. June 21, 1739 m. Edmund Haggens in 1788? Abigail b. June 25, 1738 |

|

|

||

|

Sarah bpt. 1744 Deborah bpt. 1744 |

bpt. 1745-6 - d. 1802 m. Mary Manning 1771 m. Charlotte Swett 1800 |

|

|

|

||

|

Mary c. 1775 m. John R. Parker John 1777-1805 Betsey c. 1776 m. Peter Clarke 1796 |

m. Joshua Haven 1802 |

George 1785-1812 Joseph 1789-1813

|

|

|

||

|

|

Olive b. 1811 |

|

*This genealogy lists Bial and Abigail as Jonathan's

grandparents, but this turns out not to be clear. Two of David

Hamilton's sons were Bial (b. 1676) and Abiel or sometimes Abel

(b. 1680). Everett Stackpole in Old Kittery and her Families

(1903) is a main authority on this topic; he says that Bial

Hamilton married first Mary Hearl sometime before 1715 and then

later married Abigail Hodsdon (daughter of Joseph Hodsdon and

Margaret Goodwin) in 1721. By this second marriage, he

became the father of Joseph Hamilton who was Jonathan's father.

However, the

town records of Berwick at the Berwick Town Hall, near the end

of volume 1, list the marriage of Abial Hambleton and Abigail

Hodsdon on December 26, 1721; here also are listed the births of

two children to Bial and Mary Hambleton: Keziah on 30 March,

1715, and Solomon on 6 June, 1716. (Stackpole also

indicates that Abiel was first married in 1705, to Deborah, and

that there is evidence they had some children.)

So, it seems

uncertain whether it was Bial or Abiel whose second wife was

Abigail and who became Jonathan's grandfather, since it seems

agreed that Abigail was Jonathan's grandmother. (Terry Heller)

Appendix 2 [Contents]

Woodbury Illustration of Hamilton

House from The Tory Lover,

Showing Ship at Wharf

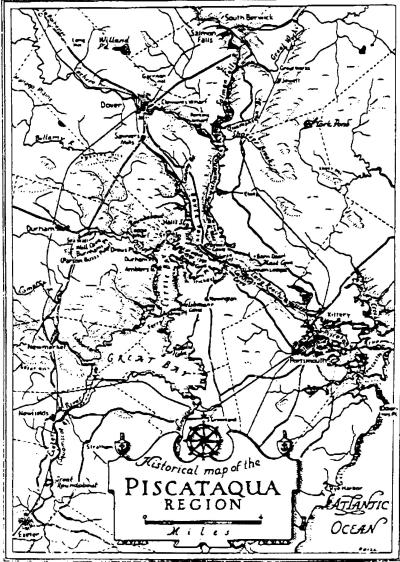

Appendix 3 [Contents]

Map of the Piscataqua Region,

Showing Riverways between South Berwick and Portsmouth

Appendix 4 [Contents]

1771, 1798, and 1816 Tax Valuations of Berwick

Comparing values of Hamilton estate with highest valued properties

The names in boldface indicate who was living on the Hamilton property at the time of the valuation. David Moore lived on the property in a mansion which burned sometime between 1777 and 1783; Nathan Folsom occupied the actual Hamilton House.

1771 Tax Valuation Lists:

Benjamin Chadbourn 94 pounds

Peter Morrell 64 pounds

Tilley Higgens 43 pounds

William Hight 42 pounds

David Moore 40 pounds

Ichabod Goodwin 35 pounds

John Hill 30 pounds

………………….

(Jonathan Hamilton 9 pounds)

| 1798 Direct Tax Census,

dwellings: Jonathan Hamilton $3000 John Cushing $1500 John Haggens $1500 John Lord $1500 Benjamin Chadbourn $1460 Ivory Hovey $1400 Dudley Hubbard $1380 |

1798 Direct Tax Census,

lands: John Haggens $4760 Jonathan Hamilton $3195 John Cushing $3155 Edmund Haggens $2432 Benjamin Chadbourn $2000 Ichabod Goodwin $1370 Ivory Hovey $1355 |

1816 Tax Valuations:

Doct. Ivory

Hovey $6842

Edmund Haggens

Esq. $6341

Ichabod Goodwin

$6166

Humphrey

Chadbourn $6028

Nathan B.

Folsom $5490

William A. Hayes

Esq. $4988

John Haggens

Esq. $4356

Appendix 5 [Contents]

Privateers:

Ship FANCY

1780-?

Brigantine

NEPTUNE 1781-?

Trading Vessels

| Name: | Tonnage: | Where Built: | Dates: |

| Schooner DOVE (owned with Samuel Rice) | 64 | Kittery | 1785-1794 |

| Brig POLLY (owned with Samuel Rice) | 179 | Berwick | 1785-1802 |

| Brig BETSY | 164 | Berwick | 1789-1794 |

| Ship CATO | 275 | Berwick | 1790-1803 |

| Brig OLIVEBRANCH | 110 | Berwick | 1791-1800 |

| Brig JOSEPH | 190 | Berwick | 1794-1809 |

| Ship GEORGE | 216 | Berwick | 1794 |

| Ship GEORGE | 232 | ? | 1795-1803 |

| Ship MARY | 107 | Berwick | 1795-1803 |

| Ship PROVIDENCE | 141 | ? | 1797 |

| Ship TWO SISTERS | 235 | Berwick | 1801-1802 |

Appendix 6 [Contents]

Destinations of Jonathan

Hamilton's ships and frequency of visits according to

Portsmouth Custom Records:

| Demerara, S.

America 25 West Indies 16 Martinque 10 Cadiz, Spain 4 Lisbon, Portugal 4 Liverpool, England 4 St. Thomas, W.I. 4 Tobago, W.I. 4 England 3 Grenada, W.I. 3 St. Ubes, W.I. 3 St. Martins, W. I. 3 Hamburg, Germany 2 Trinidad, W.I. 2 |

Bonavista,

Newfoundland 1 Boston, MA 1 Bristol, England 1 Dominica, W.I. 1 Figuera, Spain 1 L'Orient 1 Madeira 1 Nevis, W.I. 1 St. Eustatia, W.I. 1 St. Kitts, W.I. 1 St. Lucia, W.I. 1 St. Petersburg, Russia 1 Turks Island, W.I. 1 |

*The records are as they appear in the

Customs House Records; sometimes they specify the exact port,

and other times only a country or region is indicated.

Appendix 7 [Contents]

Map of Portsmouth, 1813, Showing

Section Destroyed by 1802 Fire

The first section below is the western portion, the second

section is the eastern portion of this map.