Main Contents & Search

Uncollected Stories

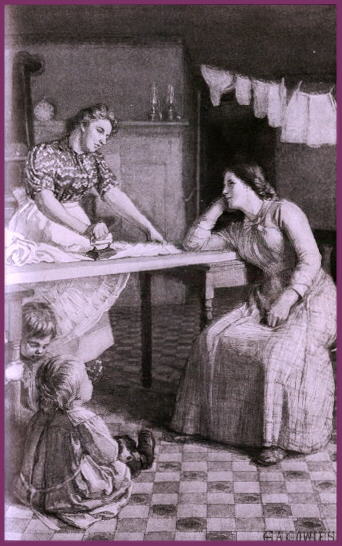

ELLENEEN

There was a cheerful noise within the house that mid-winter day, but Mary Ann Dunn looked up innocently from her ironing as her pretty younger sister opened the door and came in. Ellen had only arrived from Ireland in the late autumn; she was still a greenhorn, in spite of the first snow, and several weeks' steady work in the cotton mills of the next town, and even in spite of a fine American hat which waved its feathers in a sort of angry incoherence.

Mary Ann's two babies were playing with a puppy, and the three young creatures seemed to cover the whole floor. There was a door open behind them into a comfortable bedroom, and a bright clean oilcloth on the floor of the kitchen; there was a gay little clacking clock on the high chimney shelf above the stove, with a pair of shining lamps. Everything was cheerfully clean and thrifty in the warm little place. and Mary Ann herself looked as if she were able to keep her housekeeping up to the highest standard.

"Well, there now!" she exclaimed with an almost ostentatious air of hospitality. "How are ye the day, Elleneen? I was after wishing you here a minute ago; how come you out?"

"I'm loafing for the afternoon," said the guest disconsolately. "There was something stopped wit' the machine-ry. I wish fast enough I was out altogether. I'll never get learnt, anyway; me mind ain't on it."

"Oh, go 'way!" responded Mary Ann vigorously.

"'Tis thrue for me. I'm getting pay now only for their being so short-handed; but me mind ain't on it nor in it, so it ain't."

Mary Ann made an inarticulate sound signifying contempt.

"I t'ought I'd come over an' give yez a lift wit' the houseworrk," ventured Ellen somewhat timidly.

"Well, I'm obliged to your kindness," said Mary Ann amiably. "I've enough to do, 'tis thrue for me. That biggest one, Hinry there, was roaring all night wit' the ear-ache, an' I'd small chance to sleep."

"Coom, Hinry, coom an' see Aunty Ellen," said the visitor, who was still standing, and turned now to show an interest in the three playmates. "Well, I'll go lay me hat in on the bed; they might be picking off all me feathers if our backs 'ould be turned."

"No, no, give it here to me; that Hinry 'd be on the bed after it aisier than anny place," exclaimed Mary Ann anxiously. "Give me your jacket too, an' I'll put them here, see, on the hook behind the door. Sit down wit' yourself by the stove an' rest a while till we tark a bit. What's all the news?"

"I'd rather be doin' something," protested Ellen.

"Well, I've me ironing most done," answered Mary Ann, "an' I'll be thinking what I'd best do next. Faix, I've enough of it. Hinry, there, ain't got a whole frock nor a dacint petticoat to put on. He's the torment, annyway."

The smiling Henry toddled over to his young aunt, and made an attempt at familiar speech.

"'Tis sweeties he do be asking for," explained the intelligent mother. "No more sweeties'll he get, the day, I can tell him!"

"Did you get nice sweeties the day, darlin'?" asked Ellen with ready sympathy as she lifted the solid, unwilling little shape to her lap, whence he promptly slipped to the floor again, to stand facing her at a safe distance, and be˙in a second series of perfectly unintelligible remarks.

"Pity for you, you 'ont learn to tark like a Christian; a great man of a shild like you!" scoffed his mother with assumed severity. "See how well your aunty can't get the sense of a word you say! 'Tis of the nice grocer man he bees tarking, that niver comes inside the door 'less there's a sweetie in his pocket for Hinry. Well, then you should have the pride to tark like other folks, as I'm always advising you."

Henry had not more than reached the age of two years, but he was evidently animated by a fiery spirit that served him well in the place of experience. He now stamped his little foot and protested loudly, but his elders went on talking over his head with perfect indifference, and presently he returned, not in the least sulky, to the lively company of the smaller baby and their friendly little dog.

"I'm sorry enough that I ever come out," Ellen announced regretfully, after a pause.

"Ain't you the big fool!" remarked the elder sister, who was well married and settled in a good tenement, which even afforded a best room and a magnificent piano lamp with a yellow silk shade, a wedding present given by her man's associates at the gas-house. "I never saw the half day I wanted to go back," she continued; "I might like just to see the folks an' make a little visit of two-t'ree weeks. Himself was having great tark last night about his own old folks, and sometime he'd get a couple of months off an' we'd go home. He'd like well to show Hinry there to his fader. 'What tark you have of goin' home like a lord,' says I to him; 'for mesilf I'd rather the money was well in the bank than spending it on them dirty ships goin' home.' I'd like well enough to see me mother too," she added more softly; "but John's a great boy to spend his money if I wa'n't sharp wit' him. I've deceived him that a good deal wint to pay the grocer's books that's safe in the bank this minute. Only last night he come home wit' a suit o' clothes for Hinry there, that was a good three sizes too big. I'm all put back wit' me ironin'; I had to go carry 'em back to the store this morning soon as me dishes was done."

"'Tis better than the stingy kind," sighed Ellen.

"Ain't you downhearted the day? -- Loafin' ain't good for you," said Mary Ann as she came briskly to the stove for a hot iron and stood for a moment holding it near her cheek. "Whisper now; what kind of a b'y was Danny, John's next brother, the one that they kept at home on the land? John has great tark of him bein' so smart; but he's far too foolish about his own folks, we all know."

"Oh, he's the lovely b'y; he's twice as handsome as John -- I ain't sayin' but John's good-looking too," responded Ellen with a lively blush. "Oh, I thinks very often o' poor Danny," she added softly. "We parted very angry, too, wit' each other."

Ellen grew rosier still, and the tears shone in her pretty eyes and were winked away, and then they came back again at once. "'Twas all me own fault," she managed to say.

"Well, there's no harm done," Mary Ann insisted kindly. "There's smart b'ys enough to be choosing -- pretty b'ys, too. Jerry Callahan was walking wit' you last Sunday."

"He's a great lout, so he is," said Ellen with sudden fury. "I turned down a street to get rid of his company. Great omadhaun!"

"An' Phil Carroll's a good fellow that come away from Mass wit' you on the Sunday before. Oh, there's little birds tells me everything; an' all the b'ys said you was the prettiest girl on the floor last Saturday's dance a week ago."

But Ellen would not be cheered. "'Tis aisy tarking, then," she answered gloomily. "'Tis all them fools has to tark about, is other people and what they does."

"John says his brother Dan's got his mind on some girl now; I don't know who it was told him -- "

"Oh, 'tis that tall Desmond girl at home, that lived on this side the road beyond Donnelly's. She always wanted him," said Ellen after a strange little pause, but the color all left her bright cheeks. Mary Ann did not look round, but seemed more than usually intent on her ironing work.

"She had money too, hadn't she?" Mary Ann persisted.

"Folks said it of her; 'twas from an old aunt in Dublin that she got named after. Some said it was forty pounds -- there was conversation about nothing else an' I coming away."

Ellen spoke slowly as if with much effort.

"What come between you an' Danny, then, if you liked him?" asked Mary Ann with the authority and directness of an elder sister and a married woman.

"'Twas me own foolishness; there ain't a day but I says it," answered Ellen mournfully. "I never thought of anny one but poor Danny, an' I never was satisfied till I'd find some way to tease him. He'd them honest eyes like John's, that'd be lookin' at you all the time like an old dog, and he'd take every word a girl said for the thruth, an' I wint too far wit' telling him he'd no wish for anny one but the Desmond girl since she got her money."

``Most like 'twas but forty shillings in the stead o' pounds," said Mary Ann consolingly. "Well, an' what happened then?"

"I'd given him no promise," said Ellen, more sadly still, "except 'twas in me own heart. I think I'll never see anny one in the world like Danny; an' he had the lovely patience wit' me for a grand while, till I plagued him too far an' we had a smitch o' tark that day on the road. All the way we didn't stop a bird from singing, we were so quiet ourselves, till I t'ought I'd tease him; an' he pled with me then like a priest -- would I turn away from him altogether and misthrust him so? An' I don't know ever since why didn't I give in, but I didn't, an' I turned an' walked off down the road from him, an' I thought ivery step I took he'd be after me, till I'd changed me mind so much I demeaned meseIf to look over me shoulder, an' he wasn't stopping where I left him at all, but going off like a soldier, most out o' sight. An' he wouldn't look back, an' thin I called loud enough to him, and afterward I went back of the furze bushes, so none o' the market folks would see me, an' I cried till all me tears was gone. So that's the ind; and I ain't the first girl, either, that was such a fool, but I wish I'd be the last."

"An' what made you come off then an' l'ave him? All the while since you come out I've said to John you wa'n't happy; 'twa'n't Ameriky displeased you, but something of your own was on your mind. You might have had the sinse to speak," said Mary Ann, with awful severity; "an' John makin' things worse with writin' home what admiration all the b'ys had for your looks an' your dancing."

"I was full to the head o' me wit' pride an' sorrow, an' I wouldn't let on I'd got hurted," said Ellen, "an' I come out to hide away from ivery one there, an' now I've told all. Ah, 'tis all done an' over. Folks would try to tease me, an' there was those would both fetch a lie an' carry one, an' fan the fire o' throuble. I listened for him whistling by night whin 'twas fine an' dark, as he'd always done when he'd waited a while after our little pets before, an' I'd run out to him then, an' we'd make up lovely what throubIes had been between us. But this time he'd no whistle left, an' they told me he was seen a good deal up to Desmond's, an' all that. Sometimes I'm glad I come away, an' sometimes me heart's broke that I was iver such a fool. He'd never speak to me again anny way; but I don't blame 'im ayther."

Ellen had now come to the point where she couldn't do without the help of a much fumbled little handkerchief. "He didn't come with all the neighbors to say good-by to me, an' I was lookin' for him to come an' stop me from it, an' I pretindin' to be full of laugh and very gay-hearted, so nobody'd carry him word, an' I thought the first month I was here I'd be getting a letter from him ivery day, or a word in somebody's letter to wish me luck; two or t'ree times I sint word to him with the rest, wishing him happiness and not making anny joke at all."

"You were the big fool," pronounced Mary Ann coldly, as she tried another iron with her wetted finger; "I've got no word meself but that for yez." She tried to look harshly at poor Ellen, who still sat crying. "Coom now, Elleneen, don't feel too bad; don't cry, Elleneen dear. This is the last iron, an' then we'll sit down an' make Hinry his two little petticoats when I've done me last pieces here, an' I'll make the tay early for the two of us. You'd better think of some o' the other b'ys, now that's all past." But Ellen only cried the more.

"'Tis plain enough now he don't care very much for anny one," said Mary Ann with cold decision.

There was a sudden noise in the room beyond, as if somebody protested at the last remark.

"Run quick for me, Elleneen," exclaimed Mary Ann; "'tis the little dog in there tipping everything over."

Elleneen ran, and Henry toddled after

her, and the innocent puppy after him." There was a shriek of

joy and the sudden appearance of a trig, hearty young man with

bright curly hair and a wistful face. Danny had been waiting all

the time, a suffering captive in the inner room.

"She saw you coming," humbly explained

the lover to his happy Elleneen a minute later. "'Twas Mary Ann

seen you coming on the street, sure, whin I was just getting me

directions how I'd go find you. An' she said if I come out

before she'd give me l'ave, she'd have me heart's blood. I

t'ought ivery nixt minute she'd break the news for us. Sure I

worked iver since to get the money for me passage. Don't mind me

harkin' to all the poor little sorrows, darlin'; sure 'tis

meself only loves you the more. Don't mind me for stayin' in the

room."

"Ah-h!" said Ellen, returning to her old sports as soon as she could speak, "'twas just like a stupid man! Sure, I'd been out o' me cage like a wild blackbird the minute I got sound o' your voice. Anny way, I've got the lovely pinance after me confession."

And Elleneen hid her face again in the

rough frieze coat, which still carried a homelike fragrance of

turf smoke, though mixed with the duller and more recent odors

of tobacco and the salt sea.

"Elleneen" first appeared in McClure's

Magazine (16:335-338) in February 1901, where it was

illustrated by G. A. Cowles. The story also appeared The

Idler of London (20:177-180) in September 1901.

Richard Carey printed the story in Uncollected Stories of

Sarah Orne Jewett. If you find errors or items

needing annotation, please contact the site manager.

[ Back ]

faix: faith.

[ Back ]

gas-house: A place where gas for

heating and lighting is prepared; a gas-works.

[ Back ]

omadhaun: a fool or imbecile from

Irish and Gaelic, "amadan."

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College.