Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

.

BY SARAH O. JEWETT.

On the Creaking Stair |

ONCE there was a little girl, who is a great girl now, whose name was Milly, and she was very fond of sponge cake.

Doesn't that sound as if this were going to be a good story?

And one day when she was playing with her dolls she found they had nothing in the house for dinner, and though it was a good deal of trouble she went down stairs to find something. There was no regular dinner-hour at the baby-house; the family did not seem to mind whether it was served soon after Milly's breakfast in the morning, or late in the afternoon. They always sat up straight and stiff, (except the yellow-haired doll in blue, whose head was always falling over into her lap) and were always pleased with whatever was said or done.

Milly was living at this time with her grandmother. Her father and mother had gone abroad to stay a year or two, and had taken her elder sister with them; and Milly was very happy indeed, for everybody in the house was very kind to her and gave her almost everything she asked for, and a great many pleasures beside by way of surprises.

It was a large, old-fashioned house, and most of the rooms were large except this small one, where the baby-house was, which opened out of the room where Milly's small bed stood alongside her grandmother's wide one. It was really her grandmother's dressing-room where she played, but she kept her playthings at one side of it; there was a stripe in the carpet which marked out her boundary, and she was not allowed to let her possessions stray over it; and she minded very well what she had been told about meddling with her grandmother's dressing things.

Only once there had been a dreadful afternoon when she had wanted some water to wash all the dolls' faces, and had tipped over the great pitcher. Nobody knew why it had not been broken, but it was very lucky, for it was a pitcher which grandmother thought a great deal of, and had had ever since she went to housekeeping.

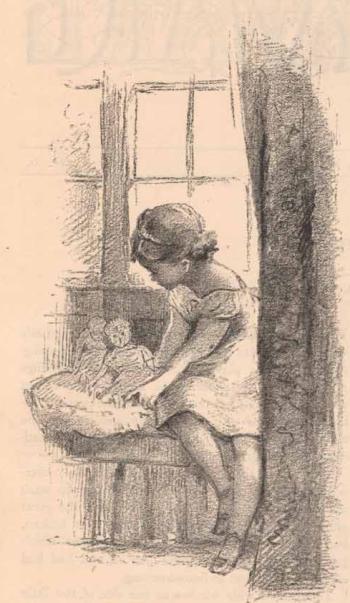

There was a wide window at one side of

the little room and though it was not on the play-house side,

Milly could sit there as much as she liked on the window-seat

which had a soft cushion and was very comfortable. She liked to

unfasten the heavy curtains that were looped up at each side and

shut herself in. You looked out on the garden from this window,

and just now the purple and white lilacs were in bloom there,

and the flowering currants had

faded and there were some tulips, and the peonies had grown tall

and green, and were topped with some hard, round buds. Just

below the window on a Norway spruce-tree there

was a robin's nest with some eggs in it, and Milly could watch

the bird as she sat there every day. It would be great fun to

see the little birds after they were hatched, and Milly's

grandmother watched them almost as much as she did, for she was

always pleased when the birds built near

the house.

In the Beautiful Window |

And now I have said this about the grandmother, and the house and the little girl so you may know them a little, I must go on again with the story of the day when the dolls had nothing for dinner.

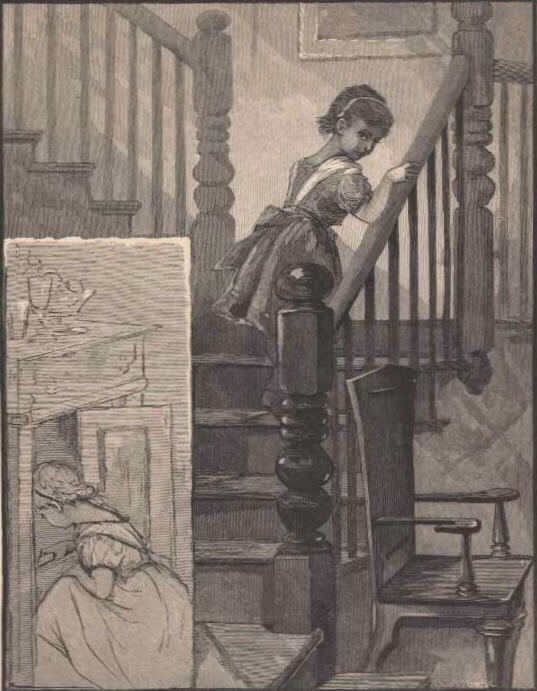

It was a hot day, and the blinds were shut everywhere to keep the house shaded and cool, and grandmamma was taking her afternoon nap in her own room so Milly knew she must not make a noise, and she opened the door into the hall as carefully as she could and went out on tip-toe, for the door into her grandmother's room was open. There was one stair that always creaked, but Milly could never remember which it was until she came to it; however it made very little noise to-day, and she went out to the dining-room.

There was a plate of little biscuits on the side-board which she could have whenever she liked; but somehow our friend did not care for them to-day. She listened, and the house was still and she could hear nobody coming. Nobody had ever told her not to go to the side-board [sideboard] and it could not be any harm to look in, still, she felt guilty as she turned the key of one of the little cupboards and looked in at the door.

Yes, it was the one where the cake-box belonged, and she stopped for a minute to think, as she often had done before, what a good place the side-board would be to play dolls in; it would be so nice to carry the key in her own pocket and lock and unlock the door when she pleased. Perhaps grandmamma would let her have this part to keep a few of her playthings in; and then she could stay there every afternoon for a while and need not keep so still as she had to in the dressing-room. There did not seem to be much in the little closet, only two blue-and-white ginger-pots with their cane-netting and twisting handles, and a brown jar which held some very sweet East India preserves which Milly liked better than the ginger, and on the shelf underneath was the cake-box, which Milly pulled out a little way and opened. There was such a pleasant odor in these side-board closets always; it made any one hungry at once.

There was a good deal of cake in the box; a great loaf of fruit cake, and two frosted loaves of pound cake, and half the round sponge cake that had been made for tea the evening before, beside some pieces that had been cut and not eaten. But Milly had been told she must not eat any cake unless some one gave it to her. She never must take it herself.

"I shall tell grandma I didn't ask her because she was asleep," she thought; "she always gives it to me," and she took two pieces out and locked the little door again and crept softly up-stairs. "I know grandma would say I might have it," she said to herself, but for all that she hid the cake under her apron, as she went, up, and the step half-way creaked so loudly that for a minute she was afraid to go on; but nobody spoke.

So Milly and her dolls had their dinner-party, but just when one piece of cake was eaten, except the bits that were in the dolls' plates, and Milly was taking her first bite of the second piece, Mrs. Hunt waked up and called her.

"Won't you go out to Sophie's room and say that I wish to see her before she goes out, my dear?"

Milly hurriedly put all the cake in her pocket, the dolls' platefuls and all, and went to give the message. Sophie was just putting on her bonnet and shawl, and Ann was sewing by the window. They were always very good to the little girl, and Sophie at once told her that she might go out with her. She was first going down town to do some errands at the shops, and then she meant to spend an hour with her sister.

Milly said she should like it very much, and hurried away to get ready. Just as she was ready to start she remembered the cake, and she did not know what else to do with it, so she opened one of her little trunks and put it in under the dolls' dresses, and then went away with Sophie, who was a tall, kind woman, who seemed almost as old to Milly as Grandmother Hunt herself.

Our friend liked to look in at the shop windows and Sophie waited patiently, so there was, after all, not a great while to stay at the sister's, who lived in a house whose back windows looked down on the river, and who worked all day making artificial flowers. Milly liked dearly to watch her; to-day she was making butter-cups, and she gave Milly some little blue flowers for a doll's [dolls'] hat. She sent the flowers away in great white pasteboard boxes when they were done; she was a lame woman and could walk only with crutches, and Sophie and she seemed very fond of each other. They were French women, though they had both been in this country a great many years.

Milly listened while they talked to each other, and sometimes she heard one of the French words which Sophie had taught her, and then she was very pleased; and she watched Marie make the buttercups with her quick, thin fingers, and indeed they came into bloom very fast. Marie was so used to making them that she seemed almost careless about it, and would hardly look at what she was doing, though every bit of yellow and green and every twist of wire was always put in its proper place.

By and by Milly went to look out of the window to see the boats go by; a buzzing, hurrying little steam-tug went up the river, spattering and leaving a white track of foam behind it; it made her think of a bumble-bee, and she wondered where it was going in such a hurry. Afterward some boys came along in a dingy, leaking boat, and threw out their lines to fish, but they only caught one little fish, which Milly hated to see flutter and throw itself about; the poor thing seemed so long dying.

They were just under her window, and at last they looked up and saw her and made such faces at her that she was very much pleased when she saw one of them tip the boat so much in changing his seat that the little fish, which just then gave one desperate flap, went over the side and into the water. The boys looked after it, and Milly laughed, but she put her head inside the window so they did not see her.

"What are you laughing [langhing] at?" asked Sophie; and when Milly told her she and Marie both came to look out, and Marie said she was glad they had no luck, for she did not like those boys. They would come to some bad end, she was afraid, for they swore so and were so saucy; and beside that they were thievish.

Now Milly had been feeling very much pleased with herself, but this reminded her of the naughty thing she had done, and the thought flashed through her mind, "What would Marie say if she knew I stole, too?" And she was so ashamed.

But Sophie and Marie had already forgotten the boys and were chattering French again; while Milly began to be afraid that grandmamma might go to the dolls' trunk, and she was in a great hurry to get home. Yet she did not like to say so to Sophie, who stayed some time longer; but at last they were on their way back. It was growing late in the afternoon, and Sophie walked fast for fear she should not get home in season. Mrs. Hunt liked to have tea ready at exactly the right time.

Milly went at once to the baby-house, and there was the trunk, which grandmamma had not thought of opening, which was a great relief, and the cake was inside, folded in the best doll's little shawl. She did not know what to do with it; she had a most guilty feeling; she wished her grandmother knew about it, and she ate it as fast as she could, breaking off one little piece after another, fearing all the time that somebody would come in; and she did hear a footstep at the last, and put the rest of the cake in her pocket just as Sophie opened the door and told her that tea was ready.

There was a basket of fresh cake on the table, and Mrs. Hunt, who was very fond of it, praised it and herself gave a piece of each kind to the little girl; but somehow Milly felt sorry as she took it. When tea was over grandmamma read her a letter which had come from her mother that afternoon, and there were a great many messages for her, and mamma said she was very glad to hear that Milly was such a good girl; which made her think again of the two pieces of sponge-cake.

It was still early, and it was so pleasant that Mrs. Hunt thought she would go to drive, and she took one of her old friends and they all went a long way up the shore of the river. It was very pleasant, but when Milly reached home she was so sleepy that Patrick had to lift her out and give her to Sophie, and Sophie took her up stairs and put her to bed, so that was the end of that day.

It had been for several days very warm and pleasant weather, and Milly had worn a thin dress, but when she waked up next morning it was cold and rainy, so that was put away and Sophie brought out a thick frock which was very comfortable. Milly played all the morning in the dressing-room, and she was not very happy. One by one each of the dolls did something that was naughty and provoking and was punished for it, until the whole baby-house was in disgrace, and so many things strayed out beyond the boundary stripe in the carpet that grandmamma said she must put the baby-house in order before she left it, for the playthings were scattered all about the floor.

"Isn't the little girl happy to-day?" said she, kindly; and Milly hung her head.

After a while she thought she would get some beads which were in one of her trunks and string them until dinner was ready; she had begun some time before to make necklaces for all the dolls. She had two little trunks just alike which two cousins had given her the same Christmas. It was very fine to have two, and she was very proud of them, but to-day she happened to open the wrong one, and there were all the crumbs of the cake scattered on top. She had forgotten it just then and felt a little angry, but she shook the little shawl out into her lap, and gathered the crumbs up in her hand, and then remembered that there was a window open in the next room and resolved to go in there to throw them out.

Just as she was on her way she heard her grandmother's slow step in the hall outside, and her little heart began to beat very fast. She was half-way across the room and very near her own little white bed, so she quickly put the little handful of crumbs inside, I do not suppose Mrs. Hunt would have noticed at all that she threw something out of the window; and she only said, "Dinner is ready, dear," and in a few minutes they went down stairs together. [,]

After dinner was over grandmamma took her nap and it was a longer one than usual, and there the cake crumbs stayed and dried.

One of Milly's friends came to spend the afternoon and drink tea with her, and so she forgot what was hidden in her bed until she was fairly in it. Sophie was very kind that night and tucked Milly in, and even sat with her awhile and told her a long story about when she was a little girl and lived in Paris and used to go every spring to make a visit to her god-mother who lived out in the country.

Milly was always glad to hear these stories, but that night the crumbs made her very uncomfortable. They scattered themselves all about the bed and were under her back, and somehow or other one or two got inside her nightgown sleeve and would not be shaken out. She moved about trying to find a place where there were none, and Sophie thought she was restless; but the more she moved, the more crumbs there seemed to be, and at last she was glad, for the very first time in her life, when Sophie bade her good-night and went away. She tried at first to brush the crumbs out of bed, but that would never do, for they would be seen on the floor in the morning, and so she stole out of bed, and got as many as she could in her hand and threw them out of the window. She was sure she had found them all, but when her head was on the pillow again it seemed as if there were more than ever, and she was very wretched and passed a most uneasy night, for she kept waking up and feeling the hard little bits, and a great wind blew all night long and made all the noise it could in the elms around the house; and if it had not been light enough to see grandmother sound asleep close by, I think she might have been afraid.

The next noon it cleared off, and it was warm summer weather again; the wind had come round to the south, and later, Milly's brown frock which she had worn in the morning was altogether too thick, so Sophie was told to change it; and Mrs. Hunt added that she was going to make a few calls in the neighborhood and Milly might go with her.

So the thin dress was put on, and she took fast hold of her grandmother's hand and went skipping along at her side, taking three steps for every one of Mrs. Hunt's sedate ones. She liked to go calling very much; the old ladies whom she went to see were always very kind and made a great deal of her, and very often gave her some candy. Milly thought old ladies were a great deal nicer than young ones; but to-day the first call was made upon somebody whom she did not like very well -- to tell the truth she was a little afraid of Mrs. Hirst, who was very wrinkled and very prim and forbidding, and who wore stiff bunches of little black curls on each side of her face. Grandmamma's curls were soft and gray and she had a very pleasant look, and always was ready to smile at her little girl.

Mrs. Hirst was very ceremonious, and she said "How do you do to-day, my dear?" in the most polite way, and gave Milly a hard little stool to sit on which was not pleasant to begin with, as our friend would have liked a chair a great deal batter if it were not too high. But she seated herself and listened while Mrs. Hunt and Mrs. Hirst talked to each other.

In those days it was the fashion for little girls to wear frocks that were made low in the neck and with short sleeves, and Milly's was made in that way. She had only worn a little silk cape with fringe round it, instead of her little cloth coat, and presently even this felt too thick, so she would have liked to take it off; but she did not know what Mrs. Hirst would think if she took off a cape without being asked, so she sat still with her hands folded, and gave once in awhile a quiet sigh.

But in a minute she felt something crawling on her right shoulder and brushed it off, but the next minute it seemed to be in the same place again, and she put her hand under the little cape and was afraid it might be a spider, only it seemed smaller, and there seemed to be more than one. At last she threw back her cape and to her dismay she found there was a long procession of red ants going over her shoulder into the world beyond.

There were dozens of them; they were coming up over her dress, and they were all in line; when she tried to brush them off they only came and came, each with a bit of white in its mouth; and she looked down with a chill of horror and saw that they were coming out of her pocket. If she had thought a minute I do not believe she would have put in her hand at all, but she did, and pulled out her handkerchief with the rest of the ants and a shower of cake crumbs.

If it had been anywhere else but at Mrs. Hirst's!

Luckily the old ladies did not [not

not] notice her, and she picked up all the crumbs she could and

held her cape close together and longed for her grandmother to

finish the call, and the little ants marched on, and Milly knew

she could not keep from crying a great while longer any way in the world.

Milly Wishes her Grandmother Would Hurry |

She had often heard her grandmother say what misery it was to have emmets get into one's house; she knew how angry Ann and Sophie were when they found them in the closets, and there were even times when Ann had had to put the legs of the table in plates of water and keep the sugar and some other things on it for safety. The dreadful thought came that Mrs. Hirst would have ants in her house, now, and would always be angry with her; she imagined her saying in chilling tones by and by:

"So this is the naughty little girl who brought the emmets!"

But Mrs. Hirst seemed unusually good-natured that afternoon, and even brought her little guest a round, frosted cake with red caraways on it, and when Milly said she could not eat it, it was put into a paper for her to carry home, but she did not put it in her pocket.

She was so afraid her hostess saw the ants and the crumbs, and she could hardly wait until they were out of her hearing on their way down the walk to the front gate to say in despair --

"Oh, grandma, hurry! please take me home quick, I'm all over ants!" and then she began to cry as if her heart would break.

Grandma shut the gate behind her, and looked down at poor Milly with great amazement.

"Oh, take off my cape, please do! They're all walking up over my shoulder out of my pocket! and they all shook out of my handkerchief on the carpet! Oh, dear, dear!" and Milly fairly danced up and down, she was so miserable.

Mrs. Hunt lifted the little silk cape and saw the procession, but it had almost gone by and was already straggling, and she could not keep herself from laughing heartily, though she pitied Milly very much.

"We'll go right home to Sophie, dear," said she; "but how did they come in your pocket?["]

And then Milly told the whole story.

Grandmamma was very sorry about it; it was not that she minded the cake being eaten, but Milly had done a thing which she knew was wrong.

"Do you think I can trust you any more, dear?" said she, and Milly with many tears promised that she would try to be good.

Grandmamma said she thought she had been punished enough already, and the little girl crept up into her lap and sat there a long time, and they made the rest of the calls another day.

It was a very good lesson, for she was so ashamed of herself and was made so uncomfortable that she could not forget it, and she tried to show afterward that she was fit to be trusted, for although she was a little girl she had learned that a person who cannot be trusted is not worth much.

I do not believe that Mrs. Hirst ever said anything about the emmets. Milly was always afraid she would, but perhaps there were emmets in her house to begin with and she did not notice the new ones, or perhaps they had been homesick and came back as fast as they could when they found where they were.

But a day or two afterward Sophie took Milly again to see her sister Marie, and Milly was sure she told her the whole story in French, for they laughed a good deal and looked at her sometimes as she sat by the window and looked out at the river and thought she never would take any cake from the side-board again without asking as long as she lived. She leaned over the window-sill to see the water so Marie and Sophie would not notice the tears in her eyes; but Marie was even kinder to her than usual that day, and gave her ever so many flowers to trim dolls' bonnets, and even showed her how to make a pink rose to take home to her grandmother, who was as much pleased with it as heart could wish.

And since then I do not know how many times she has laughed when she has thought of the ants in her pocket, though it was such a dreadful thing at the time.

Notes

"Cake Crumbs" appeared in Wide

Awake (10:331-336), June 1880. The table of contents

for this number indicates that Miss L. B. Humphrey was its

illustrator. Lizbeth Bullock Humphrey (b. 1841) produced

illustrations for many popular books, including books of

children's poetry and the first American edition of Alfred, Lord

Tennyson's The Song of the Brook, and won Louis Prang

prizes for her Christmas card designs.

This text is available courtesy of the Colby

College Special Collections, Waterville, ME. Errors have been

corrected and indicated with brackets.

[ Back ]

flowering currants ... Norway

spruce-tree: Currants are small bush berries, red, white,

or black, that are dried and used like raisins. Norway spruce (Picea

excelsa) is a tall-growing, northern European spruce.

[ Back ]

East India preserves:

Imported from the East Indies, e.g. India, China, Japan or other

areas in the region.

[ Back ]

emmets: an archaic word for ants.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College