Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

.

THE CHURCH MOUSE.

BY SARAH ORNE JEWETT.

HAD you been waiting at the entrance

to the First Church of the town of Dexter, on a certain Sunday

morning in December, you would have seen a curly haired boy come

running up the street in a very week-day fashion. He pushed by

some orderly and inconsiderate persons who were taking up a good

deal of room on the sidewalk, as if he were in a great hurry,

and scurried up the church steps at last, and disappeared behind

a little door which led to the organ loft and the belfry.

The organist had begun to grow uneasy. He had been listening for some minutes for the creak of the organ bellows, and had again and again touched a key gently, in hopes that he might have missed hearing the boy come in, and that his instrument might already have got its breath.

The minister arrived a little earlier than usual, and wondered why he was allowed to walk up the broad aisle unheralded by the beginning of the voluntary. The parishioners looked around one after another to see if they could discover the cause of the silence, but there sat prim old Mr. Edwards on his perch, with his back to the congregation, as if it were none of his fault. He was the chief music master of the town and had played the organ of the First Church for more than thirty years -- a very good little man indeed, though sometimes short tempered, and he wore a nice curly wig of a reddish tinge, as was suitable for a person of his disposition.

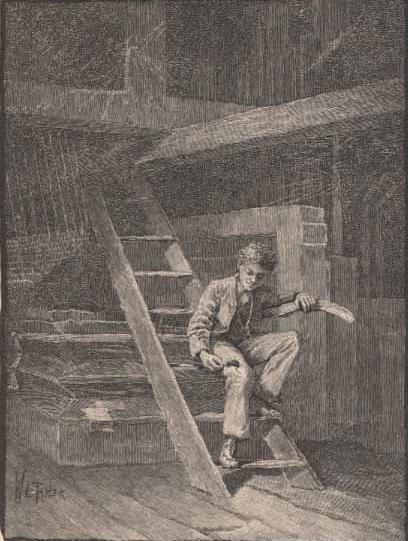

He sat before the silent keys, growing more and more disturbed, but the singers whispered together near him, and he did not hear Tom Lester come up the stairs, and left his finger upon one of the keys that presently sent forth a high, sharp note as the organ filled with wind. Tom worked away at the bellows as hard as he could, and Mr. Edwards began to play, somewhat angrily, giving the melody a reproachful expression, but all anxiety was at an end, and the church service went on in its usual fashion. Tom Lester sat on the broken-backed chair in the dusty little organ loft and gradually cooled off after his hard run, and took a long breath as the old organ had just done, and then sat looking about him.

There was a great deal of dust everywhere and all the church spiders of that summer and many others had spun their webs and caught their flies unhindered. The back of the organ was very unlike the front; it was a rough-looking thing, and one would never have believed that any music would come out of it. The front was very fine, although it was an old and rather small organ, for it had shared in the general restoring of the church not long before and had been varnished and gilded in its woodwork and pipes. It made Tom think of some of the houses in Dexter, that were quite grand on the street side and quite uninviting as viewed from the back alley.

He found the interior of the organ very interesting, for ever since he had discovered that it was the habit of the tuner to creep in to tinker at the pipes and stops, he had followed his example from time to time during his seasons of leisure in the long sermon. There were a good many little shelves and ledges in the woodwork, and Tom had stored away many of his belongings for safe keeping. It was sometimes awkward to have to wait from Sunday to Sunday to get some treasure or other.

Tom did not like to go to church in the evening. There was always a service at that time, but the sexton, who was a grumpy person, and who prided himself as he should, on being very careful, would not allow a lamp to be carried into the organ loft for fear of fire. Some light came through the chinks between the pipes, but Tom sat in a dismal twilight, except when the full moon shone through the odd-shaped window over the front door of the church. The sexton sometimes opened the door at the foot of the crooked belfry stairs while service was going on, but he quite as often forgot it.

As for the preaching, it was difficult to hear it clearly, and Tom was not apt to be a devout listener, at any rate, but the music he loved dearly. From the first he had listened delightedly to Mr. Edwards' playing, which was, to tell the truth, uncommonly good. He knew most of the voluntaries by heart; he liked, as he would have said himself, to hear the old organ creak and sing with all its might, and beside, he had his favorites among the psalm tunes, and used to hum them to himself softly, and even take an unsuspected fifth part in the quartettes.

On this Sunday morning he did not take much notice of the music, though after the first angry notes the organist's fingers had touched the keys more gently, and when the last strains were finished Tom went on blowing until he found the lever refused to make another downward stroke and the aggrieved instrument began to groan of its own accord. The minister made a short prayer and then began to read the Bible to his congregation, to which everybody lent an ear but little Tom Lester in the organ loft. He sat still for a minute or two, and then went to one corner of the organ framework and got down on his hands and knees before a mouse-hole. So far as one could see, it was the doorway to a deserted residence, but Tom put his face down as close as he could and made a soft little chirruping noise with his lips, and then he leaned back again and watched anxiously. There was always a time of suspense and fear lest something might have happened to his small friend, and before any answer came to this summons, Tom noticed that the minister's voice had ceased and he took his seat again to have the organ ready for the singing of the first hymn.

But that was hardly over when something appeared in the mouse-hole -- the church mouse itself, with bright, bead-like eyes, and it came out to the very tip of its tail, and looked at Tom, who nodded and pushed one foot toward it playfully, but it did not run back into its hole again; it ran toward the foot instead and climbed up the trousers leg, and Tom poked its back with his finger and pushed away eagerly with one arm at the bellows, as if he thought he could hurry up the hymn, and with the other hand he fumbled in his pocket and pulled out the very piece of bread which had made him late to church.

For you see he had to run back just at church-time to Mrs. Dunn's, where he lived, to get it, since he had for once forgotten to save it from his breakfast. But Mrs. Dunn had locked her door behind her and gone out, and then he went to the Duncans' where he sometimes did errands, and though he pounded and rapped away at the back door, the two good-natured Irish girls had gone to mass together, and Adeline, the nurse, who was keeping house, was sitting at the parlor window, under pretext of amusing the baby, watching new winter bonnets and cloaks go by. And there Tom was at his wits' end. The bell was tolling its very last strokes, and he started to run to the church with a heavy heart inside him because he should disappoint the church mouse of its Sunday breakfast. Whom should he see at this unhappy moment but little Nelly Jacobs, the old watchmaker's grandchild, and she stood just inside the gate of her small side yard, eating a large piece of bread and butter.

"Oh, give me a piece of that," says Tom in a tone of command, and because he was a big boy and not very friendly looking, she obeyed, and he stuffed the hastily broken half-slice into his pocket and ran on well satisfied, for he told himself that she could get plenty more where that came from, and he would do her a good turn some day as payment.

Now I should like to tell something about the previous history of Tom Lester, and also of his friend the church mouse. Having presented them both to the reader, we will imagine that the long sermon has begun and that Tom has broken the bread into a great many small bits and laid some of them in a long line on the floor. The mouse has eaten two, as if it were very hungry, and has since been industriously carrying them down into its hole to stow away in its larder, wherever and whatever that may be. Tom has wondered why it would not be just as well for them to be left where they were, in fact, he used to have surprises for the mouse just before he left the organ loft, until it came to his mind that there might be other church mice, and that they, and not his friend, had found the bits of bread and cheese that he had carefully placed on the little ledges of the organ, both within and without.

To tell the honest truth, Tom himself was a church mouse as much as if he had four legs and a furry back, and lived down in a hole and gnawed hymn books. His father was dead, and his mother was dead, and he had no brothers or sisters. His mother had been a good and useful woman, and a respected member of the church, and when she died, after a lingering illness, it was promised her that her child should be looked after, and provided for, until he could take care of himself. So while he was very small, his board was paid, and he was sent to school; but within the last year he was thought able to earn part of his own living. The organ boy's family was going to leave town, and Tom was put in his place, which made a saving to the church, because his salary went toward paying his board. He did himself great credit, too, it being his first public position, and he held out splendidly against the bribes offered by some of the boys at school, and refused to open the church doors to the rascals who wished to ring the bell from twelve to one o'clock in the dead of night before the Fourth of July. It must be confessed that on the second Independence Day of his term of office, he did not prove so staunch against besiegers, and Old Norris, the sexton, never has known to this day how the boys got up into the belfry.

Fourth of July was on Monday that year, and Tom came boldly down the belfry stairs and went out of the church front door Sunday night, but while Norris went back up the aisle, to blow out the pulpit lights, our friend crept back again and went up with two cronies, and all three hid themselves, in the twinkling of an eye, in the cobwebby organ-loft and up the belfry stairs.

Such a pealing as the old bell gave three hours later! They turned it over and over, and hustled it dreadfully, first one and then another tugging at the rope, until Bob Larkin was overtaken with a perilous attack of bleeding at the nose, and the noise of firecrackers and the light of bonfires proved so enticing that they went tumbling down the crooked stairs again, and let themselves softly out of one of the well-fastened windows to the ground.

But I must assure you that little Lester was seldom found fault with, and besides his church duties he did errands, and light work in the gardens, and was growing up fast, and almost every dog in town would run up to him or wag its tail when it saw him, and he whistled at the canaries as they hung out-of-doors in the summer, or patted the horses' noses, and gossiped with the two or three wicked old parrots who had long since lost their claims to being strangers and foreigners. In short, he was very fond of animals, and was always good friends with them -- and I suppose this was the reason he had become so particularly intimate with the other church mouse.

Indeed, it was a tame creature; it would run up his jacket sleeve and down his collar, and squeeze itself into the smallest possible cracks and crevices, and would hide away in an instant, and puzzle Tom astonishingly while he tried to find it, and then in another moment it would appear again, with its shining little black eyes looking up fearlessly into his. Tom had seen it peering out of its hole one day, as he blew the organ, as if it wished to inquire what all that noise was going on about. It was very young, then, and had not learned the dangers of trusting human kind, so when Tom found some crumbs in his pocket, and threw them down, it darted back for a moment into its shelter, and then, strange to say, came back again and took possession of a bit of gingerbread which had fallen at the edge of its door. Next Sunday it was not to be seen, but it found the fresh crumbs a little later, nevertheless, and perhaps it remembered Tom, and perhaps it didn't; but it is true, at all events, that in course of time, it was as tame as he, and one was no more afraid than the other was.

But, on the contrary, a friendship grew up between these two that would have caused great surprise to such persons as are terrified at the sight of a mouse, and who even jump upon chairs and shake their petticoats, and shriek if one is so much as spoken of. Tom fed his mouse generously; you could not say poor as a church mouse, and have meant that one. He really kept it in great luxury, and there was no excuse for the bad habit it had of gnawing the leather backs of the choir-books, and even the hymn-books in the pews. It had travelled, on one occasion, as far as the pulpit, and had taken a sinful nibble at the cover of the great red Bible, which had been the gift of a deceased parishioner a great many years before. This was so very small a nibble as to be unsuspected -- for the morocco was very dry and bitter to the taste -- but Sexton Norris, who might well play the character of church cat, at last discovered the other depredations, which were also spoken of by different members of the congregation, and set a trap, well baited, for Tom Lester's church mouse.

"It's them Downing children," said the old sexton indignantly. "One would think that they could get time enough to eat without keeping it up all through meeting time; but they munch candy and sweet stuff straight along -- and that's what draws the mice in, plague take 'em!"

So, on this December Sunday morning,

while Tom Lester blew the organ, and played with his small pet

by turns, his heart was very heavy, for he feared as he strewed

the bits of Nelly Jacob's bread on the floor, and watched the

quick creature whisk them away, that it might be the last time

he would ever have the mouse for company. He was a lonely boy --

and would have loved a real home dearly if he had had one -- and

since he was only a boarder and a pensioner, and a church mouse,

he took his bits of homelikeness wherever he could find them.

And as he had opened the door that morning at the foot of the

belfry stairs, his heart had sunk at the sight of a great

old-fashioned mousetrap all ready for service on the second

step. It seemed a cruel thing to make war against so tiny and

defenseless a creature, and Tom racked his brains to think how

he could save it from destruction, while he hated Old Norris

more vigorously than ever.

It was the Sunday before Christmas, and before the sermon began, Tom heard the minister ask that the contribution which was to be taken up for the payment of the debts which had been incurred in shingling and painting and decorating the old church, might be a very generous one; indeed, he hoped it might be the last. Also those persons who were ready to hand in their money subscriptions for a Christmas supper might do it that day, envelopes having been provided in the pews.

Presently there was a clinking of silver in the plates as the deacons went up and down the aisles, and Tom could hear it where he sat, and he wondered if he should have as much money when he grew up, and what he should do with it, and what was likely to become of him anyway. He wished that he belonged to somebody, like the other fellows. He wondered what he should do about that mouse-trap, for it was the kind that chokes and kills -- a trap to be dreaded and feared.

There seemed to be nothing to do but to hide away, and then after Old Norris had gone home, to take the bait from the trap, and get out of the window afterward, as he had on the Fourth of July. Accordingly, he came to church dutifully for the evening service, and as he came early, he had time to pick out the piece of cheese, and the wire caught his fingers and hurt them, which made him all the more intent upon marring the sexton's plot.

The service went on as usual, and Mr. Norris had good-naturedly put the lantern half-way up the stairs to make it pleasanter for Tom. The lights in front of the organ shone through the pipes, and made long stripes of brightness and shadow on the unfinished wall behind. Just before service began Norris put his head inside the door and called our hero in a loud whisper, and told him to mind his steps coming down, for there was a trap he was going to set in the aisle after church was over. Tom could hardly keep himself from laughing aloud -- that bungling Old Norris! -- and here there was a minute of silence, while the noble sexton held his trap up to the light and found the cheese was already gone. Tom's spirits rose as he heard the grumble, and thought that his mouse was safe until next day, at any rate. Perhaps he could damage the spring so that it would not catch! But just as this wise thought flitted through his mind, he heard the door shut, and when he snatched his first chance to go down, he found the sexton had taken the trap away.

The boy grew sleepy, and was glad when the last hymn was sung and he could go. Often the organist and even Old Norris, had asked him why he did not come down from his dusty corner while the sermon was preached; but there was a sense of freedom there which could not be enjoyed in the pews. As he descended, having left a good store of bread, and the stolen bit of cheese, beside a piece of apple for his small defendant, Old Norris stopped him, and asked him to wait a minute. There was often some help needed about closing the church, and Tom went inside the inner door to seat himself in the back pew to get out of the cold.

The minister tarried to speak with some people who waited for him as he came down the aisle, and last of all the sexton stopped him.

"I don' know what the folks will say," announced Norris, in his odd, gruff voice. "I don' know 's we could do any better, neither. It's the collection money that was took up this forenoon. Deacon Tasker always carries it off, and counts it over, and sees to it; but you may remember he was called out o' meeting just toward the end o' the sermon. I stopped here a while, thinking likely he'd be back after it, but I didn't see nothing of him, and I wanted to get home to dinner, so I just unfastened the little cupboard under the pulpit, and set the plates in there, top of the communion chist. I didn't want the charge of it -- you know I always keep one key, and the deacon the other -- in case of fire or anything. I s'pose there's no need to do anything about it? I'll open the door in two minutes, and get it out, if you say so. Mis' Tasker's mother lays very low. I s'pose you know all about it? She had an ill turn this morning, somebody was saying. I don't think likely the deacon means to come back to-night; it's quite a ways to Plainfields these short days. But perhaps you'd better take the money?"

"Oh, no," said the tired minister, shivering all this time in the open doorway. "It'll be as safe as the bank, and you can remind the deacon of it, or bring it to me if he isn't home by nine or ten o'clock in the morning."

Tom heard all this, but nobody noticed him -- indeed the sexton almost forgot him, and then was savage because he was suddenly reminded of the trap. "You just stop here five minutes whilst I step across the road for a bait of cheese," he said; "I promised I would see to those pesky mice." But when the old man returned he was hardly surprised to find no trace of Tom. The outer door was shut as if he had been tired of waiting and had run away. Norris had been delayed; his wife had gone to watch with a sick neighbor, and after scolding a little while he put the cheese in its place in the trap, and after he put that instrument of vengeance on the floor in the broad aisle, he scuffed about -- the honest old fellow! -- blowing out the lamps one after another, until the church was dark, and then he took his lantern and locked the door and went away home. The fires in the great stoves at the back of the church were burning low -- there was no danger in leaving them to quietly fade into ashes.

Tom listens from his hiding-place in the organ loft. It is very dark, and the church seems very large and empty; it is not half such good fun alone as it was with the other boys for company on a summer night. But he thinks of the mouse's danger, and goes bravely down into the aisle and feels about all the way along, and wonders if he will have to hunt in all the pews, and stops as he hears a footfall outside in the street, and then suddenly his one foot strikes the trap and he hears it spring, and laughs softly as he picks it up and again steals away the bit of cheese. He goes back again and throws it up into the organ-loft, and thinks with joy how angry Norris will be and what a good breakfast the tame mouse will have; and then he goes to the window from which he can step out to the top of the low horse sheds.

The window is fastened tight and

close. He feels it carefully after he has pushed and pulled and

shaken it, and finds that the careful old sexton has nailed

some slips of wood alongside, and has

made it fast against the winter weather. The church is built on

a hillside, and the other windows are all high from the ground.

TOM AND THE CHURCH MOUSE. |

So there was nothing to do but to stay all night, and after being perfectly sure he was going to cry, Tom told himself that it would be warm enough, and he could be let out in the morning, and after considering the situation, he went up into the singers' seats where the benches were wide and well cushioned, and laid down with his head on his arm, and tried to go to sleep, until presently he succeeded. If he had not been such a lonely little fellow he would have been missed. Sometimes he spent the night where he had been boarded in his early childhood; so each household thought he was with the other, and neither missed him.

While he slept there, the church growing colder and colder, and the starlight glistening brighter and brighter on its frosted windows that winter night, Tom dreamed about the mouse-trap, and thought he heard it snap and catch his small pet in its firm hold. He started up and did not know where he was. The strange bluish light of the great square windows was very awful, and strange to say, the snapping of the trap seemed to go on. Then he was wide awake, and found that the noise was at one of the windows, and he wondered if the boys had come to let him out. No; it was somebody breaking the panes. He heard the glass shiver and fall inside, and he listened until he heard voices whispering.

What could robbers want in that empty church? He wondered more and more, and for answer he remembered the little closet under the ponderous old pulpit, with the chest of quaint old solid silver which some rich man had left the First Parish when he died a hundred years before. Tom had seen part of it taken out and set in order a great many times. And beside the contribution money was there in the two plates, as Old Norris had left it. He wished he were in the organ-loft, but the door to the stairway opened and shut with a whine.

This is what he does: He waits until the two men on their evil errand creep in at the broken window and go up the aisle with a muffled lantern that seems to leak a little light as it is carried along. Then Tom pulls off his shoes and leaves them, and half slides down the few steps from the singers' seats, and along the aisle to the open pew door, and scrambles out carefully through the window, making only one click as he does it. The thieves stop in their work, but presently say to each other it was only a piece of glass falling from the sash, and go on prying open the little door.

And Tom is running down the street. He pulls this door-bell and that; in a very few minutes he has waked up John Fastnet and Henry Dennett, and two or three others, and has told his story, and they dress in a hurry, and take a pistol if they have one, and are out in the street, and before long a small company of strong men are in the old meeting-house and up the broad aisle, and the thieves are caught. As for Tom, he has been running about at the edge of the crowd, frightened enough, and at last his feet are so cold he thinks of his shoes, and after the robbers have fought and been mastered, he goes into the church and comes out again with his shoes, sees what else is to be seen, and then goes home to bed.

But in the morning he is well remembered, and is almost afraid at first to tell why he was in the church, but at last is made to confess about his dear church mouse, and some of the listeners laugh, but one kind-hearted man, whose grandfather it was who gave the silver, makes up his mind to look after the lonely boy, and so Tom has won a good friend by his night's work.

There is something else to be said after I have told you about a suit of clothes that the ladies of the Sewing Society made for Tom that winter -- even to the pocket handkerchief and as many stockings as if he were a centipede -- and that is he was sent to the best school in town by Mr. Duncan, and promised a place in his office later if he did well.

The mouse was an object of great interest that winter, and people insisted upon going up into the organ loft to see it, but it was frightened away by so much attention. Tom fed it and teased it out of its hole when he could, but at last it came no more, and the chances are that it found its life very dull, and longed for constant society and daily provision of something beside hymn-book covers. So it strayed out of the open door on a spring evening, and now follows the dangerous career of a ravaging house mouse.

Just at that time Tom became the proud

owner of a puppy, so he missed his former playmate less than one

would suppose -- though the puppy behaved disgracefully the only

time it was ever taken to the organ-loft, for it whined every

minute while Tom blew the organ for the voluntary -- and caused

great amazement in the congregation.

Notes

"The Church Mouse" appeared in Wide

Awake (18:155-161), February 1884, with an illustration by

W. L. Taylor, and was reprinted in Plucky Boys, 1884. This text

is from Wide Awake; it is available courtesy of Colby

College Special Collections, Waterville, ME. William Ladd Taylor

(1854-1926) was a popular illustrator for The Ladies' Home

Journal and other magazines. Some of his best work is

collected in Our Home and Country (1908).

[ Back ]

voluntary: a solo piece of music

played during a religious service in Christian churches.

[ Back ]

Fourth of July: The annual

celebration of the Declaration of United States independence of

July 4, 1776; also called Independence Day.

[ Back ]

morocco: Morocco leather is made

from goatskins tanned with sumac, hence the typical red color,

originally produced in Morocco (and other Barbary states) and

afterwards in the Levant, Turkey, and now in Europe from skins

imported from Asia and Africa; it is used particularly for

bookbinding and upholstery. (Source: OED; Research: Travis

Feltman)

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College