Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

The Green Bonnet: A Story of Easter Day

To begin with, Miss Sarah McFarland had not thought well of the bonnet she had worn all winter.

It was a presentation bonnet from an aunt who lived in Boston, and was therefore entitled to proper respect; but if the aunt, who had presented it the autumn before, not without parting pangs and a sense of great generosity, had seen how many times the present owner had angrily ripped off the feathers and moved them from side to side, and curled them with the edge of the scissors until they looked thinner and thinner and more and more spiritless, she would certainly have sighed over an unappreciated gift. There are many advantages about ostrich plumes but now and then some wilful relics of those energetic birds refuse to curl or to curve, or to look anything but flat or forlorn.

So all winter long Miss Sarah McFarland, aged eighteen, had never gone to church on a single Sunday without regret at her own appearance, and the green velvet bonnet had got many an angry glance and pettish shake. Sarah was always more or less conscious of being a horrid spectacle of tastelessness to the rest of the congregation. She sometimes had so keen a sense of those worn-out feathers which topped her pretty head that they felt as if they had stems that came through like sharp pins.

It was really such an awful old bonnet for a girl to wear; poor Sarah began to feel as if it somehow made her look more and more like the aunt who had given it, and who was anything but a beauty. The fact that she owned a good house in Boston and could do many things for her namesake did not make her any pleasanter, either. She was not likely to do the things a person wanted done.

But Sarah's father had very little money, and there were four girls younger than she. So she forbore, as she walked to church, to give unnecessary glances at the shadows of those sprawling little flat feathers on the snow.

--

There were almost no ways for a girl to earn money in Walsingham. It was a large township among the northern hills, with scattered houses and only one group which could by any stretch of imagination be called a village. This was composed of the church, Mr. Bent's store where the post-office was, and the blacksmith shop, which was a shop of high renown. John Tanner, the blacksmith, was almost a man of genius; that whole region of country depended upon him. He had taken the business at sixteen, when his father died, and now at twenty-four or five he was one of the best known men in a large neighborhood.

Everybody said that, with his instinctive knowledge of machinery and his power of handling metal, he should have been a trained mechanic. He had some artistic gift, but there was little chance to exercise this except now and then in a handsome pair of wrought-iron hinges for a barn door, or a really beautiful bracket which he once hammered and twisted out to hold a lantern which should light the meeting-house steps for Wednesday evening meeting.

John Tanner and his mother lived in the comfortable story-and-a-half house beside the shop and opposite the church. She was a hospitable, motherly soul, full of generosity. They were very well-to-do, and every Sunday noon she was sure to have some friends to dinner between the morning and afternoon services. Sarah McFarland's mother, a hard-worked, delicate woman, was often invited, but Sarah herself and the younger girls took care of themselves, being so young and active. They lived only a mile and a half from the church, which was not so far, after all.

Distances were great between house and house in Walsingham, and almost every farmer had a great deal more land than he could manage - almost all the timber-land had been stripped and left the country dreary. Sarah's father was one of these poor farmers, and it seemed hard to everybody that instead of a growing family of stout boys to help him work on the land, he had only his five girls; and it was often said that Sarah, the eldest, would have been so much more help if she had been a boy.

It seemed to everybody that Sarah was growing prettier every day, and toward spring, in spite of her youthful sorrows, and even the shadow of mortification which attended the Sunday church-going, her bright beauty attracted much public attention. In the old days everybody went to church regularly, both morning and afternoon, and stayers at home were carefully accounted for; but in these days you could choose between morning and afternoon, and there was general disappointment among the older people if Sarah McFarland did not come up the aisle. Beauty is beauty wherever it is, and shines brightest in a dull place like Walsingham, where one has so little in any house to delight the eye.

But when Sarah, in the old-fashioned velvet bonnet, thought of her despised head-gear and blushed for shame and sorrow, it was the moment when she looked prettiest, and made a thrill of pleasure in the country church. She was a good child, and many a dull-looking old farmer, sleepy with a hard week's work, got more delight in looking at her than in the whole week besides. As for the young men, there were very few to share this pleasure. They went away as fast as they could, just as the girls did, to get something to do in the larger towns. Sarah herself was going to Boston to live with her aunt as soon as her next sister could take her place at home. They had a milk farm, and there was a great deal to do. Ethel was a good scholar, and this was to be her last year at school. Sarah did not care much for the prospect of being with her aunt, but the reader will not be surprised to hear that she had views of learning the milliner's trade.

Spring seemed to be coming early that year; the sap had started in good season in the maple-trees, and the snow was going off steadily. Easter was neither very early nor very late, and winter was departing with unusual gentleness. The weekly newspaper spoke of a very early spring indeed, farther south in Massachusetts and Connecticut, and told wondrous tales of first bluebirds and the astonishing flight of wild geese.

But in Walsingham there was plenty of snow in the woods and along the fences. The renewal of life along the fields, the bloom of color in the wintry thickets, the reddening willows and the brown buds gave the some old pleasure and sense of springlike hopefulness. After a day or two of warm rain and the swift departure of both frost and snow, the brooks began to run, and the children began to play beside them, and all the wagon-wheels in Walsingham seemed to be trying to see which should carry the most mud on their spokes.

It was the first week in April. Easter fell upon the eighth; and in spite of the muddy roads the weather was so lovely that everybody, old and young, began to venture out to pay visits or to do errands. It had rained so hard all day on Sunday that there were very few people at church, but by the quick and efficient means of telegraphy which prevail in country neighborhoods, it was hardly Monday noon before the most remote farm in the parish heard the news that the minister was going to have an Easter service, and a Sunday-school sermon.

Many young people were summoned to the parsonage Tuesday and Friday and Saturday nights to practice, and already the minister had sent Sarah McFarland a long piece of poetry, that she might have time to learn it. She was by far the best speaker among the young people, and had often figured in both school and Sunday-school to the delight of everybody. She had a clear, pretty voice, and she gave the lines she repeated with a good deal of natural dramatic talent. You never thought how well she spoke, but only how beautiful or interesting the poetry was, which is the best praise one can ever give.

The messenger who brought the book was Mrs. Martin, a lively, talkative person, who lived near the parsonage.

"Seems as if we were right on edge o' summer this warm day," she said, unfastening her heavy shawl and unbuttoning the winter jacket under it.

"Yes," said Sarah McFarland's mother, "but you do right not to dress too thin driving in this damp air, Mrs. Martin."

"I must be thinking of spring," returned the guest. "I hear there's goin' to be a number o' new spring bonnets appear out on Easter Sunday. Mis' Folsom got hers, and so did her sister, Mis'Pease, when they were to Portland, and they said 'twas earlier than usual to lay off winter things, but they didn't know but they might wear 'em if it continued pleasant like this. 'Twould sort of mark the day; and I've heard of others."

Sarah McFarland's heart felt as heavy as lead. It had never occurred to her that the looked-for happy day of change had already come, when she could stow away that obnoxious old velvet bonnet and hope that every moth in Walsingham would get a bite of it before another year. But she had nothing to wear in its place.

She kept giving eager glances at her mother, the quick color kept coming and going in her cheeks during Mrs. Martin's visit, and she listened only with half-interest to the plans for the Easter service in which, it seemed, John Tanner, as well as herself, had consented to take part.

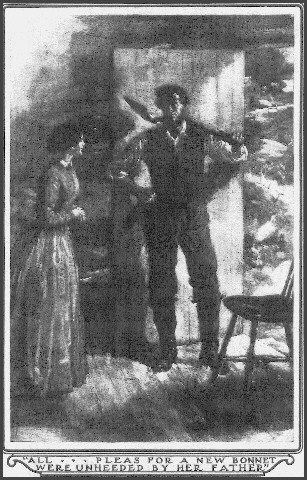

All our heroine's pleas for a new bonnet were unheeded by her father, who said that he was hard pressed for money, and she must wait for what she wanted until the first of May. He was not a stingy man, but Sarah was old enough to know that he was hard pressed oftentimes.

She gave a quick sob of disappointment before she thought, and said, "O father, I wouldn't tease you, but I've got to speak Sunday, and stand right up in front before everybody in that dreadful old bonnet of Aunt Sarah's. It does look so, father!"

John McFarland turned just as he was hurrying out at the door and looked at her kindly.

"I think my little girl looks pretty in anything," he said.

Then both felt very shy, and he hurried away still faster, stumbling down the step after he spoke.

Sarah felt only half-appeased then, but it was something she was going to remember with happiness all her life long - her father's speaking so.

The days flew by until Saturday, and the spring weather held to its bright intent; sometimes the soft mist covered the country and hid the distant hills, and then the spring sun came out again.

Sarah had learned her long Easter poem and they had had the last rehearsal the night before. John Tanner had a beautiful tenor voice and was going to sing a solo. People talked of nothing but the Easter service.

--

It has already been said that Sarah McFarland had four younger sisters. The two elder ones were steady, school-going girls of twelve and fourteen; and then there was another pair much younger, of whom the larger, Esther by name, was a naughty person. She had now reached the age of seven years, and there was hardly a day that she did not lead little Eunice, a mild and timid child of five, into some sort of danger and mischief. They were too young to walk all the distance to school, but Mrs. McFarland said that Esther must go with the elder sisters when the summer term began.

One of Esther's last diversions had been to build dams in a neighboring brook, which was now in high flood. Now, when she was kept indoors because Eunice had got such a cold that it almost threatened the expense of a doctor, she had begun to play gaily that she was grown up and wearing trains.

Mrs. McFarland found her own best dress parading to and fro in the long wood-shed. Esther's head was high in the air, and as she turned to behold the regal appearance of the train behind, which was already adorned with a fringe of little pine chips, she trod perilously into the front breadth at almost every step. Mrs. McFarland rescued the dress and spoke sharply to Esther, who couldn't quite understand such a needless excitement, or why she need be called a little torment.

"I will get something o' Sarah's," she said. "Sarah is real pleasant, and I'll play out-o'-doors again this afternoon. Eunice has got to stay in." Later this bad little girl departed toward her favorite play-place in the pasture, clothed in a summer dress of her sister Sarah's, which she had, with unusual thoughtfulness, pinned up into clumsy festoons. She also wore the green velvet bonnet; set very much on one side, and the worn-out feathers flapped weakly as she ran.

The bonnet lurched about, and if it had not been for the glory of being dressed up like a grown lady Esther could not have borne it on her head so long.

Presently, having discovered the brook to be in a glorious state, with sticks to dislodge and scamper after down the rushing stream, she was obliged to remove the heavy velvet bonnet, which bobbed over her eyes at inconvenient moments, and hung it scornfully to an alder bough and went her happy way.

At supper-time she appeared hungry and happy. She bethought herself to steal into the bedroom unobserved and hang Sister Sarah's summer dress in its place. It was splashed and muddy, and torn where she had pinned it up.

"I think it looks like a shower," said Mr. McFarland, as they sat down to supper that Saturday night.

It did rain all night long, a searching rain that pattered steadily against the windows after it once began; and it rained half the next day, to everybody's dismay, but Sunday noon it cleared off bright and pleasant.

Sarah McFarland had been trying to forget about bonnets, but it was impossible. While it rained she was partly consoled, but when April began to smile she began to feel sad again. Her father was putting in the horse, and all the family were ready to go, even pale little Eunice, whose cold was better.

Suddenly Sarah came out into the kitchen to tell her mother that the velvet bonnet could nowhere be found.

There was a sudden consternation; they were already afraid of being late, and to everybody's surprise Esther began to cry.

"I was playing queens, and I dressed me up, an' I wore her old bonnet down by the brook, and it got in my eyes, so I taked it off, an' it's there now in a bush, an it'll be all rained on!" Esther mourned aloud and lifted up her voice with her usual unaffected contrition at such moments.

"You dreadful little girl!" said Sarah. "Why, I must stay at home, and who'll speak my piece?" Esther was frightened for once in her life.

"You've got to go, Sarah," said her mother. "Where's that pretty best hood o' Martha's that her aunt sent her ?"

"Take my hat," said Martha, "and I'll wear the hood." But Martha had a piece to speak, too.

It was a terrible emergency. Their father was calling. Martha hastily brought the white hood with its blue border and glittering beads; it had been sent only a week or two before for her birthday. Aunt Sarah was always peculiar about her presents.

For a moment this seemed more than a girl's heart could bear. Then Sarah thought that it was too bad to make everybody else miserable. She had a great tenderness for little Esther, who looked up at her so broken-spirited; the child hadn't meant to do wrong.

"Yes, I'll wear the hood; it's real light and pretty," she said, gallantly, and they were all so happy at that sad moment's end.

Nobody thought for a minute of making Esther stay at home; they all crowded into the big two-seated wagon, but poor Sarah felt like crying all the way to church.

It was really a terrible ordeal to go up the aisle to the speakers' seats that faced the audience, wearing a white winter hood. Just as they were going into the church, which already looked full of people, Mrs. Martin, who seemed to be chief marshal, ran a step or two up the aisle and caught the sisters.

"They're all going to take their hats off, all those that set on the platform," she said, in a loud whisper. "Here, girls, give me yours and I'll deposit 'em in the singin' seats, where they'll be safe."

The McFarland sisters looked at one another with joy. Sarah's smooth young head was never so pretty to look at; her cheeks were like two roses, and the happiness of deliverance shone through her eyes. She spoke her piece beautifully, and John Tanner sang as he had never sung before. In fact, all did their parts well. It was a great Easter day in Walsingham. As for the minister, he talked in quite a wonderful way about Easter itself and the beginnings of a new life in nature and in the heart. The farmers understood him, every word; they had never thought so much before of the planting and growing of a grain of wheat and all it meant. Mr. West was a very uncommon sort of minister.

Even little Esther, fresh from disgrace, meant to put naughtiness behind her and try to be a better girl. But she could not quite understand on Easter Monday morning why Sarah followed her when she was going secretly to the brookside to recover the bonnet. And Sarah seemed so happy and good-natured and not at all offended; and when she saw the green velvet bonnet fairly ruined, she began to laugh heartily.

"I'd like to sail it off down the brook," said Sarah, as soon as she could speak. "But perhaps the old velvet will be good for something."

"Can't you ever wear it again?" asked Esther, with wide eyes.

"No, I hope I can't," said Sarah, frankly, looking down at the little sister. She seemed very happy indeed. "John Tanner said last night when we were walking home that nobody minded about Easter bonnets, anyway. It didn't count the least bit what some people had on - that's just what he said, Essie."

But Esther could not understand any better, and she plodded home beside her sister, still feeling a little guilty. Even their mother, who was usually so careful about everything, began to laugh when she saw the ruins of the bonnet. "I guess it had had its day, darling," she said. And Esther felt then as if the worst were over.

"Did you tell John how you came to

wear the hood to meeting?" asked Mrs. McFarland, and Sarah said,

"Yes, I did, mother." And Esther noticed that her older sister's

cheeks grew very bright, and could not help wondering why.

Illustrations for "A Green Bonnet"

The illustrations are by Clifford Carleton (1867-1946). Born in Brooklyn, he is best remembered for illustrating "Their Wedding Journey" by W. D. Howells and Pembroke by Mary Wilkins Freeman. (Source: Mantle Fielding's Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.)

First page of The Youth's Companion

"All . . . pleas for a new bonnet were unheeded by her

father."

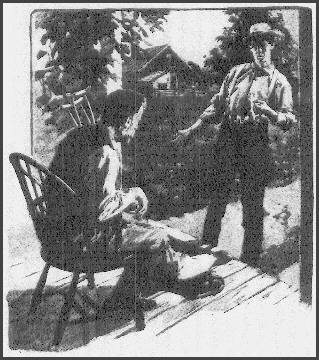

"This once! That's the way forever with this miserable

farm-work!"

Notes

"The Green Bonnet" was published in The

Youth's Companion (75:169-70) in April 1901and was

reprinted by Richard Cary in Uncollected Stories of Sarah

Orne Jewett. This text is from The Youth's Companion.

Easter is the Christian celebration of the

resurrection of Christ after his death on Good Friday.

[ Back ]

Portland: A substantial coastal

town in southern Maine.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College

Main Contents & Search