Uncollected Pieces for Young Readers

Main Contents & Search

THE PARSHLEY CELEBRATION.

Everybody always said that there was no public spirit in the town of Parshley, and nobody ever seemed to think that it might be his own fault. When any great holiday or anniversary came the fact was bewailed from house to house, and from field to field, that it was not likely "they" would do anything; they never did.

Asa Binney's second wife, a pleasant woman whom everybody liked, heard this familiar complaint one Sunday morning in May, just before Decoration day. "Who do you mean by 'they?'" she asked eagerly.

Asa Binney himself and John Foster and three or four others who stood close by, looked confounded by this unexpected question. Nobody answered until Mary Ann Winn, the complainer, broke an awkward silence.

"No, they never do anything to observe Decoration day here," she repeated. "I never did see such a dead-and-alive place as Parshley.

"There ain't [aint] much public spirit in Parshley now; it's very different from what it was when I was a boy," said old Mr. Storer, with a kind of chivalry, as if he wished to uphold Mary Ann. All the listeners looked at Martha Binney with timid disapproval, but the brisk, good-hearted woman held her ground.

"What's the use o' talking about 'they?'" she asked, pleasantly, but with much spirit. "We've all of us, young an' old, got a way of throwin' the blame of such things on nobody in particular. I suppose if we wanted to celebrate we could do it just as well as anybody. We're 'they,' aren't we? We've got to do things ourselves if we want 'em done, in a little place like this."

By this time the minister had come out of church and the rest of the congregation with him. It had been rainy in the early morning and there were but few wagons tied to the fence, but Mrs. Binney was suddenly dismayed by the sight of a reproachful group of listeners.

"What great project is going forward now, Sister Binney?" asked the minister, and Asa came gallantly to his wife's assistance.

"We were speaking of Decoration day, and feeling it ought to be noticed, sir," he answered. "My wife was only saying we'd got to do it ourselves if it were going to be done. She ain't one that ever wants to throw the sermon over into the next pew!"

"All I said was that they never do observe the day; they aint very public-spirited here in Parshley," insisted Mary Ann Winn, suddenly forsaking the attack and putting herself upon the defensive.

"And I asked who 'they' were; it sort of came home to me," said Mrs. Binney. "I was wonderin' if Sister Winn an' I could do anything ourselves."

Then everybody looked at the minister for an answer.

"I shall certainly give such a question my serious thought," said the Rev. Mr. Tasker, after a moment's reflection. "I shall do everything I can to help you," he added, with a smile of unaffected pleasure.

The worst now seemed to be over, and the company quickly separated, not without a sense of happy escape from an unexpected emergency.

There was no village at all in Parshley. It was one of the large townships of northern New England which sometimes get temporary notice through the public press by a statement that they have neither doctor nor lawyer nor public house within their boundaries; being made famous for what they are not and have not, rather than for what they are and have. Such towns are often pleasant and prosperous in their own quietness, and if the truth were known, there is usually a doctor or a lawyer close at hand, just over the border, the next town-line.

As for Parshley, it had a post-office of its own in John Foster's store, near the church, and these two buildings, with the old Foster house and the minister's house, made a small group and neighborhood, which had looked for many years as if it might grow to be a village in the course of time. The rest of the houses were thinly scattered; almost every farm was like an island in a great tract of woodland or rough pasture; you could hardly look out of any window and see another light at night, but this was partly because the country was so nearly level.

John Foster and Asa Binney walked away together after church, leaving their wives to follow. It was a long drive to church from the Binney farm and the younger couple were going to the Fosters' to dinner.

"Mary Ann Winn needn't have been so touchy," said Mrs. Foster, who was stout and already a little out of breath.

"Why, no!" exclaimed Martha Binney, with a pleasant smile. "I didn't mean to blame her, but you never get anything done in a place if you wait for it to do itself."

"What Mary Ann desired to say was that we don't seem to have any leaders nowadays; you've always got to have somebody to take the lead, you know," explained Mrs. Foster.

"Sometimes we've got to take hold and be leaders," answered Mrs. Binney. "I do think such timid persons as Miss Winn hinder others from acting free. They 'most make a credit o' hanging back!"

"There, there!" interrupted her companion, who was always a peacemaker, "when anything gets really started you'll find that Mary Ann'll work day an' night. She may not be one o' your leaders, but she's the best o' the other kind. She may wait for others to plan, but she'll never wait for others to do."

"That's a great point," acknowledged

Mrs. Binney, warmly, as they went in at the gate.

One day early in the week Martha Binney finished her after-dinner work in good season and changed her dress and sat down by the side window to her sewing. The spring was late and cold that year, but at last one could see a bloom of green on the fields. Asa Binney and his son and hired man were all busy out on the land with a piece of heavy, belated plowing. There was a clayey side-hill to be broken up and every time the four-horse team came into sight over the ridge, Martha gave a quick, affectionate look at both horses and men.

The work was going on steadily; she had given the men an extra good dinner and they had gone out to their long afternoon's drudgery in the best of spirits. She had only been married a year or two. Asa Binney's first wife had been an ailing, sad-hearted woman, who always hated farmwork and all that belonged to it, because she was neither strong enough nor able enough for a farmer's wife. Martha, who was large and vigorous and a good manager, took real pleasure in her hard work and good home.

"There, all I ever want is somebody to neighbor with," she said to herself. She had been used to village life before she married, and was a very social person by nature.

The horses' heads came up again over the hill; she watched them strain at their collars with the two young men running beside the half-broken, gay young leaders, and her husband came last, bending hard at his task of following the plow. They all stopped to rest and get their breath at the turn before they went along the slope. Asa was facing toward the house, and his wife smiled at him as if he were near enough to see.

"He's a good man," she said. "That's pretty stiff work for him. By the time Decoration day comes he ought to have a spare day to rest."

As the team disappeared again she slowly threaded her needle and put the big linen spool back on the worn window-sill. Just then, in a lonely moment she looked down the road and saw a figure approaching. Presently she discovered that Mary Ann Winn was coming up the long foot-path that shortened the way to the house across the field.

"Yes, that's Mary Ann, sure 's can be," she said with satisfaction. "I hoped 'twas Mis' [Mis] Foster, but I might have known she couldn't walk so far. There, I'm well prepared as to supper and Mary Ann always has plenty to say."

By this time the guest was near enough to the house to be saluted from the window, and Martha hastened to lay down her sewing and go to open the door.

"Now, you're going to take your things right off and stay and spend the afternoon, and ride home with Asa when he goes to selectmen's meeting," she said heartily, and Mary Ann made but faint protest.

"Lucky I happened to have my knitting in my pocket," she said, when she was comfortably settled in a high-backed rocking-chair close to the window, where Mrs. Binney went on as before, mending an old coat. "The beautiful weather tempted me out. I didn't expect to get half as far as this when I started."

"I'm proper glad you came," answered the hostess. "[']I was just feeling lonesome. There's a time last o' the winter when the men folks don't have much to do outside, and are right underfoot most all the time, but quick as they begin to be off all day, when spring opens, I do begin to miss 'em."

"That was just what Asa's mother used to say. I don't have no men folks the year round," said Mary Ann, in an inexpressive tone. "I 'most [most] forget how 'twould feel now. Mother an' I lived alone 'most fifteen years, and it's seven now that I've had the house all to myself."

Martha Binney turned to look down the field, but the horses and men were not in sight; somehow she could not look away until she saw them all coming.

"I was alone a good while after my mother died, too," she said, softly. "I feel very contented now there's somebody to do for. Yes, I can understand your feelings, Miss Winn."

Mary Ann gave an unconscious sigh. "I expect Asa has told you that I was engaged to be married to his brother David," she said.

"Oh, yes, indeed," said Martha, compassionately, "'twas dreadful hard for you, I'm sure."

"He was a beautiful young man," said Mary Ann. "'Twas a good while before I could bear to think of coming to the house here, but I love to come now. That daguerreotype in the front room that he had taken for his mother same time as mine don't do him any justice. I like mine the best, but they give hardly any idea of his looks. He was very tall and straight, and carried his head high, just the picture of a soldier."

"Asa speaks of him a good deal; he feels his loss yet," said Martha; "'twas all the brother he ever had."

"Asa had to be the one to stay and carry on the farm," said Mary Ann Winn. "You know what a great farm it is, and his father wa'n't what he had been; the boys couldn't both go."

"Yes, 'twas a great disappointment," continued Martha. "Asa was telling me only Sunday night that he believed if he'd been there David wouldn't have died. He don't feel certain he had any sort of care."

"No, I don't, either," said Mary Ann. She spoke in the same unconcerned voice, but the color came and went quickly in her thin cheeks. She turned and looked out of the other window, across the room, and Martha looked, too. They could see two dark spruces on the ridge of land and a faded little flag that fluttered in the spring wind.

"As I was coming along, I couldn't help but think of what you said Sunday, after meeting," Mary Ann said, frankly, after a silence. They both laid their work in their laps and looked eagerly at each other.

"We can't attempt any sort of a procession as they do in big places," she continued. "First place, there wouldn't be anybody to march. The soldiers' widows, and one or two more situated as I be, might all walk together and help out, but I don't know 's 'twould be expedient. And I don't know either 's we want to go to meeting and be preached to; we know all that can be said. I remember once the day came on Sunday and the Walton minister was here to exchange, and he gave an address on war matters in the afternoon, but it worked me up so I couldn't sleep all night. Scenes of the battle-field'll do to interest some o' the young folks. They don't know what war is."

Martha Binney looked up with tears in her kind eyes. "I think some of the women folks that stayed at home gave their lives to the country, much as the men," she said.

"That year altered everything for me," said Mary Ann. "I've done the best I could; 'twas a great comfort to have mother need me as she did. I've got sort of numb and used to things now, but I was dreadful full o' hope an' ambition when I was young. The day I saw David ride off in the wagon with Asa, going to the war was the end of everything for me. He enlisted over to Walton."

"It does seem as if we ought to take some notice of Decoration day," said Martha, presently.

"Have you heard whether they're going to do anything this year?" asked Mary Ann with great eagerness, just as she had asked before, but somehow the words had a different sound to her listener's ears.

"Seems to me as if you an' I might overlook the ground and see if anybody stands in need of help. There aint but a poor few of soldiers' families; we might just go an' see everybody that day and help those that need it and make a kind of friendly visit to the rest. 'Twould be a remembrance," said Martha Binney, with shining eyes. "Asa was telling me Sunday night that he believed old Mis' Paterson on the East Road was having a hard time; he thought she wore a discouraged look, more so than usual. Her son died in hospital and left a young wife and family. They're grown up an' scattered, but he says none of 'em are doing much."

"'Tis a very poor farm an' always was, that Paterson farm," said Mary Ann. "Mis' Paterson's getting to be old; she's got no money to hire and needs help, both outdoors and in. I've been thinking lately I'd go over and make her a little visit and help along what I could, but 'tis quite a ways over there. Why, that's a beautiful idea to go round making calls; anybody can do that!"

"Yes, we'll carry help to those that need it and make a friendly visit to the rest," repeated Martha, as if the plan were already settled to her satisfaction. "I want to make over some clothes for the little Ames boys; their grandma's a soldier's widow. I saw them in very poor array last Sunday."

"Eben Taft's the only veteran left in town now," said Miss Winn, after much reflection. "He's well off, Eben is, and I know he'll take an interest."

"Asa an' I thought we'd speak with him

to-night," said Martha Binney, disclosing her secret plan with

final openness and generosity. And Mary Ann smiled as she had

not smiled before in many a long day.

By twelve o'clock on Saturday there were several small groups of persons scattered about the open space between Foster's store and the church, and when Asa Binney came driving up the road with his new hay-rigging trimmed with green boughs and all his four horses gay with flags in their harness, everybody shouted and cheered.

There was not a wagon tied to the meeting-house posts that did not carry a generous freight, and there were some carefully guarded baskets and bundles on the grass which belonged to the men and women who had come afoot. Asa Binney had provisioned the hay-rigging as if it were going to put to sea on a long cruise, and his wife and Mary Ann Winn had been sewing with double diligence. They had followed the good Bible example of Dorcas, and now sat waiting like two queens in the long cart in two steady old kitchen chairs.

"Take those leaders by the head!" commanded Asa Binney, as his favorite young horses began to prance and rear, and all the boys within hearing rushed to obey.

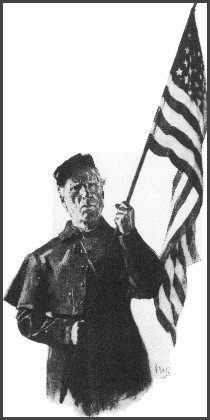

"Oh, look!" cried Mary Ann Winn. "There's Eben Taft coming out of the store to go with us, and he's got on his uniform! I did so hope there would be something that looked like the soldiers!"

"Come along, Eben, you get right in and stand here 'long o' me," said Asa Binney, heartily, and the faded blue overcoat took its place at the front.

Then three or four others followed, men and women; the minister and his wife, and Mrs. Foster, and last of all John himself, who locked the store door after him. He brought a sheaf of flags under one arm, and a large flag on a staff, which he gave to the old soldier.

"'Twas the best I could get," he said. "You ought to be the one to carry it, Eben."

"I've carried the colors before; I guess I can manage it," said Eben Taft, proudly. "There, now we look complete; 'twas the one thing wanting. Start along now, Asa!"

| "I've carried the colors before." |

The great cart moved heavily

along the sandy road. It looked like a triumphal chariot, with

its sober faces of men and women and the new flag flying at the

front. One by one the country wagons all fell into line until

there were ten in the procession, and a good many persons went

afoot as far as old Mrs. Paterson's. On they went slowly past

the green May fields. It was the first day that seemed like

summer, as if summer herself had come to this rustic

celebration.

The tall, blue-coated figure of the veteran looked as soldierly as a whole regiment. This one aging man who had known all the glories, all the horrors of battle, was enough to remind every heart of an unforgotten war, enough to thrill the old with remembrance, and the young with a sudden waking of patriotism. This it was to love and serve your country and to wear her colors; this it was to be honored in a great day. Eben Taft had always come and gone humbly enough in their sight along the Parshley roads, but to-day he was a hero.

"Oh, yes, the folks have heard about our coming," said Martha Binney. "You see 'twas 'most [most] too big a secret to keep in a little place like this. Yes, there's Mis' Paterson standing right in her door, and dear heart, if she aint got a flag, too!"

To have such a procession stop at your door with laden hands, and eager, kind faces, to be made of such consequence when you had long felt poor and dependent; to have it so nobly remembered that you were a soldier's wife or a soldier's mother, when this had only seemed to bring piteous disadvantage and forgetfulness in hard times, cheered more than one heart that lovely day. It seemed as if, having broken the long silence, nobody could do or say enough.

So the few soldiers' graves in the farm burying-grounds were covered with spring flowers, and all the homely gifts from neighbor to neighbor were laid on the altar of patriotism. At every house they left a new, bright flag; at every stopping-place they sang with all their hearts, "My Country, 'tis of Thee," or "Hail Columbia," or some old tune that everybody knew. And if it were a prosperous house instead of a poor one, still they left the flag, and sang, and lingered to speak of those who were gone, but this they did at all the houses that had sent men to war.

"We came to see you to-day for John's sake," Eben Taft said to the old father and mother of one of his comrades. "I can tell you, for I know, that there wa'n't a braver fellow in the field than John, or one that was more neighborlike and kind all through that hard weather in winter camp."

And the old people standing side by side received this simple tribute gravely, but they began to cry when the minister led the singing.

"Sometimes it seemed as if everybody but us had forgot about our John," said the mother.

All the soldiers were counted again that day and remembered, and many a boy and girl wondered at the war-stories that they had never heard before.

It was early evening, the cool, misty air was rising from the fields when the Binneys got home, and the young leaders of the four-horse team were well sobered down. Nobody was needed to take them by the head when they got back to their own green yard. The half-leaved maple boughs which were mixed with pine on the cart trimming were all wilted and dry, but the little flags were as bright as ever.

Mary Ann Winn had come back to supper and to spend the night, for she and Martha had sat sewing and planning together for many days, and happily discovered themselves to be the best of friends. It was going to make a great difference in Mary Ann's life. They got down from the cart, still talking with eager excitement, and Asa handed their chairs after them.

"Just think of this being the first time we ever kept the day in Parshley," said Mary Ann. "How everybody joined right in, and it all went off so ready and easy! Parshley folks are very warm-hearted underneath."

Martha Binney smiled. "Yes, we've had a beautiful day," she said.

"I shouldn't wonder if they did something now to celebrate the Fourth of July," said Mary Ann, hopefully, but she could not quite understand why Mrs. Binney smiled again as she stood on the door-step.

"Perhaps they will!" said Martha, putting out her hand, and then the two good, tired women went into the house together.

NOTES

"The Parshley Celebration" appeared

in The Youth's Companion (73:266-267) on May 25, 1899,

with illustrations by Arthur Jule Goodman, and was reprinted in

Richard Cary's Uncollected Stories of Sarah Orne Jewett.

This text is from Cary. Probable errors have been corrected and

indicated with brackets. Some apparent errors such as the

spellings of "aint" and "most" for "almost" appear in the

original magazine publication, but this text has not been

thoroughly checked against that original. If you see errors or

items in need of annotation, please contact the site manager.

According to the Dictionary

of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists (1978,

1996), Arthur Jule Goodman flourished 1890-1913. Born in

Hartford Connecticut, he studied architecture at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology and worked as an

illustrator before moving to Europe to study and work. His first

published work appeared in Harper's in 1889; later he

worked for the Pall Mall Gazette and other English

magazines.

[ Back ]

Decoration day: Celebrated on

May 30 to honor the dead of the American Civil War by decorating

their graves. Later became Memorial Day, on which all deceased

American veterans are remembered. See also Jewett's story,

"Decoration Day" in A Native of Winby.

[ Back ]

daguerreotype: According

to the Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia, "The

daguerreotype, invented in 1837 by the French artist Louis

Daguerre, was the first practical form of reproduction in

photography. "

[ Back ]

the good Bible example of Dorcas:

See Acts 9:35 for the story of Dorcas.

[ Back ]

"My Country, 'tis of Thee," or "Hail Columbia,": "America" (1831) by Samuel Francis Smith (1808-1895) begins:

My country, 'tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing;

Land where my fathers died,

Land of the pilgrim's pride,

From every mountainside

Let freedom ring.

This American patriotic song is sung to the tune of "God Save the King." Another popular patriotic song, "Hail, Columbia" (1798) by Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842) begins:

Hail, Columbia! happy land!

Hail, ye heroes heaven-born band!

Who fought and bled in Freedom's cause.

According to Bartlett's Familiar Quotations 15th

Edition, it is sung to a tune attributed to Philip Phile, and

was the march at President George Washington's inaugural.

[ Back ]

Fourth of July: This holiday in the

United States celebrates the American Revolution, which began

with the issuing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4,

1776.

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College.