A Winter Drive

It is very hard to find one's way in

winter over a road where one has only driven once in summer. The

landmarks change their appearance so much when the leaves are

gone that, unless the road is straight and certain, and you have

a good sense of locality, you will be puzzled over and over

again. In summer a few small trees and a thicket of bushes at

the side of the road will look like a bit of forest, but in

winter you look through them and over them, and they disappear

almost altogether, they are such thin gray twigs, and take up so

much less room in the world, though you may notice a

well-thatched bird's-nest or some red berries, or a few

fluttering leaves which the wind has failed to blow away. There

is a bare, thin, comfortless aspect of nature which is chilling

to look at either before the snow comes or afterward; you long

for the poor earth to be able to warm herself again by the fire

of the summer sun. The white birches' bark looks out of season,

as if they were still wearing their summer clothes, and the

wretched larches which stand on the edges of the swamps look as

if they had been intended for evergreens, but had been somehow

unlucky, and were in destitute circumstances. It seems as if the

pines and hemlocks ought to show Christian charity to these sad

and freezing relations.

The world looks as if it were at the mercy of the wind and cold in winter, and it would be useless to dream that such a time as spring would follow these apparently hopeless days if we had not history and experience to reassure us. What a sorrowful doom the first winter must have seemed to Adam if he ever took a journey to the northward after he was sent from Paradise! It must have been to him a most solemn death and ending of all vegetable life, yet he might have taken a grim satisfaction in the thought that no more apples could ever get ripe to tempt him or anybody else, and that the mischief-making fruits of the earth were cursed as well as he.

In winter there is, to my mind, a greater beauty in a leafless tree than in the same tree covered with its weight and glory of summer leaves. Then it is one great mass of light and shadow against the landscape or the sky, but in winter the tracery of the bare branches against a white cloud or a clear yellow sunset is a most exquisite thing to see. It is the difference between a fine statue and a well painted picture, and seems a higher art, like that, -- but it is always a puzzle to me why a dead tree in summer should be a painful thing to look at. One instantly tells the difference between a dead twig and a live one close at hand. Such a leafless tree cannot give the pleasure that it did in winter. Yet it looked almost the same in cold weather when it was alive; is it our unreasoning horror of death, or is it that a bit of winter in the midst of summer is like a skeleton at the feast?

A drive in a town in winter should be taken for three reasons: for the convenience of getting from place to place, for the pleasure of motion in the fresh air, or for the satisfaction of driving a horse, but for the real delight of the thing it is necessary to go far out from even the villages across the country. You can see the mountains like great stacks of clear ice all along the horizon, and the smaller hills covered with trees and snow together, nearer at hand, and the great expanse of snow lies north and south, east and west all across the fields. In my own part of the country, which is heavily wooded, the pine forests give the world a black and white look that is very dismal when the sun is not shining; the farmers' houses look lonely, and it seems as if they had crept nearer together since the leaves fell, and they are no longer hidden from each other. The hills look larger, and you can see deeper into the woods as you drive along. Nature brings out so many treasures for us to look at in summer, and adorns the world with such lavishness, that after the frost comes it is like an empty house, in which one misses all the pictures and drapery and the familiar voices.

This was a drive that I liked. It was a sunshiny midwinter day, with a wind that one was glad to fall in with and not try to fight against, and the great white horse ran before it like a boat, the crooked country roads had been just enough smoothed and trodden by the wood teams to make good sleighing. I met now and then a farmer on his way to market with a load of fire-wood piled high and square on his sled, and the oxen were frosted, and pushed at the yoke and bumped together awkwardly, as if they could not walk evenly with their crooked knees. There was a bundle of corn-stalks on top the load, and usually the driver's blue mittens were on the sled stakes, with the thumbs out at right angles, as if some spirit of the woodlands were using them to show the protesting hands he lifted at the irreverence of men. It was many years before I ever felt very sorry when woods were cut down. There were some acute griefs at the loss of a few familiar trees, but now I have a heart-ache at the sight of a fresh clearing, and I follow as sadly along the road behind a great pine log as if I were its next of kin and chief mourner at its funeral. There is a great difference between being a live tree that holds its head so high in the air that it can watch the country for miles around, -- that has sheltered a thousand birds and families of squirrels and little wild creatures, - that has beaten all the storms it ever fought with; such a difference between all this and being a pile of boards!

I believe that there are few persons who cannot remember some trees which are as much connected with their own lives as people are. When they stand beside them there is at once a feeling of very great affection. It seems as if the tree remembered what we remember; it is something more than the fact of its having been associated with our past. Almost everybody is very fond of at least one tree. Morris's appeal to the woodman struck a responsive chord in many an otherwise unsentimental heart, -- but happy is the man who has a large acquaintance and who makes friends with a new tree now and then as he goes on through the world. There was an old doctrine called Hylozoism, which appeals to my far from Pagan sympathies, the theory of the soul of the world, of a life residing in nature, and that all matter lives; the doctrine that life and matter are inseparable. Trees are to most people as inanimate and unconscious as rocks, but it seems to me that there is a good deal to say about the strongly marked individual characters, not only of the conspicuous trees that have been civilized and are identified with a home, or a familiar bit of landscape or an event in history, but of those that are crowded together in forests. There is a strange likeness to the characteristics of human beings among these, there is the same proportion of ignorant rabble of poor creatures who are struggling for life in more ways than one, and of self-respecting, well-to-do, dignified citizens. It is not wholly a question of soil and of location any more than it is with us. Some trees have a natural vitality and bravery which makes them push their roots into the ground and their branches toward the sky, and although they started to grow on a rock or on the sand, where we should be sure that a tree would have a hard struggle to keep alive, and would be stunted and dwarfed at any rate, yet they grow tall and strong, and in their wealth of usefulness they are like some of the world's great men who rose from poverty to kingliness. How easy it is to carry out the likeness. The great tree is a protection to a thousand lesser interests, a central force which keeps in motion and urges on a thousand activities.

It is common to praise a man more who has risen from obscurity to greatness than one who had money and friends at the start, but there is after all little difference in the amount of personal exertion that must be brought to bear. If a man or a tree has it in him to grow, who can say what will hinder him. Many a tree looks starved and thin, and is good for nothing, that was planted in good soil, and the grandest pines may have struggled among the rocks until they find soil enough to feed them, and when they are fully grown the ledges that were in the way of their roots only serve to hold them fast and strengthen them against any chance of overthrow. There is something in the constitution of character; it is vigorous and will conquer, or it is weak and anything will defeat it. I believe that it is more than a likeness between the physical natures, there is something deeper than that. We are hardly willing yet to say that the higher animals are morally responsible, but it is impossible for one who has been a great deal among trees to resist the instinctive certainty that they have thought and purpose, that they deliberately anticipate the future, or that they show traits of character which one is forced to call good and evil. How low down in the scale of existence we may find the first glimmer of self-consciousness nobody can tell, but it is as easy to be certain of it in the higher orders of vegetable life as in the lower orders of animals. Man was the latest comer into this world, and he is just beginning to get acquainted with his neighbors, that is the truth of it. It is curious to read the old stories of the hamadryads and see the ways in which the life of trees has been dimly recognized. They mean more than has been supposed, but the trees' own individuality was ignored, and an imaginary race of creatures invented, and supposed to live in them -- these spirits of the trees accounted for things that could not otherwise he explained, but they were too much like people, the true nature and life of a tree could never be exactly personified.

Most trees like most people are

collected into great neighborhoods, and one only knows them in

companies, as one looks at a strange town when on a journey and

thinks of it only as a town without remembering that it is made

up of old and young lives, each with its own interests and

influence. Perhaps as you go by, you notice a few faces in the

street or at the railway station, and so, when a country road is

at the edge of some woods you notice the woods, and perhaps say

to yourself that there is a fine walnut-tree or an oak, but

there are no two trees that look alike or are alike, any more

than there are two persons exactly similar in shape or nature.

It is a curious thing to see the difference of race so strongly

marked -- an oak among white pines is like an Englishman among

the Japanese, and wholly a foreigner in such society. There is a

nobility among trees as well as among men, not fancied by poets

but real and unaffected. One likes to

see such a grand family of oaks as that at

Waverley, and is delighted at the thought of their long

companionship; and what is more imposing than a row of elms

standing shoulder to shoulder before a fine old house? They have

watched the people come out for the first time, and for the last

time, they have known the family they have sheltered. There

seems to be often a curious linking of the two lives, which

makes a tree fade and die when the man or woman dies with whom

it has been associated; such stories are common in every

village, -- there is a superstition that the withering of a tree

near a house is the sign of impending disaster -- many persons

believe that there is something more than coincidence and chance

about it, and it may be at least that these signs, and others

that come true, will be proved some day to be veritable

warnings, to break the force of a blow that otherwise would be

too sudden and severe.

Five or six miles from the village I left the road that leads down to the sea and turned off toward the hill called Agamenticus. From some high land which has to be crossed first there is a fine view of the northern country with the procession of mountains, of which Mt. Washington is captain, ranged in marching order on the horizon. Saddleback and its comrades in Deerfield and Strafford brought up the rear, and they were all pale blue in the afternoon light. The nearer hills looked wind-swept and forlorn and the lowlands desolate, and the world was like a great garden that was spoiled and blackened by frost. The snow glistened and the wind blew it off the edges of the great drifts as if it were the spray of those frozen waves. The smoke was coming out of the kitchen chimneys of the farm-houses, and I saw faces quickly appear at the windows as I went by. All the women hurry when they hear sleigh-bells or the sound of passer-by in those lonely neighborhoods, and it is difficult to tell whether you give most pleasure by being a friend who will tell the news or do an errand along the road, or by being a stranger who drives an unknown horse. Then you are made the subject of reflection and inquiry, and for perhaps a day or two you are like an exciting chapter that ends abruptly in a serial novel.

Once over the hills there came in sight a long narrow pond which lies at the foot of Agamenticus; and as I passed the saw-mill at the lower end by the bridge I saw a well-worn sled track on the ice, and I had too strong a temptation to follow it to be resisted. The pond seemed like a river, the distance was not great across from shore to shore, and the banks were high and irregular and covered in most places with pines. I had heard that there was a good deal of logging going on in the region, and it was the best possible chance to get into a swampy tract of country which is inaccessible in summer, and which I have always wished to explore. For perhaps three quarters of a mile I went up the pond, often between the rows of logs which were lying on the ice waiting for the time when they would melt their way into the water and float down to be sawed. I found a cross track which led in the direction I wished to take, and once in the woods there was no wind, and the air was still and clear and sweet with the cold and resinous odor of the trees. The wood-road was not very smooth and the horse chose his own way slowly while I looked around to see what could be seen. The woods were almost still, only the blue jays cried once or twice, and sometimes a lump of snow would fall from the bough of a tall pine down through the branches of the lower trees. There were a great many rabbit tracks, those odd clover-leaf marks, deep in the light snow which had fallen the night before, and there were partridge tracks around some bushes to which few dried berries were still clinging, but the creatures themselves were nowhere to be seen. It must be a dreadful thing to be lost in the woods in winter! The cold itself soon puts an end to one, luckily; but to be hungry in such a place, and cold too, is most miserable. It makes one shudder, the thought of a lost man hurrying through the forest at night-fall, the shadows startling him and chasing him, the trees standing in his way and looking always the same as if he were walking in a treadmill, the hemlocks holding out handfuls of snow at the end of their branches as if they offered it mockingly for food.

The people who live in the region of the Agamenticus woods have a good deal of superstition about them; they say it is easy to get lost there, but they are very vague in what they say of the dangers that are to be feared. It may be like an unreasoning fear of the dark, but sometimes there is a suggestion that the bears may not all be dead, and almost every year there is a story told of a wild-cat that has been seen, of uncommon size; and as for a supernatural population, I think that passes for an unquestioned fact. I have often heard people say that there are parts of the woods where they would not dare to go alone, and where nobody has ever been, but I could never succeed in locating them. The swamps at the foot of the mountain are traversed in winter pretty thoroughly and the first and second, and sometimes even the third, growth of pines have been cut off from all that district, so the land has all been walked over at one time and another -- since there are few trees of the older generation left in all that part of the town. I dare say there is a little fear of the hill itself; perhaps a relic of the old belief that the gods had their abodes in mountains. So high a hill as Agamenticus could not fail to be respected in this (for the most part) low-lying country, and in spite of its barely seven hundred feet of height it is as prominent a landmark for fifteen or twenty miles inland as it is for sailors who are coming toward the coast, or for the fishermen who go in and out daily from the neighboring shores. I have often been asked about the legend of an uncertain St. Aspenquid, -- whose funeral ceremonies on this mountain are represented as having been most imposing, but I never could trace this legend beyond a story in one of the county newspapers, and I have never heard any tradition among the people that bears the least likeness to it.

I caught now and then a glimpse of the top of Agamenticus as I drove through the woods that bright winter day, and I wished it were possible for any one, not a practiced mountain climber, to scramble up through the drifts and over the icy ledges. I should like to see the winter landscape, the wide-spread country, the New Hampshire mountains, and the sea; for one can follow the coast line from Gloucester on Cape Ann to Portland with one's unaided eyesight; so well planted is this hill which might be called the watchtower on the western gates of Maine.

In the woods there was the usual number of stray-away trees to be seen, and they appealed to my sympathy as much as ever. It is not pleasant to see an elm warped and twisted with its efforts to get to the light, and to hold its head above the white pines that are growing in a herd around it and seem to grudge it its rights and its living. If you cannot be just like us, they seem to say, more's the pity for you! You should grow as we do and be like us. If your nature is not the same as ours you ought to make it so. These trees make one think of people who have had to grow in loneliness; who have been hindered and crowded and mistaken and suspected by their neighbors, and have suffered terribly for the sin of being themselves and following their own natures. Yet I have often seen trees who seem to be hermits and recluses of their own accord -- not forced absentees from their families. Apple-trees, in spite of their association with the conventional life of orchards and the neighborhood of buildings, do not seem unhappy at the sunshiny edge of a piece of woods, especially if they are near a road. Perhaps they like living alone, as many people do -- they are glad to be freed from the restraints of society, and are very well off where they are; though a lonely domesticated tree would seem, naturally, to be most forlorn, an elm among pines or an oak among hemlocks seems to draw attention to its sufferings far more eagerly. An apple-tree seems willing to make itself at home anywhere but it is sure to get amusingly untidy and lawless, as if it needed to be preached to as well as pruned. There are many trees, however, that always gravitate into each other's society and live in peace and harmony with each other -- well ordered neighborhoods where there is good chance for everybody to get his living.

I have remembered a great many times an old lilac tree that I once saw in bloom by a deserted farm-house. It was in so secluded a place on a disused road that it could not be sure it was not the last of its race. The earth was washed away from its roots, and it was growing discouraged; it was like a sick man's face at a window. I do not believe that it will bloom many more springs. But there is another solitary tree which is a great delight to me, and I go to pay it an afternoon visit every now and then, far away from the road across some fields and pastures. It is an ancient pitch-pine, and it grows beside a spring, and has acres of room to lord it over. It thinks everything of itself, and although it is an untidy housekeeper, and flings its dry twigs and sticky cones all around the short grass underneath, I have a great affection for it. I like pitch-pines better than any trees in the world at any rate, and this is the dearest of its race. I sit down in the shade of it and the brook makes a good deal of noise as [i intending it ] starts out from the spring* under the bank, and there always is a wind blowing overhead among the stiff green branches. The old tree is very wise, it sees that much of the world's business is great foolishness, and yet when I have been a fool myself and wander away out of doors to think it over, I always find a more cheerful atmosphere, and a more sensible aspect to my folly, under the shadow of this friend of mine. I think it is likely to live until the new houses of the town creep over to it, past Butler's Hill, and the march of improvement reaches it and dooms it to be cut down because somebody thinks it would not look well in his yard, or because a street would have to deviate two or three feet from a straight line. However, there is no need to grow angry yet, and the tree is not likely to die a natural death for at least a hundred years to come, unless the lightning strikes it, -- that fierce enemy of the great elms and pines that stand in high places.

There is something very sad about a dying tree. I think in the progress of civilization there will, by and by, arise a need for the profession of tree doctors, who will be quick at a diagnosis in cases of yellow branches and apt surgeons at setting broken limbs, and particularly successful in making the declining years of old trees as comfortable as possible. These physicians will not only wage war against the apple-tree borers and the plums' black knots, but a farmer will be taught to go through his woods now and then to see that nothing is the matter, just as he inspects his cattle, and he will call the doctor for the elms that have not leaved out as they ought, and the oaks that are dying at the top, and the maples that warp and split their bark, and the orchard trees that fail to ripen any fruit. He will be told to drain this bit of ground and turn the channel of a brook through another -- time fails me to tell the resources of a profession yet in its infancy! It is a very short-sighted person who looks at the wholesale slaughter of the American forests without dismay, especially in the Eastern States. The fast drying springs and brooks in the farming districts of certain parts of New England show that mischief has already been done, and the clearing of woodlands is going to be regulated by law, I believe, at some not far distant period. There ought to be tree laws as well as game laws.

I thought of this as I drove on, deeper and deeper into the woods, and could hear more and more plainly the noise of the lumberman at work; first the ringing hack, hack, of the axes against the live, hard wood; and then I caught the sound of voices as the teamsters shouted to each other and to their oxen. There seemed to be a great deal going on, as if there were a crowd of men and a great excitement, but when I could see the open space between the tree there proved to be in all five or six placid-looking farmers with one team drawn by two oxen and a shaggy, unwilling old white horse for leader. This was just ready to start, being loaded with logs to be carried out to the pond, and it was lucky that we had not met it, for the snow was deep and soft outside the narrow track.

The snow was trampled and covered with brush-wood and fallen boughs, the woods looked torn to pieces as if there had been a battle. "This is the way it used to look down in Virginia in war times," said John, the Captain of Horse, who was driving me: "I tell you, you had to dodge when a big shell burst among the pine-trees; there would be a crashing and a cracking among the old fellows!" We stopped and spoke to the teamster, and one or two of the choppers who were near by came to the side of the sleigh, and we asked and told the news. I spoke of a fire that had been in the village the night before, but they had already found out all about it. It is unaccountable how fast a bit of news will travel in the country, it is a proof of the frequency of communication between farming people, -- you need only let it get a few minutes' start of you in the morning and it will beat you by many miles on a day's drive. It is not that a man starts out ahead of you with a faster horse and tells everybody he sees along the road, but this invisible telegraph has sidelines, and people who live at the end of long lanes and on lonely cross roads are as well posted as those on the main thoroughfares.

It would be too slow work following the team, so we were directed back to the pond by another succession of paths. I noticed the bits of bright color against the dull green of the woods and the whiteness of the snow. The choppers wore red shirts and sometimes blue overalls, and there was a much-worn brown fur cap, with long ear-pieces that flapped a good deal as the energetic wearer nodded his head in explaining our way to us, and disputing the length of different cart-paths with one of his companions. I watched a man creep carefully, like a great insect, along the trunk of a fallen tree, and begin to lop off its branches. It seemed to me that the noise of the lumbermen in the woods must be very annoying to the trees and wake them from their quiet winter sleep, like a racket in a house at night. The scattered trees that were left standing had a shocked and fearful look, as if some fatal epidemic had slain their neighbors. Just at the edge of the clearing we crossed a little brook, busy under the ice and snow, and coming out to scurry and splash around a lichened rock with great unconcern, as if it were a child playing with its toys in the next room to a funeral.

There were a great many pines notched with an axe to show that they were to be cut; about a hundred and fifty pines in all, the owner told us he was going to get out that season, and they had so far been able to fell them without doing much damage to those they meant to leave standing. Some of the stumps were unusually broad ones. They last many years, and so the tree leaves its own monument when it dies. The inscription on many of the older stumps in those woods might be Lost at sea, as it is on the stones of a sea-port burying-ground, for great quantities of ship timber have gone from the Agamenticus woods to the ship-yards at Portsmouth, and the navy yard across the river.

On my way back to the pond and the road I found a place I remembered crossing in my childhood, a marshy bit of ground and a small pond in the heart of the woods. It looked exactly as it had that early winter day so long ago, and I remembered that I had seen witch-hazel in bloom there for the first time, and had been filled with astonishment at the sight of flowers in the snow. There used to be a farm-house, now destroyed, at the side of the mountain to which this was a short road in winter when the ground was frozen. I looked around for the witch-hazel, but I was too late for it, it was out of bloom and, alas, many flowers beside! else I might have thought it was only yesterday I was there before, that bit of the world had been so unforgotten and unchanged by time. I had wondered for years where that little pond could be. I had begun to think I needed a crooked twig of the uncanny witch-hazel itself to lead me back to it.

The wind seemed to be making a louder noise than usual when I came out from the stillness of the woods to the open country. The horse was glad to be on a better road and struck out at a brave trot, and, indeed, it was time to hurry, for it was on the edge of the winter twilight and that had been the last load of logs to be sent that day from the clearing. I looked up again and again at the mountain, and I noticed a white place among the trees where there were cleared fields, and remembered a story that always interested me, that there was once a small farm there where an old Scotchman lived alone, many years ago. No one knew from whence he came, and there was no clew to his family or friends, so after his death the property that he left fell to the State. There is something very strange about such hidden-away lives, and one cannot help thinking that there are always people who have watched sadly for such stray-aways to come home, even if they are fugitives from justice or banished with good cause.

On the main road, again, I met a dismal-looking little clam-man driving back to the sea. He and his horse both looked as if they would freeze to death on the way. I heard some clams slide and clash together in the box on his sled as we turned out for each other, but it was nearly empty and I had seen it full in the morning, so I suppose he was contented. We said good-day, and he went on again. He was a little bit of a man, and his eyes looked like a fish's eyes from under the edge of a great, rough fur cap. "He's very well off," said John. "I know where he lives at the Gunket." So, after all, I pitied the horse the most, for he never would have been so shaggy if he lived in a barn that the wind off the sea did not blow through every day, from one end to the other.

The last sight I had of the mountain

the top of it was bright where the last flicker of the clear,

yellow sunset touched it, but in the low-lands where I was the

light was out, and the wind had gone down with the sun, and the

air was still and sharp. The long, cold winter night had begun.

The lamps were lit and the fires were blazing in all the houses

as I hurried home.

Notes

"A Winter Drive" first appeared in Country

By-Ways, from which this text is taken.

[ Back ]

Adam ... sent from Paradise:

Adam and Eve are expelled from their first home in the Garden of

Eden when they disobey their creator by eating of forbidden

fruit (See Genesis 3).

[ Back ]

Morris's appeal to the woodman:

Woodman, spare that tree! / Touch not a single bough! / In youth

it sheltered me, / And, I'll protect it now. This is the opening

of George Pope Morris's (1802-1864) poem, "Woodman Spare That

Tree (1830).

[ Back ]

Hylozoism: as Jewett's context

suggests, this is a doctrine that all matter has life.

[ Back

]

hamadryads: wood nymphs.

[ Back ]

One likes to see such a grand family of oaks

as

that at Waverley: Possibly an allusion to Sir Walter

Scott's Waverley (1814). Edward Waverley, the

protagonist, spends much of his childhood at the family estate,

Waverley-Honor. When in love, he writes a poem, "Mirkwood Mere"

(see Chapter 5), which mentions oak trees on the estate.

[ Back ]

Agamenticus ... Mt. Washington ... Saddleback

...

in Deerfield ... Strafford: Agamenticus is the highest

point in the region of South Berwick, Maine, home of the Jewett

family. Mt. Washington and Saddleback are in the White Mountains

of New Hampshire, as are the towns of Deerfield and Strafford.

[ Back ]

St. Aspenquid: Also

spelled "Aspinquid," this is, as Jewett suspects, a legendary

Indian, though during Jewett's lifetime, he was associated with

the historical Passaconaway, whom Jewett mentions in "The Old

Town of Berwick" and The Tory Lover. Passaconaway

was the leader of the Pennacook Confederacy of Abenaki tribes

and bands that occupied New Hampshire, southern Maine, and

northeastern Massachusetts during the 17th Century. Known

for his political and military skill and for his peaceable

attitude toward the European settlers, Passaconaway inspired

legends of his prowess as a magician as well as a leader.

It is not surprising, therefore, that he would inspire a sort of

folk legend such as that of St. Aspinquid.

Legend says that St. Aspinquid is buried at

the top of Mt. Agamenticus, where an elaborate funeral was held

for him, with hundreds in attendance and extravagant

slaughtering of animals and incredible feasting. According

to historian J.

Dennis

Robinson, the Aspinquid Masonic lodge maintains a

sign at the mountain top recounting this legend. That

plaque reads:

ST. ASPINQUID

Died 1682

Aged 94

He was converted the Christian faith and was thereafter known as St. Aspinquid.

When he died, Indians came from hundreds of miles away to pay tribute to his memory

And it's alleged that 6,723 wild animals were sacrificed here to celebrate his funeral on the mountain.

He was buried here on Mt. Agamenticus, and [as] was the Indian custom, his grave was covered with stones.

Robinson also demonstrates that the story of St.

Aspinquid almost certainly is a white invention.

Robinson has traced the invention of the

legend to two documents. The first may be the article to

which Jewett refers in this sketch:

| Saint Aspenquid Written by John Albee Vintage News This mountain, situated in the northeasterly part of

York, Me., is a noted landmark for mariners, and is

the first height seen by them from the sea on the

coast northward and eastward of Portsmouth. Here the

United States coast survey have erected a cairn or

pile of rocks on which to place a temporary

observatory from which to make astronomical

observations. St. Aspinquid is the name of a Jesuit

saint or hero who was held in profound veneration by

the aboriginal inhabitants throughout Maine, who are

known to have been Indians, both in the religious and

warlike distinction. His sanctity was well established

among them; yet, who he was, or why he deserves these

honors is not known. Indian tradition, transmitted

from age to age, and from tribe to tribe, informs us

this patron saint of theirs lived and died on Mount

Agamenticus in 1682, and that his funeral was

celebrated by the Indians with a sacrifice of six

thousand five hundred and eleven wild animals. |

Robinson thanks Richard Winslow for discovering this article. The second document is an 1884 poem, also by John Albee, that elaborates this story into the legend that Jewett refers to, entitled "Saint Aspenquid." The poem opens:

The Indian hero, sorcerer and saint,

Known in the land as Passaconaway,

And after called the good Saint Aspenquid,

Returning, travel worn and spent with age

From vain attempt to reconcile his race

With ours, sent messengers throughout the East

To summon all the blood-bound tribes to him;

For that upon the ancient meeting-place,

The sacred mountain Agamenticus,

When next the moon should show a new-bent bow,

He there would celebrate his funeral feast

With sacrifices due and farewell talk.

Earlier sources have not been located, though the poem echoes a famous "farewell" oration of 1660, said to have been delivered by Passaconaway to his people, notably in this part:

And here once more on Agamenticus,

My old ancestral powow's sacred seat,

That saw the waters burn and trees to dance,

And winter's withered leaves grow green again,

And in dead serpent's skin the living coil,

While they themselves would change themselves to flame;

And where not less did I myself did I conjure

The mighty magic of my fathers' rites

Against my foe, -- yet all without effect;

The spirits also flee where white men come.

In C. E. Potter's version of the oration in his History

of

Manchester (1856), Passaconaway says:

The English came, they seized our lands; I sat me down at

Pennacook. They followed upon my footsteps; I made war upon

them, but they fought with fire and thunder; my young men were

swept down before me, when no one was near them. I tried sorcery

against them, but they still increased and prevailed over me and

mine, and I gave place to them and retired to my beautiful

island of Natticook. I that can make the dry leaf turn green and

live again -- I that can take the rattlesnake in my palm as I

would a worm, without harm -- who have had communion with the

Great Spirit dreaming and awake -- am powerless before the Pale

Faces (60).

Karen Oakes quotes William Dean Howells's

description of the statue of St. Aspinquid at the entrance of

St. Aspinquid Park in York Beach, ME: "His statue,

colossal in sheet-lead, and painted the copper color of his

race, offers any heathen comer the choice between a Bible in one

of his hands and a tomahawk in the other...." (" 'Colossal

in Sheet-Lead': The Native American and Piscataqua-Region

Writers," in A Noble and Dignified Stream, edited by S.

L. Giffen and K. D. Murphy. York: Old York Historical

Society, 1992), pp. 166-7.

[ Back ]

spring: Wendy Pirsig of the Old Berwick Historical

Society believes the spring to which Jewett refers is the origin

of an unnamed local creek. Her photos show the spring and the

pines along this creek beyond Butler's Hill in South Berwick,

ME.

Spring at the origin of the creek

The unnamed creek -- with today's pines

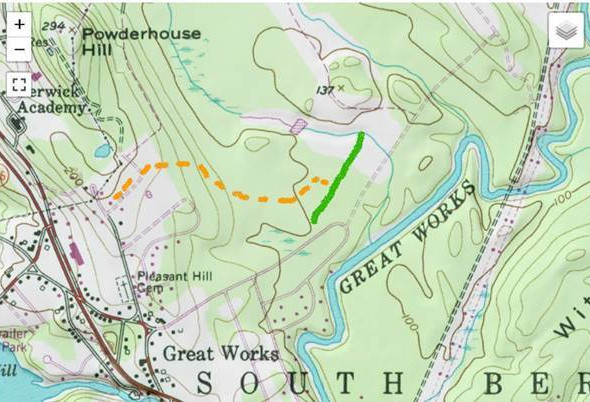

Pirsig provides this map to indicate the creek's location in relation to Jewett's home.

Jewett's home is in the upper left corner of this map, to the left of the +. Powderhouse Hill is the current name for Butler's Hill. The broken gold line indicates one possible walking route from Highway 236 to the creek, shown in green. By this route, it would be roughly 1.5 miles from Jewett's house to the creek. The spring is at the left end of the green line; the creek flows into another creek at the right end of the green line. This area remains undeveloped, accessible only on foot.

John, the Captain of Horse:

John Tucker was a long-time Jewett family employee.

[ Back ]

witch-hazel: a fall-blooming shrub

with thin-petalled yellow flowers, the bark of which is used in

a soothing but astringent lotion. (Research Ted Eden).

[ Back ]

crooked twig: a divining rod,

often made of witch-hazel.

[ Back ]

Gunket: This may refer to the

Negunket River in York County, Maine, between Wells and

York..

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, Coe College.