Main Contents & Search

| A Native of

Winby Harper's Magazine Text |

Marty & Jim in St.

Augustine - Extended Notes The Diverse People of "Jim's Little Woman" |

Sarah Orne Jewett

I.

There was laughter in the lanes of St. Augustine when Jim returned from a Northern voyage with a Northern wife. He had sailed on the schooner Dawn of Day, one hundred and ninety-two tons burden, with a full cargo of yellow pine and conch-shells. Not that the conch-shells were mentioned in the bill of lading, any more than five handsome tortoise-shells that were securely lashed to the beams in the captain's cabin. These were a private venture of the captain's and Jim's. The Dawn of Day did a great deal of trading with the islands, and it was only when the season of Northern tourists was over that her owners found it more profitable to charter her in the lumber business. It was too hot for bringing any more bananas from Jamaica, the last were half spoiled in the hold; and those Northerners who came excitedly after corals and sprouted cocoanuts and Jamaica baskets, who would gladly pay thirty cents apiece for the best of the conch-shells, brought primarily by way of ballast, -- those enthusiastic, money-squandering Northerners had all flown homeward at the first hints of unmistakable summer heat, and market was over for that spring.

St. Augustine is a city of bright sunshine and of cool sea winds, a different place from the steaming-hot, listless-aired Southern ports which Jim knew well, -- Kingston and Nassau and the rest. He had sailed between the islands and St. Augustine and Savannah, and made trading voyages round into the Gulf, ever since he ran away to sea on an ancient brigantine bound for Havana, in his early youth. Jim's grandfather was a Northern man by birth, a New-Englander, who had married a Minorcan woman, and settled down in St. Augustine to spend the rest of his days. Their old coquina house near the sea-wall faced one of the narrow lanes that ran up from the water, but it had a wide window in the seaward end, and here Jim remembered that the intemperate old sailor sat and watched the harbor, and criticised the rigging of vessels, and defended his pet orange-tree from the ravages of boys. His wife died long before he did, and the daughter, Jim's mother, was married, and her husband ran away and never was heard from, and Jim himself was ten years old when he walked at the head of the funeral procession, dimly imagining that the old man had gone up North, and that he was to live again there among the scenes of his youth. There were a few old shipmates walking two by two, who had known the captain in his active life, but they held no definite views about his permanent location in high latitudes. Still, there was a long procession and a handsome funeral; and after a few years Jim's mother died too, a friendly, sad-faced little creature whom everybody lamented. Jim came into port one day after a long absence, expecting to be kissed and cried over and coaxed to church and mended up, to find the old coquina house locked and empty. He shipped again gloomily; there was nothing for him to do ashore; and that year the boys took all the oranges, and people said that the old captain's ghost lived in the house. The bishop stopped Jim one day on the plaza, and told him that he must come to church sometimes for his mother's sake: she was a good little woman, and had said many a prayer for her boy. Did Jim ever say a prayer for himself? It was a hard life, going to sea, and he must not let it be too hard for his soul. "Marry you a good wife soon," said the kind bishop. "Be a good man in your own town; you will be tired of roving and will want a home. God have pity on you, my boy!"

Jim took off his hat reverently, and his frank, bold eyes met the bishop's sad, kind eyes, and fell. He had never really thought what a shocking sort of fellow he was until that moment. He had grown used to his mother's crying, but it was two or three years now since she died. The fellows on board ship were afraid of him when he was surly, and owned him for king when he was pleased to turn life into a joke. He was Northern and Southern by turns, this Southern-born young sailor. He could talk in Yankee fashion like his grandfather until the crew shook the ship's timbers with their laughter. But in all his roving sea-life he had never been to the coast of Maine until this story begins.

The Dawn of Day was a slow sailer, and what wind she had was only a light south-westerly breeze. Every other day was a dead calm, and so they drifted up the Northern coast as if the Gulf Stream alone impelled them, making for the island of Mount Desert with their yellow pine for house-finishing; and somewhere near Boothbay Harbor their provisions got low, and the drinking-water was too bad altogether, and there was nothing else left to drink, so the captain put in for supplies. They could not get up to the inner harbor next the town, but came to anchor near a little village when the wind fell at sundown. There were some houses in sight, dotted along the shore, and a long, low building at the water's edge, close to the little bay. Jim and the captain and another man pulled ashore to see what could be done about the water-casks, and the old water-tank, which had been rusty, was leaky and good for nothing when they first put to sea.

Jim went ashore, and presently put his head into a window of the long, low building; there were a dozen young people there, and two or three men, with heaps of lobster shells and long rows of shining cans. It was a lobster-canning establishment, and work was going on after hours. Somebody screamed when Jim's shaggy head and broad shoulders shut out the little daylight that was left, and a bevy of girls laughed provokingly; but one of them -- Jim thought she was a child until she came quite close to him -- asked what he wanted, and listened with intelligent patience until he had quite explained his errand. It proved easy to get somebody to solder up the water-tank, and in spite of the other girls this little red-haired, white-faced creature caught her hat from a nail by the door, and went off with Jim to find the solderer, who lived a quarter of a mile down the shore.

Jim thought of the old bishop many times as he walked decently along by the little woman's side. He thought of his mother, too, and how she used to cry over him; he never pitied her for it before. He remembered his cross old grandfather and those stories about the North, and by a strange turn of memory he mentally cursed the boys who came to steal the old man's oranges, there in the garden of his own empty little coquina house. What a thing to have a good little warm-hearted wife of his own! Jim felt as if he had been set on fire; as if something hindered him from ever feeling like himself again; as if he must forever belong to this little bit of a woman, who almost ran, trying to keep up with his great rolling sea strides along the road. She had a clear, pleasant little voice, and kept looking up at him, asking now and then something about the voyage as if she were used to voyages, and seemed pleased with his gruff, shy answers. He heaved a great sigh when they came to the solderer's door.

The solderer came out and walked back with them, saying that his tools were all at the factory. He told Jim that there was the best cold spring on the coast convenient to the schooner, just beyond the factory, and a good grocery store near by. There was no reason for going up to Boothbay Harbor and losing all that time in the morning, and Jim's heart grew light at the news. He sent the solderer off to the schooner, and stayed ashore himself. The captain had already heard about the grocery, and had gone there. The grumbling member of the crew, who was left in the boat, looked back with heart-felt astonishment to see Jim sit down on a piece of ship timber beside that strange little woman, and begin to talk with her as if they were old friends. It was a clear June evening, the sky was pale yellow in the west, and on the high land above the shore a small jangling bell rang in its white steeple. A salt breath of sea wind ruffled the smooth water. The lights went out in the canning factory and twinkled with bright reflections from the schooner. The solderer finished his work on board, and was put ashore close to his own house; as for the captain, he remained with some new-made friends at the grocery.

They wondered on the deck of the Dawn of Day what had come over Jim; they laughed and joked, and thought that he might have found one of his relations about whom he had told the Yankee stories. As long as there was any light to see, there he sat, an erect, great fellow, with the timid-looking woman like a child by his side. The captain came off late, and in a state unbefitting the laws of Maine, and Jim came with him, sober, pleasant, but holding his head in that high, proud way which forbade any craven soul from putting an unwelcome question.

The next morning, when the wind rose, the Dawn of Day put out to sea again. Somebody besides Jim may have noticed that a white handkerchief fluttered at one of the canning-factory windows, but nobody knew that it meant so much to Jim as this: the little woman was going to marry him, and promised by that signal to come to Mount Desert to meet him. They had no more time for courtship; it was now or never with the quick-tempered fellow. Little Martha did not dare to promise until she had thought it over that night; but she was a lonely orphan, and had no ties to keep her there. Jim had told her about his home and his orange-tree in the South, and when morning came she had thought it over and said yes, and then even cried a little to see the old schooner go out to sea. She said yes because she loved him; because she had never thought that anybody would fall in love with her, she was so small and queer, and not like the rest of the girls. Jim had certainly waved his handkerchief in reply; and as Marty remembered that, she felt in her pocket for a queer smooth shell to make herself sure that she was not dreaming. Jim had carried this shell in his pocket for good luck, as his strange old seafaring grandfather had done before him, and by it he plighted his faith and troth. Before they sighted Monhegan, running far out to catch the wind, he told the skipper that he was going to be married, and expected to carry his wife down to St. Augustine in the Dawn of Day. The skipper swore roundly, but Jim was the ablest man aboard, and had been shipped that voyage as first mate. They were short-handed, and he was in Jim's power in many ways. There was a wedding, before the week was out, at a minister's house, and Jim gave the minister's wife a pretty basket of shells besides what Marty considered to be a generous wedding fee. He had bought a suit of ready-made clothes before he went to the cousin's house where the little woman had promised to wait for him. Marty did not explain to this cousin that she had only seen her lover once in the twilight. She wondered if people would think Jim rough and strange, that was all; but Jim for once was in possession of small savings, and when he came, so tall and dark, shaven and shorn and dressed like other people, she fell to crying with joy and excitement, and had much difficulty in explaining to her lover that it was nothing but happiness and love that had brought such tears. And after the yellow pine was on the wharf, and the conch-shells sold at unexpected rates to a dealer in curiosities at Bar Harbor, who got news of them, and after much dickering gave but a meagre price for the tortoises also, the Dawn of Day set forth again southward with dried fish and flour from Portland, where, with his share of the conch-shell gains, Jim had given his wife such a pleasuring as he thought a lord who had an earldom at his back might give his fair lady.

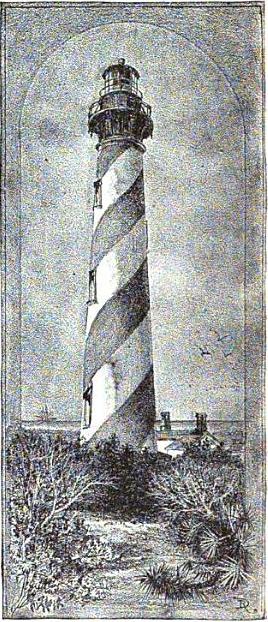

When the crew first caught sight of Jim's small, red-headed, and pale-faced wife, the discrepancy in the size of the happy couple was more than could be silently borne. Jim always spoke of her as his little woman, and Jim's little woman she was to the world in general. She was as proud-spirited as he. She seldom scolded, but she could grow pale in the face and keep silence if things went wrong. The schooner was a different place on that return voyage. They had the captain's cabin, and she made it look pretty with her girlish arts. She mended everybody's clothes, and took care of the schooner's boy when he was sick with a fever turn, -- a hard-faced little chap, who had run about from ship to ship, just as Jim had; and though the wind failed them most of the time going south, they were all sorry when they reached St. Augustine bar. The last Sunday night of all, Jim's little woman got out her Moody and Sankey song-book for the last time, and sang every tune she knew in her sweet, old-fashioned voice. She was rough in her way sometimes, but the crew of the Dawn of Day kept to the level of its best manners in her hearing all the time she was on board. As they lay out beyond the bar, waiting for enough water to get in, she strained her eyes to see her future home. There was the queer striped light-house, with its corkscrew pattern of black and white, and far beyond were the tall, slender towers of a town that looked beautiful against the sunset, and a long, low shore, white with sand and green here and there with a new greenness which she believed to be orange-trees. She may have had a pang of homesickness for the high ledgy pasture shores at home, but nobody ever guessed it. If ever anybody in this world married for love, it was Jim's little woman.

II.

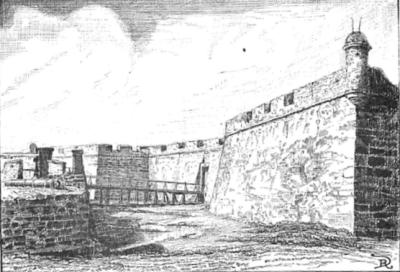

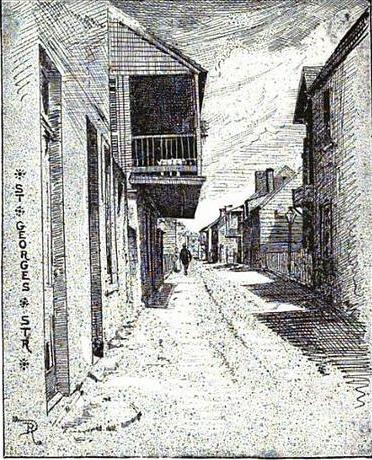

It was not long before the dismal little, boarded-up, spidery coquina house was as clean as a whistle, with new glass windows, and fresh whitewash inside and yellow wash outside; with curtains and rugs and calico cushions, and a shining cooking-stove, on which such meals were concocted as Jim never dreamed of having for his own. The little woman had a small inheritance of housekeeping goods, which had been packed into the schooner's hold; luckily these had been in charge of the Northeast Harbor cousin; as Jim said, they had to get married, for everything came right and there was nothing else to do. He seemed as happy as the day was long, and for once was glad to be ashore. They went together to do their marketing, and he showed her the gray old fort one afternoon and the great hotels with the towers. In narrow St. George Street, under the high flower-lined balconies, everybody seemed to know Jim, and they had to spend much time in doing a trifling errand. Go into St. George Street when she would, the narrow thoroughfare was filled with people, and dark-eyed men and women leaned from the balconies and talked to passers-by in a strange lingo which Jim seemed to know. People laughed a good deal as they passed, and the little woman feared that they might think that she was queer-looking. She hated to be so little when Jim himself was so big; but somehow the laughter all stopped after one day, when a man with an evil face said something in a mocking voice, and Jim, blazing with wrath, caught him by the waist and threw him over the fence into a garden.

"They laugh to think o' me getting so small a wife," said Jim frankly one day, in one of his best moods. "One o' the boys thought I'd raised me a fambly while we was gone, and said I'd done well for a little gal, but where was the old lady. I promised I'd bring him round to supper some night, too; he's a good fellow," added Jim. "We'll have some o' your clam fritters, and near about stuff him to death."

The summer days flew by, and to everybody's surprise Jim lived the life of a sober man. He went to work on one of the new harbor jetties at his wife's recommendation, and did good service. He gave Marty his pay, and was amused and astonished to see how far she made it go. With plenty of good food, he seemed to have lost his craving for drink in great measure; and they had two boarders, steady men and Jim's mates, for there was plenty of room; and the little woman was endlessly busy and happy. Jim had his dark Spanish days with a black scowl, and Marty had her own hot tempers, that came, as she said, of the color of her hair. Like other people, they had their great and small trials and troubles, but these always ended in Marty's stealing into her husband's lap as he sat by the window in his grandfather's old chair. The months went by, and winter came, and spring and their baby came, and then they were happier than ever. Jim, for his mother's sake, carried him to the old bishop to be christened, and all the neighbors flocked in afterward and were feasted. But there was no mistake about it, Jim drank more than was good for him that day in his pride and joy, and had an out and out spree while the baby's mother was helpless in bed; it was the first great worry and sorrow of their married life. The neighbors came and sat with Marty and told her all about him; and she got well as fast as she could, and went out, pale and weak, after him, and found Jim in a horrid den and brought him home. But he was sorry, and said it was all the other fellows' fault, and a fellow must have his fling. The little woman sighed, and cried too when there was nobody to see her. She had never believed, though she had had warnings enough, that there was any need of being anxious about Jim. Men were different from women. Yet anybody so strong and masterful ought surely to master himself. But things grew worse and worse; and at last, when the old schooner, with a rougher-looking crew than usual, came into the harbor, the baby's father drank with them all one night, and shipped with them next morning, and sailed away, in spite of tears and coaxing, on a four months' voyage. Marty had only three cents in her thrifty little purse at the time. It was a purse that her mate at the canning factory gave her the Christmas before she was married. All the simple, fearless old life came up before her as she looked at it. The giver had cried when they parted, and had written once or twice, but the last letter had been long unanswered. Marty had lost all her heart now about writing; she must wait until Jim was at home and steady again. Alas, the months went by, and it seemed as if that time would never come.

Jim came home at last, drunk and scolding, and when he went away again with the schooner it would have been a relief to be rid of him, if it were not for the worry. He did not look so strong and well as he used. Under the tropic skies his habits were murdering him slowly. The only comfort Marty could take in him was when he lay asleep, with the black hair curling about his smooth white forehead, and that pleasant boyish look coming out on his face instead of the Spanish scowl. The little woman lost her patience at last, and began to wear a scowl too. She was a peppery little body, and sometimes Jim felt himself aggrieved and called her sharp names in foreign tongues. He had a way of bringing his cronies home to supper when she was tired, and ordering her about contemptuously before the low-faced men. At last, one night, they made such a racket that a group of idle negroes clustered about the house, laughing and jeering at the company within. Marty's Northern fury rose like a winter gale; she was vexed by the taunts of a woman who lived up the lane, who used to come out and sit on her high blue balcony and spy all their goings on, and call the baby poor child so that his mother could hear. Jim's little woman drove the ribald company out of doors that night, and they quailed, drunk as they were, before her angry eyes. They chased the negroes in their turn, and went off shouting and swearing down the bayside. They tried to walk on the sea-wall, and one man fell over and was too drunk to find his way ashore, and lay down on the wet, shelly mud. The tide came up and covered Joe Black, and that was the last of him, which was not without its comfort, for Jim stayed humbly at home, and tried to make his wife think better of him, for days together. He had won an out and out bad name in the last year. Nobody would give him a good job ashore now, so that he had to go to sea. He was apt to lead his companions astray, and go off on a frolic with too many followers. Yet everybody liked Jim, and greeted him warmly when he came ashore; and he could walk as proudly as ever through the town when he had had just drink enough to make him think well of himself and everybody else. He dodged round many a corner to avoid meeting the bishop, that good, gray-haired man with the kind, straightforward eyes.

Marty made a good bit of money in the season. She liked to work, and was always ready to do anything there was to do, -- scrubbing or washing and ironing or sewing, -- and she came to be known in the town for her quickness and power of work. While Jim was away she always got on well and saved something; but when he came in from his voyages things went from bad to worse; and after a while there was news of another baby, and the first one was cross and masterful; and the woman up the lane, in her rickety blue balcony, did nothing but spy discomforts with her mocking eyes.

Jim was more like himself that last week before he went to sea than for a long time before. He seemed sorry to go, and kept astonishingly sober all the last few days, and picked the oranges and planted their little vegetable garden without being asked, and made Marty a new bench for her tubs that she had only complained of needing once or twice. He worked at loading the schooner down at the sawmill, and came home early in the evening, and Marty began to believe she had at last teased him and shamed him into being decent. She even thought of writing to her friend in Boothbay after two years' silence, she had such new hopes about being happy and prosperous again. She talked to Jim about that night when they first saw each other, and Jim was not displeased when she got the lucky shell out of a safe hiding-place and showed him that she had kept it. They looked each other in the face as they seldom did now, and each knew that the other thought the shell had brought little luck of late. Jim sat down by the window and pulled Marty into his lap, and she began to cry the minute her head was on his shoulder. Life had been so hard. What had come over Jim?

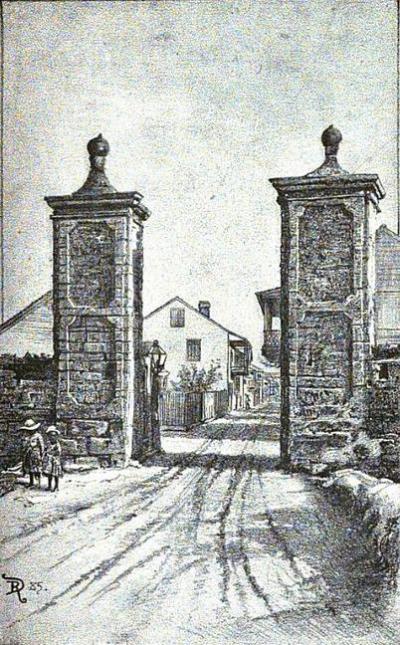

"That old bishop o' my mother's," faltered Jim. "He's been givin' it to me; he catched me out by the old gates, and he says, 'Jim, you're goin' to break your little woman's heart.' Was that so, Marty?"

Marty said nothing; she only nodded her head against his shoulder and cried like a child. She could feel his warm shoulder through his coat, and in a minute he asked her again, "Was that so, Marty?" And Marty, for answer, only cried a little less. It was night, and Jim was going away in the morning. The crickets were chirping in the garden. Somebody went along the sea-wall singing, and Jim and his little woman sat there by the window.

"The devil gets me," said Jim at last, in a sober-minded Northern way that he had sometimes. "There's an awful wild streak in me. I ain't goin' to have you cry like mother always done. I'm goin' to settle down an' git a steady job ashore, after this one v'y'ge to the islands. I'm goin' to fetch ye home the handsomest basketful of shells that ever you see, an' then I'm done with shipping, I am so."

"'T ain't me only; 'tis them poor little babies," said Marty, in a tired, hopeful little voice. She had done crying now. She felt somehow as if the reward for all her patience and misery was coming.

"I wouldn't go off an' leave ye now, as things be with ye," said Jim, "but you see we need the money; an' then I've shipped, and the old man's got my word. I'm stout to work aboard ship, an' he knows it, the cap'n does. The old bishop he warned me against the cap'n; he said if 't wa'n't for him I'd be master o' a better vessel myself. He works me hard an' keeps me under. I do believe the bishop's right about him, and I'd kept clear from drink often if 't wa'n't for the old man."

"You've kep' you under," said honest Marty. "Nobody ain't master over you when it comes to that. You've got to set your mind right against drink an' the cap'n, Jim."

"It's so cursed hot in them islands," Jim explained. "You get spent, and have to work right through everything; but I give you my honest word I'll bring you home my pay this trip."

At which promise the little woman gave a pleased sigh, and moved her head as if for sheer comfort. She tried to think whether there was anything else she could have done to the poor clothes in his battered sea-chest; then she fell asleep. When she waked in the morning, Jim had laid her on the bed like a child, and spread an old shawl over her, and had gone. At high tide in the early morning the schooner Dawn of Day had come up from the sawmill wharf with a tug, and sent a boat ashore for Jim. Marty had never missed him as she did that morning; she had never felt so sure of his loving her, and had waked thinking to find herself still in his arms as she had fallen asleep. There stood the empty chair by the window; and through the window, over beyond the marshes, she could see the gray sails of the schooner standing out to sea. Oh, Jim! Jim! and their little child was crying in the crib, like a hungry bird in its nest -- the poor little fellow! -- and calling his father with pleading confidence. Jim liked the brave little lad. When he was sober, he always dressed up on Sundays and took little Jim and his mother for a walk. Sometimes they went to the old Spanish burying-ground, and Jim used to put the baby on his grandfather's great tombstone, built strong over his grave like a little house, and pick the moss from the epitaph with his great sea jack-knife. His mother had paid for the tomb. She was laid at one side of it, but Jim had never built any tomb for her. He meant to do it, some time, and Marty always picked some flowers and green sprigs and laid them on the grave with its bits of crumbling coquina at the head and foot.

In spite of a pain at her heart, and a

foreboding that Jim would never come back from his unwilling

voyage, the little woman went up the lane boldly that late

morning after he sailed; she no longer feared the mocking smile

and salutation of the neighbor in the balcony. She went to her

work cheerfully, and sang over it one of her Moody and Sankey

hymns. She made a pleasure for the other women who were washing

too, with her song and her cheerful face. She was such a little

woman that she had a box to stand on while she washed, but there

never was such a brisk little creature for work.

III.

Somehow everything prospered in the next two months until the new baby came. Some young women hired all her spare rooms, and paid well for their lodging, besides being compassionate and ready to give a little lift with the housework when they had the time. Marty had never laid by so much money before, and often spoke with pride of her handsome husband to the lodgers, who had never seen him: they were girls from the North, and one of them had once worked in a canning factory. One day Marty wrote to her own old friend, and asked her to come down by the steamer to Savannah, and then the rest of the way by rail, to make her a long visit. There was plenty of hotel work in the town; her lodgers themselves got good wages on George Street.

Jim was not skilled with his pen; he never wrote to her when he went away, but ever since they were married Marty always had a dream one of the nights while he was gone, in which she saw the schooner's white sails against a blue sky, and Jim himself walking the deck to and fro, holding his head high, as he did when he was pleased. She always saw the Dawn of Day coming safe into harbor in this dream; but one day she thought with a sudden chill that for this voyage the good omen was lacking. Jim had taken the lucky shell along; at any rate, she could not find it after he went away; that was a little thing, to be sure, but it gave some comfort until one morning, in shaking and brushing the old chair by the seaward window, out dropped the smooth white shell. The luck had stayed with her instead of going with poor Jim, and the time was drawing near for his return. The new baby was a dear little girl; she knew that Jim wanted a girl baby, and now, with the girl baby in her arms, she began her weary watch for white sails beyond the marshes.

The winter days dawned with blue skies and white clouds sailing over; the town began to fill with strangers. As she got strong enough there was plenty of work waiting for her. The two babies were a great deal too large and heavy for their little mother to tend; they seemed to take after Jim in size, and to grow apace, and Marty took the proud step of hiring help. There was a quiet little colored girl, an efficient midget of a creature, who had minded babies for a white woman in Baya Lane, and was not without sage experience. Marty had bought a perambulator the year before from a woman at one of the boarding-houses, who did not care to carry it North. When she left the hired help in charge that first morning, and hurried away to her own work, the neighbor of the blue balcony stood in her lower doorway and bade her a polite good-morning. But Jim's little woman's eyes glittered with strange light as she hurried on in the shadow of the high wall, where the orange boughs hung over, and beyond these, great branches laden with golden clusters of ripening loquats. She had not looked out of the seaward window, as she always liked to do before she left the house, and she was sorry, but there was no time to go back.

The old city of St. Augustine had never been more picturesque and full of color than it was that morning. Its narrow thoroughfares, with the wide, overhanging upper balconies that shaded them, were busy and gay. Strangers strolled along, stopping in groups before the open fronts of the fruit shops, or were detained by eager venders of flowers and orange-wood walking-sticks. There were shining shop windows full of photographs and trinkets of pink shell-work and palmetto. There were pink feather fans, and birds in cages, and strange shapes and colors of flowers and fruits, and stuffed alligators. The narrow street was full of laughter and the sound of voices. Lumbering carriages clattered along the palmetto pavement, and boys and men rode by on quick, wild little horses as if for dear life, and to the frequent peril of persons on foot. Sometimes these small dun or cream-colored marsh tackeys needed only a cropped mane to prove their suspected descent from the little steeds of the Northmen, or their cousinship to those of the Greek friezes; they were, indeed, a part of the picturesqueness of the city.

The high gray towers of the beautiful Ponce de Leon Hotel, with their pointed red roofs, were crowned with ornaments like the berries of the chinaberry-trees, and Marty looked up at them as she walked along, and at the trees themselves, hung with delicate green leaves like a veil. Spring seemed to come into the middle of summer in that country; it was the middle of February, but the season was very early. There was a mocking-bird trying its voice here and there in the gardens. The wind-tattered bananas, like wrecked windmills, were putting out fresh green leaves among their ragged ones. There were roses and oranges in bloom, and the country carts were bringing in new vegetables from beyond the old city gates; green lettuces and baskets of pease and strawberries, and trails of golden jasmine were everywhere about the gray town. Down at the foot of the narrow lanes the bay looked smooth and blue, and white sails flitted by as you stood and looked. The great bell of the old cathedral had struck twelve, and as Marty entered the plaza, busy little soul that she was and in a hurry as usual, she stopped, full of a never outgrown Northern wonder at the foreign sights and sounds, -- the tall palmettoes; the riders with their clinking spurs; the gay strangers; the three Sisters of St. Joseph, in their quaint garb of black and white, who came soberly from their parish school close by. Jim's little woman looked more childlike than ever. She always wore a short dress about her work, and her short crop of red curly hair stood out about her pale face under the round palmetto hat. She had been thinking of Jim, and of her afternoon's affairs, and of a strange little old negro woman who had been looking out of a doorway on George Street, as she passed. It seemed to Marty as if this old withered creature could see ghosts in the street instead of the live passers-by. She never looked at anybody who passed, but sometimes she stood there for an hour looking down the street and mumbling strange words to herself. Jim's little woman was not without her own superstitions; she had been very miserable of late about Jim, and especially since she found his lucky shell. If she could only see him coming home in her dream; she had always dreamed of him before!

Suddenly she became aware that all the little black boys were running through the streets like ants, with single bananas, or limp, over-ripe bunches of a dozen; and she turned quickly, running a few steps in her eagerness to see the bay. Why had she not looked that way before? There at the pier were the tall masts and the black and green hull of the Dawn of Day. She had come in that morning. Marty felt dizzy, and had to lean for a minute against the old cathedral doorway. There was a drone of music inside; she heard it and lost it; then it came again as her faintness passed, and she ran like a child down the street. Her hat blew off and she caught it with one hand, but did not stop to put it on again. The long pier was black with people down at the end next the schooner, and they were swarming up over the side and from the deck. There were red and white parasols from the hotel in the middle of the crowd, and a general hurry and excitement. Everybody but Marty seemed to have known hours before that the schooner was in. Perhaps she ought to go home first; Jim might be there. Now she could see the pretty Jamaica baskets heaped on the top of the cabin, and the shining colors of shells, and green plumes of sprouted cocoanuts for planting, and the great white branches and heads of coral; she could smell the ripe fruit in the hold, and catch sight of some of the crew. At last she was on the gangway, and somebody on deck swore a great oath under his breath. "Boys," he said, in a loud whisper, "here's Jim's little woman!" and two or three of them dropped quickly between decks and down into the hold rather than face her. When she came on board, there was nobody to be seen but the hard-faced cabin-boy whom she had taken care of in a fever as they came down from Boothbay. He had been driving a brisk trade with some ladies down in the captain's cabin.

"Where's Jim gone?" said Marty, looking at him fiercely with her suspicious gray eyes.

"You'd better go ask the cap'n," said the boy. He was two years older than when she first knew him, but he looked much the same, only a little harder. Then he remembered how good Marty had been to him, and that the "old man" was in a horrid temper. He took hold of Marty's thin, freckled, hard-worked little hand, and got her away aft into the shadow and behind the schooner's large boat. "Look here," he faltered, "I'm awful sorry, Marty; it's too bad, but -- Jim's dead."

Jim's wife looked the young fellow straight in the face, as if she were thinking about something else, and had not heard him.

"Here, sit right down on this box," said the boy. But Marty would not sit down; she had a dull sense that she must not stay any longer, and that the sun was hot, and that she could not walk home along the sea-wall alone.

"I'll go home with you," said the boy, giving her a little push; but she took hold of his hand and did not move.

"Say it over again what you said," she insisted, looking more and more strange; her short red hair was blowing in the wind all about her face, and her eyes had faded and faded until they looked almost white.

"Jim's dead," said the hard-looking boy, who thought he should cry himself, and wished that he were out of such a piece of business. The people who had come to chaffer for shells began to look at them and to whisper. "He's dead. He -- well, he was as steady as a gig 'most all the time we was laying off o' Kingston, and the ol' man couldn't master him to go an' drink by night; and Jim he wouldn't let me go ashore; told me he'd 'bout kill me; an' I sassed him up an' down for bossin', and he never hit me a clip back nor nothin': he was queer this voyage. I never see him drunk but once, -- when we first put into Nassau, -- and then he was a-cryin' afterwards; and into Kingston he got dizzy turns, and was took sick and laid in his bunk while we was unloadin'. 'Twas blazin' hot. You never see it so hot; an' the ol' man told how 'twas his drinkin' the water that gave him a fever; an' when he went off his head, the old man got the hospit'l folks, an' they lugged him ashore a-ravin'; an' he was just breathin' his last the day we sailed. We see his funeral as we come out o' harbor; they was goin' out buryin' of him right off. I ain't seen it myself, but Jim Peet was the last ashore, an' he asked if 'twas our Jim, an' they said 'twas. They'd sent word in the mornin' he was 'bout gone, and we might 's well sail 'f we was ready."

"Jim Peet saw his funeril?" gasped the little woman. "He felt sure 'twas Jim?"

"Yes 'm. You come home 'long o' me; folks is lookin'," said the boy. "Come, now; I'll tell you some more goin' along."

Marty came with him through the crowd.

She held her hat in her hand, and she went feeling her way, as

if she were blind, down the gangway plank. When they reached the

shore and had gone a short distance, she turned, and told the

lad that he need not come any farther; if he would bring his

clothes over before the schooner sailed, she would mend them all

up nice for him. Then she crept slowly along Bay Street

bareheaded; the sun on the water at the right blinded her a

little. Sometimes she stopped and leaned against the fence or a

house front, and so at last got home. It was midday, there was

not a soul in the house, and Jim was dead.

That night she dreamed of a blue

sky, and white sails, and Jim, with his head up, walking the

deck, as he came into harbor.

IV.

All the townsfolk who lived by the water-side and up and down the lanes, and many of the strangers at the hotels, heard of poor Marty's trouble. Her poorest neighbors were the first to send a little purse that they had spared out of their small savings and earnings; then by and by some of the hotel people and those who were well to do in the town made her presents of money and of clothes for the children; and even the spying neighbor of the balcony brought a cake, and some figs, all she had on her tree, the night the news was known, and put them on the table, and was going away without a word, but Marty ran after her and kissed her, for the poor soul's husband had been lost at sea, and so they could weep together. But after the dream everybody said that Marty was hurt in her mind by the shock. She could not cry for her own loss when she was told over and over about her neighbor's man; she only said to the people who came that they were very kind, and she was seeing trouble, but she was sure that Jim would come back; she knew it by her dream. They must wait and see. She could not force them to take their money back, and when she grew too tired and unstrung to plead about it any longer, she put it together in a little box, and hid it on a high cupboard shelf in the chimney. There was a wonderful light of hope in her face in these days; she kept the little black girl to tend the two babies, and kept on with her own work. Everybody said that she was not quite right in the brain. She was often pointed out to strangers in that spring season, a quaint figure, so small, so wan, and battling against the world for her secret certainty and hope.

Never a man's footstep came by the house at night that she did not rouse and start with her heart beating wildly; but one, two, three months went by, and still she was alone. Once she went across the bay to the lighthouse island, -- babies, baby-carriage, the small hired help, and all, -- and took the railway that leads down to the south beach. It was a holiday, and she hoped that from this southern point she might look far seaward, and catch sight of the returning sails of the old schooner. She would not listen to her own warnings that Jim had plenty of ways of getting home besides waiting for the Dawn of Day. Those who saw the little company strike out across the sand to the beach laughed at the sight. The hired help pushed the empty perambulator with all the strength she could muster through the deep white sand, and over the huge green, serpent-like vines that wound among the low dunes. Marty carried the baby and tugged the little boy by the other hand, and sat down at the edge of the beach all alone, while the children played in the sand or were pushed to and fro. She strained her eyes after sails, but only a bark was in sight to the northward beyond the bar, and a brigantine was beating southward, and far beyond that was a schooner going steadily north, and it was not the Dawn of Day. All the time Jim's little woman kept saying to herself: "I had the dream; I had the dream. Jim will come home." But as this miserable holiday ended, and they left the great sand desert and the roar of the sea behind them, she felt a new dread make her heart heavier than ever it had been before; perhaps even the dream was mocking her, and he was dead indeed.

Then Marty had need of comfort. She believed that as long as she kept faith in her omen it would come true, and yet her faith slowly ebbed in spite of everything. It was a cruel test, and she could not work as she used; she felt the summer heat as she never had before. All her old associations with the cool Northern sea-coast began to call her to come home. She wondered if it would not do to go North for a while and wait for Jim there. The old friend had written that next winter she would come down for a visit, and somehow Marty longed to get home for a while, and then they could come South together; but at last she felt too tired and weak, and gave up the thought. If it were not for the children, she could go to Jamaica and find out all about Jim. She had sent him more than one letter to Kingston, but no answer came. Perhaps she would wait now until next summer, and then go North with Lizzie.

In midsummer the streets are often empty at midday, and the old city seems deserted. Marty sometimes took the children and sat with them in the plaza, where it was shady. Often in the spring they all wandered up the white pavement of the street by the great hotel to see the gay Spanish flags, and to hear the band play in the gardens of the Ponce de Leon; but the band did not play as it used. Marty used to tell the eldest of the children that when his father came home he would take him sailing in the bay, and the little fellow got a touching fashion of asking every morning if his father were coming that day. It was a sad summer, -- a sad summer. Marty knew that her neighbors thought her a little crazed; at last she wondered if they were not right. She began to be homesick, and at last she had to give up work altogether. She hated the glare of the sun and the gay laughter of the black people; when she heard the sunset gun from the barracks it startled her terribly. She almost doubted sometimes whether she had really dreamed the dream.

One afternoon when the cars stopped at the St. Augustine station, Marty was sitting in the old chair by the seaward window, looking out and thinking of her sorrow. There was a vine about the window that flickered a pretty shadow over the floor in the morning, and it was dancing and waving in the light breeze that blows like a long, soft breath, and then stops at sundown. She saw nothing in the bay but a few small pleasure-boats, and there was nothing beyond the bar. News had come some time before that the Dawn of Day had gone north again with yellow pine, and the few other schooners that came now and then to the port were away on the sea, nobody knew where. They came in as if they dropped out of the sky, as far as Marty was concerned. She thought about Jim as she sat there; how good he was before he sailed that last time, and had really tried to keep his promise on board ship, according to the cabin-boy's story. Somehow Jim was like the moon to her at first; his Spanish blood and the Church gave an unknown side to his character that was always turned away; but another side shone fair through his Northern traits, and of late she had understood him as she never had before. She used to be too smart-spoken and too quick with him; she saw it all now; a quick man ought to have a wife with head enough to keep her own temper for his sake. "I couldn't help being born red-headed," thought Marty with a wistful smile, and then she was dreaming and dozing, and fell fast asleep.

The train had stopped in the station, and among the strangers who got out was a very dark young man, with broad shoulders, and of uncommon height. He was smartly dressed in a sort of uniform, and looked about him with a familiar smile as he strolled among the idlers on the platform. Suddenly somebody caught him by the hand, with a shout, and there was an eager crowd about him in a minute. "Jim! Here's dead Jim!" cried some one, with a shrill laugh, and there was a great excitement.

"No," said Jim, "I ain't dead. What's the matter with you all? I've been up North with the best yacht you ever see; first we went cruisin' in the Gulf an' over to Martinique. Why, my wife know'd I was goin'. I had a fellow write her from Kingston, an' not to expect me till I come. I give him a quarter to do it."

"She thinks you're dead. No; other folks says so, an' she won't. Word come by the schooner that you was dead in hospit'l, of a Jamaica fever," somebody explained in the racket and chatter.

"They always was a pack o' fools on that leaky old Dawn o' Day," said Jim contemptuously, looking down the steep, well-clothed precipice of himself to the platform. "I don't sail with those kind o' horse-marines any more."

Then he thought of Marty with sudden intensity. "She never had got his letter!" He shouldered his great valise and strode away; there was something queer about his behavior; nobody could keep up with his long steps and his quick runs, and away he went toward home.

Jim's steps grew softer and slower as he went down the narrow lane; he saw the little house, and its door wide open. The woman in the blue balcony saw him, and gave a little scream, as if he were a ghost. The minute his foot touched the deep-worn coquina step, Marty in her sleep heard it and opened her eyes. She had dreamed again at last of the blue sky and white sails; she opened her eyes to see him standing there, with his head up, in the door. Jim not dead! not dead! but Jim looking sober, and dressed like a gentleman, come home at last!

That evening they walked up Bay Street to King Street, and round the plaza, and home again through George Street, making a royal progress, and being stopped by everybody. They told the story over and over of its having been another sailor from a schooner, poor fellow! who had died in Kingston that day, alone in hospital. Jim himself had gone down to the gates of death and turned back. There was a yacht in harbor that had lost a hand, and the owner saw handsome Jim on the pier, looking pale and unfriended, and took a liking to him, and found how well he knew the Gulf and the islands, so they struck a bargain at once. They had cruised far south and then north again, and Jim only had leave to come home for a few days to bring away his little woman and the children, because he was to keep with the yacht, and spend the summer cruising in Northern waters. Marty had always been wishing to make a visit up in Maine, where she came from. Jim fingered his bright buttons and held his head higher than ever, as if he had been told that she felt proud to show him to her friends. He looked down at little Marty affectionately; it was very queer about that dream and other people's saying he was dead. He must buy her a famous new rig before they started to go North; she looked worn out and shabby. It seemed all a miracle to Marty; but her dream was her dream, and she felt as tall as Jim himself as she remembered it. As they went home at sunset, they met the bishop, who stopped before them and looked down at the little woman, and then up at Jim.

"So you're doing well now, my boy?" he said good humoredly, to the great, smiling fellow. "Ah, Jim, many's the prayer your pious mother said for you, and I myself not a few. Come to Mass and be a Christian man for the sake of her. God bless you, my children!" and the good man went his wise and kindly way, not knowing all their story either, but knowing well and compassionately the sorrows and temptations of poor humanity.

It seemed to Marty as if she had had time to grow old since the night Jim went away and left her sleeping, but the long misery was quickly fading out of her mind, now that he was safe at home again. In a few days more, the old coquina house was carefully shut and locked for the summer, and they gave the key to the woman of the blue balcony. The morning that they started northward, Marty caught a glimpse of the Dawn of Day coming in through the mist over the harbor bar. She wisely said nothing to Jim; she thought with apprehension of the captain's usual revelry the night he came into port. She took a last look at the tall light-house, and remembered how it had companioned her with its clear ray through many a dark and anxious night. Then she thought joyfully how soon she should see the far-away spark on Monhegan, and the bright light of Seguin, and presently the towers of St. Augustine were left out of sight behind the level country and the Southern pines.

NOTES

"Jim's Little Woman" first appeared

in Harper's Magazine

(82:100-110) in December 1890, and was collected in A Native

of Winby (1893). This text is from the 1893 edition.

In Sarah Orne Jewett, Paula Blanchard

says that in January, 1888, Annie Fields contracted pneumonia

and nearly died. Her doctor recommending warm weather,

Fields decided to go to St. Augustine, Florida, with Jewett to

help her. Rita Gollin in Annie Adams Fields: Woman of

Letters reports that the two returned for an extended stay

in spring 1890, this time for Jewett's health.

[ Back ]

Kingston and Nassau: Kingston is

the capital of Jamaica. Nassau is the capital of the Bahamas.

[ Back ]

brigantine: a large sailing

ship with a fairly simple set of sails and, hence, requiring a

small crew.

[ Back ]

Havana: Capital of the Caribbean

island of Cuba.

[ Back ]

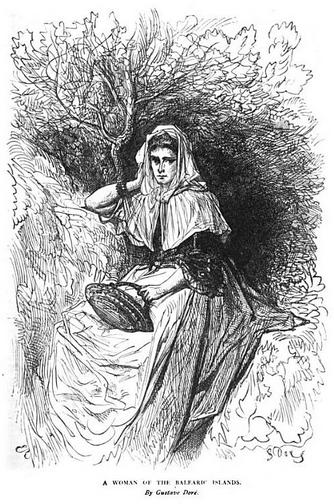

Minorcan woman: Minorca is one of

Spain's Balearic Islands, located in the western Mediterranean

Sea. Jim's "Spanish blood" comes from his

Minorcan-American grandmother. Minorcans occupy an

important position in the history of St. Augustine. Jewett

likely was familiar with The

Standard

Guide,

St. Augustine by Charles Bingham Reynolds, which was

reprinted regularly in the late 19th century and which provides

a summary account of how Minorcans came to a significant element

of the population of St. Augustine. Reynolds writes:

[ Back ]In 1769, during the British occupation, a colony of Minorcan and Majorcans were brought from the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea to New Smyrna, on the Indian River, south of St Augustine. Deceived by Turnbull, the proprietor of the plantation, and subjected to gross privation and cruelty, the Minorcans at length appealed to the authorities of St. Augustine, were promised protection, deserted from New Smyrna in a body, came to St Augustine, were defended against the claims of Turnbull, received an allotment of land in the town, built palmetto-thatched cottages and remained here after the English emigrated.

A Woman of the Balearic Islands

by Gustave Doré

C. B. Reynolds, p. 19.

coquina house: "Coquina is a form

of limestone composed of broken fragments of fossil debris. Most

fragments are about the size of gravel particles (greater than 2

mm/0.08 in) and are usually shell material -- coquina is derived

from the Spanish word meaning "cockle" or "shellfish" -- that

has been abraded during transport by marine currents and waves.

Coquina fragments are easily broken. Soft and highly porous,

coquina is found in varying tones of white. Deposits found

recently in Florida have been used as roadbed material and as a

masonry stone for homes." (Source: Grolier Multimedia

Encyclopedia). See also Wikipedia

The Standard

Guide,

St.

Augustine (1890) says that coquina quarries for

local buildings were found on St. Anastasia Island.

[ Back

]

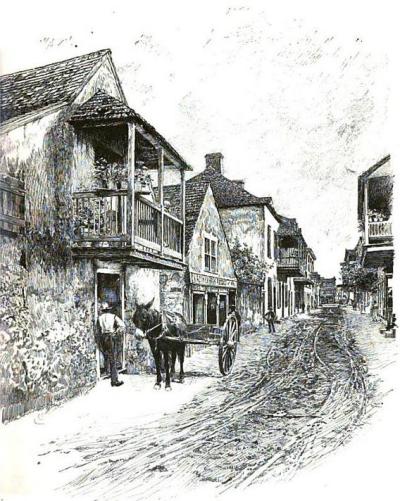

Charlotte Street. St. Augustine

Coquina house and wall on the left.

Reynolds, p. 11.

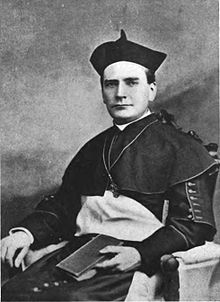

Moore was born in Ireland and immigrated to Charleston, SC when he was 14. Reading his speeches out loud in the story suggests that Jewett has given him an Irish voice, though she does not present his speech in dialect. Within the time-frame of the story, Bishop Moore would have been 55-57 years old. Jewett's narrator seems to imply that he is older, though this would be difficult to judge.

[ Back ]

Bishop John Moore

Wikipedia

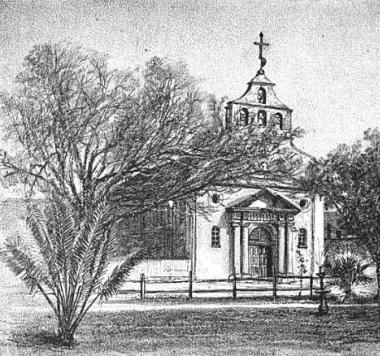

The church was burned in April 1887 and rebuilt by 1888. By the time of Jewett's second trip in 1890, the new bell tower would have been added. The drawing Reynolds provides below does not show the bell tower.

[ Back ]

Cathedral from the Plaza de la Constitucion.

Reynolds, p. 53

The Cathedral Basilica as Jewett (and Marty) probably saw it.

Wikipedia.

Gulf Stream: The Gulf Stream is a

warm ocean current originating in the Gulf of Mexico and flowing

into the North Atlantic. According to Wikipedia, Ponce

de León (1474-1521) the explorer of Florida, including the

St. Augustine area, was the first European to encounter the Gulf

Stream near Florida.

[ Back

]

Mount Desert: An Atlantic

island in Hancock County, southeastern Maine, U.S. The island

was first visited in September 1604 by the French explorer

Samuel de Champlain and was named by him for the bare-rock

summits of its mountains. A bridge connects the mainland and the

island's network of roads, bridle paths, and foot paths. The

first eastern national park in the United States, Acadia

National Park, was established on the island in 1919. (Source, Britannica

Online; Research, Barbara Martens).

[ Back

]

Boothbay Harbor: A town on the

Maine coast, northeast of Portland.

[ Back

]

bright reflections from the

schooner: This sentence is probably

incomplete. Perhaps it should read, "... factory, and the

water twinkled with bright reflections from the schooner."

[ Back ]

laws of Maine: In 1851, Maine enacted

"the Maine Law," outlawing the sale of alcoholic beverages in

the state.

[ Back ]

Monhegan: An island and a town roughly 40 miles east of Portland, Maine; there is a lighthouse on this island.

[ Back ]

Bar Harbor: A town on the east side of

the island of Mount Desert.

[ Back ]

Portland: Largest town in Maine,

on the southern coast.

[ Back ]

Moody and Sankey song-book: Probably

this is Gospel

Hymns - Consolidated (1883), by popular evangelists

Dwight Lyman Moody (1837-1899) and Ira Sankey.

[ Back ]

queer striped light-house:

This is the present lighthouse in St. Augustine, Florida, which

stands on Anastasia Island, east of the city. Designed by

Paul Pelz, it was completed in 1874. See Wikipedia.

(Research: Gabe Heller).

[ Back

]

St. Augustine Lighthouse

Probably viewed from a southerly point.

Reynolds, p. 78

Northeast Harbor: A town on the

south side of the island of Mount Desert.

[ Back

]

gray old fort:

According to Reynolds's Standard Guide the old fort, the

Castillo de San Marcos, called Fort Marion in Reynolds, was

built by the Spanish colonists, beginning in 1672, but not fully

completed in coquina limestone until about 1756. Though

golden colored when quarried, local coquina turns gray with age.

The fort remains a major feature of the city. See

Reynolds, pp. 52-67. (Research assistance: Gabe

Heller).

[ Back

]

Fort Marion / Castillo de San Marcos

From Reynolds, p. 53

[ Back ]

St. George Street: (sometimes St.

George's and George) runs south from the old gates to St.

Francis Street, near the military barracks. It remains the

principal market street of the old town, and today is a

pedestrian mall from the gates to the Plaza.

[ Back

]

St. George's St.

Reynolds, p. 10

[ Back ]

new harbor jetties: The St. Augustine.com time-line for 1887 includes this entry:

"A survey of the St. Augustine harbor was conducted between May and June. The surveyors, David DuBose Gaillard and William Murray Black, proposed the construction of jetties extending from both North Beach (Vilano Beach) and Anastasia Island spaced 1,600 feet from each other. Galliard and Black produced a map of their survey, published in 1889. Their proposals led to creation of today’s 16-foot deep channel into St. Augustine’s harbor."

[ Back ]

They tried to walk on the sea-wall: The old sea wall ran next to Bay Street (Avenida Menendez today). Today the wall has been moved outward several feet, and the space between the old and new walls filled to provide open area for strolling along the harbor. Still there are stretches of "shelly mud" next the wall when the tide is out.

[ Back ]

Sea wall of coquina, at the Plaza basin.

St. Augustine

Reynolds, p. 16.

New sea wall near the Plaza, with "shelly mud" at low tide.

Looking southward from the Bridge of the Lions.

February 2015

down at the sawmill: The

St.

Sebastian

Saw and Planing Mill and its wharf were on the St. Sebastian

River, about about a mile west of the Plaza, near where the

San Sebastian Winery stands in 2015. Just north of

this mill was the St. Augustine Saw Mill, which may also

have had a wharf. See the 1885

Birdseye

Map

of St. Augustine.

[ Back ]

out by the old gates:

Residents of St. Augustine would recognizes "the gates" as a

landmark, the remains of the old city wall, the Old Gate at

the north end of St. George St. See Reynolds, pp.

44-6.

[ Back ]

The Old Gate

Looking south down St. George Street.

Reynolds, p. 45

Spanish burying-ground:

Tolomato

Cemetery

(Old Spanish Cemetery) in St. Augustine is on Cordova St.

between Orange and Saragossa Sts, just west of the old fort.

On this site was Christian Indian village of Tolomato; it

became a Catholic burial ground in the 18th and 19th

centuries. See Wikipedia.

[ Back

]

Baya Lane: Below is a

Library of Congress photograph identified as the

intersection of Baya Lane and Charlotte Street in 1880. The

New York Times of

29 March 1895 reports that most of the buildings on Baya

Lane were burned in a large fire on 28 March.

Eventually hotels were built over the street, the most

recent being the Hilton Historic Bayfront at 32 Avenida

Menendez. (Research assistance: John Woolley and Gabe

Heller).

[ Back

]

Baya Lane and Charlotte Street 1880

[ Internet source no longer available.]

loquats: "The loquat, Eriobotrya

japonica, is a small evergreen tree of the rose

family, Rosaceae, native to warm and temperate parts

of China and Japan. It grows to 9 m (30 ft) tall and bears

large, coarsely toothed, glossy green leaves with rusty,

woolly undersides. The fragrant white flowers mature into

clusters of yellow or orange pear-like fruits with a

pleasant, slightly tart taste. Loquat fruits are juicy, with

white or orange flesh surrounding smooth, brown seeds."

(Source: Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia).

Reynolds, in his guide of 1890, notes

that the scene described here was disappearing, balconies

being removed, walls replaced with picket fence, etc. (10).

[ Back

]

palmetto: The name palmetto

refers to nearly 20 species of palms in the genus Sabal

of the family Palmae. These fan-leaved palms are

native to the southeastern United States, Bermuda, the West

Indies, and northern South America. Palmetto leaves are used

for thatching roofs, for fans, and for other plant fiber

work. (Source: Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia).

Later

in

the story, the narrator says, "Lumbering carriages clattered

along the palmetto pavement." What is meant by

palmetto pavement is not obvious. David Nolan points

out that for a time during the period of the story, St.

Augustine attempted paving streets with cross-sections of

cypress. These proved ineffective during the

relatively frequent heavy rains, when the pieces would float

out of position. Robert F. Nawrocki of the St.

Augustine Historical Society, says that palmetto trees also

were used for this purpose, the cross-sections packed with

sand to hold them in place.

See below, the note on Marsh Tackeys, for

an illustration containing examples of Florida palmetto

palms.

[ Back

]

marsh tackeys: or

tacky. The Carolina Marsh Tacky, also called the Marsh

Tacky, is a breed of horse developed in America by the

Spanish. Wikipedia

says "It is a member of the Colonial Spanish group of horse

breeds, which also include the Florida Cracker Horse and the

Banker horse of North Carolina. It is a small horse, well

adapted for use in the lowland swamps of its native South

Carolina. The Marsh Tacky developed from Spanish horses

brought to the South Carolina coast by Spanish explorers,

settlers and traders as early as the 16th century."

It seems likely that Jewett actually is

referring to the Florida Cracker Horse, about which Wikipedia

says, "The Florida Cracker Horse is a breed of horse from

Florida in the United States. It is genetically and

physically similar to many other Spanish-style horses,

especially those from the Spanish Colonial Horse group. The

Florida Cracker is a gaited breed known for its agility and

speed. The Spanish first brought horses to Florida with

their expeditions in the early 1500s; as colonial settlement

progressed, they used the horses for herding cattle. These

horses developed into the Florida Cracker type seen today,

and continued to be used by Florida cowboys (known as

"crackers") until the 1930s."

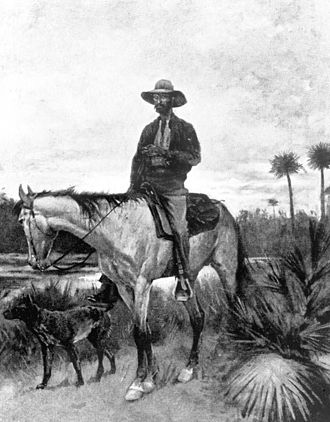

An 1895 drawing by Frederick Remington of a Florida Cracker.

From Wikipedia.

Thomas Graham, in Mr. Flagler's St. Augustine

(2014) notes that Marsh Tackeys were common in St.

Augustine, that they ran wild on Anastasia Island and that

Minorcan boys raced them on the grounds of Fort Marion

during spring festivals (pp. 19-20).

[ Back

]

Greek friezes: Greek

friezes show horses with and without cropped mains. A

cropped main on a horse used in battle might identify the

owner, or be chosen to improve speed or to make theft more

difficult. (Research: Gabe Heller).

[ Back

]

Ponce de Leon Hotel:

The Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon, (c.1460-1521) is

thought to be the European "discoverer" of Florida.

The Hotel Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine was built by Henry

Flagler in the 1888. In 1967 it became a part of

Flagler College. See Wikipedia.

[ Back

]

chinaberry-trees: A type of

mahogany native to the Himalayas, but widely planted in the

southern United States as an ornamental tree (Encyclopedia

Britannica).

[ Back

]

mocking-bird: a small bird of

the thrush family, known in the southern United States for

imitating the calls of other birds.

[ Back

]

Sisters of St. Joseph:

According

to

the history of the St. Joseph Academy, the school was

founded in 1866 by Augustin Verot, First Bishop of St.

Augustine, who invited the French Sisters of St. Joseph to

"teach literacy" to newly freed slaves after the American

Civil War. The parish school of St. Joseph, operated

by the Sisters in this story, then, would have been a

freedmen's school. From early on located on St. George

Street, adjacent to the Sisters of St. Joseph Convent, the

academy moved to 155 State Road 207 in 1980. The

convent remains at 241 Saint George Street. According

to Mary Atwood and William Weeks in Historic Homes of

Florida's First Coast (89-92), the original

convent and school were in the Father O'Reilly house at 32

Aviles St.

[ Back ]

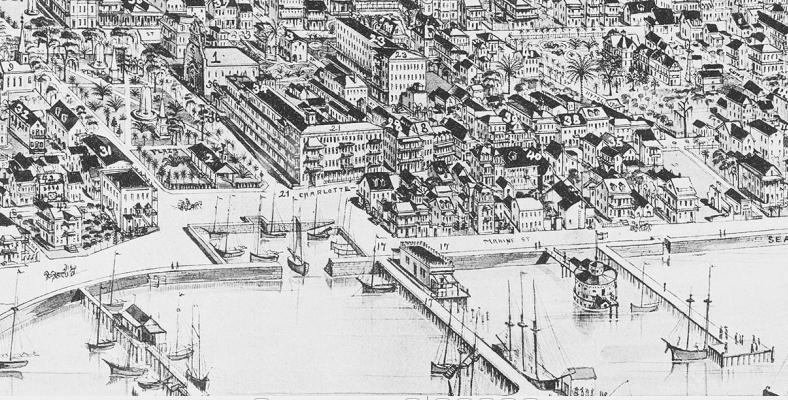

long pier: The following

detail from the 1885

Birdseye

Map

of St. Augustine (made available by St. Augustine.com)

shows several landmarks identified in the story. (North is

to the right)

The "long" pier probably is the center

pier below (at #17). This would be visible from the

plaza in front of the cathedral (#1). Jim and Marty's

house probably would stand on Bay Street (called Marine St.

on this map), near the northernmost of the three piers

visible here. That pier extends opposite the end of

Baya Lane.

By 1888, when Jewett and Annie Fields first visited St. Augustine, this view had changed significantly, for the St. Augustine Hotel (#21), on Charlotte Street and along the north side of the Plaza had burned in 1887. The fire spread to the cathedral, leaving it only a shell. The cathedral was soon restored, with an added bell tower.

[ Back ]

chaffer: to bargain.

[ Back ]

steady as a gig: in this

case, a gig is probably a long, light ship's boat with a

sail.

[ Back ]

lighthouse island: As indicated above, the

lighthouse of St. Augustine stands not far from the northern

end of Anastasia Island.

[ Back ]

the barracks:

The

United

States Military Barracks or St. Francis Barracks, according

to Reynolds (p. 70), was built by the British in 1763 on the

site of a Franciscan convent. Reynolds says "The

out-door concerts given by the military band, the

dress-parades and the guard-mount at sunset on the parade in

front of the barracks" were tourist attractions in the 1880s

and 90s. Presumably the sunset gun was part of the

guard-mount at sunset.

[ Back ]

St. Augustine station:

The train station in St. Augustine was new in 1888, built,

along with the railroad, by Henry Flagler to bring guests to

his hotels. It was located at the site where there is

currently a fire station, at the intersection Malaga and

Valencia, west of the Ponce de Leon Hotel.

[ Back ]

Martinique: Martinique, the

largest of the Windward Islands in the eastern Caribbean, is

an overseas department of France. (Source: Grolier

Multimedia Encyclopedia).

[ Back ]

horse-marines: a horse-marine

is a person out of his element, like a horseman aboard a

ship.

[ Back ]

Seguin: The Seguin Island Light

Station is on the south-central coast of Maine, off the

mouth of the Kennebec River. The current light was

completed in 1857.

[ Back

]

Contemporary photos by Terry Heller, 2015.

Main Contents & Search

A Native of Winby

Harper's Magazine Text