| Main Contents &

Search Play Days |

The story begins on a Sunday in the middle of August. Elder Grow had preached long sermons both morning and afternoon, and the people looked wilted and dusty when they came out of church. It was in the country, and only one or two families lived very near, and among the last to drive away were the Starbirds, - Jonah and his wife, and their boy and girl. The wagon creaked and rattled, and the old speckled horse hung his head and seemed to go slower than ever. It was a long, straight, sandy road, which once in a while led through a clump of pines, and nearly all the way you could see the ocean, which was about half a mile away.

There was one place that Prissy was always in a hurry to see. It was where another road turned off from this, and went down to the beach, and every Sunday when she came from church she hoped her father would go this way, by the shore. Once in a while he did so, so she always watched to see if he would not pull the left-hand rein tightest, and there was always a sigh of disappointment if the speckled horse went straight on; though, to be sure, there were reasons why the upper road was to be enjoyed. Mr. Starbird often drove through a brook which the road crossed, and there were usually some solemn white geese dabbling in the mud, which were indignant at being disturbed. Then there was a very interesting martin-house on a dingy shoemaker's shop, - a little church with its belfry and high front steps and tall windows, all complete. To-day Mr. Starbird turned the corner decidedly, saying: "I shouldn't wonder if it was a mite cooler on the beach. Any way, it can't be hotter, and it is near low water." Prissy sat up very straight on her cricket in the front of the wagon, and felt much happier, and already a great deal cooler.

"Oh, father," said she, "why don't we always go this way? It would be so much nicer going to meeting."

"Now, Prissy," said Mrs. Starbird, "I'm afraid you don't set much store by your preaching privileges;" and then they all laughed, but Prissy did not quite understand why.

"Well," said her father, "it is always three quarters of a mile further, and sometimes it happens to he high tide, and I don't like jolting over the stones; besides, I see enough of the water week-days, and Sunday I like to go through the woods."

It was cooler on the shore, and they drove into the water until the waves nearly came into the wagon, and Prissy shouted with delight. When they drove up on the dry sand again, she saw a very large sea-egg, and Sam jumped down to get it for her.

"Wouldn't it be fun," said she, "if I could tame a big fish, and make him bring me lovely things out of the sea?"

"Yes," said Sam, "or you might make friends with a mermaid."

"Oh, dear!" said Prissy, with a sigh, "I wish I could see one. You know so many ships get wrecked every year, and there must be millions of nice things down at the bottom of the sea, all spoiling in the salt water. I don't see why the waves can't just as well bring better things in shore than little broken shells, and old, good-for-nothing jelly-fishes, and wizzled-up sea-weed, and fish-bones, and chips. I think the sea is stingy!"

"I thought you were the girl who loved the sea better than 'most anything," said her mother. "I guess you feel cross, and this afternoon's sermon was long. I'm sure the sea gives us a great deal. Where should we get any money, if your father couldn't go fishing or take people sailing?"

"Oh, I do love the sea," said Prissy; "I was only wishing. I don't see, if there is a doll in the sea, - a drowned doll, you know, with nobody to play with it, - why I can't have it."

Soon they were at the end of the beach, by the hotel, and then they were not long in getting home.

Just as they were driving into the yard a little breeze began to come in from the east, and Mr. Starbird pointed to a low bank of clouds out on the horizon, and said there would be a storm before morning, or he knew nothing about weather.

"It is a little bit cooler," said his wife, "but my! I am heated through and through."

Prissy put on her old dress, and after supper she and Sam went out in the dory with their father, to look after the moorings of the sail-boat, and then they all went to bed early. And sure enough, next morning there was a storm.

It was not merely a rainy day; the wind was more like winter than summer. The waves seemed to be trying to push the pebbles up on shore, out of their way, but it was no use, for they would rattle back again as fast as they could every time. The boats at the moorings were rocking up and down on the waves, and you could hear the roaring of the great breakers that were dashing against the cliffs and making the beach beyond white with foam.

There was not much one could do in the house, and there were no girls living near whom Prissy could go to play with.

The rainy day went very slowly. For a while Prissy watched the sand-pipers flying about in the rain, and her father and Sam, who were busy mending a trawl. Finally she picked over some beans for her mother. Sam and his father went down to the fish-houses, and after dinner Prissy fell asleep, and that took most of the afternoon. She couldn't sew, for she had hurt her thimble-finger the week before, and it was not quite well yet. Just before five her father came in and said it was clearing away. "I am going out to oil the cart-wheels and tie up the harness good and strong," said he, "for there will be a master pile of sea-weed on the beach to-morrow morning, and I don't believe I have quite enough yet."

"Oh!" said Prissy, dancing up and down, "won't you let me go with you, father? You know I didn't go last time or time before, and I'll promise not to tease you to come home before you are ready. I'll work just as hard as Sam does. Oh, please do, father!"

"I didn't know it was such a good thing to go after kelp," said Mr. Starbird, laughing. "Yes, you may go, only you will have to get up before light. Put on your worst clothes, because I may want to send you out swimming after the kelp, if there doesn't seem to be much ashore." And the good-natured fisherman pulled his little girl's ears. "Like to go with father, don't you? I'm afraid you aren't going to turn out much of a housekeeper."

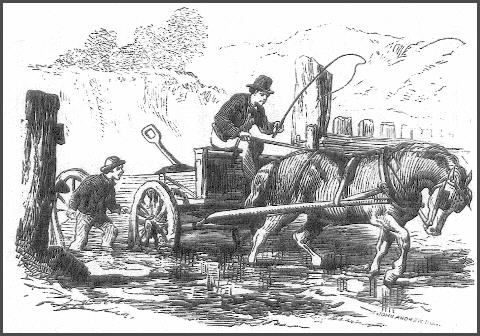

The next morning, just after daybreak, they rode away in the cart, - Mr. Starbird and Prissy on the seat, and Sam standing up behind, - drawn by the sleepy, weather-beaten little horse. It had stopped raining, and the wind did not blow much; the waves were still noisy and the sun was coming up clear and bright. They saw some of their neighbors on the way to the sands, and others were already there when the Starbird cart arrived. For the next two hours Prissy was busy as a beaver, picking out the very largest leaves of the broad, brown, curly-edged kelp. Sometimes she would stop for a minute to look at the shells to which the roots often clung, and some of them were very pretty with their pearl lining and spots of purple and white where the outer brown shell had worn away. Prissy carried ever so many of these high up on the sand to keep, and often came across a sea-egg, or a striped pebble or a very smooth white one, or a crab's back reddened in the sun, and sometimes there was a bit of bright crimson sea-weed floating in the water or left on the sand. Besides these, there seemed to be a remarkable harvest of horse-shoe crabs, for at last she had so many that she took a short vacation so as to give herself time to arrange them in a graceful circle around the rest of her possessions, by sticking their sharp tails into the sand. It was great fun to run into the water a little way after a long strip of weed that was going out with the wave, and once, as she came splashing back, trailing the prize behind her, one of the neighbors shouted good-naturedly: "Got a fine, lively mate this voyage, haven't ye, Starbird?"

Nearly all the men in the neighborhood were there with their carts by five o'clock, and there was a great deal of business going on, for the tide had turned at four, and when it was high there could be no more work done. The piles of sea-weed upon the rocks grew higher and higher. In the middle of the day the men would begin loading the carts again and carrying them home to the farms. You could see the great brown loads go creaking home with the salt water still shining on the kelp that trailed over the sides of the carts. You must ask papa to tell you why the sea-weed is good for the land, or perhaps you already know?

But now comes the most exciting part of the story. What do you think happened to Prissy? Not that she saw a mermaid and was invited to come under the sea and choose out a present for herself, but she caught sight of a bit of something bright blue in a snarl of sea-weed, and when she took it out of the water, what should it be but a doll's dress!

And the doll's dress had a doll in it! Just as she reached it, the waved rolled it over and showed her its beautiful face. Prissy was splashed up to the very ears, but that would soon dry in the sun, and oh, joy of joys, such a dear doll as it was. The blue she had seen was its real silk dress, and Prissy had only made believe her dolls wore silk dresses before. And, as she pulled away the sea-weed that was all tangled around it, she saw it had a prettier china head than any she had ever seen, lovely blue eyes, and pink cheeks, and fair yellow hair. Prissy's Sunday wish had certainly come true. What should she wish for next?

But she could not waste much time thinking of that, for she found that the silk dress was made to take off, and there were little buttons and button-holes, and such pretty white underclothes, and a pair of striped stockings and cunning blue boots - but those were only painted on. Never mind! the salt water would have ruined real ones. There was a string of fine blue and gilt beads around her neck, and in the pocket of the dress - for there was a real pocket - Prissy found such a pretty little handkerchief! Was this truly the same world, and how had she ever lived alone without this dolly? Some kind fish must have wrapped the little lady in the soft weeds so she could not be broken. Had a thoughtful mermaid dressed her? Perhaps one had been a little way out, hiding under a big wave on Sunday, and had heard what the Starbirds said as they drove home from church. Prissy was just as certain the doll was sent to her as if she had come in a big shell with "Miss Priscilla Starbird" on the outside, and two big lobsters for express men.

How surprised Mr. Starbird was when Prissy came running down the beach with the doll in her hand. Sam was hot and tired, and didn't seem to think it was good for much. "I wonder whose it is?" said he. "I s'pose somebody lost it."

"Oh, Sam!" said Prissy, "she is my own dear dolly. I never thought she was not mine. Can't I keep her? Oh, father!" - and the poor little soul sat down and cried. It was such a disappointment.

"There, don't feel so bad, Prissy," said Mr. Starbird, consolingly, "I wouldn't take on so, dear. Father'll get you a first-rate doll the next time he goes to Portsmouth. I suppose this one belongs to some child at the hotel, and we will stop and see as we go home." And Prissy laid the doll on the sand beside her, and cried more and more, while Sam, who was particularly cross to-day, said, "Such a piece of work about an old wet doll!"

"Oh," thought Prissy, "I kept thinking she was my truly own doll, and I was going to make new dresses, and I should have kept all her clothes in my best little bit of a trunk that grandma gave me. I don't believe any Portsmouth doll will be half so nice, and I shouldn't have been lonesome any more."

Wasn't it very hard?

But Prissy was an honest little girl,

and when her father told her he was ready to go, she was ready

too, and had the horse-shoe crabs transplanted from the sand

into a strip of kelp in which she had made little holes with a

piece of sharp shell, and the best shells and stones were piled

up in her lap. She had made up her mind she could not have the

doll, and she looked very sad and disappointed. It was nearly a

mile to the hotel, and it seemed longer, for the speckled

horse's load was very heavy. Prissy hugged the water dolly very

close, and kissed her a great many times before they stopped at

the hotel piazza.

Mr. Starbird asked a young man if he

knew of any child who had lost her doll, but he shook his head.

This was encouraging, for he looked like a young man who knew a

great deal. Then a boy standing near said, "Why, that's Nelly

Hunt's doll. I'll go and find her."

Mr. Starbird went round to see the landlord, to arrange about carrying out a fishing-party that afternoon, and Prissy felt very shy and lonesome waiting there alone on the load of sea-weed. She gave the dolly a parting hug, and the tears began to come into her eyes again.

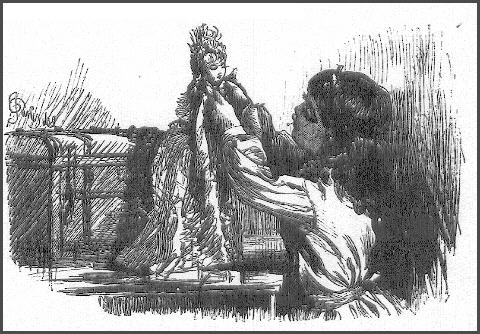

In a few minutes a tall, kind-looking lady came down-stairs and out on the piazza, and a little girl followed her. Prissy held out the doll without a word. It would have been so nice to have her to sleep with that night.

"Where in the world did you find her, my dear?" said the lady in the sweetest way; "you are a good little girl to have brought her home. What have you been crying about? Did you wish she was yours?" And she laid her soft white hand on Prissy's little sandy, sunburnt one.

"Yes'm," said Prissy; "I did think she was going to be my doll, and then father said somebody must have lost her. I shouldn't like to be the other girl, and be afraid she was drowned."

This was a long speech from our friend, for she usually was afraid of strangers, and particularly the hotel people. The lady smiled, and stooped to whisper to the little girl, who in a minute said, "Yes, indeed, mamma," aloud.

"Nelly says she will give you the dolly," said the lady. "We are sorry her clothes are spoiled, but some day, if you will come over, I will give you some pieces to make a new dress of. It will have to be either black or white, for I have nothing else here, but I can find you some bright ribbons. Nelly left her out on the rocks, and the tide washed her away. I hope you will not be such a careless mamma as that."

"Haven't you any dolls of your own?" said Nelly; "I've six others. This one is Miss Bessie."

"No," said Prissy, who began to feel very brave and happy. "I had one the first of the summer. It was only a rag baby, and she was spoiled in the rain. Oh, I think you're real good!" And her eyes grew brighter and brighter.

"Dear little soul," said Mrs. Hunt, as she went in, after Mr. Starbird had come back, and they had gone away, "I wish you had seen her hug that doll as she turned the corner. I think I never saw a child seem happier. It had been so hard for her to think she must give it up. I must find out where she lives."

You will know that Prissy went home in a most joyful state of mind. In the afternoon, directly after dinner, she went down to the play-house, carrying the shells and crabs, and she and the new dolly set up housekeeping. The play-house was in a corner where there was a high rock at the end of a fence. There were ledges in the rock that made some shelves, and Sam had roofed it over with a few long boards, put from the top of the rock to the fence, so it was very cozy. There were rows of different kinds of shells and crab-backs, marvelous sea-eggs, and big barnacles by the dozen. Sam had rolled in a piece of drift-wood, that had been part of the knee of a ship, and who could want a better sofa? There was a bit of looking-glass fastened to the fence by tacks, and there had been some pictures pinned up that Prissy had cut out of a paper, but these were nearly worn out by the rain. A bottle, with a big, jolly marigold in it, stood on a point of the rock that she called her mantelpiece. Besides these treasures, she had a china mug, painted red, with "Friendship's Offering" on it in gilt letters. The first thing she did was to go down to the shore, where she was busy for some time washing the dolly's clothes, which were very much spotted and crumpled, and full of sand and bits of sea-weed. The silk dress could only be brushed, her mother told her, and would not be quite clean again; but after all it was grand.

Prissy's "wash" was soon hung out on a

bit of fishline, stretched near the play-house, and the doll,

who had been taking a nap during this time, was waked up by her

new mother. The sun shone bravely in at the door, and all the

shells glistened. Prissy counted the sails out at sea, and

noticed how near the light-house looked that day. "When I go out

there again, you may go, too," said she to the doll; "you won't

be a bit sea-sick, dear."

The water dolly looked happy, as if she

felt quite at home. Nelly Hunt came over next morning with a box

of "Miss Bessie's" clothes and a paper of candy, and when she

saw the play-house she liked it so much that she stayed all the

rest of the morning, and came to see Prissy ever so many times

that summer before she went away.

Notes

"The Water Dolly" first appeared in St.

Nicholas Magazine (1:52-56) in December 1873 where it was

illustrated. The artist has not been identified. Information on

this would be welcome; please contact the site manager.

This text is from Play Days, where the story was

collected.

[ Back ]

martin-house: In North America, the

purple martin, a bird of the swallow family, prefers to build

its nest on buildings. Often a man-made martin house would

contain several separate compartments for multiple nests.

[ Back ]

her cricket: a wooden footstool.

[ Back ]

sea-egg: a sea urchin.

[ Back ]

wizzled-up sea-weed: "Wizzled"

appears to be made up or a localism. Context suggests it means

whithered or dried up, as in wizened.

[ Back ]

sand-pipers: a bird of the snipe

family, found along the seacoast

[ Back ]

trawl: According to the ARTFL

Project on-line 1913 Webster's Dictionary, a trawl may be a

fishing line, often extending a mile or more, having many short

lines bearing hooks attached to it. It is used for catching cod,

halibut, etc.; or large bag net attached to a beam with iron

frames at its ends, and dragged at the bottom of the sea, --

used in fishing, and in gathering forms of marine life from the

sea bottom.

[ Back ]

horse-shoe crabs: "Horseshoe

crabs, also called king crabs, are large marine animals with

horseshoe-curved shells. Actually, they are not crabs but are

related to spiders. Horseshoe crabs constitute the order or

subclass Xiphosura of the class Merostomata,

phylum Arthropoda." Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia.

[ Back ]

Portsmouth: a seaport in New Hampshire.

[ Back ]

rag baby: a home-made doll, usually

made of cloth and stuffed with rags.

[ Back ]

knee of a ship: A naturally or

artificially bent piece of wood, used in various ways in

shipbuilding, for example, to connect beams and timbers of a

wooden ship.

[ Back ]

"Friendship's Offering": A popular annual Christmas gift book of the early 19th Century, for example: Friendship's Offering and Winter's Wreath. London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1836 and Friendship's Offering: A Christmas, New Year, and Birthday Present, for MDCCCLII.. Philadelphia: E. H. Butler & Co. 1852.

"Friendship's Offering" (1832) by Thomas Haynes Bailey appeared in the prefaces to some of these annual collections:

To whom shall FRIENDSHIP'S OFFERING

Be sent, if not to Thee?

Whose smiles of friendship have so long

Been treasured up for Me?

For thou has shared my joy and grief:

The one thou mad'st more gay;

And from the other thou did'st steal

All bitterness away.

LOVE'S tribute long ago I gave

And thine it still shall be;

And Friendship's offering I'll send

To none, if not to Thee.

And what is Friendship's offering?

What tribute will she send?

Are costly gems, and gold, the gifts

That friend bestows on friend?

The ruby ring? the sparkling chain?

If such alone can please,

Oh they must come from other friends,

For I have none of these!

But no, it is a simpler gift

That Friendship will prefer,

A gift whose greatest worth consists

In being sent by Her:

It is a volume in whose leaves

No sentiment is traced

That Virtue, in her gravest mood,

Would wish to see effaced:

The muses fill all leaves but one,

And ere the book I send,

On that leaf I will trace the name

Of my own dearest Friend.

Love's tribute long ago I gave,

And thine it shall still be,

And FRIENDSHIP'S OFFERING I'll send

To None--if not to Thee.

(from

http://www.pgmill.com/english/FOindex.htm)

(Research: Gabe Heller)

[ Back ]

Edited and annotated by Terry Heller, with assistance by Chris Butler, Coe College

| Main Contents &

Search Play Days |